Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Andrusz - From Wall To Mall

Uploaded by

Besmira DycaOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Andrusz - From Wall To Mall

Uploaded by

Besmira DycaCopyright:

Available Formats

From Wall to Mall

Gregory Andrusz Emeritus Professor of Sociology School of Health and Social Science Middlesex University Archway Campus Highgate Hill London N19 5LW (44 207) 607 1292 e-mail: G.Andrusz@mdx.ac.uk; gandrusz@blueyonder.co.uk

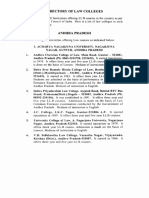

ABSTRACT This paper focuses on four issues in the post-socialist cities of central and eastern Europe and the countries of the FSU. The principal empirical sources are Moscow and St. Petersburg. It firstly suggests that social polarisation in these cities manifests itself in the emergence of housing classes (pace Rex). The second issue revolves around the development of a new type of economy within the service sector, and the rise of the individualised worker who creates a demand for work space, an attractive social environment and accommodation. The third issue is the rise of the Mall as the epitome of consumerism. The fourth theme, which envelopes the previous topics, raises the question of the significance to be attached to the symbolism inherent in monuments and buildings in projecting legitimising ideologies and myths for social polarisation and mall-making. An unstated hypothesis is that these processes may be witnessed in all post-socialist capital cities and, to a lesser extent, in smaller regional centres.

Conference: Winds of Societal Change: Remaking Post-Communist Cities University of Illinois, June 18-19, 2004

Introduction The forms and functions that the post-socialist cities are assuming are determined by their socialist and pre-socialist legacies and by their position and status within the region. It is doubtful that we can talk of a generic socialism, beyond a general characterisation that each country passed legislation abolishing the private ownership of property1, thereby concentrating most economic resources in the hands of the state, and political power in the hands of a vanguard party. Thus the term post-socialist describes urban areas in societies which, until the breaching of the Berlin Wall in 1989, had been known as socialist. If it is accepted that these were real existing socialist societies (Bahro, 1977) then their cities were by definition socialist cities - the position adopted in the Soviet Union in 1931. Arguably an a fortiori case exists for believing that Russia, which had the longest period in which to experiment and put its ideological principles into practice, displayed in its urban form the characteristics of a socialist city. Despite dissenters, the consensus is that the socialist city was qualitatively different from the city in capitalist society (French, 1979; Smith, 1996; Szelenyi, 1996). At the 25th Congress of the CPSU in 1975, Mr. Brezhnev announced that Soviet society, having reached the stage of mature socialism, less socially developed institutional forms were to be abandoned: collective farms, representing a lower form of (co-operative) socialism would be replaced by state farms. Just over a decade later, Mr. Gorbachev, describing the previous decade as one of stagnation, began a radical reversal of this policy. The vision of the new leader and his advisors was that of a revival of precisely those older forms that Brezhnev had sought to abolish, in particular, co-operatives. At the same time they initiated a programme of perestroika, which paralleled the restructuring that Mrs. Thatcher had embarked upon in the UK, as she set about removing restrictions on capital flows, and embraced the information society (Castells, 1989, 1996)2. But reform of the system through the pursuit of a third way was unacceptable to messianic missionaries of capitalism; for over twenty years Western businessmen and multinational companies had been breaching the Wall and beginning to fulfil Marx's prediction in regard to the barbarian nations of the 'east' (Marx, 1848/1962: 38); by 1989 the beleaguered wall of socialism was visibly crumbling until finally in 1990, with trumpets blaring, the Wall around Berlin came tumbling down. The removal of this important barrier to globalisation is associated with a weakening of the ability of national governments to regulate capital flows and thus pursue an independent economic and social policy. Just as Wroclaw (Breslau) was one of the (final) bastions of the Third Reich in 1945 (Davies & Moorehouse, 2002: 18 et pass), so the Berlin Wall was the ultimate Festung of real-existing socialism in Europe (e.g. Ray, 1996)3. In the eyes of the regime, it existed to defend the system from ideological pollution and insidious invasion from the capitalist West; from the other side, the Wall represented a grotesque symbol of state repression. The systematic study of the type of city that grew up behind the protective socialist Wall should be contextualised by examining it against the vision held by socialist city planners4 and

This is a fraught question. See, for example, Marcuse 1996 pp.119-191 Castells has used the term informational capitalism to define a period and type of capitalism where the exchange value of information has come to challenge that of commodity production. 3 It shares this status with the Parliament Building in Moscow (the White House) besieged by Yeltsin in October 1993. 4 Before criticising the actors in the past, it is necessary to see events as they were seen at the time (Davies, 2003: xv-xxxix; Evans, 1997).

2 1

Andrusz: From Wall to Mall

Conference: Winds of Societal Change: Remaking Post-Communist Cities University of Illinois, June 18-19, 2004

by their counterparts in West European social democracies (Hamm, B. (Ed), 1984; Hamm, B. & Jalowiecki, B. (Eds), 1984). Architects, civil engineers and planners formulated their ideas in the light of the technologies available to them; while the ideological and political context and institutional capabilities conditioned what could be done in practice (Kopp, 1970; Bliznakov, 1990; 1993). Metropolitan cities5 and regional capitals are the distillery of societys contradictions and conflicts and contain in hypertrophied form what is found to a much lesser extent in all other cities. They remain the home of the cultural avant-garde, of the social and political misfit and the new economy (see below) and they provide the space within which the Mall is being fashioned and tested. It is here that the boundaries of post-modernism are tested in the citys external form and in the social content of its public and private spaces. This paper focuses on changes in Moscow and St. Petersburg; but it is contended that key elements of life behind the Wall and of the journey towards creating far more class polarised post-socialist cities, and consumer-oriented societies, represented by the Mall, are common to all major cities in the region. Behind the Wall: the Socialist City The socialist city in symbolic form and housing content The legacy of the socialist city is not confined to a few experimental buildings erected in the1920s, nor to the few neo-classical, doric-columned residential and non-residential buildings and railway stations built during the Stalin era; nor to the large squares with their statues of political, literary and military heroes. Nor, finally, can that legacy be reduced to those monotonous multi-storey blocks of flats, the blueprint which the leadership of all socialist societies drew upon after 1949. This aspect of the legacy was, despite its weaknesses, at least constructive: these changes to the environment were intended to improve the material standard of living and to fundamentally alter attitudes and social relationships. Another part of the legacy was avowedly destructive: Soviet leaders, especially, but not only, Stalin and Khrushchev, and many local activists did much to remove all vestiges of the tsarist past, particularly through the demolition of churches (e.g. Ruble, 1995). This truly iconoclastic act offers an entry point into exploring both the socialist and post-socialist city and the interweaving of the material with the symbolic. One example captures the period and the policy - the building of the Cathedral of Christ the Saviour in Moscow, originally conceived as commemorating the defeat of Napoleon in 18126. The symbolism of the choice of date and name are matched by the establishment of a Monuments Demolition Committee by the Union of Art Activists7 in February 1917 although nothing was done until 1931, when the Cathedral was dynamited (Chihireva, 2002). A swimming pool built on the site after the war was demolished in 1994 and an exact replica of the original Cathedral was finally completed in 2000.

The metropolis is understood as a mother city, a substantial conurbation, which exceeds the scale of the traditional city. Leach, 2002, p.1 6 Work eventually began on the final site in 1839 and continued until 1881, when its consecration had to be postponed because of the assassination of Alexander II in that year. 7 For Soviet Marxism the orthodox church was as much an ideological enemy as capitalism and so the socialist state robbed them of their riches and, like trophies of war, destroyed them or transformed them into museums or used them as warehouses. In 1932, the Soviet government turned the Cathedral of the Virgin of Kazan in Saint Petersburg, named after the famous icon of the Virgin and in honour of Ivan the Terribles capture of Kazan, into a Museum of the History of Religion and Atheism. Andrusz: From Wall to Mall 3

5

Conference: Winds of Societal Change: Remaking Post-Communist Cities University of Illinois, June 18-19, 2004

Changing architectural styles, the functions of a towns most impressive buildings and the manner in which public spaces are used serve as sound barometers of the place of historical events and subjects in the mind of politicians, the public and the media. The memorial and monument, which became popular at the turn of the 20th century, spread like a post First World War epidemic, especially in the newly created east and central European states (Jezernik, 1998). This process reached its apogee in the socialist city - in the USSR after 1917, and elsewhere in Eastern Europe after 1948. For instance in one Slovakian town, the Masaryk Square became the Slovak National Uprising Square, while nearby a baroque Marian column was relocated to a less visible place. More generally, obelisks, which were erected to commemorate the Red Army and marble memorials to partisan leaders, who had played a part in the liberation of the country from fascism (and capitalism), embellished (and are now seen to blemish) parks, squares and streets of towns and villages. On the other hand, the communist regimes did not totally efface the built environment that they had come to inhabit: huge resources were expended on the meticulous restoration of Warsaws old town (stary miasto) and opera house and on the palaces at Peterhof and Tsarskoe Selo (Pushkin) outside St. Petersburg, which had been almost completely destroyed during the siege. In the main, however, the dilemma of whether to restore or modernise was resolved in favour of designing and building an environment suited to the new socialist person. The shift which had taken place in the 1960s in Western urban planning theory from clearance and new build on greenfield sites to renewal and modernisation of existing housing and whole neighbourhoods, began to percolate into debates in socialist countries, which by the mid-1970s, according to the Brezhnev doctrine, had entered the phase of mature socialism, when a shift was supposedly taking place from quantity (producing as much as possible) to quality. Little, however, was done: the emphasis remained on quantity (numbers of new dwelling units), and renewal was ignored. The Post-Socialist City Introduction In 1989, socialist cities slipped across a boundary into a new, ideologically denominated zone to become post-socialist cities. The transformation of societies and cities from being socialist to post-socialist is not a unilinear process, neither is the sequencing and the time-scale (Harloe, 1996), which depend on, among other things, systems of local governance, legal and institutional frameworks, the manner in which privatised public assets were distributed and the skills, networks, the orientations (including time-perspective) of the new capitalists and the perceptions of Western investors and governments (Hamilton, 1999). An almost universally shared feature has been a shift from a vision of the future within a collectivist ethos to one that, as in other European cities, fabricates convenience histories8 to fill spaces with symbolic meanings (Hobsbawm, 1983; Samuel, 1996). In many post-socialist cities, people who forty years ago were heroes of socialism, to whom statues and memorials were erected, have been, if not destroyed, decapitated or mutilated, then banished from public view, in some instances to museums so that they may be reminders of the images of dictators and criminals. These acts highlight the transience not just of heroes, but also of the myths about the present inhabitants

Many traditions, thought of as dating from some point in antiquity and sanctioned by long usage over the centuries, are not infrequently of comparatively recent invention. Andrusz: From Wall to Mall 4

8

Conference: Winds of Societal Change: Remaking Post-Communist Cities University of Illinois, June 18-19, 2004

past and who they wish or perceive themselves to be. The erection and removal of monuments and buildings totems to the regime - are potent symbolic acts, which create and sustain myths about people and events and then denigrate and depose them. In the post-socialist city new buildings themselves are monuments, but less to people or events than to the new-found ideology (liberal democracy) and the power of money (the market), both of which tend to be expressed through the dominant use of glass in architecture, representing transparency in the exercise of political power and the availability of everything to everyone. This contrasts with the socialist city where often coarse granite blocks, which characterised government and other public buildings, served to conceal political decision making and nurtured under-the-counter selling of products in shops. As far as the social is concerned, post-socialist leaders have been rushing to undo the devastation of their predecessors by rebuilding churches - totems for non-believers as well as believers, providing a focal point, as Durkheim observed, for people to reaffirm their adherence to a set of values and historical reference points (religious and other public holidays and festivals) and group identities. The post-socialist city: a class discourse through a housing window There are certain complexes of urban and housing phenomena suburbanisation, gentrification, homelessness and changing policies towards subsidised social housing which occur in all advanced urban-industrial societies based on a market system. We are now witnessing within the region how a small, but more affluent, middle class are buying cars and speeding off to the green-field suburbs. At the same time, socialist and pre-socialist accommodation in the inner city is being modernised and blocks are being gentrified, accompanied by a boom in cafes and restaurants to cater for the new elites, whose recreation is no longer spent in a Party or trade union sanatorium in a pre-socialist spa (such as Kislovodsk or Marienbad) but in the urban fitness club. These processes coincide with a loss of manufacturing jobs located in cities, whose space is taken over by companies in the service sector - high tech, finance, advertising and media which employs fewer people. The low-income jobs being created to service this sector are usually given to migrants from the countryside9 and immigrants. The outcome of these processes has been a rise in unemployment and in the incidence of homeless persons and households and a growth in the informal economy. Real poverty and perceptions, especially by a section of the younger generation of relative deprivation, have helped to underpin the growth in the tentacular reach of drug dealers and organised crime. The root cause of this rapid social polarisation was the law passed in 1991, allowing state-owned housing to be privatised10. The haemorrhaging of public funds from the state budget to sustain the housing system might compel the government to find a way to terminate one of the most bizarre aspects of housing policy, but not until the expiry of the current strategy document (Strategii zhilishchnoi politiki i razvitiya zhilishchnogo-kommunalnogo khozyaistva na 2001-2005). Currently, the 1991 law on housing privatisation allows the recipients of newly built housing, financed out of

This also applied to new arrivals in the socialist city from the countryside, who worked as sales assistants and in other poorly paid jobs in the non-productive sector of the economy. 10 Zakon RF, 4 July 1991, No. 1541-1, O privatizatsii zhilishchnogo fonda v Rossiiskoi Federatsii. Article 5 of the Law did not extend the right to privatise to households living in hostels, housing in closed military towns and other types of service accommodation. The law was signed by Boris Yeltsin, then the Chairman of the Supreme Soviet of the RSFSR. At that date, 67 per cent of the total housing stock was state owned; in towns the figure was 79 per cent, rising to 90 per cent in the largest cities. Andrusz: From Wall to Mall 5

9

Conference: Winds of Societal Change: Remaking Post-Communist Cities University of Illinois, June 18-19, 2004

public funds, to privatise the property and sell it as soon as they have successfully claimed and been granted private title11. Rescinding these provisions in the law would not only deprive those still on housing waiting lists from receiving this generous gift from the public purse, but would also bring to an end the second, redistributive stage in Russian housing policy12. A majority of households in this situation belong to one of the multitude of social categories, accounting for over 70 per cent of the population, entitled to social benefits in the form of monetary or in-kind payments (Ovcharova, 2002: 6, 13), and eligible for housing allowances13. For one section of the population, apart from legislation permitting private ownership of real estate and land, most of the vast body of statutory law governing housing and town planning is an irrelevance14 People who are superlatively rich buy their properties outright and tend to live segregated from others in high security gated communities, outside the city or in a renovated house or flat in the city itself. Their houses, sumptuous by any standard, particularly in Moscow are typically in one of the capitals suburbs amongst firs within a walled compound as part of an usadba (country estate) (Kishkovsky, 2003). The aristocratic display of wealth, revealed in countless Russian15 and English language magazines16 as has the way in which their wealth was accumulated (Goldman, 2003), is already legendary. Many of these developments meet the desire by the nouveaux riches to emulate the pre-revolutionary aristocracy17. The principal residence, including furniture and land, typically costs over US$3 million, and can include a guesthouse and separate quarters for servants and bodyguards. Guests at one estate leave their Mercedes-Benzes at the gate and ride to the house by horse and carriage (Kishkovsky, 2003)18. But not all those who constitute this super-wealthy class are rushing to re-brand themselves as the landed gentry. As Moscow transforms itself into a modern metropolis, with luxury hotels, shopping malls and office complexes, other members of this super rich bourgeoisie and rentier class prefer to live in gentrified houses in the historic core and adjacent districts. They seek out buildings with ornate, sometimes neo-classical facades and high ceilings and city centre locations erected before 1917 and built for members of the Soviet lites in the

In 1998-1999, over 28,000 flats became the private property of their tenants. See: Basargin et al. (2000) The first one was in 1917-1919, when accommodation belonging to landlords and owner occupiers was expropriated. (See below). In contrast, the 1991 Law has redistributed property in the opposite direction. 13 Zakon Rossiiskoi Federatsii, Ob osnovakh federalnoizhilishchnoi politiki, 22 December 1992, No. 4218-1 14 In May 2004, it was estimated that the 36 richest individuals in Russia owned US$110 billion, equivalent to 24% of GDP. 15 For instance, see the Russian glossy magazine, : for self-made men only, published in Nizhnii Novgorod (the third largest city in Russia) which, in the April 2002 issue, following a full page advertisement in English (the real french kiss: Hennessy carries an article . 16 The Russian passion for all things luxurious is driving the worlds big fashion labels and single-handedly rescuing the luxury-goods industry from its economic mire they are now one of the most influential consumer groups in the worldIn 1994 Versace opened in Moscow and Russia now accounts for10% of the total sales of the labelCeline and Louis Vuitton run special customer evenings just for their London-based Russian clients. No other nationality is being targeted in this way, From Russia with Cash, The Sunday Times, (Style Supplement) (UK), 18 April, 2004 p.18. 17 They are following in the footsteps of the President whose official presidential residence in St. Petersburg in the 18th-century Konstantinovsky Palace cost nearly US$200 million to restore. 18 Another estate has its own stables and church; the architect of another created a coat of arms to mount on the facade of one family's small estate. A magazine industry has emerged to cater for the consumers and admirers of this ostentatious style of life. The promotional literature for a condominium complex, which will have a formal garden based on Peter the Great's Peterhof, and Bach piped into the parking garage, refers to the complex as a "XXI century aristocratic estate" whose residents, paying up toUS$1 million for a flat (90% of which have been sold), can justly call themselves the new aristocrats.

12 11

Andrusz: From Wall to Mall

Conference: Winds of Societal Change: Remaking Post-Communist Cities University of Illinois, June 18-19, 2004

1930s and in the decade after 1945. Although in theory, any new construction project within the city's historical core is rigorously vetted to ensure that it complies with zoning laws and environmental-impact regulations (Gradostroitelnyi kodeks, 2003)19, in practice many old houses, which merit restoring, are demolished to provide for car parking, office space and new or gentrified accommodation (OFlynn, 2004; 9; Scott, 2004; Gritsai, 1997)20. The outcome of protests by residents follows a familiar pattern: Initially, a well-presented petition succeeds in persuading the local authorities to adhere to their own zoning and development plans. But, as real estate prices, especially in the capital, continue to climb, developers, working in close collaboration with local officials, after a brief delay (out of respect for planning regulations local opposition) achieve their objective which is to modernise and refurbish a single building or block for residential or other use and to displace the original population (Bater et al. 1998). This new bourgeoisie is trailed and admired by a much poorer, aspirant middle class, whose members strive to emulate the exceedingly rich by taking part in the game of homeimprovements, looking at the advertisements for Gaetano (for their private spaces) just as they once looked at monuments to Lenin and Gagarin (in the previously more important public space). They comprise an audience for a Russian version of the successful British television programme, Changing Rooms. Each episode of Kvartirnyi Vopros invites guest designers and skilled craftsmen to convert an average room in a Moscow block of flats into something far more stylish, using both Russian and West European furnishings. Moscows two Ikea stores21 are the flagships of the booming D-I-Y vogue. As with the very rich, who want to emulate the tsarist aristocracy, an unknown proportion of this more humble class revels in nostalgia, for example, by reinstating or improving the position of the icon in its traditional corner for religious, cultural or decorative reasons. But the past is not all tsarist; a retro-socialist chic is carving a space in the post-modern, capital city. This home-ownership seeking group contains an emerging small landlord class, composed of both foreigners and natives, interested in restoring and then renting out their properties in selective, gentrified areas. A converted two-bedroom loft space in a 19th-century building in St. Petersburgs historic centre, with exposed wooden beams and brickwork, resembles the SoHo loft district rather than Imperial Russia (Varoli, 2003) and has a market value of c.US$150,000. It is one of three attics which the foreign interior designer has acquired and renovated and now rents out. While the right to reclaim such derelict spaces conforms to the governments policy of increasing the housing stock, this example of gentrification generates envy and litigation over title to property, part of which is communally owned. It is towards this

19

The Town Planning Code was ratified by the State Duma on 8 April 1998 and incorporated into Federal Law on 10 January 2003, no. 15-FZ. 20 In the case of Moscow, Yelena Baturina, the wife of the Mayor, Yurii Luzhkov, is director of a company, Inteko, which among other things controls a house building combine (DSK-3), a major producer of the cement panels that continue to be widely used in housing construction throughout the country. In February 2004 her company purchased a 93.4 per cent stake in Oskolcement for US$90ml thereby consolidating further her financial interest in real estate development. Cited by J. Bransten, Russia: Moscow is becoming a developers dream, historians nightmare, RFE/RL, 25 March 2004. Estimates of her wealth vary: Forbes magazine, cited in the Moscow Times (13 May 2004), put her wealth at US$1 billion, while the Russian Finans magazine gave a figure of US$350 million (cited in Moscow Times, 15 April 2004). 21 The first Ikea opened in Moscow in March 2000 and in its first year achieved a turnover of US$100 million against a projected income of US$60 million after three years. In December 2001 it opened a second store in Moscow. This was followed by stores in the Leningrad oblast in December 2003 and in Kazan in March 2004. The company has plans to open a further three trading centres in Moscow and one in St. Petersburg. (Source: Ikea website.) Andrusz: From Wall to Mall 7

Conference: Winds of Societal Change: Remaking Post-Communist Cities University of Illinois, June 18-19, 2004

small, but growing cohort of would-be home-owners and small landlords that the developing mortgage market is oriented. The development of mortgage institutions and of a culture of long term borrowing lies firmly on the Russian Presidents policy agenda. While mortgages in Russia have been a topic for over a decade, outside Moscow a miniscule number of households have taken out mortgage loans. In most cases borrowers are chosen from those who pay taxes, since lenders do not take into account incomes which a significant proportion of the population derive from the informal economy or undeclared sources. But even if would-be borrowers declared their total earnings this would, according to Abel Aganbegyan, only raise average monthly earnings from 6,000 to 9,000 roubles (Aganbegyan, 2004)22. Low incomes will continue to constitute the main barrier to mortgage lending, even if the transaction costs involved in buying, borrowing and selling in the housing market are reduced and the law enabling lenders to foreclose on the property in case of mortgage default has been well tested23. However, Mr. Putins constituency is far from being confined to the housing demands of an emerging middle class and their need for better access to home loans and a more efficient mortgage system. His broader remit is to improve access to better accommodation in general for those for whom the cost of a mortgage is (and will remain) beyond reach; that is, for the majority of the population who live in flats, which are small in size, but dry, until recently well-heated throughout the cold season, and supplied most of the time with running water, gas and electricity, but for whom the cost of accommodation, its quality and its servicing remain a constant and aggravating problem (Argumenty i fakty (2003). It was this group that Putin was addressing in a television broadcast in June 2003, when he stated that, for the first time in a decade, considerably more funding would be allocated to the housing sector from the state budget, particularly for those living in dilapidated accommodation and needing to be re-housed24. But there are two groups who will not be affected by this additional funding: those living in communal flats (kommunalki) - and the worst off altogether, the totally homeless (Rubinshtein, 1998; Bransten, 2003; Dunn, 2003). The communal flat is a legacy of the socialist Revolution in 1917, when housing policy in the socialist city consisted of redistributing existing space by crowding a number of families (without housing) into single family dwellings mainly, but not only, belonging to the aristocracy and upper middle class, so that whole families lived in one room, which if very large would be divided to accommodate other households, all sharing kitchen and bathroom facilities25. As far as the government is concerned, the functioning of the market system (developers aided by local authority officials) will, through a natural process of gentrification, gradually see the disappearance of this type of tenure, although this might take a longer time in St. Petersburg where an estimated one-fifth of all households continue to live in kommunalki26. But, neither the

At the current exchange rate (1US$ = 29 roubles), this would mean a two income family would have around $US600 per month from all sources to service a mortgage. 23 The adoption of a law in February 2002 amending the 1998 Law on Mortgages provoked a member of the St. Petersburg Civil Law Centre to comment that this law is a further illustration of the legal incompetence of the legislators who drew it up with the exception of Article 78 which has removed the remaining obstacles to evicting mortgagers (and family members) who fail to meet their obligations to the mortgage lender. See: Law on Changes and Amendments to the Federal Law on Mortgages (11 February 2002) 24 V. Putin, 20 June 2003. Reported at: http://www.kremlin.ru/eng/priorities/21844.shtml. 25 Rapid urbanisation after 1929, and war-time destruction caused more households to live in kommunalki. 26 The evolution of this tenure and some of its essential features are captured in the following paraphrased description: For 30 years of his life until 1999 a St. Petersburg ethnologist, lived in the partitioned room off a long, dark corridor in a communal flat. In the early 1920s, the apartment -- originally owned by Mr. Utekhin's grandfather Andrusz: From Wall to Mall 8

22

Conference: Winds of Societal Change: Remaking Post-Communist Cities University of Illinois, June 18-19, 2004

market nor the state will come to the aid of homeless people ( ), who are widely regarded as the undeserving poor and part of the underclass to be exiled not to Siberia but to sink estates or to small towns and villages where they might have relatives and be able to live off a modicum of social capital. It would be a travesty to say that neither begging (poproshainichestvo) nor vagrants (brodyachii) were to be found in socialist cities, but to the extent that they did exist, their presence was regarded as a vestige of capitalism and, as such, excluded from public discourse; therefore, although sanctions had been introduced against them in the 1930s, it was not until 1960 that they came to be covered by Criminal Code for evading socially useful work and leading an anti-social, parasitical way of life (Pavlov, 1986). The number of people who are homeless unquestionably began to grow in the late 1980s and not only because state and society recognised and did not criminalise them for being homeless; in 1992 the head of a Russian charity estimated that there were 150,000 homeless people in Moscow and the Moscow oblast (Tretyakov, 1992). Various factors account for the increase, including: the collapse of the Soviet Union, which has given rise to refugees and forced migrants (Grafova, 2002)27; restructuring, which has caused unemployment, rising rates of alcoholism and drug addiction28; a dramatic decline in the number of new social housing units (Basargin et al. 2000)29; and the Law on (housing) Privatisation itself, which, by commodifying accommodation, encouraged some people to use criminal or un-ethical ways of gaining vacant possession; in 1998 it was estimated that apartment fraud was responsible for 30 per cent of those who had been made homeless in St. Petersburg in 1996 (Varoli, 1998)30. In the postsocialist Russian city the emergence of a speculative real estate market and increased housing hardship (including, homelessness) are correlated. The homeless phenomenon is closely associated with another: street children (besprizorniki). Estimates of their number vary from the very vague, about 2.5 million

-- was home to 56 people. By the late 1960s, when he was born, it accommodated a flexible 35 people and today 1620 people. Roughly one-fifth of the population in the older part of the city still live in such flats26, compared with their peak in the 1930s, when some 68 percent of the population in St. Petersburg lived in such apartments a form of accommodation which Utekhin still speaks of as being the key to Soviet civilization where the elements of everyday [Soviet] life are still present, in the most concentrated way. Ironically, the perception that some tenants have of life in this sort of flat could be interpreted as reflecting the content of an ideal community, one in which, "being evaluated every moment, from head to foot: what you are wearing, where your mother works, who comes to visit you, what you eat, whether you have spare time, what clothes you wash, and what your underwear looks like hanging on the clothes line." For Mr. Levchenko, a philologist from Estonia, who spent five years in a dormitory at the University of Tartu, life in the kommunalka, where he pays a monthly rent of 300 rubles (US$10) for a room does not pose any hardship. Neither does it for Alisher Sharipov, assistant to the director of the library at the European University, who lives on the other side of a partition, in a space the size of a walk-in closet for whom the room is a bargain because: "I have very few things. I am not obligated to anyone. I have no history here -- neither a past nor a future. Such as it is, it is a kind of freedom". 27 Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, 8.6 million people have migrated to Russia, of whom only 1.6 million have the official status of refugee or forced migrant. See: Vserossiiskii chrezvychainyi syezd v zashchitu migrantov, Moscow, 20-21 June 2002 28 On 19 March 2002, Valentina Matvienko, a Deputy Prime Minister announced that the official number of drug addicts in Russia exceeded 1.5 million, representing an eight-fold over the last decade, ITAR-TASS. 29 The proportion of all new units erected by the state and municipal authorities declined from 80 per cent in 1990 to 20 per cent in 1998, of which 9 per cent was contributed by federal level enterprises. 30 As early as 1994 the Moscow city government passed a resolution establishing a service to protect elderly tenants from being defrauded by individuals offering them a variety of medical and other services in exchange for the title to their flats. See: Resolution No. 709, 30 August 1994, On social support for single elderly citizens and guaranteeing them social services in exchange for surrendering their housing space in Moscow. Andrusz: From Wall to Mall 9

Conference: Winds of Societal Change: Remaking Post-Communist Cities University of Illinois, June 18-19, 2004

(Alekseyev, 1998:147), to the over-precise, such as the 611,034 children without parental care, of whom 337,527 were housed in a variety of institutions made by UNICEF (UNICEF, 1997). The vagueness of the former and the precision of the latter are grounds for scepticism about these magnitudes. While Stephenson (1998) added a useful corrective to these figures, estimating that at any given point in time there were not more than 800 homeless children living in the streets of Moscow, in 2001 the figure cited at a lecture in the Kennan Institute was 100,000 (Dresen, 2001). By 2004 the city government estimates that there are now about 40,000 children living the streets of Moscowcompared with 25,000 in 1999, of whom 6 per cent were from the city itself. By 2001 there were 33,000 and 20 per cent were from Moscow (Page, 2004). Conclusion Unlike some idealised accounts of the socialist city (Davidow, 1976) urban marginality, represented by homelessness, street children, beggars, street crime, drug taking, did exist prior to 1990; now, however, it is on a scale that Robert Park would recognise. Moreover, it is not always just the scale that is different: Although criminal gangs of young people are not a new phenomenon in Russia, today, amongst the proliferation of youth sub-cultural groups are those identifying themselves as skinheads or nazis, claiming that the aim of their groups is to clean up Russia from black people (negri) and people from the Caucasus and Central Asia (churki); they feel that their ethnic prejudices are legitimated by the harassment to which they see members of minority groups subjected by militiamen (Zorkaya, 2002). The emergence of numerically significant marginal groups is giving rise to their concentration alongside ethnic minorities in dilapidated buildings and small neighbourhoods in the central districts, such as Shkapina, in the historic centre of St. Petersburg. It was here in autumn 2003 that a German director decided to set his film Der Untergang. The site was chosen because the producers felt that the area contained good examples of Art Nouveau architecture31 and because, apart from a liberal sprinkling of bricks and burned-out cars, and erecting German signs and employing smoke machines, they had to change little to make the area look like the ruined Berlin in April 1945. A large number of immigrants particularly from the Caucasus but also from Central Asia, who own and are serviced by shops which meet their own cultural needs, live in the neighbourhood. But its social content and fabric are beginning to change. Shkapina has become popular amongst artists who have begun to squat abandoned buildings32 and convert them into studios, thus beginning the gentrification process. The decision by St. Petersburgs municipal government in December 2003 to redevelop the former industrial neighbourhood, will involve demolishing run-down housing, relocating the residents currently

The producers had investigated other cities, including Prague, Kiev, Sarajevo and Copenhagen, before settling for St. Petersburg. 32 Although an exceptionally rare phenomenon, examples of squatting can be found in both socialist and postsocialist cities. In 1993, a group of residents squatted a new, uninhabited block of flats in the Mitino district of Moscow. (See: Yakov, V , No. 28, 13 February 1993 ) In the case of as socialist city, one researcher traced the process of a case of an East German familys application for improved housing, which culminated in the family squatting a newly built flat in 1978 in Rostock. The family was respectable and had met local officials and corresponded with them. After several years of rebuffs they moved into (squatted) a vacant apartment. See: J.Hackeling, Remembering Ordinary Agency Under East German State Socialism: Revelations of the Rostock District Record, 1978-1989, in P. Gready (ed.) Political Transition. Politics and Culture,, Pluto Press, London, 2003, pp.183-197. Andrusz: From Wall to Mall 10

31

Conference: Winds of Societal Change: Remaking Post-Communist Cities University of Illinois, June 18-19, 2004

living on the 4.5-hectare site and constructing a new retailing and entertainment complex at a cost of over US$36 million; the entire project is scheduled for completion by 2007. That, at least, is the plan. The social polarisation of the post-socialist city (Goskomstat, 2002: 187)33, which is evident in the extremes of the small, new aristocracy in their usadby and gentrifed enclaves in the city on the one hand, and the huge population of poor and very badly housed people, on the other, provides a framework for observing within the post-socialist city the emergence of a new economy and the Mall. The post-socialist city as a productive unit For over a decade, the development of small and medium sized enterprises (SMEs) in postsocialist cities have been promoted by every major international body (OECD, IMF) and national donors (EU, US AID, DfID) as the panacea for the unemployment caused by restructuring, privatisation and the down-sizing of under-capitalised manufacturing industry. To the extent that entrepreneurs are emerging, their presence is mainly felt in the service sector. Apart from cafes, restaurants, small retailing outlets and estate agents, the information society creates opportunities for an individuated workforce, operating as independent micro-economies within the sector in such fields as information technology (website designers), financial services (accountants, legal and business advisors) and culture and the arts (fashion design, film making) all of whom are beginning to emerge in post-socialist cities. Individuals in the modern workforce, lacking job security, adapt multi-skilled profiles, engaging simultaneously in a number of projects - to deliver products as did bespoke tailors in a previous era. In this creative segment of the, general economy, whose workers are now credited with being members of a creative class (Florida, 2002a, 2002b), a person can no longer expect to spend a life in a stratified but secure workplace but instead for ever revolve in a network of sociability, one in which the individual has to spend considerable effort engaged in selfpromotional strategies. Lacking social security, they have to enter into contracts to buy accommodation and health insurance and take out private pensions and, pay, when necessary, for further education or training in order to improve their marketability. The form that the postsocialist city will take will be substantially affected by the re-commodification of health and education and the States retreat from social housing; and by the reconfiguration of policing so as to reinforce marginalisation and the promotion of plans to annihilate those residents deemed to be the human equivalent of blight34. These trends might give rise to a search for new uses of space to accommodate the social networks through which individuals derive and exchange information about work opportunities and through which they share their mutual costs. Tracts of derelict land, often harbour-side or railway termini or junctions, their related small manufacturing plants now closed, are transformed through a process of gentrification as older empty are converted into warrens of business units. The demand for office and telier

33

In 1991 the poorest 20% of the population earned 11.9% of total income compared with the richest 20% who earned 30.7%. The respective figures for 2001 were 5.9% and 47.0% respectively - evidence that the poor are becoming poorer in relationship to the richest section of the population. 34 The mayors of both Moscow and New York seem to have adopted similar policy stances to homeless people and rough sleepers, although the latter has perhaps been more explicit in identifying them as among the culprits responsible for negatively effecting the quality of life of the middle class and thus to be subjected to the zero tolerance means test. Andrusz: From Wall to Mall 11

Conference: Winds of Societal Change: Remaking Post-Communist Cities University of Illinois, June 18-19, 2004

space and rising rents are a motor force driving the capitals economy35. At the same time, rapidly rising property values and rents make it increasingly difficult for the independent professional, or creative artist to find affordable space to rent. In the economically developed countries of the EU, many freelance, independents are compelled to return to being either wage labour in a large company on a full-time basis, or, as is becoming more common, full-time, project-based, contracted labour for one or more companies. In the post-socialist cities such options are still rare, leaving many qualified individuals with little or no alternative to remaining unemployed, taking (less skilled) jobs incommensurate with their education, or (e)migrating for a short period in order to gain experience and accumulate a modest amount of material (and social) capital to be invested in the post-socialist city of their origin. The likelihood that a town, city or region will thrive in the information society is coming to depend on how well it manages to re-image itself, so that people see it as an attractive place to visit in order to consume or to work or to enjoy as tourists. In an age of global tourism, advertising and marketing, and when jobs are being lost in the traditional agricultural and manufacturing sectors, the metropoles in the region struggle for their names to be recognised as destination points on the world stage. In attempting to do so, cities such as Moscow, St. Petersburg, Prague, Budapest and Warsaw more than most others reveal themselves to be sites for an intense struggle of interests and values (Simpson, 1999)36: Modern cities compete with each other by means of images but in doing so are involved in the cultural commercialisation of space which, while aimed at creating a particular identity, debases its cultural value. Private companies for themselves and public authorities for their citizens devote mounting resources to developing strategies for the production, distribution and consumption of images of what their cities have to offer. They have to promote and package their histories and traditions for tourists, affluent residents and talented individuals rich in human capital, as they seek to anchor themselves in a global space of flows, presenting themselves as unique and attractive. Yet, paradoxically, their uniqueness has to be combined with modes of retailing and marketing which make them the same as their competitor cities and shopping-entertainment spaces. Malls and shopping arcades combine to form entertainment cities, places where some entertainment or cultural event creates its own important source of added value to the city and to shopping itself (Bittner, 2001: 357-364). Conservation, coloured by retro-socialist or retro-presocialist chic, articulates with tourism and the shopping experience to become a valuable agency for the commercial-colonization of the historic core of the post-socialist metropoles. Regional capital cities, such as Kostroma on the Volga37, which consider that they have a

35

By 1994 a building boom was already evident in Moscow. See: A. Tolkonnikov, Stroitelnye bum neizbezhen. Marketing stroitelnykh materialov, in Delovoi Mir, 21-27, March 1994, pp. 10-11. 36 Reklama uroduet Nevskuyu perspektivu, Argumenty i Fakty, No. 38, September 2003: During the tercentenary celebrations all the usual advertisements along Nevskii Prospekt were taken down in order not to spoil the view, making a walk along it so enjoyable. Now that all the guests have gone, all these grubby rags are back again, making it impossible to see the Admiralty when standing on Vostanaya Ploshchad at the bottom of Nevskii Prospekt. Each time the city authorities attempt to regulate neon light, banner and billboard advertising it meets strenuous opposition from vested economic interests. And, yet, something does need to be done to preserve the value of Petersburg as a cultural capital and as a tourist attraction. For the sake of deriving an income from advertisements, we risk losing much more from frightening away visitors to the city. 37 Kostroma (population 280,000) is located 186 miles east of Moscow on the left bank of the Volga River. It was here that the young boyar, Mikhail Romanov, was hiding in 1613, when the All-Russia council (Zemski sobor) came to plead that he accept their election of him as the new tsar. The town hero is Ivan Susanin (the subject of Glinkas opera), who saved Mikhail Romanov from a Polish detachment by leading them into a forest at the cost of his own life. The original monument (where Susanin is depicted with the tsar) was torn down by the Communists and Andrusz: From Wall to Mall 12

Conference: Winds of Societal Change: Remaking Post-Communist Cities University of Illinois, June 18-19, 2004

marketable value are also scrutinising their citys cachet. The relevance of issues such as image, malls and event cities, which might seem futuristic, is evident in the crystallisation of housing classes and in the highly visible socio-spatial differences found in the post-socialist metropolis. It is against the potential danger posed by the underclass and marginalised people (Trenin, 2004:14)38 to those living in their gated housing and small enclaves of gentrified housing, and to those who visit the entertainment city that the state, private corporations and residents associations are beginning to deploy surveillance cameras to supplement the security guards who patrol both outside and inside buildings in order to strengthen defensible postsocialist space. As in other capitalist countries the defence of luxury and of the person has given birth to an arsenal of security systems and an obsession with the policing of social boundaries through architecture (Davis, 1992). This technology, and the concepts and personnel behind it are readily imported into post-socialist cities to provide personal and public security against ordinary criminals and now against the growing threats presented by real and imaginary global terrorists39. Ironically, it is not the super-rich the new plutocracy that is most at risk, but the aspirant lower middle class who visit the mall. The post-socialist city as a consumption unit: The Mall While the almost impregnable Wall kept its flock in a utopian paddock of a collectivist culture, the transparent, porous boundaries of the Mall superintend a banquet of personal consumption. Modern shopping centres, Malls40, which have begun to appear in a few of the major cities in the region41 incorporate small specialised shops, department stores, supermarkets, restaurants, bars, cinemas and other forms of entertainment. In blurring the boundaries between shopping (buying goods), entertainment and browsing as a leisure activity, the Malls multifunctionality makes it a

replaced with a more appropriately socialist one in 1967. In the 17th century Kostroma was the third largest town in Russia after Moscow and Yaroslavl. In 1773 most of the town, including the kremlin, burned down, which allowed Catherine the Great to turn the city into a showpiece for her enlightened design principles, having it rebuilt according to then modern town planning methods with streets radiating from a single focal point near the river. Kostroma is today the only Russian city that retains its original layout from this period, with the city centre one of the finest examples of late 18th century Russian architecture. It is a model case for study as a post-socialist city. 38 Seen from the 1913 perspective, it is safe to conclude that, then as nowwidespread poverty is the principle threat. Dmitri Trenin is Director of Studies at the Carnegie Moscow Centre.

39

In Russia, the terrorist threat in cities is a very real one and is a potential threat in Poland as a result of its contribution of 2,400 troops to the coalition forces in Iraq, the fourth largest contingent after the USA (135,000 ), the UK (8,700) and Italy (3,000).

The first self-contained shopping centre - the shopping mall was opened in a suburb of Minneapolis in 1956, the brainchild of a Viennese architect, Victor Gruen. A space, which would have all the features of a traditional city with its alleyways, streets, courtyards and squares, would benefit both consumers and retailers and through its fostering of a sense of shared community, would tackle social problems The technological key to the idea was the development of all year round air conditioning. See: M.J.Hardwich, Mall Maker: Victor Gruen, Architect of an American Dream, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2003. 41 In December 2002 Ikea opened a mega-mall in Moscow, containing a hyper-market, 250 shops, 2 km. of shop fronts, a skating rink and Russias largest cinema complex and expects 25-40 million visitors annually. The tendency for malls to develop in some cities and countries to a greater or lesser extent than others, will partly reflect cultural preferences. The consumer culture in Germany cannot really be compared to that of the USA. At present there are 2,494 shopping malls in the USA, while in Germany there are only 67. In comparison Japan has 439; Great Britain, 778; and France 202. Andrusz: From Wall to Mall 13

40

Conference: Winds of Societal Change: Remaking Post-Communist Cities University of Illinois, June 18-19, 2004

public space like a piazza (Jameson, 2003)42. The Mall is a place in which most objects within it are inscribed with globalised commercial images43 and messages. The logo and the brand name are no longer restricted to material products (Benetton, Coca Cola, Mercedes), but are extended to services (Visa) and experiences (IMAX, Hard Rock Caf). But while investors, who finance each new Mall, insist that the usual globally branded companies should be integral to any new retail entertainment project44, designers and executives from the themed entertainment industry want the entertainment based (re-)development to strive for a marketable identity based on local culture, history and identity (Hanningan, 2001:408). The design and technology used by Rem Koolhaas in the Prada flagship boutique in Lower Manhattan, which is a combination of technical innovations, marketing strategies, imaging concepts and social analysis(Hannigan, 2001:405), has not only been imitated as, for example, in the recently opened restaurant, Zov Ilicha in St. Petersburg45, but is being subverted by faked labelling and local brands posing as global. Funded by wealthy private investors, the ideology of the Mall, as a high status palace of consumption, is never to aspire to cater for a mass market; that remains the task of the shop in the ground floor space of a block of flats, the kiosk and the ethnically heterogeneous bazaar and open-air market. Since the economies in which post-socialist cities are located are considerably poorer than those of OECD members the significance of the Mall has to be sought not only in the function it fulfils for a small, more prosperous group of people; it is a flagship of societies where goods are coming to be consumed less for the sake of their utility value and much more for their association with the pleasure of the shopping experience itself, for the symbolic significance attached to branded products and to specific lifestyles. Nothing in the contemporary city is quite what it seems: railway stations have become car maintenance workshops or museums and churches are being turned into theatres and night clubs, prisons into hotels. In the USSR, cathedrals were visited as museums of atheism. If airconditioning was the technological precondition for the Mall, it is now indispensable for some major religious sites, where visitors experience, or search for, spirituality or consume religion as spectacle. In the Cathedral of Christ the Saviour, a web-site run by Alfa Laval informs browsers that the air remains fresh regardless of the number of candles lit and visitors present, which is not surprising at all: the new cathedral was built using the most advanced technologies. The sophisticated air conditioning system provides a constant temperature inside the cathedral in

42

In 1994, the mall officially replaced the civic functions of the traditional downtown. In a New Jersey Supreme Court case regarding the distribution of political leaflets in shopping malls the court declared that shopping mallshave replaced the parks and squares that were traditionally the home of free speech, siding with the protesters who had argued that a mall constitutes a modern-day Main Street. Harvard Design School, Project on the City, Cologne, 2000 cited by Jameson, p.70 43 In the words of Guy Debord, the final form of commodity fetishism is the image, which Jameson sees as being the take-off point for [situationists] theory of so-called spectacle society, in which the former wealth of nations is now grasped as an immense accumulation of spectacles..[with the result that] the commodification process is less a matter of false consciousness than of a whole new life style, which we call consumerism. See: Jameson, p.78. 44 At the breakneck speed demanded by the [internet] freeway only brand franchise signals can be apprehended anything else requires too great an investment of time to check and verify. When youre travelling this fast.difference constitutes an unnecessary detour. B. Mau, Life Style (London, Phaidon Press, 2000 cited by J. Hannigan, Place Making and Story-Making in the Even City, in R. Bittner p. 407 45 Zov Ilich (Lenins Mating Call) is a new restaurant in St. Petersburg, described a an unholy mix of Soviet chic and luxurious dining, where busts of Lenin sit on tables amidst television monitors showing alternatively delegates standing and applauding at a 1930s party conference and an erotic video. Andrusz: From Wall to Mall 14

Conference: Winds of Societal Change: Remaking Post-Communist Cities University of Illinois, June 18-19, 2004

summer and winter regardless of the weather. A dozen computers monitor warm air circulation in every part of the cathredal. Not many buildings in Russia have such an efficient heating system like the cathedral does with the key components provided by Alfa Laval. The 1,200 capacity assembly hall for meetings of the Holy Synod is frequently used for classical music concerts and for New Years celebrations for children; a dining hall capable of catering for 1,500 guests is integrated into the cathedral. A smaller church with a museum situated in its gallery lies behind the main cathedral. In keeping with the post-modern era, the new cathedral was designed both as a holy place and as a tourist attraction capable of holding 7,000 visitors at a time. Apart from being a modern, fashionably-equipped building, it plays its main role as a holy place open to people of different faiths and lifestyles (here, 2004). This website description of a religious shrine makes it almost indistinguishable in some of its features from the Mall. The post-socialist city rebuilds its pre-socialist (pre-war) churches, turns its rich art-deco and socialist realist railway stations into tourist destinations in their own right places where the homeless, vagrants and nomads congregate. The church, the mall, the airport and the station convey a sense of perpetual movement, yet, the catch phrase that individuals no longer have roots but terminals expresses a reality for only a fraction of the postsocialist citys population46. The cultural ambience and imagery found in Zov Ilicha supports the thesis that cities, regions and countries that are open to diversity are able to attract a wider range of talent by nationality, race, ethnicity, and sexual orientation than those that are relatively closed (Florida, 2002b: 743). Florida uses a high incidence of gay people in the population as a proxy for diversity in the USA because the gay population is a segment of the population that has long faced discrimination and ostracism; therefore, the presence of a comparatively large gay population serves as an indicator of a region that is open to various other groups47. Highly educated, young workers are also attracted to vibrant (cool) places48 such as Zov Ilicha. Thus a city that is diverse [open] is able to attract and retain talented people [i.e. individuals with high levels of human capital], who in turn attract high-technology industries which generate higher regional incomes (Florida, 2002b:753). The conclusion drawn from this is that, in order to foster the growth of cities or regions, planners at different government levels should adopt programmes directed at making themselves attractive to human capital by supporting and enhancing diversity (Florida 2000b:754), rather than just focussing on making themselves attractive to companies. Even if the evidence from the USA (and possibly elsewhere) upholds Floridas hypothesis, it might be necessary to propose that a different social group serve as a proxy indicator for diversity and openness in the post-socialist city. Perhaps diversity is not the

46

According to Pivovarov (2001) between 1951 and 1980, 37.8 mln. people migrated from rural areas into towns; such numbers could not easily be accommodated in an urban environment, hence the adaptation of rural inhabitants to the urban way of life and their assimilation of urban culture and the corresponding system of values and norms of behaviour are still far from complete.Herein lies the most important difference between the modern stage of urbanisation in Russia and the WestRussia remains, to a large extent, a rural country with most urban residents retaining deep rural roots, preferences and emotional attachments. While this is a contentious view, which probably exaggerates the situation, it is a perspective that has to be taken into consideration when exploring the post-socialist city, at least in Russia and probably most other republics of the FSU. 47 Florida 2002b p.747 By extension, he believes that, since openness to immigration is a key factor in innovation and economic growth, the relative homogeneity of the populations in Japan and German explains the relative stagnation of their economies. 48 This is coupled with another innovation a coolness index, derived from the number of cultural and nightlife amenities. Florida (2002b) p.744 Andrusz: From Wall to Mall 15

Conference: Winds of Societal Change: Remaking Post-Communist Cities University of Illinois, June 18-19, 2004

critical issue; instead, gay households may be seen as representing another (Weberian) minority, who, experiencing ostracism and a degree of social exclusion, work hard to gain educational qualifications and then put these to work in the capitalist world, which rewards them well with high incomes. The fact that they are hedonists (and not Calvinists) and therefore spend their earnings (in the cool environment) rather than invest them, still benefits capital, which provides them with temples of pleasure (culture, amenities). While, it is questionable whether openness, in the sense used by Florida, will be the criterion for attracting talent and high growth firms, coolness is almost certainly one of several factors in making a city more attractive to talented individuals. For instance, on the eve of membership of the EU, one Latvian fashion designer, who is keen to create a uniquely Latvian aesthetic, referred to Riga as the hottest city of the north whose vibrancy owes much to its local talented artists who are blending the influences of traditional roots with the citys modern, cosmopolitan atmosphere (Observer Magazine, 2004)49. This view, itself a marketing image generated by entrepreneurs and local politicians, contrasts with the socialist period when, moving between cities, peoples residential preferences were conditioned by factors such as climate, the urban infrastructure and the status of the city in administrative terms, since its ranking determined the volume and quality of services available, including food products and consumer goods50 (Vasilev et al. 1988). Compared with socialist cities, which had more or less planned economic and administrative profiles as part of a grand schema for the allocation of resources and functions by the state, each post-socialist city now has to compete with all other cities for inward capital investment, consumers and tourists. If they are successful in projecting themselves as possessing an aesthetically satisfying environment for urban (and, as an additional bonus, cosmopolitan) elites, they survive and thrive, while the others are left to ponder the dearth of symbolic capital, decreasing resources and a diminished urban prospect (Cuthbert, 2003:6). It falls to local governments to devise ways of promoting an appealing image of their city that can be transmitted on to the regional and world stage. Conclusion The de-industrialisation of Western economies in conjunction with a reconfiguration of the economies of post-socialist cities is giving rise to major changes in the organisation and use of space within them. The intentional destruction of the built environment offers considerable opportunities for the investment of the surplus capital that becomes available with deindustrialisation. Private investors, both domestic and foreign, have for over a decade begun to advance into selected post-socialist cities in order to meet capitalisms demonic appetite to build and rebuild (Clarke, 2003:29) especially in central city areas from which manufacturing companies are forced to move, thus enhancing the value of the centre. The Palace of Culture and Science in Warsaw (Dawson, 1999), a controversial gift from Stalin to the people of Warsaw, the third highest building in Europe, illustrates how the location of a vast real estate capital asset is possibly more valuable than the building. Containing a conference and exhibition centre, theatres and cinemas, rented office space, shops, cafes and restaurant, post office and bank and

49

Almaty can claim a similar status in Eurasia; it too has a thriving nightlife, boasts 100 casinos and international clubs all resting on the spending power flowing from the oil and gas industry. 50 This casual understanding of choice of town was upheld by an examination of the card file on housing exchanges held by the Moscow Bureau of Housing Exchanges in the late 1980s. See Vasilev. Andrusz: From Wall to Mall 16

Conference: Winds of Societal Change: Remaking Post-Communist Cities University of Illinois, June 18-19, 2004

parking for 800 cars, the building would seem to have much to offer; though, today, it might appear as a Mall before its time, its name and original purpose give it away. Buildings and monuments embody the values of a particular period and regime; they are perceived by successor regimes as being the visible embodiment of those values and may be the subject of obloquy and derision before being finally denounced and demolished. Attacking a monument, first by discussing it in the media and other arenas, and then destroying it represents a way of attacking the regime and symbolically cleansing the place itself representational of society - where it is located. Paradoxically, in doing so, reference points within the historical memory are removed and the lessons that had been learned are lost. In order to prevent this from happening, the memorial may be restored, but the didactic purpose will have been extracted, and, instead, the replacement is treated primarily as a tourist attraction, as something to be incorporated into, for example, the Berlin experience where it might be interpreted as the Berlin Wall experiment. But, for many, Berlin remains divided, as is the society, as is the region: The final paragraph of a German web-site dedicated to the Wall states: Although only few places remain where parts of the wall and watch-towers can be seen, an invisible wall divides the country in two. The disunity between the East and the West is even felt in Berlin to this day. The German people must overcome their differences in history, education, upbringing, language and culture51. The journey from Wall to Mall can be seen, experienced and interpreted in different ways. At the very least it is a journey between two different types of city socialist and post-socialist. The final irony will be the creation of a mall around a fragment of the wall, one symbol embracing another.

51

www.die-berliner-mauer.de/en/89.html

Andrusz: From Wall to Mall

17

Conference: Winds of Societal Change: Remaking Post-Communist Cities University of Illinois, June 18-19, 2004

References

Aganbegyan, A. (2004), Pochemu nam ne nravyatsya bogaty, in Argumenty i Fakty, no. 18, May Alekseyev S., Kalamanov, V., Chernyenko, A. (1998) Ideologicheskiye Orientiry Rossii, in Kniga i Biznes, Vol 1 Argumenty i fakty (2003), Byli o zhile. Skolko nado platit za kvartiru, no. 38, September Bahro, R. (1977), The Alternative in Eastern Europe, trans. D. Fernbach (London, New Left Books). Basargin, A.F., Rakhlin, A.E. & Andrusz, G. (2000), Novyi podkhod k zhilishchnoi politike v Rossii, in Promyshlennoe I grazhdanskoe stroitelstvo (PGS), no. 10, pp.7-9 Bater, J., Amelin, V. & Degtarev, A. (1998), Market Reform and the Central City: Moscow Revisited, in Post-Soviet Geography, 39 (1), pp.1-18 Bittner, R. (2001), The City as an Event, in Bittner, R. (Ed), Die Stadt als Event. Zur Konstruktion urbaner Erlebnisraume (Event City), (Frankfurt/New York, Campus Verlag Edition Bauhaus) Bliznakov,M. (1990), The Realisation of utopia: Western technology and Soviet avant-garde architecture, in Brumfield, W. (Ed), Reshaping Russian Architecture (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press) Bliznakov, M (1993) Soviet housing during the experimental years, 1918 to 1933, in Brumfield , W. & Ruble, B. (Eds), Russian Housing in the Modern Age (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press) Bransten, J. (2003), Russia: City Anniversary Changes Little for Residents of St. Peterburgs Kommunalki, RFE/RL, 6 June 2003 Castells, M. (1989), The Information City (Oxford, Blackwell) Castells, M. (1996), The Rise of the Networks Society (Oxford, Blackwell) Chihireva, N. (2002) Airbrushed Moscow. The Cathedral of Christ the Saviour in N. Leach (Ed.) The Hieroglyphics of Space. Reading and Experiencing the modern metropolis (London, Routledge) Clarke, P. (2003) The Economic Currency of Architectural Aesthetics in Cuthbert (Ed.) p. 29 Cuthbert, A. (Ed.), (2003) Designing Cities. Critical Readings in Urban Design (Oxford, Blackwell) Davidow, M. (1976), Cities without Crises (New York, International Publishers) Davies, R.W. (2003) Introduction to E.H.Carr, The Russian Revolution. From Lenin to Stalin (19171929), (Basingstoke, Palgrave MacMillan) Davies, N. & Moorehouse, R. (2002) Microcosm. Portrait of a Central European City, (London, Jonathan Cape)

Andrusz: From Wall to Mall

18

Conference: Winds of Societal Change: Remaking Post-Communist Cities University of Illinois, June 18-19, 2004

Davis, M. (1992), Fortress Los Angeles: the militarisation of urban space, in Sorkin, M, (Ed), Variations on a Theme Park: The New American City and the End of Public Space (New York, Hill & Wang) Dawson, A. (1999), From Glittering Icon to., in The Geographical Journal, vol. 165, July, pp.154-160 Dresen, J. (2001), Empowering through Victimisation: Moscows Homeless Children, Lecture at the Kennan Institute of the Woodrow Wilson International Centre, Washington, D.C. 25 October Dunn, J. (2003), Russias living nightmare: Communal dwellings in St. Peterburg, Sunday Times (UK), 27 July 2003. Esping-Andersen, G. (1990), The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism (Cambridge, Polity Press) Evans, R.J. (1997), In Defence of History (London, Granta) Florida, R. (2002a), The Rise of the Creative Class (New York, Basic Books) Florida, R. (2002b) The Economic Geography of Talent, Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 92(4), pp743-755. French, R. & Hamilton, F. (1979) Is there a Socialist City? In French, R. & Hamilton (Eds), (1979) The Socialist City: Spatial Structure and Urban Policy (Chichester, John Wiley) Goldman, M. (2003), The Piratisation of Russia. Russian Reform Goes Awry (London, Routledge) Gradostroitelnyi kodeks Rossiiskoi Federatsii, (2003) (Moscow, Os-89), 3rd edition. Gritsai, O. (1997), Business services and restructuring of urban space in Moscow, in GeoJournal, August, 42(4), pp.365-376 Goskomstat RF (2002), Rossiiskii statisticheskii ezhegodnik (Moscow) Grafova, L. (Ed) (2002), Zachem Rossii Migranty. Sbornik luchshikh publikatsii zhurnalistov Informatsionnogo Agenstva Migratsiya (Moscow, Forum pereselencheskikh organizatsii) Hamilton, I. (1999), Transformation and Space in Central and Eastern Europe, in The Geographical Journal, vol. 165(2), July, pp.135-144 Hamm, B. (Ed) (1984), Urban and Regional Sociology in Poland and W. Germany. Proceedings of the First Polish-German Symposium on Urban and Regional Sociology, Bad Homburg, 17-20 October 1982 (Bonn, Bundesforsshungsanstalt fur Landeskunde und Raumordnung) Hamm, B. & Jalowiecki, B. (Eds) (1984) Urbanism and Human Values. Proceedings of the Second Polish-German Symposium on Urban and Regional Sociology, Kazimierz nad Wisla 11-15 September 1983 (Bonn, Bundesforsshungsanstalt fur Landeskunde und Raumordnung) Hannigan, J. (2001), Place Making and Story-Making in the Even City, in R. Bittner op.cit. Harloe, M. (1996) Cities in the Transition, in Andrusz, G., Harloe, M. & Szelenyi, I. (1996) Cities after Socialism (Oxford, Blackwell Publishers)

Andrusz: From Wall to Mall

19

Conference: Winds of Societal Change: Remaking Post-Communist Cities University of Illinois, June 18-19, 2004

Hobsbawm, E. & Ranger, T. (Eds.) (1983), The Invention of Tradition, (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press) Jameson, F (2003), Future City, New Left Review, 21, Second Series, May-June 2003 Jezernik, B. (1998), Monuments in the Winds of Change, in International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, vol. 22 no.4. pp. 582-588) Kishkovsky, S. (2003) The Czar Didnt Sleep Here, The New York Times, 9 January Kopp, A. (1970), Town and Revolution. Soviet Architecture and City Planning, 1917-1935, trans. By T.E.Burton (New York, George Braziller) Leach, N. (Ed.) (2002) The Hieroglyphics of Space. Reading and Experiencing the modern metropolis (London, Routledge) Marcuse, P. (1996), Privatisation and its Discontents, in Andrusz, G., Harloe, M. & Szelenyi, I. (1996) Cities after Socialism (Oxford, Blackwell Publishers) Marx, K. & Engels, F. (1848/1962) Manifesto of the Communist Manifesto, in Selected Works in Two Volumes (Moscow, FLPH) vol.I, pp.98-137 The Sunday Observer (Observer Magazine) (UK) (2004) In from the Cold, 11 April OFlynn, K. (2004), Fast-Changing Centre is Squeezing Out Locals, in The Moscow Times, 13 January Ovcharova, L. (2002), Social Policy in Changing Russia, (Independent Institute for Social Policy, Moscow) Page, J. (2004), Life on the edge for Moscows 40,000 street children, in The Times (UK), 14 February. Paperny, V (1993), Men, women, and the living space, in Brumfield , W. & Ruble, B. (Eds), Russian Housing in the Modern Age (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press) Pavlov, V.G. (1986), Istoriya razvitiya sovetskogo zakonodatelstva po borbe s litsami, vedyshchimi parazitischeskii obraz zhiszni (1917-1960), (Leningrad, Politicheskaya rabota MVD) Pivovarov, Yu,. (2001) Urbanizatsiya Rossii v XX veke: predstavleniya i realnost, Obshchestvennye nauki i sovremennostno.6, pp.101-113 Ray L. (1996), Social Theory and the Crisis of State Socialism (Cheltenham, Edward Elgar) Rubinshtein, L. (1998), Kommunalnoe chtivo, in Itogi, 12 May, pp. 54-59 Ruble, B. (1990) Moscows revolutionary architecture and its aftermath: a critical guide, in Brumfield, W. (Ed), Reshaping Russian Architecture (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press) Ruble, B. (1995), Money Sings. The Changing Politics of Urban Space in post-Soviet Yaroslavl (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press) Samuel, R. (1996) Theatres of Memory: Past and Present in Contemporary Culture (Verso, London)

Andrusz: From Wall to Mall

20

Conference: Winds of Societal Change: Remaking Post-Communist Cities University of Illinois, June 18-19, 2004

Scott, C. (2004), Overseas Property: In from the cold in Sunday Times (UK), 9 May 2004 Simpson, F. (1999), Tourist Impact in the Historic Centre of Prague: Resident and Visitor perceptions of the Historic Built Environment, in The Geographical Journal, vol. 165, no. 2 July, pp. 173-183 Smith, D. (1996) The Socialist City, in Andrusz, G., Harloe, M. & Szelenyi, I. (1996) Cities after Socialism (Oxford, Blackwell Publishers) Stephenson, S. (1998), Detskaya besprizornost: sotsialnye aspekti (po materaliam sotsiologicheskogo issledovaniya v Moskve 1997-1998), in Sotsiologicheskie issledovaniya v Rossii, 4, (Moscow, INION RAN) Szelenyi, I. (1983), Urban Inequalities under Socialism, (Oxford, Oxford University Press) Szelenyi, I. 1996) Cities under socialism and after, in in Andrusz, G., Harloe, M. & Szelenyi, I. (1996) Cities after Socialism (Oxford, Blackwell Publishers) Taranovskaya, M.Z., Duranina, I.S. & Kviatkovskii, I.A. (1979), Tvorchestvo leningradskikh arkhitektorov (Leningrad, Stroiizdat) Trenin, D. (2004), What You See Is What You Get, in The World Today (published by the Royal Institute of International Affairs), vol. 60. No. 4, April 2004. Tretyakov, E. (1992), Lyudi bez krova, in Soprichasnost no. 1 UNICEF (1997) Children at Risk in Central and Eastern Europe: Perils and Promises (International Child Development Centre) cited by Stephenson (1998) Varoli, J. (1998), St.Petersburg Coming to Grips with Homeless Problem, RFE/RL, 18 February 1998 Varoli, J. (2003), Raising High the Russian Beams in New York Times, 9 January Vasilev, G., Sidorov, D., Khanin, S. (1988), Vyyavlenie potrebitelskikh predpochtenii v sfere rasseleniya, in Vestnik Moskovskogo Universiteta, seria 5, geografia, 1988, 2, pp.41-47

Zorkaya, N. Dyuk, N. (2001), Tsennosti i ustanovki rossiiskoi molodyozhi, (Moscow, VTsIOM), http://www.polit.ru/docs/623520.html

Andrusz: From Wall to Mall

21

You might also like

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)