Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Africa

Uploaded by

Sarveshwar Garg0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

30 views5 pagesAid worker and diplomat Giles Bolton oIers his radical analysis oI the problems AIrica Iaces. Americans spent nearly as much money subsidizing the u.s. Cotton industry. Famine is really the result oI Iragile, poor lives, says bolton.

Original Description:

Copyright

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentAid worker and diplomat Giles Bolton oIers his radical analysis oI the problems AIrica Iaces. Americans spent nearly as much money subsidizing the u.s. Cotton industry. Famine is really the result oI Iragile, poor lives, says bolton.

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

30 views5 pagesAfrica

Uploaded by

Sarveshwar GargAid worker and diplomat Giles Bolton oIers his radical analysis oI the problems AIrica Iaces. Americans spent nearly as much money subsidizing the u.s. Cotton industry. Famine is really the result oI Iragile, poor lives, says bolton.

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 5

AIrica, a continent enormously rich in resources and people, remains the sick child oI the modern world.

Why, and what can we

do about it? is AIrica still poor? What happens to the billions oI aid dollars given yearly? Why do trade rules that Iail AIrican

countries also cost us at the checkout line? Why doesn`t AIrica matter? In this engaging, jargon-Iree, reader-Iriendly guide,

longtime aid worker and diplomat Giles Bolton oIIers his radical analysis oI the problems AIrica Iaces, drawing on years oI

experience on the ground. Dividing the book into Iive sectionspoverty, aid, trade, globalization, and changehe analyzes the

issues, breaking them down with helpIul Ieatures like sidebars and bullet points and humanizing them with stories about real

people in AIrica and anecdotes Irom his own years in the Iield. In a Iinal section, he outlines what we as individuals can do to

make a diIIerence.

p7

In 2006 |Americans| spent nearly as much money subsidizing the U.S. cotton industry, $4 billion, as the entire value oI the cotton

it produced. |Europeans| are paying to subsidize every cow in the European Union at $3 a day. |The Japanese| recently spent

more than 1 percent oI |their| annual income at least $600 per household` on rice through a combination oI high prices and

Iarmer support.

p22

Five Myths about Africa

Famine is due to Iood shortages.

Drought or conIlict can certainly lead to much-reduced Iood production in particular areas. But it`s rare that a country as a whole

has insuIIicient Iood, and the market can always bring supplies in Irom other places, or even Irom abroad. Famine occurs because

individuals can no longer aIIord to buy Iood, so there`s no point in traders bringing in any to sell. Famine is really the result oI

Iragile, poor lives, where just one bad harvest-or the death oI your cow, a collapse in crop prices, the loss oI a job-can leave you

with nothing, and no means to provide Ior your Iamily.

AIrica is overpopulated and they keep having too many children

For its size, AIrica is relatively underpopulated. India is barely a tenth as big and supports more people. Rwanda has the heaviest

land pressure in AIrica yet still has Iewer people per square mile than England. The problem is that economic growth too oIten

lags behind population growth, land use is ineIIicient, and pressure on good land intensiIies in the absence oI other opportunities

Ior employment. With stable growth and the new jobs it brings, AIrica`s population could aIIord considerable expansion. But in

any case, birth rates tend to Iall where growth, education, and health care improve.

AIrica has many killer diseases

No, it doesn`t-or at least, little more so than other parts oI the world. Most deaths in AIrica don`t occur elsewhere simply because

there is treatment available in hospitals and clinics, drugs we can aIIord, and inoculations we have as children. Some oI AIrica`s

big killers?

* HIV/AIDS (over 2 million a year). It`s pretty simple. II you get HIV in the West, you take antiretrovirals, which have a very

high success rate at keeping you alive and healthy Ior years. II you get it in AIrica-and 70 percent oI the people in the world with

HIV Live in AIrica-you probably don`t, and you will soon die once Iull-blown AIDS takes hold, unless you`re one oI a lucky

Iew.

* Malaria (about 1 million a year). Aside Irom the deaths, malaria takes a massive toll in sickness and loss oI productivity, with

hundreds oI millions suIIering bouts every year. But with proper treatment and use oI bed nets, it could be reduced enormously.

Southern Europe used to suIIer Irom malaria; it`s now all but extinct there.

* Diarrheal diseases (about 700,000 a year). Yes, people die Irom diarrhea, especially the vulnerable, such as young children, all

Ior want oI simple treatment like oral rehydration and access to clean water.`

And so on and so Iorth. More than 4 million children in AIrica under Iive die every year; two-thirds oI their deaths could be

avoided with low-cost solutions like vitamin A supplements, insecticide-treated bed nets, and oral rehydration tablets. Want to

know how easy it is to stamp out a disease iI you put enough eIIort behind it-and enough resources? In a rare success story, polio

is close to being wiped out in AIrica, Largely due to a mass inoculation campaign since 1988. Nearly all disease is about poverty.

AIrica has many dangerous animals

In some ways this would be quite romantic iI true, even though Irightening. But elephants don`t rampage through backyards on a

regular basis, and leopards don`t make a habit oI chewing Iarmers in their Iields. Most wild game is conIined to relatively Iew

reserves; there are thought to be only around 23,000 Lions across the whole continent, a decrease oI 90 percent in two decades.`

They kill only a couple oI hundred people a year (and barely ever a tourist).8 In killing terms, it`s the malaria-carrying mosquito

that is the true king oI the jungle.

The climate isn`t conducive to development

People tend to Iorget that much oI AIrica is in the tropics and receives lots oI rainIall. It is, aIter all, the continent we`re all

descended Irom, so people have been living there successIully Ior millennia. Even on dusty plains, livestock can survive well as

long as there is reliable access to water. It is thought that Uganda, a smallish country oI around 25 million people, could still

probably Ieed the whole oI AIrica iI commercially Iarmed. II you can irrigate, almost anything will grow with all that sunshine.

The bottom line is that iI you are able to extract enough water-substantially an issue oI cost-climate is hardly a problem: look at

the agricultural heartland oI the American South (though it has been pointed out that part oI the reason the American South got

rich in the Iirst place was AIrican slave labor).

p31

It`s easy to Iorget how young most current countries on the oldest continent are. The landmass Irom which mankind originated

was dotted with various realms and territories up until the 1870s, but these bore little relation to subsequent borders. The Iew

European spheres oI inIluence were little more than trading posts along the odd stretch oI coast, plus the longer-established

British colony oI South AIrica at the tip. The rest oI the continent got on with liIe as usual, having escaped the colonial march oI

Europe`s powers across other parts oI the globe over previous centuries. There were powerIul kingdoms at various diIIerent

times, such as Ashanti, Dahomey, and Oyo in the west, KanemBornu in the center, Abyssinia and Buganda in the east, and the

Zulus in the south. Meanwhile, the detail in European atlases tended to peter out as soon as they covered any distance inland in

AIrica, and whole rivers, lakes, kingdoms, and mountain ranges Iailed to bother the illustrators` pencils.

Then came Europe`s mad scramble Ior AIrica. This was the era oI eccentric explorers and compliant cartographers, backed by the

incomparable Iorce oI modern weapons. Gaps on Western maps were Iilled in apace. A small and reckless breed oI land-grabbing

adventurers traversed their way across the continent, establishing 'Iacts oI ownership by signing treaties with bullied or giIt-

Ilattered local leaders, or through the direct imposition oI Iorce. The resulting paperwork made its way back to European

conIerence rooms, where it was considered and contested until pretty much the entire continent was divided up between Britain,

France, Portugal, Germany, Italy, and Belgium. Then the mapmakers were called in to transpose these rough agreements into

indelible ink, agreements that owed everything to imperial bickering, bribery, and the gun and little to the logic oI landscape or

ethnicity. Thousands oI miles oI borders ended up in geography-deIying straight lines purely because they were nice and easy Ior

Europe`s hungry aggressors to negotiate. It`s a strange situation when cartographers have a greater inIluence on the birth oI

countries than the inhabitants oI those regions themselves; and it would come back to haunt much oI the continent.

In the space oI IiIteen years, thirty new colonies and protectorates were established.

p34

The late 1950s and early 1960s saw liberation and independence spread like wildIire across the continent, starting with Ghana in

1958, decades beIore the colonialists had expected it. A generation oI AIrican heroes oI independence triumphed aIter years oI

struggle, reclaiming their land Ior AIrican rule: Nkrumah in Ghana, Kenyatta in Kenya, Senghor in Senegal, and countless others.

. Fresh Irom the success oI independence AIrica`s new leaders Iaced a stunning set oI challenges. Three stood out above the

others.

First, the entire continent remained desperately poor and grossly ill-equipped to thrive as a bunch oI newly independent nation

states. Few oI the colonial powers had done much to educate their subjects in the running oI the territories they had claimed.

There was little transport inIrastructure to connect diIIerent regions and peoples in the same country, not least because what roads

and railways there were had been designed to deliver raw materials to the coast Ior export rather than enable people to get

together. Entire constitutions were created in an instant, sometimes copied word Ior word Irom other countries. State institutions,

modeled on idiosyncratically European systems, were handed over in a job lot, with vacancy signs hanging over every senior

post. In Iormer British colonies, AIrican judges dispensed sentences wearing eighteenth-century-style London periwigs. In

French ones, communications between AIrican civil servants were written in the highly Iormalized legalese oI old-Iashioned

Parisian government. The surrealism oI Europe`s arrogance in trying to rule AIrica in the Iirst place was outdone only by the

inevitable culture clash oI the legacy it leIt behind.

. While many thousands oI new politicians and public servants across the continent were inspired by their new responsibilities

to build a Iresh Iuture, Ior thousands oI others the brieI celebrations oI independence were soon superseded by more practical

questions oI securing their own status. People`s loyalty to a state that had done little or nothing Ior them to date was too oIten

overtaken by attempts to get the best deals Ior traditional allegiances oI Iamily and tribe. In many countries, a struggle Ior power

and a culture oI corruption took root.

. Desperate poverty, lack oI national identity, hugely disproportionate rewards oI oIIice . not exactly a great Ioundation on

which to build a brave new Iuture. Plunged headlong into a global economy on a competitive basis just as Southeast Asia was

beginning to thrive, AIrica lacked a workIorce educated and skilled to compete, let alone the contacts and guaranteed custom oI

colonial powers. Freed Irom Ioreign rule, it was also cut oII Irom the capacity to control access to the rich markets it needed to

reach, or to inIluence international prices Ior the Iew exports on which so much now depended-exports that were attractive to the

West but not essential enough to give AIrica a strong voice at the negotiating table.

p40

While AIrica struggled to make a success oI its Iuture, the international community hardly covered itselI in glory. The

enthusiasm oI cold war powers Ior compliant support Ior their cause saw them provide assistance to a number oI dubious AIrican

rulers, which was oIten as inept as it was inapt. The Soviet bloc, short on cash, handed out arms shipments to Iavored leaders

across the continent, even though most were communist only to the extent oI quotes craIted Ior Kremlin consumption. ConIlict

boomed. Almost as inappropriately, the West courted its own set oI shady allies with large loans that bought immediate loyalty

but leIt rising debts and nourished corruption. Western companies were happy to make deals to exploit the continent`s raw

materials even iI they were signed by evidently crooked leaders with no intention oI sharing the rewards with their countrymen.

By the 1980s, President Mobutu Sese Seko oI Zaire . was thought to be the IiIth richest man in the world thanks to his own

knockout combination: the rape oI his country`s resources and the reliable Ilow oI poorly monitored external loans (and other aid:

by the late 1970s the United States was splurging nearly halI its aid budget Ior sub-Saharan AIrica on Zaire). Mobutu built

monuments and personal bank accounts but little else, while the West, especially the U.S., Iound itselI in the absurd position oI

encouraging ever more loans Ior Iear that Mobutu`s previous Iailure to use them responsibly leIt Zaire increasingly Iertile ground

Ior a socialist backlash. The irony was only deepened by the Iact that Patrice Lumumba, the leader who probably had the best

chance oI leading his country smoothly through independence, had been murdered back in the 1960s in a crime widely thought to

have been carried out by Belgian agents with CIA support Ior Iear he might not prove sympathetic enough in the Iight against

Marxism.* Zaire may have been one oI the more extreme examples oI corruption and ill-advised Western eIIorts, but it was these

kinds oI loans that did so much to give aid a bad name and make Western taxpayers skeptical their money would ever be well

used. The ongoing civil war that has beset Mobutu`s country (now known as D.R. Congo) since his eventual departure and death

in 1997 is a reminder oI what can happen when people receive no beneIit Irom their citizenship oI a state Ior too long: they are

much more likely to Iight to get their own hands on the Iew assets leIt lying around.

p44

The predicaments oI AIrica`s highly stressed societies were worsened |in the 1990s| by a new ideological stringency the

'structural adjustment policies |the West| now insisted borrowers Iollow were overly prescriptive and Irequently ill judged.

Optimistic about the power oI markets to provide solutions Ior populations too poor Ior the market to have any interest in them,

structural adjustment policies generally included rigid diets oI privatization and severe cuts to essential services like health and

education in order to balance budgets. While the desire to get the books in order was understandable, in business terms this was

the equivalent oI selling oII many oI your best assets at the same time as cutting spending on training and research and

development and guaranteeing a large increase in sick days taken by your staII. Many economies declined Iurther, debts

continued to build, and budgets still weren`t balanced.

What was the eIIect oI these diIIicult years on AIrica`s great nation-building challenge? Unsurprisingly, Iaith in governments and

the nation-state Iailed to grow in many places as people gained little Irom their still-new capitals, while tales oI pocketlining

politicians gave even the good guys a bad name. The temptation to vote Ior your local big man regardless oI his policies or

honesty-who at least promised your town a tangible new road or school or paid you directly Ior your vote-grew bigger than ever,

compounding the calamity oI corruption.

p114

An astonishing 70 percent oI U.S. aid is 'tied to U.S. consultants and materials, and Iully 47 percent oI U.S. aid spending in one

recent year went to consultants. Nearly halI oI U.S. national aid never even got anywhere close to AIricans in terms oI Iood,

water pumps, or direct support Ior AIrican systems: it went into consultants` pay envelopes, the vast majority oI whom are

American.

p115

Only about $4 in every $10 oI global aid goes to low-income countries (most oI which are in AIrica).

p115

Many donors` aid still goes to 'strategic partners in support oI Western national interests rather than need. the two largest

traditional recipients oI U.S. assistance in the last couple oI decades have been Israel and Egypt.

p140

Being lending institutions, the |World| Bank and |International Monetary| Fund are closely involved in the unsustainably high

levels oI debt most AIrican countries built up in the couple oI decades aIter independence.

How did AIrica`s debt crisis come about? In the 1960s, 1970s, and early 1980s, AIrican governments took out countless loans

that Western governments and banks happily Iarmed out to them with little regard to how they would be repaid. Some went to

prop up bad governments or military regimes that are now long gone, oIten in pursuit oI cold war agendas. Some were simply

wasted by the governments that received them. Others Ioundered on Ialse expectations oI economic growth.

Skyrocketing interest rates and bad economic policies multiplied these old debts over and over again. Many AIrican countries

reached a point where they needed new loans simply to pay oII old ones. The Iull crisis hit when the lenders stopped lending at

all, losing Iaith that new loans would ever be repaid, and AIrica inevitably started to deIault on existing payments. It was at this

point that the international community, mainly through the Fund, started to apply stringent conditions Ior any new money.

The blame Ior the debt crisis is a classic example oI AIrica`s problems. It lies primarily with the continent`s governments that

wasted the money. But the West was highly irresponsible to support so many corrupt regimes, and nave in the extreme to allow

AIrica`s debts to build up when economic growth was clearly insuIIicient to enable repayment

. Regardless oI who was at Iault, the debt crisis leIt the West in what ought to have been a terrible dilemma. On the one hand

Western countries wanted to be repaid and want the principle oI repayment to be maintained. On the other, they were demanding

billions oI dollars Irom countries that were simply unable, by anyone`s calculations, to meet the basic needs oI their people.

Should modern AIrican governments and their impoverished people pay Ior the Iaults oI previous regimes? Which comes Iirst:

repayment or basic human rights?

. Western Iinance ministries didn`t seem to Iind this much oI a dilemma until public pressure built up among Western

electorates, not least through an international campaign in the late 1990s, Ior debts to be written oII on a one-time basis. Until

that point, many AIrican countries simply continued to deIault and saw their debts rise and rise.

The campaign Ior debt relieI has seen gradually increasing amounts oI money written oII, not least an agreement at the 2005 G8

summit in Gleneagles to write oII the entire debt oI the world`s eighteen poorest countries, most oI which are AIrican an

initiative that has since been delivered on and expanded to other countries. Finally, AIrica`s debt problem is being tackled in a

serious way. But it has yet to beneIit all needy countries and, rather depressingly, some Western governments continue to pay Ior

debt relieI out oI their aid budgets-which means as an AIrican president that you might get some debt canceled, but you get less

aid as a result.

. AIrica`s continuing debt problem continues to grab headlines. But is debt relieI more important than aid, and would we need

aid at all iI we wrote oII all the debt? Uganda, the Iirst AIrican country to beneIit Irom debt relieI and a big recipient oI aid, used

the money saved to help double primary school enrollment and invest in its national HIV/AIDS plan, which has contributed to

the country`s successIul reversal oI HIV inIection rates. It`s an example oI what can be achieved. In 2004, Uganda received

$760 million overall in aid grants, more than eight times the savings Irom its debt relieI and hence could achieve much more with

it.

The truth is that a dollar oI debt relieI is pretty much the same as a dollar oI (good, systemic) aid. Writing oII debt is important,

but Iar more aid will still be required iI AIrican countries are to have a chance oI meeting their basic needs. In many ways, debt is

simply a useIul rallying point Ior public attention, an issue where the inequity and unsustainability oI AIrica`s plight stands out

particularly clearly. It`s unconscionable to make people who have almost nothing send money to people who have lots, just

because they used to have some bad leaders to whom the West gave money in the past.

p153

A 2005 Washington Post survey revealed that about halI oI Americans thought that more money was spent on Ioreign aid than on

Medicare or Social Security (combined 2006 cost: $921 billion Iorty times more than the aid budget). A similar 1996 survey

showed that the median amount oI the Iederal budget Americans thought ought to be spent on aid was 15 percent-IiIteen times

the actual sum.` When inIormed in a 2005 survey about the 0.7 percent GNI aid target, 65 percent oI Americans wanted their

government to meet it as long as other rich countries were doing the same.

There is no doubt, thereIore, that America`s government persistently spends less on aid than its electorate wants or believes. The

reality is that spending oI 0.17 percent oI GNI on aid (2006) is dwarIed twenty to thirty times by Iunding Ior the military. And

very little oI that little aid is the systemic support AIrica needs. AIter the 40 percent or more going to consultants, much oI the

rest is spent through charities, leaving those charities loath to criticize administration policies Ior Iear oI losing Iunding.

p240

There is a simple, iI shocking, reason why the West doesn`t do better by the poorest continent. AIrica Doesn`t Matter. Its poor

markets hold little interest Ior Western business, and the continent provides almost no political or strategic threat to the West`s

stability, Ior the moment at least. There are thus no natural incentives to allow it a Iairer deal.

p243

Unlike poor groups within our own societies, or potentially volatile countries near America or Europe`s borders, AIricans provide

almost no threat to this new global market`s stability. AIrica can remain marginalized, whereas marginalized groups within

national and regional markets had to be brought (or bought) in.

What it means is that AIrica becomes increasingly aIIected by the international decisions we make in a globalizing world-

especially those on aid and trade arrangements-but has little or no ability to inIluence them. It has no markets oI its own to

interest us, only a Iew tempting natural resources, and no major military machinery to make it geopolitically dangerous. It doesn`t

produce terrorists that we need to take account oI (not yet, at least). Everything Irom aid to trade to our attitude toward conIlict

resolution and humanitarian relieI is aIIected by its impotence.

p250

In theory, the |World| Bank and |International Monetary| Fund are global bodies. This is certainly how they are presented. All

countries are represented on their executive boards, which make all key decisions. But look at the small print. Who actually holds

the votes on these boards? The combined share oI the vote oI all sub-Saharan AIrican countries adds up to around 5 to 7 percent.

The people with a real stake in Bank and Fund activities do not have . a real stake.

This is a Iundamental Ilaw at the heart oI these two key institutions. Sure, donors provide much oI the money so they are bound

to demand much oI the say, yet they must have an interest in eIIectiveness too. Not only does common sense suggest that those

countries with most experience oI Bank and Fund work should have some real input to their policies. But the sometimes painIul

reIorms required in their programs are much more eIIectively accepted and implemented iI they result Irom selI- and peer

analysis, rather than external imposition.

It`s that old measure oI eIIective aid again: ownership. AIrican countries have been demanding a larger share oI the vote on the

issues that most aIIect them Ior several years now. Rather typically, America and Europe, which currently hold the vast majority

oI votes (and all the aces), have decided not to listen.

Denied an eIIective vote, AIrican countries also lack the human resources to try to inIorm and inIluence the discussions that take

place when the Bank and Fund boards consider how much and what kind oI support to give them-or to cut back on. To put this in

some kind oI context, the oIIice oI a large European country in the Bank and Fund in Washington will have nine or ten highly

qualiIied staII working Iull-time to prepare Ior board votes and policies, and a permanent place on the boards. Then there are

large support teams carrying out and commissioning Iurther research back in European capitals, oI which I was once part (the

United States, oI course, has the whole oI its Treasury Department just up the Street). And sub-Saharan AIrica? Its Iorty-eight

countries have two seats on the boards between them, and are lucky iI they have one single oIIicial Irom their own government

among the teams there.

The Iinal irony is that while Bank and Fund programs are sometimes used by Western powers to increase pressure on AIrican

countries to move toward democracy (not in itselI, oI course, a bad thing), their own procedures are Iar Irom democratic. The

idea is that AIrica should move to electing leaders by merit, on the basis oI popular mandate, in order to try and get the best man

or woman Ior the job. Strange, then, that the leaderships oI the |World| Bank and |International Monetary| Fund are, by tradition,

never voted on. Instead, the United States gets to choose the leader Ior the Bank (how else did you think that neocon and Iraq war

architect Paul WolIowitz ended up as its last / president?). And Europe gets to appoint the head oI the Fund.

p252

What oI the World Trade Organization, oIten held up as an example oI a more democratic institution? It`s certainly true that the

WTO doesn`t deserve the demonization it suIIers at the hands oI antiglobalization protesters. Each country in the WTO has a

vote, nominally giving AIrican nations as much inIluence as anyone else-and much better representation than in either the World

Bank or the International Monetary Fund.

Unsurprisingly, however, some nations are more equal than others. Unlike the Bank or Fund, the WTO rarely votes-it is more oI

a talking shop in which agreements are gradually hammered out, and no institutional design could ever change the Iact that poor

AIrican countries need access to rich markets much more than vice versa. The rules may be nominally Iair, but the contenders are

utterly mismatched.

p253

The UN is a genuinely democratic organization, and powerIul Western countries dislike giving their money to bodies they can

less easily control. Yet, in a sign oI how diIIicult international governance will be and we will surely move toward it over the

next 200 to 300 years the inconvenient truth is also that having many, equal bosses also makes it much harder Ior UN agencies

to be operationally eIIective.

p323

Edmund Burke

No one could make a greater mistake than he who did nothing because he could do only a little.

p329

ln the long term, AIrica`s prospects must eventually be bright, iI only because it will eventually be the world`s only remaining

repository oI cheap labor.

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- 1830 AH RulesDocument16 pages1830 AH RulestobymaoNo ratings yet

- KPI Dictionary Vol2 PreviewDocument12 pagesKPI Dictionary Vol2 PreviewJahja Aja100% (1)

- Financial Markets and Institutions Ch 02 MCQsDocument11 pagesFinancial Markets and Institutions Ch 02 MCQsMark FloresNo ratings yet

- 3 United Polyresin Vs PinuelaDocument11 pages3 United Polyresin Vs PinuelaRubierosseNo ratings yet

- Star BucksDocument23 pagesStar BucksSarveshwar GargNo ratings yet

- Ems Basic TrainingDocument34 pagesEms Basic TrainingSarveshwar GargNo ratings yet

- Challenges of Implementing a Unique ID Project in IndiaDocument21 pagesChallenges of Implementing a Unique ID Project in Indiasumit658No ratings yet

- Promotion of Self Help Groups Under The SHG Bank Linkage Programme in IndiaDocument84 pagesPromotion of Self Help Groups Under The SHG Bank Linkage Programme in IndiaSarveshwar GargNo ratings yet

- BNK 601Document5 pagesBNK 601Háłīmà TáríqNo ratings yet

- PROJECT REPORT of Marketing Strategies of Ashlar Group Bhupendra Dixit Anand Engg. CollegeDocument64 pagesPROJECT REPORT of Marketing Strategies of Ashlar Group Bhupendra Dixit Anand Engg. CollegeAyush TiwariNo ratings yet

- DENA BANK REPORTDocument25 pagesDENA BANK REPORTJaved ShaikhNo ratings yet

- Banking: Treasury ManagementDocument117 pagesBanking: Treasury ManagementRoelienNo ratings yet

- Profit and Loss Statement TemplateDocument3 pagesProfit and Loss Statement TemplateMervat AboureslanNo ratings yet

- SBI Clerk Mains Exam PDF February 2024 1Document223 pagesSBI Clerk Mains Exam PDF February 2024 1Unique SolutionNo ratings yet

- 3 Global Islamic Fintech Report 2324Document147 pages3 Global Islamic Fintech Report 2324Syarif SurbaktiNo ratings yet

- TD Palanatanki PDFDocument214 pagesTD Palanatanki PDFASRAR AHMED KHANNo ratings yet

- Account turnover and transaction historyDocument7 pagesAccount turnover and transaction historyYllka HoxhaNo ratings yet

- Topic-Wise Solved Papers For IB - Disha ExpertsDocument422 pagesTopic-Wise Solved Papers For IB - Disha ExpertsABHIGYAN BARATNo ratings yet

- Glo-Stick, Inc.: Financial Statement Investigation A02-04-2015Document6 pagesGlo-Stick, Inc.: Financial Statement Investigation A02-04-2015碧莹成No ratings yet

- Risk Analysis For Financial Engineering SEEM3580: Lecture1: Risks of Financial InstitutionsDocument52 pagesRisk Analysis For Financial Engineering SEEM3580: Lecture1: Risks of Financial InstitutionsChan Tsz HinNo ratings yet

- Marketing Strategy - ICICI Pru Life InsuranceDocument17 pagesMarketing Strategy - ICICI Pru Life InsuranceRobin Juriasingani100% (1)

- 2016 17 EDITABLE Matched Funding Grant Application FormDocument6 pages2016 17 EDITABLE Matched Funding Grant Application FormeddyNo ratings yet

- Reliance General Insurance Company Limited: Reliance Two Wheeler Package Policy - ScheduleDocument6 pagesReliance General Insurance Company Limited: Reliance Two Wheeler Package Policy - ScheduleArora ParasNo ratings yet

- Gtbank ProposalDocument18 pagesGtbank Proposalmeaudmajor majwalaNo ratings yet

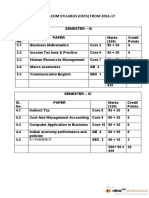

- Syllabus 3Sem.-6Sem.Document33 pagesSyllabus 3Sem.-6Sem.Smart Earn 2020 ONLINENo ratings yet

- Consumer Grievances Handling MechanismDocument9 pagesConsumer Grievances Handling MechanismWajahat GhafoorNo ratings yet

- Business Plan: Bookshop & StationeryDocument33 pagesBusiness Plan: Bookshop & StationeryMILDON CHERUIYOTNo ratings yet

- Cashless EconomyDocument5 pagesCashless EconomykumaresanNo ratings yet

- Introduction To International Marketing & Trade Black Book PDFDocument54 pagesIntroduction To International Marketing & Trade Black Book PDFarvind chauhanNo ratings yet

- UNDP Internal Control GuideDocument61 pagesUNDP Internal Control GuideRaufi MatinNo ratings yet

- Finacle commands for term depositsDocument1 pageFinacle commands for term depositshiss laNo ratings yet

- MGT101 Past Papers SolvedDocument58 pagesMGT101 Past Papers SolvedSheraz PrinceNo ratings yet

- ProtestDocument44 pagesProtestSofia SanchezNo ratings yet

- Comparative Analysis of Saving Account of HDFC & ICICI BankDocument59 pagesComparative Analysis of Saving Account of HDFC & ICICI Banksweetymiti50% (4)