Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Hist of Theatre Movement

Uploaded by

Adithya NarayanOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Hist of Theatre Movement

Uploaded by

Adithya NarayanCopyright:

Available Formats

THE HISTORY OF THE THEATRE MOVEMENT IN KERALA A FEMINIST READING

It is most vital to have a knowledge of the living conditions of the Malayalee women during the period of genesis of theatre in Kerala, for without it, the history of the feminist theatre movement would be deemed incomplete. In those days, did Malayalee women get an opportunity to come to the forefront of the public domain as a writer, director as actor? Was she bold enough to unchain her body and mind for such a theatrical performance? Several socioeconomic factors related to the Malayalee women at the fag end of the nineteenth century, including her body language, manner of dressing and education, play a crucial role in deciding her involvement in the theatre. The outstanding factor that captures the attention of anyone who analyses the state of women in Kerala during the nineteenth century, is the fact that the most rigid rules of aristocracy were dependent for women. There were several unwritten rules regarding the code of conduct of women belonging to different castes of the society. Some of them including a woman not being supposed to be seen by any other man except her husband, not expected to let her hair loose etc., were as stringent as those imposed during the menstrual period.1 Caste was the crucial factor in deciding the dress code of women in society. An Ezhava woman was not allowed to wear a mundu which reached below here knees while a Nair woman was permitted to wear a mundu (Achipudava) that went below her knees. None of the Hindu women, except

2 Antharjanams who travelled outside in Khosha, were allowed to cover the upper part of the body above the waist. History has recorded the great revolt that erupted when certain converted Channar women of Southern Travancore attempted to cover the upper part of their body.2 The author of Kochi Rajyacharitram has remarked that it is indeed shameful for Maharaja Ramavarma to have issued a proclamation demanding that Nair women should remove their blouses in order to enter temples, at the outset of the twentieth century, when it was widely perceived to be disgraceful for women to travel outside without covering their bosom.3 There are several instances of women who dared to break these laws beings subjugated to severe torture. The upper castes were so outraged by a Channar Womans daring act of walking through the streets of Kayamkulam with a piece of cloth covering her bosom that they forcibly removed it and attached a tender coconut fruit to her nipples.4 A commotion is said to have erupted when a group of Nair men forced an Ezhava woman to remove her mundu for having dared to wear it, reaching below her knees.5 C. Kesavan reminisces regarding the events following the Travancore Diwan, Sir T. Madhavarayars order prohibiting the lower caste womens attempts to imitate the upper caste womens right of covering their bosom. These included the challenging of this order by the Madras Governor Sir Charles Treveleyan and the subsequent developments thus: The gist of it was that the mighty British empire was ruled by a woman who would never pardon the insult heaped upon the womanhood of her sisters,

3 a fact to be borne in mind by the ruler of Travancore. A threat was also raised that if the need arose the problem would be resolved with the bayonet subsequently a proclamation was issued granting freedom to wear any dress to anyone As a mark of celebration of the freedom of women, one of my maternal ancestors even distributed dhotis among Ezhava women to cover their bosom.6 The use of blouse to cover the breasts was frowned upon still further as blouse was considered alien to the culture of Kerala and looked upon as a symbol of religious conversion. The act of wearing blouse was considered as a sign of haughtiness and a part of dressing up. In his autobiography Jeevithasamaram, C. Kesavan has narrated how his mother was scolded by her mother-in-law when she wore a blouse for the first time. It also mirrors the contempt for female artists. Where the hell are you going capering?7 . . . Remove it . . . You voluptuous dancer, dressed like a non-Hindu woman in a blouse.8 The underlying suggestion evidently remains that singing and dancing were all the hereditary occupation of prostitutes. Malayalam Theatre took

shape in a social environment where the identity of a dancer was deemed unfit for women belonging to aristocratic families. The Kerala society of those times placed severe constrains on the Malayalee womans manner of dressing, behaviour and the public space where she could freely move about, which forced her to seek solace in folk and classical art forms to express herself. But as a part of the new identity which she seemed to have acquired towards the end of the nineteenth century, the Kerala woman seemed to be losing out even on these. It was not substituted with the new stage arts. There were numerous

4 women who were exceptionally gifted in language, literature and the Puranas but none of them were educated in the present day sense. In his article entitled The most important Incident of my Life.9 C.V.Kunjiraman speaks of a young, scholarly lady who taught him to read and explain the meaning of the Ramayana ,four or five years before he turned fifteen, praising her expertise to render verses of the epic in different ragas. He also dwells at length on the skill of a great aunt of his, born at the beginning of the nineteenth century, to read and write. . . . There is a widespread misconception that school education commenced only recently, especially with regard to Ezhava women. My great aunt was a real exception who, as long as her eye-sight was sound, used to read the Ramayana late into the evening as long as there was sufficient light.9. The social identity of women at the time when the theatre was taking shape in Kerala encompassed all the above cited complexities. Therefore

there were several conditions that were both conducive and non-conducive for women to become a part of the staging and acting of plays in those days which are to be borne in mind while analyzing the early stages of the womens

theatre movement. Early plays by women It was in 1890 that Angjathavasam10, a play dealing with the Pandavas anonymous stay depicted in the Mahabharata, came out in Malayalam. Modelled after Sanskrit plays, it was written by Thankachi, the first woman playwright in Malayalam. . . as per records. Observers commented that the play was confined just to be read and enjoyed by the literati, yet there were

5 certain gems hidden here and there in a work that was not altogether bad. 11 Despite being equally known as the others dramatists of the period, her work has never found a place in the annals of the theatre history of Kerala. Another lady who wrote a drama after Kuttikunju Thankachis Angjathavasam was Thottakkattu Ikkavamma, the author of Subhadrarjunam. Subhadrarjunam surely deserves a place of pride among the independent language plays of the period. The Lords of Kodungalloor, who were great poets, alone had written such plays till then. Kuttikunju Thankachis Angjathavasam was the sole exception to this. Subhadrarjunam, published

towards the end of 1891, was the second play written by a woman.12 Ikkavamma had firm faith that women had the same right and were as capable as men to entertain and engage the attentions of the literati. When a false rumour spread that her works were written by Mannadiar, Vidya Vinodini of those times mentioned that she deserves to be called the

Thunchathezhuthachan of the female sex.13

It will be impossible for any

reader of Subhadrarjunam to claim that she has no knowledge of the theatrical art. The scattered observations regarding stage directions and acting found in the play bear testimony to a very mature dramatic composition. The famous scholar Karamana Keshava Shastrikal had translated this play into Sanskrit at that period itself. The plays popularity is evident from the way in which it was written about and discussed in the newspapers and periodicals of those days. Thottakkattu Ikkavamma was much influenced by the transformations taking place in the theatre at that time and was more involved with all these, than was possible for a woman of that period.

6 At around this time Kerala was gradually getting acquainted with Tamil Musical plays. Simultaneously C. Achutamenon composed Sangeeta-

Naishadham, thirty four thousand copies of which were sold in 1892 itself, the year of publication of the play. He undertook the composition of the play under the active encouragement of his maternal sister Ikkavamma. Ikkavamma of Thrissur Ramanchira Madham happened to watch Kerala Varma Valiya Koyi Thampurans play Abhingjana Sakuntalam staged by Manomohanam company and invited them over to Thrissur. This presentation was greatly influenced by Tamil drama and had little musical merit in it. Her wish expressed to her

nephew that a play free from the effect of Tamil Theatre should be created, sowed the seeds for Naishadham.14 Apart from composing the play, Achutamenon also demonstrated his histrionics by playing the part of the forest-dweller. When the play was staged in Thrissur in 1892, Ikkavamma played the role of Nala and Ambadi Govinda Menon acted as Damayanti.15 This account will suffice to prove that Ikkavamma was not only one of the earliest women to have mastered play righting but also stage activities in the true spirit. On the basis of the

information available, she remains the first woman to have acted in a Malayalam drama. Why did she not don the role of a woman? Did she

deliberately choose the guise of man to conceal her womanhood from the society? From Ikkavamma, the lady who concealed her identity behind the mask of a man, the theatrical history of Kerala marched forward to the world of musical drama where male actors donned the role of women. Thus the advent

7 of women added a new chapter to the stage language of musical drama in Malayalam which forms a major phase in the history of the theatre in Kerala. * * * * * * * * *

1. Bhaskaranunni. P, Pathombatham Noottandile Keralam. Kerala Sahitya Academy, Thrissur, 1988. 2. Ibid. 3. Padmanabha Menon, K.P., Kochi Rajyacharitram. 4. Bhaskaranunni. P., Pathombatham Noottandile Keralam. Kerala Sahitya Academy, Thrissur, 1988. 5. Arattupuzha Velayudha Panickker, P.O.Kunjupanikker, S.N.D.P. Yogam, Kanakajubilee Smaraka Grantham, 1953. 6. Ibid. 7. Ibid. 8. Ibid. 9. Puthuppalli Raghavan (Ed.) C.V.Kunjuramante Thiranjedutha Krithikal, Kaumudi Public Relations, Thiruvananthapuram, 2002. 10. Bhaskaran Nair, V., (Ed) Kuttikunju Thankachiyude Kritikal (1979), Kerala Sahitya Academy, Thrissur. 11. Ulloor S. Parameswara Iyer, Kerala Sahityacharitram Vol.4 (1974) Kerala University Publications Department, (1974), 273. 12. Ulloor S. Parameswara Iyer, Kerala Sahitya Charitram Vol.4 (1974) Kerala University Publications Department, 681. 13. Thottakkattu Ikkavamma, Subhadrarjunam (1891). Prof. P. Sankaran Nambiar Foundation, Thrissur, 2002.

8 14. Ulloor S. Parameswara Iyer, Kerala Sahitya Charitram, Vol.4 (1974), Kerala University Publications Department, 497. 15. Madavoor Bhasi, Malayala Nadaka Sarwaswam (1990). Chaitanya Publications, Vattiyoorkkavu, Thiruvananthapuram. *****

You might also like

- Feminist Writing in Malayalam Literature A Historical PerspectiveDocument31 pagesFeminist Writing in Malayalam Literature A Historical PerspectiveSreelakshmi RNo ratings yet

- 1803Document8 pages1803Hardik DasNo ratings yet

- Historical Perspectives and Role of Women in Tamil LiteratureDocument9 pagesHistorical Perspectives and Role of Women in Tamil Literatureshakesbala100% (1)

- ProjectDocument24 pagesProjectSalmanNo ratings yet

- Army Institute of Law: Project On Life of KalidasDocument7 pagesArmy Institute of Law: Project On Life of KalidasManish KumarNo ratings yet

- Ponniyin Selvan - The Supreme Sacrifice Part 5From EverandPonniyin Selvan - The Supreme Sacrifice Part 5Rating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (7)

- Women in Urdu Literature - تنقیدDocument8 pagesWomen in Urdu Literature - تنقیدumayrh@gmail.comNo ratings yet

- Malayalam DramaDocument12 pagesMalayalam DramatharupathihtrealtyNo ratings yet

- Ramayana Book ReviewDocument8 pagesRamayana Book Reviewapi-280769193No ratings yet

- Chola SourcesDocument5 pagesChola SourcesRaheet KumarNo ratings yet

- Asian Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies: Available Online at Volume 2, Issue 2, February 2014 ISSN: 2321-8819Document4 pagesAsian Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies: Available Online at Volume 2, Issue 2, February 2014 ISSN: 2321-8819patel_musicmsncomNo ratings yet

- 4.classical Sanskrit Literature (1209)Document3 pages4.classical Sanskrit Literature (1209)Naba ChandraNo ratings yet

- "An Introduction" and "The Old Playhouse": Kamala Das' New Trials of Emancipation For Indian WomenDocument10 pages"An Introduction" and "The Old Playhouse": Kamala Das' New Trials of Emancipation For Indian WomenTJPRC PublicationsNo ratings yet

- Female Authorship in IranDocument17 pagesFemale Authorship in IranMadou JansenNo ratings yet

- Intoduction On Women Writing by ShodhgangaDocument50 pagesIntoduction On Women Writing by ShodhgangashachinegiNo ratings yet

- Champa in River of FireDocument6 pagesChampa in River of FireMahnoor JamilNo ratings yet

- 10 Noti Binodini Moyna Feminist TheatreDocument16 pages10 Noti Binodini Moyna Feminist TheatreemmadenchNo ratings yet

- Chapter XIII CULTURE Karnataka PDFDocument52 pagesChapter XIII CULTURE Karnataka PDFSoma ShekarNo ratings yet

- THECOLAS01Document7 pagesTHECOLAS01Instant DIYsNo ratings yet

- Daughters of Kerala: 25 Short Stories by Award-Winning Authors, Presents ADocument3 pagesDaughters of Kerala: 25 Short Stories by Award-Winning Authors, Presents AMrbin LiveNo ratings yet

- The First Floods - Ponniyin Selvan Part 1From EverandThe First Floods - Ponniyin Selvan Part 1Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (8)

- Ancient History 24 - Daily Notes - (Sankalp (UPSC 2024) )Document15 pagesAncient History 24 - Daily Notes - (Sankalp (UPSC 2024) )nigamkumar2tbNo ratings yet

- Samvit - July 2013Document12 pagesSamvit - July 2013Nithin Kadoor KongadNo ratings yet

- Janavashya of KallarasaDocument3 pagesJanavashya of KallarasaRavi Soni100% (1)

- Kalidasa's Similes In Sangam Tamil Literature: New Clue To Fix His AgeFrom EverandKalidasa's Similes In Sangam Tamil Literature: New Clue To Fix His AgeNo ratings yet

- Blackburn - Inside The Drama-HouseDocument276 pagesBlackburn - Inside The Drama-HousevarnamalaNo ratings yet

- WWW Indianetzone Com 22 Literature - During - Gupta - Age HTMDocument5 pagesWWW Indianetzone Com 22 Literature - During - Gupta - Age HTManiayu12001No ratings yet

- 1442-Article Text-2331-1-10-20220920Document11 pages1442-Article Text-2331-1-10-20220920Lakshmikaandan RNo ratings yet

- A HISTORY OF INDIAN ENGLISH DRAMA - Sunoasis Writers Network PDFDocument10 pagesA HISTORY OF INDIAN ENGLISH DRAMA - Sunoasis Writers Network PDFSovan ChakrabortyNo ratings yet

- The Misssing Male - NotesDocument4 pagesThe Misssing Male - NotesRizwanaNo ratings yet

- A Feminist Analysis of Habba Khatoon'S Poetry: Dr. Mir Rifat NabiDocument7 pagesA Feminist Analysis of Habba Khatoon'S Poetry: Dr. Mir Rifat NabiShabir AhmadNo ratings yet

- Analysis On Sultana's Dream by Begum RokeyaDocument7 pagesAnalysis On Sultana's Dream by Begum RokeyaMahbub HasanNo ratings yet

- Kamala Das - A Devotee of Krishna and A Free SpiritDocument0 pagesKamala Das - A Devotee of Krishna and A Free SpiritBasa SwaminathanNo ratings yet

- 144527203Document243 pages144527203Junaid RatherNo ratings yet

- The Modern Kama Sutra: An Intimate Guide to the Secrets of Erotic PleasureFrom EverandThe Modern Kama Sutra: An Intimate Guide to the Secrets of Erotic PleasureNo ratings yet

- Dont You Know Sita - R ChudamaniDocument18 pagesDont You Know Sita - R ChudamaniPuthaniNo ratings yet

- Indianfeministtheatreaesthetics PDFDocument21 pagesIndianfeministtheatreaesthetics PDFSrishti GuptaNo ratings yet

- Breaking Stones AssignmentDocument8 pagesBreaking Stones AssignmentSarah Belle33% (3)

- Kalidasa AbhijnanashakuntalamDocument24 pagesKalidasa AbhijnanashakuntalamDiki DuarahNo ratings yet

- LIB 1016 Mod 2Document67 pagesLIB 1016 Mod 2KSSK 9250No ratings yet

- Legendary Society of Ancient TamilsDocument187 pagesLegendary Society of Ancient Tamilsdhiva0% (1)

- Presentation of Women in Literature From Past To Present: Tippabhotla VyomakesisriDocument3 pagesPresentation of Women in Literature From Past To Present: Tippabhotla VyomakesisrivirtualvirusNo ratings yet

- 09 - Chapter 5Document20 pages09 - Chapter 5Tinayeshe NgaraNo ratings yet

- 10 Chapter 5Document24 pages10 Chapter 5contrasterNo ratings yet

- Representations of Elite Ottoman WomenDocument42 pagesRepresentations of Elite Ottoman Womendeniz alacaNo ratings yet

- Kalabhras Arun Part 2Document76 pagesKalabhras Arun Part 2Ravi SoniNo ratings yet

- Vikrama Cholan UlaaDocument43 pagesVikrama Cholan Ulaaturun4No ratings yet

- History of Indian DramaDocument4 pagesHistory of Indian DramaDejan JankovicNo ratings yet

- Fullpaper CharithaLiyanageDocument17 pagesFullpaper CharithaLiyanageJunjiNo ratings yet

- Configurations in Ashes: Twentieth Century Indian Women WriteraDocument14 pagesConfigurations in Ashes: Twentieth Century Indian Women WriteraMuskaan KanodiaNo ratings yet

- Introducing VyangyaVyakhyaDocument3 pagesIntroducing VyangyaVyakhyasingingdrumNo ratings yet

- Question Answers UGDocument6 pagesQuestion Answers UGAnonymous v5QjDW2eHxNo ratings yet

- 5.tamil Literature (1222)Document2 pages5.tamil Literature (1222)Naba ChandraNo ratings yet

- Cilappatikaram - WikiDocument55 pagesCilappatikaram - WikiDaliya. XNo ratings yet

- KALIDASADocument10 pagesKALIDASAAparsha100% (1)

- Oldest Indian Erotica in ArtDocument14 pagesOldest Indian Erotica in ArtRAJENDRA PRASAD PANDEY86% (7)

- Additional DocumentsDocument4 pagesAdditional DocumentsAdithya NarayanNo ratings yet

- The Origin of Science With NotesDocument10 pagesThe Origin of Science With NotesAdithya Narayan83% (6)

- Literature To Combat Cultural Chauvinism: Rashmi Dube Bhatnagar & Rajender KaurDocument4 pagesLiterature To Combat Cultural Chauvinism: Rashmi Dube Bhatnagar & Rajender KaurAdithya NarayanNo ratings yet

- PHD Regulations - 2012 - RevisedDocument19 pagesPHD Regulations - 2012 - RevisedAdithya Narayan100% (1)

- Cultural Resonance: Bengali Literature in Malayalam TranslationDocument1 pageCultural Resonance: Bengali Literature in Malayalam TranslationAdithya NarayanNo ratings yet

- New Microsoft Word DocumentDocument1 pageNew Microsoft Word DocumentAdithya NarayanNo ratings yet

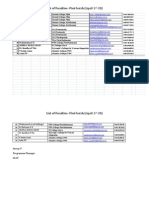

- List of Faculties - First Batch (April 17-20)Document2 pagesList of Faculties - First Batch (April 17-20)Adithya NarayanNo ratings yet

- Cultural ResonanceDocument15 pagesCultural ResonanceAdithya NarayanNo ratings yet

- AryaDocument2 pagesAryaAdithya NarayanNo ratings yet

- The Hero's JourneyDocument257 pagesThe Hero's JourneyAdithya Narayan100% (10)

- Ernest HemingwayDocument20 pagesErnest HemingwayAdithya NarayanNo ratings yet

- International Business in IndiaDocument9 pagesInternational Business in IndiaAdithya NarayanNo ratings yet

- A Room of One's Own: Analysis of Major CharacterDocument6 pagesA Room of One's Own: Analysis of Major CharacterAdithya NarayanNo ratings yet

- Globalization and Contemporary Literature: Nico IsraelDocument5 pagesGlobalization and Contemporary Literature: Nico IsraelAdithya NarayanNo ratings yet

- Additional DocumentsDocument4 pagesAdditional DocumentsAdithya NarayanNo ratings yet

- Textual ScholarshipDocument23 pagesTextual ScholarshipAdithya NarayanNo ratings yet

- Globalization and CultureDocument106 pagesGlobalization and CultureAdithya NarayanNo ratings yet

- Phonetic Disc 1Document2 pagesPhonetic Disc 1Adithya NarayanNo ratings yet

- Globalization and CultureDocument106 pagesGlobalization and CultureAdithya NarayanNo ratings yet

- Globalization and CultureDocument106 pagesGlobalization and CultureAdithya NarayanNo ratings yet

- Women's Studies Syllabus For UGCDocument7 pagesWomen's Studies Syllabus For UGCAdithya NarayanNo ratings yet

- Joseph AndrewsDocument6 pagesJoseph AndrewsAdithya NarayanNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument35 pagesUntitledAdithya NarayanNo ratings yet

- KarnadDocument10 pagesKarnadAdithya NarayanNo ratings yet

- Reading Subaltern Studies: Introduction by David LuddenDocument21 pagesReading Subaltern Studies: Introduction by David LuddenPaul Mathew100% (1)

- 2.2Document5 pages2.2Quân Mynk VũNo ratings yet

- Contemporary Activity No 8Document3 pagesContemporary Activity No 8John Mark Ranilo100% (1)

- Heri Albertorio Curriculum VitaeDocument2 pagesHeri Albertorio Curriculum Vitaeapi-237187907No ratings yet

- C81e7global Brand Strategy - Unlocking Brand Potential Across Countries, CulturesDocument226 pagesC81e7global Brand Strategy - Unlocking Brand Potential Across Countries, CulturesClaudia HorobetNo ratings yet

- Simple Past Vs Present Perfect Revisi N Del Intento PDFDocument1 pageSimple Past Vs Present Perfect Revisi N Del Intento PDFHector GuerraNo ratings yet

- Sībuawaith's Parts of Speech' According To ZajjājīDocument19 pagesSībuawaith's Parts of Speech' According To ZajjājīJaffer AbbasNo ratings yet

- Full Download Using and Understanding Mathematics 6th Edition Bennett Solutions ManualDocument36 pagesFull Download Using and Understanding Mathematics 6th Edition Bennett Solutions Manualnoahkim2jgp100% (22)

- The Influence of The Grammatical Structure of L1 On Learners L2 PDFDocument117 pagesThe Influence of The Grammatical Structure of L1 On Learners L2 PDFBDNo ratings yet

- Sapscript SAPScript BillOfLading Documentnt v1.0Document33 pagesSapscript SAPScript BillOfLading Documentnt v1.0Sanjay P100% (1)

- RSpec TutorialDocument22 pagesRSpec TutorialsatyarthgaurNo ratings yet

- Guía S1 Inglés Leidy Meza 1102Document7 pagesGuía S1 Inglés Leidy Meza 1102jose castrilloNo ratings yet

- He Vlach Funeral Laments - Tradition RevisitedDocument24 pagesHe Vlach Funeral Laments - Tradition Revisitedwww.vlasi.org100% (1)

- Hostel Management SystemDocument69 pagesHostel Management Systemkvinothkumarr100% (1)

- Megan Hubbard ResumeDocument2 pagesMegan Hubbard Resumeapi-449031239No ratings yet

- Campus JournalismDocument24 pagesCampus JournalismJoniel BlawisNo ratings yet

- 2023 GPT4All-J Technical Report 2Document3 pages2023 GPT4All-J Technical Report 2Franco J JuarezNo ratings yet

- Reading - The Goals of Psycholinguistics (George A. Miller)Document3 pagesReading - The Goals of Psycholinguistics (George A. Miller)bozkurtfurkan490359No ratings yet

- The Language of Linear B TabletsDocument13 pagesThe Language of Linear B TabletsIDEM100% (2)

- Figure of SpeechDocument4 pagesFigure of SpeechWebcomCyberCafeNo ratings yet

- 4.1 11, YT, DeT Sample TestDocument144 pages4.1 11, YT, DeT Sample TestHamed FroghNo ratings yet

- Sample Catch Up FridaysDocument9 pagesSample Catch Up Fridaysglaidel piol100% (1)

- Elin103semifinals Reviewer 1Document11 pagesElin103semifinals Reviewer 1Nor-ayn PalakasiNo ratings yet

- Marina Spunta, CelatiDocument15 pagesMarina Spunta, CelatiLuisa BianchiNo ratings yet

- CS205-2020 Spring - Lecture 5 PDFDocument37 pagesCS205-2020 Spring - Lecture 5 PDFEason GuanNo ratings yet

- Adverb Clauses - Extra PracticeDocument2 pagesAdverb Clauses - Extra PracticeEliseo HernándezNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan K13Document8 pagesLesson Plan K13Muhammad Hafiz Hafiz Ilham AkbarNo ratings yet

- Reading Comprehension Test For Second Year High SchoolDocument8 pagesReading Comprehension Test For Second Year High SchoolKimi ChanNo ratings yet

- EAPP Handout From Slides 2Document4 pagesEAPP Handout From Slides 2G MARIONo ratings yet

- Diction HandbookDocument69 pagesDiction HandbookTerrence A BrittNo ratings yet

- MD Sadikur Rahman MD Sadikur RahmanDocument1 pageMD Sadikur Rahman MD Sadikur RahmanAnik Deb KanongoNo ratings yet