Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Does National Culture Influence Consumers' Evaluation of Travel Services? A Test of Hofstede's Model of Cross-Cultural Differences

Uploaded by

Esther Charlotte WilliamsOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Does National Culture Influence Consumers' Evaluation of Travel Services? A Test of Hofstede's Model of Cross-Cultural Differences

Uploaded by

Esther Charlotte WilliamsCopyright:

Available Formats

Does national culture influence consumers' evaluation of travel services?

A test of Hofstede's model of cross-cultural differences

John C. Crotts and Ron Erdmann

The authors John C. Crotts is at the Research Centre of Bornholm, Denmark and is Director and Associate Professor at the School of Business and Economics, College of Charleston, Charleston, South Carolina, USA. Ron Erdmann is Senior Market Research Analyst/Deputy Director, Tourism Industries, US Department of Commerce, International Trade Administration, Washington, DC, USA. Keywords Customer satisfaction, Measurement, Tourism, USA, National cultures Abstract The influence of national culture on consumer evaluations of travel services was the focus of this study. Drawing from a representative sample of overseas visitors to the USA, and controlling for socio-economic and trip characteristics, results provide a limited indication that national culture influences how customers evaluate travel services and their willingness to repeat purchase and recommend a service to others. The implications for researchers are that national cultural differences are one of many forces influencing consumer decision making. It is a measurable construct, like gender and socio-economic class, that conditions how consumers interact with others and should be taken into account in our attempts to better understand consumers needs and expectations. Electronic access The research register for this journal is available at http://www.mcbup.com/research_registers/ quality.asp The current issue and full text archive of this journal is available at http://www.emerald-library.com

Managing Service Quality Volume 10 . Number 6 . 2000 . pp. 410419 # MCB University Press . ISSN 0960-4529

Introduction

The role of customer satisfaction in influencing repeat patronage and positive word of mouth is well-documented (Crotts, 1999; Augustyn and Ho, 1998; Kotler et al., 1998; Oppermann, 1998; Heskett et al., 1997). Without meeting or even exceeding customer expectations, a tourism enterprise as well as an entire destination should not expect to find loyal patrons who not only repeat purchase but also ``clone'' themselves among their friends and relatives (Ford and Heaton, 2000; Pine and Gilmore, 1998). Therefore, it has become a critical strategic task for management to systematically gain feedback from their guests as to their service's ability to satisfy needs and meet expectations. The task becomes more problematic where guests come from different national cultures. Do national cultural differences influence consumer evaluations? Cultural psychologists suggest that they do. According to Hofstede (1991), a prominent dimension of culture is the masculinity versus femininity dimension (i.e. competitiveness vs. cooperation) where certain cultures find desirable assertive behavior, while others emphasize behavior that is more modest. The degree to which consumers from a specific culture are willing to provide assertive and critical evaluative responses to consumer satisfaction surveys is a visible sign of this cultural dimension. According to Hofstede, individuals from societies where masculine values prevail more frequently evoke behaviors that are assertive, judgmental and have less concern for the feelings of others, which in turn should be reflected in their consumer satisfaction scores. On the other hand, guests from societies where there is more tenderness and sympathy for others and where assertiveness is not a desirable characteristic should be overtly moderate as to the extent they are willing to provide criticism in their evaluations. If this is true, not accounting for cultural differences in such measures may lead to over-estimating customer satisfaction, customer loyalty and positive word of mouth. This research is organized around the following two questions: (1) Do international visitors from masculine cultures evaluate tourist services more negatively than visitors from more feminine cultures?

410

Does national culture influence consumers' evaluation of travel services?

John C. Crotts and Ron Erdmann

Managing Service Quality Volume 10 . Number 6 . 2000 . 410419

(2) What influence does national culture have in predicting repeat patronage and the probability of positive word of mouth? The research rests on the widely-held assumption that customer satisfaction is linked to customer loyalty and customer loyalty is linked to a firm's profits and future growth potential (Crotts, 1999; Augustyn and Ho, 1998; Kotler et al., 1998; Oppermann, 1998; Heskett et al., 1997). The significance of the study rests on determining if satisfaction measures alone are the best predictors of the probability of repeat patronage and third-party endorsements, or should other social-cultural should be included. International visitors contribute much to the export earnings of tourist receiving nations, generating sales, labor earnings and employment. However, the marketplace is highly competitive. We contend that those destinations that can appreciate the relevant subtleties of cultural differences when gaining feedback from its visitors will have strategic advantages over those which do not.

Literature review

Customer satisfaction has become the buzzword of the 1990s, generating much interest and research among academic researchers. Today, leading hospitality and tourism firms recognize that profits hinge on the perceived level of customer satisfaction and the ability to achieve some level of consumer loyalty. Loyal customers have often been touted to be the profit engines of businesses, generating as much as 80 percent of a firm's total sales and profits through their repeat patronage (Noe, 1998). Even this percentage may be low, in that high-repeat customers also become a firm's willing apostles generating the positive word of mouth that drives new customers to a particular firm (Heskett et al., 1997). Systematically listening to customers allows management to measure how well they are doing in serving their customers and when benchmarked with other firms gain some understanding of their competitive position in the marketplace. Gaining feedback also helps management to identify customer segments who are most predisposed to value their service, as well as the almost satisfied and

dissatisfied who need extra attention in an effort to elevate their user status (Heskett et al., 1997). Performance measures that are simple, consistent and elicit customer feedback on dimensions that are important to the consumer allows management to track performance and predict service outcomes. Only by measuring can a firm become confident in its ability to retain customers and generate positive word of mouth. There are many methods used in gaining customer feedback that are generally accepted as valid and reliable. Fairfield Inns employs touch screen computers asking guests who are checking out to rate or score their performance. The Promus hotel group employs a 100 percent satisfaction guarantee to encourage customer complaints, which are inputted into a reporting system for identifying the root causes of service failures. Arguably the most common customer feedback mechanism is the self-administer survey (Parasuraman et al., 1990). The question arises as to the reliability and validity of these feedback measures particularly in a cross-cultural environment. Cultural values is an umbrella concept that includes such elements as shared values, beliefs and norms that collectively distinguish a particular group of people from others (Pizam et al., 1997). These widely shared values are programmed into individuals in subtle ways from quite an early age (Otaki et al., 1986), are resistant to change (Hofstede, 1991) and remain evident when at home or while traveling abroad (Pizam and Reichel, 1996; Pizam and Sussmann, 1995). Cultural differences have often been purported as the basis for specific ``stereotypes'' given to tourists from specific national origins. For example, residents have been reported to stereotype French and Italians as excessively demanding (Boissevian and Inglott, 1979), English as stiff, socially-conscious and honest (Pi-Sunyer, 1977), and American as cautious, calculating and purposeful (Brewer, 1978). Though there is considerable debate as to the accuracy of such national stereotypes (Dann, 1993), there is little doubt that culture is one of many forces influencing consumer decision making (You et al., 2000; Pizam and Sussmann, 1995; Assael, 1987). According to Pizam and colleagues, the focus of tourism research in this area should be to identify and understand the cultural differences that are not only scientifically valid but provide

411

Does national culture influence consumers' evaluation of travel services?

John C. Crotts and Ron Erdmann

Managing Service Quality Volume 10 . Number 6 . 2000 . 410419

information useful to practitioners. We contend that determining the extent to which national culture influences a consumer's willingness to report dissatisfaction and its subsequent influence on the likelihood that the customer will recommend the service to others are issues worthy of investigation. National culture has been defined in hundreds of ways (Erez and Early, 1993). Arguably, the most widely utilized dimensions of culture are the five presented by Hofstede (1980) and his colleagues (Hofstede and Bond, 1988) from their instrument called the Values Survey Module or VSM. Briefly, they are: (1) power distance (a tolerance for class differentials in society); (2) individualism (the degree to which welfare of the individual is valued more than the group); (3) masculinity (achievement orientation, competition, and materialism); (4) uncertainty avoidance (intolerance of risk; and later, (5) the Confucian dynamic, or long-term orientation (stability, thrift, respect for tradition and the future). Drawing from Hofstede's (1991) research, Asian societies tend to score high in long-term orientation, collectivism and power distance, but mixed in terms of masculinity and uncertainty avoidance characteristics. On the other hand, Western societies tend to score low long-term orientation, collectivism, power distance and uncertainty avoidance, but mixed in terms of masculinity. The masculinity index was selected since it most clearly articulates the cultural traits that are assertive, judgmental and have less concern for the feelings of others, which in turn should be reflected in their consumer satisfaction scores.

Method

The data for the study were from the 1996, 1997 and 1998 Inflight Survey of Overseas Visitors to the United States. Annually, the US Department of Commerce's Tourism Industries surveys more than 80,000 overseas visitors on regularly scheduled flights with self-administered questionnaires distributed in-flight by airline flight crew personnel after departure from the USA. Employed is a

random cluster sampling procedure, where all passengers on randomly selected flights. on randomly selected days, are administered the self-administrated survey instrument. Currently there are 61 US and foreign flag carriers cooperating with the survey and response rates are generally quite high, averaging 58 percent (Tourism Industries, 1999). The survey itself is composed of 29 questions and is available in 11 languages. Each language version of the survey has been forward and back translated to insure uniformity among the versions. The purpose of the survey is to elicit visitor feedback and travel party and trip characteristics of overseas visitors that firms can use to better understand and serve the overseas markets. Two of these questions ask respondents to rate the quality of the airport in which they had just departed, as well as the airline they were using, on a variety of attributes along a five point scale (where 5 = excellent; 1 = poor). A third question attempts to estimate customer loyalty by asking respondents if they would ``choose or recommend the airline they were using on their next trip on this route''. Responses are recorded along a five point scale where 1 = definitely would, 2 = probably would, 3 = probably would not, 4 = definitely would not and 5 = unsure. These three ratings were used as dependent measures in the subsequent analysis. The principle limitation of the data is that the name of the airline the respondent evaluates is considered proprietary information that is not released to researchers. For purposes of the analysis, the dataset was limited to those respondents who indicated their country of birth was the UK, Germany, Japan, Brazil and Taiwan. These countries were selected for their significance to the USA's overseas market (i.e. in 1998, 55.1 percent of overseas arrivals resided in these six nations) but also due to their unique scores along Hofstede's (1980, 1991) national culture measures. In addition, the selection of country of birth was made over country of citizenship since research has shown that virtually all of the cultural dimensions of interest are learned by the age of ten years and remain relatively immune to change over the remaining life span (Hofstede, 1991). The second phase in the sample selection process delimited the final sample to those visitors who had not visited the USA in the previous five years; whose primary trip

412

Does national culture influence consumers' evaluation of travel services?

John C. Crotts and Ron Erdmann

Managing Service Quality Volume 10 . Number 6 . 2000 . 410419

purposes were deemed discretionary (i.e. holidays, leisure, visiting friends and relatives); who were between the ages of 45 to 60 years of age; and were employed in managerial or professional occupations. Hofstede (1991) warned that comparisons of countries should always be based upon people of the same socio-economic groupings since social class also influences behavior. Controlling for the number of previous visits (e.g. no previous visits to the USA in past five years) and trip purpose (e.g. discretionary) was also deemed appropriate since the trip planning characteristics can be quite different between these groups (Oppermann, 1998; Guy et al., 1990, Gitelson and Crompton, 1984) and not controlling for their effects may have biased the results. The specific age and occupation categories were selected by way of the frequencies of responses to preserve the sample sizes while still controlling as much as possible the influence on the study's dependent measures. The net effect of employing the five criteria reduced the entire database to 983 respondents, or less than 1 percent of the available database. Subjects were next assigned to one of three groups based upon Hofstede's (1980, 1991) national cultural rankings along the masculinity index. Specifically, subjects from Japan were assigned to the high masculine group (Japan ranked first of 53 nations), subjects from the UK and Germany (ranks tied at ninth/tenth of 53 nations) were assigned to the middle masculinity group and subjects from Brazil and Taiwan (27th and 32nd of 53 nations) to the low masculinity group. Though these measures of national culture are dated, Hofstede notes that national cultures change very slowly and when:

Cultures shift, F F F they shift together, so that the differences between them remain intact (1991, p. 77).

which to explore if national culture indeed predicts tourist behavior. Specifically, individuals born in a cultural setting where modest behavior is the norm (i.e. femininity) will be less critical in the evaluations of tourist services when compared to respondents born in cultural settings where aggressive (i.e. masculine) behaviors are the norm. Furthermore, national cultural differences will be evident in explaining differences in customer loyalty as reflected by visitors' self reported intentions to make a repeat purchase and recommend the service to others.

Results

Description of sub groups Describing the sub samples' social demographic characteristics would be meaningless since the sampling criteria eliminated most differences. However, a number of issues are interesting from a methodological perspective. First, self reports of country of birth differed from country of residence in only nine (0.9 percent) of the 983 cases. This was somewhat disappointing in that a priori we wished to explore the effects of culture of residents on culture of birth values. Though an intriguing issue, such an analysis is not often possible since one measure tends to mirror the other even in large datasets of this nature. Even with the sampling criteria being employed, further steps were warranted to test for differences between the sub sample groups. When asked to indicate their gender, approximately three-quarters of each sample's respondents indicated they were female (see Table I). However, the proportion of respondents who were female was significantly higher in the high masculine group at 84.4 percent. Gender, like nationality of birth, is an important factor to account for in analyses of this nature since men, on average, are programmed with tougher values than women, though the gap between them varies by country. According to Hofstede (1991), the gap between genders rises along with masculinity scores, implying that the higher representation of females in the high masculine group should produce more moderate or less harsh evaluations in contrast to what was predicted. Though gender differences should be anticipated, Hofstede has warned that they are:

Given that the six nations selected in this study were chosen for their unique differences, the relative national cultural differences between them should have remained unchanged. In all, three matched samples were derived where 582 (59.2 percent) subjects were assigned to the high masculine group, 283 (28.8 percent) to the middle group and 118 (12.0 percent) to the low masculine group again for a total of 983 respondents. These national culture measures and their subsequent groupings provided a means in

413

Does national culture influence consumers' evaluation of travel services?

John C. Crotts and Ron Erdmann

Managing Service Quality Volume 10 . Number 6 . 2000 . 410419

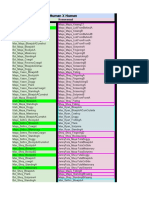

Table I Description of the samples national cultural groupings by gender and where seated on aircraft Low Medium 26.0 74.0 100 High 16.0 84.4 100 Chi 13.60, p < 0.001 1.5 10.4 88.1 100 Chi 22.63, p < 0.000 582

Gender Male (percent) Female (percent)

23.3 76.7 100

Where are you sitting on the airplane? 1st class (percent) Business class (percent) Economy (percent)

0.8 4.2 95.0 100 118

0.3 2.6 97.0 100 283

Sample sizes

F F F statistical rather than absolute, [implying] that there is an overlap between the values of men and women so that any given value may be found among men and women (Hofstede, 1991, p. 85).

To further determine, where possible, that the sub groups were matched in all important areas, crosstabs were produced on where the respondents were sitting on the aircraft. Approximately nine out of ten respondents indicated they were sitting in the economy or coach section of the airplane. Though the distribution across the three groupings was similar, respondents in the high masculine group as a whole reported sitting in business class significantly more often than the other two groupings (see Table I). Predicting the potential effect of such differences is difficult. On the one hand, the vast majority of published complaints in newspapers indicate that passengers in the economy class experience the most frustration due to the frugal level of service. On the other hand, perceived service quality is often defined as the value received for the price paid (Murphy and Pritchard, 1997; Chang and Wildt, 1994) so first-class and business-class passengers may be more discerning when it comes to evaluating service quality when compared to their economy-class counterparts. However, such differences should be revealed in the level of service and not so much in the airport or airline facilities that made up the majority of dimensions respondents could evaluate. Does national culture influence customer evaluations? Respondents ratings of airport facilities, on average, were in the average to good range.

Only the ratings of concessionary prices dipped into the poor range (Table II). As predicted, respondents assigned to the low masculinity national culture group reported on average more positive evaluation of airport facilities. Moreover, the between group differences were most pronounced when respondents in the low to middle masculinity groups were compared to respondents in the high masculinity (i.e. Japan) group. Both Sceffe and Donnett T3 post hoc tests revealed significant differences between the high and low masculinity groups on all ten criteria in the directions predicted. On the other hand, differences between the medium masculinity group with either the low or high masculinity groups were few. Though the average ratings across all three groups were in the direction predicted, respondents assigned to the medium group reached statistical significance only in ratings of quality concession goods and airport security. Similar differences were revealed comparing the responses of the lower to middle masculinity groups with the high masculine group on their evaluations of the airflight (Table III). Respondents in the high masculine grouping reported on average lower ratings of airline service quality than their lower masculine counterparts on 14 of the 15 evaluative criteria. However, no statistical differences were found between the lower and middle masculinity groups. It is worth noting that the three groups virtually mirrored one another in terms of their average rating of airline ability to have an on-time departure. On a relative basis, this dimension of service quality was ranked low by all three groups, suggesting that when

414

Does national culture influence consumers' evaluation of travel services?

John C. Crotts and Ron Erdmann

Managing Service Quality Volume 10 . Number 6 . 2000 . 410419

Table II ANOVA table mean differences between national cultural groups in evaluation of US airport facilities Low Medium 3.90b 3.78b 3.74b 3.92b 3.20a,c 2.60b 3.48b 3.36b 3.59a,c 3.54b High 3.62a,b 3.31a,b 3.26a,b 3.47a,b 3.07a,b,c 2.52a,b 3.05a,b 3.00a,b 3.33a,b,c 3.32a,b

F

12.31 30.5 33.03 36.89 17.58 5.31 31.67 22.15 28.15 15.45

p-value

0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.005 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000

Dimension rated Airport access Ground transportation Terminal convenience Cleanliness Concession goods Concession prices Terminal seating International facilities Security Overall evaluation

3.92a 3.84a 3.82a 3.96a 3.68a,b 2.97a 3.73a 3.53a 3.93a,b 3.74a

Notes: Scored on a five point scale where 5 = excellent and 1 = poor Mean values with the same subscripts significantly differ from one another employing both Scheffe and Donnett T3 tests at p < 0.01

Table III ANOVA table mean differences between national cultural groups in evaluation of airlines Low Medium 3.90b 3.76b 3.81b 3.55b 3.95b 3.58 3.65b 4.07b 4.02b 3.29b 3.13a 3.47b 3.63b 3.80b 3.86b High 3.57a,b 3.23a,b 3.43a,b 3.14a,b 3.41a,b 3.57 3.33a,b 3.78a,b 3.58a,b 2.97a,b 2.86a 3.07a,b 3.14a,b 3.46a,b 3.50a,b

F

17.12 26.01 15.63 26.60 34.50 0.044 10.14 10.77 28.74 18.64 8.22 28.28 42.11 19.88 24.61

p-value

0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.957 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000

Dimension rated Convenient schedules Ticket price Reservation service Check-in waiting time Check-in personnel Departure time Food and beverage Flight attendants Cabin cleanliness Cabin noise level Seat comfort Cabin layout Carry on storage Overall evaluation of aircraft Overall evaluation of airline

3.99a 3.34a 3.75a 3.66a 3.79a 3.54 3.55a 3.98a 3.88a 3.36a 3.13 3.54a 3.68a 3.84a 3.85a

Notes: Scored on a five-point scale where 5 = excellent and 1= poor Mean values with the same subscripts significantly differ from one another employing both Scheffe and Donnett T3 tests at p < 0.01

delay occurs it has a negative influence on ratings, regardless of cultural norms. What influence does national culture have in predicting customer loyalty? Asked ``Would you choose or recommend this airline for your next trip on this route?'', 18.8 percent indicated that they definitely would, 59.6 percent said they probably would, 5.0 percent they probably would not, 1.7 percent definitely would not and 12.0 percent were unsure. Responses to this question were used to classify into two separate groups, which are similar to Heskett et al.'s (1997) classification

strategy. They were the definite repeat purchasers and third party endorsers (hereafter refered to as loyals) comprised of 216 respondents and the unlikely to repeat purchase or recommend to others (hereafter refered to as potential defectors) comprised of 190 respondents. The large 59.6 percent of the sample who indicated they probably would repeat purchase was dropped from the analysis in an effort to create the greatest possible distances between the bivariate loyalty groups. A canonical discriminant analysis with the stepwise procedure was conducted with the

415

Does national culture influence consumers' evaluation of travel services?

John C. Crotts and Ron Erdmann

Managing Service Quality Volume 10 . Number 6 . 2000 . 410419

loyals and defectors variable as the group membership variable (1, 0). The purpose of the disciminant analysis was to identify the relative importance of national culture in combination with satisfaction measures in discriminating between loyalty and defectors customers. In addition, the two dummy variables describing the compartment of the aircraft in which the respondent was sitting (i.e. first class, business class, economy class) and gender were included to test other competing hypotheses simultaneously. The stepwise procedure provided a means to determine the relative importance of each of the variables to significantly increase the loyalty prediction. Again the analysis rests on the assumption that not accounting for socialcultural differences in satisfaction measures may lead to less accurate loyalty measures. A test of equality of group means revealed significant differences between those respondents in the loyal and defector groups on five of the six independent variables. Table IV shows the means and statistical differences of the independent variables relative to the group membership. As predicted, loyalty groups differed significantly on satisfaction measures. Subjects indicating high loyalty tendencies rated the aircraft and flight in the good to excellent range while subjects revealing terrorist tendencies rated the same attributes in the fair to average range. In addition, subjects who indicated that they were born in the less masculine societies a measure of national culture reported greater loyalty tendencies than those born in more masculine societies. Conversely, those subjects reporting their country of birth in masculine societies were more likely to report defector attitudes. Significant differences between males and females were also found where females were most likely to report loyalty than males. Surprisingly, no significant differences were found between compartments in the aircraft in which the passenger was sitting.

Results of the canonical discriminate function, shown in Table V, reveals the discriminant function was statistically significant, as measured by the chi-square statistic. With an eigenvalue of 0.124 and a canonical correlation value of 0.744, the variables accounted for a significant amount of the variance. The Wilks lambda which is the ratio of the within-group sum of squares to the total sum of squares for the model indicated that both groups were significantly different from one another. Of particular importance in this study was the need to identify which variables would be retained in the stepwise procedure as well as their relative importance in discriminating between loyal and defector groups. Step 1 retained respondents' overall evaluation of the flight, step 2 the national culture measure and step 3 respondents' overall evaluation of the aircraft (Table VI). Gender and where respondents were sitting on the aircraft were not significant as to their ability to reduce the Wilks lambda values and account for the residual variance. The final step in the discriminant analysis was to test the function's ability to correctly classify respondents into the appropriate group. The classification accuracy of the model achieved a relatively high accuracy hit rate at 88.4 percent where 80.2 percent of the defector group and 94.9 percent of the loyal group could be correctly classified.

Discussions and implications

Before summarizing the results of this study and discussing their implications, it is important to review this study's limitations. First, the results should not be construed to be representative of all tourists from Japan, the UK, Germany, France, Brazil and Taiwan, let alone those who visit the USA, due to the highly delimited nature of the sample. Without additional research it is far too premature to make such generalizations.

Table IV Test of equality of group means: loyalty group membership Independent variables Evaluation of aircraft Evaluation of flight National culture Gender Compartment in aircraft Loyal 4.23 4.28 1.04 1.77 2.94 Defectors 2.96 2.90 1.61 1.90 2.93

F

243.66 258.31 51.97 7.73 0.24

p<

0.000 0.000 0.000 0.006 0.623

416

Does national culture influence consumers' evaluation of travel services?

John C. Crotts and Ron Erdmann

Managing Service Quality Volume 10 . Number 6 . 2000 . 410419

Table V Summary of three-group discriminant analysis Function 1 Eigen value 1.27 Canonical correlation 0.748 Wilks lambda 0.440 2 Chi-square 23.71

p-value

0.000

Table VI Three step solution to canonical discriminant analysis Step Variable(s) included 1 2 3 Evaluation of flight Evaluation of flight, national culture Evaluation of flight, national culture, evaluation of aircraft Variables not retained in discriminate functiona Gender Compartment in aircraft

a

Wilks lambda 0.516 0.462 0.446 0.095 0.090

F

258.31 159.78 113.12 0.331 0.930

p-value

0.000 0.000 0.000

Note:

F to enter 3.84, F to remove 2.71

Instead, the focus should be limited to a test of theory examining the influence of national culture on consumers' evaluations of a service as well as their intent to repeat purchase and recommend a firm to others. Second, it is impossible to rule out that variations in quality of both the airports and airlines contributed to the reported differences. Future research that is focused on a specific flight and a specific airport is warranted to validate this study's findings. Nevertheless, the findings of this study provide tentative evidence in support of Hofstede's conceptual framework that national culture influences consumer's willingness to report dissatisfaction. Responses from matched samples of international visitors revealed a willingness of respondents from high masculine societies to report dissatisfaction more often then those from low to moderate masculine societies. Though the differences were small, they were nevertheless statistically significant and consistent in 24 out of 25 cases. These findings suggest that firms who serve visitors from countries where assertive behavior is encouraged should expect lower average satisfaction measures when compared to visitors from less masculine societies. These same national cultural differences also proved to be reasonably good predictors of an airline's most loyal and least loyal customers. Second only in predictive power to how subjects rated the overall airflight, national cultural differences as measured on the masculinity index proved a better predictor than respondents' evaluation of the

aircraft. This finding supports Augustyn and Ho's (1998) assertion that in the effort to win the hearts and minds of consumers:

One seat on an airplane is much like any other. It is the passenger service that makes the difference in the treatment by (all) front-line personnel (p. 72).

Based upon this study's findings, we also would add that the consumers themselves play a role in the process. Specifically, respondents who indicated strong loyalty measures were found to be from less masculine cultures, while those reporting strong customer defection attitudes were generally found to be from the more masculine societies. These findings can be interpreted in one of three ways. First, it is possible that respondents from the low masculine societies (i.e. Brazil and Taiwan) flew on better aircraft and received better services (or perceived such) as compared to those from more masculine societies (i.e. Japan). Given that the respondents from all three loyalty groups were reporting on airline experiences spanning 36 months, it is hard for us to imagine that each group was experiencing consistently bad or good service from their respective carriers. A second possible explanation is that customers from low masculine societies may be more willing to have sympathy for others and simply disregard perceived shortcomings when compared to others from more masculine societies. A third possible explanation is that customers from these same feminine societies when asked may be less willing to criticize and

417

Does national culture influence consumers' evaluation of travel services?

John C. Crotts and Ron Erdmann

Managing Service Quality Volume 10 . Number 6 . 2000 . 410419

report likely defection while individuals from masculine societies are only too happy to do so. Though we can provide no evidence as to which interpretation is accurate, it is our contention that the latter is true. A popular television show which airs in Europe, depicting a day in the life of London's Heathrow Airport, provides antidotal evidence in support of the reservedness of certain national cultures to avoid overtly assertive behaviors. In one episode, a small carrier serving the London to Pakistan route was delayed for departure for seven hours while it was continually bumped from the queue in refueling priorities in favor of a more dominant carrier. The camera panned the departure lounge at regular intervals, revealing a concerned but seemingly polite and calm group of Pakistani passengers, along with an increasingly frustrated British shift supervisor. Tempers did flare in the final hour, but after the plane's departure, the exasperated supervisor mentioned, when interviewed, that his Pakistani passengers were far more patient that other customers would have been. He offered that most British passengers would have demanded to be bumped to another airline after three hours and American passengers would have threatened to sue after four. Pakistan is tied in rank with Malaysia at 25/26, Britain is tied with Germany at a rank of 9/10 and America is ranked 15 along Hofstede's masculinity index. What implications do this study's findings have for analyzing customer satisfaction data? Though customer ratings appear to be influenced by national culture, the mean differences in evaluation scores were small and from a practical standpoint do not warrant re-centering. In the preliminary stage of the analysis, box plots revealed that at times subjects in the low masculine group would use the entire negative range of evaluation responses in evaluating such services. The principal implication for management is that on the whole, they should be more cognizant of customers from low and even middle masculine cultures not to openly complain. For those firms serving customers from high masculine societies, there may be little problem in eliciting the voice of the malcontents. The former may require more tact and probing than the later to identify problems in need of recovery and avoid the same mistakes in the future.

What are the implications of this study to our understanding of the customer satisfaction link to customer loyalty? First and foremost, the best predictor by far of customer loyalty and defection measures was the overall customer satisfaction with the flight itself. Second, national cultural differences were shown not only to influence or moderate satisfaction measures but also loyalty measures too. Such a linkage was likely since both satisfaction measures and loyalty measures are attitudinal measures and where one social cultural measure influences one factor it will likely influence the other. However, national culture was shown to be a slightly better predictor of customer loyalty measures than customers' evaluation of the overall aircraft. Perhaps most important, national culture was significantly better at predicting loyal and defector measures than gender or compartment in the aircraft where seated. Airlines are quick to note the discerning nature of the first class and business class passengers. These findings alone should suggest that national culture as defined along Hofstede's masculinity index should also be considered in their efforts to win over the minds and loyalty of customers. The research supports Dann's (1993) conclusions that national cultural difference is one of many forces influencing consumer decision making. We contend it is a measurable construct, like gender and socio-economic class, that conditions how individuals interact with others and should be taken into account in our attempts to better understand consumers' needs and expectations.

References

Assael, H. (1987), Consumer Behavior and Marketing Action, PWS-Kent Publishing Co., Boston, MA. Augustyn, M. and Ho, S. (1998), ``Service quality and tourism'', Journal of Travel Research, Vol. 37 No. 3, pp. 71-5. Boissevian, J. and Inglott, P. (1979), ``Tourism in Malta'', in De Kadt, E. (Ed.), Tourism: Passport to Development?, Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp. 265-84. Brewer, J. (1978), ``Tourism business and ethnic categories in a Mexican town'', in Smith, V. (Ed.), Tourism and Behavior, College of William and Mary, Williamsburg, VA. Chang, T.-A. and Wildt, A.R. (1994), ``Price, product information and purchase intention: an empirical study'', Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, Vol. 22 No. 1, pp. 16-27.

418

Does national culture influence consumers' evaluation of travel services?

John C. Crotts and Ron Erdmann

Managing Service Quality Volume 10 . Number 6 . 2000 . 410419

Crotts, J. (1999), ``Consumer decision making and prepurchase information search'', in Mansfield, Y. and Pizam, A. (Eds), Consumer Behavior in Travel and Tourism, Haworth Press, Binghamton, NY. Dann, G. (1993), ``Limitations in the use of nationality and country of residence variables'', in Pearce, D. and Butler, R. (Eds), Tourism Research: Critiques and Challenges, Routledge, London, pp. 88-112. Erez, M. and Earley, P.C. (1993), Culture, Self Identity and Work, Oxford University Press, New York, NY. Ford, R. and Heaton, C. (2000), Managing the Guest Experience, Delmar Thomson Learning, Albany, NY. Gitelson, R.J. and Crompton, J.L. (1984), ``Insights into the repeat vacation phenomenon'', Annals of Tourism Research, Vol. 11 No. 1, pp. 199-217. Guy, B.S., Curtis, W. and Crotts, J. (1990), ``First time visitors' learning of a foreign destination environment'', Annals of Tourism Research, Vol. 17 No. 3. Heskett, J., Sasser, W.E. and Schlesinger, L.A. (1997), The Service Profit Chain, The Free Press, New York, NY. Hofstede, G. (1980), Culture's Consequences, Sage Publications, Beverly Hills, CA. Hofstede, G. (1991), Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind, McGraw-Hill, London. Hofstede, G. and Bond, M.H. (1988), ``The Confucius connection: from cultural roots to economic growth'', Organizational Dynamics, Vol. 16 Spring, pp. 5-21. Kotler, P., Bowen, J. and Makens, J. (1998), Marketing for Hospitality and Tourism, Prentice-Hall, Upper Saddle River, NJ. Murphy, P. and Pritchard, M. (1997), ``Destination pricevalue perceptions: an examination of origin and seasonal influences'', Journal of Travel Research, Vol. 35 No. 3, pp. 16-22. Noe, F. (1998), ``Book review: the service profit chain'', Tourism Analysis, Vol. 3 No. 3/4, pp. 215-18.

Oppermann, M. (1998), ``Destination threshold potential and the law of repeat visitation'', Journal of Travel Research, Vol. 37 No. 2, pp. 131-8. Otaki, M., Durrett, M.E., Richards, P., Nyquist, L. and Pennebaker, J. (1986), ``Maternal and infant behavior in Japan and America'', Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, Vol. 17 No. 3, pp. 251-68. Parasuraman, A., Zeithaml, V. and Berry, L. (1990), Delivering Quality Service, Free Press, New York, NY. Pine, B., Gilmore, Jo. and Gilmore, Ja. (1998), ``Welcome to the experience economy'', Harvard Business Review, July-August, pp. 97-105. Pi-Sunyer, O. (1977), ``Through native eyes: tourists and tourism in Catalan maritime community'', in Smith, V. (Ed.), Host and Guests: The Anthropology of Tourism, University of Pennsylvania Press, Baltimore, MD. Pizam, A. and Reichel, A. (1996), ``The effect of nationality on tourist behavior: Israeli tour-guides' perceptions'', Journal of Hospitality and Leisure Marketing, Vol. 4 No. 1, pp. 23-49. Pizam, A. and Sussman, S. (1995), ``Does nationality effect tourist behavior?'', Annals of Tourism Research, Vol. 22 No. 2, pp. 901-17. Pizam, A., Pine, R., Mok, C. and Shin, J.Y. (1997), ``Nationality versus industry cultures: which has greater effect on managerial behavior?'', International Journal of Hospitality Management, Vol. 16 No. 2, pp. 127-45. Tourism Industries (1999), Inflight Survey of Overseas Arrivals to the United States, US Department of Commerce, Washington, DC. You, X., O'Leary, J., Morrison, A. and Hong, G.-S. (2000), ``A cross-cultural comparison of travel push and pull factors: United Kingdom versus Japan'', International Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Administration, Vol. 1 No. 3.

419

You might also like

- The Impacts of CountryDocument18 pagesThe Impacts of CountryKukuh RestuNo ratings yet

- Budget HotelsDocument33 pagesBudget HotelsJay ArNo ratings yet

- Article On Sem4 PDFDocument9 pagesArticle On Sem4 PDFdanikapanNo ratings yet

- 2020 Ijhm PDFDocument10 pages2020 Ijhm PDFnkorfNo ratings yet

- Customer Satisfaction HotelDocument10 pagesCustomer Satisfaction HotelRinni Taroni RNo ratings yet

- Key Success Factors of Tourist Satisfaction in Tourism Services ProviderDocument6 pagesKey Success Factors of Tourist Satisfaction in Tourism Services Providerpatricia de roxasNo ratings yet

- Determinants of Tourist Satisfaction and Intention To ReturnDocument19 pagesDeterminants of Tourist Satisfaction and Intention To ReturnavNo ratings yet

- How Do Guests Choose A HotelDocument10 pagesHow Do Guests Choose A HotelHazrul ChangminNo ratings yet

- Articles Job SatisfactionDocument5 pagesArticles Job Satisfactionrakhshanda_khan19No ratings yet

- E Wom9 PDFDocument5 pagesE Wom9 PDFdanikapanNo ratings yet

- 09 Chapter2Document38 pages09 Chapter2Gaurav Singh RathoreNo ratings yet

- Tourism Management: Panagiotis Stamolampros, Dimitrios Dousios, Nikolaos Korfiatis, Efthymia SymitsiDocument18 pagesTourism Management: Panagiotis Stamolampros, Dimitrios Dousios, Nikolaos Korfiatis, Efthymia SymitsinkorfNo ratings yet

- Tu MamáDocument5 pagesTu MamáPepeNo ratings yet

- Rajeshwari Final ReportDocument53 pagesRajeshwari Final ReportLakshmi SaraswathiNo ratings yet

- REVIEW OF RELATED LITERATURE-evaluationDocument16 pagesREVIEW OF RELATED LITERATURE-evaluationMaylyn Fecog SARA-ANNo ratings yet

- Customer Satisfaction in The Hotel Industry A Case Study From Sicily - 2010Document11 pagesCustomer Satisfaction in The Hotel Industry A Case Study From Sicily - 2010kokenyNo ratings yet

- The Relative Impact of Competitiveness Factors andDocument16 pagesThe Relative Impact of Competitiveness Factors andNinh NguyenNo ratings yet

- Article 17Document9 pagesArticle 17Sdiri MongiaNo ratings yet

- Destination Perceived ValueDocument9 pagesDestination Perceived ValueNihat ÇeşmeciNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3 Tourism MarketingDocument20 pagesChapter 3 Tourism MarketingPearlane Hope LEHAYANNo ratings yet

- Music, Scent and Time Preferences For Waiting LinesDocument18 pagesMusic, Scent and Time Preferences For Waiting LinesomarNo ratings yet

- Examining The Structural Relationships of Destination Image, Tourist Satisfaction PDFDocument13 pagesExamining The Structural Relationships of Destination Image, Tourist Satisfaction PDFAndreea JecuNo ratings yet

- Thesis Dependency TheoryDocument7 pagesThesis Dependency Theorymarypricecolumbia100% (2)

- The Relationship Between Customer Satisfaction and Customer Loyalty in The Banking Sector in SyriaDocument9 pagesThe Relationship Between Customer Satisfaction and Customer Loyalty in The Banking Sector in Syriamr kevinNo ratings yet

- Academic PaperDocument6 pagesAcademic PaperLee Quilong-QuilongNo ratings yet

- Measuring Customer Satisfaction: Exploring Customer Satisfaction’s Relationship with Purchase BehaviorFrom EverandMeasuring Customer Satisfaction: Exploring Customer Satisfaction’s Relationship with Purchase BehaviorRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (6)

- JournalofInvestmentManagement VDC Ms CC GDG PDFDocument13 pagesJournalofInvestmentManagement VDC Ms CC GDG PDFAnonymous dCNH4ONo ratings yet

- A Theoretical Model of The Impact of A Bundle of Determinants Visiting and Shopping IntentionsDocument13 pagesA Theoretical Model of The Impact of A Bundle of Determinants Visiting and Shopping IntentionsGrace HoNo ratings yet

- Customer LoyaltyDocument47 pagesCustomer LoyaltyAlexandra SimionNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Service Quality On Tourism IndustryDocument22 pagesThe Impact of Service Quality On Tourism IndustryAzamhaghkhahNo ratings yet

- Relationships Among Customer Satisfaction, Delight, and Loyalty in The Hospitality IndustryDocument28 pagesRelationships Among Customer Satisfaction, Delight, and Loyalty in The Hospitality IndustryLucky GameNo ratings yet

- Thesis Destination ImageDocument5 pagesThesis Destination Imagedwsmpe2q100% (2)

- Customer SatisfactionDocument7 pagesCustomer SatisfactionSSEMATIC RAQUIBNo ratings yet

- Hultman Et Al 2015 Achieving Tourist Loyalty Through Destination Personality Satisfaction and IdentificationDocument5 pagesHultman Et Al 2015 Achieving Tourist Loyalty Through Destination Personality Satisfaction and IdentificationMageshri ChandruNo ratings yet

- Hotel Service Quality ThesisDocument8 pagesHotel Service Quality Thesisvaivuggld100% (2)

- Chatterjee 2020Document13 pagesChatterjee 2020Mai NguyenNo ratings yet

- An Overview of Experiential Value in Coffee ShopsDocument6 pagesAn Overview of Experiential Value in Coffee ShopsAdnan Rasheed ParimooNo ratings yet

- Effect of Environment, Colour and Music On Customer Loyalty in Restaurants and Coffee ShopsDocument15 pagesEffect of Environment, Colour and Music On Customer Loyalty in Restaurants and Coffee Shopsscd1990No ratings yet

- S#196712355Authored byDocument17 pagesS#196712355Authored byMichael KaraniNo ratings yet

- Brand Love: Mediating Role in Purchase Intentions and Word-of-MouthDocument9 pagesBrand Love: Mediating Role in Purchase Intentions and Word-of-MouthGowri J BabuNo ratings yet

- Consumers Products and Services Value PerceptionDocument5 pagesConsumers Products and Services Value PerceptionAl'ellisNo ratings yet

- Customer Loyalty Marketing Research - A Comparative Approach Between Hospitality and Business JournalsDocument12 pagesCustomer Loyalty Marketing Research - A Comparative Approach Between Hospitality and Business JournalsM Syah RezaNo ratings yet

- David Starr GlassDocument2 pagesDavid Starr GlassRiddhi SoniNo ratings yet

- Literature Review of BIG BAZAARDocument3 pagesLiterature Review of BIG BAZAARSudipRanjanDas67% (6)

- Malaysia Healthcare Tourism: Accreditation, Service Quality, Satisfaction and LoyaltyFrom EverandMalaysia Healthcare Tourism: Accreditation, Service Quality, Satisfaction and LoyaltyNo ratings yet

- Factors Affecting Consumers' Switching IntentionsDocument8 pagesFactors Affecting Consumers' Switching IntentionssurajitbijoyNo ratings yet

- Reasearch Paper NPSDocument8 pagesReasearch Paper NPSarun kumarNo ratings yet

- Relation Between Cultural Intelligence and Customer SatisfactionDocument25 pagesRelation Between Cultural Intelligence and Customer SatisfactionPrabhjot SeehraNo ratings yet

- Thesis On Customer Satisfaction in HotelsDocument5 pagesThesis On Customer Satisfaction in HotelsPapersWritingHelpSingapore100% (2)

- The Congruence Effect Between Product Emotional Appeal and CountrDocument33 pagesThe Congruence Effect Between Product Emotional Appeal and CountrKeyanna YoungeNo ratings yet

- Relationship Between HotelDocument15 pagesRelationship Between HotelCooobeyNo ratings yet

- Maiyaki, 2013Document21 pagesMaiyaki, 2013LihinNo ratings yet

- Web 2.0 and Impacts in Tourism: Romeu Lopes José Luís Abrantes Elisabeth KastenholzDocument3 pagesWeb 2.0 and Impacts in Tourism: Romeu Lopes José Luís Abrantes Elisabeth KastenholzMarijana BilicNo ratings yet

- Stringam and Gerdes - 2010 - An Analysis of Word-of-Mouse Ratings and Guest ComDocument25 pagesStringam and Gerdes - 2010 - An Analysis of Word-of-Mouse Ratings and Guest ComGambler ShinNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Word of Mouth When Booking A Hotel C PDFDocument23 pagesThe Impact of Word of Mouth When Booking A Hotel C PDFAusteja AbromaviciuteNo ratings yet

- Mina Seraj - Ewom PDFDocument16 pagesMina Seraj - Ewom PDFdanikapanNo ratings yet

- Factors Affecting On Customer Satisfaction in Retail BankingDocument8 pagesFactors Affecting On Customer Satisfaction in Retail BankinghienhtttNo ratings yet

- The Reign of the Customer: Customer-Centric Approaches to Improving SatisfactionFrom EverandThe Reign of the Customer: Customer-Centric Approaches to Improving SatisfactionNo ratings yet

- Culture GoldDocument12 pagesCulture GoldEsther Charlotte WilliamsNo ratings yet

- Cultural Differences in Travel Risk PerceptionDocument20 pagesCultural Differences in Travel Risk PerceptionEsther Charlotte Williams100% (2)

- A Cross-Cultural Comparison of Travel Push and Pull FactorsDocument28 pagesA Cross-Cultural Comparison of Travel Push and Pull FactorsEsther Charlotte WilliamsNo ratings yet

- Multi-Faceted Tourist Travel Decisions - A Constraint-Based Conceptual Framework To Describe Tourists' Sequential Choices of Travel ComponentsDocument8 pagesMulti-Faceted Tourist Travel Decisions - A Constraint-Based Conceptual Framework To Describe Tourists' Sequential Choices of Travel ComponentsEsther Charlotte WilliamsNo ratings yet

- User-Generated Content and Travel A Case Study On Trip AdvisorDocument12 pagesUser-Generated Content and Travel A Case Study On Trip AdvisorEsther Charlotte Williams100% (1)

- Effects of WOM and Product - Attribute Information On Persuasion An Accessibility Diagnosticity PerspectiveDocument10 pagesEffects of WOM and Product - Attribute Information On Persuasion An Accessibility Diagnosticity PerspectiveEsther Charlotte WilliamsNo ratings yet

- This Is A Book For Parents of Gay Kids: A Question & Answer Guide To Everyday Life (Excerpt)Document28 pagesThis Is A Book For Parents of Gay Kids: A Question & Answer Guide To Everyday Life (Excerpt)ChronicleBooks75% (4)

- Historically Authentic Sexism in Fantasy. Let's Unpack That.Document156 pagesHistorically Authentic Sexism in Fantasy. Let's Unpack That.titusgroanXXIINo ratings yet

- Emotional IntelligenceDocument4 pagesEmotional IntelligenceEmma Elena StroeNo ratings yet

- Aurat FoundationDocument29 pagesAurat FoundationSadia Shahid100% (1)

- Sociology MCQsDocument22 pagesSociology MCQs080801userNo ratings yet

- Women Can Be A Better Leader Than MenDocument8 pagesWomen Can Be A Better Leader Than MenJeffNo ratings yet

- Feminist Comm TheoriesDocument24 pagesFeminist Comm Theoriesjung수연No ratings yet

- Reading Habits Orignal DataDocument73 pagesReading Habits Orignal DataKrizna Dingding DotillosNo ratings yet

- Polls On Attitudes On Homosexuality & Gay MarriageDocument88 pagesPolls On Attitudes On Homosexuality & Gay MarriageAmerican Enterprise InstituteNo ratings yet

- Rticle: Describing Camp Talk: Language/pragmatics/politicsDocument21 pagesRticle: Describing Camp Talk: Language/pragmatics/politicsFernanda PôrtoNo ratings yet

- An Act Establishing A National Policy On Population, Creating The Commission On Population and For Other PurposesDocument3 pagesAn Act Establishing A National Policy On Population, Creating The Commission On Population and For Other PurposesNynn Juliana GumbaoNo ratings yet

- Mock Io Outline of Medea and ConceptionDocument18 pagesMock Io Outline of Medea and Conceptionapi-475699595No ratings yet

- The Laugh of The Medusa (Helene Cixous) - OUTLINEDocument1 pageThe Laugh of The Medusa (Helene Cixous) - OUTLINESweetverni AcesNo ratings yet

- Building Dialogue Between Citizens and The State: Six Factors Contributing To Change in The Within and Without The State Programme in DRCDocument12 pagesBuilding Dialogue Between Citizens and The State: Six Factors Contributing To Change in The Within and Without The State Programme in DRCOxfamNo ratings yet

- Thirumoolar Writings On GenderDocument3 pagesThirumoolar Writings On GenderSutharthanMariyappan0% (1)

- (Alternative Criminology) Beverly Yuen Thompson - Covered in Ink - Tattoos, Women and The Politics of The Body (2015, NYU Press) PDFDocument216 pages(Alternative Criminology) Beverly Yuen Thompson - Covered in Ink - Tattoos, Women and The Politics of The Body (2015, NYU Press) PDFmr T100% (1)

- Gen Ed Final PasarDocument15 pagesGen Ed Final PasarSofia Nicole SewaneNo ratings yet

- A Doll's House Essay - SchoolDocument3 pagesA Doll's House Essay - SchoolStewart ScreaighNo ratings yet

- Sociology 03122021Document22 pagesSociology 03122021Pramod SahuNo ratings yet

- El-Bushra Judy - Fused in Combat. Gender Relations and Armed ConfllictDocument394 pagesEl-Bushra Judy - Fused in Combat. Gender Relations and Armed ConfllictDiego Salcedo AvilaNo ratings yet

- 2 Report Sexual Identities in TransitDocument8 pages2 Report Sexual Identities in TransitSebastian GodlewskiNo ratings yet

- Mona GleasonDocument36 pagesMona GleasonrheaNo ratings yet

- Chap 4 PDFDocument87 pagesChap 4 PDFNgơTiênSinhNo ratings yet

- Queer Feminist Climate Justice GAARD PDFDocument10 pagesQueer Feminist Climate Justice GAARD PDFmrxNo ratings yet

- Sexual Harassment Complaint Against Superintendent of Schools David M. HealyDocument6 pagesSexual Harassment Complaint Against Superintendent of Schools David M. HealyAsbury Park PressNo ratings yet

- Tablica So Vsemi PozamiDocument20 pagesTablica So Vsemi PozamiДОБРЯЧОК САНЯNo ratings yet

- West Side Story - Music and Gender by Charles Richard FeasbyDocument51 pagesWest Side Story - Music and Gender by Charles Richard FeasbyCharlie Feasby100% (1)

- Maria Wyke - The Roman Mistress - Ancient and Modern Representations (2002) PDFDocument463 pagesMaria Wyke - The Roman Mistress - Ancient and Modern Representations (2002) PDFGuilherme PezzenteNo ratings yet

- TabulateDocument23 pagesTabulateJoanne WongNo ratings yet

- Jane Sturges Thesis 1996Document307 pagesJane Sturges Thesis 1996Ichigo NanaNo ratings yet