Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Migraine Headache

Uploaded by

Reem Al KelaniOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Migraine Headache

Uploaded by

Reem Al KelaniCopyright:

Available Formats

Migraine Headache

What is a migraine headache?

A migraine headache is a form of vascular headache. Migraine headache is caused by vasodilatation (enlargement of blood vessels) that causes the release of chemicals from nerve fibers that coil around the large arteries of the brain. Enlargement of these blood vessels stretches the nerves that coil around them and causes the nerves to release chemicals. The chemicals cause inflammation, pain, and further enlargement of the artery. The increasing enlargement of the arteries magnifies the pain. Migraine attacks commonly activate the sympathetic nervous system in the body. The sympathetic nervous system is often thought of as the part of the nervous system that controls primitive responses to stress and pain, the so-called "fight or flight" response, and this activation causes many of the symptoms associated with migraine attacks; for example, the increased sympathetic nervous activity in the intestine causes nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea.

Sympathetic activity also delays emptying of the stomach into the small intestine and thereby prevents oral medications from entering the intestine and being absorbed. The impaired absorption of oral medications is a common reason for the ineffectiveness of medications taken to treat migraine headaches. The increased sympathetic activity also decreases the circulation of blood, and this leads to pallor of the skin as well as cold hands and feet. The increased sympathetic activity also contributes to the sensitivity to light and sound sensitivity as well as blurred vision.

Migraine afflicts 28 million Americans, with females suffering more frequently (17%) than males (6%). Missed work and lost productivity from migraine create a significant public burden. Nevertheless, migraine still remains largely underdiagnosed and undertreated. Less than half of individuals with migraine are diagnosed by their doctors.

What are the symptoms of migraine headaches?

Migraine is a chronic condition with recurrent attacks. Most (but not all) migraine attacks are associated with headaches.

Migraine headaches usually are described as an intense, throbbing or pounding pain that involves one temple. (Sometimes the pain is located in the forehead, around the eye, or at the back of the head).

The pain usually is unilateral (on one side of the head), although about a third of the time the pain is bilateral (on both sides of the head). The unilateral headaches typically change sides from one attack to the next. (In fact, unilateral headaches that always occur on the same side should alert the doctor to consider a secondary headache, for example, one caused by a brain tumor). A migraine headache usually is aggravated by daily activities such as walking upstairs. Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, facial pallor, cold hands, cold feet, and sensitivity to light and sound commonly accompany migraine headaches. As a result of this sensitivity to light and sound, migraine sufferers usually prefer to lie in a quiet, dark room during an attack. A typical attack lasts between 4 and 72 hours.

An estimated 40%-60% of migraine attacks are preceded by premonitory (warning) symptoms lasting hours to days. The symptoms may include:

sleepiness, irritability, fatigue, depression or euphoria, yawning, and cravings for sweet or salty foods.

Patients and their family members usually know that when they observe these warning symptoms that a migraine attack is beginning.

Migraine aura

An estimated 20% of migraine headaches are associated with an aura. Usually, the aura precedes the headache, although occasionally it may occur simultaneously with the headache. The most common auras are:

1. flashing, brightly colored lights in a zigzag pattern (referred to as fortification spectra), usually starting in the middle of the visual field and progressing outward; and 2. a hole (scotoma) in the visual field, also known as a blind spot.

Some elderly migraine sufferers may experience only the visual aura without the headache. A less common aura consists of pins-and-needles sensations in the hand and the arm on one side of the body or pins-and-needles sensations around the mouth and the nose on the same side. Other auras include auditory (hearing) hallucinations and abnormal tastes and smells. For approximately 24 hours after a migraine attack, the migraine sufferer may feel drained of energy and may experience a low-grade headache along with sensitivity to light and sound. Unfortunately, some sufferers may have recurrences of the headache during this period.

What are some variants of migraine headaches?

Complicated migraines are migraines that are accompanied by neurological dysfunction. The part of the body that is affected by the dysfunction is determined by the part of the brain that is responsible for the headache. Vertebrobasilar migraines are characterized by dysfunction of the brainstem (the lower part of the brain that is responsible for automatic activities like consciousness and balance). The symptoms of vertebrobasilar migraines include:

fainting as an aura, vertigo (dizziness in which the environment seems to be spinning), and double vision.

Hemiplegic migraines are characterized by:

paralysis or weakness of one side of the body, mimicking a stroke.

The paralysis or weakness is usually temporary, but sometimes it can last for days. Retinal, or ocular, migraines are rare attacks characterized by repeated instances of scotomata (blind spots) or blindness on one side, lasting less than an hour, that can be associated with headache. Irreversible vision loss can be a complication of this rare form of migraine.

How is a migraine headache diagnosed?

Migraine headaches are usually diagnosed when the symptoms described previously are present. Migraine generally begins in childhood to early adulthood. While migraines can first occur in an individual beyond the age of fifty, advancing age makes other types of headaches more likely. A family history usually is present, suggesting a genetic predisposition in migraine sufferers. The examination of individuals with migraine attacks usually is normal. Patients with the first headache ever, worst headache ever, a significant change in the characteristics of headache or an association of the headache with nervous system symptoms, like visual or hearing or sensory loss, may require additional tests to exclude diseases other than migraine. The tests may include blood testing, brain scanning (either CT or MRI), and a spinal tap.

How are migraine headaches treated?

Treatment includes therapies that may or may not involve medications.

Non-medication therapies for migraine

Therapy that does not involve medications can provide symptomatic and preventative therapy.

Using ice, biofeedback, and relaxation techniques may be helpful in stopping an attack once it has started. Sleep may be the best medicine if it is possible.

Preventing migraine takes motivation for the patient to make some life changes. Patients are educated as to triggering factors that can be avoided. These triggers include:

smoking, and avoiding certain foods especially those high in tyramine such as sharp cheeses or those containing sulphites (wines) or nitrates (nuts, pressed meats).

Generally, leading a healthy life-style with good nutrition, an adequate intake of fluids, sufficient sleep and exercise may be useful. Acupuncture has been suggested to be a useful therapy.

Medication for migraine

Individuals with occasional mild migraine headaches that do not interfere with daily activities usually medicate themselves with over-the-counter (OTC or non-prescription) pain relievers (analgesics). Many OTC analgesics are available. OTC analgesics have been shown to be safe and effective for short-term relief of headache (as well as muscle aches, pains, menstrual cramps , and fever) when used according to the instructions on their labels.

There are two major classes of OTC analgesics:

acetaminophen (Tylenol), and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).

Acetaminophen Acetaminophen reduces pain and fever by acting on pain centers in the brain. Acetaminophen is well tolerated and generally is considered easier on the stomach than NSAIDs. However, acetaminophen can cause severe liver damage in high (toxic) doses or if used on a regular basis over extended periods of time. In individuals who regularly consume moderate or large amounts

of alcohol, acetaminophen can cause serious damage to the liver in lower doses that usually are not toxic. Acetaminophen also can damage the kidneys when taken in large doses. Therefore, acetaminophen should not be taken more frequently or in larger doses than recommended on the package label. NSAIDS The two types of NSAIDs are 1) aspirin and 2) non-aspirin. Examples of non-aspirin NSAIDs are ibuprofen (Advil, Nuprin, Motrin IB, and Medipren) and naproxen (Aleve). Some NSAIDs are available by prescription only. Prescription NSAIDs are usually prescribed to treat arthritis and other inflammatory conditions such as bursitis, tendonitis, etc. The difference between OTC and prescription NSAIDs usually is the amount of the active ingredient contained in each pill. For example, OTC naproxen (Aleve) contains 220 mg of naproxen per pill, whereas prescription naproxen (Naprosyn) contains 375 or 500 mg of naproxen per pill. NSAIDs relieve pain by reducing the inflammation that causes the pain (they are called nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs or NSAIDs because they are different from corticosteroids such as prednisone, prednisolone, and cortisone which also reduce inflammation). Corticosteroids, though valuable in reducing inflammation, have predictable and potentially serious side effects, especially when used long-term. Their full effects also require hours or days. NSAIDs do not have the same side effects that corticosteroids have and their onset of action is faster. Aspirin, Aleve, Motrin, and Advil all are NSAIDs and are similarly effective in relieving pain and fever. The main difference between aspirin and non-aspirin NSAIDs is their effect on platelets, the small particles in blood that cause blood clots to form. Aspirin prevents the platelets from forming blood clots. Therefore, aspirin can increase bleeding by preventing blood from clotting though it also can be used therapeutically to prevent clots from causing heart attacks and strokes. The non-aspirin NSAIDs also have antiplatelet effects, but their antiplatelet action does not last as long as aspirin, i.e. hours rather than days. Aspirin, acetaminophen, and caffeine also are available combined in OTC analgesics for the treatment of headaches including migraine. Examples of such combination analgesics are Painaid, Excedrin, Fioricet, and Fiorinal. Finding an effective analgesic or analgesic combination often is a process of trial and error because individuals respond differently to different analgesics. In general, a person should use the analgesic that has worked in the past. This will increase the likelihood that an analgesic will be effective and decrease the risk of side effects. There are several precautions that should be observed with OTC analgesics:

Children and teenagers should not use aspirin for the treatment of headaches, other pain, or fever, because of the risk of developing Reye's Syndrome, a life-threatening neurological disease that can lead to coma and even death. People with balance disorders or hearing difficulties should avoid using aspirin because aspirin may aggravate these conditions.

People taking blood thinners such as warfarin (Coumadin) should not take aspirin and nonaspirin NSAIDs without a doctor's supervision because they add further to the risk of bleeding that is caused by the blood thinner. People with active ulcers of the stomach and duodenum should not take aspirin and nonaspirin NSAIDs because they can increase the risk of bleeding from the ulcer and impair healing of the ulcer. People with advanced liver disease should not take aspirin and non-aspirin NSAIDs because they may impair kidney function. Deterioration of kidney function in these patients can lead to failure of the kidneys. OTC or prescription analgesics should not be overused. Overuse of analgesics can lead to the development of tolerance (increasing ineffectiveness of the analgesic) and rebound headaches (return of the headache as soon as the effect of the analgesic wears off, usually in the early morning hours). Thus, overuse of analgesics can lead to a vicious cycle of more and more analgesics for headaches that respond less and less to treatment.

What other medications are used for treating migraine headaches?

Narcotics and butalbital-containing medications sometimes are used to treat migraine headaches; however, these medications are potentially addicting and are not used as initial treatment. They are sometimes used for individuals whose headaches fail to respond to OTC medications but who are not candidates for triptans either due to pregnancy or the risk of heart attack and stroke. In migraine sufferers with severe nausea, a combination of a triptan and an antinausea medication, for example, prochlorperazine (Compazine) or metoclopramide (Reglan) may be used. When nausea is severe enough that oral medications are impractical, intravenous medications such as DHE-45 (dihydroergotamine), prochlorperazine (Compazine), and valproate (Depacon) are useful.

How are migraine headaches prevented?

There are two ways to prevent migraine headaches: 1) by avoiding factors ("triggers") that cause the headaches, and 2) by preventing headaches with medications (prophylactic medications). Neither of these preventive strategies is 100% effective. The best one can hope for is to reduce the frequency of headaches.

What are migraine triggers?

A migraine trigger is any environmental or physiological factor that leads to a headache in individuals who are prone to develop headaches. Only a small proportion of migraine sufferers, however, clearly can identify triggers. Examples of triggers include:

stress, sleep disturbances, fasting,

hormones, bright or flickering lights, odors, cigarette smoke, alcohol, aged cheeses, chocolate, monosodium glutamate, nitrites, aspartame, and caffeine.

For some women, the decline in the blood level of estrogen during the onset of menstruation is a trigger for migraine headaches (sometimes referred to as menstrual migraines). The interval between exposure to a trigger and the onset of headache varies from hours to two days. Exposure to a trigger does not always lead to a headache. Conversely, avoidance of triggers cannot completely prevent headaches. Different migraine sufferers respond to different triggers, and any one trigger will not induce a headache in every person who has migraine headaches.

Sleep and migraine

Disturbances such as sleep deprivation, too much sleep, poor quality of sleep, and frequent awakening at night are associated with both migraine and tension headaches, whereas improved sleep habits have been shown to reduce the frequency of migraine headaches. Sleep also has been reported to shorten the duration of migraine headaches.

Fasting and migraine

Fasting possibly may precipitate migraine headaches by causing the release of stress-related hormones and lowering blood sugar. Therefore, migraine sufferers should avoid prolonged fasting.

Bright lights and migraine

Bright lights and other high intensity visual stimuli can cause headaches in healthy subjects as well as patients with migraine headaches, but migraine people who suffer from migraines seem to have a lower than normal threshold for light-induced headache pain. Sunlight, television, and flashing lights all have been reported to precipitate migraine headaches.

Caffeine and migraine

Caffeine is contained in many food products (cola, tea, chocolates, coffee) and OTC analgesics. Caffeine in low doses can increase alertness and energy, but caffeine in high doses can cause insomnia, irritability, anxiety, and headaches. The over-use of caffeine-containing analgesics causes rebound headaches. Furthermore, individuals who consume high levels of caffeine regularly are more prone to develop withdrawal headaches when caffeine is stopped abruptly.

Female hormones and migraine

Some women who suffer from migraine headaches experience more headaches around the time of their menstrual periods. Other women experience migraine headaches only during the menstrual period. The term "menstrual migraine" is used mainly to describe migraines that occur in women who have almost all of their headaches from two days before to one day after their menstrual periods. Declining levels of estrogen at the onset of menses is likely to be the cause of menstrual migraines. Decreasing levels of estrogen also may be the cause of migraine headaches that develop among users of birth control pills during the week that estrogens are not taken.

What should migraine sufferers do?

Individuals with mild and infrequent migraine headaches that do not cause disability may require only OTC analgesics. Individuals who experience several moderate or severe migraine headaches per month or whose headaches do not respond readily to medications should avoid triggers and consider modifications of their lifestyle. Lifestyle modifications for migraine sufferers include:

Go to sleep and wake up at the same time each day. Exercise regularly (daily if possible). Make a commitment to exercise even when traveling or during busy periods at work. Exercise can improve the quality of sleep and reduce the frequency and severity of migraine headaches. Build up your exercise level gradually. Overexertion, especially for someone who is out of shape, can lead to migraine headaches. Do not skip meals, and avoid prolonged fasting. Limit stress through regular exercise and relaxation techniques. Limit caffeine consumption to less than two caffeine-containing beverages a day. Avoid bright or flashing lights and wear sunglasses if sunlight is a trigger. Identify and avoid foods that trigger headaches by keeping a headache and food diary. Review the diary with your doctor. It is impractical to adopt a diet that avoids all known migraine triggers; however, it is reasonable to avoid foods that consistently trigger migraine headaches.

What are prophylactic medications for migraine headaches?

Prophylactic medications are medications taken daily to reduce the frequency and duration of migraine headaches. They are not taken once a headache has begun. There are several classes of prophylactic medications:

beta blockers, calcium-channel blockers, tricyclic antidepressants, antiserotonin agents, and anticonvulsants.

Medications with the longest history of use are propranolol (Inderal), a beta blocker, and amitriptyline (Elavil, Endep), an antidepressant. When choosing a prophylactic medication for a patient the doctor must take into account side effects of the drug, drug-drug interactions, and coexisting conditions such as diabetes, heart disease, and high blood pressure. Who should consider prophylactic medications to prevent migraine headaches? Not all migraine sufferers need prophylactic medications; individuals with mild or infrequent headaches that respond readily to abortive medications do not need prophylactic medications. Individuals who should consider prophylactic medications are those who:

1. Require abortive medications for migraine headaches more frequently than twice weekly. 2. Have two or more migraine headaches a month that do not respond readily to abortive medications. 3. Have migraine headaches that are interfering substantially with their quality of life and work. 4. Cannot take abortive medications because of heart disease, stroke, or pregnancy, or cannot tolerate abortive medications because of side effects.

How effective are prophylactic medications? Prophylactic medications can reduce the frequency and duration of migraine headaches but cannot be expected to eliminate migraine headaches completely. The success rate of most prophylactic medications is approximately 50%. Success in preventing migraine headaches is defined as more than a 50% reduction in the frequency of headaches. Prophylactic medications usually are begun at a low dose that is increased slowly in order to minimize side effects. Individuals may not notice a reduction in the frequency, severity, or duration of their headaches for 2 to 3 months after starting treatment.

What is the proper way to use preventive medications?

Doctors familiar with the treatment of migraine headaches should prescribe preventive medications.

Decisions about which preventive medication to use are based on the side effects of the medication and the presence of any medical conditions. Propranolol (Inderal) often is used first, provided that the individual does not have asthma, COPD, or heart disease. Amitriptyline (Elavil, Endep) also is used commonly. Preventive medications are begun at low doses and gradually increased to higher doses if needed. This minimizes side effects from the medications. Preventive medications are to be taken daily for months to years. When they are stopped, the dose needs to be gradually reduced rather than abruptly stopped. Abruptly stopping preventive medications can lead to headaches. In some instances, more than one drug may be needed. Non-medication and behavioral therapies also may be needed.

You might also like

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5795)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1091)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Flexin Marketing ReportDocument68 pagesFlexin Marketing ReportHammad BukhariNo ratings yet

- DepakoteDocument5 pagesDepakotejNo ratings yet

- Potpourri of Healing SecretsDocument11 pagesPotpourri of Healing SecretsSamee's Music100% (3)

- Homework A1Document5 pagesHomework A1yellowfish31303No ratings yet

- StrokeDocument9 pagesStrokeezar Al barraqNo ratings yet

- VDVDocument5 pagesVDVVenkatesan VidhyaNo ratings yet

- Aspirin in Episodic Tension-Type Headache: Placebo-Controlled Dose-Ranging Comparison With ParacetamolDocument9 pagesAspirin in Episodic Tension-Type Headache: Placebo-Controlled Dose-Ranging Comparison With ParacetamolErwin Aritama IsmailNo ratings yet

- Laporan Kasus SolDocument32 pagesLaporan Kasus SolameliaNo ratings yet

- Model Paper 4Document22 pagesModel Paper 4Mobin Ur Rehman KhanNo ratings yet

- Formative Test I NBSS 2021-2022 - Attempt ReviewDocument30 pagesFormative Test I NBSS 2021-2022 - Attempt ReviewAlif YusufNo ratings yet

- The Efficacy of Venlafaxine, Flunarizine, and Valproic Acid in The Prophylaxis of Vestibular MigraineDocument5 pagesThe Efficacy of Venlafaxine, Flunarizine, and Valproic Acid in The Prophylaxis of Vestibular MigraineagustianaNo ratings yet

- Nat Prog Book 1 PDFDocument430 pagesNat Prog Book 1 PDFIoana Brăteanu100% (1)

- PANRE and PANCE Review Emergency MedicineDocument15 pagesPANRE and PANCE Review Emergency MedicineThe Physician Assistant Life100% (2)

- Cva 1Document42 pagesCva 1ياسر كوثر هانيNo ratings yet

- Second Partial: Technical University of AmbatoDocument70 pagesSecond Partial: Technical University of AmbatoEdgar MartinezNo ratings yet

- A Brief Materia Medica of Some Lesser-Known NosodesDocument103 pagesA Brief Materia Medica of Some Lesser-Known NosodesnitkolNo ratings yet

- Pyrosid CapsuleDocument3 pagesPyrosid Capsulehk_scribdNo ratings yet

- Herbs and Formulas That Release The ExteriorDocument41 pagesHerbs and Formulas That Release The ExteriorFrancisco VilaróNo ratings yet

- Quick Code ListDocument18 pagesQuick Code Listsjjhala100% (4)

- Medical Record Summary Template (Disability)Document17 pagesMedical Record Summary Template (Disability)Alipit Jr. D. ArmanNo ratings yet

- This Patient Have A Hemorrhagic StrokeDocument7 pagesThis Patient Have A Hemorrhagic StrokeMario ARNo ratings yet

- Neuro 4 - QuestionsDocument50 pagesNeuro 4 - Questionskim100% (1)

- Clinical Case Scenarios Slide Set Powerpoint 2183787181Document58 pagesClinical Case Scenarios Slide Set Powerpoint 2183787181saheefaNo ratings yet

- Headache History TakingDocument6 pagesHeadache History TakingParsaant SinghNo ratings yet

- Mollah MD Foysal - MALE - 21 Yrs +918867572813 AHJN.0000204829 2306447Document3 pagesMollah MD Foysal - MALE - 21 Yrs +918867572813 AHJN.0000204829 2306447Adyan FoysalNo ratings yet

- Talley & O'Connor Quiz SampleDocument5 pagesTalley & O'Connor Quiz SamplefilchibuffNo ratings yet

- MeningiomaDocument7 pagesMeningiomadrhendyjuniorNo ratings yet

- Space Occupying LesionDocument10 pagesSpace Occupying LesionAnna Moser100% (1)

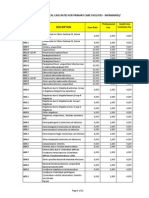

- PhilHealth Circular No. 0035, s.2013 Annex 5 List of Medical Case Rates For Primary Care FacilitiesDocument22 pagesPhilHealth Circular No. 0035, s.2013 Annex 5 List of Medical Case Rates For Primary Care FacilitiesChrysanthus HerreraNo ratings yet

- Acupressure Points For Brain StimulationDocument9 pagesAcupressure Points For Brain Stimulationلوليتا وردةNo ratings yet