Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Original: Appellants' Reply Brief

Uploaded by

Finally Home RescueOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Original: Appellants' Reply Brief

Uploaded by

Finally Home RescueCopyright:

Available Formats

NO.

65365-2

IN THE COURT OF APPEALS

OF THE STATE OF WASHINGTON,

DIVISION ONE

VULCAN INC., a Washington corporation, VULCAN CAPITAL

PRIVATE EQUITY, INC., a Delaware corporation, and VCPE ORANGE

II, LLC, a Delaware limited liability company,

Appellants,

v.

DAVID CAPOBIANCO, an individual, and NAVIN THUKKARAM, an

individual,

Respondents.

APPELLANTS' REPLY BRIEF

Stephen C. Willey, WSBA

Miles A. Yanick, WSBA

SAVITT BRUCE & WILLEY

1325 Fourth Avenue, Suite 14101""')

Seattle, W A 98101

(206) 749-0500 ':;i

.

Attorneys for Appellants }'

ORIGINAL

",

\-'

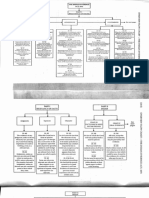

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

I. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................... 1

II. ARGUMENT AND AUTHORITy ................................................ 3

A. RESPONDENTS MISSTATE THE APPLICABLE

STANDARD OF REVIEW ................................................ 3

B. THE TRIAL COURT FAILED TO CONDUCT THE

STATUTORILY REQUIRED REVIEW ........................... 4

1. FIRST OPTIONS HAS NO RELEVANCE

TO THIS CASE BECAUSE THE

STATUTORY GROUNDS FOR

VACATUR CANNOT BE CONTRACTED

OUT TO ARBITRATORS ..................................... 5

2. THERE IS NO EVIDENCE THAT THE

PARTIES INTENDED TO SUBMIT THE

ISSUE OF VACATUR TO

ARBITRATION ..................................................... 7

3. NO CASE-INCLUDING FIRST

OPTIONS-HOLDS THAT SUBMITTING

THE ISSUE OF DISQUALIFICATION TO

ARBITRATION EFFECTIVELY WAIVES

SUBSEQUENT JUDICIAL REVIEW FOR

EVIDENT PARTIALITY OR

PREJUDICIAL MISBEHAVIOR .......................... 9

C. VACATUR IS REQUIRED BECAUSE THE RECORD

SHOWS EXTENSIVE, MERITS-BASED, EX PARTE

CONTACTS WITH MR. HARRIGAN ............................ 12

1. MR. HARRIGAN'S INVOICES

UNDENIABLY DOCUMENT EX PARTE

DISCUSSIONS ABOUT THE MERITS OF

THE CASE ............................................................ 12

-1-

,

2. THE TRIAL COURT ERRED BY GIVING

CONCLUSIVE EFFECT TO AN

INCOMPLETE, SELF-SERVING, NON-

RECORD DECLARATION FROM

RESPONDENTS' COUNSEL. ............................. 15

3. THE TRIAL COURT ERRED BY

RENDERING JUDGMENT WITHOUT

HOLDING AN EVIDENTIARY

HEARING OR ALLOWING DISCOVERy ........ 16

D. MR. HARRIGAN'S FAILURE TO DISCLOSE HIS EX

PARTE COMMUNICATIONS CREATES A

REASONABLE IMPRESSION OF PARTIALITy ......... 18

E. VULCAN DID NOT WAIVE ITS RIGHTS TO

CHALLENGE MR. HARRIGAN'S MISCONDUCT ..... 19

F. VACATUR IS ALSO REQUIRED BECAUSE THE

ARBITRATORS EXCEEDED THEIR POWERS ........... 21

1. THE PANEL AWARDED

RESPONDENTS A REMEDY FOR A

BREACH ONLY "AS TO" OTHER

EMPLOYEES ....................................................... 22

2. THE PANEL GROSSLY MISAPPLIED

THE IMPLIED COVENANT TO AWARD

RESPONDENTS A BENEFIT THEY

SOUGHT BUT FAILED TO GAIN

DURING NEGOTIATIONS ................................ 24

V. CONCLUSION ............................................................................. 25

-11-

..

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases

Beebe Med. Ctr., Inc. v. InSight Health Services Corp., 751 A.2d 426

(Del. Ch. 1999) ..................................................................................... 10

Boyhan v. Maguire, 693 So.2d 659 (Fl. 1997) .......................................... 10

Britz, Inc. v. Alfa-Laval Food & Dairy Co., 34 Cal. App. 4th 1085, 1102

(1995) .................................................................................................... 10

Butler v. Craft Eng. Const. Co., Inc., 67 Wn.App. 684,691 (1992) .......... 4

Corporate Property Assocs. 14 Inc. v. CHR Holding Corp., 2008 Del. Ch.

LEXIS 45 (Del. Ch. April 10, 2008) ..................................................... 24

Cytec Corp. v. Deka Prods. Ltd. Partnership, 439 F.3d 27 (1 st Cir. 2006) 3

Fidelity Federal Bank v. Durga Ma Corp., 386 F.3d 1306 (9

th

Cir. 2004)

........................................................................................................ 20,21

First Options o/Chicago, Inc. v. Kaplan, 514 U.S. 938 (1995) ........ passim

Health Servs. Mgmt. Corp. v. Huges, 975 F.2d 1253 (7

th

Cir. 1992) ....... 10

Hoeft v. MVL Group, Inc., 343 F.3d 57 (2

nd

Cir. 2003) .......................... 2,5

In re Estate o/Nelson, 85 Wn.2d 602,605-06 (1975) ................................ 4

Nationwide Mut. Ins. Co. v. Home Insurance, 278 F.3d 621 (6

th

Cir. 2002)

.............................................................................................................. 19

New Regency Productions, Inc. v. Nippon Herald Films, Inc., 501 F.3d

1101 (9th Cir. 2007) .............................................................................. 18

Reeves Bros., Inc. v. Capital-Mercury Shirt Corp., 962 F. Supp. 408

(S.D.N.Y. 1997) .................................................................................... 10

Sanko s.s. Co. v. Cook Indus., 495 F.2d 1260 (2

nd

Cir. 1973) ................. 17

Schmitz v. Zilveti, 20 F.3d 1043 (9

th

Cir. 1994) .................................... 3, 18

-111-

'II

Superior Vision Services, Inc. v. Liastar Life Ins. Co., 2006 Del. Ch.

LEXIS 160 (Del. Ch. August 25, 2006) ............................................... 24

Totem Marine Tug & Barge, Inc. v. N. Am. Towing, Inc., 607 F .2d 649

(5th Cir. 1979) ....................................................................................... 12

Univ. Commons-Urbana, Ltd. v. Universal Const., Inc., 304 F.3d 1331

(11th Cir. 2002) ..................................................................................... 17

Washington State Physicians Ins. Exchange & Ass'n v. Fisons Corp., 122

Wn.2d 299 (1993) .................................................................. : .............. 20

Williams v. NFL, 582 F.3d 863 (8

th

Cir. 2009) ......................................... 19

Statutes

9 U.S.C. 9 ................................................................................................. 7

9 U.S.C. 10 ....................................................................................... 4,5, 7

9 U.S.C. 10(a) ................................................................................. passim

9 U.S.C. 10(a)(2) .................................................................... 1,2,4,9, 18

9 U.S.C. 10(a)(3) .......................................................................... 1,2,4,9

9 U.S.C. 10(a)(4) ............................................................................ 2, 7,22

Other Authorities

AAA Code of Ethics, Canon II(D) ........................................................... 20

AAA Code of Ethics, Canon 111. ............................................................... 13

AAA Rule R-I7(a) .................................................................................. 7,8

AAA Rule R-18(a) ........................................................................ 12, 13,20

AAA Rule R-46 .......................................................................................... 8

-IV-

..

I. INTRODUCTION

The Arbitration Award in this case should be vacated under 10(a)

of the Federal Arbitration Act ("FAA") on any of three separate grounds.

First, the undisputed law and facts here make clear that the Award

was tainted by evident partiality and prejudicial misconduct under

10(a)(2)-(3). As to the law, Respondents do not and cannot dispute that ex

parte discussion of the merits with an arbitrator-in the selection process

or any other time-is improper. As to the facts, Respondents do not and

cannot dispute that they (1) provided copies of their draft pleading to an

arbitrator candidate, and had ex parte discussions regarding the same; (2)

submitted case evidence ex parte to the arbitrator; and (3) engaged in ex

parte discussions with the arbitrator regarding factual issues. Neither

Respondents nor the trial court has ever even attempted to articulate how

these communications are not merits-based. At a minimum, these facts

necessarily raise serious questions about the undisputed ex parte contacts,

which must be resolved through evidentiary examination.

Second, where an arbitrator has had such ex parte discussions with

a party, he or she must disclose them. Mr. Harrigan's failure to do so is

prima facie evidence creating a "reasonable impression of partiality."

Recognizing that an independent review of the facts would

necessarily lead to at least a prima facie finding of evident partiality (and

-1-

with no countervailing record evidence), Respondents contend that courts

are disabled from performing the required statutory review because the

parties here somehow transferred that task to Judge Lukens (and, thus,

waived the right to independent judicial review). But they cannot cite a

single case supporting either their contention that parties can contract

away a court's review obligations under the FAA or their argument that a

routine agreement to have private adjudicators resolve arbitrator

disqualification somehow bars judicial review of an award on the separate

question of vacatur under 1O(a)(2)-(3).

As a result, Respondents' consistent theme of "deference" is beside

the point. Review of arbitration awards is deferential only insofar as the

grounds for judicial vacatur are limited. But in examining the issues that

the FAA does identify as grounds for vacatur, there is no deference due

the arbitrator. This basic tenet is particularly important where, as here, the

challenge goes to the integrity and impartiality of the arbitration itself.

The FAA's statutorily enumerated grounds establish the "floor for judicial

review" below which courts cannot-even with the parties' consent-

descend. Hoeft v. MVL Group, Inc., 343 F.3d 57,64 (2d Cir. 2003).

Third, the Award must be vacated under 1O(a)(4) because the

Panel exceeded its powers when it rendered an award that provides relief

for a (supposed) breach of contract to persons who concededly did not

-2-

suffer any damages due to the breach. The law does not allow a breach as

to John to enable relief as to Mary. The Arbitration Award nonetheless

does just that. The Panel held that Vulcan breached the VEC Agreement

not as to Respondents but as to certain other Vulcan employees. And yet

it gave relief to Respondents for this breach. It did so proclaiming that the

doctrine of good faith and fair dealing allowed it to invent a remedy for

Respondents by implying terms that are flatly contradicted by both the

terms of the parties' contract and what the parties discussed in their

negotiations. Such a remedy disregarded binding Delaware law, which

holds that the doctrine of good faith and fair dealing may not be used to

imply contract terms unless it is absolutely clear that the parties would

have agreed to such terms had they thought to negotiate them.

II. ARGUMENT AND AUTHORITY

A. RESPONDENTS MISSTATE THE APPLICABLE

STANDARD OF REVIEW

This Court's review is de novo regarding the application oflaw

and the relevant facts. This is true under federal law and Washington law.

"In an action to vacate or confirm an arbitral award, we typically

review the district court's decision de novo," and "[t]his remains true

whether the arbitrators' apparent error concerns a matter of law or a matter

offact." Cytec Corp. v. Deka Prods. Ltd. Partnership, 439 F.3d 27,32 (18t

Cir. 2006); see also Schmitz v. Zilveti, 20 F.3d 1043, 1045 (9

th

Cir. 1994)

-3-

("Appellants question (1) the legal standard employed by the district court

and (2) the application of that legal standard to facts. This court reviews

both issues de novo."). Washington courts also hold that appellate review

of a trial court's decision is de novo, for both legal conclusions and factual

findings, where the decision is based on documentary submissions only

and there is no evidentiary hearing with live testimony. In re Estate of

Nelson, 85 Wn.2d 602,605-06 (1975); Butler v. Craft Eng. Const. Co.,

Inc., 67 Wn.App. 684, 691 (1992).

B. THE TRIAL COURT FAILED TO CONDUCT THE

STATUTORILY REQUIRED REVIEW

Respondents' central argument is as follows: where a party in

arbitration brings a motion to disqualify an arbitrator based on conduct

that indicates partiality and the motion is denied, then a trial court may not

vacate the subsequent arbitration award under 1O(a)(2) - (3) unless it

first (1) engages in an independent review of the disqualification decision,

and (2) independently vacates that decision, separate and apart from the

arbitration award, under 10. See, e.g., Resp. Br. at 21-29. But nothing

in logic or case law supports the notion that courts are powerless to vacate

awards tainted by evident partiality or misconduct merely because the

parties have followed an interim procedure to disqualify arbitrators.

Respondents' attempt to enlist the Supreme Court's decision in

First Options of Chicago, Inc. v. Kaplan, 514 U.S. 938 (1995), in their

--4-

supports fails for two independent reasons. For one, First Options had

nothing to do with whether parties can permissibly delegate to an

arbitrator the judicial function of reviewing awards under 10 of the

FAA, and every case cited to this Court holds, without exception, that

courts must perform this function. Secondly, even if the law permitted

delegation of this judicial function, all agree that it would require the

parties' manifest intent. Here, the parties manifested the opposite intent.

Further, every case to address the issue holds that agreeing to a process for

arbitrator disqualification in no way affects a party's right to judicial

review of an arbitration award under the FAA.

1. First Options has no relevance to this case

because the statutory grounds for vacatur cannot

be contracted out to arbitrators.

Nothing in the FAA and no case applying it holds or even suggests

that the courts' statutory duty to review arbitration awards and to vacate

them where the 10 safeguards have been breached can be abdicated by a

court or limited by contract. See Hoeft v. MVL Group, Inc., 343 F.3d 57,

64 (2

nd

Cir. 2003) ("Since federal courts are not rubber stamps, parties

may not, by private agreement, relieve them of their obligation to review

arbitration awards for compliance with IO(a)."). Simply put, IO(a) of

the FAA may not be contracted away.

Respondents offer no authority holding otherwise. Indeed, First

-5-

Options does not so much as touch upon the question of whether an

arbitrator could be delegated the courts' job in enforcing the statutory

grounds for vacating an arbitration award. While First Options may be of

note in clarifying the determination of who (a court or an arbitrator)

decides the threshold question of arbitrability, the foundational rule the

Court applies-and which Respondents tout-is unremarkable: arbitration

is a matter of contract and, therefore, the parties' intent. Thus, "the

question 'who has the primary power to. decide arbitrability' turns upon

what the parties agreed about that matter." 514 U.S. at 943.

But the fact that parties may submit to private arbitrators matters

on which the FAA is silent in no way supports the proposition advanced

by Respondents and rejected by every case to have addressed the issue:

that parties may contractually limit the courts' duty to vacate awards on

the enumerated grounds. The trial court missed this key distinction

between issues that the FAA directs courts to decide (which cannot be

delegated) and the world of other disputed issues (which can).!

1 Respondents attempt to muddle this patent distinction by citing IO(a)(4), which

provides for vacatur if an arbitrator "exceeded [his] powers." They argue that, under

First Options, parties can effectively delegate that issue to arbitrators by permitting them

to decide which issues are arbitrable. But if parties do agree to have an arbitrator decide

arbitrability, then the arbitrator who does so is not "exceed[ing]" his powers. Nothing in

First Options suggests that, in such a case, a party could not seek to vacate the award

under IO(a)(4), including review of whether the arbitrator "exceeded [his] powers."

-6-

2. There is no evidence that the parties intended to

submit the issue of vacatur to arbitration.

Even if First Options were relevant here, the question would be

whether the parties had expressly agreed to submit to Judge Lukens the

issue of whether to vacate the Arbitration A ward under the FAA for

"evident partiality" or "prejudicial misbehavior." Resp. Br. at 19.

Plainly they did not. As an initial matter, the parties' agreement to

arbitrate expressly contemplates that any arbitration award will be subject

to judicial review (i.e., pursuant to 9, 10 of the FAA). CP 183-84 at

10.8, 10.9. No subsequent agreement between the parties ever changed

that. This includes the parties' Arbitration Protocol, in which they agreed

to allow "a neutral third party [to] determine whether [ a] challenged

arbitrator shall be disqualified" under AAA Rule R-17(a), not whether any

award should be vacated under 10(a). CP 133 at N. Nowhere does

the Protocol address or refer to the subject of judicial review of any award,

much less contract away any party's right to seek vacatur. CP 132-36; cf

CP 373 (subsequent Confidentiality Agreement providing that a motion to

confirm or vacate could be brought in any court of competent jurisdiction).

Far from agreeing to submit the issue of vacatur to arbitration, the

parties expressly agreed not to. Under the Arbitration Protocol, AAA

Rule R-46 applied to the arbitration proceeding and this rule prohibits

arbitrators from vacating an award. Vulcan noted this fact when it first

-7-

objected to Mr. Harrigan's undisclosed ex parte contacts:

[U]nder AAA Rule R-46, ... the Panel is "not

empowered to redetennine the merits of any claim

already decided." ... The Superior Court is the

tribunal with jurisdiction to address the vacation of

the Award[.]

CP 380 (emphasis supplied.) Respondents never took issue with this

statement. Nor did Judge Lukens purport to exercise such jurisdiction,

stating that "[t]he sole issue presented [to him] for decision [wa]s whether

one of the party-appointed arbitrators in the underlying action should be

disqualified under Rule 17(a)[.]" CP 44? In sum, whether the Award was

subject to vacatur under any of the grounds set out in 1 O( a) was

expressly reserved for the Superior Court.

Respondents cannot dispute these facts. Instead, they strain to

conflate and confuse the issues. They argue that Vulcan "urged the trial

court to 'independently assess the merits of the disqualification issue.'"

Resp. Br. at 11,20 (emphasis supplied). But they neglect to mention that

the quote is from the trial court's order, which misstates Vulcan's position:

Vulcan never asked the trial court to review the "disqualification issue"

under any standard. Similarly, Respondents suggest that "the parties

2 Judge Lukens not only did not decide whether to vacate the award; he also applied

a different standard. While vacatur is required in instances of evident partiality, Judge

Lukens concluded that "Rule 17(a) requires a finding of partiality, not merely an

appearance of partiality" and "I cannot make that finding on the record before me." CP

48. Contrary to Respondents' suggestion (e.g., Resp. Briefat I), there was no evidentiary

hearing before Judge Lukens.

-8-

agreed to submit allegations of arbitrator partiality to arbitration." Resp.

Br. at 22. This vague overstatement misleadingly suggests that the parties

agreed to arbitrate the issues of evident partiality or misconduct under

1O(a)(2) - (3) of the FAA.

3

Without these semantic sleights of hand,

Respondents have no argument; the parties never agreed to arbitrate

Vulcan's rights under the FAA.

3. No case-including First Options-holds that

submitting the issue of disqualification to

arbitration effectively waives subsequent judicial

review for evident partiality or prejudicial

misbehavior.

The only evidence that Respondents even contend reflects an intent

to empower Judge Lukens to determine whether the Arbitration Award

should be vacated is the parties' agreement (in the Arbitration Protocol)

regarding arbitrator disqualification. But common sense and uniform case

law establish that agreeing to a process for resolving arbitrator

disqualification does not waive independent judicial review of a final

award for evident partiality or misconduct. No case suggests otherwise.

If there were cases supporting their position, surely Respondents

would have cited them. But First Options has never been read to mean, as

Respondents argue, that a disqualification decision made in an arbitration

3 Respondents know better. Elsewhere, they describe the parties' actual agreement.

Resp. Br. at 19 (the parties did "express[] their intent to arbitrate a particular issue or

grievance related to the arbitration itself' - i.e., "the issue of arbitrator disqualification.")

-9-

proceeding must itself be vacated under 10(a) before a court may vacate

the final award for evident partiality. Every case cited to this Court

involving such circumstances holds the opposite: a party does "not waive

its right to seek an independent ruling by the court on its-post-arbitration,

evident partiality claim" merely by agreeing to a procedure for resolution

of disqualification motions. Beebe Med. Ctr., Inc. v. InSight Health

Services Corp., 751 A.2d 426,440 (Del. Ch. 1999).4

Because they have no cases of their own to cite, Respondents' only

answer is to try to distinguish these authorities on the basis that they

involved resolution of disqualification motions before an AAA special

committee, while this case involves resolution of a disqualification motion

before Judge Lukens.

5

But that is a distinction without a difference. The

holding and rationale in all these cases is that interim disqualification

4 Accord Reeves Bros., Inc. v. Capital-Mercury Shirt Corp., 962 F. Supp. 408,413-

15 (S.D.N.Y. 1997); Boyhan v. Maguire, 693 So.2d 659,662 (FI. 1997); Britz, Inc. v.

Alfa-Laval Food & Dairy Co., 34 Cal. App. '4th 1085, 1102 (1995); Health Servs. Mgmt.

Corp. v. Hughes, 975 F.2d 1253, 1263 (7th Cir. 1992).

5 Respondents are wrong in their suggestion that the exercise of independent judicial

review in Beebe was based on the fact that the AAA had not produced a record

supporting its denial of the earlier disqualification motion. After concluding that a party

does not waive the right to independent judicial review by agreeing to a disqualification

process, the court went on to say, in the alternative, that the AAA's decision in that case

could not "withstand even the deferential scrutiny given to arbitration awards" because it

did not hold a hearing on the motion. 751 A.2d at 441. Instead, the AAA "adopt[ ed]

wholesale the view of the facts advocated by one of the parties' attorneys." Id. at 442.

That is exactly what Judge Lukens did in this case, by bizarrely deciding that "th[ e]

factual recitation [provided by Yarmuth, Respondents' counsel] must be considered as a

verity." CP 46. Even Beebe's alternative holding supports Vulcan.

-10-

procedures are different from, and do not waive or limit, subsequent

judicial review for partiality-which is equally true whether the private

disqualification panel is an AAA special committee or some other private

arbitrator. This is particularly true here, where Respondents concede the

sole reason for the provision in the Arbitration Protocol referring

disqualification decisions to a neutral third party was to "address[]

functions that would otherwise have been performed by the AAA." CP

4:22-23. Simply put, Judge Lukens took the place of the AAA; there is no

reason to treat him differently.

Beyond the evidence and the applicable law, the trial court never

considered the dispositive threshold issue of whether the parties intended

to empower Judge Lukens to resolve the question of vacatur. Apparently

misled by Respondents' rhetoric, the court considered only whether Judge

Lukens' decision constituted a separate "award." CP 580-81. Having

(incorrectly) determined that the Lukens Decision was a separate "award,"

the court concluded that it was required to "defer" to it, thus evading its

obligation to review the Arbitration Award under lO(a). As

Respondents now concede, such labels are irrelevant-the parties' intent is

what matters. Resp. Br. 24-25. Because the court never addressed this

issue, its decision cannot be affirmed.

-11-

C. VACATUR IS REQUIRED BECAUSE THE RECORD

SHOWS EXTENSIVE, MERITS-BASED, EX PARTE

CONTACTS WITH MR. HARRIGAN

The undisputed law and facts demonstrate partiality and

misconduct-and the trial court's legal error. Respondents concede the

law: Ex parte communications with an arbitrator about the merits of a

dispute are impermissible. And the record evidence-the invoices from

Mr. Harrigan and Respondents' counsel-plainly shows that these merits

discussions occurred. Respondents have no answer; instead, they simply

repeat ad nauseam that Vulcan has "no evidence" of misconduct and urge

deference to a court that reached its decision by treating as gospel a self-

serving declaration from one of Respondents' lawyers, which was never

submitted to the court and which has been abandoned on appeal.

1. Mr. Harrigan's invoices undeniably document ex

parte discussions about the merits of the case.

Respondents do not contest the applicable legal standard or the

related ethical framework. Ex parte discussion of the merits is improper.

Totem Marine Tug & Barge, Inc. v. N Am. Towing, Inc., 607 F.2d 649,

653 (5th Cir. 1979); AAA Rule R-18(a) ("No party ... shall communicate

ex parte with an arbitrator or a candidate for arbitrator concerning the

arbitration."); AAA Code of Ethics, Canon III. Parties may only speak ex

parte with arbitrator candidates about (1) "the general nature of the

controversy"; (2) "the candidate's qualifications, availability, or

-12-

independence in relation to the parties"; and (3) "the suitability of

candidates for selection as a third arbitrator." AAA Rule R-18(a).6

The record evidence is also indisputable. Mr. Harrigan met with

Respondents and their counsel on two different occasions for several

hours; Mr. Harrigan reviewed Respondents' Arbitration Demand at least

three times as it was being drafted and revised; Mr. Harrigan discussed the

draft Demand with Respondents and their counsel; Mr. Harrigan reviewed

the central evidence in the case, the parties' contract; Mr. Harrigan noted

questions "for clarification of facts" and he posed those questions to

Respondents' counsel; and Mr. Harrigan then sent a bill for his work to

Respondents. CP 200, 202, 204-06, 208-10.

In light of the conceded law and undisputed evidence, the only

question posed is whether that evidence conclusively demonstrates that

Mr. Harrigan discussed the merits ofthe arbitration with Respondents or

their counsel - or whether Respondents might create a factual dispute.

What the record evidence shows on its face is that such discussions took

place; surely it at least would allow a rational fact-finder to so conclude.

Respondents' insistence to the contrary is remarkably detached

6 Respondents suggest at one point that that vacatur is discretionary (whereas

confinnation is mandatory). Resp. Br. at 18. But the FAA grounds for vacatur are not

hortatory. In every case where a movant has satisfied one or more lO(a) grounds, the

award is vacated. Respondents do not and cannot cite a single case where a court utilized

its "discretion" and did not vacate the award.

-13-

from the actual record. After quoting Mr. Harrigan's invoices-including

the lines documenting his repeated review of the draft Demand, his

"contract review," and his "conference with [Respondents' counsel] with

questions re background facts"-Respondents baldly assert that "nothing"

in these records supports Vulcan's claim that Mr. Harrigan discussed the

merits. Resp. Br. at 31. If Respondents' detailed allegations, the contract

at issue, and the relevant background facts do not count as the "merits" in

Respondents' view, then it is not clear what constitutes "merits."

Respondents also try to justify their provision of the draft Demands

and the contract to Mr. Harrigan on the grounds that these documents

"contained the names oftwenty individuals and nineteen entities with

some connection to the parties or the dispute," thus allowing Mr. Harrigan

to evaluate whether he had any conflicts. Resp. Br. at 33 n.12. Why Mr.

Harrigan could not simply have been given a list of those individuals and

entities, instead of an advocacy document laying out all of Respondents'

legal claims and factual allegations, goes unexplained.

The only record evidence raises, at a minimum, a strong inference

that Mr. Harrigan did what Respondents concede is improper: discuss the

merits of the dispute with only one side. Respondents are unwilling or

unable to rebut that inference by addressing or explaining what transpired

between them and Mr. Harrigan. Accordingly, the Award is tainted by

-14-

both evident partiality and prejudicial misbehavior and must be vacated.

2. The trial court erred by giving conclusive effect

to an incomplete, self-serving, non-record

declaration from Respondents' counsel.

Notwithstanding the above, the trial court held that there was "no

evidence before the court of inappropriate conduct" during the ex parte

interactions between Mr. Harrigan and Respondents. CP 583:24-25. In

sole support of this pronouncement, which flies in the face of the invoices,

the court quotes Respondents' counsel's self-serving declaration that he

asked no questions of Mr. Harrigan and received no "input" from him. CP

583:25 - 584:3. For multiple reasons, this was reversible error.

First, this after-the-fact declaration of Respondents' counsel was

never submitted to the trial court and is not part of the record. Rather, it

was submitted to Judge Lukens in opposition to Vulcan's motion to

disqualify. The court's reliance on this non-record declaration was not

only improper, but also belies the court's claim to have conducted a truly

independent review of Mr. Harrigan's partiality and misconduct.

Second, even ifthe declaration had been properly submitted to the

court, it cannot eliminate the contrary evidence (i.e., the invoices) and thus

permit a judgment in Respondents' favor. The most that Respondents

could claim is that a factual dispute exists about what transpired during the

ex parte communications, which no one disputes occurred. But, of course,

-15-

ifthere is a material dispute of fact, the fact-finder must resolve it by

holding an evidentiary hearing-and the trial court did not. Instead, the

trial court apparently followed the lead of Judge Lukens, who had

bizarrely decided that counsel's declaration-the factual allegations of one

side-"must be considered as a verity." CP 46.

Third, even if the declaration had been properly submitted to the

court and could somehow be accepted at face value, it could not justify

judgment in Respondents' favor. Even if Mr. Harrigan was asked no

questions and provided no "input," vacatur is still required if Respondents

and their counsel spent hours arguing their side of the case to him. The

declaration carefully avoids denying any such ex parte argument to Mr.

Harrigan and therefore stops short of denying improper contacts.

Perhaps recognizing these many flaws, Respondents in their brief

do not even mention the declaration, which was the only basis for the trial

court's "independent" determination that nothing untoward occurred. This

abandonment only confirms that the court's judgment must be reversed.

3. The trial court erred by rendering judgment

without holding an evidentiary hearing or

allowing discovery.

The trial court, in accepting as true Respondents' contested version

of the facts, held no evidentiary hearing and permitted no discovery. Yet

in light of the strong inference that impermissible merits-based discussions

-16-

occurred, there could be no judgment in Respondents' favor without such

fact-finding. Resolving material factual disputes is what courts do, in

cases seeking vacatur of arbitration awards, as in all others. See, e.g.,

Univ. Commons-Urbana, Ltd. v. Universal Const., Inc., 304 F.3d 1331,

1341-42 (11 th Cir. 2002) (remanding for fact-finding regarding "evident

partiality"); Sanko S.S. Co. v. Cook Indus., 495 F.2d 1260, 1263 (2

nd

Cir.

1973) (remanding "so that an evidentiary hearing may be held and the full

extent and nature of the relationships at issue may be ascertained").

Respondents' only answer is that Vulcan somehow "waived" or

abandoned its right to discovery. Resp. Br. at 46-49. That is both

irrelevant as a matter oflaw and wrong as a matter of fact.

Even if Vulcan had not sought discovery, this would not free the

trial court from its obligation to resolve factual disputes. If the court had

doubts about the accuracy or meaning of the invoices, it should have held

an evidentiary hearing and engaged in independent fact-finding-not

ignored the evidence on one side and assumed the truth on the other.

Nor did Vulcan waive or abandon its discovery request. Its

position in the trial court is the same as its position now: namely, that "no

discovery is necessary [because] the invoices would give any reasonable

person ... an impression [of partiality]." CP 566:5-6. Thus, Vulcan took

the position taken by every litigant who files a motion for summary

-17-

judgment: that judgment in its favor is warranted as a matter of law on the

basis of the undisputed facts; so "discovery" is not "necessary." That

hardly waives a litigant's right to discovery and a hearing if the court

disagrees and believes that there is a material factual dispute. And the

court would be obliged to resolve the dispute.

Vulcan submits that the uncontested invoices are sufficient to

vacate the A ward. If this Court agrees, no discovery is needed and no

further fact-finding is necessary. But if the Court does not find the record

evidence sufficient for vacatur, then, at the very least, further fact-finding

is required in order to test the prima facie evidence of partiality.

D. MR. HARRIGAN'S FAILURE TO DISCLOSE HIS EX

PARTE COMMUNICATIONS CREATES A

REASONABLE IMPRESSION OF PARTIALITY

Vacatur is also required here because Mr. Harrigan failed to

disclose his substantive pre-appointment contacts with Respondents and

their counsel. In non-disclosure cases, the standard for "evident partiality"

under 1O(a}(2} is whether the non-disclosure creates a "reasonable

impression of partiality." Schmitz v. Zilveti, 20 F.3d 1043, 1046 (9th Cir.

1994). "[W]here an arbitrator ... knows of a material relationship with a

party and fails to disclose it, a reasonable person would have to conclude

that the arbitrator was evidently partial." New Regency Productions, Inc.

v. Nippon Herald Films, Inc., 501 F.3d 1101, 1108 (9th Cir. 2007)

-18-

(affirming vacatur for evident partiality). Contrary to Respondents'

suggestion, no evidence of ill motive is required. '''Evident partiality' is

distinct from actual bias." Id. at 1105.

7

Here, Mr. Harrigan's undisclosed ex parte contacts and

relationship with Respondents, and his substantive involvement in the

matter before his appointment, more than creates a reasonable impression

of partiality. This impression is only exacerbated when one considers the

vanilla disclosures that Mr. Harrigan did make. CP 273-77.

E. VULCAN DID NOT WAIVE ITS RIGHTS TO

CHALLENGE MR. HARRIGAN'S MISCONDUCT

In a further attempt to erect a procedural roadblock to judicial

review of their misconduct, Respondents argue that Vulcan waived its

right to challenge the propriety of the pre-appointment discussions with

Mr. Harrigan because Vulcan did not specifically ask about them. Resp.

Br. at 38-41. But the disclosure form did inquire broadly about the

arbitrator's contacts and relationship with Respondents and their counsel,

and knowledge of the "subject matter of this dispute"-all of which

should have elicited good faith disclosure of the ex parte contacts. Mr.

7 Motive is irrelevant in non-disclosure cases and neither of the cases that

Respondents cite (see Resp. Br. at 35) holds otherwise. In both Williams v. NFL, 582

F.3d 863 (8

th

Cir. 2009) and Nationwide Mut. Ins. Co. v. Home Insurance, 278 F.3d 621

(6

th

Cir. 2002), the court first detennined that the plaintiff had waived objection to non-

disclosure before going on to address whether there was actual bias. Neither case

requires a showing of improper motive to vacate an award based on non-disclosure.

-19-

"

Harrigan had a duty to disclose anything suggesting improper contacts, a

duty which could not be evaded through legalistic hrur-splitting.

8

CP 273-

77. Both the applicable law and the AAA Code of Ethics require that

"[a]rbitrators [must] err on the side of disclosure." Commonwealth

Coatings Corp. v. Continental Cas. Co., 393 U.S. 145, 152 (1968); see

also Code of Ethics, Canon II(D).

Absent notice of misconduct, arbitrating parties are reasonably

entitled to assume that arbitrators are acting ethically and in accordance

with applicable rules and law-particularly where there has been specific

agreement on such rules and repeated confirmation of arbitrator

neutrality.9 Vulcan need not specifically ask whether there were

"improper ex parte contacts" or "violations of the AAA Code of Ethics" to

preserve its right to object to them if they occurred. When Vulcan learned

of the improper communications between Mr. Harrigan and Respondents

and their counsel, it objected immediately. CP 379-80. Respondents'

citation of inapposite law only confirms the absence of any waiver.

At the time of Fidelity Federal Bank v. Durga Ma Corp., 386 F.3d

1306 (9

th

Cir. 2004), and in contrast to the present, the applicable AAA

8 Washington State Physicians Ins. Exchange & Ass'n v. Fisons Corp., 122 Wn.2d

299 (1993) addresses and sanctions analogous hair-splitting in the discovery context.

9 See, e.g., CP 238 (email from Respondents' counsel: "each arbitrator should be a

neutral, consistent with AAA Rule 18(a)").

-20-

rules included a presumption that a party-appointed arbitrator was not

neutral, but rather would be partial to the appointing party. After

appointment but before the hearing in that case, the parties and the party-

appointed arbitrators agreed that they would "'act neutrally' when

considering the evidence and rendering an award." Id. at 1309. Despite

knowing that the arbitrator was "initially retained and appointed by Durga

Ma as a non-neutral party-appointed arbitrator," Fidelity did not request

any disclosures. Id. at 1313. Thus, Fidelity merely adopts "a rule that

places the burden on parties to obtain disclosure statements from

arbitrators who were initially party-appointed [and presumptively non-

neutral] but later agree to act neutrally." Id.

Neither the facts nor the "rationale" of Fidelity have any bearing.

Here, the arbitrators were required, presumed, and confirmed to be neutral

- at every step of the way. Unlike Fidelity, the parties here required broad

disclosures that, had they been answered accurately and completely,

would have put Vulcan on notice of the ex parte communications between

Mr. Harrigan and Respondents. Prior to its receipt of the invoices, Vulcan

had no reason or obligation to ask whether Mr. Harrigan had violated the

accepted law and ethical rules, and its not so doing was not a waiver.

F. VACATUR IS ALSO REQllRED BECAUSE THE

ARBITRATORS EXCEEDED THEIR POWERS

Vacatur is required because the Panel exceeded its powers in

-21-

violation of lO(a)(4). Here, the Panel held that Respondents were

lawfully tenninated, yet it (1) awarded damages to Respondents even

though, on the Panel's own theory, Vulcan only breached the contract as

to other persons, and (2) invoked the covenant of good faith and fair

dealing to grant Respondents a right and remedy that they did not and

could not obtain in negotiations. The Award substituted the Panel's

unfounded notion of fairness for what the parties' contract required, in

manifest disregard of the applicable and binding law.

1. The Panel Awarded Respondents a Remedy for a

Breach Only "As To" Other Employees.

Respondents concede that they were at-will employees, whom the

Panel found were lawfully tenninated. Resp. Br. at 43. Thus, there could

be no breach of contract arising from Respondents' tennination.

The Panel held that Vulcan's decision to "simultaneously tenninate

the Private Equity Team and then rehire certain team members, in an

effort to stop the incentive compensation plan," was effectively an attempt

to amend the Plan (and, thus, to breach it) "as to the rehired employees."

CP 34:24 - CP 35:2 (emphasis supplied); see also CP 31 :26 - 32:9, CP

35:3 - 13. The Panel reasoned that by firing and rehiring certain

employees, those employees were deprived of the unvested carry

previously allocated to Respondents (i.e., the Exit Vest), which otherwise

would have reverted to those employees, the remaining team members,

-22-

once Respondents were tenninated. Under no circumstances would the

lawfully-tenninated Respondents have a right to that unvested carry.

Because they were tenninated and not re-hired, Respondents were

contractually excluded from any portion of the unvested carry regardless

of whether Vulcan engaged in a mass tennination and partial rehiring.

The firing and re-hiring of the other employees arguably affected how to

divide up and re-allocate Respondents' share of the unvested carry among

these other employees. CP 31:26 - 32:10; CP 35:4 - 35:13. Yet the Panel

held that its analysis ofthis purported breach as to the rehired employees

"will govern the remedies available to [Respondents]." CP 32:12.

Aside from citing boilerplate cases and generalities about

"deference," all Respondents have to say about this fundamental flaw in

the Award, is the naked assertion (lacking any citation) that the Panel did

find a breach "as to Claimants." Resp. Br. at 42. This is demonstrably

untrue. The Award discovers a breach only "as to the rehired employees."

CP 35:2. Respondents cannot explain why any such breach has relevance

to them, or how it could possibly give rise to, much less govern, remedies

for them. There is no factual nexus or legal support for, on the one hand,

the Panel's finding of breach "as to" rehired employees and, on the other

hand, its Award in favor of Respondents for breach of contract.

-23-

'.'

2. The Panel Grossly Misapplied The Implied

Covenant To Award Respondents a Benefit They

Sought But Failed To Gain During Negotiations.

Delaware law imposes stringent limitations on the use of the

implied covenant of good faith and fair dealing. Neither a court (nor an

arbitration panel) may "substitute its notions of fairness for the terms of

the agreement reached by the parties." Superior Vision Services, Inc. v.

Liastar Life Ins. Co., 2006 Del. Ch. LEXIS 160, at *21 (Del. Ch. August

25,2006). The implied covenant "may not be applied to give [a party]

contractual protections that '[it] failed to secure at the bargaining table. '"

Corp. Property Assocs. 14 Inc. v. CHR Holding Corp., 2008 Del. Ch.

LEXIS 45, at *17-18 (Del. Ch. April 10,2008).

Respondents do not contest the applicable law. Nor do they

dispute Vulcan's analysis of that law in light of the relevant facts. Instead,

the sum and substance of Respondents' counter-argument is that the

matter was previously briefed. Resp. Br. at 44. That is no answer at all.

By its improper use of the implied covenant, the Panel did what

Delaware law forbids. The Award re-writes the VEC Agreement and

invokes the implied covenant to "fashion" a remedy for Respondents that

gives them the very thing they tried and failed to obtain during "protracted

and detailed" negotiations. CP 33:9-11, CP 26:24; see also CP 35:24

(Panel acknowledges that "it is clear" that Vulcan would not agree during

-24-

negotiations to any accelerated Exit Vest).

There is no permissible legal basis for using the implied covenant

to provide Respondents the very benefit they failed to secure at the

bargaining table. Such an Award stands in manifest disregard of Delaware

law and cannot be sustained, deference or not.

v. CONCLUSION

For anyone ofthree grounds under Section lO(a) ofthe FAA, the

Judgment entered against Vulcan should be vacated. Vulcan is further

entitled to its fees, both below and on this appeal.

Submitted this 29

th

day of September 2010.

St hen C. lIley, WSBA #244

Miles A. Yanick, WSBA #26603

Attorneys for Appellants

-25-

"

..

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

The undersigned hereby certifies that on this date I caused a copy

of the attached document - APPELLANTS ' REPLY BRIEF - to be hand

delivered to the attorneys of record listed below:

Richard Yannuth

Matthew Carvalho

Yannuth Wilsdon Calfo PLLC

818 Stewart Street, Suite 1400

Seattle, W A 98101

Attorneys for Respondent David Capobianco

Robert Sulkin

McNaul Ebel Nawrot & Helgren PLLC

600 University Street, Suite 2700

Seattle, WA 98101

Attorneys for Respondent Navin Thukkaram

I hereby certify, under penalty of perjury under the laws of the

State of Washington, that the foregoing is true and correct.

DATED this 29

th

day of September 2010, at Seattle, Washington.

Denise Colvin

You might also like

- United States District Court Central District of CaliforniaDocument24 pagesUnited States District Court Central District of CalifornialegalmattersNo ratings yet

- 92185-7 Petition For ReviewDocument144 pages92185-7 Petition For ReviewPhilip JamesNo ratings yet

- 2013-08 Alphayankee-Vowell 9cir FtcansweringbriefDocument65 pages2013-08 Alphayankee-Vowell 9cir FtcansweringbriefAntsatiana Mu RamarokotoNo ratings yet

- New Jersey Bankruptcy Lawyers - Appellate BriefDocument40 pagesNew Jersey Bankruptcy Lawyers - Appellate Briefreiser100% (4)

- Barbash V STX MTDDocument33 pagesBarbash V STX MTDTHROnlineNo ratings yet

- Levitation Arts V Flyte - Petition For PGRDocument58 pagesLevitation Arts V Flyte - Petition For PGRSarah BursteinNo ratings yet

- District Court of Appeal Case No. A106345 Division Four Superior Court No. C01-03627Document37 pagesDistrict Court of Appeal Case No. A106345 Division Four Superior Court No. C01-03627market-abuseNo ratings yet

- California Opposition To Motion To DismissDocument33 pagesCalifornia Opposition To Motion To Dismissprosper4less8220No ratings yet

- 00866-ATT Corp MotiontodismissDocument33 pages00866-ATT Corp MotiontodismisslegalmattersNo ratings yet

- OLD CARCO, LLC (APPEAL - 2nd CIRCUIT - APPELLANTS' BRIEF - Transport RoomDocument168 pagesOLD CARCO, LLC (APPEAL - 2nd CIRCUIT - APPELLANTS' BRIEF - Transport RoomJack Ryan100% (1)

- NML Capital V Argentina 2013-1-5 Washington Legal Proposed Amicus BriefDocument36 pagesNML Capital V Argentina 2013-1-5 Washington Legal Proposed Amicus BriefAdriana SarraméaNo ratings yet

- B241675 CPR Pacific MarinaDocument65 pagesB241675 CPR Pacific MarinajamesmaredmondNo ratings yet

- United States District Court Central District of CaliforniaDocument21 pagesUnited States District Court Central District of Californiaeriq_gardner6833No ratings yet

- Kohler v. Signature - 12 (C) MotionDocument25 pagesKohler v. Signature - 12 (C) MotionSarah BursteinNo ratings yet

- Shirokov v. Dunlap, Grubb & Weaver - Memorandum of Law in Support of Motion To DismissDocument39 pagesShirokov v. Dunlap, Grubb & Weaver - Memorandum of Law in Support of Motion To DismissDevlin HartlineNo ratings yet

- Ripple Brief Summary JudgmentDocument65 pagesRipple Brief Summary JudgmentSebastian Sinclair100% (1)

- Jane Doe vs. Scientology: RTC's Motion To DismissDocument47 pagesJane Doe vs. Scientology: RTC's Motion To DismissTony Ortega100% (1)

- Gene Pool v. Coastal Harvest - Brief ISO MTDDocument19 pagesGene Pool v. Coastal Harvest - Brief ISO MTDSarah BursteinNo ratings yet

- Valentine v. Collier Stay ApplicationDocument465 pagesValentine v. Collier Stay ApplicationWashington Free BeaconNo ratings yet

- Valentine v. Collier Stay Application PDFDocument465 pagesValentine v. Collier Stay Application PDFWashington Free BeaconNo ratings yet

- 00412-20010307 Pavlovich App ReplyDocument54 pages00412-20010307 Pavlovich App ReplylegalmattersNo ratings yet

- Sedgwick V Delsman 9th Cir Opening BriefDocument34 pagesSedgwick V Delsman 9th Cir Opening BriefEric GoldmanNo ratings yet

- ArtistShare SJDocument41 pagesArtistShare SJEriq GardnerNo ratings yet

- 2:19-cv-01059-RAJ-JRC Document 55 - Defendants Response in Opposition To Coer Motion For Prelim Injunction (With Declarations)Document82 pages2:19-cv-01059-RAJ-JRC Document 55 - Defendants Response in Opposition To Coer Motion For Prelim Injunction (With Declarations)GrowlerJoeNo ratings yet

- Appellants' Opening BriefDocument51 pagesAppellants' Opening BriefgovernorwattsNo ratings yet

- Motion For Attorneys FeesDocument35 pagesMotion For Attorneys FeesSteve Smith100% (1)

- 19-12-16 Qualcomm Reply BriefDocument80 pages19-12-16 Qualcomm Reply BriefFlorian Mueller100% (1)

- THIRD Brief Cranpark V RGI - 6th Circuit - 1-23-15Document55 pagesTHIRD Brief Cranpark V RGI - 6th Circuit - 1-23-15Kenneth SandersNo ratings yet

- 83 Memorandum of LawDocument33 pages83 Memorandum of Lawlarry-612445No ratings yet

- UMG's Motion To DismissDocument30 pagesUMG's Motion To DismissdanielrestoredNo ratings yet

- Stormy Daniels v. Trump, Cohen Motion For ReconsiderationDocument25 pagesStormy Daniels v. Trump, Cohen Motion For Reconsiderationmary engNo ratings yet

- 19910402b in Re Hamilton Taft Adversary Memo in SupportDocument20 pages19910402b in Re Hamilton Taft Adversary Memo in SupportSamples Ames PLLCNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court of The United States: Petitioners, VDocument32 pagesSupreme Court of The United States: Petitioners, VlegalmattersNo ratings yet

- 2020-10-16 Memorandum in Support of CVS Motion To DismissDocument28 pages2020-10-16 Memorandum in Support of CVS Motion To DismissNewsChannel 9 StaffNo ratings yet

- Appellee Answer Brief Oct 12 2018Document55 pagesAppellee Answer Brief Oct 12 2018rick siegelNo ratings yet

- Sec V CoinbaseDocument38 pagesSec V CoinbaseMatthew JenkinsNo ratings yet

- U.S. v. Esquenazi (11th Cir. Appeal) (DOJ Brief)Document120 pagesU.S. v. Esquenazi (11th Cir. Appeal) (DOJ Brief)Mike KoehlerNo ratings yet

- Motion of Appeal by Appaloosa, Centerbridge and Owl CreekDocument53 pagesMotion of Appeal by Appaloosa, Centerbridge and Owl CreekDealBookNo ratings yet

- Ken Dandar v. Scientology: State Appeal 2014Document63 pagesKen Dandar v. Scientology: State Appeal 2014Tony OrtegaNo ratings yet

- Kohler Motion To DismissDocument38 pagesKohler Motion To DismissgmaddausNo ratings yet

- SEC Reply Hodges Apr 30Document35 pagesSEC Reply Hodges Apr 30glimmertwins100% (1)

- Memorandum of Law in Support of Defendants' Motion To Dismiss For Lack of Personal Jurisdiction and Forum Non ConveniensDocument32 pagesMemorandum of Law in Support of Defendants' Motion To Dismiss For Lack of Personal Jurisdiction and Forum Non ConveniensNat WilliamsNo ratings yet

- NAFC v. Scientology: Response Narconon International's Motion To DismissDocument28 pagesNAFC v. Scientology: Response Narconon International's Motion To DismissTony OrtegaNo ratings yet

- Dvorak Mar 23Document103 pagesDvorak Mar 23glimmertwins100% (1)

- 42 Ventures, LLC v. Rend Et Al 1 20-Cv-00228-DKW-WRP 25 Memorandum Re MotionDocument36 pages42 Ventures, LLC v. Rend Et Al 1 20-Cv-00228-DKW-WRP 25 Memorandum Re MotionDavid MichaelsNo ratings yet

- Campo Flores Response To Presentence Reports August 2017Document60 pagesCampo Flores Response To Presentence Reports August 2017InSight CrimeNo ratings yet

- Gov Uscourts Nysd 501755 80 0Document16 pagesGov Uscourts Nysd 501755 80 0Simon AlvarezNo ratings yet

- Wright V Beck Opening BriefDocument59 pagesWright V Beck Opening Briefwolf woodNo ratings yet

- Noye V Pennell & Associates, Inc Et AlDocument25 pagesNoye V Pennell & Associates, Inc Et AlSamuel RichardsonNo ratings yet

- 00491-Costar BriefDocument67 pages00491-Costar BrieflegalmattersNo ratings yet

- In The: PetitionerDocument46 pagesIn The: PetitionerantitrusthallNo ratings yet

- Greene V Paramount MSJDocument33 pagesGreene V Paramount MSJTHROnlineNo ratings yet

- Shrem Filing Nov. 5Document29 pagesShrem Filing Nov. 5CCNNo ratings yet

- 2010-04 Homeassureii 11cir FtcbriefDocument38 pages2010-04 Homeassureii 11cir FtcbriefAntsatiana Mu RamarokotoNo ratings yet

- 2014-01-15 US (Szymoniak) V American Doc 241-1 Memo MTD JPMCDocument23 pages2014-01-15 US (Szymoniak) V American Doc 241-1 Memo MTD JPMClarry-612445No ratings yet

- Petition for Certiorari Denied Without Opinion: Patent Case 98-1972.From EverandPetition for Certiorari Denied Without Opinion: Patent Case 98-1972.No ratings yet

- Petition for Certiorari – Patent Case 01-438 - Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 52(a)From EverandPetition for Certiorari – Patent Case 01-438 - Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 52(a)No ratings yet

- Mike Rawley PDFDocument6 pagesMike Rawley PDFFinally Home RescueNo ratings yet

- Inmate Found Dead at Snohomish County Jail in Everett MYEVERETTNEWSDocument1 pageInmate Found Dead at Snohomish County Jail in Everett MYEVERETTNEWSFinally Home RescueNo ratings yet

- NORMAN L REAM (President) - OpenCorporates PDFDocument2 pagesNORMAN L REAM (President) - OpenCorporates PDFFinally Home RescueNo ratings yet

- Report To Congressional Requesters: United States Government Accountability OfficeDocument76 pagesReport To Congressional Requesters: United States Government Accountability OfficeFinally Home RescueNo ratings yet

- NORMAN L REAM (Agent) - OpenCorporates PDFDocument2 pagesNORMAN L REAM (Agent) - OpenCorporates PDFFinally Home RescueNo ratings yet

- NORMAN L REAM (President) - OpenCorporates PDFDocument2 pagesNORMAN L REAM (President) - OpenCorporates PDFFinally Home RescueNo ratings yet

- Fleury v. Bowden, Washington Court of Appeals, State Courts, COURT CASE PDFDocument4 pagesFleury v. Bowden, Washington Court of Appeals, State Courts, COURT CASE PDFFinally Home RescueNo ratings yet

- James normandyBeenVerified PDFDocument10 pagesJames normandyBeenVerified PDFFinally Home RescueNo ratings yet

- Michael E. Rawley (President) - OpenCorporates PDFDocument2 pagesMichael E. Rawley (President) - OpenCorporates PDFFinally Home RescueNo ratings yet

- JACQUELINE M RASHLEGER (Manager) - OpenCorporates PDFDocument2 pagesJACQUELINE M RASHLEGER (Manager) - OpenCorporates PDFFinally Home RescueNo ratings yet

- MICHAEL E RAWLEY (Manager) - OpenCorporates PDFDocument2 pagesMICHAEL E RAWLEY (Manager) - OpenCorporates PDFFinally Home RescueNo ratings yet

- Certificate of Involuntary Dissolution/RevocationDocument1 pageCertificate of Involuntary Dissolution/RevocationFinally Home RescueNo ratings yet

- MICHAEL E RAWLEY (Treasurer) - OpenCorporates PDFDocument2 pagesMICHAEL E RAWLEY (Treasurer) - OpenCorporates PDFFinally Home RescueNo ratings yet

- Lawrence Ream Lawyer Profile PDFDocument2 pagesLawrence Ream Lawyer Profile PDFFinally Home RescueNo ratings yet

- Personal Information: Location: Vacaville, CADocument5 pagesPersonal Information: Location: Vacaville, CAFinally Home RescueNo ratings yet

- Certificate of ReinstatementDocument1 pageCertificate of ReinstatementFinally Home RescueNo ratings yet

- FeatherlyBeenVerified PDFDocument6 pagesFeatherlyBeenVerified PDFFinally Home RescueNo ratings yet

- BegayBeenVerified PDFDocument9 pagesBegayBeenVerified PDFFinally Home RescueNo ratings yet

- Billi Morsette PDFDocument11 pagesBilli Morsette PDFFinally Home RescueNo ratings yet

- ChristiansenBeenVerified PDFDocument7 pagesChristiansenBeenVerified PDFFinally Home RescueNo ratings yet

- BeenVerified PDFDocument6 pagesBeenVerified PDFFinally Home RescueNo ratings yet

- Alvin J Windy Boy PDFDocument9 pagesAlvin J Windy Boy PDFFinally Home RescueNo ratings yet

- Aircraft Accidents and Incidents - 2Nm E. of Blyn, Washington 98382 Wednesday, A PDFDocument7 pagesAircraft Accidents and Incidents - 2Nm E. of Blyn, Washington 98382 Wednesday, A PDFFinally Home RescueNo ratings yet

- Certificate of Involuntary Dissolution/RevocationDocument1 pageCertificate of Involuntary Dissolution/RevocationFinally Home RescueNo ratings yet

- BeenVerified PDFDocument7 pagesBeenVerified PDFFinally Home RescueNo ratings yet

- 2014 Cerificate of Involuntary Disolution Revocation PDFDocument1 page2014 Cerificate of Involuntary Disolution Revocation PDFFinally Home Rescue0% (1)

- Certificate of ReinstatementDocument1 pageCertificate of ReinstatementFinally Home RescueNo ratings yet

- 13thInfoContact PDFDocument1 page13thInfoContact PDFFinally Home RescueNo ratings yet

- Carolyn Y. Heyman-Layne, Member: Sedor Evans &, LLCDocument1 pageCarolyn Y. Heyman-Layne, Member: Sedor Evans &, LLCFinally Home RescueNo ratings yet

- Alaska: Articles of IncorporationDocument2 pagesAlaska: Articles of IncorporationFinally Home RescueNo ratings yet

- The Competition (Amendment) Act, 2023Document21 pagesThe Competition (Amendment) Act, 2023Rahul JindalNo ratings yet

- Legal English Vocabulary (English-German)Document6 pagesLegal English Vocabulary (English-German)MMNo ratings yet

- NGP To Ahemdabad Train Ticket PDFDocument2 pagesNGP To Ahemdabad Train Ticket PDFSaurabh UkeyNo ratings yet

- Trust and Reliability: Chap 6Document24 pagesTrust and Reliability: Chap 6Zain AliNo ratings yet

- LCC Group PitchingDocument4 pagesLCC Group Pitchingfizul18320No ratings yet

- USU Law Journal, Vol.5.No.1 (Januari 2017)Document11 pagesUSU Law Journal, Vol.5.No.1 (Januari 2017)Abdullah NurNo ratings yet

- Fa1 Batch 86 Test 19 March 24Document6 pagesFa1 Batch 86 Test 19 March 24Paradox ForgeNo ratings yet

- San Lorenzo Development Corporation vs. Court of AppealsDocument13 pagesSan Lorenzo Development Corporation vs. Court of AppealsElaine Belle OgayonNo ratings yet

- Open 20 The Populist ImaginationDocument67 pagesOpen 20 The Populist ImaginationanthrofilmsNo ratings yet

- I. Definitions 1. "Agreement" Means This Settlement Agreement and Full and Final ReleaseDocument27 pagesI. Definitions 1. "Agreement" Means This Settlement Agreement and Full and Final Releasenancy_sarnoffNo ratings yet

- Ee-1151-Circuit TheoryDocument20 pagesEe-1151-Circuit Theoryapi-19951707No ratings yet

- Velasco V People GR No. 166479Document2 pagesVelasco V People GR No. 166479Duko Alcala EnjambreNo ratings yet

- People V Lopez 232247Document7 pagesPeople V Lopez 232247Edwino Nudo Barbosa Jr.No ratings yet

- EY Philippines Tax Bulletin July 2016Document26 pagesEY Philippines Tax Bulletin July 2016evealyn.gloria.wat20No ratings yet

- Was The WWII A Race War?Document5 pagesWas The WWII A Race War?MiNo ratings yet

- Position Paper Yabo GilbertDocument2 pagesPosition Paper Yabo GilbertGilbert YaboNo ratings yet

- Cyquest 3223 (Hoja Tecnica) PDFDocument2 pagesCyquest 3223 (Hoja Tecnica) PDFThannee BenitezNo ratings yet

- Reevaluation FormDocument2 pagesReevaluation FormkanchankonwarNo ratings yet

- Culasi, AntiqueDocument10 pagesCulasi, AntiquegeobscribdNo ratings yet

- Sample Assignment Name: Matrix No: CompanyDocument20 pagesSample Assignment Name: Matrix No: CompanynurainNo ratings yet

- Relevancy of Facts: The Indian Evidence ACT, 1872Document3 pagesRelevancy of Facts: The Indian Evidence ACT, 1872Arun HiroNo ratings yet

- Intervention) in WP (C) PIL No. 5/2020: CM No. 3022/2020 (Filed by Mr. Sachin Sharma, Advocate SeekingDocument23 pagesIntervention) in WP (C) PIL No. 5/2020: CM No. 3022/2020 (Filed by Mr. Sachin Sharma, Advocate SeekingJAGDISH GIANCHANDANINo ratings yet

- 13 Stat 351-550Document201 pages13 Stat 351-550ncwazzyNo ratings yet

- 2020 - UMass Lowell - NCAA ReportDocument79 pages2020 - UMass Lowell - NCAA ReportMatt BrownNo ratings yet

- Norman Dreyfuss 2016Document17 pagesNorman Dreyfuss 2016Parents' Coalition of Montgomery County, MarylandNo ratings yet

- ID Act, 1947Document22 pagesID Act, 1947Abubakar MokarimNo ratings yet

- List of 1995Document6 pagesList of 1995trinz_katNo ratings yet

- A Case Study in The Historical and Political Background of Barangay 77 Banez VillDocument7 pagesA Case Study in The Historical and Political Background of Barangay 77 Banez VillPogi MedinoNo ratings yet

- The Astonishing Rise of Angela Merkel - The New YorkerDocument87 pagesThe Astonishing Rise of Angela Merkel - The New YorkerveroNo ratings yet

- Letter - For - Students - 1ST - Year - Programmes (Gu)Document2 pagesLetter - For - Students - 1ST - Year - Programmes (Gu)Ayush SinghNo ratings yet