Professional Documents

Culture Documents

English Construction Latin Influence

Uploaded by

arisarisaris2Original Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

English Construction Latin Influence

Uploaded by

arisarisaris2Copyright:

Available Formats

The Absolute Construction in Old and Middle English: A Case of Latin Influence?

This paper addresses the absolute construction in OE (Old English) (and to some extent Middle English), with special focus on its origin. This non-finite construction consists of a participle and a nominal subject, usually both in the dative, and functions as an adverbial clause. An example is ofslegenum Pendan hyra cyninge in t Mercna mg, ofslegenum Pendan hyra cyninge, Cristes geleafan onfengon (The Mercians received Christs faith, when their king Pendan was slain). Earlier research on this topic provides two opposite views: either the construction is considered Latin in origin and is treated as a syntactic loan (Kisbye, 1971; Visser, 1973), recently sometimes as a lexical loan (Timofeeva, 2009), or it is regarded as a native, Germanic construction (Bauer, 2000). Preference has generally been with the former. My position is situated in between: taking my cue from Matsunami (1966), who states that Generally the use of the [] participle was declining in all the G[er]m[ani]c dialects but that the classical languages reinforced its functions, I argue that absolutes constitute a native OE construction that was on the brink of disappearing, as is shown by its low frequency in native text material (cf. Timofeeva, 2009), but was kept alive by the practice of Latin translation (cf. Johansons 2002 selective frequential copying). Recent investigation indeed favours the idea of absolutes as an Indo-European construction (Costello, 1982; Bauer, 2000). As such it is likely for Germanic, and in a later stage OE to have inherited this structure from the proto-language. Evidence is provided by the fact that most Germanic languages at some point used this construction and shared the dative as preferred case (Gothic: Costello, 1980). Further arguments against viewing OE absolutes as loans come from a quantitative and qualitative corpus investigation of OE texts (cf. appendix): (i) Latin ablative absolutes, when indeed translated in OE as absolutes, are consistently put in the dative case, from the earliest OE records onwards, both in glosses and real translations. If these translations were to be regarded as loans, a more diversified case choice (genitive, accusative) reflecting the translators hesitation could be expected, at least in the early records, as the ablative itself is not available in OE. (ii) The absolute construction, as a translational equivalent of the Latin absolute, is seen to be in decline towards the early Middle Ages (30% 10%) and is reluctantly used during the whole OE period (15%-20%), except in glosses (95%). If borrowing were at stake, one would anticipate the reverse: cautious use in the beginning and gradual increase when the construction becomes more familiar. The divergence in translational options (e.g. by finite adverbial clauses) also shows there was no especially urgent need for this construction in the OE language that would justify a loan in the first place. (iii) It is sometimes argued that absolutes were borrowed to be able to stay as true as possible to the divine Latin word order and syntactic structure when translating religious material. But if this was sufficient reason to incite borrowing, again one would suppose frequencies to be much higher than what my analysis reveals (from 0% to 35% across the various texts). More generally, this study is part of a more extensive investigation which via the discussion of the origin of absolutes in general, their use both in translated and native OE texts, as well as general translational theory in Anglo-Saxon culture, wishes to shed a new light on the presence of dative absolutes in Old and Middle English.

References Bauer, Brigitte. 2000. Archaic Syntax in Indo-European. The Spread of Transitivity in Latin and French. Berlin New York: Mouton de Gruyter; Costello, John R. 1980. The absolute construction in Gothic. Word 31.1. 91-104; Costello, John R. 1982. The Absolute Construction in Indo-European: a Syntagmemic Reconstruction. Journal of Indo-European Studies 10.3-4. 235-252; Johanson, Lars. 2002. Contact-induced change in a code-copying framework. In Mari C. Jones & Edith Esch (eds.) 2002. Language change. The interplay of internal, external and extra-linguistic factors. Contributions to the sociology of language 86. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. 285-313; Kisbye, Torben. 1971. An historical outline of English syntax. Aarhus, Denmark: Akademisk Boghandel; Matsunami, Tamotsu. 1966. Functional Development of the Present Participle in English: Native Syntactic Functions of the OE Present Participle (I). In Department of Literature in Kyushu University (eds.) 1966. Studies in Commemoration of the Fortieth anniversary of the Department of Literature in Kyushu University. Fukuoka: Department of Literature in Kyushu University. 315-348; Timofeeva, Olga. 2009. Translating the Texts where et verborum ordo mysterium est: Late Old English Idiom vs. ablatives absolutus. The Journal of Medieval Latin 19; Visser, Frederikus Theodorus. 1973. An Historical Syntax of the English Language. Leiden: Brill. Corpus The York-Toronto-Helsinki Parsed Corpus of Old English Prose (YCOE). 2003. Compiled by Ann Taylor, Anthony Warner, Susan Pintzuk, and Frank Beths. University of York: (http://www-users.york.ac.uk/~lang22/YCOE/YcoeHome.htm). Texts analysed include: Bedes Ecclesiastical History, Gregorys Pastoral Care, Gregorys Dialogues, the Blickling Homilies, The Gospel according Saint Matthew from the West-Saxon Gospels, the Regularis Concordia glosses, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle E, lfrics Lives of Saints, lfric's Homilies Supplemental and Mary of Egypt.

You might also like

- Brian Beyer Legends of Early Rome Authentic Latin Prose For The Beginning Student PDFDocument126 pagesBrian Beyer Legends of Early Rome Authentic Latin Prose For The Beginning Student PDFgregoriodegante100% (1)

- Spelling 101Document37 pagesSpelling 101anirNo ratings yet

- The Translation of Abstract Nouns in ChineseDocument23 pagesThe Translation of Abstract Nouns in ChineseDavid MoserNo ratings yet

- Translation StudiesDocument7 pagesTranslation Studiessanamachas100% (1)

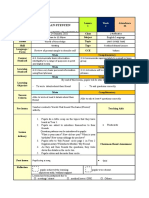

- Lesson Plan - Factoring A Perfect Square Trinomial and A Difference of SquaresDocument4 pagesLesson Plan - Factoring A Perfect Square Trinomial and A Difference of Squaresapi-286502847100% (4)

- Lesson Plan For Observation A Detailed Lesson Plan in Grade 9Document3 pagesLesson Plan For Observation A Detailed Lesson Plan in Grade 9Gerald E Baculna40% (5)

- Translation StudiesDocument15 pagesTranslation StudiesMimmo SalernoNo ratings yet

- THINK L4 Unit 12 Grammar BasicDocument2 pagesTHINK L4 Unit 12 Grammar BasicЕгор КоренёкNo ratings yet

- Chiaradonna Universals Commentators-LibreDocument77 pagesChiaradonna Universals Commentators-LibreGiancarloBellina100% (2)

- Sample Term Paper PDFDocument18 pagesSample Term Paper PDFChristian Frilles91% (22)

- Language ChangeDocument33 pagesLanguage ChangePradeepa Serasinghe100% (1)

- Exegetical Dictionary of The New TestamentDocument4 pagesExegetical Dictionary of The New Testamentmung_khat0% (2)

- Translation StudiesDocument11 pagesTranslation Studiessteraiz0% (1)

- A Modern History of Written Discourse Analysis - 2002Document33 pagesA Modern History of Written Discourse Analysis - 2002Shane Hsu100% (1)

- Roberta - Facchinetti Corpus - Linguistics (25.years - On)Document392 pagesRoberta - Facchinetti Corpus - Linguistics (25.years - On)Yuliya Kalymon DanchevskaNo ratings yet

- English Literature and Language Review: Retranslation Theories: A Critical PerspectiveDocument11 pagesEnglish Literature and Language Review: Retranslation Theories: A Critical PerspectiveDannyhotzu HtzNo ratings yet

- Free Time Unit 5Document26 pagesFree Time Unit 5Jammunaa RajendranNo ratings yet

- Personal & Professional Development Plan PDFDocument16 pagesPersonal & Professional Development Plan PDFElina Nang88% (8)

- Рибовалова Periods of the translation theory developmentDocument25 pagesРибовалова Periods of the translation theory developmentValya ChzhaoNo ratings yet

- Porter, Stanley E. & O'Donell, Matthew BrookDocument39 pagesPorter, Stanley E. & O'Donell, Matthew BrookalfalfalfNo ratings yet

- Translation and Time: Migration, Culture, and IdentityFrom EverandTranslation and Time: Migration, Culture, and IdentityNo ratings yet

- Teoria Si Practica Traducerii - Curs de LectiiDocument27 pagesTeoria Si Practica Traducerii - Curs de LectiiAnonymous tLZL6QNo ratings yet

- Future Perfect Lesson PlanDocument5 pagesFuture Perfect Lesson PlanHassan Ait AddiNo ratings yet

- Lexical Borrowing Concepts and Issues 20 PDFDocument20 pagesLexical Borrowing Concepts and Issues 20 PDFOninNo ratings yet

- Linguistic Approach To Translation TheoryDocument22 pagesLinguistic Approach To Translation Theorym_linguist100% (2)

- Chapter 10: Historical LinguisticsDocument36 pagesChapter 10: Historical LinguisticsNoor KareemNo ratings yet

- Monograph in Eng. 508Document9 pagesMonograph in Eng. 508Paolo NapalNo ratings yet

- ALEXIADOU Perfects Resultatives and Auxiliaries in Early EnglishDocument75 pagesALEXIADOU Perfects Resultatives and Auxiliaries in Early EnglishjmfontanaNo ratings yet

- Translating and Re-Narrating Multilingual Texts: The Extreme Case of Finnegans WakeDocument18 pagesTranslating and Re-Narrating Multilingual Texts: The Extreme Case of Finnegans WakeSimona AnselmiNo ratings yet

- A General and Unified Theory of The Transmission Process in Language Contact - Review - PhariesDocument5 pagesA General and Unified Theory of The Transmission Process in Language Contact - Review - PhariesgomezrendonNo ratings yet

- Weireich, Labov, Herzog1968 PDFDocument78 pagesWeireich, Labov, Herzog1968 PDFMichelle BaxterNo ratings yet

- Ancient Indo-European Dialects: Proceedings of the Conference on Indo-European Linguistics Held at the University of California, Los Angeles April 25–27, 1963From EverandAncient Indo-European Dialects: Proceedings of the Conference on Indo-European Linguistics Held at the University of California, Los Angeles April 25–27, 1963No ratings yet

- Translation and Style A Brief Introduction (Jean Boase-Beier)Document4 pagesTranslation and Style A Brief Introduction (Jean Boase-Beier)zardhshNo ratings yet

- Metaphors and Translation PrismsDocument12 pagesMetaphors and Translation PrismslalsNo ratings yet

- Implications of Research Into Translator Invisibility : Basil HatimDocument22 pagesImplications of Research Into Translator Invisibility : Basil HatimSalimah ZhangNo ratings yet

- ПерекладознавствоDocument128 pagesПерекладознавствоNataliia DerzhyloNo ratings yet

- Uniformitarian Principle: Dr. D. Anderson Michaelmas Term 2007Document7 pagesUniformitarian Principle: Dr. D. Anderson Michaelmas Term 2007o8o6o4No ratings yet

- Weireich, Labov, Herzog1968Document79 pagesWeireich, Labov, Herzog1968Lucero CadenaNo ratings yet

- Course: Engl-411Document15 pagesCourse: Engl-411غدير .No ratings yet

- Bouchard Denis. 1995. The Semantics of SDocument4 pagesBouchard Denis. 1995. The Semantics of SLayton HariettNo ratings yet

- Translators Endless ToilDocument6 pagesTranslators Endless ToilMafe NomásNo ratings yet

- Louis Hay, Le Texte Nexiste PasDocument14 pagesLouis Hay, Le Texte Nexiste PasAzalea Romero RubioNo ratings yet

- 049 - Rosemarie Glaser (Leipzig) - Terminological Problems in Linguistics, With Special ReferenceDocument7 pages049 - Rosemarie Glaser (Leipzig) - Terminological Problems in Linguistics, With Special ReferenceAliney SantosNo ratings yet

- California Linguistic Notes Volume XXXV No. 1 Winter, 2010Document7 pagesCalifornia Linguistic Notes Volume XXXV No. 1 Winter, 2010kamy-gNo ratings yet

- Contrastive Linguistics and Linguistic TypologyDocument18 pagesContrastive Linguistics and Linguistic TypologyBecky BeckumNo ratings yet

- Lexical BorrowingDocument21 pagesLexical BorrowingAlbastroiu DianaNo ratings yet

- The Rise of Expletives in EnglishDocument1 pageThe Rise of Expletives in EnglishSergio RojoNo ratings yet

- Chapter69 PDFDocument20 pagesChapter69 PDFMei XingNo ratings yet

- Recursion and The Infinitude ClaimDocument25 pagesRecursion and The Infinitude ClaimGuaguanconNo ratings yet

- Why UniversalsDocument11 pagesWhy UniversalsMichael ResanovicNo ratings yet

- Reading Week 1Document3 pagesReading Week 1Ana Paulina López ÁlvarezNo ratings yet

- Agreement BibDocument99 pagesAgreement BibmiguelmrmNo ratings yet

- Norms, New Words, and Empirical RealityDocument15 pagesNorms, New Words, and Empirical Realitythis.getuseNo ratings yet

- The Linguistic Study of Early Modern English-How Bad Can Bad Data BeDocument28 pagesThe Linguistic Study of Early Modern English-How Bad Can Bad Data BeJames AlvaNo ratings yet

- The English Grammar - A Historical PerspectiveDocument24 pagesThe English Grammar - A Historical PerspectiveKriKeeNo ratings yet

- A Comparison of Jerome and Horace Model On TranslationDocument4 pagesA Comparison of Jerome and Horace Model On Translationsevvalgundes8No ratings yet

- Review of Jim Miller & Regina Weinert, Spontaneous Spoken Language: Syntax and Discourse. Oxford: Clarendon, 1998. Pp. Xiv+457Document6 pagesReview of Jim Miller & Regina Weinert, Spontaneous Spoken Language: Syntax and Discourse. Oxford: Clarendon, 1998. Pp. Xiv+457Elías NadamásNo ratings yet

- The Development of Case in GermanicDocument27 pagesThe Development of Case in GermanicNevena SladakovićNo ratings yet

- (S. H. Levinsohn) The Relevance of Greek Discourse Studies To Exegesis (Artículo)Document11 pages(S. H. Levinsohn) The Relevance of Greek Discourse Studies To Exegesis (Artículo)Leandro VelardoNo ratings yet

- Traducere in Japonia MeijiDocument30 pagesTraducere in Japonia MeijiAlina Diana BratosinNo ratings yet

- Introduction: Multimodality As Challenge and Resource For TranslationDocument13 pagesIntroduction: Multimodality As Challenge and Resource For TranslationДіана ЧопNo ratings yet

- Definition and History of TranslationDocument3 pagesDefinition and History of TranslationAfrian Reastu PrayogiNo ratings yet

- Unit 1 Ban CuoiDocument28 pagesUnit 1 Ban CuoiThanh Mai NgôNo ratings yet

- Philip Durkin, The Oxford Guide To Etymology. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009. Pp. X +350. Hardback 25.00Document7 pagesPhilip Durkin, The Oxford Guide To Etymology. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009. Pp. X +350. Hardback 25.00LuminitaNo ratings yet

- The Greek Verbal Network Viewed From A Probabilistic Standpoint (Stanley E. Porter)Document39 pagesThe Greek Verbal Network Viewed From A Probabilistic Standpoint (Stanley E. Porter)Jaguar777xNo ratings yet

- Bilingualism in Ancient Society: Language Contact and The Written Text - Bryn Mawr Classical ReviewDocument2 pagesBilingualism in Ancient Society: Language Contact and The Written Text - Bryn Mawr Classical Reviewвалькирия 1No ratings yet

- 1 Woolfolk 2020 Development 60-62Document3 pages1 Woolfolk 2020 Development 60-62Mikylla CarzonNo ratings yet

- Assignment For FTC 101. THEORIESDocument7 pagesAssignment For FTC 101. THEORIESYvonne BulosNo ratings yet

- Ingles Act 4 Quiz 1 Unit 1Document11 pagesIngles Act 4 Quiz 1 Unit 1Nelly Johanna Fernández ParraNo ratings yet

- Philisophy and Logic - AristotleDocument21 pagesPhilisophy and Logic - AristotleRalphNo ratings yet

- Image Segmentation: FemurDocument18 pagesImage Segmentation: FemurBoobalan RNo ratings yet

- Test Bank For Essentials of Human Behavior Integrating Person Environment and The Life Course Second EditionDocument11 pagesTest Bank For Essentials of Human Behavior Integrating Person Environment and The Life Course Second Editionbevisphuonglc1u5No ratings yet

- Chapter 2 MultigradeDocument3 pagesChapter 2 MultigradeLovely Mahinay CapulNo ratings yet

- ANAPHY 101 Unit II Module 1Document3 pagesANAPHY 101 Unit II Module 1Vj AleserNo ratings yet

- Health Promotion Reflection - AdvocacyDocument2 pagesHealth Promotion Reflection - Advocacyapi-242256654No ratings yet

- Team Action PlanDocument6 pagesTeam Action Planapi-354146585No ratings yet

- Fce Test 33 PDFDocument43 pagesFce Test 33 PDFJulia MorenoNo ratings yet

- Introduction To OBDocument14 pagesIntroduction To OBIshaan Sharma100% (1)

- Set A: Murcia National High SchoolDocument3 pagesSet A: Murcia National High SchoolRazel S. MarañonNo ratings yet

- Simulation and Modelling (R18 Syllabus) (19.06.2019)Document2 pagesSimulation and Modelling (R18 Syllabus) (19.06.2019)dvrNo ratings yet

- EDUU 512 RTI Case Assignment DescriptionDocument2 pagesEDUU 512 RTI Case Assignment DescriptionS. Kimberly LaskoNo ratings yet

- Importance of Accurate Modeling Input and Assumptions in 3D Finite Element Analysis of Tall BuildingsDocument6 pagesImportance of Accurate Modeling Input and Assumptions in 3D Finite Element Analysis of Tall BuildingsMohamedNo ratings yet

- Behavior Specific Praise Statements HandoutDocument3 pagesBehavior Specific Praise Statements HandoutDaniel BernalNo ratings yet

- Moore 2011 2Document16 pagesMoore 2011 2João AfonsoNo ratings yet

- LKPD Berbasis PJBLDocument12 pagesLKPD Berbasis PJBLAsriani NasirNo ratings yet

- Managing ConflictDocument16 pagesManaging ConflictGwenNo ratings yet

- Job Description For HR HR Recruiter Responsibilities IncludeDocument4 pagesJob Description For HR HR Recruiter Responsibilities Includevivek sharmaNo ratings yet

- Communication Skills & Technical Report WritingDocument77 pagesCommunication Skills & Technical Report WritingSabir KhattakNo ratings yet