Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Tamper Proof Tech Fails

Uploaded by

Ryan HawkinsOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Tamper Proof Tech Fails

Uploaded by

Ryan HawkinsCopyright:

Available Formats

Tamper-Proof Prescription Drugs May Halt Abuse

29 June 2008 NewScientist.com news service Jim Giles

It's a class of drug abused by 1.5 million Americans. To quit, addicts have to go cold turkey: vomiting, diarrhoea, insomnia. Thousands die every year from overdoses. Add up the days lost from work and the money spent caring for addicts, and the toll reaches $10 billion annually. You'd be forgiven for thinking that the drugs in question are crack cocaine or heroin. Instead, the culprits are prescription painkillers such as oxycodone and hydrocodone. By binding to and disrupting the activity of brain cells that control the experience of pain, they ease the suffering caused by a range of conditions from back problems to terminal cancer. When milder painkillers fail, opioids bring vital relief. Around a decade ago, when medical organisations began encouraging doctors to do more to help patients in pain, opioids, which can be formulated to offer long-lasting relief, seemed to be the answer. But although pain management has improved, the huge rise in prescriptions is fuelling an epidemic of opioid abuse (see Graph), which is costing lives. In 2005, prescription opioids played a role in 8500 fatal overdoses, more than the figures for cocaine and heroin combined. "Judged by any measure - person years of life lost, healthcare costs, self reports of drug abuse - the prescription drug problem is a crisis that is steadily worsening," said Leonard Paulozzi, an epidemiologist at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta, Georgia, at a recent Senate hearing on unintentional drug overdoses. Studies have also shown that people are turning to the internet in droves to find ways to tamper with prescription drugs (New Scientist, 3 June 2006, p 6). Now drug companies are fighting back with a solution of their own - tamper-resistant opioids. Even if some people find ways around these new pills, experts say that anything that makes abuse harder will help cut the numbers of addicts. None of the new pills has yet been approved for sale. But earlier this month, Pain Therapeutics of San Mateo, California, and King Pharmaceuticals of Bristol, Tennessee, asked the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to approve Remoxy, a new form of OxyContin, one of the most widely prescribed opioid-based painkillers.

Part of OxyContin's value as a painkiller is its ability to release the opioid oxycodone over a 12-hour period. But if someone crushes the pill and then snorts or injects the powder they can get the entire dose at once - along with an intense high. To remove this possibility Remoxy's makers mixed oxycodone with gelatin to form a rubbery pill that simply bends when hit with a hammer. They mixed the opioid oxycodone with gelatin to form a rubbery pill that simply bends when hit with a hammer In some cases, instead of crushing pills, addicts may try to dissolve them and drink or inject the solution. But James Green of King Pharmaceuticals says the company's tests show that if people put the pill in water and then drink it, they don't get all the oxycodone at once. He declined to explain why, saying the results were commercial secrets. Meanwhile, Grnenthal of Aachen, Germany, is taking a similar approach by developing opioid pills that are supertough. In tests at the New York State Psychiatric Institute, 40 OxyContin addicts were given a placebo version of Grnenthal's pill and asked what they would like to use to crush it. "They asked for razors, knives, hammers, paperweights, pliers," says Sandra Comer, who helped run the tests. Each received their instrument of choice. Some were able to break the pill into a few smaller pieces, but none could crush it. "Someone asked for a blender," adds Comer. "The pill just spun around." Those safeguards should deter at least some abusers - one of the tragedies of the current problem is the number of young people abusing opioids. Arthur Lipman, a pain expert at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City, says that teenagers often steal opioids from their parents for use at parties. Surveys of American teens show that around 10 per cent have abused an opioid in the past year. But if teenagers cannot easily get a high, they are likely to find the drugs less attractive. "That could be life-saving," says Lipman. More-experienced addicts pose a greater challenge. Comer's work suggests that a hard pill prevents casual abuse, but it won't be so easy to defeat determined addicts. They may find a way of dissolving Grnenthal's pill, while methods for tampering with the rubbery Remoxy pills are already being discussed on internet chatrooms devoted to opioid abuse. So Alpharma of Bridgewater, New Jersey, has created Embeda, a morphine pill that might prove harder to abuse. Like OxyContin, its active ingredient morphine tends to come as a slow-release pill that is commonly crushed by addicts. But Embeda has a core made of a substance called naltrexone, which binds to opioid receptors in the brain, preventing the morphine from reaching the same receptors. The core is coated to prevent the naltrexone from being absorbed into the body if the pill is simply swallowed. If crushed, the naltrexone is released and mixes with the morphine, so if the powder is then snorted, the morphine won't have any effect. Alpharma plans to apply for FDA approval next month. No one is under any illusion that the tamper-resistant pills will deter everyone. "I don't know if addicts have better imagination than our people," says Jack Howard of Alpharma. "But they are pretty smart." Some even think the drugs could make things worse. Labelling them as abuse-resistant could make doctors less likely to monitor patients for signs of abuse or even make patients think the drugs are safer. Partly because of these fears, members of an FDA advisory panel in May voted against approving another tamper-resistant opioid developed by Purdue Pharma of Stamford, Connecticut, which makes OxyContin. "You want to ensure that the problem you're trying to solve doesn't become worse," says Frank Vocci of the National Institute on Drug Abuse in Bethesda, Maryland, who voted against approval. However, Purdue could gain approval if the labelling on the new opioid was cautious enough to prevent doctors assuming the product was safe, he says. Experts say the other tamper-resistant opioids have a good chance of getting approval if they are labelled appropriately.

September 20, 2009 Slipstream Taking the Fun Out of Popping Pain Pills By NATASHA SINGER HOW can you get a faster high from sustained-release pain pills like OxyContin? Let me count some of the ways. People have crushed them using bookends, hammers, mortars and pestles, and then snorted the powder, according to doctors who study addiction. Theyve chewed and swallowed fistfuls of pills. Theyve minced the pills in blenders, pulverized them in coffee grinders, dissolved them in water and then injected the liquid. Even for those of us who dont inhale, the misuse and abuse of prescription painkillers called opioids should matter because, putting moral and ethics aside for the moment, its costing us billions of dollars. In a 2008 federal survey, an estimated 4.7 million Americans were found to have used prescription pain relievers for nonmedical reasons in the previous month. The abuse of opioids now costs at least $11 billion annually in excess medical care including overdoses by adults and accidental ingestion by children, said Howard G. Birnbaum, a health economist with the Analysis Group in Boston. Corporate America loves a void, and now some pharmaceutical companies are developing innovative opioids intended to deter tampering and meet the markets need. Some pills under development are rubberlike and harder to crush. Others contain ingredients that cause unpleasant reactions in the body, like flushing or itching, if the pill is adulterated. Taking a cue from exploding ink packets that can render stolen money unusable, some pills have an outer opioid layer and an inner core that, if tampered with, releases a drug that counters the high of the pain reliever. Embeda, made by King Pharmaceuticals in Bristol, Tenn., uses the last of these strategies. Scheduled to arrive in drug stores this weekend, Embeda is the first of the new so-called abusedeterrent opioids to reach the market. But, the Food and Drug Administration has approved Embeda only as a pain reliever, not as an abuse-deterrent drug, an agency spokeswoman said. In a clinical study of Embeda, a majority of volunteers experienced less euphoria when they took a crushed form of the drug compared to immediate-release morphine. But the company has not yet established the real-world significance of the results. The hope for abuser-unfriendly pills is that they might eventually decrease abuse. The drawback is that the pills represent (bad pun alert!) a fix for only one part of a very complex problem. In a sense, the new opioids reflect the ups and downs of broader efforts to overhaul health care: addressing cosmetic aspects of the problem without thoroughly grappling with systemic causes. While legislators are diligently trying to figure out how to get medical coverage for millions of uninsured people, the insurance gap is just one symptom of an ailing, inefficient medical system inclined toward reactive rather than preventive care. Likewise, the new pain relievers are intended to deter an important cause of opioid abuse: tampering. But, for people who simply ingest too many whole, intact pills, tamper-resistant opioids still dont reduce overdose risks, said Dr. Nathaniel P. Katz, the chief executive of Analgesic Research, a research and consulting firm in Boston that specializes in the development of pain treatments. (Dr. Katz and every other expert quoted here say they have worked as paid consultants for King Pharmaceuticals or conducted research sponsored by the company). Drug companies have promoted novel opioids as nonaddictive on other occasions and failed, said Dr. Katz, who is also a neurologist and adjunct faculty member at Tufts University medical school. He cited heroin, introduced by Bayer as a branded drug in 1898, and OxyContin, introduced by Purdue Pharma in 1995. Moreover, according to Steven D. Passik, a clinical psychologist at Memorial SloanKettering Cancer Center in Manhattan, the advent of so-called abuse-deterrent opioids also doesnt solve another, larger problem: uneven state and physician monitoring of the legal circulation of opioids. It does not obviate the need to put together a strategy to teach every prescriber to do Addiction Medicine 101, Dr. Passik said. A more complete strategy to combat opioid abuse, he said, would involve asking busy primary care doctors to routinely assess how vulnerable to addiction a patient might be and to closely track patients taking opioids for chronic pain. That, of course, means some health insurers would have to step up and cover more frequent urine tests and doctor visits for those patients. Meanwhile, on a regulatory level, some states should devote greater resources to online prescription

monitoring systems, Dr. Katz said. These are databases used by pharmacists and doctors to check whether a patient already has multiple opioid prescriptions, a phenomenon called doctor shopping that is a red flag for drug abuse. On a federal level, the F.D.A. is developing a comprehensive risk management system for sustainedrelease opioids, an agency spokeswoman said. The program may include a certification requirement for doctors who prescribe and pharmacies that dispense those kinds of painkillers. But the F.D.A. could solve another slice of the problem people who share legally prescribed opioids with friends and family members if it required a patient training program, Dr. Katz said. If doctors verbally warned patients, Dont share, its a felony, and you will kill your neighbors, friends and family, youd have a lot less sharing, he said. Finally, opioid abuse might be diminished if there were national standards on how to dispose of unused pills, said Sandra Comer, a professor of clinical neurobiology in the psychiatry department at Columbia University medical school. Often, Dr. Comer said, patients are prescribed an opioid for a month or more, but their pain subsides after a week or two. Then they have leftover pills in their medicine cabinets which are open to pilfering by, for example, college-age children or visitors. But nobody knows what to do with unused pills because pharmacies wont take them back. Flushing them down the toilet is a bad idea because the chemicals can pollute the water system. Some experts recommend mixing the pills with used kitty litter or coffee grounds and throwing them in the garbage. Perhaps, in addition to patient training, the F.D.A. might institute a give-back program akin to government buy-back deals for guns for anybody housing an inventory of unused prescription painkillers.

Last edited by bronyraur; 09-22-2009 at 08:03 AM.. Reason: added paragraphs

You might also like

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Codine LinctusDocument20 pagesCodine LinctusArdi BükïtUdäl JuniorNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Dopesick - Opioid Epidemic On Healthcare and SocietyDocument11 pagesDopesick - Opioid Epidemic On Healthcare and Societyapi-482726932No ratings yet

- New Zealand Data Sheet: OrxigaDocument49 pagesNew Zealand Data Sheet: OrxigaLabontu IustinaNo ratings yet

- FurosemideDocument4 pagesFurosemideapi-3797941100% (1)

- Recording Forms (Masterlist) School Forms - Kinder To Grade 7Document16 pagesRecording Forms (Masterlist) School Forms - Kinder To Grade 7lourdes estopaciaNo ratings yet

- Pharma - SkinDocument8 pagesPharma - Skinreference books100% (1)

- Book1 1Document2 pagesBook1 1Trisha Mae CaymoNo ratings yet

- Hepatitis B VaccineDocument4 pagesHepatitis B VaccineShantal AbelloNo ratings yet

- Substance: Marquis Mecke Mandelin Folin Froehde LiebermannDocument1 pageSubstance: Marquis Mecke Mandelin Folin Froehde LiebermannJhayNo ratings yet

- Therapeutic and Toxic ConcentrationsDocument8 pagesTherapeutic and Toxic ConcentrationsReyadh JassemNo ratings yet

- Drug Discovery and Development Lecture NotesDocument75 pagesDrug Discovery and Development Lecture NotesJameel BakhshNo ratings yet

- 1 Traditional Drugs and Herbal Medicines PhytotherapyDocument28 pages1 Traditional Drugs and Herbal Medicines PhytotherapyDian Ayu Novitasari Emon100% (1)

- (PCOL) Cardio and Renal Drugs - Test BankDocument20 pages(PCOL) Cardio and Renal Drugs - Test BankGriselle GomezNo ratings yet

- Dopamine, Naloxone, MorphineDocument2 pagesDopamine, Naloxone, MorphineArvin Bernardo QuejadaNo ratings yet

- To Be Filled Up by The School Nurse/ Class Adviser To Be Filled Up by The Vaccination TeamDocument13 pagesTo Be Filled Up by The School Nurse/ Class Adviser To Be Filled Up by The Vaccination TeamShinSan 77No ratings yet

- DAIRY HEALTH 2020 Iuh RoutesDocument24 pagesDAIRY HEALTH 2020 Iuh Routesmark angelNo ratings yet

- PH 1.13:BETA Blockers: Dr. Lavakumar S Professor Dept of Pharmacology SssmcriDocument31 pagesPH 1.13:BETA Blockers: Dr. Lavakumar S Professor Dept of Pharmacology SssmcriBeena ShajimonNo ratings yet

- PPR - LISTS - Registered Medicine Price List - 20211230Document333 pagesPPR - LISTS - Registered Medicine Price List - 20211230Abdulla KamalNo ratings yet

- ISONIAZIDDocument2 pagesISONIAZIDXerxes DejitoNo ratings yet

- Attapulgite Vs CiproDocument6 pagesAttapulgite Vs CiproAyu Syifa NaufaliaNo ratings yet

- MD Tanjil 22Document1 pageMD Tanjil 22wasi Wasikhan890yahoo.comNo ratings yet

- Toxicology Principles ExplainedDocument10 pagesToxicology Principles ExplainedsandeepNo ratings yet

- Stock Per 30 Nov 20 HargaDocument13 pagesStock Per 30 Nov 20 HargaLutfi QamariNo ratings yet

- Revisi K-E Data Kesesuaian FormulariumDocument158 pagesRevisi K-E Data Kesesuaian FormulariumSilvia Cahya WibawaNo ratings yet

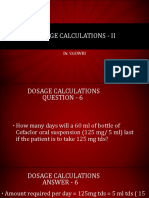

- Dosage Calculation Questions & AnswersDocument11 pagesDosage Calculation Questions & AnswersBlue FlashesNo ratings yet

- Stock Opname 2021 23-01-2022Document42 pagesStock Opname 2021 23-01-2022yunitacahyaniiNo ratings yet

- A Drug Study On: PhenylephrineDocument6 pagesA Drug Study On: PhenylephrineAlexandrea MayNo ratings yet

- Dopamine PrecursorDocument5 pagesDopamine Precursormarie gold sorilaNo ratings yet

- PRESCRIPTION REGULATION SUMMARYDocument2 pagesPRESCRIPTION REGULATION SUMMARYroxiemannNo ratings yet

- Nasal Spray Condensed - HOW TO MAKE NASAL SPRAY FOR DRVGSDocument3 pagesNasal Spray Condensed - HOW TO MAKE NASAL SPRAY FOR DRVGSInés Grande BarrasNo ratings yet