Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Marcus T. Anthony - Crisis, Deep Meaning and The Need For Change

Uploaded by

AuLaitRSOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Marcus T. Anthony - Crisis, Deep Meaning and The Need For Change

Uploaded by

AuLaitRSCopyright:

Available Formats

Crisis, Deep Meaning and the Need for Change Marcus T.

Anthony

I have failed in my foremost task to open peoples eyes to the fact that man has a soul, there is a buried treasure in the field, and that our religion and philosophy are in a lamentable state.

Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung, towards the end of his life (quoted in Ross, 1993, p. 126).

One day, when I was about eight years old, my school principal Mr Suley got up on the morning assembly and spoke from the heart. Now, more than 30 years later, I cannot remember all the details. What I do remember though, was his tone of deep concern. He spoke about war, the environment, cooperation, and simply what it means to be a decent human being. And I will never forget what he said at the end of it all. You are the future of this world. My generation has already had a go and we messed it up. You must do better, or we will not be here much longer. Of all the things anybody ever said in my schooling days, this was probably the most impactful. Here he was, an older man approaching retirement, and he decided to speak about something more than keeping the playground clean, punishing misbehaviour, or the principals old favourite: Get ready because the exams are coming up. Mr Suley spoke of life itself, and what it means to be a human being on this planet. They were words of deep meaning, words that moved me. They were moving because they were not just spoken, but felt. I went through another ten years in the public education system after that, and I honestly cannot recall any teacher or administrator speaking with such impact, or about something so meaningful. This silence always puzzled me. Mr Suley has probably passed on by now. I heard some years ago that he was involved in a car accident, and that his wife had been killed. I was deeply saddened. It would also have been a tragedy if he had passed up the option of speaking

meaningfully on the assembly all those years ago. He may not be here anymore, and maybe he suffered greatly though personal tragedy. But the seed he planted on that day lives on in the man writing this article in 2008. Many of us can probably remember a defining moment from our school days when a teacher spoke from the heart and moved us, made us think deeply. But what about teachers today? How many of us have ever engaged in a discussion or a lesson where we shared something from deep within us? The answer for many educators today is that we rarely touch upon the deeply meaningful. Why is that? At first glance the answer might seem obvious. There is the issue of personal vulnerability. Maybe the students will ridicule or ignore us. Maybe we will offend someones religious or philosophical beliefs. And who wants to upset parents in these times of legal accountability? Besides, it is not in the curriculum or syllabus, so why go there? Yet, rather appropriately, the absence of meaning goes deeper. To understand why education discourses have become an effective litany of surfaces we have to look at the situation in depth. And that takes us into the awkward territory of human spirituality. Yes, the dreaded s word. This understanding includes examining the way that our society has developed, who controls the dominant discourses, and the ways of knowing which undergird them. And finally it incorporates the very way in which we view the human mind and its intelligence. In the analysis which follows I am going to outline the historical and paradigmatic factors which have created this restriction of cognitive wholeness and the resultant lack of depth in modern public education. In this time of shifting global power and economic uncertainty, the restoration of cognitive depth along with associated right-brained cognitive processes, is something we can no longer ignore. It is a necessity not only for economic and social stability, but for the long-

term survival of the human race. In this paper I am going to argue that the current economic woes are the perfect time to begin to initiate change in curriculum, and expand the ways of knowing that we employ in the classroom. The extrication of meaning The effective extrication of deep meaning from modern discourses on science and education can be traced back to the scientific revolution of the seventeenth century. It was at this time that what I call the critical/rational worldview became entrenched. (Anthony 2006). At the dawn of modern science, ideas related to meaning were removed from the dominant discourses. The focus of science and philosophy became the measurable and empirical. Philosophy became mistrusted, and the spiritual and mystical became increasingly associated with superstition and the ignorance of the dark ages (Tarnas 2000). By 1850 the experimental age in science had dawned, and by the late nineteenth century in psychology introspection became seen as an unreliable way to understand the human mind (Huff 2003; Pickstone 2000). Reductionism became dominant in mainstream science, an especially biology. Human beings came to be seen as biological automata. The search for the soul had ended. As Francis Crick (1994), the man who first assembled a replica of the DNA molecule put it, we are nothing but a bunch of neurons. Western public education followed in kind, and with the establishment of the modern secular state, removed from curricula ideas related the meaning and purpose. The industrial revolution brought the mass of humanity into the cities, and people became instruments of industry, effectively commoditised for deployment in the consumer society (Anthony 2005, 2008). This state of affairs has resulted in the present situation where education is heavily focused upon the 3Rs and vocational training (Moffet 1994). Another factor is the increasing influence of computer technology, which improves IT literacy and increases the amount of data available to students, but permits little room for introspection or reflection upon the meaning of the data brought forward (Oppenheimer 2004). Finally, the problem is compounded by an excessive focus upon assessment

testing. Yet, as James Moffett (1994) pointed out in his lifelong mission to restore meaning to classrooms, a third and vital component of education has been excluded - personal and spiritual development, including the capacity to employ inner and reflective ways of knowing. So now educators find themselves teaching in education systems which have a tendency to avoid references to deeply meaningful ideas, and human spirituality. Inner worlds and the intuitive have been devalued, or completely leached from the curriculum. Even Waldorf schools, set up by mystic Rudolph Steiner, have greatly restricted references to the spiritual (Oppenheimer, 2004). As discipline problems in schools increase partly, I believe, because learning has become increasingly divorced from meaning many teachers have turned to amusement and entertainment to engage the student. Using songs, Youtube clips, movies and games can greatly enhance student participation and interest. I often use them myself. Yet no amount of amusement is going to replace the deeper human need for contemplation and meaning in our lives. My experience as a teacher has led me to believe that many students are actually thirsting for knowledge in this domain of human enquiry. To use an analogy, the deadening realisation after waking up from a night of heavy drinking is that the world remains cold sober real. The grim realisation after a successful and entertaining lesson is that even though it was fun and the syllabus objectives were met, we are left with little sense of what it all means. These are deep questions that I am suggesting need addressing in a healthy education system. What does it mean to be human? What does it mean to be part of this world and even this universe? Why do we live and die, and what should we do in the sometimes painful bit in between? Are we just here for the cash, or to go shopping on the weekend? And most of all, how do I establish a healthy relationship with my own psyche? I believe teachers have a duty to teach more than merely the syllabus and to make it interesting. Whether we like it or not, whenever we step into a classroom we

teach values, attitudes - and implicitly, meaning. For even the silence on meaningful discussion and the refusal to look within is an implicit meaning in itself. It implies that inner worlds and the spiritual are out of bounds, and therefore illegitimate domains of educational and social discourse. Admittedly, in order to begin to address the deeper questions I refer to, we need either explicit or implicit institutional and societal approval to do so. And this is where it must be appreciated that schools play a normative function in society, and have been created, at least in part, as instruments of social control. Franklin (1999), after an examination of the journal The Review of Educational Research, found that the idea of social control has been central in the development of educational curricula. At around the time of World War One in the United States, educational administrators attempted to create a scientific method of curriculum development, in the name of social efficiency. Those curriculum designers attempted to use the curriculum as a medium to manage society. Franklin argues that public schools and their curricula have been used to establish control amidst the social problems of industrialisation, urbanisation, and immigration. In Franklins understanding, this agenda was transposed via the scientific language of psychology and learning (Franklin 1999). To top it off, the industrialisation of society has brought with it a corporate domination associated with the powerful controlling influence of mainstream establishment culture (Franklin 1999; Hart 2000; Loye 2004; Milojevi? 2005), as Table 1 (below) indicates. Former Princeton academic David Loye (2004 p 26) equates this Establishment with the paradigm of the Pseudo-Darwinian Mind. The control of society and science has been assisted by a largely passive and compliant academia, and the influence of television, publishing industries, and the mass media by an economic and power elite. A Darwinian survival of the fittest ethos and selfishness are the ruling motifs which legitimise and fund dominant science (Loye 2004 p 26). The key point is that all this social evolution, and the resultant control structures, has placed minimal value upon the spiritual growth of the individual, nor upon

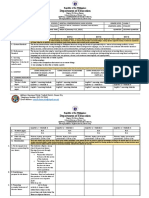

personal empowerment, the latter of which is a threat to the power of institutions and the state (Moffett 1994). It may be assumed that as a result, individual access to spiritual knowledge and the development of wisdom has suffered. This is because such cognitive experiences require inner and often non-ordinary states of consciousness (Braud 2003; Grof 2000), and these have been almost totally absent from the educational processes of state control and the critical/rational ways of knowing which have dominated Western society for several centuries. (Table 1, below) The teacher is a subject within these power structures. This context has to be acknowledged by any teacher wishing to initiate a deeper and more meaningful discourse within the classroom Other ways of Knowing The mediation of ways of knowing within both a societal and educational context has much bearing on this problem. In order to begin to explore the issue of meaning at a deep level, and to facilitate the cognitive processes involved, we need to expand upon our ways of knowing. I have argued elsewhere that the development of Western society since the time of the ancient Greeks has featured a power interplay between three primary worldviews (Anthony 2006). I call these the critical/rational (scientific), the religious/spiritual (religious) and the mystical/spiritual (mystical) worldviews respectively. There is some degree of overlap amongst them, but they are fairly distinct. The key point is that over time, and in different locations and cultures, each of these worldviews has held more power and sway than at other times. Presently Western society and education have become dominated by the critical/rational worldview. Each worldview has preference for specific ways of knowing, with a valorisation of particular cognitive processes and certain approaches to knowledge acquisition. Table 1, below summarises these worldviews and their differing ways of knowing.

Table 1: Three worldviews and their ways of knowing Critical rationality Ways knowing of Externalised. Religious spirituality Mystical spirituality

External/internal. Internal/transpersonal. Subjective, internal. Experiment, analysis, Faith. Affective. Intuition & classification, integrated intelligence. Rational/ mathematical/logical, Rational may be seen as linguistic. Some rational/linguistic lower. analysis & intelligences. Affective & intuitive classification. Text-based rejected. spirituality. Fragmented, conscious mind in control, ego may dominate. Ordinary states of consciousness. Extended mind; transcendence of ego as ideal; non-linear, immediate. Nonordinary states of consciousness. Collapse of subject & object.

States of Fragmented, consciousness conscious mind & ego in control. Ordinary states of consciousness. Subject/ object relations Divinity/ numinous

Subject/object split. Subject/object split.

Seen as illusion, self- Transcendent. deception, pathology. Text/faith-based divinity. Numinous distrusted.

Imminent. Divinity may be embraced; or numinous & deities may be downplayed. surrenders to

Power

Individualism. State, Divine, mediated Ego

structures

corporate, scientific via church, divine/transpersonal. & educational religious The guru or master. institutions. institutions, clergy or human authority. Modernity (incl. education). Scientific materialism. Atomistic ancient Greeks. Skeptics. Nominalism. Christianity (Augustine, scholasticism, Protestantism, fundamentalism). Christian mysticism, gnosticism, paganism, Romanticism, New Age/counter-culture.

Examples

To appreciate the dominance of critical/rational ways of knowing in the modern West, we need to appreciate the dynamic historical interplay between these three worldviews. Mystical/Spiritual and religious ways of knowing have always featured strongly in western societies. Mystical/spiritual ways of knowing have tended to be non-dominant, existing beyond religious and scientific/secular power structures. Yet they have played a crucial role in many societies. Their role in Ancient Greece has often been understated by modern historians of science. During the thirteenth century mysticism flourished in Europe, until it was violently put down by the Church. In the seventeenth century in North America witchcraft, a form of paganism was brutally persecuted. In the mid-eighteenth to mid-nineteenth century the Romantic Movement existed as a strong social, cultural and creative force across the West. Much of the essence of the Romantic movement rose again in the counter-culture movement of the 1960s, and continues as a secondary discourse to this day, in such spaces as non-Western culture, alternative medicine and the new age movement.

Religious movements and institutions have dominated throughout large periods of history, most notably from the early first millennia right through to around the seventeenth century. It remains a strong force in many cultures and communities. After the scientific revolution, critical/rational ways of knowing became much more dominant. Classification as a way of knowing emerged around 1500 (Pickstone 200), as the scholastic movement took hold in Europe, and played a strong role in the emergence of modern science (Huff 2003). Around 1800 analysis came to the fore, and experimentation as a way of knowing began to dominate around 1850 (Pickstone 2000). As science replaced religious authority as the prime arbiter of the real, the benefits became obvious. Progress in human technology accelerated at a rate never seen before. China and the Islamic world, which had once been powerful and advanced civilizations, allowed political and/or religious power to hold sway over freedom of information and the independence of individual and institutional autonomy. They fell far behind in terms of their technological sophistication. Europe, and then the USA, came to dominate the world. The rejection of the affective A crucial part of this historical process has been the rejection of affective ways of knowing (feelings), and with them familiarity with the subtle feelings of the intuitive mind. While these play a crucial role in mystical spiritual and religious/spiritual worldviews, feelings were deliberately expunged from the process of scientific enquiry. The problem is that the realm of feeling is crucial to understanding the deeper resonance of life, and much of what it means to be human. A great chasm has now opened up between the intuitive experience of being human, and the shallowness of rationality-dominated science and education, which denies the essence of life and humanity. In short, the critical/rational worldview denies the spiritual fabric of life itself, and this is an artificial imposition which has alienated much of the common public. The scientific community and educators have something in common:

they are increasingly concerned that their fields are losing touch with the common person. The common denominator is the critical/rational worldview and its extrication of deeper and affective ways of knowing: the loss of meaning. Presently in academia right across the developed world, there is a pronounced emphasis upon the empirical and quantitative. This means that philosophical and spiritual ways of knowing are greatly downplayed.i[i] Researchers who have qualitative approaches are finding it more difficult to gain employment. When universities search for new staff, they typically seek individuals who can gain funding for research. And funding tends to go to researchers and proposals which are empirical and quantitative in nature. This is a continuation of the general domination of the critical/rational worldview since the seventeenth century. But looking at it in a more short-term perspective, it is also a reflection of the materialism engendered by booming economies. At such times money and industry tend to gain more power and control. Technoscienceii[ii] dominates over pure science and philosophical enquiry. Now, with the recent economic turmoil, I predict this trend will shift. Societies, universities, educators and governments will begin to ask deeper questions, and with them philosophical approaches to learning will begin to resurface. They might even start talking about spirituality. The definition of intelligence, and its context as social control The conceptualisation of human intelligence is another factor which plays a strong role in the dominance of critical/spiritual ways of knowing in modern education and society. For when we try to make meaning of the world, we are implicitly employing human intelligence, and the way we employ human intelligence is culturally mediated (Richardson 2000). The way we think of intelligence cannot be fully appreciated without understanding the social and historical context of the concept of intelligence itself. Francis Galtons work in the mid-to-late nineteenth century was important in the development of intelligence and aptitude tests. He applied statistics to the study of intelligence. (Gardner, Kornhaber, & Wake, 1996). Galton gathered data about peoples weight, height, hand strength, power of breath, head size, and

psychophysical characteristics such as reaction times and ability to distinguish fine sensory discriminations (Gardner et al. 1996 p 46). These tests focused on sensory perception, which reflected the philosophy of the British empiricists such as Locke and Hume, who believed that all data entered the mind through the senses (Gardner et al. 1996). The assumption was that those with a greater capacity for sensory perception had a greater amount of data to work with, and greater ability to make discriminations (Gardner et al. 1996 p 47). This foreshadowed the mind-as-computer metaphor which currently dominates cognitive psychology (Maddox 1999). Although Galtons tests were later shown to be of limited predictive value (Gardner et al. 1996 p 47), his use of statistical methods helped establish the normative approach to understanding mind and behavior which dominates modern psychology to this day. This includes the development of factor analysis, which is widely used in determining IQ test results (Gardner et al. 1996 p. 51). Recent mainstream IQ theorists such as Arthur Jensen (1998) and Hernstein and Murry (1994) follow comparable normative approaches. The key here is that cognitive abilities that are not easily measured tend to be left off the map. These have inevitably diminished the subtle, the intuitive and the spiritual, all important inner ways of knowing that are required for contemplating meaning and appreciating he subtle nuances which underpin wisdom and self-awareness. At approximately the same time as Galton, an alternative approach to testing intelligence and psychophysical processes was being developed by Alfred Binet in France (Gardner et al. 1996 p 47). Binet was assigned the task of developing a way to identify those students who were at risk of failing the system. This was at the height of the rapid urbanisation occurring in the industrial revolution, when masses of people were pouring in from the countryside to the cities. Binet was more interested in comprehension, judgment, and the capacity for reason and inventiveness. His tests became widely adopted, and focused upon simple everyday things, such as comparing two objects from memory, counting from twenty to zero, and comprehending abstract words and disarranged

sentences (Gardner et al. 1996 p 49). Binets tasks therefore focused upon verbal and linguistic, arithmetic, mnemonic and artistic abilities. We may note that both Binets and Galtons approaches made no attempt to examine any deeper reflective processes that might require introspection or even mildly non-ordinary states of consciousness. Binets focus in particular helped entrench the dominance of externalised and phenomenological approaches to human intelligence, by avoiding inner worlds and self-reflective ways of knowing. The tendency of some of those who later employed Binets methods was to interpret intelligence as a single universal measure. Gradually, the idea of the IQ score as something discrete and measurable became reinforced - a distinct, quantifiable thing within an individuals head (Gardner et al. 1996 p 50). Stepping back for a moment and looking at the big picture, it can be appreciated that these developments in the definition of human intelligence occurred in the context of the late nineteenth century and the first half of the twentieth century. The measurability fixation of experimentalism and mechanistic science was dominating (Ross 1993). Eventually in the classroom, teachers brought with them the implicit belief that intelligence was about the ability to master rational/linguistic and mathematical/logical processes. The inner and reflective processes of mind became forgotten they became invisible domains which played little or no part in the classroom or curriculum. For the way that we think of students as being smart inevitably affects both assessment procedures, and the way that we teach. How I sought meaningful education Yet even the acknowledgement and awareness of this context is not enough if educators are to begin to expand cognitive depth in education. In order for a teacher to begin to open spaces for deeper meaning in classrooms, and to open inner worlds, she must have explored those realms herself. She must have at least attempted to come to terms with the deeper issues in her own life. These are not things that can be communicated through a syllabus document, or simply written

into the curriculum. They have to be deeply explored, deeply felt and deeply meant by the educator. In my own case, I have made it a point in my life to do just that. This has been a process which has occurred over about twenty years, but to relate a relevant anecdote, I will merely backtrack to the year 2000. At that time I was teaching English in a smallish city in south-eastern Taiwan. One morning I woke up alone in my apartment, and knew something was very wrong. I looked around. The room seemed strangely desolate and empty. I had everything I needed at that time: a nice place to live, an attractive Taiwanese girlfriend, and debt-free financial stability, if not quite security. The room was the same as it had been the day before and the week before. What had changed was something within me. I felt empty. In fact it was more than that. It was a sense of depression, a feeling which I was not accustomed to. Fortunately, I had spent some years working deeply with the inner worlds of my psyche, including practicing mediation and doing emotional work on myself. So I knew that there was a message for me in the feeling. The following morning I awoke and the feeling was there again. But this time there was a song playing in my head. It was a song by the Beatles: Nowhere man.

Doesn't have a Knows not where Isn't he a bit like you and me?

point he's

of going

view, to,

To paraphrase Lennon and McCartney, I had become a real nowhere man, sitting in my nowhere land, making nowhere plans for nobody. In the random universe of the Western critical/rational worldview, synchronicities like this are dismissed as mere coincidences, haphazard events which you can make of what you will. But I saw it as something deeply meaningful. I reflected upon things for a week or so, and decided to take some action. Life had become easy, but meaningless. I realised I had become stuck within my own comfort zone Five years before that week in 2000 I had deferred my enrolment in a doctoral programme in my home country, Australia. Now, after some reflection, I decided

to resume. But what would I study? I could have gone with the demands of the economy, and enrolled in the most prestigious school that would take me, and study whatever the education market was demanding. Instead I made a decision to go for what really moved me. I decided I wanted to study the frontiers of human intelligence, including the interface of rational and intuitive ways of knowing. In short, I chose to focus upon a spiritual domain of education. Shortly afterwards, through another serendipitous event, I happened to find out about a university educator and futurist named Sohail Inayatullah, who lived in Australia, but worked one week a month at Tamkang University in Taipei. As it turned out, Sohail also worked through the University of the Sunshine Coast in Australia. I arranged a meeting with Sohail, and was instantly drawn to the kinds of ideas he espoused. I soon applied to enter the Policy Studies doctoral programme in Australia, under Sohails supervision. Although I encountered resistance from some administrators who did not care much for my esoteric interests, I was permitted to enroll. As I embarked upon my doctoral studies, which I did part-time, I discovered something wonderful. Because I was studying knowledge which I had deep passion for, the entire process became almost effortless. As I read and wrote my dissertation I found I had more words and thoughts than I could ever possibly use. I began to publish some of these in journals, mainly in the area of Futures Studies. That began a period of prolific output. I completed a 110 000 word dissertation, wrote a book based on it (which gained publication), wrote more than a dozen peerreviewed articles, three book chapters, delivered three conference papers and wrote several critical academic reviews all in less than six years - and all while working fulltime in education. What is more, I deliberately activated my intuition and employed other ways of knowing during the research process. Before any research session or reading, I sat quietly and went through the questions I wished to answer. I then trusted what I call the feeling sense to help guide me to the correct books, papers, chapters,

paragraphs and sentences which I needed to answer my questions. If I started reading something which just didnt feel right, I ditched it, and read something that did move me. I kept a journal in which I wrote down intuitive insights as they came to me. In the initial stages I wrote and wrote and wrote, allowing the subconscious mind to formulate and synthesise information, sometimes independently of any conscious understanding of how it was all happening.iii[iii] I discovered at a personal level that life becomes much less effortful when you listen to the heart, when you tap into intuitive intelligence. It takes a lot of the guesswork out of things. It connects the individual with something greater than the individual self. The entire experience is quintessentially spiritual. This process which I used to initiate and conduct my academic research is literally unheard of in academic circles. Notice I did not write non-existent. It is well known that many academics and scientists work with their intuitive feelings, and the history of science is dotted with anecdotes of synchronicities which assisted the evolution of human knowledge (Grof 2000). It is just that they do not talk about it much in public. The problem and the way forward All this can be traced back to devaluation of the intuitive mind in recent western history. The empirical and quantitative are wonderful assets to human knowledge. The emphasis upon these in recent centuries has led to tremendous advances in knowledge. This has accelerated since the beginning the twentieth century with the dominance of technoscience, which has facilitated the integration of science with consumer/technological society. Yet this has come at a price. Human beings are losing touch with inner worlds and the subtle awareness of the essential spiritual dimensions of life. This is not only the case in Western cultures. In China, the political environment has led to the systematic extinguishing of spiritual discourse in education, at all levels. Worldwide students are crying out for something, anything, which will help them address the deep questions within. Teachers and administrators often seem

unable, or unwilling, to address this issue. Devoid of meaning, schooling can become a drudgery of cynicism and confusion. At times educators look like a flock of sheep, following themselves around in ever-diminishing circles. Have we become a land of the nowhere men and women? I believe a genuine education has to honour the full range of human cognitive potentials. This includes the utilisation of a more complete range of ways of knowing. The decline of the West? What we can do about it There is yet another factor to consider here. Things are shifting, and fast. There is a real danger that the Western world, including the United States, is in decline. In relative economic terms, this is indisputable. After World War Two, the US economy represented about 50 per cent of the total world economy. Now it is approximately 25 per cent. The Chinese economy has been growing at around ten per cent for some thirty years, and will likely become the biggest world economy sometime in the middle of this century. As Thomas Friedman (2007) pointed out in The World is Flat, the new world is one where Western economies must compete with new, emerging and developing societies. In China, for example, my brother-in-law, who works as a security guard, earns US$100 a month, and has to feed a non-working wife and a young child. His wage is not untypical of lower-skilled workers in the smaller cities of China. How can an American, British or Australian firm compete against that? The answer in short is that it cannot. The way forward for the West is, in part, the way backward. But it is not really backward. It is simply bringing to the fore the lost parts of ourselves, the parts that were eliminated in the industrial revolution. In Futures Studies we call this the disowned future (Inayatullah 2008). As an educator who has worked in Taiwan, mainland China and Hong Kong, and has taught in Australia, New Zealand, and visited American schools, I can report that there are strengths and weaknesses to each civilisations approach to knowledge. The truth is that most

East Asian systems have also ditched deep meaning. But to speak generally, they have not embraced individual freedom of thought, intellectual autonomy, creativity, nor allowed the inner worlds of the psyche to flourish. The advantage they have is that they value education in a way that we have forgotten. Although teachers have also lost some respect in modern East Asian society, the typical school still contains a large number of competitive, hungry students eager to learn, and who fear being excluded from the group, or failing the system. In every Western country I have visited, it has become cool to be a rebel. Since the time of James Dean, kids have loved thumbing their noses at the system. And now we can add being disrespectful, rude and arrogant, as well as having the attitude that the system owes me. This is a dangerous situation for the Western world. Our education systems are sowing the seeds of a rapid civilisational decline. The kinds of attitudes that are dominating are those that will breed mediocrity and failure. The world does not bow to the Western God anymore. It is a popular saying in sports that nothing breeds failure like success. Sometimes successful people become complacent and even lazy, and do not respect the laws of competition. Developed and successful Western societies are becoming complacent. We need to get smart. And by smart, I mean intelligent in the full sense of the word. Yet we should not try to beat Asia at its own game. This, Im afraid is a battle we have already lost. We are outnumbered and outsmarted. However, the good news is that if we expand the notion of intelligence in the way I am alluding to in this paper, the picture changes. It is not necessary to turn our societies into effective bee-hives of production and busy-ness. This is not our strength. Instead we have to capitalise upon the strong points of Western civilisation and education. It is somewhat ironic that at the time when some are arguing that the Western world is in decline, there is now, more than ever, a need for the kinds of things we excel at. For there is a place in the future for all of us. There needs to be a synthesis of East, West, and the rest. And what are these needs?

The sad reality is that some countries in the East may be making exactly the same mistakes that we have made in the West. The rapid urbanisation, industrialisation and expanded consumerism of East Asia have left the planet reeling from severe environmental pressures that may take centuries to relieve. Even as the world faces a crisis in its banking systems, it pays to remember that China itself has recently faced a similar crisis in its banking systems, although it has been far less transparent in its bailing out its non-performing banks. China has cleaned up its banking and credit systems, but is still heading in the same general direction, tying to drag masses of humanity towards a materialistic, energy-hungry lifestyle which the world simply cannot support. It is a systems problem. Whether it is the US, China, India or Australia, the values of this system are bankrupt. We in the West can stand as an example to those in the East. This is as good a time as any, if it is not already too late. James Lovelock (2008) of Gaia hypothesis fame, has predicted that eighty per cent of the human race will be eliminated from the face of the earth by the year 2100. May I suggest that we do our best to prove him wrong. What the West has to offer Despite the problems that the West is experiencing at present, and the great criticisms that are coming from within and beyond it, we must not throw out the baby with the bathwater. Western civilisation has much to offer the world. As Will Hutton states in China and the West: The Writing on the Wall, China needs the Western ideals of freedom of expression, justice, and even democracy (although not necessarily in Western form) in order for it to move from a manufacturing economy to something akin to a service or knowledge economy. Even Singaporean academic Kishore Mahbubani (2002), a sometimes harsh critic of the West, believes that democracy and features of Western political systems are necessary for developing nations and economies. Part of this is the open thinking that western culture typically features. Daniel Pink (2005) has stated the case well in his book A Whole New Mind. Pink has pointed out that left-brained cognitive processes have generally dominated over

right-brained ways of knowing in modern Western culture. Left-hemisphere cognition is often linguistic and textual in nature (Pink 2005: 1720). The left hemisphere handles logic, sequence, literalness, analysis. The right takes care of synthesis, emotional expression, context, and the big picture (Pink, 2005: 25)iv[iv] Pink argues that the world is changing. What he calls L-directed Thinking (leftbrained) and the jobs requiring such cognitive skills are increasingly being taken up by emerging economies like India and China. Fortunately, argues Pink, the Wests strength in the future will be in R-directed thinking. These right-brained processes involve six high-concept, high touch senses namely design, story (ability to synthesise information into a narrative), symphony (finding integration, the big picture), empathy, play, and meaning (Pink 2005: 65). What will be required in future are skills which more fully balance both sides of the brain. Now, R-Directed Thinking is suddenly determining where were going and how well get there. L-directed aptitudes are still necessary. But theyre no longer sufficient. Instead, the R-Directed Aptitudes artistry, empathy, taking the long view, pursuing the transcendent will increasingly determine who soars and stumbles (Pink, 2005: 27). In short, Pink argues that there has been a shift from the information age to the conceptual age. The driving forces are affluence, technology and globalisation. Those in most demand and most able to prosper in this age will be creators, empathisers, pattern recognisers and meaning makers (Pink 2005: 50). In Australia, there is strong evidence that Pink is correct, with almost thirtyseven per cent of millionaires under the age of forty being involved in creative industries such as architecture, advertising, art, fashion, film, publishing, software, entertainment, TV and video games (Horin 2006). Another key issue is that prosperity in the modern age has freed vast numbers of people from more mundane pursuits and immediate imperatives such as the need

for food or shelter. Millions are seeking transcendence of the mundane, even selfrealisation. Pink (2005) argues that self-realisation is now a quest for the vast majority of the population. For example in the United States the number of meditators has doubled in the last decade, with about ten million adults now practicing it. Fifteen million were practicing yoga in 2005, a doubling from 1999 (Pink 2005: 60). This has lead Pink to suggest that meaning is the new money (Pink 2005: 61). Others agree that critical rationality is no longer enough in the short or long term (Laszlo, Grof & Russell, 2003; Zohar & Marshal 2005). I suggest that we stop dithering with terminology. What we are talking about here is a spiritual shift. Not a return to a medieval theology or a retreat to the ascetics cave, but an incorporation of those necessary and intrinsic aspects of human thinking and experience which have slowly and certainly been leached from our lives and education systems in recent centuries. There is now a growing body of theorists calling for a greater degree of spirituality in business, and in the workplace. One of the first was Peter Senge (1994), who sees personal mastery and the integration of the intuitive, transcendent and rational faculties as being intricately interrelated in the modern workplace. These cognitive processes enhance perception of the connectedness of the world, compassion, and commitment to the whole (Senge 1994: 167). Senge calls for a movement away from selfishness and towards a commitment to something greater than ourselves, including a greater desire to be of service to the world. This incorporates the experience of the awakening of a spiritual power (ibid.: 167-172). Senge argues that this shift is an important part of the learning organisation. There are parallels here with futurist Sohail Inayatullahs (2004) call for spirituality to be the fourth bottom line of business. Inayatullah believes there is already a strong shift towards a more responsible society and corporate world: We are moving from the command-control ego-driven organization to the learning organization to a learning and healing organization. Each step involves seeing the organization less in mechanical terms and more in gaian living terms. The key

organizational asset becomes its human assets, its collective memory and its shared vision (Inayatullah 2004 www.metafuture.org/Articles/spirituality_bottom_line.htm ). For Inayatullah, the spiritual requires three factors. Firstly, there is the need for a relationship with the transcendent both immanent and transcendental (ibid.). Secondly, there is the necessity of meditation and/or prayer. Finally, Inayatullah posits the need to honour the social, which he defines as a relationship with the community, global, or local, a caring for others (ibid.). Likewise, Pink (2005), citing a report from the University of Southern Californias Marshall School of Business called A Spiritual Audit of Corporate America, argues that employees are hungering for spiritual values in the workplace. Pink argues that as more companies come to appreciate this desire, there will be a rise in spirit in business (Pink 2005: 215). Elsewhere (Anthony 2008) I have argued for the necessity for an expanded definition and appreciation of human intelligence in life, business and education, a definition which incorporates the most essential aspects of human spiritual traditions. I have referred to this as integrated intelligence. There is a growing body of evidence that human consciousness is not confined to the head of the individual, and that human beings are connected via a collective consciousness (Braud 2003; Grof 2000; Laszlo et al. 2003). Integrated intelligence is a human beings awareness of this, and the ability to use that intelligence to create a more meaningful life. It is about being successful in a way that transcends mere consumerism and materialism. Integrated Intelligence stands as a possible mediation factor here. If, as Inayatullah implies, spirituality does become the fourth bottom line of modern economics, integrated intelligence could play a crucial role. The focus of Pink, Senge and Inayatullah is primarily short-term, centering on benefits of R-Directed Thinking for workers in Western knowledge economies. Yet, I would like to assert the greatest benefit of integrated intelligence. Let me here quote Peter Russell:

We are all part of the same groundswell. The most important question we need to ask is, how can I put my own life in greater alignment with that groundswell? (Laszlo et al., 2003: ix) There is a tendency for lay people and politicians both East and West to see the other as a threat. It is time to begin to work with the inner dimensions of mind, both in our own lives, and within education systems. We owe it to our children. Former Princeton psychologist David Loye (2004) has pointed out that we can no longer afford to think in terms of a survival of the fittest, hyper-materialistic world. Integrated intelligence is ultimately an affirmation of the extant reality that we are all part of a united humanity. At the very least, humanity is potentially united. I have in my time seen some of the best and worst of both Western and Eastern cultures. It is time for a re-alignment of thinking, both East and West, and a genuine deepening of our ways of knowing. One of the greatest problems which developed from the Enlightenment and the scientific revolution was the philosophical withdrawal of humankind from nature and the cosmos (Tarnas 2000; Wilber 2000). With scientific detachment and reductionism came a loss of connection, and a loss of meaning and purpose. Now we find ourselves in a time where more and more human beings are seeking a greater sense of meaning and purpose. I appreciate the role of professional skeptics like Richard Dawkins (2006). They serve the purpose of highlighting the sometimes madness that passes as spirituality and religion on this planet. But they have thrown out the baby with the bathwater. Not only is an intuitive understanding of meaning and human spirituality economically and socially useful, it is imperative. The reality is that despite the hard work of skeptics, human beings are turning towards transcendence and religious and spiritual matters in ever greater numbers. It is not our responsibility to eliminate that spirituality, as was tried in China under Mao Ze Dong, creating the single most destructive reign of any leadership in human history (Fairbank 2006). It is now time to guide the young towards a healthy expression of the spiritual, and a healthy relationship with their inner worlds.

Critical rationality has created an era of alienation. It is time to begin to restore that connection, and that meaning and purpose - or at least facilitate the active pursuit of it. Intelligence theorist Ken Richardson (2000) notes that human intelligence has accelerated with the development of society and culture, leading to advancement in technology and science that would have been hard to imagine in previous centuries. Would we see a similar acceleration of human intelligence and civilisation if we expanded our concepts of intelligence and ways of knowing and incorporated them into our education systems and ways of life? Would it be the next great leap forward? We can only speculate. The advantages may be great, as I have written previously (Anthony 2005). These may include enhanced capacity to find meaning and purpose in life, as well as counteract information overload and complexity; a move beyond possessive individualism and greed; and a circumvention of the information power and control of institutions and the state. I maintain that personal and collective human transformation is one of the most likely long-term benefits. Integrated intelligence may play a valuable role in the development of society. However, for such benefits to accrue, there needs to be a shift from the knowledge economys focus upon materialism, money and hard power for these are not readily compatible with the kinds of spiritual processes I am writing about. The Futures Perspective I have been heavily involved in Futures Studies for the past six years. I like to call myself an educational futurist, one who still walks to the chalkboard (or computer) each morning and has the privilege of addressing a class of expectant young faces. Futurists do not simply predict the future. In fact prediction trends analysis and extrapolation - is not really the central focus for most futurists. Several recently developed schools of Futures Studies, and most notably Critical Futures Studies, have been influenced by postcritical theory, and attempt to examine the power structures which drive discourses, societies, systems, fields, texts, discussions which affect the future (Slaughter 2006).

A recent development has been the emergence of Post-conventional Futures Studies, a field which has influenced me. These futurists incorporate other ways of knowing, and move beyond empirical and critical analysis to explore the deeper intimacies of discourses, including the intuitive and spiritual. These are futures of dissent, explored by men and women who ask big questions, who stand and challenge the way things are. They include educators (Inayatullah, Bussey, & Milojevic 2006), and are as much inspired by the Eastern sages such as the Buddha, Lao Zi, and the transcendental philosophers Thorough and Emerson, as much as by Newton, Darwin and Heisenberg. I believe that the scientific, the philosophical and spiritual are part of one continuum. They are not mutually exclusive realms which cannot be discussed in the same room. The empirical, the critical and the intuitive are vital aspects of human futures. They are crucial also to education, and therefore the societies that we plan for the future generations of humanity. Practically speaking What does all this mean at a practical level for educators? We all know that if we walk into a classroom and start talking about God or the afterlife we are probably going to create a real mess, and just as likely have half the parents knocking on the principals door after school. So, no, this is not what I mean by returning the deeply meaningful and the spiritual to the classroom. I am not advocating bringing a personal agenda for inculcating a particular religious or philosophical perspective through the classroom door. The process needs to be more considered, more subtle and more respectful than that. The key, I believe is bringing in inner worlds and other ways of knowing into curriculum, and into the classroom. Introducing other ways of knowing into the classroom requires no religious or spiritual jargon. Nor does it necessarily require that students share everything that they experience while exploring the intuitive or being reflective. I use visualisation and quiet time for my students. Notice I did not write

meditation, which unfortunately is a sensitive word for some people and religious groups. Journal writing can also be a great way to get students to honour the intuitive, without necessarily having the need to bear their soul with the class. Using journals immediately after quiet time is a great way to develop the link between the left and right brains, the conscious and subconscious minds. Much of my early days exploring the psyche in my own time involved using a diary, and recording the feelings, images and knowings I got from meditations, as well as dreams and subtle intuitions. Visualisation can be used in a meaningful way. You can ask students to relax, and then describe various scenes before their minds eye. One possibility is to invite students to seek knowledge from their inner mind. During visualisation is a good time to use affirmation positive words and phrases repeated to oneself during quiet time. Visualisation can be a good precursor to engaging in more in depth quiet time. Needless to say, these tools are likely to fail if you try to introduce them in the middle of a semester, after having taught in a completely different way all year. It is best to introduce them very early on in the year, even in the first lesson with a class. I know I am not the only one who uses such methods. One drama teacher I know uses visualisation to help students with imagining themselves being confident during performances. Sharing meaningful anecdotes from your personal life is another way of touching a more profound psycho-spiritual level within the students. Ideally, the themes should be something related to the kinds of profound philosophical and spiritual issues I have mentioned in this paper. Whenever you touch upon the profound or something that connects us with the greater thread of human history, life itself or our dreams and aspirations, opportunities to be meaningful open up. Such themes can include the environment, nature, justice, space exploration, the death penalty, free-market economics, personal success, failure, suicide, illness, triumph, defeat, disability, serious challenges, personal danger Talking about how angry you were at the referee for penalising your favourite team at the weekend

football game isnt going to cut it, Im afraid. And of course it has to be something relevant to the lesson. Many of these themes are already covered in various subjects across the curriculum. The key in bringing forth deeper meaning and the spiritual is connection. Thats why I call it integrated intelligence. It involves an affective appreciation of the thing being explored. In other words, we have to feel it, not merely analyse or measure it for the purpose of meeting curriculum requirements or regurgitating the data for the exams. The world is not likely to be transformed into the serenity a giant Buddhist monastery anytime too soon, and neither is your classroom. I am suggesting small, balanced introductions to inner worlds. Primary schools are the best places to start. However, all this can also be done with senior students. I recently asked a new Form 7 class (18-19 year olds) in Hong Kong if they had ever tried visualisation before. None of them had. Not ever in some 13 years of education! But I didnt let that stop me! We did a visualisation on something deeply meaningful to Hong Kong students the public exam! Slow and steady is the way to go with these things. And you will have to keep your eyes and ears open for feedback. I suggest asking students to openly express their feelings about using these techniques on a regular basis. Finally, you cant fake wisdom or deep understanding of life. So dont even try. You will have to discern what things you feel you have mastery or understanding of, and which ones you do not. Again, in the end, it comes down to being comfortable with yourself and who you are, and with what you really do know. In other words, you use your intuition in the classroom - to know what, when and how deep to teach. And that is something subtle. It is a different way of knowing knowing how to teach. The shifting sands of the twenty-first century These are momentous times for the human race. The shape of the world is

shifting. The dominance of Anglo/white culture is over. The recent credit crisis is more than just a function of greed or poorly regulated banking systems. Nor is it simply a matter of which philosophy takes precedence at any given time. It is a crisis of meaning. What does it mean be human in the modern age? I have friend who runs a small alternative spiritual/health centre in Hong Kong. She bemoans the fact that Hong Kong people are hyper-materialistic, taking their identities as much from their bank balances as from anything else. But she points to a time in Hong Kong when her business boomed. It was the SARS period in mid2003. Suddenly people were asking questions about the meaning of it all. People huddled in fear in their tiny apartment buildings, shielded from the concrete and glass world they had built around them, terrified of a tiny, invisible virus. These are understandings which cannot be found by crunching numbers in machines, or by the machinations of technoscience. They are quintessential questions of being. Things that require us to slow down, or to simply stop and ask, why?. Perhaps more than any other question in these times, we might ask why our lives are being dictated by the quest for more, more, more, and an incessant need to run towards a distant future. And why is it that it takes a crisis before many people ask hard questions about the meaning of it all? Contemplation and meaning cannot simply be afterthoughts in the curriculum. They are an essential part of life. Schooling is meant to equip us to live life in a way that is meaningful. We must bring time into the classroom to reflect upon what it is all about. This entails a degree of vulnerability on behalf of the teacher. Is the teacher to admit her own fears and weaknesses, or her pain at loss and suffering? Is she to confess to the things in this world that she does not understand? Her limitations? And what of those profound life experiences which have granted her wisdom and understanding? Is she to remain silent about these things? Talking about these things requires courage. This is a state of emotional vulnerability which can only be negotiated by an individual with a high degree of psychological and spiritual maturity. In short, wisdom. And wisdom emerges from a deep introspection upon life experience. It emerges from inner worlds.

Carl Jung died in 1958, lamenting his failure to help people see that the human race has a spiritual essence, and that religion and philosophy had become impoverished. Fifty years later, are we any closer to uncovering that buried treasure in the field? If not, how can our education systems be part of the discovery process, and not part of the perpetuation of the problem? References Anthony, (2005). Anthony, (2006). Anthony, (2008) Bolker, A. (1998).Writing Your Dissertation in Fifteen Minutes a Day. New York: Owl Books. Braud, W. (2003). Distant Mental Influence. Charlottesville, VA: Hampton Roads. Crick, F. (1994). Astonishing Hypothesis: The scientific search for the soul. London: Scribner. Dawkins, R., (2006). The God Delusion. London: Houghton Mifflin. Franklin, B. (1999, Winter). Discourse, rationality, and educational research: A historical perspective of RER. Review of Educational Research, 69(4), 347364. Frankl, V. (1985). Mans Search for Meaning. Boston: Washington Square Press. Hutton, Will (2008). The Writing on the Wall: China and the West in the 21st Century. London: Abacus. Fairbank, J. (2006). China: A New History. Cambridge: Belknap Press. Friedman, T., (2006). The World is Flat. London: Allen Lane.

Gardner, H., Kornhaber, M.L., & Wake, W.K., (1996). Intelligence: Multiple Perspectives. New York: Harcourt Brace College. Grof, S. (2000). Psychology of the Future. New York: Suny. Hart, T., (2000. From information to transformation: What the mystics and sages tell us education can be. Encounter: Education for Meaning and Social Justice, 13(3), 14-29. Hernstein, R., & Murry, C., 1994. The Bell Curve: Intelligence and Class Structure in American Life. New York: Free Press. Horin, A., (2006). Young creative types the new mega-rich. Sydney Morning Herald (online). www.smh.com.au/articles/2006/12/10/1165685553911.html?from=top5# Accessed 11.12.06. Huff, T. (2003). The Rise of Early Modern Science. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Hutton, W. (2007). The Writing on the Wall: China and the West in the 21st Century. London: Abacus Inayatullah, S. (2004b). Spirituality as the fourth bottom line. Retrieved October 10, 2007, from www.metafuture.org/ Articles/spirituality_bottom_line.htm Inayatullah, S. (2008). Six pillars: futures thinking for transforming, foresight. Vol. 10, NO. 1 2008, pp. 4-21. Inayatullah, S., Bussey, M., & Milojevic, I. (2006) (eds.) Neo-Humanist Educational Futures, Taipei, Tamkang Uni Press. Jensen, A., 1998. The g Factor. The Science of Mental Ability. Westport: Praeger. Laszlo, E., Grof, S., & Russell, P. (2003). The Consciousness Revolution. Las Vegas:

Elf Rock Loye, D., (2004). Darwin, Maslow, and the Fully Human Theory of Evolution. In: D. Loye, ed. The Great Adventure: Toward a Fully Human Theory of Evolution. New York: State University of New York Press, 20-38. Lovelock, J. (2008). The Revenge of Gaia. New York: Penguin. Maddox, J., (1999). What Remains To Be Discovered. New York: Touchstone. Mahbubani, K., (2002). Can Asians Think? South Royalton: Steer Forth Press Milojevi?, I., (2005). Educational Futures: Dominant and Contesting Visions. New York: Routledge. Moffett, J. (1994). The Universal Schoolhouse. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Oppenheimer, T. (2004). The Flickering Mind. New York: Random House. Pickstone, J. (2000). Ways of Knowing: A New History of Science, Technology and Medicine. Manchester: Manchester University Press. Pink, D.H. (200. A Whole New Mind. New York: Riverhead. Radin, D., (2006). Entangled Minds. New York: Paraview. Ross, G. (1993). The Search for the Pearl. Sydney: ABC Books. Richardson, K. 2000. The Making of Intelligence. London: Phoenix. Slaughter, R. (2006). Beyond the Mundane Towards Post-Conventional Futures Practice. Journal of Futures Studies. Vol 10, no. 4. Pp 15-24. Tarnas, R., (2000). The Passion of the Western Mind. London: Pimlico. Wilber, Ken., (2000). A Brief History of Everything. Boston: Shambhala.

Zohar, D., & Marshall, I. (2005). Spiritual Capital. Bloomsbury 2005.

[i] Of course spiritual ways of knowing have never featured much in modern academia, although an intellectual discussion of them is common to many discourses. ii[ii] Technoscience is science dominated by big business. In such science, scientific knowledge which does not create profit tends to be excluded. ii[iii] Joan Bolkers book Writing Your Dissertation in Fifteen Minutes Day was very helpful, and greatly influenced my understanding of this free-form writing process. I highly recommend the book, even for those in the sciences or using quantitative research methods. You will find it in the references to this paper. ii[iv] It has been pointed out that this kind of left/brained right brained kind of model is simplistic. However there is not space in this paper to elaborate upon this. The model does remain true in essence. Moreover, it serves as a neat way to conceptualise the kinds of cognitive processes I am referring to here.

You might also like

- Freedom and BeyondDocument151 pagesFreedom and Beyondanto.a.fNo ratings yet

- Education For PeaceDocument362 pagesEducation For PeaceAnonymous BPl9TYiZNo ratings yet

- Let's Call It What It Is A Matter of ConscienceDocument33 pagesLet's Call It What It Is A Matter of ConscienceDinh Son MYNo ratings yet

- African Songs and Drum BeatsDocument4 pagesAfrican Songs and Drum BeatsPaul LauNo ratings yet

- Prof Ed 3: The Teacher, and The Community, StudentDocument3 pagesProf Ed 3: The Teacher, and The Community, StudentLaura SumidoNo ratings yet

- Does Psi Exist?Document15 pagesDoes Psi Exist?Pepa GarcíaNo ratings yet

- Philosophy, Education and Their InterdependenceDocument14 pagesPhilosophy, Education and Their InterdependenceV.K. Maheshwari100% (5)

- Teaching Psychology and The Socratic Method: Real Knowledge in A Virtual AgeDocument202 pagesTeaching Psychology and The Socratic Method: Real Knowledge in A Virtual AgeJ Delgado100% (1)

- Benjamin Franklin Transatlantic Fellows Summer Institute AnnouncementDocument5 pagesBenjamin Franklin Transatlantic Fellows Summer Institute AnnouncementUS Embassy Tbilisi, GeorgiaNo ratings yet

- Philosophy of EducationDocument9 pagesPhilosophy of EducationJhong Floreta Montefalcon100% (1)

- Philosophy of Education ExplainedDocument7 pagesPhilosophy of Education Explainedshah jehanNo ratings yet

- Esc3701 Assignment 01Document8 pagesEsc3701 Assignment 01Mbiselo TshabadiraNo ratings yet

- Philosophical Foundation Of: EducationDocument187 pagesPhilosophical Foundation Of: EducationApril Claire Pineda Manlangit100% (1)

- Lesson 1 Philosophical Thoughts On EducationDocument11 pagesLesson 1 Philosophical Thoughts On EducationWennaNo ratings yet

- COMPRE EXAM 2021 EducationalLeadership 1stsem2021 2022Document7 pagesCOMPRE EXAM 2021 EducationalLeadership 1stsem2021 2022Severus S PotterNo ratings yet

- African Philosophy of EducationDocument12 pagesAfrican Philosophy of EducationMbiselo TshabadiraNo ratings yet

- Teaching and Learning from Neuroeducation to Practice: We Are Nature Blended with the Environment. We Adapt and Rediscover Ourselves Together with Others, with More WisdomFrom EverandTeaching and Learning from Neuroeducation to Practice: We Are Nature Blended with the Environment. We Adapt and Rediscover Ourselves Together with Others, with More WisdomNo ratings yet

- History of CurriculumDocument4 pagesHistory of CurriculumKatrina Zoi ApostolNo ratings yet

- Digital Photography 1 Skyline HighSchoolDocument2 pagesDigital Photography 1 Skyline HighSchoolmlgiltnerNo ratings yet

- Bee Pollination 5e Lesson PlanDocument3 pagesBee Pollination 5e Lesson Planapi-338901724100% (1)

- (Research Methods in Linguistics) Aek Phakiti-Experimental Research Methods in Language Learning-Continuum Publishing Corporation (2014) PDFDocument381 pages(Research Methods in Linguistics) Aek Phakiti-Experimental Research Methods in Language Learning-Continuum Publishing Corporation (2014) PDFYaowarut Mengkow100% (1)

- Labor Nursing Care PlanDocument3 pagesLabor Nursing Care PlanGiselle Eclarino100% (9)

- Monica McLean - University and The Pedagogy - Critical Theory and PracticeDocument198 pagesMonica McLean - University and The Pedagogy - Critical Theory and PracticeEdi SubkhanNo ratings yet

- English 7 DLL Q2 Week 8Document6 pagesEnglish 7 DLL Q2 Week 8Anecito Jr. NeriNo ratings yet

- Edf-201-Midterm ExamDocument10 pagesEdf-201-Midterm ExamLoveZel SingleNo ratings yet

- Philosophical Thoughts On EducationDocument31 pagesPhilosophical Thoughts On EducationRyan Marvin Colanag80% (5)

- Philosophy of Education StatementDocument9 pagesPhilosophy of Education StatementLorenzo HallNo ratings yet

- Education and Life's MeaningDocument21 pagesEducation and Life's MeaningReza MohammadiNo ratings yet

- Reflexive Practice: Dialectic Encounter in Psychology & EducationFrom EverandReflexive Practice: Dialectic Encounter in Psychology & EducationNo ratings yet

- Essay Gender InequalityDocument5 pagesEssay Gender Inequalitycjawrknbf100% (1)

- Finished ProjectDocument65 pagesFinished ProjectUGWUEKE CHINYERENo ratings yet

- Allama Iqbals Open University MA Education Course Assignment 1Document8 pagesAllama Iqbals Open University MA Education Course Assignment 1Quran AcademyNo ratings yet

- Hol and PhilosophyDocument8 pagesHol and PhilosophyetohbeberNo ratings yet

- PGCE Introduction To PhilosophyDocument15 pagesPGCE Introduction To PhilosophySiphumeze TitiNo ratings yet

- Humanistic Approaches' To Language Teaching: From Theory To PracticeDocument34 pagesHumanistic Approaches' To Language Teaching: From Theory To PracticesoksokanaNo ratings yet

- Education As Social Invention: Jerome S. BrunerDocument14 pagesEducation As Social Invention: Jerome S. BrunerOlga López PérezNo ratings yet

- Transitional Learning ModelDocument22 pagesTransitional Learning ModelAdriana PopescuNo ratings yet

- Philosophy of Education Paper SsDocument6 pagesPhilosophy of Education Paper Ssapi-310218757No ratings yet

- tHE EDUCATION PHILOSOPHY (Repaired)Document8 pagestHE EDUCATION PHILOSOPHY (Repaired)Nabil IqbalNo ratings yet

- Chapter1 EDUC3 StudentDocument15 pagesChapter1 EDUC3 StudentJaviz BaldiviaNo ratings yet

- Professor G.D. Albear Eastern Illinois University EDF 4450: The Philosophical Dimensions of EducationDocument20 pagesProfessor G.D. Albear Eastern Illinois University EDF 4450: The Philosophical Dimensions of EducationCris Alvin De GuzmanNo ratings yet

- EDUC 106 - Foundations of CurriculumDocument8 pagesEDUC 106 - Foundations of CurriculumLi OchiaNo ratings yet

- Edu 202 Educational Philosophy PaperDocument8 pagesEdu 202 Educational Philosophy Paperapi-322892460No ratings yet

- Hervé Varenne-Culture, Education, AnthropologyDocument23 pagesHervé Varenne-Culture, Education, Anthropologyol giNo ratings yet

- The TeacherDocument51 pagesThe TeacherSonny EstrellaNo ratings yet

- Teaching Thinking Through Philosophy for ChildrenDocument17 pagesTeaching Thinking Through Philosophy for Childrengeovidiella1No ratings yet

- Can America's Schools Be Saved: How the Ideology of American Education Is Destroying ItFrom EverandCan America's Schools Be Saved: How the Ideology of American Education Is Destroying ItNo ratings yet

- Philosophical Thoughts On EducationDocument18 pagesPhilosophical Thoughts On EducationArnold SumadilaNo ratings yet

- A Historic-Critical and Literary-Cultural Approach to the Parables of the Kingdom: A Language Arts Textbook on the New Testament ParablesFrom EverandA Historic-Critical and Literary-Cultural Approach to the Parables of the Kingdom: A Language Arts Textbook on the New Testament ParablesNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 Philosophical Thoughts On EducationDocument15 pagesChapter 1 Philosophical Thoughts On EducationCrystal Janelle TabsingNo ratings yet

- Module 1 and 2Document8 pagesModule 1 and 2Aleli Ann SecretarioNo ratings yet

- SociologyDocument7 pagesSociologyM Ahmad BilalNo ratings yet

- THE LOST SOUL OF SCHOLASTIC STUDY: THE PRACTICAL CORE AND GUIDANCE TO MASTERY OF EVERY SUBJECTFrom EverandTHE LOST SOUL OF SCHOLASTIC STUDY: THE PRACTICAL CORE AND GUIDANCE TO MASTERY OF EVERY SUBJECTNo ratings yet

- Remaking The MindDocument3 pagesRemaking The MindTejadipta Behera100% (1)

- Reflections on Philosophy and EducationDocument6 pagesReflections on Philosophy and EducationArlene Amistad AbingNo ratings yet

- Edu 32-Unit 1-Topic ADocument11 pagesEdu 32-Unit 1-Topic AKristine AlejoNo ratings yet

- Philo of Man-SyllabusDocument10 pagesPhilo of Man-SyllabusMike Sahj BoriborNo ratings yet

- My E-Portfolio in Professional Education IV: Montealto, Klent ODocument33 pagesMy E-Portfolio in Professional Education IV: Montealto, Klent OKlent Omila MontealtoNo ratings yet

- What does it Mean to EducateDocument6 pagesWhat does it Mean to EducateBent BouzidNo ratings yet

- Philosophical Foundation of EducationDocument34 pagesPhilosophical Foundation of EducationKate Reign GabelNo ratings yet

- CDSGA Philosophy (CDSGA 1) Charles Bryan P. Uriarte, Ed.D.: Course Outcome 1Document9 pagesCDSGA Philosophy (CDSGA 1) Charles Bryan P. Uriarte, Ed.D.: Course Outcome 1Bea Bueno100% (1)

- Education in The New NormalDocument3 pagesEducation in The New Normalmelchor FranciscoNo ratings yet

- Symbolic and Non-Symbolic Interactionism, Pillars of EducationDocument24 pagesSymbolic and Non-Symbolic Interactionism, Pillars of EducationShairon palmaNo ratings yet

- Final Poe Lynn McclearyDocument11 pagesFinal Poe Lynn Mcclearyapi-252975184No ratings yet

- Philosophies Crucial for Education During PandemicsDocument3 pagesPhilosophies Crucial for Education During PandemicsRahila DeeNo ratings yet

- Sohail Inayatullah - Spirituality As The Fourth Bottom Line?Document7 pagesSohail Inayatullah - Spirituality As The Fourth Bottom Line?AuLaitRSNo ratings yet

- Mick Collins - Spiritual Intelligence: Evolving Transpersonal Potential Toward Ecological Actualization For A Sustainable FutureDocument15 pagesMick Collins - Spiritual Intelligence: Evolving Transpersonal Potential Toward Ecological Actualization For A Sustainable FutureAuLaitRSNo ratings yet

- Michaeleen C. Maher Et Al - Physiological Concomitants of The Laying-On of Hands: Changes in Healers' and Patients' Tactile SensitivityDocument20 pagesMichaeleen C. Maher Et Al - Physiological Concomitants of The Laying-On of Hands: Changes in Healers' and Patients' Tactile SensitivityAuLaitRSNo ratings yet

- Marcus T. Anthony - A Book Review of David Shenk's The Genius in Us AllDocument6 pagesMarcus T. Anthony - A Book Review of David Shenk's The Genius in Us AllAuLaitRSNo ratings yet

- Marcus Anthony - Futures ResearchDocument23 pagesMarcus Anthony - Futures ResearchAuLaitRSNo ratings yet

- Marcus T. Anthony - Book Review of Allan Combs' Consciousness Explained BetterDocument5 pagesMarcus T. Anthony - Book Review of Allan Combs' Consciousness Explained BetterAuLaitRSNo ratings yet

- Marcus T. Anthony - Secrets of Synchronicity: Heeding The Call of The SoulDocument4 pagesMarcus T. Anthony - Secrets of Synchronicity: Heeding The Call of The SoulAuLaitRSNo ratings yet

- World Futures: The Journal of General EvolutionDocument35 pagesWorld Futures: The Journal of General EvolutionAuLaitRSNo ratings yet

- Think, Blink and The Big StinkDocument4 pagesThink, Blink and The Big StinkMarcusTanthonyNo ratings yet

- Causal Layered Pedagogy - Rethinking Curricula PracticeDocument14 pagesCausal Layered Pedagogy - Rethinking Curricula PracticeGiorgio BertiniNo ratings yet

- David Loye - Optimizing The Obama ShiftDocument8 pagesDavid Loye - Optimizing The Obama ShiftAuLaitRSNo ratings yet

- Ivana Milojevic - Educational Futures: Dominant and Contesting VisionsDocument10 pagesIvana Milojevic - Educational Futures: Dominant and Contesting VisionsAuLaitRSNo ratings yet

- Marcus T. Anthony - The Mechanisation of Mind: A Deconstruction of Two Contemporary Intelligence TheoristsDocument24 pagesMarcus T. Anthony - The Mechanisation of Mind: A Deconstruction of Two Contemporary Intelligence TheoristsAuLaitRSNo ratings yet

- Using Intuitive Intelligence in Everyday LifeDocument26 pagesUsing Intuitive Intelligence in Everyday LifeAuLaitRSNo ratings yet

- Rationality, The Affective and The WoundDocument36 pagesRationality, The Affective and The WoundAuLaitRSNo ratings yet

- The Future, Society and Integrated IntelligenceDocument26 pagesThe Future, Society and Integrated IntelligenceMarcusTanthonyNo ratings yet

- David Loye Et Al - The Great Adventure: Toward A Fully Human Theory of EvolutionDocument4 pagesDavid Loye Et Al - The Great Adventure: Toward A Fully Human Theory of EvolutionAuLaitRSNo ratings yet

- Marcus Anthony - Civilisational Clashes and The ShadowDocument22 pagesMarcus Anthony - Civilisational Clashes and The ShadowAuLaitRSNo ratings yet

- Marcus T. Anthony - Journey To Yan JiDocument16 pagesMarcus T. Anthony - Journey To Yan JiAuLaitRSNo ratings yet

- The Anthony Integrated Learning MethodDocument9 pagesThe Anthony Integrated Learning MethodAuLaitRSNo ratings yet

- Marcus T. Anthony - Deep Futures: Beyond Money and MachinesDocument29 pagesMarcus T. Anthony - Deep Futures: Beyond Money and MachinesAuLaitRSNo ratings yet

- Marcus Anthony - Representations of Integrated Intelligence Within Classical and Contemporary Depictions of Intelligence and Their Educational ImplicationsDocument393 pagesMarcus Anthony - Representations of Integrated Intelligence Within Classical and Contemporary Depictions of Intelligence and Their Educational ImplicationsAuLaitRSNo ratings yet

- Richard Slaughter - Beyond The Mundane - Towards Post-Conventional Futures PracticeDocument10 pagesRichard Slaughter - Beyond The Mundane - Towards Post-Conventional Futures PracticeAuLaitRSNo ratings yet

- Harmonic Circles: A New Futures ToolDocument14 pagesHarmonic Circles: A New Futures ToolAuLaitRSNo ratings yet

- Marcus T. Anthony - Deep Futures and China's EnvironmentDocument23 pagesMarcus T. Anthony - Deep Futures and China's EnvironmentAuLaitRSNo ratings yet

- Marcus Anthony - Towards A Futures Discourse in Mainland ChinaDocument16 pagesMarcus Anthony - Towards A Futures Discourse in Mainland ChinaAuLaitRSNo ratings yet

- Marcus Anthony - Education For Transformation: Integrated Intelligence in The Knowledge Society and BeyondDocument16 pagesMarcus Anthony - Education For Transformation: Integrated Intelligence in The Knowledge Society and BeyondAuLaitRSNo ratings yet

- Marcus Anthony - Visions Without Depth: Michio Kaku's FutureDocument12 pagesMarcus Anthony - Visions Without Depth: Michio Kaku's FutureAuLaitRSNo ratings yet

- Ap-Calculus Bc-Courseoutline To Students-Ms ZhangDocument4 pagesAp-Calculus Bc-Courseoutline To Students-Ms Zhangapi-319065418No ratings yet

- Qip Brochure PHD - 2012 PDFDocument94 pagesQip Brochure PHD - 2012 PDFTushar DeshpandeNo ratings yet

- 1318949413binder2Document38 pages1318949413binder2CoolerAdsNo ratings yet

- They Say I SayDocument3 pagesThey Say I Sayapi-240595359No ratings yet

- 05-OSH Promotion Training & CommunicationDocument38 pages05-OSH Promotion Training & Communicationbuggs115250% (2)

- Engineering Physics 2 Question PapersDocument5 pagesEngineering Physics 2 Question PapersasdfNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan Final - Signs SignalsDocument4 pagesLesson Plan Final - Signs Signalsapi-262631683No ratings yet

- Internship Circular - May 2021Document1 pageInternship Circular - May 2021Baibhav KumarNo ratings yet

- Sample Contract Training ProposalDocument4 pagesSample Contract Training Proposalapi-64007061No ratings yet

- SEO-Optimized title for English lesson on Philippine folktalesDocument6 pagesSEO-Optimized title for English lesson on Philippine folktalesJollyGay Tautoan LadoresNo ratings yet

- Feasibility ProposalDocument3 pagesFeasibility Proposalapi-302337595No ratings yet

- ERAS Personal Statement UCSFDocument3 pagesERAS Personal Statement UCSFmmkassirNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan Checklist: Criteria Yes No N/A CommentsDocument4 pagesLesson Plan Checklist: Criteria Yes No N/A Commentsapi-533285844No ratings yet

- Lesson Plan - TentsDocument10 pagesLesson Plan - Tentsapi-480438960No ratings yet

- Development of Positive Emotions in Children GuideDocument18 pagesDevelopment of Positive Emotions in Children GuideAnonymous 7YP3VYNo ratings yet

- Learner'S Material: Grade 9 Department of Education Republic of The PhilippinesDocument7 pagesLearner'S Material: Grade 9 Department of Education Republic of The PhilippinesReena Theresa RoblesNo ratings yet

- BSW Field ManualDocument92 pagesBSW Field ManualgabrielksdffNo ratings yet

- Hydraulics & Fluid Mechanics Handout 2012-2013Document4 pagesHydraulics & Fluid Mechanics Handout 2012-2013Tushar Gupta0% (1)

- Output 1-FIDP Oral CommunicationDocument2 pagesOutput 1-FIDP Oral Communicationrose ann abdonNo ratings yet

- Case Studies DocumentDocument3 pagesCase Studies DocumentAlvaro BabiloniaNo ratings yet

- CSTP 4 Cortez 5Document5 pagesCSTP 4 Cortez 5api-510049480No ratings yet

- Quantitative ResearchDocument8 pagesQuantitative ResearchHaleema KhalidNo ratings yet