Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Henry, W. Information Technology and Conservation. Getty. 2000

Uploaded by

Trinidad Pasíes Arqueología-ConservaciónCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Henry, W. Information Technology and Conservation. Getty. 2000

Uploaded by

Trinidad Pasíes Arqueología-ConservaciónCopyright:

Available Formats

I

N T

E R N

A T I O

N A L

O R G A N I

Z A T I O N S

Conservati on

T

H

E

S

C

I

E

N

T

I

S

T

R

E

P

A

T

R

I

A

T

I

N

a

t

t

h

e

M

i

l

l

e

n

n

i

u

m

T

h

e

G

e

t

t

y

C

o

n

s

e

r

v

a

t

i

o

n

I

n

s

t

i

t

u

t

e

N

e

w

s

l

e

t

t

e

r

V

o

l

u

m

e

1

5

,

N

u

m

b

e

r

1

2

0

0

0

T O U R I S M

M

N

U

M

E

N

T

S

S

I

T

E

S

A

R

C

H

I

T

E

C

T

U

R

E

C

O

L

L

E

C

T

I

O

N

S

A

R

C

H

I

V

E

S

L

I

B

R

A

R

I

E

P O L I C Y

E T H I C S

E D U C A T I O N

T

E

C

H

N

O

L

O

G

Y

T

H

E

F

T

C

o

n

s

e

r

v

a

t

i

o

n

The Getty

Conservation

Institute

Newsletter

Volume 15, Number 1 2000

The J. Paul Getty Trust

Barry Munitz President and Chief Executive Ofcer

Stephen D. Rountree Executive Vice President and Chief Operating Ofcer

John F. Cooke Executive Vice President, External Affairs

Russell S. Gould Executive Vice President, Finance and Investments

The Getty Conservation Institute

Timothy P. Whalen Director

Jeanne Marie Teutonico Special Advisor to the Director

Group Directors

Kathleen Gaines Administration

Alberto de Tagle Science

Jeanne Marie Teutonico Field Projects

(acting)

Marta de la Torre Information & Communication

Conservation, The Getty Conservation Institute Newsletter

Jeffrey Levin Editor

Joe Molloy Design Consultant

Helen Mauch Graphic Designer

Color West Lithography Inc. Lithography

The Getty Conservation Institute works internationally to advance

conservation practice in the visual artsbroadly interpreted to

include objects, collections, architecture, and sites. The Institute

serves the conservation community through scientic research into

the nature, decay, and treatment of materials; education and train-

ing; model eld projects; and the dissemination of information

through traditional publications and electronic means. In all its

endeavors, the GCI is committed to addressing unanswered ques-

tions and promoting the highest possible standards of conservation.

The Institute is a program of the J. Paul Getty Trust, an international

cultural and philanthropic institution devoted to the visual arts and

the humanities that includes an art museum as well as programs

for education, scholarship, and conservation.

Conservation, The Getty Conservation Institute Newsletter,

is distributed free of charge three times per year, to professionals

in conservation and related elds and to members of the public

concerned about conservation. Back issues of the newsletter,

as well as additional information regarding the activities of the GCI,

can be found on the Institutes home page on the World Wide Web:

http://www.getty.edu/gci

The Getty Conservation Institute

1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 700

Los Angeles, CA 900491684

Telephone: 310 4407325

Fax: 310 4407702

H+vro urr +skrn to write about the impact of information tech-

nology (r+) on conservation, I nd myself reecting, rather, on why

r+ has not had a greater impact on our eld. Computing and net-

working have become entwined in our daily practice, yet one cant

avoid the sense that were not getting as much out of the technology

as we mightor worse, that it is not delivering on its promises.

Rather than reviewing the current state of play, Id like to

oer a few observations on where we need to go from here. Perhaps

because I lack patience and expected our information environment

to evolve more thoroughly than it has to date, I will undoubtedly

seem more a Luddite Cassandra than the avid technology partisan

Ive been in the past. The common thread in these reections is that

technologies evolve more quickly than the social and psychological

adaptations needed to make eective use of them.

The rate at which a notion decays from being novel and inter-

esting to simply being self-evident, if not downright trite, is a

marker of how completely expectations of rapid change now

dominate our experience. To have insisted, a decade or so ago, that

computers were more signicant as communication tools than as

computing machines would have been contentious, but today few

would argueand in the eld of conservation, especially so. While

computation has played an important part in scientic research and

analysis, it haswith the notable exception of imagingmade rela-

tively few signicant inroads into conservation practice. In commu-

nications, however, the impact has been dramatic, especially since

+8y, the year that saw the introduction of the Conservation

Information Network and the Conservation DistList.

It is useful to distinguish (even if the distinction is blurry and

arbitrary) between two major modes of online communication:

interpersonal communications (email, online forums, two-way

conferencing) and information dissemination/retrieval (databases,

most Web sites, online publishing). Both modes are now important

parts of the conservation landscape, though with many users, one

senses greater comfort with the former mode. To judge from

numerous submissions to the Conservation DistList, far too many

professionals prefer relying on direct advice from their colleagues to

looking into the published literature. Despite enormous eorts that

have gone into making access to Art and Archaeology Technical

Abstracts simple and aordable and despite the DistLists frequent

reminders to Search AATA before you post, few participants

appear to take the advice.

Conservation OnLine and Knowledge

Environments

Much of my thinking with regard to technology grows out of my

experience with Conservation OnLine (CoOL), a Web server for

conservation and allied professionals that I initiated in +. CoOL

was originally conceived as a site for gathering much of the large

body of information that falls outside traditional print literature,

and for oering print material in ways that make it more useful

(e.g., full-text searching of articles, hypertext dictionaries, etc.). It

has, to a very small extent, achieved a portion of that aim, captur-

ing, for example, the message trac for a number of conservation-

related email forums and providing unpublished technical reports

(previously published and otherwise), a few online books, and full-

text versions of several print-based newsletters and journals.

At the same timeand not entirely by designCoOL has

taken on an odd role as online home for a number of conservation

organizations, tying them together in a loose network. These orga-

nizations have individual identities (their sites are clearly

autonomous), and at the same time they help compose the virtual

library that is CoOL as a whole. Searches in CoOLs main indexes

will return items from the participant organizations sites, as well as

from CoOL proper. I envision the physical body of CoOL even-

tually dissolving almost entirely, gradually replaced with a virtual

aggregation of information about resources everywhere on the net-

work, and supplementing those resources with local documents

where there are llable gaps. This might be achieved through

remote site indexing software, though the need to gather metadata

sucient to build a sophisticated information facility complicates

matters and will, in most cases, require the participation of remote

siteswhich itself is a good thing, since we are aiming for collabo-

ration in information sharing. A second, less-attractive approach is

that of mirroringcopying entire document webs from remote

sites and making them available on CoOL.

There is another direction in which CoOL might move,

one that complements the concept of CoOL-as-virtual-library.

Looking at CoOL with even the most generous eye, one must

Conservation, The GCI Newsletter

l

Volume 15, Number 1 2000

l

Essays 13

Getting Caught

Up: Information

Technology and

Conservation

By Walter Henry

14 Conservation, The GCI Newsletter

l

Volume 15, Number 1 2000

l

Essays

perceive that in no subject area is there more than a token oering,

enough information to get started, perhaps, but not enough to make

treatment decisions.

The answer, I believe, lies in what have come to be called

knowledge environments (kr). A kr has been dened as an informa-

tion service that: oers structured access to content of all types

relevant to a specic user population; includes opportunities for

continued learning and the transfer of experiential knowledge; is

marketed and sold as an integrated, value-added solution; and is

marketed by a credible, authoritative source.

Built by cooperation between technology specialists, subject

domain specialists, and librarians, the kr attempts to make avail-

ableeither directly or by links to remote resourceseverything a

researcher needs for serious work in a single subject area, organized

by people with advanced subject domain knowledge in such a way as

to make the knowledge useful to specic user communities. Equally

important, it incorporates facilities encouraging ongoing discourse

within the user community.

When I rst encountered the concept of a kr, I thought that

it was exactly what CoOL and similar resources should strive

towarda single locus from which the conservation professional

can locate thorough and authoritative information in any format,

electronic or print. To an extent, CoOL carries some of the incipi-

ent elements of a kr: for example, the inclusion of online forums,

especially the integration of the Conservation DistList, fosters the

development of ongoing communications within the community.

What is lacking is depth and thoroughness of coverage.

In considering knowledge environments for conservation,

the question of scope of coverage is a dicult one. How narrow

should the focus be? While we might build krs that coincide with

existing conservation specialties, I suspect that narrower coverage

will be necessary, perhaps similar in scope to those of AATAs special

supplements.

Building a kr is not a trivial task; funding development and

maintenance will be a challenge. Existing krs are principally

subscription based, a model for which, given the limited economic

resources of our eld, Ive not much optimism. The most likely

avenue for development would seem to be project-based develop-

ment of isolated components of the kr, which are later joined to

form an integrated environment. (An excellent example of a

working kr is tar:http://www.stke.org/ the Signal Transduction

Knowledge Environment, provided by <cite>Science</cite>

[American Association for the Advancement of Science] and

Stanford University.)

Distance Learning

For as long as Ive been in the eld, a driving theme has been the

need for ongoing training opportunities for conservation profes-

sionals. While excellent opportunities for continuing education

exist, there remain obstacles for both the provider and the student,

especially midcareer professionals. Cost, travel, and time away

from the lab are all serious considerations. Of all the applications

of r+ developed in the past decade or two, none have spurred my

optimism more than distance learning. Sitting on the nexus

between information dissemination/retrieval and interpersonal

communication, distance learning leverages r+ to provide instruc-

tion to conservation professionals at remote locations. It oers a

practical solution to each of the problems above and provides

exibility to both teachers and students, enabling professionals

to t continuing education into their work life.

Signicant distance education projects in conservation are

already in place. At the University of Western Sydney, the Nepean

School of Civic Engineering and Environment oers a master of

applied science in material conservation, a three-year part-time

program for those entering the eld, available via distance learning,

as well as through on-site classes. Also in Australia, at the

University of New South Wales, the School of Information,

Library, and Archive Studies provides courses via distance educa-

tion, including preservation administration and preservation and

A two-way interactive videoconferencing system used by Boston conservator

Paul Messier to teach a course via the Internet on the examination and

identication of photographs for students in the Art Conservation

Department at Buffalo State College. The system is an example of one use

of technology for distance education in conservation. Photo: Dan Kushel.

conservation of audiovisual materials. In Canada, the Cultural

Resource Management Program at the University of Victoria

oers distance courses in heritage conservation, conserving historic

structures, and museum-related topics.

Most exciting of the current distance education projects is

that of Paul Messier and Irene Brckle, who put together a two-

way interactive videoconferencing system and used it to teach a

course via the Internet on the examination and identication of

photographs for students at the Art Conservation Department at

Bualo State College. The topic calls for a great deal of student-

teacher interaction and involves subtle visual discrimination, which

must be conveyed between the students in Bualo and Messier in

Boston. As such, the project served as a robust proving ground for

the concept of using information technology for distance education

in conservation. The system appears to have been most eective

and oers hope that this technology will be of great signicance in

conservation education.

For subjects that do not require hands-on experience or

extensive real-time interaction between students and teachers and

that have a reasonably static and well-dened content, Web-based

tutorials seem an excellent means of teaching, especially for courses

that are (or should be) repeated frequently, as online tutorials can be

replayed without incremental cost. Topics in which theoretical

aspects dominate are ideal candidates for this treatment.

Network Collaboration

By now, many conservation professionals have had some experience

serving on committees or task groups conducting their work via

email, and they have experienced both the benets and the frustra-

tions attending this mode of communication. From the earliest days

of electronic mail, users have noted the awkward situations that can

arise from emails lack of those nonlinguistic components that make

face-to-face communication seem so easythe kinesic and aural

cues that constitute phatic communication, the body language that

signals the content of what is not being expressly said (or, in this

case, written).

Despite its speed and glibness-encouraging easiness, email

is not speech, nor is it quite the same as print. There is a distinct

quality to electronic communications, and for the most part our

psychological perspective has not yet adapted to the new mode.

With our lifelong grounding in telephony and printalmost polar

in their sensory and psychological foundationsweve developed

shared expectations of how communication works, expectations

that the new mode undermines. Were developing new behaviors,

maladaptive perhaps, derived from these expectations, which at best

lead to wasted time and eort, at worst to failure of the eort, and

in any case to a gnawing sense that something about this mode of

working just isnt quite right.

Of the problems Ive observed working in online task groups,

the most vexing oneand perhaps the one easiest remediedis a

tendency for the group never to reach closure or consensus or, more

precisely, to fail to realize when consensus has in fact been reached.

This would appear to be rooted in the asynchronous nature of email

and the lack of kinesic cues; one is never quite sure when the

discussion is over. Similarly, there is also a tendency toward false

closure, an attitude among participants that having written on a

subject once, they are nished, when the essence of discourse is that

it runs about, following point upon point before settling into

any resolution.

During the period when the early n+r specications were

developed, members of the Internet Engineering Task Force

(an international group of network designers, operators, vendors,

and researchers concerned with the evolution and operation of the

Internet) created a discursive technology intended to solve this

problem, email forum software geared toward the more-or-less

formal discussion of a large number of issuesin this case, specic

clauses of a proposed specication and voting at various stages in

the discussion. While this seemed to work well, most discussions

are less structured than those. Nevertheless, the idea showed

promise, and other collaborative tools, notably collaborative author-

ing tools, have since been developed. Most are designed for use

within an intranet, but Internet-based systems are entering the

market, and some may be helpful for collaboration among conserva-

tion professionals.

These technological solutions, however, beg the question.

The point is that we have not yet adapted socially and psychologi-

cally to the new media. An obvious quick x is for a leader to declare

a deadline and to announce the nal consensus, but in practice the

oft-noted democratizing proclivity of network discourse seems to

militate against that. In practice, more often than I can remember,

such discussions are resolved oine, typically face-to-face or by

phone, with participants asking each other, Are we done? One

assumes that with time, our vocabulary of online conventions will

grow suciently to make such aberrations unnecessary.

Electronic Texts

Computer communication is a supremely eective information

discovery tool, but reading substantial bodies of text from a display

screen is for most readers not compatible with careful, considered

readingthe kind needed to transform information into knowl-

edge. Alex Pang, a colleague at Stanford, commented that when

he assigned an all-Web reading list, he noted a marked superciality

Conservation, The GCI Newsletter

l

Volume 15, Number 1 2000

l

Essays 15

in his students reading. When he instituted a print-on-demand

system, encouraging his students to read from hard copy, the situa-

tion improved.

This phenomenon is common, and it is probably a factor in

the continuous retreat of the paperless oce. Indeed, when

I watch people reading Web pages online, I notice that they tend

to scroll quickly, scanning rather than reading. Ease of scrolling

encourages this mode of acquisition, rewarding rapid scanning

with quickly found answers, an electronic form of speed reading.

The implications for information management in technical

elds are clear. Im no fan of presentation-oriented document

formats, but I concede that when presenting complex, hard-to-read

materials, online services should oer print-friendly versions in

more or lessplatform-independent formats such as rnr, at least

until readers better adapt to online presentation. In the longer term,

we must relearn to read.

Documentation

Elsewhere I have written about some of the technical challenges

facing those who would construct database and document author-

ing systems to support conservation treatment and examination

documentation. Beyond those technical issues, however, lies a far

more intriguing problem. A colleague, Lisa Mibach, pointed out

that conservators spend much of their time looking intently at

objects, and that having to lift the eyes and hands to use a computer

breaks the concentration enough to seriously interfere with the

examination.

Over time, humans have learned to integrate handwriting so

completely into our behavior that writing while looking does not

introduce a cognitive disjuncture. But we have yet to adapt to com-

puter input in the same way. Indeed, with the current conguration

of computing devices, it would seem unlikely that we will ever fully

adapt, although more recent handheld computers may be moving in

the right direction.

In the past year or two, voice recognition technology has made

great advances, and it is now possible to buy consumer-level dicta-

tion hardware and software that are accurate and convenient enough

to suggest that it will not be many more years before conservators

can dictate treatment reports at the bench and have them converted

to machine-readable text in real time. When that is achieved, com-

puter-based documentation systems will cease being mere record

storehouses and will begin, at last, to facilitate the creation of richly

detailed examination and treatment records.

Walter Henry, a conservator by training, is

acting head of media preservation at Stanford

University Libraries. Since 1987 he has

served as moderator of Conservation DistList,

an electronic forum on the conservation of

library, archive, and museum materials.

He also continues to administer Conservation

OnLine. He has been an associate editor of

Journal of the American Institute for

Conservation since 1996.

The author wishes to acknowledge the following sources in the preparation of this article: Creating

Knowledge Environments, Information about Information Service Brieng, vol. +, no. , July +,

+8, Outsell, Inc., quoted in Leveraging the Intranet in Knowledge Management, by Mary Lee

Kennedy, Director, Information Services, Microsoft Corporation; Photography Conservation

Training Via Videoconference: A Project Report [abstract], by Irene Brckle and Paul Messier,

Electronic Media Group, AIC Annual Meeting, St. Louis, June ++, +

tar:http://aic.stanford.edu/conspec/emg/st_louis_meeting.html.

Resources

on the Internet

Many resources relating

to conservation can be

found on the Internet.

The National Center for

Preservation Technology

and Training (cr++)

maintains a comprehensive

electronic clearinghouse

of preservation Internet

resources on its own Web

site, which provides infor-

mation on other Web sites,

list serves, usenet groups,

and additional resources

related to the eld.

To search the cr++

clearinghouse, go to:

http://www.ncptt.nps.gov/pir/

16 Conservation, The GCI Newsletter

l

Volume 15, Number 1 2000

l

Essays

W

a

y

n

e

V

a

n

d

e

r

k

u

i

l

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Wressning F. Conservation and Tourism. 1999Document5 pagesWressning F. Conservation and Tourism. 1999Trinidad Pasíes Arqueología-ConservaciónNo ratings yet

- Druzik, J. Research On Museum Lighting. GCI. 2007Document6 pagesDruzik, J. Research On Museum Lighting. GCI. 2007Trinidad Pasíes Arqueología-ConservaciónNo ratings yet

- Godonou, A. Documentation in Service of Conservation. 1999Document6 pagesGodonou, A. Documentation in Service of Conservation. 1999Trinidad Pasíes Arqueología-ConservaciónNo ratings yet

- Nardi, R. New Approach To Conservation Education. 1999Document8 pagesNardi, R. New Approach To Conservation Education. 1999Trinidad Pasíes Arqueología-ConservaciónNo ratings yet

- Milner, C. Conservation in Contemporary Context. 1999Document7 pagesMilner, C. Conservation in Contemporary Context. 1999Trinidad Pasíes Arqueología-ConservaciónNo ratings yet

- De Guichen, G. Preventive Conservation. 1999Document4 pagesDe Guichen, G. Preventive Conservation. 1999Trinidad Pasíes Arqueología-Conservación0% (1)

- Krebs, M. Strategy Preventive Conservation Training. 1999Document5 pagesKrebs, M. Strategy Preventive Conservation Training. 1999Trinidad Pasíes Arqueología-ConservaciónNo ratings yet

- Kissel, E. The Restorer. Key Player in Preventive Conservation. 1999Document8 pagesKissel, E. The Restorer. Key Player in Preventive Conservation. 1999Trinidad Pasíes Arqueología-ConservaciónNo ratings yet

- Van Giffen, A. Conservation of Islamic Jug. 2011Document5 pagesVan Giffen, A. Conservation of Islamic Jug. 2011Trinidad Pasíes Arqueología-ConservaciónNo ratings yet

- Van Giffen, A. Conservation of Venetian Globet. 2011Document2 pagesVan Giffen, A. Conservation of Venetian Globet. 2011Trinidad Pasíes Arqueología-ConservaciónNo ratings yet

- Van Giffen, A. Glass Corrosion. Weathering. 2011Document3 pagesVan Giffen, A. Glass Corrosion. Weathering. 2011Trinidad Pasíes Arqueología-ConservaciónNo ratings yet

- Blanc He Gorge, E. Preventive Conservation Antonio Vivevel Museum. 1999Document7 pagesBlanc He Gorge, E. Preventive Conservation Antonio Vivevel Museum. 1999Trinidad Pasíes Arqueología-ConservaciónNo ratings yet

- Eremin, K. y Walton, M. Analysis of Glass Mia GCI. 2010Document4 pagesEremin, K. y Walton, M. Analysis of Glass Mia GCI. 2010Trinidad Pasíes Arqueología-ConservaciónNo ratings yet

- Risser, E. New Technique Casting Missing Areas in Glass. 1997Document9 pagesRisser, E. New Technique Casting Missing Areas in Glass. 1997Trinidad Pasíes Arqueología-ConservaciónNo ratings yet

- Levin, J. Nefertari Saving The Queen. 1992Document8 pagesLevin, J. Nefertari Saving The Queen. 1992Trinidad Pasíes Arqueología-ConservaciónNo ratings yet

- VVAA. Conservation Decorated Architectural Surfaces. GCI. 2010Document29 pagesVVAA. Conservation Decorated Architectural Surfaces. GCI. 2010Trinidad Pasíes Arqueología-Conservación100% (2)

- VVAA. A Chemical Hygiene PlanDocument8 pagesVVAA. A Chemical Hygiene PlanTrinidad Pasíes Arqueología-ConservaciónNo ratings yet

- Van Giffen, A. Medieval Biconical Bottle. 2011Document6 pagesVan Giffen, A. Medieval Biconical Bottle. 2011Trinidad Pasíes Arqueología-ConservaciónNo ratings yet

- MacCannell D. Cultural Turism. Getty. 2000Document6 pagesMacCannell D. Cultural Turism. Getty. 2000Trinidad Pasíes Arqueología-ConservaciónNo ratings yet

- VVAA. Rock Art. Gci. 2006Document32 pagesVVAA. Rock Art. Gci. 2006Trinidad Pasíes Arqueología-Conservación100% (1)

- Abbas, H. Deterioration Rock Inscriptions Egypt. 2011Document15 pagesAbbas, H. Deterioration Rock Inscriptions Egypt. 2011Trinidad Pasíes Arqueología-ConservaciónNo ratings yet

- Lewis, A. Et Al. Discuss Reconstruction Stone Vessel. 2011Document9 pagesLewis, A. Et Al. Discuss Reconstruction Stone Vessel. 2011Trinidad Pasíes Arqueología-ConservaciónNo ratings yet

- Fischer, C. y Bahamondez M. Moai. Environmental Monitoring and Conservation Mission. 2011Document15 pagesFischer, C. y Bahamondez M. Moai. Environmental Monitoring and Conservation Mission. 2011Trinidad Pasíes Arqueología-ConservaciónNo ratings yet

- Torraca, G. The Scientist in Conservation. Getty. 1999Document6 pagesTorraca, G. The Scientist in Conservation. Getty. 1999Trinidad Pasíes Arqueología-ConservaciónNo ratings yet

- Lewis, A. Et Al. Research Resin Mummy. 2010Document4 pagesLewis, A. Et Al. Research Resin Mummy. 2010Trinidad Pasíes Arqueología-ConservaciónNo ratings yet

- Doehne, E. Travertine Stone at The Getty Center. 1996Document4 pagesDoehne, E. Travertine Stone at The Getty Center. 1996Trinidad Pasíes Arqueología-ConservaciónNo ratings yet

- Standley, N. The Great Mural. Conserving The Rock Art of Baja California. 1996Document9 pagesStandley, N. The Great Mural. Conserving The Rock Art of Baja California. 1996Trinidad Pasíes Arqueología-ConservaciónNo ratings yet

- Odegaard, N. Collaboration in Preservation of Etnograhic and Archaeological Objects. GCI. 2005Document6 pagesOdegaard, N. Collaboration in Preservation of Etnograhic and Archaeological Objects. GCI. 2005Trinidad Pasíes Arqueología-ConservaciónNo ratings yet

- Lewis, A. Et Al. Preliminary Results Cocodrile Mummy. 2010Document7 pagesLewis, A. Et Al. Preliminary Results Cocodrile Mummy. 2010Trinidad Pasíes Arqueología-ConservaciónNo ratings yet

- Lewis, A. Et Al. CT Scanning Cocodrile Mummies. 2010Document7 pagesLewis, A. Et Al. CT Scanning Cocodrile Mummies. 2010Trinidad Pasíes Arqueología-ConservaciónNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Unit 6B - PassiveDocument18 pagesUnit 6B - PassiveDavid EstrellaNo ratings yet

- Pinterest or Thinterest Social Comparison and Body Image On Social MediaDocument9 pagesPinterest or Thinterest Social Comparison and Body Image On Social MediaAgung IkhssaniNo ratings yet

- 02 Laboratory Exercise 1Document2 pages02 Laboratory Exercise 1Mico Bryan BurgosNo ratings yet

- The Abcs of Edi: A Comprehensive Guide For 3Pl Warehouses: White PaperDocument12 pagesThe Abcs of Edi: A Comprehensive Guide For 3Pl Warehouses: White PaperIgor SangulinNo ratings yet

- Design and Analysis of DC-DC Boost Converter: September 2016Document5 pagesDesign and Analysis of DC-DC Boost Converter: September 2016Anonymous Vfp0ztNo ratings yet

- -4618918اسئلة مدني فحص التخطيط مع الأجوبة من د. طارق الشامي & م. أحمد هنداويDocument35 pages-4618918اسئلة مدني فحص التخطيط مع الأجوبة من د. طارق الشامي & م. أحمد هنداويAboalmaail Alamin100% (1)

- IRJ November 2021Document44 pagesIRJ November 2021sigma gaya100% (1)

- Grade 7 Hazards and RisksDocument27 pagesGrade 7 Hazards and RisksPEMAR ACOSTA75% (4)

- Diagnostic Test Everybody Up 5, 2020Document2 pagesDiagnostic Test Everybody Up 5, 2020George Paz0% (1)

- Smashing HTML5 (Smashing Magazine Book Series)Document371 pagesSmashing HTML5 (Smashing Magazine Book Series)tommannanchery211No ratings yet

- Zimbabwe - Youth and Tourism Enhancement Project - National Tourism Masterplan - EOIDocument1 pageZimbabwe - Youth and Tourism Enhancement Project - National Tourism Masterplan - EOIcarlton.mamire.gtNo ratings yet

- 3-CHAPTER-1 - Edited v1Document32 pages3-CHAPTER-1 - Edited v1Michael Jaye RiblezaNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Direct and Indirect Pulp CappingDocument9 pagesJurnal Direct and Indirect Pulp Cappingninis anisaNo ratings yet

- Test 1801 New Holland TS100 DieselDocument5 pagesTest 1801 New Holland TS100 DieselAPENTOMOTIKI WEST GREECENo ratings yet

- Tourism and GastronomyDocument245 pagesTourism and GastronomySakurel ZenzeiNo ratings yet

- Suggestions On How To Prepare The PortfolioDocument2 pagesSuggestions On How To Prepare The PortfolioPeter Pitas DalocdocNo ratings yet

- Class 12 Unit-2 2022Document4 pagesClass 12 Unit-2 2022Shreya mauryaNo ratings yet

- CFodrey CVDocument12 pagesCFodrey CVCrystal N FodreyNo ratings yet

- Case Studies InterviewDocument7 pagesCase Studies Interviewxuyq_richard8867100% (2)

- ETSI EG 202 057-4 Speech Processing - Transmission and Quality Aspects (STQ) - Umbrales de CalidaDocument34 pagesETSI EG 202 057-4 Speech Processing - Transmission and Quality Aspects (STQ) - Umbrales de Calidat3rdacNo ratings yet

- MHR Common SFX and LimitsDocument2 pagesMHR Common SFX and LimitsJeferson MoreiraNo ratings yet

- Dreizler EDocument265 pagesDreizler ERobis OliveiraNo ratings yet

- Datasheet of STS 6000K H1 GCADocument1 pageDatasheet of STS 6000K H1 GCAHome AutomatingNo ratings yet

- Data SheetDocument14 pagesData SheetAnonymous R8ZXABkNo ratings yet

- Awo, Part I by Awo Fa'lokun FatunmbiDocument7 pagesAwo, Part I by Awo Fa'lokun FatunmbiodeNo ratings yet

- SeaTrust HullScan UserGuide Consolidated Rev01Document203 pagesSeaTrust HullScan UserGuide Consolidated Rev01bong2rmNo ratings yet

- JLPT Application Form Method-December 2023Document3 pagesJLPT Application Form Method-December 2023Sajiri KamatNo ratings yet

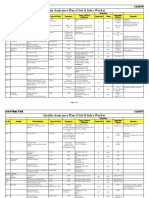

- Quality Assurance Plan - CivilDocument11 pagesQuality Assurance Plan - CivilDeviPrasadNathNo ratings yet

- Service M5X0G SMDocument98 pagesService M5X0G SMbiancocfNo ratings yet

- 2015 Grade 4 English HL Test MemoDocument5 pages2015 Grade 4 English HL Test MemorosinaNo ratings yet