Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Deconstructionism - Flavia Loscialpo

Uploaded by

Edith LázárOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Deconstructionism - Flavia Loscialpo

Uploaded by

Edith LázárCopyright:

Available Formats

Fa s hion a nd P hilo s o phi c al D e c on stru ction: a Fa s hion inde c on stru ction Flavia Loscialpo

A b stra ct The paper explores the concept of deconstruction and its implications in contemporary fashion. Since its early popularization, in the 1960s, philosophical deconstruction has traversed different soils, from literature to cinema, from architecture to all areas of design. The possibility of a fertile dialogue between deconstruction and diverse domains of human creation is ensured by the asystematic and transversal character of deconstruction itself, which does not belong to a sole specific discipline, and neither can be conceived as a body of specialistic knowledge. When, in the early 1980s, a new generation of independent thinking designers made its appearance on the fashion scenario, it seemed to incarnate a sort of distress in comparison to the fashion of the times. Influenced by the minimalism of their own art and culture, designers Rei Kawakubo, Yohji Yamamoto, Issey Miyake and, later in the decade, the Belgian Martin Margiela, Ann Demeulemeester and Dries Van Noten pioneered what can legitimately be considered a fashion revolution. By the practicing of deconstructions, such designers have disinterred the mechanics of the dress structure and, with them, the mechanisms of fascinations that haunt fashion. The disruptive force of their works resided not only in their undoing the structure of a specific garment, in renouncing to finish, in working through subtractions or displacements, but also, and above all, in rethinking the function and the meaning of the garment itself. With this, they inaugurated a fertile reflection questioning the relationship between the body and the garment, as well as the concept of body itself. Just like Derridas deconstruction, the creation of a piece via deconstruction implicitly raises questions about our assumptions regarding fashion, showing that there is no objective standpoint, outside history, from which ideas, old concepts, as well as their manifestations, can be dismantled, repeated or reinterpreted. This constant dialogue with the past is precisely what allows designers practicing deconstruction to point to new landscapes. . K e y Word s: Deconstruction, Derrida, distress, mode destroy, mechanisms of fascination, body, consumer culture, history. ***** Title of eBook Chapter ______________________________________________________________

1. Th e g er m s of de c on stru ction

Deconstruction, as a philosophical practice, has spread its influence far beyond the borders of philosophy and academic speculation. Since its early popularization in the 1960s, it has traversed different soils, from literature to cinema, from architecture to all areas of design. The term deconstruction possesses a particular philosophical pedigree, and its history of effects has been widely documented and meticulously investigated. This is not merely casual. Well known is in fact the resistance of Jacques Derrida, father of deconstruction, to provide a definition of it, and thus to surrender to the original Platonic question trying to fix the essence (ti esti) of the things, that has long permeated Western metaphysics. Rather than being a methodology, an analysis, or a critique, deconstruction is eminently an activity, that is, a reading of the text. The a-systematic character of deconstructive reading emerges in its putting into question, and in re-thinking, a series of opposing terms, such as subjectobject, nature-culture, presence-absence, inside-outside, which are all elements of a conceptual metaphysical hierarchy.1 The deconstruction pursued by Derrida is strictly connected to another disrupting philosophical project, that is, the phenomenological destruction. In the philosophical

tradition, destruction (Destruktion), as Heidegger explains, is a peculiar disinterring and bringing to light the un-thought and un-said in a way that recalls an authentic experience of what is originary.2 The Heideggerian destruction and the deconstruction outlined by Derrida ultimately converge, fused by the same intention of mining the petrified layers of metaphysics that have for centuries dominated philosophy. Nevertheless, the deconstructive practice never finds an end, and is rather an open and complex way of proceeding.3 In an interview released to Christopher Norris in 1988, on the occasion of the International Symposium on Deconstruction (London), Derrida says: deconstruction goes through certain social and political structures, meeting with resistance and displacing institutions as it does so. I think that in these forms of art, and in any architecture, to deconstruct traditional sanctions theoretical, philosophical, cultural effectively, you have to displaceI would say solid structures, not only in the sense of material structures, but solid in the sense of cultural, pedagogical, political, economic structures.4 Spoken, written or visual language could in fact be the embodiment of forms of power and hierarchical systems of thought that have become so embedded in the language that are now even hardly recognizable. The task of 2 Name and Surname of Author(s) ______________________________________________________________ deconstruction is therefore to question the authoritarian foundations on which these structures are based, disclosing new possibilities of signification and representation. Among the fixed binary oppositions that deconstruction seeks to undermine are language-thought, practice-theory, literature-criticism, signifier-signified. According to Derrida, the signifier and signified, in fact, do not give birth to a consistent set of correspondences, for the meaning is never found in the signifier in its full being: it is within it, and yet is also absent.5 The ideas conveyed by deconstruction have profoundly influenced literature, related design areas of architecture, graphic design, new media, and film theory. Derridas relationship with the domain of aesthetics runs indeed alongside his deconstructive work practiced on contemporary philosophy: at first with The Truth in Painting (1981), then with Memoires of the Blind (1990), and finally with La connaissance des textes. Lecture dun manuscrit illisible (2001), written with Simon Hantai e Jean-Luc Nancy. However, it is only with Spectres of Marx (1993) that Derridas idea of a spectral aesthetics achieves its full development. Through the decades, the possibility of a fertile dialogue between deconstruction and many diverse areas of human creation has been encouraged and ensured by the asystematic and transversal character of deconstruction itself, which does not belong to a sole specific discipline, and neither can be conceived as a specialistic knowledge. In the words of Derrida, in fact, deconstruction, is not a unitary concept, although it is often deployed in that way, a usage that I found very disconcertingSometimes I prefer to say deconstructions in the plural, just to be careful about the heterogeneity and the multiplicity, the necessary multiplicity of gestures, of fields, of styles. Since it is not a system, not a method, it cannot be homogenized. Since it takes the singularity of every context into account, Deconstruction is different from one context to another.6

2. A fa shion in-de c on stru ction

In the early 1980s a new breed of independent thinking and largely Japanese designers made its appearance on the fashion scenario, transforming

it deeply. Influenced by the minimalism of their own art and culture, designers 3 Title of eBook Chapter ______________________________________________________________ Yohji Yamamoto, Rei Kawakubo (Commes Des garcons),7 Issey Miyake and, later in the decade, the Belgian Martin Margiela, Ann Demeulemeester and Dries Van Noten largely pioneered the fashion revolution. As recalled by fashion experts, 1981 is the year in which both Yamamoto e Kawakubo showed for the first time their collection in Paris. Their appearance forced the representatives of the worlds press to examine their consciences.8 Rejecting every clichd notion of what glamour should be, or the fashionable silhouette should look like, they disclosed in fact a new approach to clothing in the post-industrial, late 20th century society. Their major contribution consisted, and still consists, in their endless challenging the relationship between memory and modernity, enduring and ephemeral. At first, the austere, demure, often second hand look of their creations induced some journalists to describe it as post-punk, or grunge. Nevertheless, the disruptive force of their works resided not only in their undoing the structure of a specific garment, in renouncing to finish, in working through subtractions or displacements, but also, and above all, in rethinking the function and the meaning of the garment itself. They inaugurated, thus, a fertile reflection that questioned the relationship between the body and the garment, as well as the concept of body itself. Almost a decade later, in July 1993, an article on deconstructionist fashion appeared in The New York Times, with the intention of clarifying the origin and the directionality of this new movement, of such a still mysterious avantgarde. A sartorial family tree immediately emerged: Comme des Garcons' Rei Kawakubo is mom; Jean-Paul Gaultier is dad. Mr. Margiela is the favored son. And Coco Chanel is that distant relative everyone dreads a visit from, but once she's in town, realizes they have of a lot in common after all.9 Even before the word deconstruction began to circulate in the fashion landscape, it became clear that some designers were already reacting and measuring themselves against the parameters that at the time were dominating fashion.10 In 1978, for instance, Rei Kawakubo produced for Commes des Garons a catwalk collection that included a range of black severe coats, tabards, and bandage hats.11 Subsequently, in 1981, Yohji Yamamoto expressed a way of dressing that constituted an alternative to the mainstream fashion: the clothes were sparse, monochrome, anti-status and timeless; knitwear resulted in sculptural pieces with holes, in mis-buttoning to pull and distort the fabric, in ragged and non conformist shapes, that were in complete contrast, in the form, with the glamorous, sexy, power clothes of the 1980s. Revolting against the excessive attitude and the little imagination that were 4 Name and Surname of Author(s) ______________________________________________________________ anaesthetizing fashion, Margiela reworked old clothes and the most disparate materials, and for his first Parisian show (Summer 1989) choose a parking garage. Models had blackened eyes, wan faces. They walked through red paint and left gory footprints across white paper. Later on, for his 1989-1990 Winter collection, he used the same foot-printed paper to make jackets and waistcoats. As Margiela recalls, this first show caused strange reactions, or no reactions at all. He says, "we were working one year, and wanted a concept. It's a big word, but if you see what happened afterward, after five years, I think we can call it that".12 Often labelled as anti-fashion, or the death of fashion, the works of the deconstructivist designers incarnated a sort of distress in respect to the

mainstream fashion of the late 1980s. Nevertheless, just as Margielas former teacher at the Academie Royale des Beaux Atrs, Ms. Poumaillou, insists, instead of killing fashion, which is what some thought he was doing, he was making an apology".13 Making a parody of the already excessive and, in a certain extent, orthodox fashion of the times would have in fact been redundant. By the making of deconstructions and reproductions, Margielas work rather concentrated in disinterring the mechanics of the dress structure and, with them, the mechanisms of fascinations that haunt fashion. The way of proceeding adopted by Kawakubo, Margiela, Yamamoto could bear associations with the sub-cultural fashion movements of the 1980s. The idea of cutting up clothes refers back to the ripped t-shirts of the punks and the subsequent street style of slicing jeans with razor blades. Nevertheless, the work of the deconstructivist designers goes much further. Far from resulting in a mere collage, or in recycled post-punk, or even in some post-nuclear survivalism, deconstruction fashion, or mode destroy, as Elizabeth Wilson clarifies, is definitely a more intellectual approach, which literally unpicked fashion, exposing its operations, its relations to the body and at the same time to the structures and discourses of fashion.14Deconstruction fashion, which is always already in-deconstruction itself, involves in fact a thorough consideration of fashion's debt to its own history, to critical thought, to temporality and the modern condition. 3. T he de c o n stru cted body The peculiar way in which deconstructivist designers question fashion, through subtractions, replications and deconstructions, sounds well like a whisper, in which what is not overtly said is both a consequence of and, at the same time, a condition for saying. Philosophically speaking, the force of deconstructive thinking can only be realized through the conditions of its dissemination. Similarly, for more than two decades, their creations have 5 Title of eBook Chapter ______________________________________________________________ unfailingly confronted themselves with the parameters that have determined and still determine fashion today. In fashion, a complexity of tensions and meanings, not only relative to the dimension of clothing, becomes manifest and accessible. At the centre of this complexity there is always the body, in all the modalities of its being-in-theworld, of its self-representing, of its disguising, of its measuring and conflicting with stereotypes and mythologies. The dressed body represents therefore the physical and cultural territory where the visible and sensible performance of our identity takes place. What deconstruction fashion tends to show is how absence, dislocation, and reproduction affect the relationship between the individual body and a frozen idealization of it, as well as the one between the objects and their multiple meanings. Significantly, in the early 1980s the work of deconstructivist designers was considered a direct attack on western ideas of the body shaping. Their designs, apparently shapeless, were radically unfamiliar. But such a new shapeless shape was subtly threatening the parameters prescribing the exaggerated silhouette of the mainstream fashion of the times. When it first came to prominence, Kawakubos oeuvre never seemed to be inspired by a particular idea of body-type or sexuality: it was simply neutral, neither revealing nor accentuating the shape of a body. As Deyan Sudjic underlines, her creations neither draw attention to the form of the body, nor try to make the body conform to a preconceived shape; instead, the texture, layering and form of the clothes are regarded as objects of interest in themselves.15At the same time, Yohji Yamamoto, inspired by images of workers belonging to another age, was disclosing a new possibility in respect to the self enclosed horizon constituted by prior representations of the body. Illustrating Yamamotos way of proceeding, Franois Baudot remarks the importance of this overturning:

in a society that glorifies and exalts the body and exposes it to view, Yohji has invented a new code of modesty.16 By playing with an idealized body, deconstruction fashion challenged the traditional oppositions between a subject and an object, an inside and an outside. It finally showed that the subjectivity is not a datum, but is rather continuously articulated, through time and space, according to different myths, needs, affirmations, or just oblivion. Not by chance, a recurring motif in deconstruction fashion is the reversal of the relation between the body and the garment. Kawakubos Comme des Garons S/S 1997 collection, called Dress Becomes Body, masterfully exemplifies such operation: the lumps and bumps emerging from beneath the fabrics seem to be forcing the boundaries between the body and the dress, and to shape a different possibility of articulating the modern subjecthood.17 No longer contained or morphed by its standardized and rigid representation, the body begins to react to the garment; it animates it and finally encompasses it. Nevertheless, such a possibility remains just one among the many that can be 6 Name and Surname of Author(s) ______________________________________________________________ and are yet to be drawn. As theoretical indicators, these conceptual designs hold an immense critical importance, as they show that any departure from the perfection of some crystallized paradigm should not be understood as insufficiency or limit. The reflection upon the border, the containment, the inside/outside demarcation is crucial for the deconstructivist designers, whose contribution regularly manifests itself in overturning this supposedly pacific relation. Indeed, a staple of Margielas aesthetics is the recreated tailors dummy, worn as a waistcoat directly over the skin, which tends to reverse the relationship between the garment and the wearer: the body actually wears the dummy. In other occasions, as in the enlarged collection derived from doll clothes, Margielas work explicitly refers to the problematic of the standardized body, for it ironically unveils the inherent disproportions of garments belonging to a body metonymically calling into question an idealized body of the doll. Several collections (A/W 1994-1995, S/S 1999) contain in fact pieces that are reproduced from a dolls wardrobe and are subsequently enlarged to human proportions, so that the disproportion of the details is evident in the enlargement. This procedure results in gigantic zippers, push buttons, oversized patterns and extreme thick wool. In such a way, Margielas practice of fashion questions the relationship between the means and the representation of the means, between realism and real, between reality and representation. The clothes produced for the line a Dolls Wardrobe are faithfully translated from doll proportions to human size, with the effect of producing an exaggeration of the details. As Alistair ONeill highlights, Margiela points to the slippage between seeing an outfit and wearing it by showing how something is lost and something poetic is found in the translation.18By reversing the relation between body and clothes, and by playing with an idealized body, Margiela problematizes the traditional oppositions between subject and object, body and garment. Thus, Margielas peculiar manipulating, as Barbara Vinken points out, contributes to revealing how fashion brought the ideal to life, an ideal which, however, was such located out of time, untouched, like the dummy, by the decline to which the flesh is subject.19 4. E thi c s of de c on stru ction fa shion The disposition to seek, like the philosophical project of deconstruction, to rethink the formal logic of dress itself20 has become, in the last three decades, the motif that characteristically defines the practice of fashion pursued by deconstructivist designers. Fashion, art, and a critical reflection on consumer culture are strictly intertwined in their oeuvres. Through their creations, they

7 Title of eBook Chapter ______________________________________________________________ have constantly raised a crucial question that inevitably refers to our attitude towards time and the contemporary view of fashion, marked by a vivid tension between transitoriness and persistence.21 The particular ethic driving the work of such designers is clearly motivated by the refusal to be pervaded by the idea that fashion has to change and reinvent itself continuously. Yamamotos, Kawakubos, Margielas designs seem in fact to neglect any temporary and yet constricting tendency or direction. In replicating clothes form the past, for instance, they perform these reproductions, showing at the same time that there is no objective standpoint, outside history, from which ideas, old concepts, as well as their manifestations, can be dismantled, repeated, or reinterpreted. The constant dialogue with the past is precisely what allows Yamamoto, Kawakubo, Margiela, among the others, to point to new landscapes. A semiotic blur, as the theorist Iain Chambers points out,22 has for long characterized and still characterizes fashion, in which continuous mutations take place in such a way that can hardly be interpreted or fixed in the collective consciousness. The spiral of consumerism is indeed encouraged and enhanced by these fast and endless substitutions of imagery. The work of deconstructivist designers, on the contrary, is motivated by the awareness that what is present always sends back and refers to what is not hic et nunc, and hence that the process of creation does not happen in an empty blank dimension. Deconstructivist designers might be mainly known for their radical interpretation of fashion, but a thorough knowledge of fashion history is what precisely forms the base of their creativity. As Alison Gill remarks in particular about Margiela, the Maisons oeuvre is both a critique of fashions impossibility, against its own rhetoric, to be innovative, while at the same time showing its dependence on the history of fashion. These words best summarize a significant feature that is definitely common to all designers practicing deconstruction.23 In not being disciplined by any particular constraint except that of experimentation and recollection, deconstruction fashion addresses a provocation to consumer culture, in which the process of production is dramatically separated from the one of consumption. In relation to such a denounce, the theorist Herbert Blau has even dared to suggest that, if there is a politics of fashion, leaning left or right, the practice of deconstruction, as it was in the early nineties, might have been considered the last anti-aesthetic gesture of the socialists style.24 When they first came to prominence, designers practicing deconstruction were indeed revolting against the glamour that permeated the previous decade of fashion, in favour of what Blau calls an anaplasia of dress.25While individuating a manifest political intention in their works might be a too strong claim, their critical impetus towards fashion and culture cannot be underestimated. Far from being an evasion, or a product of pure fantasy, deconstruction fashion takes on a critical nuance. However, it 8 Name and Surname of Author(s) ______________________________________________________________ does not simply aim at replacing the old fashion parameters it tries to dismantle with new ones. Emblematic, in this respect, is the case of Margielas reconstructions stemming from raw materials. The deconstruction and reconstruction of clothing has been a leitmotif of Maison Martin Margiela's repertoire for years. Such a peculiarity finds its most significant expression in the Artisanal collection, for which existing clothes or humble materials, such as plastic, or paper, are re-worked in order to create new garments and accessories. The collection can be interpreted as the Maisons answer to the haute couture of the classic fashion system. The

unique items of the Artisanal Line are in fact fabricated with the same labourintensive manufacture as in haute couture. The term luxury, however, undergoes here a semantic shift: it does not mean the employment of some precious materials, but rather indicates the amount of hours worked for the production of each piece. By declaring such precise amount of hours, Margielas Artisanal collection unmasks human labour as the real source of the value that a certain garment holds. Recycling, nevertheless, is not the ultimate scope of Margielas fashion, which has been even compared, not appropriately, to Italian arte povera, or considered as a forerunner of ecofashion. 26 Borrowing, altering, manipulating becomes for Margiela a cultural and critical practice that deconstructs couture techniques and gives life to new formations by reassembling old clothing and raw materials. Caroline Evans draws a parallel between Margielas practice of fashion and the activity of bricoleurs in the newly industrialized landscape of early nineteenth century:27 Margielas transformations of abject materials in the world of high fashion mark him out as a kind of golden dustman or ragpicker, recalling Baudelaires analogy between the Parisian ragpicker and the poet in his poem Le Vin de Chiffoniers (The Ragpickers Wine). Like Baudelaires nineteenth-century poet-ragpicker who, although marglinal to the industrial processrecovered cultural refuse for exchange value, Margiela scavenged and revitalised moribund material and turned rubbish back into the commodity form. Margielas practice of recollecting and reconstructing, rather than being an explicit critique to the consumer culture and the fashion system, is an index of the consciousness that any critical fashion is always anchored in a specific moment of capitalistic production, consumption and technological change. It performs a critical reflection on fashion, unmasking its crystallized myths and commercial roots. The uncanny re-creations that finally emerge are characterized by a respectful attitude, and by the consciousness that individuality and contingency cannot be replicated, or better, that any 9 Title of eBook Chapter ______________________________________________________________ replication would bear a significant difference. By declaring the precise amount of hours required for the production of each piece, Margiela seems to overcome, even if temporarily, the alienation that for Karl Marx characterizes the relationship between the consumer and the product. According to the philosopher, the consumer is alienated from the product when the amount of time required to create it is no longer visible.28 Through the declaration of the labour intensive production, Maison Martin Margiela reconciles then the consumer with the process of production. It doing so, it remarks its debt towards the tradition and history of fashion, while at the same time it deconstructs the mechanisms of fascination and rediscusses our assumptions regarding fashion. As the philosophical deconstruction inaugurated by Derrida is an activity of reading which remains closely tied to the texts it interrogates, deconstruction fashion is not a simple and strategic reversal of categories. At the origin of such a practice there is always the consciousness that it can never constitute an independently and self-enclosed system of operative concepts. Just as there is no language, or no critical discourse, so vigilant or self-aware that it can effectively escape the condition placed upon its own prehistory and ruling metaphysics, there is no creation, or re-creation, allegedly pure or innocent. Any creation, as well as any critique, is always a situated practice; hence, deconstruction fashion itself is always already in-deconstruction. As Jacques Derrida has incessantly warned, deconstruction is not an operation that supervenes afterwards, from the outside. In an interview with

directors Kirby Dick and Amy Ziering, he says: you find it already in the thing itself. It is not a tool to be applied. It is always already at work in the thing we deconstruct.29 Through the deconstructing practice, and the exposure of the means that lead to the formation of certain idealized parameters, some designers have masterfully managed to problematize and re-think a series of opposing pairs (i.e. original-derived, subject-object, nature-culture, absence-presence, inside-outside), whose stronghold has for long been un-attacked. Through their questioning designs, they suggest, time and again, that everything can be re-interpreted and re-constructed differently. This uninterrupted movement from the finitude of the materiality to the infinite interpretation is what allows deconstructivist designers to understand the voice of historical tradition, in a dialogue that extends to the present, and demands the response of a project that is both individual and shared. Deconstruction fashion dwells thus in a place that is neither inside nor outside the fashion scenario, but stands always already on the edge or, in Derridean words, au bord . 10 Name and Surname of Author(s) ______________________________________________________________

N ote s

11 1 Before Derrida, Nietzsche has denounced the rigid and deathly regularity of the metaphysical heritage, which he compares to a Roman columbarium, On Truth and Lie in an Extra-Moral Sense, ed.by W.Kaufmann. Viking Penguin Inc, New York, 1976. On the connections between Derridas work and that of Nietzsche, as well as that of Freud and Heidegger, see Gayatri Chakravorty Spivaks preface to J.Derrida, Of Grammatology, translated by G.C.Spivak, John Hopskins University Press, Baltimore, MD and London, 1976. 2 Martin Heidegger, Being and Time, trans. John Macquarrie and Edward Robinson, Harper & Row, New York, 1962. 3 Deconstruction. II, ed.by A. Papadakis, Architecture Design, London, 1999, p.11. 4 Deconstruction. II, ed.by A. Papadakis, Architecture Design, London, 1999, p.7. 5 N.Sarup, Post-Structuralism and Post-Modernism, Harvester and Wheatsheaf, Hertfordshire, 1988, p.36. 6 Deconstruction. II, ed. by A. Papadakis, Architecture Design, London, 1999, p.8. 7 Deyan Sudjic reckons that a significant role in the impression that Kawakubo made in the western scenario of the early 1980s was the perceived exoticism of Japanese designers. He recalls: their arrival in Paris challenged the dominance of French designers, while at the same time underscoring the importance of Paris to the fashion system, D.Sudjic, Rei Kawakubo and Comme des Garons, Fourth Estate and Wordsearch, A Blueprint Monograph, London, 1990, p.84. 8 F.Baudot, Yohji Yamamoto, Thames and Hudson, London, 1997, p.10. 9 Coming Apart, by Amy M.Spindler, The New York Times, July 25th, 1993. 10 According to Mary McLeod, the term deconstructionist entered the vocabulary of fashion shortly after the Museum of Modern Arts Deconstructivist Architecture show in 1988, M.McLeod, Undressing Architecture: Fashion, Gender and Modernity in Architecture: in Fashion, edited by D.Fausch, P.Singley, R.El-Khoury, Z.Efrat, Preinceton Architectural , Press, New York, 1994, p.92. 11 Herbert Blau recalls that the rip, the tear, the wound that we associate with modernist wound was a factor in the sartorial mutilations of Commes des Garons some years before, when the notion of rending fabrics was still (or again) a radical gesture in the case of Rei Kawabukos designs, not only radical, but stylishly perverse. Kawabuko has since done clothes that are in a sense reconstructed, sewn to the body in panels by dauntless innumerable darts. In the tradition of the avantgarde, the conceptual operations behind the effects were sometimes overshadowed by the scandal of the effects. This was certainly a liability of la mode destroy, when Margiela designed jackets with the sleeves ripped off or converted ball gowns into jackets or cut up leather coats to make them into dresses [] This look had less of the gestural thickness of abstract expressionism than, with attenuated overlays of washed out found material, Rauschenbergs reworking of it as pictorial bricolage, Nothing in Itself, Indiana University Press, Bloomington and Indianapolis, 1999, p.177. 12 Coming Apart, by Amy M.Spindler, The New York Times, July 25th, 1993. 13 Ibidem. 14 E.Wilson, Adorned in Dreams, I.B.Tauris & Co. Ltd, London, 1985, p.250. 15 Deyan Sudjic, Rei Kawakubo and Comme des Garons, Fourth Estate and Wordsearch, A Blueprint Monograph, London, 1990, p.54. 16 F.Baudot, p.8. 17 Concerning the collaboration between Rei Kawakubo and artist Cindy Sherman, see H.Loreck, De/constructing Fashion/

Fashions of Deconstruction: Cindy Shermans Fashion Photographs, Fashion Theory: The Journal of Dress, Body & Culture, vol.6, i.3, pp.255-276. 18 A.ONeill, Imagining Fashion. Helmut Lang & Maison Martin Margiela, in Radical Fashion, ed.by C.Wilcox, V&A Publications, London, 2001, p.45. 19 B.Vinken, Fashion Zeitgeist, Berg, Oxford-New York, 2005, p.150. In grasping the peculiarity of Margielas oeuvre, the author reamrks: that the body is not a natural given but rather a construct is what Maison Martin Margielas fashion offers to our gaze through ever-new variations, B.Vinken, The New Nude, in Maison Martin Margiela 20 The Exhibition, ModeMuseum Provincie Antwerpen, Antwerp, 2008, p.112 20 C.Evans, Fashion at the Edge, Yale University Press, New Haven and London 2003, p.250. 21 Moreover, in complete contrast with the cult status enjoyed by fashion designers during the 1980s and the 1990s, Kawakubo, Margiela, Yamamoto, van Noten etc. use to draw attention on their work and to present the label as a result of a collective work, rather than an extension of the designers individuality. The choice of not appearing in public, as in Margielas case, or of rarely giving interviews immediately refers to the commitment to the collective working, in which the individuality of the author is completely immersed. 22 Concerning this aspect of fashion he argues: today we have reached such a level of cultural commodification that the duplicity of the sign, that is, that the product might actually mean something, can be done away with, I.Chambers, Maps for the Metropolis: a Possible Guide to the Present, in Cultural Studies, vol.1, no.1, January 1987, p.2. 23 In Wim Wenders short film Notebook on Cities and Clothes (1989), Yohji Yamamoto talks about the necessarily fugitive nature of images and goods in our days, which are dominated by the modality of consuming. In taking inspiration from the old days, that is, from images of factory workers belonging to another time, Yamamoto aims at drawing time. He says: I know myself in the present that is dragging the past. This is all I understand. 24 For a critique of Margielas work, as an exclusively aesthetic experience, see A.Ross (ed.), No Sweat: Fashion, Free Trade and the Rights of Garment Workers, Verso, New York and London, 1997. 25 Anaplasia is a medical term that means a reversion of differentiations in cells and is charachteristical of malign neoplasm (tumors). H.Blau, Nothing in Itself, p.175. 26 See Stephen OShea, Recycling: An all-New Fabrication of Style, Elle, 7, 1991. 27 C.Evans, Fashion at the Edge: Spectacle, Modernity and Deathliness, pp.249-250. , 28 K.Marx, Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, translated by B.Fowkes, Penguin Books, London, 1979, vol.1, Chaper I, 4 The Fetishism of the Commodity and Its Secret, pp.163-177. 29 Derrida The Movie, documentary by K.Dick and A.Ziering (2002).

B iblio gra phy

Baudot, F.,

You might also like

- FD 101 - Introduction To Fashion: Prepared By: Lean Marinor V. MoquiteDocument21 pagesFD 101 - Introduction To Fashion: Prepared By: Lean Marinor V. MoquiteLean Marinor MoquiteNo ratings yet

- French Costume Drama of the 1950s: Fashioning Politics in FilmFrom EverandFrench Costume Drama of the 1950s: Fashioning Politics in FilmNo ratings yet

- Calefato (2004) - The Clothed BodyDocument175 pagesCalefato (2004) - The Clothed BodyGeorgiana Bedivan100% (1)

- With Tongue in Chic: The Autobiography of Ernestine Carter, Fashion Journalist and Associate Editor of The Sunday TimesFrom EverandWith Tongue in Chic: The Autobiography of Ernestine Carter, Fashion Journalist and Associate Editor of The Sunday TimesNo ratings yet

- Sociology of Fashion - Order and ChangeDocument25 pagesSociology of Fashion - Order and ChangeAndreea Georgiana MocanuNo ratings yet

- Techno FashionDocument5 pagesTechno FashionMaria BurevskiNo ratings yet

- Construction of Gender Through Fashion and DressingDocument5 pagesConstruction of Gender Through Fashion and DressingAnia DeikunNo ratings yet

- The Impact and Significance of Fashion Trends On Culture and The Influence of Fashion On Our Everyday Lives.Document3 pagesThe Impact and Significance of Fashion Trends On Culture and The Influence of Fashion On Our Everyday Lives.Maricris EstebanNo ratings yet

- Fashion SocietyDocument37 pagesFashion SocietySitiFauziahMaharaniNo ratings yet

- Mike Kelley, 1999, Cross Gender-Cross GenreDocument9 pagesMike Kelley, 1999, Cross Gender-Cross GenreArnaud JammetNo ratings yet

- Art Deco in Modern FashionDocument4 pagesArt Deco in Modern FashionPrachi SinghNo ratings yet

- Paul PoiretDocument37 pagesPaul PoiretVicky Raj100% (1)

- Avant-Garde Fashion - A Case Study of Martin MargielaDocument13 pagesAvant-Garde Fashion - A Case Study of Martin MargielaNacho VaqueroNo ratings yet

- Fashion Forward 1 Ever 109132011Document445 pagesFashion Forward 1 Ever 109132011MichaelNo ratings yet

- Research Approaches To The Study of Dress and FashionDocument18 pagesResearch Approaches To The Study of Dress and FashionShishi MingNo ratings yet

- Dress and IdentityDocument9 pagesDress and IdentityMiguelHuertaNo ratings yet

- The Fashion: Bruno Pinheiro 8ºG Nº4Document6 pagesThe Fashion: Bruno Pinheiro 8ºG Nº4Bruno PinheiroNo ratings yet

- L. Skov, M. Riegels Melchior, 'Research Approaches To The Study of Dress and Fashion'Document18 pagesL. Skov, M. Riegels Melchior, 'Research Approaches To The Study of Dress and Fashion'Santiago de Arma100% (2)

- The Development of Fashion Industry in The UsDocument5 pagesThe Development of Fashion Industry in The UsAnna Maria UngureanuNo ratings yet

- Fashion and The Fleshy Body Dress As Embodied PracticeDocument26 pagesFashion and The Fleshy Body Dress As Embodied PracticeMadalina ManolacheNo ratings yet

- A Book Guide For Fashion Design Area Students by Aurora Fiorentini Edited by Marcella Mazzetti For Polimoda LibraryDocument22 pagesA Book Guide For Fashion Design Area Students by Aurora Fiorentini Edited by Marcella Mazzetti For Polimoda LibrarySofie SunnyNo ratings yet

- History of Fashion DesignDocument11 pagesHistory of Fashion DesignJEZA MARI ALEJONo ratings yet

- Fashion Designer SchiaparelliDocument3 pagesFashion Designer SchiaparelliFunguh Solified100% (1)

- Architecture FashionDocument11 pagesArchitecture FashionMaria BurevskiNo ratings yet

- Fashion Design For A Projected Future: Annette AmesDocument16 pagesFashion Design For A Projected Future: Annette AmesBugna werdaNo ratings yet

- Theories of Fashion Costume and Fashion HistoryDocument10 pagesTheories of Fashion Costume and Fashion HistoryAdelina Amza100% (1)

- Moeran, Brian. (2006) - More Than Just A Fashion Magazine.Document22 pagesMoeran, Brian. (2006) - More Than Just A Fashion Magazine.Carolina GutierrezNo ratings yet

- Le Mark Fashion Design Textile Design UG Brochure 2020 21 1Document35 pagesLe Mark Fashion Design Textile Design UG Brochure 2020 21 1Karan MorbiaNo ratings yet

- Fashion, Sociology Of: December 2015Document9 pagesFashion, Sociology Of: December 2015Allecssu ZoOzieNo ratings yet

- Versace CatalogueDocument193 pagesVersace CatalogueMarcelo MarinoNo ratings yet

- Bloomsbury Fashion CentralDocument5 pagesBloomsbury Fashion CentralLaura B.No ratings yet

- 90s Fashion Trends - EditedDocument3 pages90s Fashion Trends - EditedNorthlandedge ConsultantsNo ratings yet

- Paul PoiretDocument9 pagesPaul Poiretapi-534201968No ratings yet

- (Materializing Culture) Tereza Kuldova - Luxury Indian Fashion - A Social Critique-Bloomsbury Academic (2016)Document228 pages(Materializing Culture) Tereza Kuldova - Luxury Indian Fashion - A Social Critique-Bloomsbury Academic (2016)অদেবপ্রিয় মজুমদারNo ratings yet

- Deconstruction and FashionDocument8 pagesDeconstruction and FashionnitakuriNo ratings yet

- Hussien ChalayanDocument8 pagesHussien ChalayanPrasoon ParasharNo ratings yet

- The Berg Companion: To FashionDocument12 pagesThe Berg Companion: To FashionAndreea Maria Miclăuș100% (1)

- Francis Upritchard BookletDocument4 pagesFrancis Upritchard Bookletapi-280302545No ratings yet

- Cultural Economy of Fashion BuyingDocument21 pagesCultural Economy of Fashion BuyingUrsu DanielaNo ratings yet

- Fashion A Reader Table of Contents 133846Document12 pagesFashion A Reader Table of Contents 133846Marko Todorov50% (2)

- Zonemoda Journal Vol.5 Fashion ConvergenceDocument4 pagesZonemoda Journal Vol.5 Fashion ConvergenceZonemodaNo ratings yet

- NVIT BLANCHE: The Rituals of CraftsmanshipDocument6 pagesNVIT BLANCHE: The Rituals of CraftsmanshipAamaalYasminAbdul-MalikNo ratings yet

- Costume Designers Costumers Fashion DesignersDocument2 pagesCostume Designers Costumers Fashion Designersamalia guerreroNo ratings yet

- ERRICKSON, April (1999) - A Detailed Journey Into The Punk Subculture PDFDocument33 pagesERRICKSON, April (1999) - A Detailed Journey Into The Punk Subculture PDFlukdisxitNo ratings yet

- Coursework History of FashionDocument10 pagesCoursework History of Fashionapi-583724756No ratings yet

- Evans Margiela 1998Document12 pagesEvans Margiela 1998Cami Buah100% (2)

- Fashion History ReportDocument10 pagesFashion History Reportapi-489872825100% (1)

- Museum Quality The Rise of The Fashion ExhibitionDocument26 pagesMuseum Quality The Rise of The Fashion ExhibitionMadalina Manolache0% (1)

- Fashion HistoryDocument13 pagesFashion HistoryNickolas VasNo ratings yet

- FearOfFashion WDocument210 pagesFearOfFashion WElma McGougan100% (1)

- Architecture Fashion A Study of The Conn PDFDocument28 pagesArchitecture Fashion A Study of The Conn PDFkiranmayiyenduriNo ratings yet

- Fashion Meets Architecture BriefDocument12 pagesFashion Meets Architecture Briefindrajit konerNo ratings yet

- JYO - Fashion Etymology & Terminology - FinalDocument57 pagesJYO - Fashion Etymology & Terminology - FinalSushant BarnwalNo ratings yet

- Film and FashionDocument7 pagesFilm and FashionAmy BranchNo ratings yet

- Alternative Femininities Body Age and Identity Dress Body CultureDocument224 pagesAlternative Femininities Body Age and Identity Dress Body CultureLindaNo ratings yet

- 10 1 1 460 3329 PDFDocument53 pages10 1 1 460 3329 PDFRoxana Andreea PopaNo ratings yet

- Democratisation of FashionDocument12 pagesDemocratisation of FashionchehalNo ratings yet

- The Current and Future Prospect of Streetwear A Study Based On Various Textile WearDocument9 pagesThe Current and Future Prospect of Streetwear A Study Based On Various Textile Wear078Saurabh RajputNo ratings yet

- Fashion Openness Applying Open Source Philosophy To The Paradigm of Fashion Optika - Mustonen - Natalia - 2013Document180 pagesFashion Openness Applying Open Source Philosophy To The Paradigm of Fashion Optika - Mustonen - Natalia - 2013Edith LázárNo ratings yet

- Fetishism in FashionDocument7 pagesFetishism in FashionEdith Lázár100% (1)

- Ricoeur What Is A TextDocument12 pagesRicoeur What Is A TextJacky TaiNo ratings yet

- Darning Mark Jumper, Wearing Love and Sorrow, by Karen de PerthuisDocument19 pagesDarning Mark Jumper, Wearing Love and Sorrow, by Karen de PerthuisEdith LázárNo ratings yet

- Light Writing Desire and Other Fantasies: Telling Tales Catalogue Essay by Anne MarshDocument10 pagesLight Writing Desire and Other Fantasies: Telling Tales Catalogue Essay by Anne MarshEdith LázárNo ratings yet

- PSA Guide To Publishing 2015 - 0Document60 pagesPSA Guide To Publishing 2015 - 0Fayyaz AliNo ratings yet

- WACK! Gallery GuideDocument9 pagesWACK! Gallery GuideEdith LázárNo ratings yet

- PSA Guide To Publishing 2015 - 0Document60 pagesPSA Guide To Publishing 2015 - 0Fayyaz AliNo ratings yet

- Embodied Resistance NodrmDocument289 pagesEmbodied Resistance NodrmAna Maria Ortiz100% (1)

- The Sense of BeinThe Sense of Being (-) With Jean-Luc NancyDocument9 pagesThe Sense of BeinThe Sense of Being (-) With Jean-Luc NancyEdith LázárNo ratings yet

- Local Knowledge and New MediaDocument224 pagesLocal Knowledge and New MediaEdith LázárNo ratings yet

- Bennet Andy Youth Culture Pop MusicDocument17 pagesBennet Andy Youth Culture Pop MusicEdith LázárNo ratings yet

- Art Criticism Bound To FailDocument3 pagesArt Criticism Bound To FailEdith LázárNo ratings yet

- Transfiguration of The Common Place/shortDocument11 pagesTransfiguration of The Common Place/shortEdith LázárNo ratings yet

- EmbodimentDocument14 pagesEmbodimentEdith Lázár100% (1)

- The Culture of ImmanenceDocument4 pagesThe Culture of ImmanenceNita MocanuNo ratings yet

- Art ReasearchDocument7 pagesArt ReasearchEdith LázárNo ratings yet

- Benveniste Problems in General LinguisticsDocument267 pagesBenveniste Problems in General Linguisticssinanferda100% (7)

- 1 4 Modernity and The Spaces of Femininity: Modern Life: Paris in The Art Manet and His Followers, by T. J. Clark, 3Document23 pages1 4 Modernity and The Spaces of Femininity: Modern Life: Paris in The Art Manet and His Followers, by T. J. Clark, 3Laura Adams DavidsonNo ratings yet

- Power System Protection (Vol 3 - Application) PDFDocument479 pagesPower System Protection (Vol 3 - Application) PDFAdetunji TaiwoNo ratings yet

- EP07 Measuring Coefficient of Viscosity of Castor OilDocument2 pagesEP07 Measuring Coefficient of Viscosity of Castor OilKw ChanNo ratings yet

- Advanced Oil Gas Accounting International Petroleum Accounting International Petroleum Operations MSC Postgraduate Diploma Intensive Full TimeDocument70 pagesAdvanced Oil Gas Accounting International Petroleum Accounting International Petroleum Operations MSC Postgraduate Diploma Intensive Full TimeMoheieldeen SamehNo ratings yet

- Glossary of Blasting TermsDocument13 pagesGlossary of Blasting TermsNitesh JainNo ratings yet

- Consumer Protection ActDocument34 pagesConsumer Protection ActshikhroxNo ratings yet

- Chapter1 Intro To Basic FinanceDocument28 pagesChapter1 Intro To Basic FinanceRazel GopezNo ratings yet

- Exclusive GA MCQs For IBPS Clerk MainDocument136 pagesExclusive GA MCQs For IBPS Clerk MainAnkit MauryaNo ratings yet

- UG ENGLISH Honours PDFDocument59 pagesUG ENGLISH Honours PDFMR.Shantanu SharmaNo ratings yet

- 5045.CHUYÊN ĐỀDocument8 pages5045.CHUYÊN ĐỀThanh HuyềnNo ratings yet

- Ford Focus MK2 Headlight Switch Wiring DiagramDocument1 pageFord Focus MK2 Headlight Switch Wiring DiagramAdam TNo ratings yet

- LP Week 8Document4 pagesLP Week 8WIBER ChapterLampungNo ratings yet

- Music Production EngineeringDocument1 pageMusic Production EngineeringSteffano RebolledoNo ratings yet

- UAP Grading Policy Numeric Grade Letter Grade Grade PointDocument2 pagesUAP Grading Policy Numeric Grade Letter Grade Grade Pointshahnewaz.eeeNo ratings yet

- HR Practices in Public Sector Organisations: (A Study On APDDCF LTD.)Document28 pagesHR Practices in Public Sector Organisations: (A Study On APDDCF LTD.)praffulNo ratings yet

- Optical Transport Network SwitchingDocument16 pagesOptical Transport Network SwitchingNdambuki DicksonNo ratings yet

- Ticket: Fare DetailDocument1 pageTicket: Fare DetailSajal NahaNo ratings yet

- Equilibrium of A Rigid BodyDocument30 pagesEquilibrium of A Rigid BodyChristine Torrepenida RasimoNo ratings yet

- Brain Injury Patients Have A Place To Be Themselves: WHY WHYDocument24 pagesBrain Injury Patients Have A Place To Be Themselves: WHY WHYDonna S. SeayNo ratings yet

- Acceptable Use Policy 08 19 13 Tia HadleyDocument2 pagesAcceptable Use Policy 08 19 13 Tia Hadleyapi-238178689No ratings yet

- Assignment - 1 AcousticsDocument14 pagesAssignment - 1 AcousticsSyeda SumayyaNo ratings yet

- PDF BrochureDocument50 pagesPDF BrochureAnees RanaNo ratings yet

- Makalah Bahasa Inggris TranslateDocument14 pagesMakalah Bahasa Inggris TranslatevikaseptideyaniNo ratings yet

- The Future of FinanceDocument30 pagesThe Future of FinanceRenuka SharmaNo ratings yet

- Req Equip Material Devlopment Power SectorDocument57 pagesReq Equip Material Devlopment Power Sectorayadav_196953No ratings yet

- MegaMacho Drums BT READ MEDocument14 pagesMegaMacho Drums BT READ MEMirkoSashaGoggoNo ratings yet

- Investment Analysis and Portfolio Management: Frank K. Reilly & Keith C. BrownDocument113 pagesInvestment Analysis and Portfolio Management: Frank K. Reilly & Keith C. BrownWhy you want to knowNo ratings yet

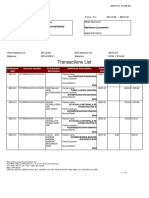

- Transactions List: Marilena Constantin RO75BRDE445SV93146784450 RON Marilena ConstantinDocument12 pagesTransactions List: Marilena Constantin RO75BRDE445SV93146784450 RON Marilena ConstantinConstantin MarilenaNo ratings yet

- EPMS System Guide For Subcontractor - V1 2Document13 pagesEPMS System Guide For Subcontractor - V1 2AdouaneNassim100% (2)

- Investigation Data FormDocument1 pageInvestigation Data Formnildin danaNo ratings yet

- Painters Rates PDFDocument86 pagesPainters Rates PDFmanthoexNo ratings yet

- A Lapidary of Sacred Stones: Their Magical and Medicinal Powers Based on the Earliest SourcesFrom EverandA Lapidary of Sacred Stones: Their Magical and Medicinal Powers Based on the Earliest SourcesRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (2)

- Crochet Cute Dolls with Mix-and-Match Outfits: 66 Adorable Amigurumi PatternsFrom EverandCrochet Cute Dolls with Mix-and-Match Outfits: 66 Adorable Amigurumi PatternsRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5)

- The 10 Habits of Happy Mothers: Reclaiming Our Passion, Purpose, and SanityFrom EverandThe 10 Habits of Happy Mothers: Reclaiming Our Passion, Purpose, and SanityRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (6)

- Wear It Well: Reclaim Your Closet and Rediscover the Joy of Getting DressedFrom EverandWear It Well: Reclaim Your Closet and Rediscover the Joy of Getting DressedRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Bulletproof Seduction: How to Be the Man That Women Really WantFrom EverandBulletproof Seduction: How to Be the Man That Women Really WantRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (169)

- The Kingdom of Prep: The Inside Story of the Rise and (Near) Fall of J.CrewFrom EverandThe Kingdom of Prep: The Inside Story of the Rise and (Near) Fall of J.CrewRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (26)

- Metric Pattern Cutting for Women's WearFrom EverandMetric Pattern Cutting for Women's WearRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (3)

- Modern Ladies' Tailoring: A basic guide to pattern draftingFrom EverandModern Ladies' Tailoring: A basic guide to pattern draftingRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (13)

- Pattern Drafting and Foundation and Flat Pattern Design - A Dressmaker's GuideFrom EverandPattern Drafting and Foundation and Flat Pattern Design - A Dressmaker's GuideRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (13)

- Skincare for Your Soul: Achieving Outer Beauty and Inner Peace with Korean SkincareFrom EverandSkincare for Your Soul: Achieving Outer Beauty and Inner Peace with Korean SkincareRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- 250 Japanese Knitting Stitches: The Original Pattern Bible by Hitomi ShidaFrom Everand250 Japanese Knitting Stitches: The Original Pattern Bible by Hitomi ShidaRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (7)

- The Basics of Corset Building: A Handbook for BeginnersFrom EverandThe Basics of Corset Building: A Handbook for BeginnersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (17)

- Vintage Knit Hats: 21 Patterns for Timeless FashionsFrom EverandVintage Knit Hats: 21 Patterns for Timeless FashionsRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (4)

- Wear It Well: Reclaim Your Closet and Rediscover the Joy of Getting DressedFrom EverandWear It Well: Reclaim Your Closet and Rediscover the Joy of Getting DressedRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Glossy: Ambition, Beauty, and the Inside Story of Emily Weiss's GlossierFrom EverandGlossy: Ambition, Beauty, and the Inside Story of Emily Weiss's GlossierRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Basic Black: 26 Edgy Essentials for the Modern WardrobeFrom EverandBasic Black: 26 Edgy Essentials for the Modern WardrobeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (10)

- Make Your Mind Up: My Guide to Finding Your Own Style, Life, and Motavation!From EverandMake Your Mind Up: My Guide to Finding Your Own Style, Life, and Motavation!Rating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (391)

- The Beginner's Guide to Kumihimo: Techniques, Patterns and Projects to Learn How to BraidFrom EverandThe Beginner's Guide to Kumihimo: Techniques, Patterns and Projects to Learn How to BraidRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (3)

- The Ultimate Book of Outfit Formulas: A Stylish Solution to What Should I Wear?From EverandThe Ultimate Book of Outfit Formulas: A Stylish Solution to What Should I Wear?Rating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (23)

- Freehand Fashion: Learn to sew the perfect wardrobe – no patterns required!From EverandFreehand Fashion: Learn to sew the perfect wardrobe – no patterns required!Rating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (3)

- DIY Updos, Knots, & Twists: Easy, Step-by-Step Styling Instructions for 35 Hairstyles—from Inverted Fishtails to Polished Ponytails!From EverandDIY Updos, Knots, & Twists: Easy, Step-by-Step Styling Instructions for 35 Hairstyles—from Inverted Fishtails to Polished Ponytails!Rating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (7)

- Fabric Manipulation: 150 Creative Sewing TechniquesFrom EverandFabric Manipulation: 150 Creative Sewing TechniquesRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (13)

- Creative Polymer Clay: Over 30 Techniques and Projects for Contemporary Wearable ArtFrom EverandCreative Polymer Clay: Over 30 Techniques and Projects for Contemporary Wearable ArtNo ratings yet

- Knitting In the Sun: 32 Projects for Warm WeatherFrom EverandKnitting In the Sun: 32 Projects for Warm WeatherRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (8)

- Skincare Bible: Dermatologist's Tips For Cosmeceutical Skincare: Beauty Bible SeriesFrom EverandSkincare Bible: Dermatologist's Tips For Cosmeceutical Skincare: Beauty Bible SeriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (14)

- Masterpieces of Women's Costume of the 18th and 19th CenturiesFrom EverandMasterpieces of Women's Costume of the 18th and 19th CenturiesRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (5)