Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Zen and The Actor

Uploaded by

EilonOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Zen and The Actor

Uploaded by

EilonCopyright:

Available Formats

Zen and the Actor David Feldshuh The Drama Review: TDR, Vol. 20, No.

1, Theatre and Therapy. (Mar., 1976), pp. 79-89.

Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0012-5962%28197603%2920%3A1%3C79%3AZATA%3E2.0.CO%3B2-%23 The Drama Review: TDR is currently published by The MIT Press.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/about/terms.html. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/journals/mitpress.html. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission.

The JSTOR Archive is a trusted digital repository providing for long-term preservation and access to leading academic journals and scholarly literature from around the world. The Archive is supported by libraries, scholarly societies, publishers, and foundations. It is an initiative of JSTOR, a not-for-profit organization with a mission to help the scholarly community take advantage of advances in technology. For more information regarding JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

http://www.jstor.org Fri Oct 26 15:21:15 2007

Zen and the Actor

By David Feldshuh

Zen has been called "the religion of n o religion." It is a branch of Buddhism, both having originated in a single event: the enlightenment of Guatama Siddhartha who, after meditating for six years, is said t o have awakened, as if from a dream, t o become The Enlightened One, the Buddha. It is significant that the seed of Zen Buddhism was neither a set of scriptures nor a messianic creed, but the dedication of a single man t o gain greater perception into his own nature and the nature of reality through meditation. The practice of meditation is at the heart of Zen, and the word "Zen," derived from the Chinese "Ch'uan," means "meditation." Predicated on practice rather than belief, without sacred scriptures, fixed canon, o r Divine being, Zen is "no religion." It is rather a type of training intended t o promote a special presence, a particular quality of consciousness with which t o meet the world. What is this form of consciousness that Zen brings t o its interface with the world? In the men's room of the London Academy of Music and Dramatic Art in 1966, directly in front of the toilet, there was scrawled this graffiti: "Live the moment." This precept for vital, magnetic acting has its Zen counterpart for Zen also urges that you live fully in the "eternal now." Whatever you are doing, Zen enjoins you t o d o it with the fullness of your being. If it were in an Eastern men's room, the graffiti might have read: "When peeling the potato don't think of the Buddha, just peel the potato." Professional quarterback John Brodie voiced a similar injunction:

The player can't be worrying about the past or the future or the crowd or some other extraneous event. He must be able to respond in the here and now; I believe we all have this naturally; maybe we lose it as we grow up. (Adam Smith, Psychology Today, October 1975)

80

DAVID FELDSHUH

Contemporary theorists have evolved numerous techniques t o enlarge the individual's capacity t o experience and participate in the now. These techniques, generally regarded as avenues toward expanding human potential, are united by a common premise: the individual is capable of more-more expression, more originality, more freedom. In his body training work, for example, Moshe Feldenkrais attempts t o foster a psychophysical state of maximum efficiency with minimum effort. He defined this "potent state" as:

. . . a special pattern of nervous activity, in conjunction with a muscular configuration and a corresponding pattern of vegetative impulses, in which the capacity and liberty of the frame to attempt and realize any act is at its greatest . . . (Kristin Linklater, T53.)

The Alexander Technique, Structural Integration, and bioenergetic therapy also attempt to promote functioning that is spontaneous, flexible, and efficient. Although each discipline has its own techniques, all attempt t o unravel resistances imbedded in the body structure. Zen approaches emancipation into full participation in the present moment through the avenue of the mind. (The word "mind" is used in a specific way. It refers t o the internal dialog of words and images that the individual carries on with himself.) Zen practice suggests that there is a mental "potent state," an optimum inner condition for creative functioning. This inner condition has various names but may be usefully labeled, t o use Shunryu Suzuki's phrase, "Zen Mind."

The practice.of Zen mind is beginner's mind. . . . What is beginner's mind? It is an empty mind and a ready mind. If your mind is empty, it is always ready for anything; it is open to everything. (Shunryu Suzuki, Zen Mind, Beginner's Mind.)

In Zen in the Art of Archery, Eugen Herrigel describes this quality of consciousness as "right presence of mind":

This state, in which nothing definite is thought, planned, striven for, desired or expected, which aims in no particular direction and yet knows itself capable alike of the possible and the impossible, so unswerving in its power-this state, which is at the bottom purposeless and egoless, was called by the master truly "spiritual." It is in fact charged with spiritual awareness and is therefore called "right presence o f mind." This means that the mind or spirit is present everywhere because it is nowhere attached to any particular place. And it can remain present because, even when relnted to this or that object, it does not cling to it by reflection and thus lose its original mobility. Like water filling a pond, which is always ready to flow o f f again, it can work its inexhaustive power because it is free, and be open to everything because it is empty. This state is essentially a primordial state . . .

The Japanese martial arts of karate and aikido ascribe t o this concept of mind. Karate means "empty hand." This refers not t o a hand empty of weapons, but t o the principle that, t o be successful in karate, one must approach the activity of the moment with an "empty hand," the symbol for a mind empty of thought. In aikido, the quality of Zen mind has been described in various colorful ways:

If your mind is open and everywhere receptive like the calm surface of a lake that reflects first the moon then a flying bird but holds no trace o f them when they have passed, but is ready to catch the lightest blowing o f the wind, so you will not only be able to quickly catch any movement your opponent might make, but will also be able accurately to reflect the tone o f any movement around you. (Koichi Tohei, Aikido in Daily Life.)

ZEN AND THE ACTOR

81

Zen training is dedicated t o promoting Zen mind. There are two main schools of Zen training, each with their own emphasis: The Rinzai school and the Soto school. The core of the Rinzai method is the "koan," which incorporates unanswerable riddles such as:

One day Unmon said to his disciples. 'If you don't see a man for three days, do not think he is the same man. How about you?' No one spoke, so he said, 'One thousand. '

The paradox for Western consciousness is that the koan cannot be answered with thought. On the contrary, rationalization is a hindrance t o finding the answer and only when all avenues of thought are exhausted, when mental computation and qualification are defeated, when the computer mind is "short circuited," will the answer be experienced in a moment of enlightenment, called "satori." The koan possesses "seeds of shock . . . t o break open the sealed door of ordinary consciousness" and must be answered with "no-thought," with an empty-mind. For the koan is an experience of intuition. (D.T. Suzuki in The World of Zen.) In the Rinzai school, "seated meditation," o r zazen, is used t o awaken the student's intuitive capacities by "stilling the babbling brook" of conscious awareness. The Soto school practices zazen as an end in itself. The influence of this school is very strong in the United States because its forenlost spokesman, Shunryu Suzuki, established the first Soto Zen monastery in this country at Tassajara, California, as well as the Zen Center in San Francisco, and Green Gulch Farm in Marin County, California. Suzuki thinks not at all about enlightenment. His focus is simply on doing zazen. He believes that Zen is zazen, and enlightenment is bringing zazen t o your everyday life. In the zendo (meditation hall) of the Zen Center in San Francisco, there are about sixty small rectangular black pads, t w o feet wide and three feet long, called zanikus. On each zaniku there is a small, round, tightly-packed sitting cushion, or zafu. These are the only accoutrements of zazen, aside from the bells and blocks of wood sounded t o signal the beginning and end of each forty-minute sitting period, some incense, a modest altar, and a small, smooth wooden stick about three feet long, used t o waken drifting minds by landing a sharp smack o n each shoulder, a smack that resounds about the empty hall with a frightening echo. T o sit zazen is t o sit cross-legged, o r in the lotus or half-lotus position, with your knees on the zaniku and the buttocks on the zafu. The hands are held in a position called the "cosmic mudra" and the weight of the body is distributed on three points: both knees and the buttocks. Kosho Uchiyama, head of a Soto Zen temple in Kyoto, gives this description of the proper zazen posture:

Sit up and straighten your back as if you were pushing your buttocks into the zafu. Keep your neck straight and pull in your chin. Without leaving an air pocket inside, close your mouth and put your tongue firmly against the upper palate. Project your head as if it were going t o pierce the ceiling. Relax your shoulders. Put your right hand on top o f your left foot and put your left hand in the palm of the right. Your thumbs should meet above your hands. . . . Your ears should be in line with your shoulders and your nose in line with your navel. Keep your eyes open as usual, look at the wall, and drop your line o f vision slightly. .. . Once you've taken the immovable posture breathe quietly through the nose. me important thing is to let long breaths be longand short breaths be short.

The zazen posture is compared by Uchiyama with the posture of Rodin's Thinker. The posture of the Thinker is cramped, clutched, tight, a posture that promotes a chasing after thoughts and a weaving of fantasies about events in the past o r the future. This posture hinders the capacity of the mind t o clear. The upright zazen posture, o n the other hand, allows blood t o flow from the brain.

82

DAVID FELDSHUH

If you fall asleep when seated in the zazen posture, you are no longer doing zazen. If you are thinking thoughts, weaving fantasies, finding interesting patterns on the wall or judging how well you have managed to hold your zazen posture, you are no longer doing zazen. Zazen is a state of full awakening-pure perception without self-observation. This is not to say that during zazen thoughts do not occur. They occur but you learn to let them drift away, like leaves floating downstream on a river.

What is 'letting go of thought?'. . . we think of 'something'. . . Thinking o f 'something' means grasping that something with thought. But during zazen we open wide the hand of thought which is trying to grasp something, and don't grasp anything at all. This is 'letting go of thoughts.' Dogen Zenji . . . called this 'the thought of no thought. ' (Kosho Uchiyama, Approach to Zen.)

The aikido understanding of how to allow the mind to still is similar to the Zen perspective:

Pow some water into a tub and stir it up. Now try as hard as you can to calm the water with your hands; you will succeed only in agitating it further. Let it stand undisturbed a while, and it will calm down by itself. The human brain works the same way. When you think, you set up brain waves. Dying to calm them down by thinking is only a waste. (Tohei.)

In training the performing artist, it is vital to distinguish between rational and intuitive knowledge. Rational knowledge is knowledge about things. It involves deducing or inferring conclusions from accumulated information. Intuitive knowledge, on the other hand, is not knowledge "about." It is direct and experiential, knowledge by acquaintance not by description. In experiencing intuitive understanding, the artist is not a spectator but a participant. This kind of knowledge cannot be acquired through the intellect. Zen training, in contrast to a university education, focuses on intuition rather than intellect. For Descartes, thinking was proof of existence-cogito ergo sum.Zen meditation is clearly premised on an opposing proposition-"I think, therefore, I am not." Admittedly, intuition is an elusive quantity, a shadowy force that seems t o evaporate under the light of scrutiny. For this reason many teachers have refused to encounter the challenge of training intuition in any direct way. "Don't talk about it, just do it," is a repeated and often useful response to young drama students who insist on "understanding" the acting process. However, this prejudice against "talking," if simply a negation, is only partially useful. It does not suggest what the "it" is that cannot be talked about. Nor does this injunction offer a way to intensify the young actor's experience and acquaintance with the "it" that can only be touched by going beyond the boundaries of "talking about." To "just do it" leads as often to ignorance as intuition. Abraham Maslow, a prominent psychologist interested in creativity, states that "it"

. . . can come only if a person's depths are available t o him, only i f he is not afraid o f his primary thought processes.

. . . the analysts agree that inspiration or great (primary) creativeness comes partly out o f the unconscious. . . . (Toward a Psychology of Being.)

Zen also views creativity as flowing from a region beyond the conscious mind. Intuition, like a stream, is waiting to bubble forth through the artist. Although this flow cannot be forced, the individual can learn how to get out of the way, to eliminate blocks and more readily allow the creative unconscious to manifest itself. This perspective is captured in the Zen story of the cat who is a master of catching mice. When the other cats

ZEN AND THE ACTOR

83

ask her how she does it, she calmly purrs. It is not that the cat refuses t o answer, but rather that she cannot answer for her artistry does not proceed from the conscious mind. The cor~sciousmind is crucial only because it is a lilniting factor in the creative process. It n a y be pictured as a tunnel through which creative impulses flow, o r a screen upon which these impulses play. When the conscious mind is filled, this tunnel becomes blocked and the screen becomes cloudy. Zen mind is the optimum mental condition for creative functioning. For only when the conscious mind is emptied of distracting thought will the organism be permeable to the flow of creative impulse. The source of creative action is called the "Zen Unconscious." The Unconscious is not a limited, personal sphere, but has universal dimension. When the artist quiets his mind and succeeds in turning "himself into a puppet at the hands of the Unconscious" creativity becomes inevitable. (Langdon Wainer, in The World o f Zen.) Because this creative life force is brimming beneath the surface of the conscious mind, the artist must learn, in Heidegger's words, to "attune himself t o that which wants t o reveal itself and permit the process t o happen through him." When creative action does occur it is not because the artist has achieved something new. Rather, he has learned t o tap a universal and natural creative force. It is for this reason that the Zen archer, refusing personal credit, admonishes the pupil: "It is not I who must be given credit for the shot. 'It' shot and 'it' made the hit." (Eugen Herrigel, Zen in the Art of Archery.) T. S. Eliot speaks of the shadow lying between thought and action. The Zen mind attempts to eliminate the shadow of self-consciousness allowing the artist, as DaVinci observed, to go u p the tunnel backwards, t o create without "double-mindedness." For "double-rnindedness" results in continuous "wobbling": action followed by correction. The niind will not let go t o allow full participation, but rather continuously "shortcircuits" creative involvement by observing and judging. Creative behavior, even within strict form, must attempt t o be instantaneous and unpremeditated, without interference of mind or thought, like the sound arising when you clap your hands--there is n o separation between the clap and the sound. This is the meaning of the Zen injunction that inveighs against the dithering between opposites and falling into self-conscious, selfcorrecting action: "In walking walk, in sitting sit; above all, don't wobble." In Zen there is a word for the division between mind and activity. It is suki, which means "a space between two objects," o r "a slit or split or crack in one solid object." (Alan Watts, The Way of Zen.) All separations between thinking and acting are forms of suki and result in a stopping that breaks up the flow of creativity and responsiveness.

Fbr a man rings like a cracked bell when he thinks and acts with a split mind-one part standing aside to interfere with the other, to control, to condemn, or to admire . . . instead o f flowing . . . from one object to another, the mind halts and reflects on what it is going to do or what it has already done . . . this interferes with the jluiditv of mentation and the lightning rapidity of action. (D. T . Suzuki, Zen and Japanese Culture.)

Suki also results in self-conscious emotional expression. For feeling

. . . blocks itself as a form o f action, when it gets caught in this same tendency to observe or feel itself indefinitely-as when in the midst o f enjoying myself, I examine myself to see if I am getting the utmost out o f the occasion. Not content with tasting the food, I am also trying to taste my tongue. Not content with feeling happy, I want to feel myself feeling happy -so as to be sure not to miss anything. (Watts.)

On the level of physical movement, suki imposes an overlay of thought that may hinder expressive and spontaneous movement. 'To regain spontaneity, the Zen artist must

84

DAVID FELDSHUH

again create after long years of study from a region beyond conscious awareness, and, equally important, he must study t o forget study and himself. When the artist is no longer identified with the idea of himself, perfect identification may take place between the person and his behavior.

The knower no longer feels himself t o be independent of the known; the experiencer no longer feels himself to stand apart from the experience . . . watching I one's breath . . . b y a slight change of viewpoint it is as easy t o feel that ' breathe' as that 'it breathes me.'

(Watts.)

This capacity for total identification, so important to the performing artist, is the ultimate result of zazen. Although acting theory can only be tested through practical application and the observation of results, there is some scientific data suggesting that the practice of zazen may be valuable to the actor. In a study using psychological tests, an attempt was made to measure the effect of practicing zazen for one month (five times a week for thirty minutes each session) on the empathetic ability of counselors. These individuals were being taught to become more sensitive t o their own internal psychic processes. This training was also an attempt to help counselors to stop projecting by experiencing the difference between images or ideas in their own minds and stimuli coming from the client. In Zen terms, the individual was receiving training in getting below the idea of the self in order to contact reality more fully. Two of the conclusions reached through this study were:

1-The group that practiced zazen over a four-week period improved in their empathetic ability. 2-Zen meditation holds far more potential for personal growth and scientific investigation than wns previously supposed. (Terry V . Lech in Biofeedback and Self-Control.)

A number of studies reveal that new and original images may appear to individuals when they are on the borderline between being asleep and being awake. In this state, as in zazen, the conscious mind has quieted, allowing deeper images to surface. A second resemblance between this state and zazen has been revealed through the use of biofeedback apparatus. Electroencephalogram readings have shown that these near-sleep images are often associated with the production of alpha brain waves. Alpha brain waves, though usually evident only when the eyes are closed, are produced during zazen (even by inexperienced meditators) when the eyes are open and when the individual is fully respon'sive (not in a drowsy, near-sleep state). There is a Zen saying that the man who is fully engaged in zazen can hear ashes fall in the altar urn. This emphasizes that zazen is not a trance-like slumber. Experiments done by Dr. Tomio Hirai confirm that I ) zazen brings about a change in brain waves; 2) the effects produced by zazen linger even after zazen has ended; 3 ) even those with a little experience can produce these effects; and 4) zazen and sleep are different. The last conclusion was reached by using instruments to measure brain waves and changes of electrical potential of the skin (galvanic skin response). The non-meditating control subject became habituated to the sound of a bell so that his GSR diminished, finally disappearing. Subjects practicing zazen produced completely different results. Dr. Hirai arrived at the following conclusions:

I-As the GSR tests showed, the brain in this condition responds quickly t o external stimuli but immediately returns to the tranquil state. 2-Unlike people who are asleep, people in zazen meditation are receptive to

ZEN AND THE ACTOR

exterior stimuli. Indeed they are more sensitive to such stimuli than waking people under ordinary circumstances. 3-Repetition of exterior stimuli does not produce a state of familinrity in which response is deadened. On the contrary, the fresh sensitivity of the brain waves o f a person in zazen remains undimmed for long periods. 4-Examinations of the brain waves o f meditating people show that the human mind is completely capable of being calm and static while remaining tensely aware o f and receptive to its surroundings. When the mind is emittirig calm Alpha waves and encounters an exterior stimulus it reacts in an active way. In terms o f brain waves, this phenomenon consists of Alpha blocking-temporary cessation of Alpha wave emission-and o f the emission o f active Beta waves. Furthermore, in the zazen state of meditation, Alpha blocking always occurs at repeated encounters with external stimuli; that is, the brain never becomes so accustomed t o a given stimulus that it ceases to respond to it. In the zazen meditation state, the mind always manifests both the active and the static condition. This is the scientific explanation for the Zen condition that is described as the oneness of the active and the static. (Tomio Hirai, Zen Meditation Therapy.)

The results discussed above have clear relevance t o the performing artist and the actor in particular. The counselor failing t o distinguish between his own imaginings and the cues given by the client parallels the actor who goes onstage with a fixed, preconceived Gestalt, a particular mental construct that prevents him from being fully responsive t o new stimuli in the environment (a new line reading, a changed position of a prop, etc.). When Eugen Herrigel speaks of "calculation that is miscalculation," h e recognizes that a mind filled with thought can block both incoming stimuli and outgoing impulse. This is why the Zen student is encouraged t o awaken from his self-centered consciousness so that "there is n o self. There is only reality." Zazen, like near-sleep, allows the individual t o become aware of new creative resources, resources that are usually submerged below conscious awareness. Finally, Dr. Hirai's observations about the unity of calm and action, a marriage basic t o the Zen martial arts, suggests an intriguing hypothesis: Is the actor, when most creative, producing wavelengths associated with semi-conscious, creative states (Alpha) in spite of the fact that his behavior is obviously active? In fact, is brilliant acting a type of zazen-full presence, full awakening integrated with a calm, still core? Though these questions are unanswered and perhaps incapable of proof, they are useful, since zazen is an available and practical technique. Further, the assumption that Zen Mind can be useful t o the actor, that Zen Mind is Actor's Mind (the optimum inner condition for creativity in the acting process) may fill some gaps in current approaches t o actor training, and shed light o n the process of acting as well. Many teachers can testify t o moments when an acting student suddenly came t o life and displayed an unexpected richness of talent. Where did this sudden ability come from? What was happening this time that had failed t o happen all those other times? The previous discussion suggests that n o activity is in itself creative or non-creative. I t is n o t the kind of activity that the individual engages in but the quality of psychophysical training brought t o any activity that is responsible for catapulting it from the mundane t o the inspirational. This approach also implies that everyone has talent (the capacity t o experience more fully), though some stand in the way of their natural creativity more effectively than others. It is a goal of actor training t o make the individual aware of his own enormous capacities, of how he prevents their full realization, and of techniques that can assist him in achieving a richer creative presence. Actor training of this kind would require a two-pronged approach: I ) t o build the outer craft necessary for performance; 2) t o train an inner readiness that allows the actor t o totally integrate this craft and bring it t o the service of the momentary creative impulse.

86

DAVIT) FELDSHUA

One problem with a good deal of actor training is that there is vely little training in how t o forget training. There is little training in learning how t o let go of rehearsal, how t o forget that it is opening night or that critics are in the audience, how t o let go of the calculating self and t o give fully t o "the Self that knows without knowing." But this is the final step in any actor's process: t o allow the present t o work o n him in the most expressive way possible, t o be-here-now for what is supposed t o happen in the script. The actor must be trained in many techniques, but without Actor's Mind these techniques cannot be fully actualized. Actor's Mind is the inner condition necessary t o integrate any technique into the creative act, an act that goes beyond the boundaries of conscious control or analytic intelligence requiring the capacity t o surrender t o the moment and live fully in it. This quality of consciousness resembles an animal state in its reliance on the wisdom of the total organism. In this state thinking becomes an instantaneous, non-deliberative reaction. 'The mind is not confined, the attention is not limited t o any single aspect. Self-consciousness disappears because there is n o split in awareness. There is n o turning back o r wobbling because the mind is fluid. Even though the actor has rehearsed a movement o r line again and again, each creation is new, coming alive and dying a t every moment in front of the audience. In developing the capacity for Actor's Mind the individual is increasing his ability t o open t o an expanded state of consciousness. The following description of a Zen master captures the quality of existence that flows from the condition of Actor's Mind, and suggests that brilliant acting and brilliant living are mirror images. The Zen Master is

. . . a person who has actualized that perfect freedom which is the potentiality for all human beings. He exists freely in the fullness of his whole being. The flow of his consciousness is not fixed repetitive patterns of our usual self-centered consciousness, but rather arises spo~~taneously naturally front the actual circurnand stances o f the present.

.. . His

whole being testifies to what it means to live in the reality of the (Suzuki.) present. . . .

In various fields, individuals can testify t o this expanded state of consciousness when fear of failure suddenly vanishes t o be replaced by an infusion of creative ease and resiliency. Charlotte Doyle, a psychologist, has given this part of the creative episode a name, the period of total concentration:

It is the period, for the writer, when the characters take over, when the melodies flow without forcing, when the painting seems to paint itself. The artist is totally absorbed in the work. All the awkwardness that comes f i o n ~ watching yourself at work, from the fear that what you are doing is no good, from careful critical selection is no longer a part of the flow of thought and action. The artist's head, his hands, his lips are totally directed by the forces that have been generated by the sense of direction and the ideas-in-flesh as he is working with them. All intellectual and emotional resources, all skills and experiences become part of the artist's reach and movement toward the eventual goal. This total concentration is a particular kind o f consciousness. . . . (In Essays from Sarah Lawrence Faculty, Sept. 1975)

In Zen, this kind of experience is an opportunity for enlightenment or satori.

The Chinese character for "satori" is composed o f the character for "rnind"arzd the character for "myself." When "myself" and "mind" are completely united, there is satori. . .. (Ruth Fuller Sasaki in The World of Zen.)

ZEN AND THE ACTOR

87

D. 'P. Suzuki views satori as an intuitive understanding that gives a new perspective, a turning around of perception so that there occurs an "unfolding of a new world hitherto unperceived in the confusion of a dualistic mind."

. . . at the moment of satori man "thinks with his heart and loves with his brain. "

These two functions are no longer distinct, and, in fact, they have never been so. Satori is intelligence of the heart.

In terms of sensation, satori has been described as:

. . . a serene pulsation which can be heightened into the feeling otherwise experienced only in rare dreams, o f extraordinary lightness, and the rapturous certainty of being able t o summon up energies in any direction. . . . (Robert Linssen, Living Zen.)

From the Zen perspective, creativity may result in artistic o r partial satori. This experience is more limited than the satori of the Zen man which "covers the totality of his being." (Herrigel.) It is, nonetheless, the supreme moment for the artist. This kind of experience, though rare and indelible, is not uncommon. Quarterback Brodie relates:

Sometimes in the heat o f a game a player's perception improves dramatically. A t times I experience a kind of clarity that I've never seen described in any football story; sometimes this seems to slow way down, as if everyone were moving in slow motion. It seems as if I have all the time in the world to watch the receivers run their patterns, and yet I know the defensive line is coming at me just as fast as ever, and yet the whole thing seems like a movie or a dance in slow motion. It's (Smith.) beautiful.

Many actors can recount situations in which they have "given up" only t o find that their performances have more originality and life than ever before. This resembles the experience of Jean Belmonte, the matador, and suggests that satori state may arise when the artist is at the end of his resources and has exhausted all efforts t o "think" his way out. He then explodes and lets go of ideas and memory, relying on something beyond his small ego-self.

I was overcome with despair. Where had I got the idea that I was a bullfighter? You've been fooling yourself, I thought. Because you had some luck in a couple of novilladas without picadors, you can do anything. . . . They say that my passes with the cape and m y work with the muleta that afternoon were a revelation o f the art o f bullfighting. I don't know and I'm not competent t o judge. I simply fought as I believe one ought t o fight, without a thought outside m y own faith (D. T. Suzuki understands this word to mean Zen Unconscious) in what I was doing. With the last bull I succeeded for the first time in my life in delivering myself body and soul to the pure joy of fighting. . . .

(D. T . Suzuki.)

The instantaneity integral t o the satori experience presents the performing artist with a difficult challenge. He must be open t o spontaneity, and yet this spontaneity must be filtered through form. This seems t o necessitate a split (suki) in the actor between the judging consciousness and involvement in the activity at hand, which throws the actor onto the horns of Diderot's paradox: a warm heart but a cool, observing head. Zen provides a way out of this paradox by emphasizing that there is a kind of knowing that does not require conscious control. Through practice and repetition the individual can learn t o "know without knowing," without deliberation and without conscious memory. The actor is neither controlled nor out of control. For his creativity emanates from a

88

DAVID FELDSHUH

unified organism and from a region previous t o any kind of internal separation. Such a performance is a living denial of the long-standing, though fallacious, dichotomy between techniques and emotion. Zen points t o this conclusion in the following poem:

Control or not controlled?

The same dice shows two faces.

Not controlled or controlled,

Both are a grievous error.

(Paul Reps, Zen Flesh, Zen Bones.) The actor who has learned t o let go and surrender t o "spontaneity without caprice" is like a good bonfire. The Zen precept is: "When you d o something, you should burn yourself completely, like a good bonfire, leaving n o trace of yourself." In the creative performance, the actor burns himself completely within the form dictated by script and production. To burn himself completely, the actor must be in the condition of Actor's Mind. For without Actor's Mind

.. . before we act we think, and this thinking leaves some trace. Our activity is shadowed by some preconceived idea. . . .

(Shunryu Suzuki.)

In Zen, the metaphor of the child exemplifies the capacity of non-thinking that is necessary for spontaneity and immediacy:

You must hold the drawn bowstring . . . like a little child holds the proffered finger. It grips so firmly that one marvels at the strength of the tiny fist. And when it lets the finger go, there is not the slightest jerk. Do you know why? Bemuse a child doesn't think: I will now let go of the finger in order to grasp this other thing. Completely unselfconsciously, without purpose, it turns from one to the other, and we would say that it was playing with things, were it not equally true that the things are playing with the child. (Herrigel.)

The child also illustrates a second prerequisite of brilliant acting, which is the capacity t o let things happen through the organism rather than the organism forcing things t o happen. Any activity is organic insofar as the whole organism participates in it. It lacks this organic quality t o the degree that the organism stands outside of itself and is a spectator t o the act of the moment. T o let things happen through him, the actor must learn t o let go of his fear of losing himself. The archery master observes:

. . . you do not let go o f yourself. . . . You do not wait for fulfillment, but brace yourself for failure. So long as it is so, you have no choice but to call forth something that ought to happen independently o f you, and so long as you call it forth your hand will not open in the right way-like the hand o f a child; it does not burst open like the skin o f a ripe fruit. . . . (Herrigel.)

Full presence, identity with other actors and audience, and the experience of acting from a region beyond conscious control are all marks of performance at its highest level of effectiveness. These qualities are illustrated in the practice of both aikido and karate. They are, however, most vitally demonstrated by a sister art, ancient Japanese swordsmanship, or kendo. Kendo strongly resembles both karate and aikido, but with an important difference-the undeniable possibility of death. Burdened with this consequence, the swordsman, more than any other artist, is thrust into living fully in the present. Faced with the possibility of death, the swordsman is freed from the considerations of life. He need not pretend t o live in the moment for he knows that the moment is all h e may have t o live. Paradoxically, the awareness of death enables full presence in life.

ZEN AND THE ACTOR

89

When swordsmanship attains the level of satori, the artist experiences n o separation between himself and the sword. As the following quote suggests, swordsman and opponent are also felt t o merge.

. . . I as swordsman see no opponent confronting me and threatening to strike me. I seem to transform myself into the opponent, and every movement he makes as well as every thought he conceives are felt as i f they were all my own and I intuitively, or rather unconsciously know when and how to strike him. All seems to be so natural. (Takano Shigeyoshi in The World of Zen.)

In the satori state, the swordsman appears t o be responding t o a force greater than and beyond himself.

[The sword] moves not of itself. In a similar manner, the swordsman's sword, including the man behind it, moves not o f itself; that is, he is free from all ego-centered motives. It is his unconscious, not his analytical intelligence, that controls his behavior. Beoause o f this, the swordsman feels that the sword is controlled by some agent unknown to him and yet not related to him. All the technique he has consciously and with a great deal of pains learned now operates as i f directly from the fountainhead of the Unconscious. . . . (D. T. Suzuki.)

The swordsman's lesson is straightforward: the performing artist must be capable of risking all of himself. He must be willing and able t o dissolve himself into the process of acting; t o surrender; t o "die" each moment and t o be born fully each moment. The swordsman knows he must risk all. The actor must convince himself. It is obvious that Zen is not done only in the zendo. It is not just a form of meditation but a way of life, a state of mind. Any human activity, t o the degree that the individual gives himself fully over t o it, is a form of zazen. The acting process itself is a form of zazen, of continually bringing one's self back t o the present and learning t o be-here-now. But in zazen this problem, of living-here-now, is isolated. Therefore, zazen offers the opportunity t o experience an essential aspect of the acting process with pristine intensity. "When you understand one thing through and through," Shunryu Suzuki said, "you understand everything." Zazen teaches that meaning is derived from the quality of presence given t o any effort, and that in doing something fully you come t o an understanding of yourself. This brings t o all the activities of everyday life a new sense of value. As, in Stanislavsky's thinking there are "no small parts," in Zen:

There are no actions which we should consider as 'ordinary'in contrast to others which we regard as 'exceptional' or extraordinary. Zen asks us to bring to bear the intensity of an extraordinary attention in the midst of so-called 'ordinary' circumstances. (Linssen.)

The practice of zazen has obvious implications for the person as well as the actor.

In our daily lives, we will not be carried awny by the comings and goings of life-like images. We will be able to 'wake up' to our own lives and begin completely afresh fiom the reality o f life. . . . We can see that thoughts, desires and delusions are the scenery of life. (Christmas Humphreys in The World of Zen.)

Whatever keeps us from "being-here-now" can be seen as delusion, like cinema images that fade when shades are opened and bright sun is allowed t o enter. The ultimate step in the process of fully living and fully acting, in theatre and therapy, is the same-waking u p t o the present.

You might also like

- Guidelines Paul AntonioDocument4 pagesGuidelines Paul Antonioadamkor100% (2)

- Sanford MeisnerDocument4 pagesSanford MeisnerYudhi FaisalNo ratings yet

- Up-Ending The Tea Table: Race and Culture in Mary Zimmerman's The Jungle BookDocument23 pagesUp-Ending The Tea Table: Race and Culture in Mary Zimmerman's The Jungle BookDavid Isaacson100% (2)

- About Fool For Love Rereading ShepardDocument18 pagesAbout Fool For Love Rereading ShepardErna SmailovicNo ratings yet

- Barba 2002 - Essence of Theater PDFDocument20 pagesBarba 2002 - Essence of Theater PDFbodoque76No ratings yet

- Respect For Acting - Uta Hagen PDFDocument2 pagesRespect For Acting - Uta Hagen PDFMarlo RubalcabaNo ratings yet

- Sarah Kane - 4:48 PsychosisDocument6 pagesSarah Kane - 4:48 PsychosisSophie CapobiancoNo ratings yet

- The Theatre of Pina Bausch. Hoghe PDFDocument13 pagesThe Theatre of Pina Bausch. Hoghe PDFSofía RuedaNo ratings yet

- Analyzing Acting PerformanceDocument3 pagesAnalyzing Acting Performancechrimil100% (2)

- Michael Chekhovs Golden HoopDocument6 pagesMichael Chekhovs Golden HoopRobertoZuccoNo ratings yet

- ACTING General HandoutDocument4 pagesACTING General HandoutNagarajuNoolaNo ratings yet

- ARCHITECTURE IN CAMBODIADocument8 pagesARCHITECTURE IN CAMBODIAJohnBenedictRazNo ratings yet

- Meditation Handbook by Christopher CalderDocument15 pagesMeditation Handbook by Christopher CalderrafaeloooooooNo ratings yet

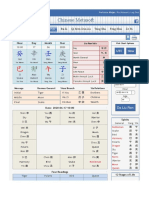

- Chinese Metasoft: Home Products Ba Zi Qi Men Dun Jia Tong Shu Feng Shui Ze RiDocument2 pagesChinese Metasoft: Home Products Ba Zi Qi Men Dun Jia Tong Shu Feng Shui Ze RiShiju P Sheepee0% (1)

- Civilization in China, Japan and KoreaDocument21 pagesCivilization in China, Japan and KoreamagilNo ratings yet

- Business Success MantraDocument2 pagesBusiness Success MantraJaya SwamyNo ratings yet

- The Tao of Acting: What Makes an ActorDocument78 pagesThe Tao of Acting: What Makes an ActorNick ArcherNo ratings yet

- Acting Presentation On StellaDocument7 pagesActing Presentation On Stellaapi-463306740No ratings yet

- Books and Resources for Acting Training and Career DevelopmentDocument2 pagesBooks and Resources for Acting Training and Career DevelopmentamarghitoaieiNo ratings yet

- Using The Stanislavski Method To Create A PerformanceDocument32 pagesUsing The Stanislavski Method To Create A PerformanceAlexSantosNo ratings yet

- John Gillett (2012) Experiencing or Pretending-Are We Getting To The Core of Stanislavski's Approach, Stanislavski Studies, 1-1, 87-120Document35 pagesJohn Gillett (2012) Experiencing or Pretending-Are We Getting To The Core of Stanislavski's Approach, Stanislavski Studies, 1-1, 87-120Gustavo Dias VallejoNo ratings yet

- Acting Techniques: Body Language Facial Expression Campy Marshall NeilanDocument3 pagesActing Techniques: Body Language Facial Expression Campy Marshall NeilanMarathi CalligraphyNo ratings yet

- Working With ActorsDocument21 pagesWorking With ActorsJoel BrandãoNo ratings yet

- Final When The Rain Stops FallingDocument14 pagesFinal When The Rain Stops FallingYonatan GrossmanNo ratings yet

- Stanislavski Scene AnalysisDocument6 pagesStanislavski Scene AnalysisSofia RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Stage Composition Workshop Examines Theatrical PrinciplesDocument6 pagesStage Composition Workshop Examines Theatrical PrinciplesJuciara NascimentoNo ratings yet

- Stella Adler On IbsenDocument5 pagesStella Adler On IbsenKyleNo ratings yet

- Beyond Stnslvski PDFDocument146 pagesBeyond Stnslvski PDFIrina Naum100% (2)

- Acting 'The Six Steps of Character Analysis'Document1 pageActing 'The Six Steps of Character Analysis'Lauren SchwecNo ratings yet

- VGL Theatre & WorkshopsDocument2 pagesVGL Theatre & WorkshopsDanny DawsonNo ratings yet

- Stanislavakian Acting As PhenomenologyDocument21 pagesStanislavakian Acting As Phenomenologybenshenhar768250% (2)

- Peter Brook's Critique of "Deadly TheatreDocument2 pagesPeter Brook's Critique of "Deadly TheatreGautam Sarkar100% (1)

- A Concise Introduction To Actor TrainingDocument18 pagesA Concise Introduction To Actor Trainingalioliver9No ratings yet

- Fitz Maurice VoiceDocument31 pagesFitz Maurice VoiceTyler SmithNo ratings yet

- 09 - The Stella Adler Actors Approach To The Zoo Story PDFDocument32 pages09 - The Stella Adler Actors Approach To The Zoo Story PDFasslii_83No ratings yet

- Directing With The Michael Chekhov Technique by Mark MondayDocument4 pagesDirecting With The Michael Chekhov Technique by Mark MondaynervousystemNo ratings yet

- The Persisting VisionDocument12 pagesThe Persisting VisionKiawxoxitl Belinda CornejoNo ratings yet

- ACTING PHOBIAS AND CHARACTER CREATIONDocument26 pagesACTING PHOBIAS AND CHARACTER CREATIONmxtimsNo ratings yet

- Coach actors with emotion exercisesDocument8 pagesCoach actors with emotion exercisesAntonio VettrainoNo ratings yet

- Method Acting - WikipediDocument6 pagesMethod Acting - WikipedichrisdelegNo ratings yet

- Japanese Theatre Transcultural: German and Italian IntertwiningsDocument1 pageJapanese Theatre Transcultural: German and Italian IntertwiningsDiego PellecchiaNo ratings yet

- Meyerhold's Key Theoretical PrinciplesDocument27 pagesMeyerhold's Key Theoretical Principlesbenwarrington11100% (1)

- Michael ChekhovDocument2 pagesMichael Chekhovapi-541653384No ratings yet

- An Actor Prepares NotesDocument1 pageAn Actor Prepares NotesEsther WalkerNo ratings yet

- Translating The Inner Event To An Outer ExpressionDocument10 pagesTranslating The Inner Event To An Outer ExpressionerikarojNo ratings yet

- Stanislavski NotesDocument9 pagesStanislavski Notesapi-250740140No ratings yet

- Actors On ActingDocument14 pagesActors On ActingBriareusNo ratings yet

- Approaches To Acting.1Document8 pagesApproaches To Acting.1joshuabonelloNo ratings yet

- A Higher Calling Phillip Seymor HoffmanaDocument14 pagesA Higher Calling Phillip Seymor Hoffmanaalchymia_ilNo ratings yet

- Exercises Inspired by Sanford Meisner's Repetition ExerciseDocument121 pagesExercises Inspired by Sanford Meisner's Repetition ExerciseCharlie CurilanNo ratings yet

- Acting Coaches.08.10.10Document6 pagesActing Coaches.08.10.10bandito427No ratings yet

- Acting NotesDocument3 pagesActing Notesapi-676894540% (1)

- Actor Centered and Truth in Performance - Mike AlfredsDocument1 pageActor Centered and Truth in Performance - Mike Alfredsapi-364338283No ratings yet

- Russian Actor Training Method Active Analysis Explored in UK Drama SchoolsDocument16 pagesRussian Actor Training Method Active Analysis Explored in UK Drama SchoolsMaca Losada Pérez100% (1)

- The Odd Couple 1x01 - PilotDocument50 pagesThe Odd Couple 1x01 - PilotØrjan LilandNo ratings yet

- Exploring Shakespeare: A Director's Notes from the Rehearsal RoomFrom EverandExploring Shakespeare: A Director's Notes from the Rehearsal RoomNo ratings yet

- On Chekhov - Working With The Intangible - Radiation, A Twenty-First Century Interpretation Amanda BrennanDocument14 pagesOn Chekhov - Working With The Intangible - Radiation, A Twenty-First Century Interpretation Amanda BrennanJon BradshawNo ratings yet

- Michael ChekhovDocument3 pagesMichael ChekhovMariana SilvaNo ratings yet

- Art As VehicleDocument3 pagesArt As VehicleJaime SorianoNo ratings yet

- Qi Gong FiguresDocument2 pagesQi Gong Figuresapi-3821211100% (1)

- Eugen Herrigel PDFDocument2 pagesEugen Herrigel PDFMarshaNo ratings yet

- Trust in Mind(信心铭·中英对照) PDFDocument15 pagesTrust in Mind(信心铭·中英对照) PDFAnonymous NQfypL100% (1)

- Diamond Ray of Quan Yin for adjustment (a gift and execution of giftDocument4 pagesDiamond Ray of Quan Yin for adjustment (a gift and execution of giftladyksa100% (2)

- Walter Y. Evan-Wentz - The Tibetan Doctrine of The Dream StateDocument10 pagesWalter Y. Evan-Wentz - The Tibetan Doctrine of The Dream Statefjscariot100% (1)

- Jin SarasawatiDocument303 pagesJin SarasawatiDJICR100% (6)

- The Ten Precepts of TaoismDocument4 pagesThe Ten Precepts of TaoismCharles Reginald K. HwangNo ratings yet

- Healthy NormalDocument3 pagesHealthy NormalAnders Kassem KaltoftNo ratings yet

- Sleep and Various Schools of Indian PhilosophyDocument24 pagesSleep and Various Schools of Indian PhilosophyBrad YantzerNo ratings yet

- Thailand's rich history and cultureDocument82 pagesThailand's rich history and cultureAbdulManafNo ratings yet

- Fu Zhong Wen Taiji.2.Document9 pagesFu Zhong Wen Taiji.2.César EscalanteNo ratings yet

- Zhong Huis Laozi Commentary and The Debate On Capacity and Nature in Thirdcentury ChinaDocument59 pagesZhong Huis Laozi Commentary and The Debate On Capacity and Nature in Thirdcentury ChinaAbe BillNo ratings yet

- Tao-Te-Ching by Lao Tze - An Interpolation of Several Popular English Trns by Peter A MerelDocument51 pagesTao-Te-Ching by Lao Tze - An Interpolation of Several Popular English Trns by Peter A Merelmorefaya2006100% (1)

- Self-Assessment Tool For Mureeds The Beginning of An OutlineDocument4 pagesSelf-Assessment Tool For Mureeds The Beginning of An OutlineRodrigo BittencourtNo ratings yet

- BuddhaNet's Buddhist Crossword PuzzlesDocument22 pagesBuddhaNet's Buddhist Crossword Puzzlessimion100% (2)

- Beyond Form - Http-Dahamvila-Blogspot-ComDocument21 pagesBeyond Form - Http-Dahamvila-Blogspot-ComDaham Vila BlogspotNo ratings yet

- The Great Messages - Translated To EnglishDocument136 pagesThe Great Messages - Translated To Englishmaximomore100% (1)

- The Blue Cliff RecordDocument32 pagesThe Blue Cliff RecordJeff KlassenNo ratings yet

- Only Knowing: Commentary on Vasubandhu's Trimsika-karikaDocument11 pagesOnly Knowing: Commentary on Vasubandhu's Trimsika-karikarishi patel100% (2)

- Tara GreenTara Ringu Tulku Rinpoche Practice of Green TaraDocument73 pagesTara GreenTara Ringu Tulku Rinpoche Practice of Green TaraJarosław Śunjata100% (3)

- Left-Hand Path and Right-Hand PathDocument6 pagesLeft-Hand Path and Right-Hand Pathfstazić67% (3)

- Intro Medicine WheelDocument2 pagesIntro Medicine WheelryandakotaNo ratings yet

- Taoism & ConfucianismDocument7 pagesTaoism & ConfucianismMel TrincaNo ratings yet

- The Charvaka Way of Life, Charvaka Philosophy, Indian PhilosophyDocument4 pagesThe Charvaka Way of Life, Charvaka Philosophy, Indian PhilosophyJulia Blackwolf100% (2)