Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Anzmac 10 Final 00206

Uploaded by

Jagamohan OjhaOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Anzmac 10 Final 00206

Uploaded by

Jagamohan OjhaCopyright:

Available Formats

Page - 1 - of 9

ANZMAC

Retail Mixes in Diverse Retail Formats for Involvement Needs and Customer Loyalty Nic S Terblanche, University of Stellenbosch, nst@sun.ac.za

Abstract To keep customers loyal has been and is continuing to pose a challenge to retail managers. Consumers display differing levels of involvement in their buying decisions that vary with the nature and characteristics of the product/service under consideration when they shop, the type of retailer (retail format) and the retail mix on offer. Particular components of the retail mix may address the customers involvement with the store positively and as such become important drivers of loyalty. The primary purpose of this study was to empirically assess the validity of this contention. This study found that customer loyalty is driven by different variables in a retail mix that address involvement concerns, depending on the type of retail store. Keywords: Retail mix, retail formats, involvement, loyalty

Page - 2 - of 9

ANZMAC

Retail Mixes in Diverse Retail Formats for Involvement Needs and Customer Loyalty Abstract To keep customers loyal has been and is continuing to pose a challenge to retail managers. Consumers display differing levels of involvement in their buying decisions that vary with the nature and characteristics of the product/service under consideration when they shop, the type of retailer (retail format) and the retail mix on offer. Particular components of the retail mix may address the customers involvement with the store positively and as such become important drivers of loyalty. The primary purpose of this study was to empirically assess the validity of this contention. This study found that customer loyalty is driven by different variables in a retail mix that address involvement concerns, depending on the type of retail store. Introduction The role of involvement in marketing has been studied from various perspectives such as, for instance, customer involvement, product involvement, cognitive involvement and affective involvement. Goldsmith & Emmert (1991) described product involvement as the feelings of interest and enthusiasm that consumers hold for different product categories. The focus of this study is on the retailing mix the retailer must provide in-store to enhance the shopping efficiency of their customers if they wish to enhance loyalty amongst their customers. In particular the differences in in-store retail mixes that customers require in the shopping environment, mainly in respect of low versus high involvement products, are investigated. Retailers therefore have to understand the in-store retail mix their customers require to enable them to make an informed decision and to enhance customer loyalty. Problem Investigated Customer involvement varies for different types of retailers, depending on the type of merchandise and/or services offered by the retailer. Certain products, because of their use as status symbols or importance for the physical or psychological wellbeing of a customer, cause customers to spend more time in a shop, require more information, require the assistance of sales staff for advice and want an opportunity to complain should the need arise. The extent to which a retail store provides facilities, staff, information, etcetera to address involvement expectations of their customers, should also influence the loyalty of the customer towards the retailer. Whether this contention is valid is the problem investigated in this study. Objective The nature of a product or service determines the extent to which a consumer will become involved when shopping. The characteristics of a product or service thus trigger customer involvement. Retailers respond to these different needs by offering a particular retail mix. In other words, a low involvement product will be retailed with a different retail mix than a high involvement product. Some retail mix attributes are therefore more important to a customer in assisting him or her to address the demands of their level of involvement. The primary objective of this study is to ascertain which in-store retail mix attributes must be in place to satisfy customer involvement demands in four diverse retailing environments namely a superstore, a supermarket, a clothing store and a wellness, beauty and lifestyle (WBL) retailer. A secondary objective is to determine which in-store retail mix attributes (the independent

Page - 3 - of 9

ANZMAC

variables) in the four retailing environments impact on customer loyalty (the dependent variable). Customer Involvement According to Beharrell and Denison (1995) the concept of involvement initially developed in the field of social psychology where involvement was viewed as the association between ego and an object. Later on the antecedents or sources that influenced different types of involvement namely, enduring, situational and response gained prominence. As far as situational factors are concerned, Mittal (1989) and Zaichkowsky (1985) argued that the role of these factors in involvement should be regarded as qualifiers to involvement at both the product class and purchase level. Zaichkowsky (1985) found that involvement is a situational characteristic that influence the extent and kind of information a customer utilises in a buying situation. Park, Iyer, and Smith (1989) and Chattopadhyay and Alba (1988) have highlighted how in-store stimuli can influence decisions in a shopping situation with varying degrees of involvement. The raison d'tre why customers engage at different levels of involvement, is related to the risk they perceive in any given shopping situation. A large volume of research has explored the relationship between product involvement and consumer risk perception (Richins, Bloch and McQuarrie, 1992; Venkatraman, 1989). Generally speaking, one can assume that the higher the risk perceived by a customer is, the more in-store retail mix dimensions the customer will employ to guide him or her in the shopping process. If a retailer succeeds in providing all the inputs necessary for a customer to reduce the risk involved in a purchasing decision, it is also likely to lead to behavioural and attitudinal loyalty. Product/Service Involvement as a Customer-defined Construct Traylor (1981: 51) argues that it is wrong to present products as either high or low involvement products, seeing that strictly speaking, no product is inherently ego involving or uninvolving and the characteristics of high or low involvement are based on the perceptions of consumers. Researchers usually refer to high/low involvement products when the extent of the endeavour demonstrated is of a little magnitude (low involvement) or substantial magnitude (high involvement). Martin (1998: 9) suggested that particular products command more involvement than other products because the characteristics of the products/brands themselves or their usage contexts may systematically act to arouse consumers involvement. Quester, Karunaratna and Lim (2001) found a relationship between product involvement and brand loyalty and that the dimensions of involvement varied in accordance with the product category under consideration. Customer Loyalty Customer loyalty has been defined in various ways, ranging from a probability of repurchase to a proportion of purchase (Sivadas and Baker-Prewitt, 2000). At a general level, customer loyalty is a positive propensity toward a store or brand (East et al., 2000). Jacoby and Chestnut (1978) identified over fifty operational definitions of loyalty and found that the idea that is central to many of these definitions is that the extent of loyalty is determined by the proportion of expenditure devoted to a specific brand or store (East et al., 1995). Dick and Basu (1994) and Mellens, Dekimpe and Steenkamp (1996) have reviewed different measures of propensity towards brands and stores. The general conclusion from these and other research is that loyalty is both a cognitive construct (attitude) and a shopping behavior. Loyal

Page - 4 - of 9

ANZMAC

customers can be regarded as a competitive asset to a business organisation (Dekimpe et al., 1997). The Retail Mix Based on both the literature review and empirical testing (Terblanche and Boshoff, 2006) the following dimensions of the in-store retail mix influence involvement at retailer level: Personal Interaction; Merchandise Value; Complaint Handling; Internal Store Environment and Merchandise Variety and Assortment. These 5 constructs emerged after 8 components of store image were factor analysed and capture the essential dimensions to address customerbased store involvement and attend to the psychological, physical and situational dimensions of involvement discussed earlier. The constructs are also suitable to measure customer involvement for different types of retailers and served as independent variables in predicting store loyalty in this study. The Typical Behaviour and Retail Mix Expectations of Shoppers in Respect of Different Retail Store Types This section reviews the typical behaviour and expectations of shoppers in four distinct types of retail stores, namely a supermarket, a superstore, a clothing store and a store selling wellness, beauty and lifestyle products. The intention is to highlight distinctive behaviour and expectations that are unique to a particular group of shoppers and which determines each retail categorys distinctive retail mix requirements to meet their needs for a particular level of involvement. Supermarket shoppers The speed of shopping made possible by a gridiron layout in combination with price, usually combines to appeal to supermarket shoppers (Davies et al., 2001:40). Price, as an extrinsic cue, is essential to supermarket shoppers as they generally do not regard the time and effort required to evaluate intrinsic cues as meaningful (Sirohi et al, 1998:227). Based on the discussion above, we suggest the following proposition: P1 : In a supermarket environment consumer loyalty will be determined by merchandise value Superstore shoppers A superstore is very similar but bigger than a supermarket, and although its focus remains on food, it is more diversified than a supermarket. Superstores do, however, offer even less services to customers than supermarkets even the shelving is of a spartan nature. Given the dominance of price in the superstore consumers buying decision and the similarities between superstores and supermarkets, allow us to suggest the following proposition: P2 : In a superstore environment consumer loyalty will be determined by merchandise value Clothing store shoppers Salespeople, especially their appearance and interaction with customers, are important for shoppers when they shop for clothes and their presence will determine customer will take advice from them and return for future purchases (De Klerk, Velleman and Malherbe, 1998:15-24). Torres, Summers and Belleau (2001:207) found that the key clothing store

Page - 5 - of 9

ANZMAC

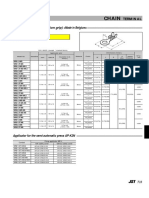

attributes (in order of importance) are the price, quality and selection of merchandise; brands carried in the store and friendly personnel. Mahoney and Sternquist (1989:101-111) and Thorpe and Avery (1983:35-41) earlier confirmed that sales staffs competence and knowledge are essential store attributes for clothing shoppers. Based on the discussion above, we suggest the following proposition: P3 : In a clothing store environment customer loyalty will be determined by personal interaction, the in-store environment and merchandise value Wellness, beauty and lifestyle product shoppers The variety and assortment of products offered by the typical wellness, beauty and lifestyle (WBL) retailer are wide-ranging. It also offers a deep and wide product assortment in respect of many products. According to Maline (1995: 101) WBL store shoppers most important factors to patronise a particular store, were knowledgeable staff, competitive pricing and onestop shopping. WBL consumers spend most time in-store time reading health/nutrition information to help them in their food-buying decisions (Nayga, Lipinski and Savur, 1998: 107; Nayga, 1996). Given the amount of information collected before the buying-decision and particularly the importance of knowledgeable staff one expects the retail mix dimension termed Personal Interaction to be vital in consumers long term loyalty to a WBL-retailer. P4 : In a WBL-store environment customer loyalty will be determined by personal interaction, merchandise variety, complaint handling and merchandise value Figure 1 is a summary of the store involvement measures that are likely to contribute to the formation of store loyalty. A distinction is drawn between store type and retail mix measures that are expected to address low to high involvement. The vital components of competition differ for low and high involvement: its expected that products that demand more involvement, will also initiate value-added competition as opposed to price competition only. Figure 1 Continuum of Customer Involvement and Various In-Store Shopping Dimensions per Retailer Type

Superstore

Supermarket

Clothing store

WBL Store

Personal interaction Personal interaction Merchandise value Merchandise value Store environment Merchandise value Merchandise variety Complaint handling Merchandise value

Low involvement

High involvement Value-added competition

Price competition

Methodology Sampling A combination of convenience and random sampling was used for collecting the data. For the supermarket and superstore, respondents were drawn from the customers of two superstores

Page - 6 - of 9

ANZMAC

and eight supermarket branches of a retailer that operates nationally. Some 320 superstore and 1244 supermarket customers were interviewed. The clothing store respondents were customers of 11 branches of a national clothing retailer and 2 074 clothing shop customers were interviewed. The questionnaire was mailed to 34 000 WBL-store customers. Data collection and measurement scales Data were collected by means of personal interviews using a structured questionnaire for the supermarket, superstore and clothing customers. For the WBL-store a total of 3181 usable questionnaires were returned, for a response rate of 9.4%. All the respondents were requested to register their level of satisfaction with the retail mix at the particular retailer on a 7-point Likert-type scale. The questionnaire used in the surveys measured the following five retail mix dimensions: Personal Interaction (5 items), Merchandise Value (5 items), Merchandise Variety (4 items), Internal Store Environment (5 items), and Complaint Handling (3 items). Table 1 Reliability Results: Cronbach Alpha Co-Efficients Dimension/Scale Personal interaction Merchandise value Complaint handling Internal store environment Merchandise variety and assortment Retail mix scale Loyalty Superstore ,89 ,86 ,88 ,89 ,90 ,96 ,92 Supermarket ,87 ,84 ,82 ,86 ,86 ,95 ,88 Clothing store ,87 ,84 ,79 ,85 ,84 ,95 ,89 WBL store ,93 ,85 ,89 ,88 ,89 ,95 ,90

The Cronbach Alpha values for the retail mix dimensions and scale and loyalty scale (Table 1) confirm that the instruments used in the study were reliable regardless of the retail type under consideration. The retail mix and loyalty measures were then subjected to a series of confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) to test the measurement model as recommended by Gerbing and Anderson (1988). The CFA results are set out in Table 2. The fit measures reported in Table 2 meet or exceed the minimum levels normally regarded as cut-off points.

Table 2 Fit Indices of the Involvement-Loyalty Model for the Different Retailers Fit indices Degrees of freedom Satorra-Bentler chi-square RMSEA GFI AGFI Superstore 199 299.15 (p=0.0) 0.040 0.85 0.80 Supermarket 199 508,26 (p=0.0) 0,035 0,92 0,89 Clothing WBL retailer store 199 199 809,39 (p=0.0) 819.75 (p=0.0) 0,038 0.031 0,93 0.91 0,91 0.89

Empirical Findings and Conclusions

Page - 7 - of 9

ANZMAC

To address the propositions formulated above, the relationships between the five retail mix dimensions and the dependent variable (loyalty) were assessed by means of a SEM analysis. Loyalty was measured with a three item instrument based on Zeithaml, Berry and Parasuraman (1996); Sirohi et al., (1998) and East et al. (2000). Figure 2 shows the different impacts of the five retail mix dimensions on loyalty. Figure 2 Relationships between the Retail Mix Dimensions and Loyalty for Different Retail Stores

PERSON PERSON

STENV

STENV

VAROS

NS

LOYALTY

VAROS

LOYALTY

MEVAL

MEVAL

COHAN

COHAN

SUPERMARKET

SUPERSTORE

PERSON PERSON

STENV STENV

VAROS

NS

VAROS

LOYALTY

LOYALTY

MEVAL MEVAL

COHAN COHAN

CLOTHING STORE

WBL STORE

In the supermarket study the only significant relationship was that between merchandise value and loyalty. Proposition 1 is thus accepted. The impact of merchandise value on loyalty is highly significant. This study confirmed the price sensitivity of supermarket shoppers. In the superstore study a significant relationship was also found between merchandise value and customer loyalty. Proposition 2 is thus accepted. The reason for relationship is similar to that of the supermarket study. Three of the five retail mix dimensions were found to have a significant impact on loyalty in the clothing study. In line with expectations (Proposition 3), personal interaction and store environment, impacted positively on loyalty with store environment having the stronger impact of the two. The merchandise value dimension, however, has the strongest impact on loyalty. In the WBL sample four of the five independent variables namely personal interaction, merchandise variety, merchandise value and customer complaint handling all impacted on loyalty. Proposition 4 is thus accepted. Managerial Implications The empirical results reported here provide considerable support for the store involvement literature. In other words, the retail mix a retailer offers will address differing levels of consumer involvement which will lead to a differential impact on customer loyalty. What generates loyalty will be different for different types of retailers. The empirical results reported here suggest that a retailer that wishes to enhance customer loyalty will have to pay close attention to how its customers view its retail mix decisions.

Page - 8 - of 9

ANZMAC

References Beharrell, B. and Denison, T., 1995. Involvement in a routine food shopping context. British Food Journal, 97 (4), 24-29. Chattopadhyay, A. and Alba, J.W., 1988. The situational importance of recall and inference in consumer decision making. Journal of Consumer Research, 15 (1), 1-12. Davies, F.M., Goode, M.M.H., Moutinho, L.A. and Ogbonna, E., 2001. Critical factors in consumer supermarket shopping behaviour: A neural network approach. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 1 (1), 35-49. De Klerk, H.M.; Velleman, A.K. and Malherbe, E., 1998. n Kwalitatiewe ondersoek na die invloed van aspekte van die klerewinkel en die verdoopsdame se voorkoms op die damesklereverbruiker se besluitnemingsproses. Journal of Family Ecology and Consumer Sciences, 26 (1), 15-26. Dekimpe, M.G., Steenkamp, J-B.E.M., Mellens, M. and Vanden Abeele, P., 1997. Decline and variability in brand loyalty. International Journal of Research in Marketing. 14 (5), 405-420. Dick, A.S. and Basu, K., 1994. Customer loyalty: Towards an integrated framework. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 22 (2), 99-113. East, R., Hammond, K., Harris, P. and Lomax, W., 2000. First-store loyalty and retention. Journal of Marketing Management, 16, 307-325. East, R., Harris, P., Willson, G. and Lomax, W., 1995. Loyalty to supermarkets. International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research, 5 (1), 99-109. Gerbing, D. W. and Anderson, J.C., 1988. An updated paradigm for scale development incorporating unidimensionality and its assessment. Journal of Marketing Research, 25 (2), 186-192. Goldsmith, R. and Emmert, J., 1991. Measuring product category involvement: a multitraitmultimethod study. Journal of Business Research, 23 (4), 363-371. Mahoney, M.Y. and Sternquist, B., 1989. Perceptions of the discount retailer : an analysis of consumers and managers ideal discount store. Journal of Consumer Studies and Home Economics, 13, 101-111. Maline, N., 1995. How well do you know your customer? An exclusive Drug Store News survey shines the spotlight on todays drug store shopper. Drug Store News, 17 (9), 101. Martin, C.L., 1998. Relationship marketing: A high-involvement product attribute approach. Journal of Product and Brand Management, 7 (1), 6-26. Mellens, M., Dekimpe, M.G. and Steenkamp, J-B.E.M., 1996. A review of brand-loyalty measures in marketing. Tijdschrift voor Economie en Management, 41 (4), 507-533. Mittal, B., 1989. Measuring purchase-decision involvement. Psychology and Marketing, 6 (2), 147-162. Nayga, R.M. (Jr), Lipinski, D. and Savur, N., 1998. Consumers use of nutritional labels while food shopping and at home. The Journal of Consumer Affairs, 32 (1), 106-120. Nayga, R.M. (Jr)., 1996. Determinants of consumers use of nutritional information on food packages. Journal of Agricultural and Applied Economics, 28 (2), 303-312. Park, W.C., Iyer, E.S. and Smith, C., 1989. The effects of situational factors on in-store grocery shopping behaviour: the role of store environment and time available for shopping. Journal of Consumer Research, 15 (4), 422-433. Quester, P.G., Karunaratna, A. and Lim, A.L., 2001. The product involvement/brand loyalty link: An empirical examination. Proceedings of the ANZMAC Conference, Auckland, New Zealand.

Page - 9 - of 9

ANZMAC

Richins, M.L., Bloch, P.H. and McQuarrie, E.F., 1992. How enduring and situational involvement combine to create involvement responses. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 1 (2), 143-153. Sirohi, N., McLaughlin, E.W. and Wittink, D.R., 1998. A model of consumer perceptions and store loyalty intentions for a supermarket retailer. Journal of Retailing, 74 (2), 223-245. Sivadas, E. and Baker-Prewitt, J.L., 2000. An examination of the relationship between service quality, customer satisfaction, and store loyalty. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 28 (2), 73-82. Terblanche, N.S. and Boshoff, C., 2006. A generic instrument to measure customer satisfaction with the controllable elements of the in-store shopping experience. South African Journal of Business Management, 37 (3), 1-14. Thorpe, D.I. and Avery, C.E., 1983. A demographic and psychographic assessment of a specialty stores customers and non customers. Clothing and Textiles Research Journal, 2, 35-41. Torres, I.M., Summers, T.A. and Belleau, B.D., 2001. Mens shopping satisfaction and store preferences. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 8 (4), 205-212. Traylor M.B., 1981. Product involvement and brand commitment: Not necessarily the same. Journal of Advertising Research, 21 (December), 51-56. Venkatraman, M., 1989. Involvement and risk. Psychology and Marketing, 6 (3), 229-247. Zaichkowsky, J.L., 1985. Measuring the involvement construct. Journal of Consumer Research, 12 (3), 341-352. Zeithaml, V.A., Berry, L.L. and Parasuraman, A., 1996. The behavioral consequences of service quality. Journal of Marketing, 60 (2), 31-46.

You might also like

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Ad TestingDocument16 pagesAd TestingJagamohan OjhaNo ratings yet

- Initiatives: Financial Inclusion and Financial Literacy: Andhra Bank'sDocument8 pagesInitiatives: Financial Inclusion and Financial Literacy: Andhra Bank'sJagamohan OjhaNo ratings yet

- Summary - Marketing ResearchDocument36 pagesSummary - Marketing ResearchVibhore BansalNo ratings yet

- Human Resource Information SystemDocument14 pagesHuman Resource Information SystemJagamohan OjhaNo ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (120)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- 1id Abstracts Season 2 Episode 6Document406 pages1id Abstracts Season 2 Episode 6Jennifer BrownNo ratings yet

- Embedded Software Development ProcessDocument34 pagesEmbedded Software Development ProcessAmmar YounasNo ratings yet

- Eng03 Module Co4Document14 pagesEng03 Module Co4Karl Gabriel ValdezNo ratings yet

- Royal British College Dancesport TeamDocument10 pagesRoyal British College Dancesport TeamAnna rose CabatinganNo ratings yet

- Coal Mining Technology and SafetyDocument313 pagesCoal Mining Technology and Safetymuratandac3357No ratings yet

- ENSC1001 Unit Outline 2014Document12 pagesENSC1001 Unit Outline 2014TheColonel999No ratings yet

- All Nobel Prizes in LiteratureDocument16 pagesAll Nobel Prizes in LiteratureMohsin IftikharNo ratings yet

- Hackerearth Online Judge: Prepared By: Mohamed AymanDocument21 pagesHackerearth Online Judge: Prepared By: Mohamed AymanPawan NaniNo ratings yet

- Nursing Assessment in Family Nursing PracticeDocument22 pagesNursing Assessment in Family Nursing PracticeHydra Olivar - PantilganNo ratings yet

- QF Jacket (Drafting & Cutting) - GAR620Document15 pagesQF Jacket (Drafting & Cutting) - GAR620abdulraheem18822No ratings yet

- Adolescents' Gender and Their Social Adjustment The Role of The Counsellor in NigeriaDocument20 pagesAdolescents' Gender and Their Social Adjustment The Role of The Counsellor in NigeriaEfosaNo ratings yet

- NauseaDocument12 pagesNauseakazakom100% (2)

- Masking Conventional Metallic Cast Post For Enhancing EstheticsDocument5 pagesMasking Conventional Metallic Cast Post For Enhancing EstheticsleilyanisariNo ratings yet

- Exemption in Experience & Turnover CriteriaDocument4 pagesExemption in Experience & Turnover CriteriaVivek KumarNo ratings yet

- Unit 20: TroubleshootingDocument12 pagesUnit 20: TroubleshootingDongjin LeeNo ratings yet

- Chain: SRB Series (With Insulation Grip)Document1 pageChain: SRB Series (With Insulation Grip)shankarNo ratings yet

- Grua Grove 530e 2 Manual de PartesDocument713 pagesGrua Grove 530e 2 Manual de PartesGustavo100% (7)

- Writing About Graphs, Tables and DiagramsDocument68 pagesWriting About Graphs, Tables and DiagramsLangers BastasaNo ratings yet

- Pull Cord Switch JayashreeDocument1 pagePull Cord Switch JayashreeNCNo ratings yet

- PretestDocument8 pagesPretestAlmonte Aira LynNo ratings yet

- MSDS Leadframe (16 Items)Document8 pagesMSDS Leadframe (16 Items)bennisg8No ratings yet

- The Handmaid's TaleDocument40 pagesThe Handmaid's Taleleher shahNo ratings yet

- The Other Twelve Part 1Document5 pagesThe Other Twelve Part 1vv380100% (2)

- A Detailed Lesson PlanDocument5 pagesA Detailed Lesson PlanIsaac-elmar Agtarap74% (23)

- On The Wings of EcstasyDocument79 pagesOn The Wings of Ecstasygaya3mageshNo ratings yet

- HAF350A User ManualDocument14 pagesHAF350A User ManualUEENo ratings yet

- 2017LR72 - SUMMARY REPORT Final 03052020Document72 pages2017LR72 - SUMMARY REPORT Final 03052020Dung PhamNo ratings yet

- CLT Apllications NewestDocument49 pagesCLT Apllications NewestMackBrideNo ratings yet

- Action Plan in T.L.E Project Title Objectives Activities Person-In-Charge Time Frame Success IndicatorDocument1 pageAction Plan in T.L.E Project Title Objectives Activities Person-In-Charge Time Frame Success IndicatorEdelmar BenosaNo ratings yet

- Bhavesh ProjectDocument14 pagesBhavesh ProjectRahul LimbaniNo ratings yet