Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Jiabs 30.1-2

Uploaded by

JIABSonline100%(2)100% found this document useful (2 votes)

1K views344 pagesJIABS

Original Title

JIABS 30.1-2

Copyright

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentJIABS

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

100%(2)100% found this document useful (2 votes)

1K views344 pagesJiabs 30.1-2

Uploaded by

JIABSonlineJIABS

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 344

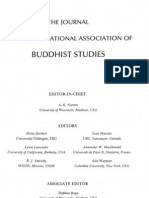

JIABS

Journal of the International

Association of Buddhist Studies

Volume 30 Number 12 2007 (2009)

The Journal of the International

Association of Buddhist Studies (ISSN

0193-600XX) is the organ of the

International Association of Buddhist

Studies, Inc. As a peer-reviewed journal,

it welcomes scholarly contributions

pertaining to all facets of Buddhist

Studies.

JIABS is published twice yearly.

Manuscripts should preferably be sub-

mitted as e-mail attachments to:

editors@iabsinfo.net as one single le,

complete with footnotes and references,

in two dierent formats: in PDF-format,

and in Rich-Text-Format (RTF) or Open-

Document-Format (created e.g. by Open

O ce).

Address books for review to:

JIABS Editors, Institut fr Kultur- und

Geistesgeschichte Asiens, Prinz-Eugen-

Strasse 8-10, A-1040 Wien, AUSTRIA

Address subscription orders and dues,

changes of address, and business corre-

spondence (including advertising orders)

to:

Dr Jrme Ducor, IABS Treasurer

Dept of Oriental Languages and Cultures

Anthropole

University of Lausanne

CH-1015 Lausanne, Switzerland

email: iabs.treasurer@unil.ch

Web: http://www.iabsinfo.net

Fax: +41 21 692 29 35

Subscriptions to JIABS are USD 40 per

year for individuals and USD 70 per year

for libraries and other institutions. For

informations on membership in IABS, see

back cover.

Cover: Cristina Scherrer-Schaub

Font: Gandhari Unicode designed by

Andrew Glass (http://andrewglass.org/

fonts.php)

Copyright 2009 by the International

Association of Buddhist Studies, Inc.

Print: Ferdinand Berger & Shne

GesmbH, A-3580 Horn

EDITORIAL BOARD

KELLNER Birgit

KRASSER Helmut

Joint Editors

BUSWELL Robert

CHEN Jinhua

COLLINS Steven

COX Collet

GMEZ Luis O.

HARRISON Paul

VON HINBER Oskar

JACKSON Roger

JAINI Padmanabh S.

KATSURA Shry

KUO Li-ying

LOPEZ, Jr. Donald S.

MACDONALD Alexander

SCHERRER-SCHAUB Cristina

SEYFORT RUEGG David

SHARF Robert

STEINKELLNER Ernst

TILLEMANS Tom

JIABS

Journal of the International

Association of Buddhist Studies

Volume 30 Number 12 2007 (2009)

Obituaries

Georges-Jean PINAULT

In memoriam, Colette Caillat (15 Jan. 1921 15 Jan. 2007) . . . . . . 3

Hubert DURT

In memoriam, Nino Forte (6 Aug. 1940 22 July 2006) . . . . . . . . . . 13

Erika FORTE

Antonino Forte List of publications . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17

Articles

Tao JIN

The formulation of introductory topics and the writing of

exegesis in Chinese Buddhism . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 33

Ryan Bongseok JOO

The ritual of arhat invitation during the Song Dynasty: Why

did Mahynists venerate the arhat? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 81

Chen-Kuo LIN

Object of cognition in Digngas lambanaparkvtti: On

the controversial passages in Paramrthas and Xuanzangs

translations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 117

Eviatar SHULMAN

Creative ignorance: Ngrjuna on the ontological signi-

cance of consciousness . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 139

Sam VAN SCHAIK and Lewis DONEY

The prayer, the priest and the Tsenpo: An early Buddhist

narrative from Dunhuang . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 175

CONTENTS 2

Joseph WALSER

The origin of the term Mahyna (The Great Vehicle) and

its relationship to the gamas . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 219

Buddhist Studies in North America

Contributions to a panel at the XVth Congress of the International

Association of Buddhist Studies, Atlanta, 2328 June 2008

Guest editor: Charles S. Prebish

Charles S. PREBISH

North American Buddhist Studies: A current survey of the eld . . 253

Jos Ignacio CABEZN

The changing eld of Buddhist Studies in North America . . . . . . . . 283

Oliver FREIBERGER

The disciplines of Buddhist Studies Notes on religious

commitment as boundary-marker. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 299

Luis O. GMEZ

Studying Buddhism as if it were not one more among the

religions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 319

Notes on contributors. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 345

In memoriam

COLETTE CAILLAT

(15 Jan. 1921 - 15 Jan. 2007)

GEORGES-JEAN PINAULT

International Indology has suffered a great loss by the demise of

Prof. Dr. Colette Caillat, precisely on her eighty-sixth birthday,

15 January 2007. She had contacts and friendly relationships with

scholars of Indian studies allover the world, especially in her field

of expertise: Jaina and Buddhist studies and Middle Indo-Aryan

linguistics, not excluding other topics, as classical Sanskrit litera-

ture and Indian culture in general. 1 may refer to obituaries that

have been already published for full information about her career

and publications.! I would like to stress shortly some important

facts. On one hand, the education of Colette Caillat is deeply root-

ed in the French humanist tradition, which is based on the study of

classical languages (Latin and Greek), and masterworks of French

and world literature: her interest for Sanskrit was initially con-

nected with comparative Indo-European linguistics, but the French

lndology of the 1930s and 1940s had developed a keen interest for

the study of Indian languages and literature in the larger context

of India and South Asia, that is in their native milieu. Her teach-

ers, whose merits she was never reluctant to recognize, were Louis

1 See Indo-Iranian Journal 50, 2007, pp. 1-4 (by Minoru Rara); Bulletin

d'Etudes Indiennes 22-23, 2004-2005 [published in June 2007], pp. 23-70

(by Nalini Balbir, with full bibliography, including the reviews); The Jour-

nal of Jaina Studies (Japan), Vol. 13, September 2007, pp. 77-90 (by Nalini

Balbir, with list of papers related specifically to Jaina studies); Indologica

Taurinensia, VoL XXXIII, 2007, pp. 167-182 (by Nalini Balbir, with list of

books and articles published between 1988 and 2007); Journal Asiatique

295.1,2007, pp. 1-7 (by Nalini Balbir).

Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies

Volume 30 Number 1-2 2007 (2009) pp. 3-11

4

GEORGES-JEAN PINAULT

Renou (1896-1966), who had the deepest knowledge of the Vedas,

of Pat;lini and of the literary genres of classical Sanskrit, and Jules

Bloch (1880-1953), who drew the attention of his audience to the

whole history of Indo-Aryan, with Pali and Prakrits as intermedi-

ates, and to all aspects of Indian material and non-material cul-

ture. This latter influence explains why Colette Caillat learned, iii.

addition to Sanskrit and Middle Indo-Aryan languages, Hindi at

the School of Oriental Languages ("Langues Orientales") in Paris.

On the other hand, Colette Caillat has been from the beginnings

of her research on Jaina literature at the level of international re-

search in Indology, through the decisive collaboration with Walther

Schubring (1881-1969) in Hamburg, to Whom she was addressed

by Louis Renou, because nobody in France was proficient in the

texts of the Jaina tradition. Later, again under the recommendation

of Schubring, she became a collaborator of the Critical PaIi Dic-

tionary, an international venture based on the highest philological c

standards, the publication of which started in 1924. One should add

that she visited India for the first time in 1963, and that she worked

regularly there over the years, especially in Mysore and Ahmeda-

bad, being in friendly contacts with Jaina scholars. Therefore,

Colette Caillat has been able to combine her European scholarly

education with open-mindedness for the Indian culture, including

its contemporary aspects, but she never forgot the rational and his-

torical approach, that is based ultimately on the influential doctrine

Meillet (1866-1936), linking linguistics with social and

cultural history.

All works of Colette Caillat are characterized by great accuracy

in philological matters, lucidity of exposition, and high sensibility

to the texts. One should add Common sense, which is not the qual-

ity that is most frequently met among great Indologists. Accord-

ingly, her researches on the vocabulary and on minute details of

grammar were conceived as tools for understanding with the best

exactness the way of thinking of Indian authors of the past. This

method is certainly welcome for the understanding of literatures

that play consciously with the potentialities of the language itself.

COLETTE CAILLAT (15 Jan. 1921 - 15 Jan. 2007)

5

Colette Caillat has made a great contribution to a wider knowledge

of the Jaina religion and literature. As a matter of fact, she has

also emphasized the links between Jaina and Buddhist traditions,

despite their independence, on the linguistic as well as on the doc-

trinal side. Her doctoral thesis about the Atonements in the Ancient

Ritual of the Jaina Monks (1965)2 remains a masterpiece, since she

was able in a luminous style to disentangle a complicated doctrine

from the texts themselves and to explain it in a wider context, that

makes the difficult matter understandable for every humanist.

The bibliography of Colette Caillat is quite impressive: nine

personal books, mostly on Jaina texts, direction of eight books,3

around 90 articles and 190 reviews in various journals. I can testify

that Colette Caillat, since the beginning of her career, has read in

depth and annotated many works of Indologists of present and past

time. Therefore, every statement from her pen is based on long-

time thinking, pondering and immense learning. I remember that

she has followed with passion all advances about the interpretation

of the edicts of Asoka that remain a turning point of Indian lin-

guistic and cultural history. She said also that she never hesitated to

immerse herself in the monumental edition of the Gandhari Dhar-

mapada by John Brough (1962). It is no surprise that she has been

much interested in the past years in the publication of manuscripts

from several collections that emerged from the Gandhara region.

In some sense, her teaching and original contributions helped to

fully appreciate under the best angle the relevance of these doc-

uments for the history of Buddhism, which, in addition to their

intrinsic linguistic import, committed to oblivion some rash ear-

2 Date of the original publication in French; English translation published

in Ahmedabad, 1975.

3 Some of them are proceedings of conferences; others are editions of the

works of her teachers: Jules Bloch, Application de la cartographie a l' histoire

de l'indo-aryen, in collaboration with Pierre Meile, specialist of Dravidian

(Paris, 1963); Recueil d' articles de Jules Bloch 1906-1955 (Paris, 1985);

Louis Renou, Etudes vediques et palJineennes, t. XVII (Paris, 1969).

6

GEORGES-JEAN PINAUL T

lier generalizations based on less material. As an appendix to this

present memorial, I give a list of her articles devoted to Buddhist

studies and Middle Indo-Aryan linguistics, but I would insist on

the importance of her reviews, from which one can glean many im-

portant insights. To this list should be added the booklet Pour une

nouvelle grammaire du PaZi, Turin, 1970, based on a lecture given

at the Istituto di Indologia dell'Universita di Torino. This modest

publication (around 30 pages) actually paved the way to the ~ i n g u i s

tic interpretation of facts in a larger spectrum, including morphol-

ogy, syntax, derivation, thus replacing the innovations and stylistic

choices ofthe PaIi language into history.4 One of her last works was

the direction of a collective dossier about ancient Buddhism: "Le

bouddhisme ancien sur Ie chemin de l'Eveil. Les vies du Bouddha,

Nobles Verites et Octuple sentier. Philosophie ou religion?" for the

journal Religions & Histoire, Nr. 8, May-June 2006, pp. 12-75. It

testifies to her pedagogical talent in introducing the fundamentals

of the Buddhist way of thinking.

Colette Caillat was quite engaged in the teaching of Indology at

the University: having started her career in Lyon (1960-1965), she

succeeded Louis Renou at the Sorbonne in 1966, and she taught

there until her retirement in 1989. She was convinced that Indian

studies are as demanding as studies of classical languages: they

are worth of a complete course at the university. Her direct pupils

have much benefited from her teaching that was quite stimulating

because of her wide knowledge of all aspects of Indian culture and

of Indology. She was able to share with the audience her curios-

ity and even her love for everything Indian. As a former student,

I will always remember her unique way of pronouncing Pali and

ArdhamagadhI, which helped to communicate the feeling of living

and real languages. She has encouraged young researchers that had

different interests in the large field of Indology. One may say that

4 It has been openly taken into account in the handbook of Middle Indian

published by Prof. Dr. Oskar von Hiniiber, Das altere Mittelindisch im Uber-

blick, Vienna, 1

st

edition 1986, 2

nd

revised edition 2001.

COLETTE CAILLAT (15 Jan. 1921 - 15 Jan. 2007)

7

several (French and non-French) Indologists, while having their

own intellectual aims, owe their degree to her benevolence and her

capacity to form a decent committee for a thesis; she had the abil-

ity to highlight the strong points of a student, while indicating the

weak points if needed. Her influence spread to scholars of other

countries, especially from Japan, where she had many friends,

some of them being former pupils, starting with Prof. Katsumi Mi-

maki (Kyoto). One may recall that the latter colleague gave the

name Kaya ("perfume" in Japanese) to his daughter, born 1977,

as a reminder of his Parisian teacher. While having strong convic-

tions, and being quite sympathetic towards modern trends, Colette

Caillat was both fair and friendly, and she never compromised firm

ethical principles. These personal features explain her wide influ-

ence and her role in several academic institutions, learned journals

and international committees; she served as treasurer of the In-

ternational Association for Sanskrit Studies (1977-2000), and she

was elected to the Presidency of the International Association of

Buddhist Studies (1999-2002). She conceived indological research

on an international basis, and was opposed to every form of nation-

alism, which turns often to chauvinism or sectarianism. She was

open to all sound advances in Indology; one could also say that she

could express a typical French irony against fuss and overstate-

ment, which belong to the usual pathology of scholarship. She was

very demanding of herself, and she was devoted to the transmis-

sion of the knowledge that she had received from her teachers and

friends, because it remains the basis of every future progress in the

understanding of the contribution of India to the universal culture.

8

GEORGES-JEAN PINAULT

Articles by Colette Caillat on Middle Indo-Aryan and Buddhist stud-

iess

Deux etudes de moyen-indien (1. A propos de pali philsuvihilra, ardhama-

gadhi phasuya-esalJ-ijja ; 2. Sur l' origine de gOlJ-a) , Journal Asiatique 248,

1960, pp. 41-64.

Nouvelles remarques sur les adjectifs moyen-indiens philsu, philsuya ,

Journal Asiatique 249, 1961, pp. 497-502.

Les derives moyen-indiens du type kilrima , Journal Asiatique 253, 1965,

pp. 289-308.

La sequence SHYTY dans les inscriptions indo-arameennes d' Asoka , Jour-

nal Asiatique 255, 1966, pp. 466-470. Following Emile Benveniste & Andre

Dupont-Sommer, Dne inscription indo-arameenne d'Asoka provenant de

Kandahar (Afghanistan) , ibid., pp. 437-465.

La finale -ima dans les adjectifs moyen- et neo-indiens de sens spatial ,

in : Melanges d'indianisme a la memoire de Louis Renou, Paris, De Boc-

card, 1968 (Publications de 1'Institut de Civilisation Indienne, n 28), pp.

187-204.

Isipatana migadaya , Journal Asiatique 256, 1968, pp. 177-183.

Pali ibbha, Vedic {bhya- , in : Lance Cousins et al. (eds.), Buddhist Studies

in honour of I.B. Horner, Dordrecht, D. Reidel, 1974, pp. 41-49.

A propos de sanskrit candrimil- 'clair de lune' , in : Melanges

ques offerts a Emile Benveniste, Paris (Collection Iinguistique pubIiee par la

Societe de Linguistique de Paris, t. 70), 1975, pp. 65-74.

Forms of the Future in the Gilndhilrf Dharmapada , in : Annals of the

Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute, Poona, 1977-1978 (Diamond Jubi-

lee Volume), pp. 101-106.

Pronoms et adjectifs de similarite en moyen indo-aryen , in: Indianisme

et Bouddhisme. Melanges offerts a Mgr. Etienne Lamotte, Louvain-Ia-Neuve,

1980 (Publications de 1'Institut orientaliste de Louvain, n 23), pp. 33-40.

La langue primitive du bouddhisme , in : Heinz Bechert (ed.), The Lan-

guage of the Earliest Buddhist Tradition, Gottingen (Abhandlungen der Aka-

demie der Wissenschaften in Gottingen. Phil.-hist. Kl., 3. FoIge, Nr. 117),

1980, pp. 43-60.

5 A volume of selected papers on this topic is currently in preparation for

publication by the Pali Text Society.

COLETTE CAILLAT (15 Jan. 1921-15 Jan. 2007)

9

Etat des recherches sur les inscriptions d' Asoka , Bulletin d' Etudes In-

diennes 1, 1983, pp. 51-57.

Pali (langue; litterature) , in : Encyclopaedia Universalis, Paris, 1985,

Corpus, t. 13, pp. 986-988.

Prohibited speech and subhasita in the Buddhist Theravada tradition , In-

dologica Taurinensia 12, 1984, pp. 61-73 (Proceedings of the Scandinavian

Conference-Seminar ofIndological Studies, Stockholm, June 1''-5

t

\ 1982).

Notes bibliographiques : quelques publications recentes consacrees aux tra-

ditions manus crites du bouddhisme indien et aux conclusions generales qui

decoulent de leur etude , Bulletin d'Etudes Indiennes 2, 1984, pp. 61-69.

The Condemnation of False - Wrong Speech (musavada) in the Pali Scrip-

tures , in : Tatsuro Yamamoto (ed.), Proceedings of the 31

st

International

Congress of Human Sciences in Asia and North-Africa, Tokyo-Kyoto (31

st

August-7th September 1983), Tokyo, 1984, Vol. 1, pp. 201-202 (resume).

Grammatical Incorrections, Stylistic Choices, Linguistic trends (with ref-

erence to Middle Indo-Aryan) , in: Wolfgang Morgenroth (ed.), Sanskrit

and World Culture. Proceedings of the 4th World Sanskrit Conference (Wei-

mar, 1979), Berlin, Akademie Verlag, 1986 (Schriften zur Geschichte und

Kultur des Alten Orients, Nr. 18), pp. 367-373.

Sur l'authenticite linguistique des edits d' Asoka , in: Colette Caillat (ed.),

Dialectes et formes dialectales dans les litteratures indo-aryennes. Actes du

colloque international, Paris, De Boccard, 1986 (Publications de l'Institut de

Civilisation Indienne, nO 55), pp. 413-432.

The constructions mama krtam and mayii krtam in Asoka's edicts , in:

Albrecht Wezler & Ernst Hammerschmidt (eds.), Proceedings of the XXXII

International Congress of Asian and North African Studies (Hamburg, 25

th

-30

th

August 1986), Stuttgart, Franz Steiner Verlag, (ZDMG, Supplement

IX), 1992, p. 489.

Some idiosyncrasies oflanguage and style in Asoka's Rock Edicts at Gir-

nar , in: Harry Falk (ed.), Hinduismus und Buddhismus. Festschriftfur Ul-

rich Schneider, Freiburg, 1987, pp. 87-100.

Vedic ghraf!!sa- 'heat' of the sun, ArdhamagadhI ghif!!sU 'burning heat',

Jaina M a h a r a ~ t r I ghif!!_o 'hot season', in: Annals of the Bhandarkar Ori-

ental Research Institute 68 [Ramakrishna Gopal Bhandarkar 150th Birth-

Anniversary Volume], 1987, pp. 551-557.

Aspects de 1'epigraphie dans l' Asie du Sud et du Sud-Est , Comptes ren-

dus de I'Academie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres, 1988, 4

e

fascicule, pp.

10

GEORGES-JEAN PINAUL T

1-12 (communication prononcee dans la seance publique annuelle du 18 no-

vembre 1988).

Notes grammaticales sur les documents de Niya , in : Akira

Haneda (ed.), Documents et archives provenant de I'Asie centrale. Actes du

colloque franco-japonais (Kyoto, 4-8 octobre 1988), Kyoto, Societe Franco-

Japonaise des Etudes Orientales, 1990, pp. 9-24.

Asoka et les gens de la brousse (XIII M-N) "qu'ils se repentent et cessent

de tuer", Bulletin d'Etudes Indiennes 9, 1991, pp. 9-13.

The 'double optative suffix' in Prakrit Asoka XIII (N) na hartmesu/na

haiiiieyasu , in: Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute

[Amrtamahotsava Volume] 72-73 (1991-1992), 1993, pp. 637-645.

Connections between Asokan (Shahbazgarhi) and Niya Prakrit? , Indo-

Iranian Journal 35, 1992, p. 109-119.

Deux notes de moyen indo-aryen. I. Les quatre themes de present de HAN-

en pali. II. 'Double optatif' en jaina ? , Bulletin d' Etudes Indien-

nes 10, 1992, pp. 97-111.

Doublets desinentiels en moyen indo-aryen , in : Reinhard Sternemann

(ed.), Bopp-Symposium 1992 der Humboldt-Universitiit zu Berlin (Akten der

Konferenz vom 24.3.-26.3.1992), Heidelberg, Universitatsverlag Carl Win-

ter, 1994, pp. 35-52.

Vedic and Early Middle Indo-Aryan , in : Michael Witzel (ed.), Inside the

texts, beyond the texts. New approaches to the study of the Vedas. Proceed-

ings of the International Vedic Workshop (Harvard University, June 1989),

Cambridge (Mass.), Harvard Oriental Series (Opera Minora, Vol. 2), 1997,

pp.15-32.

L'appel de la Loi ou l'age transcende , in : Christine Chojnacki (ed.), Les

ages de la vie dans Ie monde indien. Actes des journees d'etude de Lyon

(22-23 juin 2000), Lyon, 2001 (Collection du Centre d'Etudes et de Recher-

ches sur l'Occident Romain. Nouvelle serie, nO 24), pp. 325-332.

Gleanings from a Comparative Reading of Early Canonical Buddhist and

Jaina Texts , Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies

26/1,2003, pp. 25-50.

Manuscrits bouddhiques du Gandhara , Comptes rendus de l'Academie

des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres, janvier-mars 2003, pp. 453-460.

L'epoque du Bouddha et la diffusion du bouddhisme , La doctrine des

Anciens (Thera-vada) , in : Religions & Histoire, n08, mai-juin 2006, pp.

14-17,36-42.

COLETTE CAILLAT (15 Jan. 1921 - 15 Jan. 2007)

11

Articles in the Critical Piili Dictionary (CPD), Copenhagen, in Volume

II, from fascicle 7 (1971) to fascicle 15 (1990) : is-issayitatta, uddha-unnltaka,

upatapeti-upananda-sakyaputta, ekato-ekavasa, etadI-etava(ta), ettaka-ettavata,

edI-edisaka.

Reviews of fascicles of the CPD : Indogermanische Forschungen 71, 1966,

pp. 306-309 ; 74, 1969, pp. 223-225 ; 75, 1970, pp. 299-303 ; 78, 1973, pp.

247-249 ; 79, 1974, pp. 250-255 ; 81, 1976, pp. 327-329 ; 88, 1983, pp. 312-318 ;

Bulletin de la Societe de Linguistique de Paris 66/2, 1971, pp. 66-67 ; Comptes

rendus de l'Academie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres 1992, pp. 689-691.

In memoriam

NINO FORTE

(6 Aug. 1940 - 22 July 2006)

HUBERT DURT

Antonino Forte, who passed away in his beloved Kyoto during the rainy

season of 2006, was a pioneer in a new approach to Buddhist studies.

This approach cannot be separated from the Sicilian background of this

Sinologist and Historian born in Cefalu. Sicilian writers, and especially

the novelist Leonardo Sciascia who in his essays tried to define the spirit

of the island, were obsessed with the weight of the power of institutions,

or pseudo-institutions, hanging over the shoulders of a population com-

posed much more of country people than of seafarers. In the rather indo-

lent world of studies on Chinese Buddhism the title of the first book of A.

Forte, and in its revised version his last, Political Propaganda and Ideol-

ogy in China at the End of the Seventh Century, sounded like a gun shot.

"Propaganda" is a despised term, and so also, in a somewhat reduced

measure, is the term "ideology."

Opening the book, the reader is faced with a survey made with intense

scrupulousness, but also with much clarity, which unravels a double mach-

ination whose effects have persisted for almost thirteen centuries. The

first machination consisted in offering, by a group of eminent representa-

tives of the Buddhist clergy at the end of the first Tang age, of a pseudo

commentary on the well-known Great-Cloud Sutra (Mahiimeghasutra,

Dayunjing). This Indian Mahayanic sutra contains several prophetic ele-

ments, and the pseudo-commentary, found in the early twentieth century

among Dunhuang manuscripts, was intended to support the founding of

the Zhou dynasty (690-705) by Empress Wu. The commentary then dis-

appeared with the collapse of the ephemeral Zhou era.

Forte's outstanding annotated translation of the commentary forms

the second part of the book. But there was a second machination. After

the Zhou dynasty was abolished, the official (and sometimes Buddhist)

historiography of the second Tang age and following periods darkened

the memory of Empress Wu. This resulted in numerous misunderstand-

ings which were renewed when modern historians, mostly Chinese and

Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies

Volume 30 Number 1-22007 (2009) pp. 13-15

14

HUBERTDURT

Japanese, attempted a new evaluation of the troubled, but for many rea-

sons brilliant, reign of Empress Wu.

Much of the scholarly production of Forte was devoted to that short

but extremely important period of Chinese history, where we see a reign-

ing woman topple several taboos and initiate what could be considered

a Chinese enlightened policy. Forte's choice to concentrate on Chinese

Buddhist "ecclesiastical" documents, and especially on epigraphy, has

made his work extremely original and creative.

Following his seminal Political Propaganda, first published ip Naples

in 1976 and completely revised in the new edition of the Kyoto Italian

School of East Asian Studies, another major contribution on the Empress

Wu period was Forte's Mingtang and Buddhist Utopias in the History of

the Astronomical Clock. The Tower, Statue and Armillary Sphere Con-

structed by Empress Wu, jointly published by the EFEO of Paris and by

the IsMEO of Rome in 1988. In connection with these works, several of

Forte's articles deal with religious figures contemporary to Empress Wu:

Buddhist (including a monograph on Fazang's letter to Uisang) or non-

Buddhist as the Persian Aluohan (616-710).

Another book, which was also co-produced, this time by the Italian

School of East Asian Studies in Kyoto and the College de France in Paris,

was the edition of an unfinished study of Paul Pelliot, L'inscription ne-

storie nne de Si-ngan-fou in 1996. With the help of his indefatigable wife

Lilla, Forte not only edited and completed Pelliot's work, but he also

contributed no less than five appendices (pp. 349-495), which mark his

foray into the post-Wu period of the Tang dynasty. Furthermore, he un-

dertook some investigations on the Persian and Manichean relations of

the Tang empire, some of which have deep roots in the past, as shown by

his. everlasting interest in the archaic translator An Shigao (fl. ca. A.D.

148-170).

The magisterial and very homogenous scholarly written heritage left

by Antonino Forte is far from representative of the totality of his ac-

tivities. His various undertakings at his Alma Mater, the Istituto Uni-

versitario Orientale of Naples, currently called Universita degli Studi di

Napoli "L'Orientale," and at the Institut du H6b6girin of Kyoto, where

he was sent by the leader and inspirer of the H6b6girin Dictionary, Paul

Demieville, were the platform from which he later launched his major

projects, when he started the Italian School of East Asian Studies in

Kyoto, as its first and long-time director. His activities took, amongst oth-

ers, three special directions: the study of Chinese religious epigraphy,

the Italo-Chinese collaboration for the study of Longmen, and the Italo-

NINO FORTE (6 Aug. 1940 - 22 July 2006)

15

Japanese collaboration for the study of the Buddhist Canon kept at the

Nanatsuderain Nagoya.

Having known Nino Forte since 1964 (in Bordeaux), I keep the fond

memory of a friend with a warm smile, whose passion for research im-

mediately attracted to him the support of a plead of eminent Masters:

the already mentioned Paul Demieville, Giuseppe Tucci, Tsukamoto

Zenryu, and Makita Tairyo. Later (1976-1984), we became colleagues at

the Ecole d'Extreme-Orient in Kyoto. I benefited from his his-

toricallucidity and also from his expertise in computers when this new

technology was introduced into our studies. In the years that followed, I

saw for myself the inspiration he gave to his own students in Naples and

in Kyoto, where he spent close to twenty years, I witnessed his generosity

to students of every nationality engaged in East Asian studies. It would

be difficult not to find warm acknowledgment expressed to Nino Forte in

any work prepared in the stimulating atmosphere of the Italian School of

East Asian Studies during his directorship.

After having studiously spent every summer in Kyoto since his return

to Italy after his first directorship, Nino Forte had just begun a second

period as director in the Spring of 2006, when he sadly was defeated by

cancer. It is Silvio Vita, his able predecessor, who will once again take up

the direction of the School.

Although ultra-specialized in his field, Antonino Forte was not a man

secluded from his time: he was deeply active in the struggle for the pro-

tection of Old Kyoto from financial conspiracies, megalomaniac tenden-

cies, and the lack of consciousness accompanied by irreverence for the

past. He was, moreover, engaged in activities to prevent war in Iraq. In

him, in his wife Lilla, and in their daughter Erika, an archaeologist in the

field of Chinese and Central Asian Studies, I could always see the sacred

fire of devotion to Asia and to world peace.

Books

ANTONINO FORTE - LIST OF PUBLICATIONS

(Compiled by the late Prof. Antonino Forte

and amended by Erika Forte.)

1. Political Propaganda and Ideology in China at the End of the Seventh Cen-

tury. Inquiry into the Nature, Authors and Functions of the Tunhuang Docu-

ment S. 6502, Followed by an Annotated Translation. Istituto Universitario

Orientale, Napoli 1976.

2. Index des caracteres chinois dans les Fascicules I-V du Hobogirin. Mai-

sonneuve, Paris, Maison Franco-Japonaise, Tokyo 1984.

3. Mingtang and Buddhist Utopias in the History of the Astronomical Clock.

The Tower, Statue andArmillary Sphere Constructed by Empress Wu. Istituto

per il Medio edEstremo Oriente (Serie Orientale Roma, vol. LIX), Ecole

Fran9aise d'Extreme-Orient (vol. CXLV), Rome and Paris 1988.

4. The Hostage An Shigao and his Offspring. An Iranian Family in China.

Italian School of East Asian Studies (Occasional Papers 6), Kyoto 1995.

5. A Jewel in Indra's Net. The Letter Sent by Fazang in China to Uisang in

Korea. Italian School of East Asian Studies (Occasional Papers 8), Kyoto

2000.

6. Political Propaganda and Ideology in China at the End of the Seventh

Century. Inquiry into the Nature, Authors and Functions of the Tunhuang

Document S. 6502, Followed by an Annotated Translation (Second Edition).

Italian School of East Asian Studies (Monographs 1), Kyoto 2005.

Edited books

1. Gururajamaiijarika. Studi in onore di Giuseppe Tucci, 2 vols. Istituto Uni-

versitario Orientale, Napoli 1974. (Co-editor with Maurizio Taddei and Luigi

Polese Remaggi.)

2. Tang China and Beyond. Studies on East Asia from the Seventh to the

Tenth Century. Italian School of East Asian Studies (Essays 1), Kyoto 1988.

Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies

Volume 30 Number 1-2 2007 (2009) pp. 17-31

18

ANTONINO FORTE (1940-2006)

3. Maurizio Riotto, The Bronze Age in Korea. A Historical Archaeological

Outline. Italian School of East Asian Studies (Occasional Papers 1), Kyoto

1989.

4. Giuliano Bertuccioli, Travels to Real and Imaginary Lands. Two Lectures

on East Asia. With an Appendix: Francesco Carletti on Slavery and Oppres-

sion, by Antonino Forte. Italian School of East Asian Studies (Occasional

Papers 2), Kyoto 1990.

5. Tonami Mamoru, The Shaolin Monastery Stele on Mount Song. Italian

School of East Asian Studies (Epigraphical Series 1), Kyoto 1990. .

6. Hubert Durt, Problems of Chronology and Eschatology. Four Lectures on

the Essay on Buddhism by Tominaga Nakamoto (1715-1746). Italian School

of East Asian Studies (Occasional Papers 4), Kyoto 1994.

7. Claudio Zanier, Where the Roads met. East and West in the Silk Production

Processes (l7th to 19th Centuries). Italian School of East Asian Studies (Oc-

casional Papers 5), Kyoto 1994.

8. Paul Pelliot, L'inscription nestorienne de Si-ngan-fou. Italian School of

East Asian Studies (Epigraphical Series 2) and College de France, Kyoto and

Paris 1996.

9. Giorgio Amitrano, The New Japanese Novel. Popular Culture and Literary

Tradition in the Work of Murakami Haruki and Yoshimoto Banana. Italian

School of East Asian Studies (Occasional Papers 7), Kyoto 1996.

10. A Life Journey to the East. Sinological Studies in Memory of Giuliano

Bertuccioli (1923-2001). Italian School of East Asian Studies (Essays 2),

Kyoto 2002. (Co-edited with Federico Masini.)

Articles and reviews

1968

1. "An Shih-kao: biografia e note critiche." Annali dell'Istituto Orientale di

Napoli, 28 (1968), pp. 151-194.

1970

2. "La prima opera buddhista delle fonti giapponesi." Il Giappone, X (1970),

pp.43-52.

LIST OF PUBLICATIONS

19

3. Review: Fujishima Tateki "Gench6 K6hi no bukky6 shink6" :7G

IBK 16, 2. pp. 309-313. Revue Bihliographique de Si-

nologie, (1968-1970), p. 311.

1971

4. "11 P'u-sa cheng-chai ching e l'origine dei tre mesi di digiuno prolungato."

T'oung Pao, LVII (1971), pp. 103-134.

5. "The Ching-tu san-mei ching and the Tun-huang Manuscripts" by Tairy6

Makita. East and West, 21.3-4 (September-December 1971), pp. 351-361.

(Annotated translation from Japanese).

1973

6. "11 'Monastero dei grandi Chou' a Lo-yang." Annali dell'Istituto Orientale

di Napoli, 33 (1973), pp. 417-429.

7. "Deux etudes sur Ie manicMisme chinois: 1. Une poesie attribue a Po Chil-

i; II. Le manicMisme dans la region de Wen-chou en 1120." T'oung Pao,

LIX.l-5 (1973), pp. 220-253.

1974

8. "Divakara (613-688), un monaco indiano nella Cina dei T'ang." Annali

della Facolta di lingue e letterature straniere di Ca' Foscari, Ser. Or. 5, XIII

(1974), pp. 135-164.

9. "Un pensatore Vijfianavadin del VII secolo: Hsiian-fan." In Gururiijamaii-

jarikii. Studi in onore di Giuseppe Tucci, edited by Maurizio Taddei, Antoni-

no Forte and Luigi Polese Remaggi, Istituto Universitario Orientale, Napoli

1974, vol. II, pp. 559-570.

1979

10. "Ch6sai *'J1!f" (Prolonged Fast). In Hobogirin Dictionnaire

encyclopedique du Bouddhisme d'apres les sources chinoises et Japonaises,

V (1979), pp. 135-164 (with collaboration of Jacques May).

11. "Le moine Khotanais Devendraprajfia." Bulletin de l'Ecole Franraise

d'Extreme-Orient, LXVI (1979), pp. 289-298.

20

ANTONlNO FORTE (1940-2006)

1980

12. "Additions and Corrections to my Political Propaganda and Ideology in

China at the End of the Seventh Century." Annali dell'Istituto Orientale di

Napoli, 40 (1980), pp. 163-175.

1983

13. "Daiji (Chine)" (Great Monasteries in China). In HabiJgirin rt;)t

Dictionnaire encyclopedique du Bouddhisme d'apres les sources chi-

noises et Japonaises, VI (1983), pp. 682-704.

1984

14. "The Activities in China of the Tantric Master Manicintana (Pao-ssu-wei

?-721) from Kashmir and of his Northern Indian Collaborators." East and

West, 34.1-3 (September 1984), pp. 301-345.

15. "II persiano A1uohan (616-710) nella capita1e cinese Luoyang, sede del

Cakravartin." In Incontro di religioni in Asia tra il III e il X secolo d. c.,

edited by Lionello Lanciotti. Olschki, Firenze 1984, pp. 169-198.

16. "Daiungyasho 0 megutte" (About the Commentary

on the Great-cloud Satra). In Tonka to Chiigoku bukkya q:tOOfJ,.Wc

(Dunhuang and Chinese Buddhism), edited by Makita Tairyo and

Fukui Fumimasa Vol. no. 7 of the series Koza Tonko

DaitO shuppansha Tokyo 1984, pp. 173-206.

1985'

17. "Hui-chih (fl. 676-703 A.D.), a Brahmin Born in China." Annali

dell'Istituto Orientale di Napoli, 45 (1985), pp. 105-134.

18. "Brevi note suI testo kashmiro del Dhiirar;f-satra di AvalokiteSvara

dall'infallibile laccio introdotto in Cina da Manicintana." In Orientalia Iose-

phi Tucci memoriae dicata, edited by Gherardo Gno1i and Lionello Lanciotti,

Istituto Italiano per il Medio ed Estremo Oriente (Serie Orientale Roma, vol.

LVI, 1), Roma 1985, pp. 371-393.

19. "La Secte des Trois stades et l'heresie de Devadatta. Yabuki Keiki corrige

par Tang Yongtong." Bulletin de ecole Franraise d'Extreme-Orient, LXXIV

(1985), pp. 469-476.

20. "Itaria Tohogaku kenkyujo no sosetsu" ..{ y

(The foundation of the School of East Asian Studies in Kyoto). Tah6gaku *

(Eastern Studies), 69 (January 1985), pp. 163-167.

LIST OF PUBLICATIONS

21

21. "The School of East Asian Studies (Tohogaku Kenkyujo) in Kyoto." An-

naZi dell'Istituto Orientale di Napoli, 45 (1985), pp. 357-365.

1986

22. "Scienza e tecnica." In Cina a Venezia. Dalla dinastia Han a Marco Polo.

Electa, Milano 1986, pp. 36-49.

23. "Science and Techniques." In China in Venice. From the Han Dynasty

to Marco Polo. Electa, Milano 1986, pp. 36-49. (English translation of no.

22.)

24. "II buddhismo e Ie altre religioni straniere." In Cina a Venezia. Dalla

dinastia Han a Marco Polo. Electa, Milano 1986, pp. 58-7l.

25. "Buddhism and the Other Foreign Religions." In China in Venice. From

the Han Dynasty to Marco Polo. Electa, Milano 1986, pp. 58-71. (English

translation of no. 24.)

26. Review: Recherches sur les chnfftiens d'Asie Centrale et d'Extreme-

Orient. II, I: La stele de Si-ngandou. Oeuvres Posthumes de Paul Pelliot.

Editions de la Fondation Singer-Polignac, Paris 1984. East and West, 36.1-3

(September 1986), pp. 313-315.

27. "The School of East Asian Studies (Tohogaku Kenkyujo) in Kyoto."

Rivista Internazionale di Scienze Economiche e Commerciali, XXXIII, 5

(maggio 1986), p. 516.

1987

28. Review: Horward J. Wechsler, Offerings of Jade and Silk. Ritual and

Symbol in the Legitimation of the T'ang Dynasty. Yale University Press, New

Haven and London 1985. T'oung Pao, LXXIII.4-5 (1987), pp. 327-340.

1988

29. "Un gioiello della rete di Indra. La lettera che dalla Cina Fazang invio

a Uisang in Corea." In Tang China and Beyond. Studies on East Asia from

the Seventh to the Tenth Century, edited by Antonino Forte, Italian School of

East Asian Studies (Essays 1), Kyoto 1988, pp. 35-83.

1989

30. "Yutian seng Tiyunpanruo" (The Khotanese Monk De-

vendraprajiia). In Xu Zhangzhen (translator), Xiyu yu fojiao wenshi

lunji (A Collection of Literary and Historical Essays

22

ANTONINO FORTE (1940-2006)

Concerning the Western Regions and Buddhism), Xuesheng shuju Jj!1:..fili,

Taipei 1989, pp. 233-246. (Chinese version of no. 11; revised in 1988.)

31. Review: Stanley Weinstein, Buddhism under the T'ang. Cambridge Uni-

versity Press, Cambridge 1987. T'oung Pao, LXXVA-5 (1989), pp. 317-324.

32. Comment (in Japanese) to Nakanishi "Higashi Ajia ni

okeru Nihon Bunka. Hohoron 0 motomeru tame no joshQ"

S*xf[:; - (Japanese Culture in East Asia. In-

troductory Chapter in Search of a Methodology). In Sekai no naka no Nihon

l. Nihon kenkyu no paradaimu: Nihongaku to Nihon kenkyu. s*

I. A - (Japan in the World l. The Para-

digm of Japanese Studies: Japanology and Japanese Studies), Kokusai Ni-

hon Bunka Kenkyii senta (International Research

Center for Japanese Studies), Kyoto 1989, pp. 197-198.

1990

32. Foreword and editorial note to Tonami Mamoru, The Shaolin Monastery

Stele on Mount Song, edited by Antonino Forte, Italian School of East Asian

Studies (Epigraphical Series 1), Kyoto 1990.

33. "The Relativity of the Concept of Orthodoxy in Chinese Buddhism:

Chih-sheng's Indictment of Shih-Ii and the Proscription of the Dharma Mir-

ror Sutra." In Chinese Buddhist Apocrypha, edited by Robert E. Buswell, Jr.,

University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu 1990, pp. 239-249.

34. "Francesco Carletti on Slavery and Oppression." In Giuliano Bertuccioli,

Travels to Real and Imaginary Lands. Two Lectures on East Asia, edited by

Antonino Forte, Italian School of East Asian Studies (Occasional Papers 2),

Kyoto 1990, pp. 59-80.

"On Carletti's Book with Particular Reference to his Chapter Conc!rning

Japan." In Giuliano Bertuccioli, Travels to Real and Imaginary Lands. Two

Lectures on East Asia, edited by Antonino Forte, Italian School of East Asian

Studies (Occasional Papers 2), Kyoto 1990, pp. 81-85.

36. "ltaria no futatsu no tOyo kenkyii kikan"

(Two Italian Research Institutions for Oriental Studies) . .{?T Y (Itali-

ana), 1990.1, pp. 29-36.

37. "Studying at the Jinbun-ken." Kyoto daigaku tsiishin .... (Kyo-

to University Newsletter), 11 (November 1990).

LIST OF PUBLICATIONS

23

1991

38. Foreword and Presentation to Ochiai Toshinori, The Manuscripts of

Nanatsu-dera. A Recently Discovered Treasure-House in Downtown Nagoya,

edited by Silvio Vita, Italian School of East Asian Studies (Occasional Pa-

pers 3), Kyoto 1991, pp. vii-ix, 1-3.

39. "My First Visit to Nanatsu-dera. Impromptu Notes and Impressions." In

Ochiai Toshinori, The Manuscripts of Nanatsu-dera. A Recently Discovered

Treasure-House in Downtown Nagoya, edited by Silvio Vita, Italian School

of East Asian Studies (Occasional Papers 3), Kyoto 1991, pp. 55-77.

1992

40. "Chinese State Monasteries in the Seventh and Eighth Centuries." In

Echo 6 Go-Tenjikkoku den kenkYLl (Huichao's Wang

Wu-Tianzhuguo zhuan Record of Travels in Five Indic Regions), edited by

Kuwayama ShOshin ,*=WJjE:i:f!, Kyoto daigaku Iinbun kagaku kenkyujo H:tIl

::k':A::x:f4,:1i3fJ'Em (Institute for Research in Humanities, Kyoto Universi-

ty), Kyoto 1992, pp. 213-258. (For a partial version in Japanese, see no. 54.)

41. "An Shigao and his Descendants." Bukkyo shigaku kenkYLl {?lJWl5t'.

(The Journal of the History of Buddhism), XXXV.l (July 1992), pp.

1-35.

42. "On the Subject of the Mingtang." Monumenta Serica, 40 (1992), pp. 387-

396. (Reflections on 1. Gernet's review of Mingtang and Buddhist Utopias in

the History of the Astronomical Clock, published in Toung Pao LXXVL4-5,

1990, pp. 337-340.)

43. "About Carletti's Attitude towards Slavery." East and West, 42.2-4 (De-

cember 1992), pp. 511-513.

44. Review: Nahal Tajadod, Mani Ie Bouddha de Lumiere. Catechisme mani-

chien chinois. Les editions du cerf, Paris 1990. Asian Folklore Studies, LI,2

(1992), pp. 367-369.

45. "Itaria TohOgaku kenkyujo" -{ l7 Y 7Jlt:1j':1i3fJ'Em (The Italian School of

East Asian Studies in Kyoto). TSLlshin (Circulaire de la Societe franco-

japonaise des etudes orientales), 14,15 (1992), pp. 26-27.

1993

46. "Again on the Subject of the Mingtang of the Empress Wu." Studies in

Central and East Asian Religions, 5/6 (1992-93), pp. 144-154.

24

ANTONINO FORTE (1940-2006)

47. Entries "An Shigao (fl. 148-170 circa)," "Bodhidharma (?-532?)," "Bud-

dha (566-486)," "Buddhismo," "Buddhismo cinese," "Buddhismo giap-

ponese," "Fazang (643-712)," "Nalanda," "Xuanzang (602?-664)," "Zen." In

Dizionario di storia e storiograjia, Edizioni .scolastiche Bruno Mondadori,

Milano 1993.

48. "A New Study on Manichaeism in Central Asia." Orientalistische Litera-

tur Zeitung 88.2 (Miirz/April1993), Nr. 1089, col. 117-124.

Review article of Moriyasu Takao Uiguru manikyo-shi no kenkya

':7-1 (A Study on the History of Uighur Manichaeism:

Research on Some Manichaean Materials and their Historical Background),

Osaka daigaku Bungaku-bu kiyo (Memoirs of the Fa-

culty of Letters Osaka University), Vols. XXXI and XXXII, August, 1991.

iii + 2 + 248 pages, 34 plates (of which the first 22 in colour), 23 figures, two

maps.

49. The Journal of Asian Studies, 52,1 (February 1993), pp. 107-'-108 (a com-

munication to the editor concerning the book Mingtang and Buddhist Uto-

pias in the History of the Astronomical Clock. The Tower, Statue and Armil-

lary Sphere Constructed by Empress Wu).

1994

50. "An Ancient Chinese Monastery Excavated in Kirgiziya." Central Asi-

atic Journal, 38.1 (1994), pp. 41-57.

51. (The Title of Grand Master in China and Japan). In

Hobogirin Dictionnaire encyclopedique du Bouddhisme d'apres

les sources chinoises et Japonaises, VII (1994), 1019-1034.

52. "Marginalia on the First International Symposium on Longmen Studies."

!$tudies in Central and East Asian Religions, 7 (1994), pp. 71-82.

53. "A Symposium on Longmen Studies, Luoyang, 1993." East and West,

44.2-4 (December 1994), pp. 507-516.

1995

54. "Shichi hachi seiki ni okeru Chugoku no kanji" 7 8i1!:{f,2.\;:;jOft0"POOO)

("Chinese State Monasteries in the Seventh and Eighth Centuries"), Ko-

dai bunka tl1-1(;:)(11::: (Cultura Antiqua), 47.7 (July 1995), pp. 380-390 (Eng-

lish summary, pp. 423-424). (A partial version in Japanese of no. 40.)

55. "Nanatsu-dera z6 Daijo Bishamon kudoku kyo 'ZenshO-bon' dai ni (hon-

koku)" (wtU) (,The Sujata Chapter,'

Second juan of the Satra of the Merits of of the Great Vehicle

LIST OF PUBLICATIONS

25

in the Nanatsu-dera [reproduced]). Setsuwa bungaku kenkya

(Studies on Legendary Literature), 30 (1995), pp. 121-131. In collaboration

with Toshinori. Ochiai and Silvio Vita.

56. Foreword to Inventaire sommaire des manuscrits et imp rimes ehinois de

la Bibliotheque Vatieane. A posthumous work by Paul Peliiot, edited by Taka-

ta Tokio, Italian School of East Asian Studies, Kyoto 1995, pp. VII-IX.

1996

57. Foreword to Paul Pelliot, L'inseription nestorienne de Si-ngan-j'ou, edited

with supplements by Antonino Forte, Italian School of East Asian Studies

(Epigraphical Series 2) and College de France, Kyoto and Paris 1996, pp.

vii-xii.

58. Avant-propos to Paul Pelliot, L'inseription nestorienne de Si-ngan-jou,

edited with supplements by Antonino Forte, Italian School of East Asian

Studies (Epigraphical Series 2) and College de France, Kyoto and Paris 1996,

pp. xiii-xix.

59. "The Edict of 638 Allowing the Diffusion of Christianity in China." In

Paul Pelliot, L'inscription nestorienne de Si-ngan-jou, edited with supple-

ments by Antonino Forte, Italian School of East Asian Studies (Epigraphical

Series 2) and College de France, Kyoto and Paris 1996, pp. 349-373.

60. "On the So-called Abraham from Persia. A Case of Mistaken Identity."

In Paul Pelliot, L'inseription nestorienne de Si-ngan-jou, edited with supple-

ments by Antonino Forte, Italian School of East Asian Studies (Epigraphical

Series 2) and College deFrance, Kyoto and Paris 1996, pp. 375-428.

61. "The Chongfu-si in Chang'an. A Neglected Buddhist Monastery

and Nestorianism." In Paul Pelliot, L'inscription nestorienne de Si-ngan-jou,

edited with supplemerits by Antonino Forte, Italian School of East Asian

Studies (Epigraphical Series 2) and College de France, Kyoto and Paris 1996,

pp. 429-472.

62. "A Literary Model for Adam. The Dhfita Monastery Inscription." In Paul

Pelliot, L'inscription nestorienne de Si-ngan-jou, edited with supplements by

Antonino Forte, Italian School of East Asian Studies (Epigraphical Series 2)

and College de France, Kyoto and Paris 1996, pp. 473-487.

63. "Additional Remarks" to Paul Pelliot, L'inscription nestorienne de Si-

ngan-j'ou, edited with supplements by Antonino Forte, Italian School of East

Asian Studies (Epigraphical Series 2) and College de France, Kyoto and

Paris 1996, pp. 489-495.

26

ANTONINO FORTE (1940-2006)

64. "Kuwabara's misleading thesis on Bukhara and the family name An "ii."

Journal of the American Oriental Society, 116.4 (1996), pp: 645-652.

65. "On the Identity of Aluohan (616-710), a Persian Aristocrat at the Chi-

nese Court." In La Persia e l'Asia Centrale. Da Alessandro al X secolo, Ac-

cademia Nazionale dei Lincei, Roma 1996, pp. 187-197.

66. "The Origins and Role of the Great Fengxian Monastery at

Longmen." Annali dell'Istituto Orientale di Napoli, 56.3 (1996), pp. 365-

387.

1997

67. "Longmen Da Fengxian si de qiyuan ji diwei"

ill ("On the Beginning and Status of Big Fengxian Temple at the Longmen

Grotto"), Zhongyuan wenwu rpJJl'i:JtIfto (Cultural Relics of Central China),

1997.2, pp. 83-92. (A Chinese translation [unchecked by the author] of a

preliminary version of no. 66. Published under the author's Chinese name

Fu Andun

68. "Fazang's Letter to Uisang. Critical Edition and Annotated Translation."

In Kegongaku ronshu (Collected Essays on Avatal1lsaka Stud-

ies), edited by the Kamata Shigeo hakushi koki kinenkai

Daizo shupp an Tokyo 1997, pp.109-129.

1998

67. "Some Considerations on the Historical Value of the Great Zhou Cata-

logue." In Chiigoku Nihon kyoten shOsho mokuroku rpOO

(Catalogues of Scriptures and their Commentaries in China and Japan), 6th

volume of the Nanatsudera koitsu kyoten kenkyii sosho

(The Long Hidden Scriptures of Nanatsu-dera, Research Series), edited by

Makita Tairyo and Ochiai Toshinori Daito shuppansha

*J![tI:lJjR1lf, Tokyo 1998, pp. 21-34 of the German and English part of the

book.

68. "Da Shu kantei shukyo mokuroku juichi" (The

Eleven Fascicle of the Da Zhou kanding mulu). In Chugoku Nihon kyoten

shOsho mokuroku rpOO of Scriptures and

their Commentaries in China and Japan), 6th volume of the Nanatsudera

koitsu kyoten kenkyu sosho (The Long Hidden Scrip-

tures of Nanatsu-dera, Research Series), edited by Makita Tairyo

and Ochiai Toshinori Daito shuppansha **tI:lJjR1lf, Tokyo 1998,

pp.3-58.

LIST OF PUBLICATIONS

27

69. "The Maitreyist Hl1aiyi (d. 695) and Taoism." Tang yanjiu (Jour-

nal o/Tang Studies), IV (1998), pp. 15-29.

70. "Wu Zhao de mingtang yu (The

Mingtang of Wu Zhao and the Astronomical Clock). In Wu Zetian yanjiu

lunwenji (Collected Research Papers on Wu Zetian), ed-

ited by Zhao Wenrun Li Yuming Shanxi guji chubanshe

Taiyuan 1998, pp. 140-147. (A Chinese translation [un-

checked by the author] of the concluding part (pp. 253-260) of Mintang and

Buddhist Utopias in the History o/the Astronomical Clock (see Books, no. 3).

Published under the author's Chinese name Fu Andun

71. Review: Silvio A. Bedini, The trail 0/ time. Time measurement with in-

cense in East Asia. Shih-chien ti tsu-chi, Cambridge University Press, Cam-

bridge, 1994. xvii + 342 pp. Archives Internationales d'Histoire des Sciences,

vol. 48 no. 140 (1998), pp. 225-226.

1999

72. "The Sabao iiiJf Question." The Silk Roads Nara International Sympo-

sium '97. Vol. 4: The Silk Road of Sanzo-Hoshi Xuanzhuang: The Climate

and His Foot-Steps. Research Center for Silk Roadology, Nara, March 1999,

pp.80-106.

73. "Sappo mondai" (The Sabao Question). Shirukurodo Nara

kokusai shinpojiumu kirokushu Vol. 4: Sanzo hoshi Genjo no Shirukurodo:

Fudo to ashiato p- 4:

p- Silk Roads Nara International Sympo-

sium Vol. 4: The Silk Road of Trepitaka Master of the Law Xuanzang: Natu-

ral Features and [Xuanzang's] Footsteps). Shirukurodogaku kenkyu sentli

)v::7 p- (Research Center for Silk Roadology), Nara 1999,

pp. 102-124. (Japanese version of no. 72.)

74. "Francesco Carletti sulla schiavitu e l'oppressione." Strumenti critici

XVI.2 (maggio 1999), pp. 1-21. (Italian revised version of the article "Fran-

cesco Carletti on Slavery and Oppression" published in 1990).

75. "The Maitreyist Huaiyi (d. 695) and Taoism. Additions and Corrections."

Tang yanjiu (Journal o/Tang Studies), V (1999), pp. 35-38. (A Chi-

nese summary of no. 69, as augmented and emended in no. 75, is on pp.

38-40 of the same journal: "Milejiao zhe Huaiyi [695 nian zu] yu daojiao

[tiyao]"

76. "The Clock and the Perfect Society." Kyoto Journal, 42 (1999), pp. 28-

31.

28

ANTONINO FORTE (1940--'2006)

2000

77. "Iranians in China. Buddhism, Zoroastrianism, and Bureaus of Com-

merce." Cahiers 11 (1999-2000), pp. 277-290. (English ver-

sion of no. 78.)

78. "Iraniens en Chine. Bouddhisme, mazdeisme, bureaux de commerce."

In La Serinde, terre d'echanges. Art, religion, commerce, du Ier au Xe siecle.

Actes du colloque international Galeries nationales du Grand Palais 13-14-

15 fevrier 1996, edited by Jean-Pierre Drege, La Documentation fran<;:aise,

Paris 2000, pp. 181-190.

79. ''Additions and Corrections to A Jewel in Indra's Net." Cahiers d'Extreme-

Asie, 11 (1999-2000), pp. 345-348.

2001

80. "The Five Kings of India and the King of Kucha who According to the

Chinese Sources Went to Luoyang in 692." In Le parole e i marmi. Studi in

onore di Raniero Gnoli nel suo 70 compleanno, edited by Raffaele Torella,

Serie Orientale Roma XCII, Istituo Italiano per l'Africa e l'Oriente, Roma

2001, pp. 261-283.

81. "Fazang e Sakyamitra (fl. 664-670), un medico singalese del settirno

secolo alIa corte cinese." In Filosofia, storiografia, letteratura. Studi in onore

di Mario Agrimi, edited by Bernardo Razzotti, Editrice Itinerari, Lanciano,

2001, pp. 925-962. (Italian version of no. 82.)

2002

82. "Fazang and Sakyamitra, a Seventh-century Singhalese Alchemist at the

Chinese Court." In Zhong shiji yiqian de diyu wenhua, zongjiao yu yishu

(Regional Culture, Religion, and Arts

before the Seventh Century). Zhongyang yanjiuyuan Disanjie guoji hanxue

huiyi lunwenji, lishi (Pa-

pers from the Third International Conference on Sino logy, History Section),

edited by I-tien Hsing (Xing Yitian) Zhongyang yanjiuyuan lishi

yuyan yanjiusuo (Institute of History and Phi-

lology, Academia Sinica), Taipei 2002, pp. 369-419.

83. "The South Indian Monk Bodhiruci (d. 727). Biographical Evidence." In

A Life Journey to the East. Sinological Studies in Memory of Giuliano Ber-

tuccioli (1923-2001), edited by Antonino Forte and Federico Masini, Scuola

Itahana di Studi sull'Asia Orientale (Essays 2), Kyoto 2002, pp. 77-116.

LIST OF PUBLICATIONS

29

84. "The Chinese Title of the Manichaean Treatise from Dunhuang." An-

nali dell'Universita degli studi di Napoli "L'Orientale", 62.1-4 (2002), pp.

229-243. (English modified version of no. 87.)

2003

85. "Daisojo ::k{)!fj]E" (Grand Rector of the Sa:rp.gha). Hobi5girin

Dictionnaire encyclopedique du Bouddhisme d'apres les sources chinoises et

Japonaises, VIII (2003), pp. 1043-1070.

86. "Daitoku ::k1ffJJ" (The Title of Great-Virtue). Hobi5girin Dic-

tionnaire encyclopedique du Bouddhisme d'apres les sources chinoises et

Japonaises, VIII (2003), pp. 1071-1085.

87. "II titolo cinese del Traite manicheen." In Turcica et Islamica. Studi in

memoria di Aldo Gallotta (Series Minor 64), edited by Ugo Marazzi, Univer-

sita degli Studi di Napoli "L'Orientale," Napoli, vol. I, pp. 215-243.

88. "Suowei Bosi 'Yabolahan.' Yili cuowu de biding." -

("On the So-called Abraham from Persia. A Case of Mis-

taken Identity"). In Tangdai jingjiao zai yanjiu (New Re-

flections on Nestorianism of the Tang Dynasty), edited by Lin Wushu

:7,*, Zhongguo shehui kexue chubanshe r:p (China Academy

of Science Press), Beijing 2003, pp. 231-267. (An abridged Chinese transla-

tion [unchecked by the author] by Huang Lanlan of no. 60, published

under the author's Chinese name Fu Andun

89. "La Scuola di Studi sull'Asia Orientale di Kyoto. Note sparse." In Italia-

Giappone 450 anni, edited by Adolfo Tamburello, Istituto Italiano per l'Africa

e l'Oriente, Roma, and Universita degli Studi di Napoli "L'Orientale," Napoli

2003,pp.712-723.

90. "On the Origin of the Purple in China." In Buddhist Asia 1.

Papers from the First Conference of Buddhist Studies Held in Naples in May

2001, edited by Giovanni Verardi and Silvio Vita, Italian School of East

Asian Studies, Kyoto 2003, pp. 145-166.

91. "L'intervista a Buddhapalita nel 677 0 all'inizio del 678." In Studi in on-

ore di Umberto Scerrato per il suo settantacinquesimo compleanno, edited

by Maria Vittoria Fontana and Bruno Genito, Universita degli studi di Napoli

"L'Orientale" and Istituto Italiano per l'Africa e l'Oriente, Napoli 2003, pp.

369-384.

92. Review: Maurizio Scarpari, Ancient China: Chinese Civilization from ist

Origins to the Tang Dynasty. Barnes and Noble Books, 2000. Journal of the

American Oriental Society, 123.4 (2003), pp. 851-860.

30

ANTONINO FORTE (1940-2006)

2004

93. "Remarks on Chinese Sources on Diva:kara (613-688)." In Chugoku

shukyo bunken kenkyu kokusai shinpojiumu hokokusho

(Report of the International Symposium: Researches

on Religions in Chinese Script), Kyoto daigaku Jinbun kagaku kerikyiijo *

(Institute for Research in Humanities, Kyoto Univer-

sity), Kyoto, December 2004, pp. 75-82.

2005

94. "Cenni storici e re1azioni estere, religioni straniere, scienze." In Tang.

Arte e cultura in Cina prima dell'anno Mille, edited by Lucia Caterina and

Giovanni Verardi, Electa, Napoli 2005, pp. 25-37.

95. "II monaco indiano Bodhiruci (m. in Cina nel 727). Note biografiche." In

Studi in onore di Luigi Po lese Remaggi, edited by Giorgio Amitrano, Lucia

Caterina, Giuseppe De Marco, Universita degli Studi di Napoli "L'Orientale"

(Series Minor LXIX), Napoli 2005, pp. 199-242.

2006

96. "Buddhismus und Politik - Die Kaiserin Wu Zetian und der Famen-Tem-

pel." In Xi'an. Kaiserliche Macht im Jenseits. Grabfunde und Tempelschiitze

aus Chinas alter Hauptstadt (Catalogue of the exhibition held at the Kunst-

und Ausstellungshalle der Bundesrepublik Deutschland in Bonn, April 21

- July 23, 2006), Philipp von Zabern, Mainz 2006,pp. 109-119.

97. "Brief Notes on the Kashmiri Text of the Dhiirm;! Sutra of AvalokiteSvara

of the Unfailing Rope Introduced to China by Manicintana (d. 721)." In Tang-

dai fojiao yu fojiao yishu (Tang Buddhism and Bud-

dhist Art) edited by Kathy Cheng-mei Ku (Gu Zhengmei) Chuefeng

fojiao yishu jijinhui (Chuefeng Buddhist Art and Culture

Foundation), Taiwan 2006, pp. 13-28. (A revised version of no. 18.)

2007

98. "Jibakara ni kan suru kango shiryo" (Re-

marks on Chinese Sources on Diva:kara). In Chugoku shukyo bunken kenkyu

(Researches on Religions in Chinese Script), edited by

Kyoto daigaku Jinbun kagaku kenkyiijo (Institute

for Research in Humanities, Kyoto University), Rinsen shoten I:lii;) 11:J:J;5,

Kyoto 2007, pp. 109-117.

LIST OF PUBLICATIONS

31

Listed as "forthcoming articles" in 2006

i. Entries "Daiunky5 "Daiunji and "An Seik5 in

Chilgoku bunkashi daijiten r:pOOJt1t:.se:kI'i"fA (provisional title), to be pub-

lished by Taishukan, Tokyo.

2. "The So-called Buddhapalita Chinese Version of the vi-

jaya dhiiralJfsiltra and its preface." In Kuo Liying (ed.), volume in honour of

Makita Tairy5.

3. "Scrittura e ideologia in Cina. Note sui caratteri particolari del periodo

689-705." A paper presented at the .conference "II testo, il supporto e la fun-

zione." Cortona and Viterbo, 13-15 Novembre 2003.

4. "On the Origins of the Great Fuxian Monastery in Luoyang."

Rome, July 24, 2009

THE FORMULATION OF INTRODUCTORY TOPICS AND

THE WRITING OF EXEGESIS IN CHINESE BUDDHISM

1

TAOJIN

As a guide to the interpretation of sutras, introductions in Chinese

Buddhist commentaries almost always present a wide range of top-

ics that allow commentators to survey the texts they comment upon

from various different perspectives. The formulation of these intro-

ductory topics varies with commentators and, in many cases, also

with commentaries of the same commentator. While, for example,

Zhiyi (538-597) adheres steadfastly to his famous model of "five

aspects of profound meaning" (wuchong xuanyi), regarding the

"title" (ming) of the work, the "essence" (ti), "central tenet" (zong)

and "function" (yang) of the religious truth taught in it, and the

"characteristics" (xiang) that set one sutra apart from another on

the basis of these four aspects,2 his slightly younger contemporary

1 This paper is adapted from a chapter of my 2008 dissertation, "Through

the Lens of Interpreters: the Awakening of Faith in Mahayana in Its Classi-

cal Re-presentations;" an earlier version of this chapter was presented in the

2005 Annual Meeting of American Academy of Religion. I want to thank the

anonymous reviewer of the JIABS for his or her careful and insightful com-

ments and suggestions.

2 For a discussion of the structural relationship of these "five aspects," see

below, section three: Elaboration of teaching: from essence to its manifesta-

tions. The topic of "characteristics" is designed to differentiate a particular

sutra from others, or to determine its position in a tradition by comparing

its "characteristics" with those of others. A commentary of the Sutra of the

benevolent kings (Renwanghuguoboruojing shu) thus spells out this sense of

"differentiation" as follows: '''Teaching' (jiao) refers to the words with which

sages edify the people, and 'characteristics' differentiate similarities from

differences (in various such teachings)" (T33n1705p255b9). It is perhaps for

this sense of "differentiation" that the topic of "characteristics" is often used

Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies

Volume 30 Number 1-2 2007 (2009) pp. 33-79

34

TAOJIN

Jizang (549-623) appears to be much less focused and organized

in his exegetical attention - indeed, he has never really settled on

any set of introductory topics, sometimes even allowing the list of

his inquiries to be rampantly open,3 and occasionally also find-

ing it convenient to borrow Zhiyi's "five aspects.'>! Such examples

abound in Chinese Buddhist commentaries and, together, they am-

ply demonstrate the variation in the formulation of introductory

topics in the writing of exegesis in Chinese Buddhism.

This variation draws our attention to the breadth and depth of

commentators' introductory surveys, for it asks us to think about

what questions different commentators raise in their introductions,

and how they in their respective ways understand, organize and

present these questions - with the former reflecting the breadth of a

survey and the latter, the depth. Put in other words, such a variation

directs our attention, not to what is said in commentaries, but to

how it is said, or, using the words of this article, not to the content

of exegesis, but to the writing of exegesis.

This attention to the writing of exegesis is, apparently, not

something new. In his magnum opus on the history of Chinese

Buddhism, Tang Yongtong touches upon the issues of origination

and methods of the Chinese Buddhist exegesis;5 Mou Runsun ex-

plores the relationship between siitra lectures and commentaries in

his 1959 comparative study of the Confucian and Buddhist exege-

, ~ i s from, particularly, the perspective of rituals performed during

to discuss the practice of doctrinal classification (panjiao).

3 For example, he has ten topics in Milejing youyi (T38n1771), and these

ten still do not seem to have exhausted all that he wants to ask about that sutra,

because his tenth topic "clarification of miscellaneous issues" (zaliaojian) is

made, apparently, to include more or "miscellaneous issues."

4 See, for example, the introduction of his Renwangboruojing shu,

T33n1707.

5 Tang, Hanwei liangjin nanbeichao fojiaoshi, pp. 114-20 & 546-52.

INTRODUCTORY TOPICS AND EXEGESIS IN CHINESE BUDDHISM 35

those lectures;6 OchO Enichi's 1979. "Shakuky6shik6" presents a

comprehensive inquiry into the evolution of the Chinese Buddhist

exegesis;7 the conference on and the subsequent publication of Bud-

dhist Hermenutics in 1988 look at the "principles for the retrieval of

meaning," an indispensable element in the interpretation of sutras;8

and, in his 1999 study of Chinese prajiiii interpretation, Alexander

Mayer assigns three levels of significance to Buddhist interpreta-

tion, namely, exposition, exegesis, and hermeneutics.

9

This list has

been continuously growing in recent decades.lO

While scholars have approached the writing of exegesis from all

these various perspectives, the formulation of introductory topics

has remained largely an unexplored subject. This subject entails

such questions as: What questions are generally asked to introduce

a sutra? How are these questions related to each other or, in other

words, how do commentators categorize their inquiries in different

ways? And, more importantly, how do the asking and re-asking

of these questions expand and deepen the exegetical inquiry into

sutras and, in that sense, contribute to the development in the writ-

ing of exegesis in Chinese Buddhism? This article thus aims to ad-

dress these previously unanswered questions by focusing its atten-

tion on the formulation of introductory topics in Chinese Buddhist

commentaries.

6 Mou, "Lun rushi liangjia zhijiangjing yu yishu," pp. 353-415.

7 OchO, "Shakukyoshiko," pp. 165-206.

8 Lopez, ed., Buddhist Hermeneutics, p. 1.

9 Mayer, "The Vajracchedika-sutra and the Chinese Prajfiil Interpreta-

tion."

10 Continuously broadened and deepened in recent years, the scholarly at-

tention to the writing of exegesis has been mostly focused on a number of ma-

jor topics, such as the practice of "matching of meaning" (geyi) in the initial

stage of Buddhism's introduction into China, satra lectures, sutra transla-

tion, relationship among Confucian, Daoist and Buddhist exegesis, and re-

lationship between Buddhist exegesis and popular literature, and between

Buddhist exegesis and literary theory.

36

TAOJIN

While it is difficult to give a conclusive list of all introductory

topics actually used in Chinese Buddhist commentaries, several

themes in the introductory inquiries appear to be more recurrent

than others. Even it is difficult to reproduce the exact course in

which these themes evolved, such a course can be seen roughly

as characterized by a movement of commentators' attention from

brief thematic discussions, which rely heavily on the explanation of

title, to elaborations of the introductory survey from v ~ r i o u s per-

spectives. Hence the following list of seven themes, on the basis of

which the formulation of introductory topics is to be treated below

in seven sections:

ll

1. title

2. introductory summary

3. elaboration of teaching

4. arising of teaching

5. central tenet

6. medium of truth

7. classification of teachings

The first two revolve around title and its role in the writing of an

introduction, and the remaining five elaborate upon the process of

introductory survey, with the third as a general discussion and the

last four as discussions of a few specific themes frequently exam-

ined in that elaboration. As a general pattern of discussion, each

of the seven sections is engaged primarily with two tasks, i.e., a

,:general overview of a particular theme and a look at the introduc-

II Well-known as they may be, these seven themes have apparently not

exhausted all questions commentators have asked of their siitras. They also

look, for example, at the audience of teaching, among many others, and this

theme gives rise to such introductory topics as Jizang's "number of people at-

tending (Buddha'S) assembly (of Dharma)" (huiren duoshao, T38nl771) and

"believers and followers" (tuzhong, T35n1731 and T38n1780), Won'chuk's

"sentient beings (for whom) the teaching is intended" (suowei youqing,

T33n1708), Wonhyo's "categorization of people" (juren fenbie, T37n1747),

Kuiji's "clarification of the time (in which) and the faculties (for which) the

teaching (is given)" (bianjiao shiji, T43n1830), and many of Fazang's "facul-

ties (for which) the teaching is intended" (jiaosuo beiji).

INTRODUCTORY TOPICS AND EXEGESIS IN CHINESE BUDDHISM 37

tory topics formulated on that basis, though not necessarily always

distinctly in such an order.

1. Explanation of work title

To most Chinese Buddhist exegetes, explanation of title is perhaps

the most natural and most logical first step in the writing of intro-

duction. Located in the beginning of a text, title is naturally the

first thing that catches a commentator's attention, and, perceived

as embodying the central tenet of a sutra,12 it is treated, logically,

as the most ideal platform for a thematic survey of that sutra. It is

probably for this reason that the Chinese Buddhist exegetes always

start their exegesis with an effort to kai-ti, or to "layout the subject

matter (through the explanation of title),"13 and it is for this same

reason that almost all commentaries contain a section on title and,

in many cases, such a section begins a commentary. In fact, the

12 For example, in his Wuliangshoujing yishu, Huiyuan lists ten types of

title, five of which, i.e., 1", 7th, 8

th

, 9

t

h, and 10

th

, are represented as embody-

ing central tenet, either completely or partially

Even when it does not fall into one of these five categories, commentators

still tend to use title to discuss central tenet in their introductions. For an

example see Wonhyo's "main ideas" (dayi) in his

Mileshangshengjing zongyao, where the "main ideas" of teaching are sum-

marized through a discussion of the future Buddha Maitreya (i.e., "Mile" in

Chinese), after whom the satra is named.

13 The word ti in kai-ti refers to "subject matter" instead of its more obvi-

ous meaning of "title," although the word itself can be understood in both

ways. Thus, to kai (i.e., open) ti is to "layout the subject matter." However,

if we take a look at the content of kai-ti-xu, (i.e., introduction laying out the

subject matter), such as those in Jizang (ex., T34nl722p633b12) and Kuiji

(ex., T33n1695p26a19), it is quite clear that the laying out of ti as subject mat-

ter relies heavily on the explanation of ti as title. In that sense, it would be not

unreasonable to suggest that, in the context of Chinese Buddhist exegesis,

when a commentator sets out to kai-ti, he thinks not only of the "subject mat-

ter," but also of the "title" that embodies such a "subject matter."

38

TAOJIN

introductory sections in many early are devoted al-

most entirely to the explanation of title.

14

The interest in title is expressed in two different perceptions

about its role in the writing of commentaries. On the one hand,

believed to embody central tenet, title is sometimes treated as a

means of exegesis, i.e., title is sometimes used to summarize and

bring out the central tenet of a sutra as a way to begin a com-

mentary.lS On the other hand, however, the increasing attention to

title itself also allows it to be treated as an end of exegesis, i.e., an

introductory topic in its own right, which can be examined for its

various aspects, such as those philological, textual, biographical,16

typological and etc. A typological analysis of title by Huiyuan is

given below as an illustration:

The title of a sutra (is formed) differently, and (its formation) contains

many varieties. Some (are formed to) reflect the Dharma (ofthe sutra);

some (are formed) from the perspective of the person (who teaches the

Dharma); some, in accordance with the event (in which the Dharma is

taught); some, to follow the metaphor (of the Dharma); some, to dwell

upon the person and the Dharma; some, on (both) the Dharma and the

metaphor; some, on (both) the event and the Dharma. Such examples

are simply innumerableP

14 See, for example, the introductions in Dao'an's Renbenyushengjing zhu

(T33n1693), Sengzhao's Zhu weimojiejing (T38nl775), and the ten commen-

taries compiled in the Dapanniepanjing jijie (The Collected explanations of

the NirvalJasatra, T37n1763; hereafter referred to as the "Collected explana-

tions" for the sake of convenience).

15 This role will be discussed further in section two: Summary of teaching

as pre-introduction.

16 Because the discussion of title sometimes includes a discussion of au-

thor; see also the discussion of the close association between "intention,"

"author" and "title" (as well as the notes thereof) in section four: Accounting

for the arising of teaching: intention, conditions and transmission.

17 T37n1764p613b15-b17.

INTRODUCTORY TOPICS AND EXEGESIS IN CHINESE BUDDHISM 39

The interest in title finds its most sophisticated expression in Zhiyi's

commentaries, where the two perceptions of its role fuse and the

examination Of title becomes extremely complex. On the one hand,

Zhiyi sometimes devotes an entire commentary to the expJ.anation