Professional Documents

Culture Documents

City Limits Magazine, January 1991 Issue

Uploaded by

City Limits (New York)Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

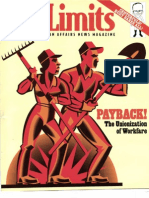

City Limits Magazine, January 1991 Issue

Uploaded by

City Limits (New York)Copyright:

Available Formats

January 1991 New York's Community Affairs News Magazine $2.

00

M E L R O S E C O M M O N S Q U E S T I O N S 0 S T A R O F T H E S E A

W H O I S R U N N I N G T H E W E L F A R E H O T E L S ?

City Lilftits

Volume XVI Number 1

City Limits is published ten times per year.

monthly except double issues in June/July

and August/September. by the City Limits

Community Information Service. Inc . a non-

profit organization devoted to disseminating

information concerning neighborhood

revitalization.

Sponsors

Association for Neighborhood and

Housing Development. Inc.

Community Service Society of New York

New York Urban Coalition

Pratt Institute Center for Community and

Environmental Development

Urban Homesteading Assistance Board

Board of Directors *

Eddie Bautista. NYLPIICharter Rights

Project

Beverly Cheuvront. NYC Department of

Employment

Mary Martinez. Montefiore Hospital

Rebecca Reich. Turf Companies

Andrew Reicher. UHAB

Tom Robbi\ls. Journalist

Jay Small. ANHD

Walter Stafford. New York University

Pete Williams. Center for Law and

Social Justice

Affiliations for identification only.

Subscription rates are: for individuals and

community groups. $15/0ne Year. $25/Two

Years; for businesses. foundations . banks.

government agencies and libraries. ~ 3 5 / 0 n e

Year. $50/Two Years. Low income. unem-

ployed. $10/0ne Year.

City Limits welcomes comments and article

contributions. Please include a stamped. self-

addressed envelope for return manuscripts.

Material in City Limits does not necessarily

reflect the opinion of the sponsoring organiza-

tions. Send correspondence to: CITY LIMITS.

40 Prince St . New York. NY 10012.

Second class postage paid

New York. NY 10001

City Limits (ISSN 0199-0330)

(212) 925-9820

FAX (212) 966-3407

Editor: Doug Turetsky

Associate Editor: Lisa Glazer

Contributing Editors: Mary Keefe.

Peter Marcuse. Margaret Mittelbach

Production: Chip Cliffe

Photographers: Adam Anik.

Andrew Lichtenstein. Franklin Kearney

Intern: Elizabeth von Nardroff

Copyright 1991. All Rights Reserved. No

portion or portions of this journal may be

reprinted without the express permission of

the publishers.

City Limits is indexed in the Alternative Press

Index and the Avery Index to Architectural

Periodicals and is available on microfilm from

University Microfilms International . Ann

Arbor. MI48106.

Cover photograph of the World Trade Center by the

Port Authority of New York and New Jersey

2/JANUARY 1991/CITY UMITS

Bring Back the Public

O

ver the past 25 years, quasi-government agencies known as public

authorities have become important forces in the city's political

landscape. From just a handful of public authorities like the Port

Authority of New York and New Jersey (which is examined in this

issue) and the Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority, the number has

grown to some 30 such agencies.

Public authorities operate our trains, sponsor huge development

projects, build schools, provide financing for housing, among other

activities. And they do much of it with their own money, raised through

the sale of bonds.

This sounds fairly benign, until one realizes that public authorities

carryon their activities with little public oversight or legislative review.

That's why public authorities have become increasingly popular with

mayors and governors, who can use these agencies to push forward

controversial initiatives without the administrative or financial ac-

countability required of typical government departments. (Some public

authorities have become virtual fiefdoms, beyond the control of even the

executive branch. Felix Rohatyn's Municipal Assistance Corporation,

which sparred frequently with Mayor Ed Koch, is a recent example.)

Activists and legislators have viewed public authorities with growing

suspicion. But now a new trend is developing that may well make public

authorities even more inaccessible: they're taking on projects in consort.

The Hunters Point development in Queens is the work of three such

agencies, the Port Authority, the Urban Development Corporation (UDC)

and the Public Development Corporation (PDC). (PDC is technically not

a public authority but is a quasi-government entity with similar powers.)

Likewise, the redevelopment of piers 1 to 5 in Brooklyn Heights is being

undertaken by these three entities. The 42nd Street Project is the handi-

work of a subsidiary of UDC and PDC.

Such combinations of semi-public agencies may well get more com-

mon as the city's and state's financial positions worsen. Legislators,

activists and other government watchers should be wary. It's time to

reemphasize the idea of the public in public authorities.

* * *

There's really only one way to describe the Daily News' use of the

homeless to help break the newspaper's strike: repugnant. By enlisting

the homeless as hawkers, the newspaper's management has found a way

of getting the scab-produced paper on the streets at relatively little cost.

It's hard to blame the homeless for accepting the work. For those tossed

to the bottom of society's heap, any shot at making a day's wage seems too

good to turn down. Solidarity with the strikers is far easier for those with

a full belly and a home.

But there is simply no excuse for the Daily News' cynical ploy.

Whether the strike is settled or the paper folds the homeless hawkers will

undoubtedly be cast off, the few bucks they earned just a memory. James

Hoge should be ashamed.

* * *

City Limits has lost another member of its board of directors to public

office. Richard Rivera was resoundingly-and deservedly-elected as a

Civil Court judge from Brooklyn. Our loss is the judiciary's gain. 0

FEATURE

For Whom Does the Port Authority Toll? 12

Few New Yorkers know much about this multi-billion

dollar agency. It's time they did.

DEPARlMENlS

Editorial

Bring Back the Public .... ....... .............. ..... ..... .... ...... . 2

Briefs

Homeless Again? ........ ... ..... ... ......... .............. ....... ..... 4

ATURA Renewal .................. ....................... ............. 4

AIDS Housing Money .... .......... ......... ................. ...... 5

Profile

Shining Star .... ..... ..... .... ..... ....... ....... ............... ... .. .... 6

Pipeline

Return Offenders ........................... ...... ..... ........ ..... ... 8

Commons Concerns ........ ... ..... ..... ...... ... ....... ... ....... 18

City View

For Nonprofits, Less Money

Means More Organizing ... .. ... .......... ............... ... .. .. 20

Review

Of Homes and Cadillacs ............ ............. ............... 21

Shining Star/Page 6

Return/Page 8

Port Authority/Page 12

CITY UMITS/JANUARY 1991/3

HOMELESS AGAIN?

When Barbara Young and

Joan Jacobs and their 16

children and grandchildren

moved out of the shelter system

and into a two-family Queens

home in 1988, they thought

their troubles were over. But

now they're on the brink of a

return to homelessness.

Queens landlord Marcus

Habeeb received $43,000 from

the city's Emergency Assistance

Rehousing Program (EARP) for

agreeing to rent the house to the

families for 32 months at 106-

26 156th Street in Jamaica. He

received half the payment when

the families first moved in and

the final installment in Septem-

ber, 1989. Unbeknownst to the

city, Habeeb had stopped

making mortgage payments and

foreclosure proceedings started

on the building in August,

federal Section 8 housing

subsidies with the money given

to landlords, and the amount is

usually enough to encourage

landlords to keep housing

families once the 32-month

agreement is completed.

However, an earlier version of

the program that didn't include

the Section 8 tie-in led many

landlords to try and get rid of

families after the 32 months

were over. "We continue to see

clients at imminent risk of re-

entering the shelter system,"

says Steve Banks, the supervis-

ing attorney for the legal Aid

Society's Homeless Family

Rights Project. Banks says that

there are "at least several

hundred families" still at risk of

eviction because their landlords

are operating within the original

version of EARP.

1988. Habee6 has skipped

town, the property has changed

hands and the two families are

now fighting eviction.

"It's appalling," says

Randolph Petsche, an attorney

from Queens legal Services

who is representing the families.

"It is not a matter of pointing a

finger at anyone individual in

the city, but there must be some

way of safeguarding against

this."

At 1 06-26 156th Street, the

problems appear to stretch be-

yond the former landlord and

city policies. The current pro-

perty owner, Hertzl Moezinia of

.......... . __ the Five Boro Development

Corporation, purchased the

building from the First National

Mortgage Company in Garden

City, wnich foreclosed on the

home when Habeeb stopped

making mortgage payments.

First National is being sued for

fraud in connection to a number

of its properties by the Federal

Home loon Mortgage Corp?ra-

tion (Freddie Mac). A Freddie

Mac spokesperson refused to

provide any additional details.

D M.-yKeef.

Michael Handy, the director

of the EARP program, which is

run by the city's Human

Resources Administration, says

that his office will try to find

BIc:k to Sq ..... One?: Joan Jacobs is facing a possible return to

homelessness.

apartments for the women but

cannot .9uarantee that they will

not be forced to return to the

shelter system. He adds that city

did check some financial

records before giving EARP

money but had no way of

knowing about Habeeb's

mortgage problems. And he

notes that the city's law

department is now trying to

track down Habeeb and hold

him accountable.

This is not the first time that

homeless families receiving

housing through the EARP

program have faced the threat

of a return to the shelter system.

Under the current version of the

program, the city includes

In 1000.

13

12

11

10

NYC Homeless Family Count

(In Shelter System)

11,976 11,842 *

7

4

2

1

o

o November 30, 1989

NoenIber 30, 1990

5,063

* Includes adults in special residences

4/JANUARY 1991/CITY UMITS

T_

CIoIIII ...

T_

.........

Soun;e: NYC Human Resoun;es Administration

ATURA RENEWAL?

The controversial

Terminal Urban Renewal Area

project in Brooklyn may be

having financing difficulties that

could force the project back to

the drawing bOOrd, according

to attorneys and community

leaders challenging the project.

Rose Associates, who was

named developer of the city-

sponsored project in 1987, is

seeking to find equity partners

for the project or pull out of it all

together, according to several

sources. And this month there

will be a hearing on a lawsuit

that seeks to block a $10.8

million federal Urban Develop-

ment Action Grant (UDAG) to

,

.

the project.

The $530 million project,

adjacent to the Long Island

Railroad terminal at Atlantic

and Flatbush Avenues, is slated

to include three million square

feet of office space, 400,000

square feet of retail space, two

parking garages, 10 movie

theaters and 643 condomini-

ums. It was approved by the

Board of Estimate in October,

1986, and was immediately

challenged by community

groups on the grounds that the

project will add to local air

pallution and could displace

many lower income residents

near the development.

Community leaders say Rose

Associates wants to assign its

interest in the proiect to Forest

City/Ratner, developers of the

downtown Metrotech project,

because it has not been able to

find an anchor tenant for the

office space and cannot obtain

bank financing.

"If Rose is out of the picture,

it makes a whole new 0011-

game," says Ted Glick, co-chair

of the ATURA Coalition, which

is fighting the project. "Forest

City/Ratner is not committed to

the Rose plan," he says, and

may be willing to work with

community groups to redesign

the project. 'With a new

developer, there's an oppartu-

nity to bring up issues [we're

concerned about] and reach a

settlement," adds Tom Rothchild,

attorney for a block association

that filed suit against the project.

A Forest City spokeswoman

would neither confirm nor deny

their interest in the project.

Rose's attorneys, the firm of

Kaye, Schaler, did not return

phone calls.

Monetary suppart for the

project from the city may also

be weakening. A spOkesperson

for the Public Development

Corporation (PDC), Which is

backing the proiect on behalf of

the city, acknowledges that city

funding for the development

may be put on hold. "The POC

must reduce its capital spending

1 0 percent next year as part of

the city's overall spending cuts,

but there is no final decision yet

what those reductions would

be," says Lee Silberstein, a

spokesperson for POC. Calling

Atlantic Terminal a "high

priority," he says, "It wouldn't

fire ExIt After a fire in this building, 1724 Crotona Park East, the city

ordered homesteaders from the Inner City Press/Community on the

Move group to vacate the building as well as an adjacent property,

1728 Crotona Park East. Some of the homesteaders have been offered

alternative housing. but now Bronx Borough President Fernando

Ferrer is requesting inspections of a number of other Community on

the Move buildings in the Bronx.

be cut, but it might be deferred"

to next year.

Rose's attorneys have only

said the developer is loaking to

bring equity portners into the

project, according to attorneys

for the ATURA Coalition, which

is challenging the UDAG.

If there are changes either in

the developer or the scope of

the project, new approvals may

be needed and provide a new

opportunity for community

groups to influence the project.

But what types of reapprovels

would be needed would depend

on the changes that are sought,

Rothchild says.

Attorneys for Rose and the

ATURA Coalition are scheduled

to argue motions on the UDAG

case in federal district court this

month. The suit claims the

UDAG grant violates the 1986

Fair Housing Ad because the

federal Housing and Urban

Development agency did not

consider secondary disploce-

ment of low income residents

when awarding the grant.

A suit filed in state court

challenging the Board of

Estimate's approval because it

did not considerdisplacement

was dismissed by the state Court

of Appeals last ye(]r. A TURA' s

Clean Air Act challenge lost in

federal District Court.

One other suit, filed by a

block association that is

challenging new traffic patterns

in the area around the project,

remains. 0 Todd BreuI

AIDS HOUSING

MONEY

New York City officials and

AIDS activists are hoping to

receive more than $25 million

from the federal government to

pravide housing for with

AIDS and AIDS-related illnesses.

The money is expected to

come from a new hOusing

program known as the AIDS

Housing Opportunities Act,

which wos included in the 1990

National Affordable Housing

Act approved by Congress in

October. The bill authorized

$156 million for the next fiscal

year, subject to budget appro-

priations approval.

Rep. Charles E. Schumer (D-

Brooklyn), one of the act's spon-

sors, says New York City would

receive abaut $26 million if the

bill is fully funded by Congress

for the next fiscal year. In addi-

tion, the city would be eligible to

compete for further money

distributed as grants from the

federal Department of Housing

and Urban Development.

Jennifer Kimball, a spokes-

person for the Dinkins admini-

stration, says, 'We hope the

money is appropriated. AIDS

housing is a vital issue."

The AIDS housing bill is the

first substantive federal ack-

nowledgment of the severity of

the housing crisis for peaple

with AIDS. According to esti-

mates by the Partnership for the

Homeless, there are currently

some 32,000 homeless people

with AIDS nationwide. About

one-quarter of them live in New

York City, where with

AIDS comprise the fostest

growing segment of the

homeless population.

Peter Smith of the Partnership

for the Homeless acknowleck1es

that the $26 million that couTd

be available to the city doesn't

nearly approach the need. "But

this is a huge step forward

when what wos available before

was zero," says Smith.

The bill includes funding for

a variety of programs, including

the development of community

residences and single-room-

occupancy apartments with

supportive services and rental

subsidies earmarked for people

with AIDS. Federal housing

programs in existance befOre

the passage of the bill were not

applicable to people with AIDS

beCause the hOusing department

does not consider AIDS a

disability.

According to Smith, some

250 people with AIDS languish

unnecessarify-ond

New york City

hospitals each day. Hospitals

cannot release patients Who

have-no home to return to. 0

em LIMITS/JANUARY 1991/15

By Erika Mallin

Shining Star

For love and almost no money, Winnie McCarthy runs

the Star of the Sea shelter for women.

S

he once was a businesswoman

with a comfortable house out-

side of Boston. Now Winnie

McCarthy lives in a small room

in a shelter for the homeless in Queens.

She didn't lose her job, become desti-

tute or for some reason or other slip

into the margins. What she did was

dedicate her life to helping the home-

less by working at the Star of the Sea

women's shelter in South Jamaica.

The Star of the Sea's logo is a haloed

figure with welcoming arms sur-

rounded by a beaming star. McCarthy

says this is a symbol of the shelter as

a beacon of hope in a sea of suffering.

What she doesn't mention is that she

herself seems to embody this image.

On even the grayest South Jamaica

days, McCarthy exudes energy and

hope, striding through the run-down

neighborhood and speaking as fast as

a sportscaster. And her white, shoul-

der-length hair frames her alert

face ... well, like a bright halo.

When McCarthy talks about the

homeless people she works with, she

expresses compassion: "The people

we see who come through the door are

not always gentle," she says. "What

we see is the anger of trying to survive.

But knowing a person one-on-one,

you see their gentleness and their

gifts." When McCarthy talks about

herself, she's not so generous. Asked

why she decided to move to Star of the

Sea at 145-32 South Road, she replies

swiftly: "I just wanted to do some-

thing more with my life." But behind

that one-line answer is the story of a

unique and spiritual commitment to

public service.

Becoming Involved

Winnie McCarthy was born and

raised outside of Boston in a working

class family. After 25 years as an

administrator in a paper company,

she left her job and became certified

as a home aide in order to care for her

mother in a nursing home. After her

mother died, she joined the Peace

Corps and served in the Philippines.

She later joined a Jesuit organization

and went to Washington state and

worked with the elderly. It was dur-

ing this time that she first became

a/JANUARY 1991/CITY UMITS

involved with the homeless.

"I used to stand on the street in the

bad part of town and watch the street

people," McCarthy remembers. "I

began noticing that they were being

kicked out ofthe local diners because

they had no money, so I got coffee

urns set up serving coffee on the street.

I was fearful at first, but within a

couple of weeks they were very kind

to me and wouldn't let anything hap-

pen to me."

After McCarthy returned to Massa-

chusetts, a friend told her the Star of

the Sea needed assistance and she

made her move. When asked a second

time about her decision, she says,"1

don't think of it as unusual. I don't

know what to say except I knew it was

We Ire all sisters

responsible for

each other

the right thing to do ... J always simply

trusted that God would provide." For

the past decade, McCarthy has volun-

teered her time and commitment to

Star of the Sea. This is the first year

that she will receive a salary.

It seems that the only way to ex-

plain McCarthy's depth of commit-

ment is religious faith. But like every-

thing else about this woman, this

devotion is hard to put into a neat

category. McCarthy is no longer a part

of the Jesuit community and she shuns

direct affiliation with the organized

church. Yet she is deeply religious.

With her, it seems, the relationship

with God is one-on -one and extremely

private. But it shapes everything she

does.

Originally founded by Sister

Angeline Rasomialay with the help of

the Pius V Church of Jamaica, the Star

of the Sea doesn't fit the standard

image of cavernous, dangerous shel-

ters for the homeless. Just 12 home-

less women and their children live

there, along with McCarthy and an-

other staff member, Haogi Dorsey. (A

third staff member, co-director Sheilla

Desert, is currently on leave.)

"Our philosophy is that we are all

sisters so we are all responsible for

each other," says McCarthy. This

translates into close relationships that

transcend the usual boundaries of

"staff member" and "client." And all

the women must either do chores at

the Star of the Sea or volunteer work

in the community.

Ivy, one of the shelter residents,

says, "When I first came to Star of the

Sea, I wasn't interested in anything,

but Winnie kept encouraging me,

saying I could do it." Ivy came to Star

of the Sea in 1988 after there was a fire

in her house and she was unable to

pay the rent. These days, the quiet 51

year old helps run the single-room-

occupancy house across the street and

she plans to attend York College to

study to become a social worker.

Star of the Sea's staff director,

Haiogi Dorsey, 29, says it is impos-

sible for residents to sit around and

waste their lives away at the Star of

the Sea. "It's too personal here, there

are too many eyeballs on you, too

many people interested in you. We

just try to break bad habits of poor self

image and [help people] learn what

they feel good about doing."

No City Money

Besides offering a close-knit, car-

ing environment for homeless women,

there is another aspect of Star of the

Sea that is far from usual: the shelter

relies solely on contributions and

grants and doesn't accept a penny of

money from the city. McCarthy says

this policy is a way to counter de-

pendence on institutions and encour-

age responsibility to the people in the

shelter and the local community.

This approach has attracted atten-

tion and numerous community people

have stories about Star of the Sea and

Winnie McCarthy. Rev. Anthony

DiLorenzo, who worked with Star of

the the Sea for five years, remembers

when prostitutes used to pack the

corners near the shelter. "Winnie used

to walk down the street with her big

dog, who couldn't hurt a flea, and

pass out cookies to the prostitutes and

gently tell them to leave and they

would go. They knew instinctively

she was compassionate, they even

would protect the shelter, helping the

elderly residents cross the street or do

errands."

1

The staff at the shel-

ter often attribute their

good fortune to faith.

They talk about the time

when 40 loaves ofbread

were donated to the

shelter but there was no

place to store them. The

next day the problem

was solved: two freez-

ers arrived on a truck.

Another time the shel-

ter was in need of some

extra volunteers and

Elizabeth Bartlett, an ad-

ministrator at the local

hospital, came to donate

furniture. That after-

noon she quit her job,

activated her social se-

curity and moved in to

help run the shelter. She

lived out the rest of her

life at Star of the Sea.

Permanent Housing

McCarthy's next ef-

forts focused on two

abandoned homes right

next door to the HUD

property. Aiming to cre-

ate small single-room-

occupancy homes, Mc-

Carthy bought the first

building from the city's

housing department and

proceeded to have it re-

habilitated. She then

raised funds to buy the

second home and re-

ceived money from the

state's Homeless Hous-

ing Assistance Program.

Looking down the block,

a volunteer for Star of

the Sea, Alice Ann El-

kin, declares, "We've got

the state, city and fed-

eral government in on

this one street!"

In the last decade

there have been a num-

ber of changes at Star of

the Sea. There was a

time, McCarthy recalls,

when most women

could find a job or a

place to live in about

three months. These

days the average stay is

more than a year. So it's

no surprise that the shel-

ter has branched out and

McCarthy has started to

eye abandoned build-

ings in the neighbor-

hood as a resource for

permanent housing.

CreIting CommunItr. Winnie McCarthy (third from left, in the back) surrounded

by residents and workers from Star of the Sea.

But this still isn't

enough to satisfy Mc-

Carthy. She's already

looking around the

corner to a two-story

house that she's trying

to renovate along with

the Veterans Service Cor-

poration, a local non-

profit group. The hoped-

for result is housing for

homeless veterans. She's

also keen to help develop

a youth and community

center two blocks away,

at the Arjune House on

Inwood Street. (The

Arjune House is the site

where policeman

Edward Byrne was killed

First she set her sights

on a dilapidated house directly across

the street. "Every day I watched that

house being vandalized, stripped of

all its plumbing, people carrying out

pieces and parts," McCarthy recalls.

When the house was completely

boarded-up, she made some enquiries

and found out that the property was

publicly owned by the federal Depart-

ment of Housing and Urban Develop-

ment (HUD). She asked HUD whether

she could purchase and rehabilitate

the property in early 1986. HUD re-

fused. But this didn't stop McCarthy.

She embarked on a one-woman cam-

paign of persuasion, deluging HUD

with letters and calling them at least

once a week. After about a year of

pressure, HUD finally relented and

agreed to lease her the house and give

her the right to purchase the property

as long as she could find money on

her own for rehabilitation.

True to form, McCarthy raised funds

through contributions, construction

materials were donated and labor was

provided free of charge by volunteers.

She spread news about the help she

needed through the Star of the Sea

newsletter, which has a circulation of

700 and goes to individuals, civic

groups and churches. The house is

now almost ready for its new occu-

pants, and will soon be sold to the

South East Queens Task Force, a

housing development corporation that

was created by McCarthy and Assem-

blywoman Barbara Clark and includes

more than 15 Jamaica community

groups and local and state officials.

in 1988 while protecting

a man who provided the city with in-

formation about local crack dealers.)

McCarthy says she'd like to see the

veterans volunteering at Arjune

House, tutoring young people in the

neighborhood. "There are all kinds of

ways to do things." she says. "We

have to bring all kinds of people and

groups together."

Already this' is happening in South

Jamaica, as Star of the Sea provides

shelter and helps develop housing

and a sense of community. When

summing up Winnie McCarthy's

contribution, Ivy puts it best: "I just

think she has a god-given gift for

loving." 0

Erika Mallin is a freelance writer liv-

ing in New York City.

CITY UMITS/JANUARY 1991/7

By Cory Johnson

Return Offenders

The city's welfare hotels are back in business.

Who's making money from the misery?

L

ate last June the Dinkins ad-

ministration proudly an-

nounced that all families would

finally be out of the city's mis-

erable welfare hotels by the end of

July. But the very next day

new families were arriv-

ing at those same hotels.

Six months later, the city's

welfare hotel business is

back in full swing.

While the city is assidu-

ously avoiding the most

notorious of the welfare

hotels, families are being

placed in hotels that fail

to meet court-ordered

standards because they do

not include bathrooms

and cooking facilities.

And the city is again dol-

ing out thousands of dol-

lars a day to hotel owners

that include tax evaders, a

convicted felon and oth-

ers with long histories of

running shabby hotels.

City officials say a sud-

den surge in homeless

families requesting shel-

ter has forced the return

of the welfare hotels. The

city began the year with

1,445 families in hotels

and by June had reduced

the number to just 157.

Now there are nearly four

times that number of fami-

lies in hotels, and the time

families are expected to

stay has doubled.

ing quickly," says Wackstein. "Word

travels fast and by June we began to

see this large increase in applica-

tions where we had never seen an

entry rate like that before. If the

Under pressure from

Congress, which foots half

the tab for sheltering fami-

DeiI VII: A homeless family outside the Allerton Hotel.

lies in hotels, in 1989 the city began

to discontinue using the hotels. In

their place, the city increased its

production of permanent and transi-

tional housing for the homeless (see

homeless family census, page 4).

The result, says Nancy Wackstein,

who heads the Mayor's Office for

Homelessness and SRO Housing, has

been an increase in the number of

families seeking assistance. "People

began to see that you could get out of

the hotels and into permanent hous-

a/JANUARY 1991/CITY UMITS

number of entries had stayed what

they were, we would have been fine."

Victim of Success?

Advocates for the homeless dis-

agree. They say the city didn't meet

its own construction schedule of

building at least 3,534 transitional

shelter units by the summer-it built

2,900-and failed to heed warnings

that the number of families seeking

shelter had begun to rise. "It is outra-

geous- that homeless families should

have to pay for the city's own faulty

planning," says Steven Banks, an

attorney with the Homeless Family

Rights Project.

Banks dismisses city officials'

contention that the upsurge in fami-

lies seeking shelter is the result of

word on the street that there was a

fast track to a new apartment. "Rather

than the city being the victim of their

own success, the families are suffer-

ing from the city's failures and short-

falls."

Now the city is filling

up the same hotels it said

it would empty by the end

of July and is violating a

court order by choosing

hotels with insufficient

facilities for families, po-

tentiall y risking the health

of hundreds of children.

Only the owners of the

welfare hotels stand to

benefit.

According to the

mayor's office, the proc-

ess of choosing which

hotels will get the city's

homeless business is con-

fidential. "We're trying to

choose the best ones we

can," says Wackstein, "but

a lot of hotels just don't

want to take these people."

This seems hard to be-

lieve, given the city's long

history of paying top dol-

lar for a squalid room. The

city now spends an aver-

age of $2 ,250 a month for a

hotel room-a tab that

would cover some of the

priciest apartments in

town. Even at the lowest

end of the scale, where the

city pays $65 a night for a

room, owners stand to

make nearly $2,000 for

sheltering a family for a

month.

Family Affair

Some hotel owners have appar-

ently thrived off the business. Four

of the 12 hotels the city is currently

using are operated by four family

members-Jacob and David Tepper

and Sol and Bruce Burger-who are

in a partnership that has run welfare

hotels in New Jersey as well. The city

has been using the family'S hotels for

at least seven years.

Today the city is sending nearly

half the families it places in hotels to

facilities operated by the family: the

Hamilton Place, Lincoln Atlantic,

Cross Bronx and Lincoln Court. Some

300 families are currently sheltered

in these four hotels, netting the family

close to $20,000 a day. Yet these

same hotels have a combined 207

housing code violations and an over-

due tax bill of $16,882, according to

city records.

Jacob Tepper doesn't find this

alarming. "I make very little money,"

he says from his car phone. "I'm not

getting rich." And he dismisses the

housing code violations as just a fact

of life. "The Hamilton Place has 104

violations, but you go into any apart-

ment building in the city and you are

going to find violations like that. I

am just trying to make a living. I'm a

hotel owner. What am I supposed to

do?"

One thing he did do was scrape

together the cash for a $3,000 cam-

paign contribution to Mayor David

Dinkins-the same man who as Man-

hattan borough president urged the

city to get out of the welfare hotel

business. Asked if he thought his

contribution would help get place-

ments of the city's homeless in his

partners' hotels, Tepper responds,

"Everything has an effect on ever-

thing, that's the way the city works."

Another longtime welfare hotel

profiteer who has resurfaced in re-

cent months is David Fuld. Fuld was

a part owner of some of the most

infamous welfare hotels in the 1980s:

the Latham in Manhattan, Jamaica

Arms in Queens and Brooklyn Arms

in Brooklyn. In its heyday, the

Brooklyn Arms ran up more than

600 housing code violations and the

city went to court to force the owners

to repair hazardous conditions. The

city also needed a court order to

Longtime hotel

profiteers are

resurfacing.

force Fuld and his partners to make

repairs at the Latham.

Now Fuld is taking in families at

two new locations: the Colonial and

Lawrence hotels in Queens. Last

August there wasn't a single home-

less family at either of these hotels;

63 families are now there. The two

hotels have 26 housing code viola-

tions and more than $2,600 in over-

due taxes, according to city records.

Fuld did not respond to numerous

phone calls. His attorney, Steven

Orlow, insisted that Fuld is out of

the country. But Louise Goodrich,

the manager of the Lawrence, says

Fuld was in town and that he calls in

for messages.

Illustrious Past

Another old-timer enjoying a re-

surgence in the homeless business is

Lawrence Meinwald, who ran the

Allerton, Allerton Annex and Madi-

son hotels. Meinwald has a particu-

larly illustrious past. In 1979, two

residents ofMeinwald's single-room-

occupancy Village Plaza Hotel swore

in affidavits that he threatened ten-

ants with a pistol, according to the

ViJIage Voice. Larry Klein, a former

head of the Mayor's Office for SRO

Housing, told the Voice that condi-

tions in that hotel were the worst of

any in the city.

In 1984, the city's Human Re-

sources Administration (HRA) an-

nounced it was going to stop sending

families to the Allerton and Allerton

Annex because Meinwald was se-

cretly shifting families into the

Madison, which the city had already

ceased using because of poor condi-

tions. Now the city is playing its own

version of hide-and-seek at the Aller-

ton Annex.

The annex doesn't show up on the

city's list of hotels currently being

used for families; it's found in the

category known as special residences,

which include facilities especially

for pregnant women and their

husbands or boyfriends. "After the

birth you might find they show up in

the Allerton under the 'family' sec-

tion of our list," says Vincent DiGesu

ofHRA. "But we don't place families

there [the Allerton] any more. They

just become families there." There

are 86 such nonfamilies at the annex.

Fittingly, Meinwald's name

doesn't appear on the Mayor's Office

"COMMITMENT"

SInce 1980 HEAT has provided low cost home heating oil. burner and boiler repair services.

and energy management and conservation services to largely minority low and middle income

neighborhoods in the Bronx. Brooklyn. Manhattan and Queens.

As a proponent of economic empowerment for revitalization of the city's communities. HEAT is

committed to assisting newly emerging managers and owners of buildings with the reduction of

energy costs (long recognized as the single most expensive area of building management) .

HEAT has presented tangible opportunities for tenant associations. housing coops. churches.

community organizations. homeowners and small businesses to gain substantial savings and

lower the costs of building operations.

Working collaboratively with other community service organizations with similar goals. and

working to establish its viability as a business entity. HEAT has committed its revenue gener-

ating capacity and potential to providing services that work for. and lead to. stable. productive

communities.

'I'IIrouP the primary service of providinB low cost home heatinI oil, v.rious heatinI

pant services Mel ener'D ...... ement services, HEAT members halve c:oIIectively

MYed over 55.1 .........

HOUSINC ENERCY ALLIANCE FOR TENANTS COOP CORP.

853 BROADWAY. SUITE 414. NEW YORK. N.Y. 10003 (212,505-0286

If you .... lnterested in -mInK more IIbout HEAT,

or if you .... interested in becom .... HEAT member,

QI or write the HEAT office.

CITY LlMll'SI]ANUARY 1991/.

of Homelessne.ss and SRO Housing

records as the owner or manager of

the Allerton. That title belongs to his

friend Carol Turner, who once barred

social workers attempting to assist

families in a Meinwald hotel. But the

city Finance Department's overdue

tax bill of nearl y $8,400 for the Aller-

ton is sent to the attention of Law-

rence Meinwald.

For years, Anthony Zito's Bayview

Hotel in Sheep shead Bay has been

one of the most expensive of the wel-

fare hotels used by the city. The city

spends more than $280,000 a month

to keep some 90 families at the

Bayview.

Judith Rossinow, the manager of

the Bayview says the hotel is now a

nonprofit "and it's one of the nicest

places in the city." She also says Zito

is no longer involved in operating

the hotel.

But Len Robertson of the Brooklyn

district attorney's office scoffs at that

claim. "It's common knowledge that

Zito runs the place. He just doesn't

want it publicized," says Robertson,

who has good reasons to keep tabs on

the Bayview's landlord.

In 1971 Zito was sentenced to four

years in prison for loan sharking. In

1983 Zito was indicted for failing to

pay the city more than $100,000 in

hotel occupancy taxes, but the case

was thrown out on technical grounds.

From October 1984 to February 1985

and again in 1987 the FBI had the

Bayview under electronic surveil-

lance-leaders of the Luchese crime

family met regularly there with paint-

ers union officials to discuss bid-

rigging and labor "peace," according

to a court affidavit. In 1987 Zito was

arrested on charges of paying two

bribes totaling $3,500 to an under-

cover agent posing as a city inspec-

tor. Zito pled guilty and received

five years probation.

Among the other hotels being used

by the city to shelter homeless fami-

lies with young children, there are

few candidates for the do-gooder's

hall of fame. Mitch Suss, the owner

of the Bronx Park Hotel, owes the

state more than $187,000 for with-

holding taxes deducted from employ-

ees, pay checks but never paid to

!I

authorities, according to state tax

department records. And Rashmi

Mehta's Cosmopolitan Hotel mixes

its welfare family business with an

hourly rate for the "hot sheets" trade.

Chances are business for all these

hotel owners-and others like them-

will continue to grow in the coming

months. For all the mayor's talk about

the rights of every New Yorker to

have a decent place to live, the ad-

ministration seems incapable of fol-

lowing through.

"I'll be honest with you," says

Nancy Wackstein from the mayor's

office. "There are other priorities.

The public has spoken and they say

they want more cops. Building hous-

ing is too expensive. The city's legal

requirement is only for emergency

housing. If you're looking for the city

to provide housing for all of these

people . . . well it just isn't going to

happen." 0

Cory Johnson is a journalist who has

written articles for New York

magazine, Time Warner's FYI and

the Village Voice.

Bankers Trust Company

Community Development Group

A resource for the non ... profit

development community

Gary Hattem,Vice President

280 Park Avenue, 19West New York, New York 10017

Tel:212,850,3487 FAX:212,850,2380

10/JANUARY 1991/CITY UMrrs

Case in Point:

Williamsburg Court

This 59 unit low income housing develop-

ment, sponsored by the St. Nicholas

Neighborhood Preservation Corporation,

is located in Brooklyn's Williamsburg

section.

They needed $300,000 to complete

their $7 million plus financing package.

Could Brooklyn Union's Area Develop-

ment Fund help?

Sure we could-with a little help from

our friends, the l.ow Housing

Fund and Bankers Trust Company. They

each pledged $100,000 to match

Brooklyn Union's investment.

We've found that the Area Develop-

ment Fund is a working blueprint for

change in the economic and social life

of New York. If your company would

like to help as has Pfizer, Bankers Trust

Company and so many others, talk to

Jan Childress at (718) 403-2583. You'll

find him working for a stronger New York

at Brooklyn Union Gas, naturally.

GaS,

. Naturally

CITY UMITS/JANUARY 1991/11

For Whom Does the

Port Authority Toll?

The Port Authority looks and acts like a private corporation.

They need to be reminded they're not.

BY DOUG TURETSI(Y

T

he next time you're backed up in traffic, waiting

to plunk a fistful of bucks into the hand of a toll

taker at one of the bridges or tunnels stretching

from New Jersey to New York, consider this: The

Port Authority of New York and New Jersey,

which controls the Hudson River crossings, has an annual

budget of nearly $3 billion. That's more than the nearby

states of Maine, New Hampshire and Vermont. Besides

the bridges and tunnels, the Port Authority owns or

operates some three dozen facilities in the metropolitan

area, including the World Trade Center, the airports and

the PATH train. The Port Authority itself employs more

12/JANUARY 1991/CITY UMITS

than 8,000 people-and even has its own police force.

But unless you're a commuter, angered by constant tie-

ups at the bridges or tunnels or the latest threat of a toll

hike, chances are you don't give much thought to the Port

Authority. This relative anonymity may suit port officials

just fine. But since the agency is fed with taxpayer money

and is supposed to serve the public, it is worthy of serious

attention.

The first public authority in the nation, the Port Author-

ity is crucial to the local economy. According to the

agency's own figures, its airports generate some 243,700

jobs and $6.6 billion in salaries; its marine terminals

account for another 180,000 jobs and $4.5 billion in

salaries. The port agency operates-and in some cases

built-much of the city's vital transportation infrastruc-

ture.1t was created to bolster shipping activity at the ports,

but as the agency has grown and prospered, it has changed

course and undertaken glitzy real estate deals with ques-

tionable public benefits. Many say its time for the Port

Authority to get back to basics, but because of the way it

was set up, legislative officials and citizens have little in-

fluence over the agency's activities.

the Port Authority has grown and changed," says Goldmark.

Yet the question of whether the Port Authority was

reacting to changes or he!ping to accelerate them remains.

Take the piers in the five boroughs, for example. Once the

heart of the bustling Port of New York, most of what's left

of the shipping trade has moved to New Jersey docks. To

the Port Authority, it was easier to build new cargo ports

on the wide open shores of Elizabeth

and Newark than on the more con- Unless there's greater public interest

and oversight, the Port Authority will

continue to chart its own course.

Port Town

When the legislatures of New York

and New Jersey formed the Port Au-

thorityin 1921, New York's port was

preeminent in the country and at the

center of international trade. Ships

from Europe, South America, Asia

and the Caribbean steamed to and

from the city's piers. With the city's

docks thriving, local manufacturers

The Port Authority's

empire includes the

port, airports,

bridges, and the

World Trade Center

gested waterfront stretches of

Brooklyn or Manhattan. Yet many

experts argue that this was simply

short -sighted.

Even when a New York venture

like the Red Hook container port

proved to be highly successful, the

port agency appeared reluctant to ac-

knowledge it. Rather than quickly

expanding the facility, the Port Au-

thority engaged the operators of the

container port and public officials in

boomed as well. For tens of thou-

sands of immigrants, blacks migrating from the south and

other workers with limited skills, jobs flowed from the

city's waterfront.

The Port Authority's first-and only-responsibility

was to ensure the continued growth of port commerce.

Central to this was the improvement of the freight railways

that served the piers. No direct rail access existed across

the Hudson. To move goods west into the nation's heart-

land freight had to travel all the way to a small town near

Albany. The Port Authority was charged with construct-

ing a rail freight tunnel from Bay Ridge, Brooklyn, to

Greenville Yard in Jersey City, forging a direct railway link

to the rest of the country. The Port Authority'S first

chairman, Eugenius Outerbridge, called this project the

"keystone" of the agency's mission.

Nearly 70 years later, no such tunnel exists and the

region's port is no longer predominant. In a 20-year period

stretching from 1967 to 1987, the Port of New York's share

of the nation's cargo dropped by 50 percent. Piers in the

five boroughs are moribund. That decline has mirrored

the city's alarming loss of manufacturing jobs, with some

200,000 industrial jobs disappearing since 1979.

But the Port Authority continued to grow and play an

increasingly large role in the local economy. With reve-

nues streaming in from its bridges, tunnels and airports,

the Port Authority sought new outlets for expansion and

carved a new agenda for itself. This new agenda has

included such controversial real estate projects as the

World Trade Center and proposed waterfront luxury

developments in Hunters Point, Queens and Hoboken,

New Jersey. To John McHugh, an attorney specializing in

transportation issues and a longtime critic of the Port

Authority, the agency has ignored its mandate in favor of

real estate deals and other projects that produce few well-

paying long-term jobs for working class New Yorkers.

"The lroblem is freight. The Port Authority was con-

ceive because of freight," says McHugh.

But Peter Goldmark, the executive director of the Port

Authority from 1977 to 1985 who now heads the Rockefeller

Foundation, argues that such a viewpoint is misguided,

ignoring the authority'S ability to adapt to changing needs

and economics. "As the region has grown and changed,

an arcane debate over the size of con-

tainers handled.

It seems the port agency decided New York's piers

simply weren't worth the effort."I think the Port Authority

repeatedly fails in its mission to promote the port, to en-

hance the port in respect to New York City," says Steven

DiBrienza, chairman of the City Council's subcommittee

on the waterfront.

Changing Times

The Port Authority dramatically altered its role in the

regional economy in 1961. Its agreement to build the

World Trade Center and take over the bankrupt Hudson

and Manhattan commuter rail line-now known as the

PATH train-marked two important changes in the port

agency's agenda. The construction of the 110-story twin

towers was a formidable leap into real estate develop-

ment; the purchase of the PATH became the agency's

wedge against further involvement in railways.

The Port Authority was urged into the trade center

project by David Rockefeller, the chairman of Chase Man-

hattan Bank. Chase had just primed the downtown land-

scape with its Chase Plaza project and was seeking further

development to escalate local real estate values. The twin

towers were just the thing. And to push the project before

the Port Authority Rockefeller had an important sup-

porter-his brother Nelson, the governor of New York.

The only public officials with power over the Port

Authority are the state governors, who appoint the agency's

board of commissioners and can veto board decisions. But

before New Jersey's governor would agree to the huge

investment by the Port Authority in New York, he wanted

something for his state. The PATH train was the answer.

The Port Authority had long resisted taking over the

PATH. For years, agency officials had seen rail lines as

just money losing propositions. But now that it wanted to

build the World Trade Center, the Port Authority needed

to give something to New Jersey in exchange. Agreeing to

buy the PATH was the perfect salve for New Jersey.

Cleverly, the Port Authority exacted its own price in the

bargain. Agency officials added a restriction to their bond

notes that effectively prohibited the Port Authority from

further investments in railroads. The covenants forbade

the Port Authority from taking on any future rail projects

CITY UMrrs/JANUARY 1991/13

if the new projects

combined with the

PATH would create

deficits exceeding

one-tenth of the

agency's reserve

funds.

When the state

legislatures at-

tempted to repeal this

rule-and force the

port agency to build

much needed rail

links to the airports-

U. S. Trust Company,

a friend of the Port

Authority, filed suit.

According to "The

Public's Business" by

Annmarie Hauck

Walsh, the company

held some $100 mil-

lion in Port Authority

bonds and U.S.

Trust's former chair-

man, Hoyt Ammidon,

sat on the authority's

board. Not only did

U.S. Trust win its case

before the Supreme

Court, but the Port

Authority picked up

the tab for legal fees.

two waterfront devel-

opment plans-one

on each side of the

Hudson to satisfy the

governors. The plan

for Hunters Point calls

for the construction

of one of the largest

developments in the

city's history. It

would include more

than 6,000 luxury

apartments, two mil-

lion square feet of

office space and a 350-

room hotel. It was

approved by city offi-

cials despite heated

opposition from the

local community (see

City Limits, Aug/Sept

1990). It's no small

irony that one of the

Port Authority's ma-

jor real estate project's

is adjacent to the city's

strongest industrial

neighborhood. Esca-

lating land values

sparked by the devel-

opment pose a direct

threat to the area's

blue-collar economy,

the very same econ-

omy at the heart of

the Port Authority's

original purpose.

The construction

of the World Trade

Center proved re-

markably profitable

for the Port Author-

ity. It was also con-

troversial. While

there were few-if

any-private compa-

nies willing to build

unglamorous facili-

ties such as intermo-

dal freight yards,

there were plenty of

private developers

Missilll the Boat: Critics say the Port Authority doesn't pay enough attention to

unglamorous duties like minding the New York ports.

The Hoboken

waterfront plan is

nearly as huge as its

Queens counterpart.

Calling for some 3.2

million square feet of

luxury residential

and commercial

space in waterfront

high-rises, the project

is just as controver-

itching to get behind spanking new projects. Critics said a

governmental agency like the Port Authority simply

shouldn't be involved in speculative real estate deals-

especially when it gets to erect its buildings tax free. (Last

year alone the Port Authority'S tax-exempt World Trade

Center cost the city's coffers some $59 million in property

taxes.)

Jump Start

But the floodgate was already open and in the early

1980s, the Port Authority solidified its role in develop-

ment. Looking at the declining waterfront in Hunters

Point and Hoboken, port officials began planning two

massive new real estate developments. In the wake of New

York's fiscal crisis of the 70s, many saw real estate devel-

opment as the way to jump start the local economy.

The Port Authority has committed $250 million to the

14/JANUARY 1991/CITY UMITS

sial as Hunters Point. A referendum passed last summer

opposing the Port Authority's plan for Hoboken hasn't

stopped the agency from continuing to push the water-

front project. "We have been fighting them for 10 years,"

says Sada Fretz of Hoboken's Coalition for a Better Water-

front. "Another developer would have packed up and left.

The fact they've stayed shows how powerful they are."

Even as former Port Authority executive director

Stephen Berger launched a back-to-basics $5.4 billion,

five-year capital program directed at improving transpor-

tation networks, port facilities and area airports in 1987,

the agency continued to flirt with real estate deals. Last

year, the agency was prepared to grant Brooklyn Heights

piers 1 to 5 to developers Arthur Cohen and Larry Silver-

stein for just $150,000, a future payment based on the size

of any project built there and a cut of future profits. Well-

connected Brooklyn Heights activists were able to torpedo

the deal, but it is rare that

community activists have

any influence on Port Au-

thority plans.

Now the Port Author-

ity looks more like an

international conglomer-

ate than a government-

created agency, with far-

flung trade offices and a

diversified portfolio that

includes industrial parks,

an office project for New-

ark-based legal firms and

an incineration plant

under construction in

New Jersey. To Stanley

Brezenoff, the former first

deputy mayor of New

York who is now execu-

tive director of the port

agency, it's time to link

such projects to more

basic Port Authority serv-

ices. "We need to think in

terms of economic devel-

opment as tying our eco-

nomic development proj-

ects to our basic func-

tions," says Brezenoff of

his plan to reemphasize

the agency's role in mass

transportation and marine

freight. But Brezenoffhas

no intention of side-track-

ing the real estate deals.

Tunnel VISion: The Port Authority has poured money into bridges and tunnels from New York to New Jersey.

The result: more gridlock and air pollution.

Bonded

How can an agency so big be so relatively little known?

Part of the answer lies in the fact the agency has such

limited accountability to the public and elected officials.

Only the governors have direct influence over the au-

thority, but even they use their power sparingly. Since the

Rockefeller administration, New York's governors have

paid only sporadic attention to the port agency, adding to

its relative anonymity on this side of the Hudson. But

there's one set of voices the Port Authority listens to very

closely: the bond market.

While the regional economy has taken a nose dive, the

Port Authority remains flush. The recent move to hike

tolls and the PATH fare was pegged to the agency's

ongoing multi-billion dollar construction program. The

Port Authority's capital for such programs comes from

bonds it floats against projected tolls, fares, rents and other

revenues. Unlike New York City'S bonds, which have

been put on credit watch, the Port Authority'S remain

sound. Todd Whitestone, a managing director at Standard

& Poor's, says this is "based on [the Port Authority's] wide

variety of revenue sources and relatively strong financial

position."

This stands to reason. The board has always been

dominated by corporate and financial leaders. At the Port

Authority'S helm have been men-the agency's 12-mem-

ber board of commissioners has been an almost exclu-

sively male enclave-from major financial and invest-

ment institutions in the region. In the fast, Bankers Trust

and Mutual Benefit and the Prudentia insurance compa-

nies have each had representatives on the Port Authority's

board for dozens of years. The authority's current chair-

man, Richard Leone, is a past president of the New York

Mercantile Exchange and until 1989 was a managing

director at Dillon Read & Company, a leading brokerage

firm. Other current board members include Robert Van

Buren, the president and chief executive officer of Mid-

lantic Corp., a huge bank holding corporation, and Wil-

liam Ronan and former New York mayor Robert Wagner,

directors of Crossland Savings Bank.

Such connections between the Port Authority and

major financial and investment firms mean more than just

a back-slapping comraderie. The agency emphasizes reve-

nue-making projects as a means of preserving its inde-

pendence from political influence and government con-

trol. The trade-off is a dependence on the demands of the

bond market, where the Port Authority acquires its capital

for expansion. The result is a public agency that operates

much like a private venture, measuring its projects by rate

of return rather than broader social assessments. Rick

Cohen, the former director of Housing and Economic

Development in Jersey City, which lies in the heart of

authority'S domain, asks, "Does the Port Authority have a

different mission than the LeFrak Organization?"

Bottom-Line Works

The insularity of the board is reflected in its bottom-line

response to public works. -An unreleased 1980 Port Au-

CITY UMIfS/JANUARY 1991/15

thority market study of the long-neglected freight tunnel

project revealed a wealth of public benefits. Projecting

into the 1990s the study estimated the freight tunnel

would remove some 1,700 trucks from the area's highways

each day, reducing traffic, road maintenance and air

pollution. Additionally, the study estimated that a $1

billion investment to construct the cross harbor tunnel

would generate some $600 million in wages, $250 million

in business income, $54 million in regional income and

sales tax and $163 million in federal tax revenues. Today,

there's still no tunnel in the works-the project never

materialized because there's no way such broad public

benefits could be reflected in the agency's own balance

sheets.

Likewise, the agency also often fails to integrate its

efforts with the needs of nearby communities. Says Stephen

Strahs, director of the Tri-State Economic Justice Net-

work, a coalition of 10 community and labor groups,

"Over the years the Port Authority has not been attentive

to the needs of the low income communities near its

faciliijes." He argues that the Port Authority should be

using its $5.4 billion capital plan for airport and other

reconstruction projects as a means for creating an invalu-

able job-training program. Strahs' group has also just

proposed that the port agency create a $30 million com-

munity capital fund for loans to businesses that will

employ disadvantaged workers. Fund investments would

be based on both monetary and social return.

Activists aren't the only ones who have said the agency

should be more accountable to communities. In 1952 a

congressional committee suggested the Port Authority

create a board less dominated by corporate interests. Yet

the authority's board still lacks even a single member who

could be said to represent community, labor or other

perspectives.

Early Days

The genesis of the Port Authority of New York and New

Jersey was a long squabble between the two states. For

dozens of years the states waged head-to-head competi-

tion over port business. Much of the competition stemmed

from the haphazard growth of railroads serving the Port of

New York. New Jersey officials also complained that

railroads shipping goods east failed to charge for the cost

of ferrying cargo-laden rail cars across the Hudson to New

York's ports.

In 1916 complaints over railroad rates finally led to a

formal action before the Interstate Commerce Commis-

sion, with New Jerseyites demanding that rates to their.

side of the Hudson be lowered. Two years later a special

bi-state commission formed to address the issue. Their

eventual recommendation: the creation of the Port Au-

thority of New York and New Jersey to ease the competi-

tion by improving rail links and terminals and promoting

business for the entire port region.

This new agency-then called just the Port of New

York Authority-was the first of its kind in the United

States. Created by government, this new entity could

operate much like a private business. Known as a public

authority, it was freed of many of the legal, administrative

and financial restraints imposed on a traditional govern-

mental agency. The public authority could buy, lease or

operate facilities and collect revenues, which, in turn,

would be plowed back into its own operations. Although

the public authority couldn't levy taxes, it had another

la/JANUARY 1991/CII'Y UMITS

incredibly lucrative way to generate funds for its own

expansion: The Port Authority could sell bonds to Wall

Street investors.

The concept of public authorities sprang from the turn-

of-the-century Progressive movement. To these reformers

the inefficiency, patronage and corruption that plagued so

many government efforts could be cured by an essentially

business-like approach towards public administration.

Civic-minded business leaders, like the Progressive re-

formers themselves, would make decisions based on ra-

tional assessments rather than political influence. (That

business leaders possessed their own biases and political

relationships apparently never concerned the Progres-

sives.)

Despite its corporate foundation, the Port Authority has

not always been a rollicking success. It wasn't until 1931,

when the Holland Tunnel was turned over to the Port

Authority and the agency's coffers began to fill with the

nickels and dimes of commuters, that it had a profitable

venture. Likewise, the local airports that have become

highly lucrative Port Authority projects were originally

built by the city. (The Port Authority gained control ofthe

airports in 1947 after a battle between two legendary

public authority titans-Robert Moses and Austin Tobin,

who headed the port agency for some 30 years.) And the

World Trade Center, the towering symbols of the Port

Authority's empire, was initially bolstered by state leases

for office space.

In the years since its inception, the Port Authority has

become the model for similar public authorities through-

out the country, from the federal Tennessee Valley Au-

thority to such local entities as New York's Housing

Development Corporation. Robert Moses, New York's

"master builder," built much of his empire through the

free reign afforded him under the rubric of public authori-

ties.

As the Port Authority grew prosperous from its bridges,

tunnels and airports, the agency looked for new ways to

secure revenues. The development ofreal estate, whether

as luxury condos or industrial parks, appeared to fit the

bill. But all the new buildings in the world won't help keep

jobs in the area if businesses can't move freight through

the city's congested streets. "The heart of the beast is being

able to move goods in and out," says Anthony Riccio, a

former commissioner of New York's Department of Ports

and Trade.

Yet it's just this role as regional transportation planner

that the Port Authority had distanced itself from. Much of

the so-called economic development activity in the city is

focused on tax abatements for office towers.

It's an expense that may be more profitably applied to

nuts-and-bolts projects. Annmarie Hauck Walsh writes in

"Urban Politics New York Style," "Yet all of the highways,

loans, partnerships, industrial parks and tax abatements ...

cannot produce a fraction of the economic advantage that

low cost and efficient freight access to the container port

facilities and to the interstate lines could have provided

for manufacturing in the boroughs of New York City."

With its nine-figure budget, the Port Authority will

continue to playa central role in shaping New York's

future. That's why a growing chorus of critics say it's time

to pay closer attention to the agency and make sure it gets

routed onto the public's track. 0

Research assistance by Elizabeth von Nardroff.

Moving Towards Self-Sufficiency:

Critical Challenges In Difficult Times

THE PARTNERSHIP FOR THE HOMELESS

ACTION DAY '91

Join us on January 26th (gam-3:30pm)

The New School for Social Research

66 West 12th Street, Manhattan

Hon. Ruth Messinger, President,

Borough of Manhattan,

Keynote Speaker

Hon. Stephen J. Norman, Ass't Commissioner,

NYC Dep't of Housing Preservation and Development,

Homeless Housing Development

Peter P. Smith, Chair,

City Council Legislative Advisory Commission on The Homeless

Panels and Workshops on Homeless Health and Mental Health Care, Welfare Reform, Affordable Housing

Strategies, Models of Self-Sufficiency, Homeless and HIV/AIDS, Revisiting the Welfare Hotels, and more.

No fee. Lunch will be provided. To register, return form

to: The Partnership for the Homeless, 110 West 32nd

Street, New York, NY 10001-3274. Due to limited

seating, reservations must be in by January 21, 1991.

For additional informationcall Rosa Cintron, (212) 947-

3444.

1------------------

I Registration Fom

I Name ____________ _

I Address ____________ _

I City State Zip _

I Phone Affiliation ___ _

Competitively Priced Insurance

~ have been providing low-cost insurance programs and quality service

for HOFC's, TENANTS, COMMUNITY MANAGEMENT and other NONPROFIT

organizations for the past 10 years.

Our Coverages Include:

UABIUTY BONDS DIRECTORS'. OFFICERS' UABIUTY

SPECIAL BUILDING PACKAGES

"Uberal Payment Terms"

[W

DUD

306 FIFTH AVE.

o 0 Q NEW YORK, N.V. 10001

(212) 279-8300

ASSOCIATES INC. Ask for: Bala Ramanathan

LET US DO A FREE EVAWATION OF

YOUR INSURANCE NEEDS

CITY UMITS/JANUARY 1991/17

l I a ' a " ' ~ ' t I

By Steve Rosenbush

Commons Concerns

Melrose Commons won't be for the common

people of the South Bronx.

D

olorinda liSanti recites with

pride each step she and her

husband have taken to make a

comfortable home out of the

small South Bronx apartment build-

ing they bought six years ago from the

city. Most ofthe big jobs-new walls,

new pipes, new wir-

ing-are finished .

Now they tend to de-

tails such as the new

marble threshold in

the doorway to the

bathroom.

"I go little by little

and all my money is

involved here," she

says, explaining that

she and her husband

never borrowed

money to work on the

building, which did

not even have run-

ning water when they

moved in as tenants.

revitalization of the South Bronx.

Grassroots community groups are

dead set against the project, which

will receive public funding but pro-

vide no new housing for low income

families, even though the median

income in the area is less than $10,000

potholes, drug activity is constant and

the city owns approximately 60 per-

cent of the property. To carry out the

proposal, the city intends to establish

a Melrose Commons Urban Renewal

Area.

The new development would in-

clude more than 3,000 new units of

housing and 750 apartments in reha-

bilitated city-owned buildings. City

officials estimate that the new apart-

ments would sell for between $90,000

and $120,000, making them afford-

able for families with incomes from

the upper $20,000 range to $53,000.

The project would

stretch from 156th to

163rd streets and

from Park to St. Ann's

avenues.

She is 54 and her

husband Guiseppe, a

retired construction

worker, is 65. They

came from Italy 25

years ago. Theirthree

kids, ages 19,21 and

22, all live at home.

There are several ten-

Rubble Ind R'-II: This section of the Bronx may one day include thousands of

condominiums.

There are currently

about 950 house-

holds in the area. Ac-

cording to the city's

housing department,

two-thirds of these

families would re-

main in buildings

that are due for reha-

bilitation, but the oth-

ers-including the

LiSanti's-would be

relocated. Officials

from the city say ren-

ters will receive as-

sistance from the city

to find new apart-

ments and home-

owners will be reim-

bursed for the ap-

praised value of their

property. LiSanti

ants who live in the other apartments

of the building and relatives live next

door. "It is like our blood here," li-

Santi says. "It is our future."

But the city has other plans for the

liSanti's three-story walk-up at 811

Courtlandt Avenue in Melrose. The

city plans to tear it down-to make

room for Melrose Commons, a major

new development proposal that would

displace numerous local residents and

businesses to clear space for the con-

struction of more than 3,000 apart-

ments for moderate and middle in-