Professional Documents

Culture Documents

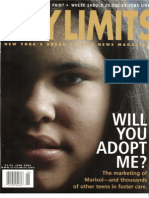

City Limits Magazine, February 1997 Issue

Uploaded by

City Limits (New York)Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

City Limits Magazine, February 1997 Issue

Uploaded by

City Limits (New York)Copyright:

Available Formats

HBRUARY 1997 $1.

00

r

Fixing Broken Buildings

L

ate last month, Mayor Rudolph Giuliani announced he had reas-

signed his housing commissioner, Lilliam Barrios-Paoli, to take

over the city agency that runs welfare programs. That evening the

usual pundits appeared on New York One cable news. One of them

described Barrios-Paoli as the city's commissioner of personnel-a post

she hasn't held for nearly a year. Her housing job wasn't noted.

That says it all. These days, housing is such a

I " _ " ' _ ~ - " " " " ' ' ' - fringe issue for the policy elite that City Hall jour-

nalists barely notice what's up at the Department of

Housing Preservation and Development (HPD).

Mayor Giuliani could change this by choosing a

ED ITO R I A l skilled, aggressive and politically savvy new hous-

ing commissioner-and giving him or her authority

to pursue a serious agenda around housing quality

and affordability. It's a good time for such a move: to win reelection,

Giuliani needs support from the neighborhoods where his political cur-

rency is now nearly worthless-low-income and working class black and

Latino districts hit hard by government cutbacks.

So far, the mayor's disinterest in housing has been very clear. Of late,

HPD's overriding concern has been to sell tax liens held by the city on hun-

dreds of privately owned buildings and to tum thousands of city-owned

properties over to private property managers, developers, nonprofits and

tenants. Capital funding for new development has been all but eliminated.

Less than a year ago, high level officials circulated a memo through City

Hall proposing that HPD be dismantled.

Mayor Giuliani espouses a "broken windows" theory of policing that

calls for zero tolerance of such offenses as vandalism and public drink-

ing. If he really cares about the quality of life for all New Yorkers, he

should take that theory to its logical next step-and become intolerant of

the terribly dilapidated and overcrowded housing conditions that prolif-

erate in uptown Manhattan, Central Brooklyn, Jamaica and large sec-

tions of the Bronx.

We need a commissioner who will complete and make public the

much-touted computerized early warning system to identify housing at

risk. More importantly, we need a commissioner who will use govern-

ment power effectively to prevent abandonment and preserve housing

quality, easing the cost-burden for good owners-and cutting the lifeline

for profiteering mortgage holders and incompetent landlords.

And we need a mayor and a commissioner who will lobby for ade-

quate funding for affordable housing from Washington and Albany; who

will take a public stand recognizing the deepening crisis in housing

affordability, and who will support organized tenants in their fights to

secure decent homes.

This is an excellent time to shift to a higher gear.

Andrew White

Editor

Cover illustration by Aaron Meshon

City Limits

Volume XXII Number 2

City Limits is published ten times per year, monthly except

bi-monthly issues in June/ July and AugusVSeptember, by

the City Limits Community Information Service, Inc., a non-

profit organization devoted to disseminating information

concerning neighborhood revitalization.

Editor: Andrew White

Senior Editors: Kierna Mayo, Kim Nauer, Glenn Thrush

Managing Editor: Robin Epstein

Contributing Editors: James Bradley, Rob Polner

Design Directi on: James Conrad, Paul V Leone

Adverti sing Representative: Faith Wiggins

Proofreader: Sandy Socolar

Photographers: Dietmar Liz-Lepiorz, Melissa Cooperman

Associate Director,

Center for an Urban Future: Neil Kleiman

Sponsors:

Association for Neighborhood and

Housing Development, Inc.

Pratt Institute Center for Community

and Environmental Development

Urban Homesteading Assistance Board

Board of Directors:

Eddie Bautista, New York Lawyers for

the Public Interest

Beverly Cheuvront, City Harvest

Shawn Dove, Rheedlen Centers

Celia Irvine, ANHD

Francine Justa, Neighborhood Housing Services

Errol Louis, Central Brooklyn Partnership

Rebecca Reich, Low Income Housing Fund

Andrew Reicher. UHAB

Tom Robbins, Journalist

Doug Turetsky, former City Limits Editor

Pete Williams, National Urban League

'Affiliations for identification only.

Subscription rates are: for individuals and community

groups, $25/Dne Year, $35/Two Years; for businesses,

foundations, banks, government agencies and libraries,

$35/Dne Year, $50/Two Years. Low income, unemployed,

$10/Dne Year.

City Limits welcomes comments and article contributions.

Please include a stamped, self-addressed envelope for

return manuscripts. Material in City Limits does not neces-

sarily reflect the opinion of the sponsoring organizations.

Send correspondence to: City Limits, 40 Prince SI.. New

Yorl<, NY 10012. Postmaster: Send address changes to City

Limits, 40 Prince St, NYC 10012.

Periodical postage paid

New York, NY 10001

City Limits (lSSN 0199-0330)

(212) 925-9820

FAX (212) 966-3407

e-mail : CitLim@aoLcom

Copyright 1997. All Rights Reserved. No

portion or portions of this journal may be reprinted with-

out the express permission of the publishers.

City Limits is indexed in the Alternative Press

Index and the Avery Index to Architectural

Periodicals and is available on microfilm from University

Microfilms International, Ann Arbor, MI 48106.

CITY LIMITS

FEBRUARY 1997

FEATURES

Throne Together

The Latin Kings court unity and redemption at the Three Kings celebration.

Photos by Dietmar Liz-Lepiorz

Ten-PAC

Some pundits say the influence of political action committees is waning.

But in New York, where the perception of power is as important as the real thing, a

player without a PAC is prey. City Limits picks ten power PACs you need to watch.

By James Bradley

Cell's Angels

Politicians would just as soon send teenage felons away ' til they' re old and

frail. Some teens, however, are getting a second chance-and proving that second

chances are a good idea. By Pam Frederick

PIPELINES

Murphy's Flaw

Father Louis Gigante's takeover of the South Bronx's Murphy Consolidated

housing project was the first step in the city's privatization of public housing manage-

ment. But tenants say they're trapped in a game of musical sl umlords.

By Glenn Thrush

New Lords of Flatbush

New York's latest immigrants are reviving the city's economy, no matter

what the neo-Know Nothings say. Say hello to the entrepreneurs and professionals

whose huddled Master Cards are yeaming to breathe free. By Sasha Abramsky

PROFILES

Across the Ages

A Union Settlement program matches kids with community elders, bridging the gap

between New York generations. By Kierna Mayo

COMMENTARY

Cityview [29

NYPD Strategy Number 9 By Yohance Maqubela

Cityview [30

Makeshift Miracle By Harry DeRienzo

Review [31

Boomerpang By Dimitry Leger

Spare Change [34

Bench Warmers By Thomas Kamber

DEPARTMENTS

Briefs &, 7 Editorial 2

All 's Ferrer in Landlord Land

Letters 4

NYCHA's Abusive Policy

Professional

Living Wage Works Directory 32

Housing Funds Dry Up

Job Ads 33,35

LETTERS i

,

Assigning Cullt

Max Block's piece "Justice in Flames"

[December 1996] omitted a central charge

in the case against Edwin Smith for the

murder of a firefighter. The issue was not

that Smith had started the flre, which even

the prosecutor accepted as accidental, but

that he had not told firefighters and police

on the scene that the building was empty.

But such information, when offered by

a homeless drug addict, is not likely to be

believed or even heard. I doubt Smith

could have influenced the firefighters '

course of action and I imagine that he

knew he would be seen as irrelevant, irri-

tating and interfering.

Block concludes that "Smith is respon-

sible." He's not. The mayor, whose poli-

cies force New Yorkers to build fires of

animal fat and trash in the basements of

abandoned buildings in order to avoid

freezing to death, murdered Lieutenant

John Clancy.

Jeanne Bergman

Housing Works

Max Block replies: The central charge in

the Smith case, at least in legal terms,

was recklessness. That is, it wasn't so

much a concern of the judge or the pros-

ecutor whether the fire had been an acci-

dent or whether Smith failed to tell fire-

fighters the building was empty. The crux

of the prosecutor's case was that Smith

acted recklessly when he rigged his

makeshift heater. The guilty verdict on

that charge, in combination with the

death of a firefighter on the scene,

allowed for the murder charge. That's

what sent Smith to prison.

Bergman is partly correct in that

Smith's failure to warn the firefighters

became an issue-but only insofar as it

was bandied about by the district attor-

ney to convince the jury and the press

that Smith belonged behind bars. The DA

used the story to chip away at Smith's

character.

As far as the argument that Giuliani's

policies are to blame for Lt. Clancy's

death, I fear that a charge like that ulti-

mately obscures an important implication

of the verdict: Anyone of us could face the

same charges Smith faced if we are forced

to heat our homes in a makeshift way. Still,

the point is a good one. Hats off to

Bergman and Housing Works.

~ F

For 20Years

We've Been There

ForYou.

of

NEW YORK

INCORPORATED

Your

Neighborhood

Housing

Insurance

Specialist

R&F OF NEW YORK, INC. has a special

department obtaining and servicing insurance for

tenants, low-income co-ops and not-for-profit

community groups. We have developed competitive

insurance programs based on a careful evaluation

of the special needs of our customers. We have

been a leader from the start and are dedicated to

the people of New York City.

For In/ormation call:

Ingrid Kaminski, Executive Vice President

R&F of New York

One Wall Street Court

New York, NY 10005-3302

212 269-8080 800 635-6002 212 269-8112 (fax)

F

Journalists Hay. ethics?

While I enjoyed your 20th anniversary

issue (November 1996), I take issue with

former editor Annette Fuentes' cavalier

recounting of her faked cover photo.

''Donning a rumpled old raincoat I dug out

of my closet... yours truly became a despair-

ing woman seeking shelter at a Red Cross

facility near Times Square," she writes.

She should have dug her ethics out of

the same closet!

What kind of message does that send?

Faked photos undermine the credibility of

your reporting!

AB Klaus

Borough Park

The editor replies: Nope, there's no fakery

going on here. To our knowLedge no one has

"reenacted" anything in our pages since

Fuentes' jlil1ation with the fuzzy edges of

journalism more than 10 years ago. And IW

one will in thefL/ture. Still, we were first, well

ahead of ABC's notorious (fake) secret-cam-

era video of spies trading briefcases-and

before the whoLe genre of television fakery a

la Inside Edition erupted in our living rooms.

Fuentes' comments were just a little self-crit-

icism with a solid sense of humor attached.

Reach 20,000

readers in the

nonprofit sector,

government

and property

management.

ADVERTISE

IN

CITY

LIMITS

Call Faith Wiggins at

(212) 925-9820 or

(91 7)-792-8426

CITY LIMITS

~ ... ..... ............... ............. ........ .

,

t

Dolores (Dee) Solomon in her

newly renovated shop, Dee's Cards N

Wedding Services

CALL: CHASE COMMUNITY

DEVELOPMENT COMMERCIAL

LENDING 212-332-4061

Moving in the right direction

Happy Renovation Dee!

When Dolores (Dee) Solomon went after a much needed

loan to keep her struggling small business competitive she

thought it was a "mission impossible". And it was. Then

Thelma Russell, her longtime branch manager at The

Chase Manhattan Bank branch at 125th Street, connected

her to the right people.

Thelma personally introduced Dolores to the business

lending officers of the Chase Community Development

Group. Working one-on-one as a team, they customized a

loan package for Dolores. They did it with Chase's flexible

"CAN*DO" lending program which makes special

allowances for the credit challenges facing many

community-based businesses.

Dolores got her loan and business has never been better.

Stop by her shop at 480 Lenox Avenue and see for your-

self. It just goes to show you: success is still all about mak-

ing the right relationships.

; ........................... ~ Community Development Group

CHASE. The right relationship is everything.

8M

1996 The Chase Manhattan Bank. Member FDIC.

Protestors from the Gay and Lesbian Anti-Violence Project rally in front

of Brooklyn 0 A. Charles Hynes' Kensington home in January. Hynes IS

seeking the death penalty against a gay man accused of killing his lover

LIVING WAGE WORKS

Labor and community campaigns

demanding that cities require munic-

ipal contractors to pay employees a

living wage are gaining momentum

nationwide, Measures are pending

in Boston, Chicago, Houston, Los

Angeles, Minneapolis, and New

Orleans. But they are facing increas-

ingly effective opposition from offi-

cials and business interests.

Opponents recently defeated

ballot initiatives in Missouri and

Montana and quashed a proposal in

Denver. In Albuquerque, the city

clerk's office derailed a living wage

campaign by disqualifying 1,000 of

the signatures on election petitions,

Resour(es

HERE'S WHY THE KIDS ARE NOT

ALL RIGHT: Of 64 inmates surveyed

recently at the Spofford Juvenile

Detention (enter in the Bronx, almost

half know cops personally, but only a

ACORN is challenging this ploy in

court.

But a new study evaluating the

impact of Baltimore's 1994 living

wage ordinance debunks critics'

claims that the living wage would

greatly increase contract costs, lead

to layoffs and alienate business.

Issued by the Preamble Centerfor

Public Policy, a year-old Washington-

based organization, the study says

that Baltimore's contract costs did

increase last year-but by only one-

quarter of one percent The cost of

enforcing the law were minimal-17

cents per taxpayer. There were no

layoffs due to higher labor costs.

third have ever had contact with

coaches or counselors. The survey,

conducted by Youth Force, a Bronx-

based advocacy group, also found

that all 64 say they value education

and most plan to go to college. In

truth, however, only one in 10 stu-

dents in poor neighborhoods goes to

HOUSING FUNDS DRY UP

There's a one-word explanation

for why there are far fewer mental -

ly ill men and women living on the

streets today than there were just

five years ago: Housing. Since the

late 1980s, New York has created

nearly 13,000 new beds in commu-

nity-based residences for home-

less, mentally ill men and women,

the majority of them in the city.

That pace of development is

coming to a halt as funding runs

out. The nonprofit groups that run

the existing housing say their resi -

dences are filled to capacity.

"It's much harder to place peo-

ple now," says Steven Coe, execu-

tive director of Community Access,

an organization that houses hun-

dreds of the mentally disabled on

the Lower East Side. "Our intake is

a trickle because we don't have

space."

In 1990, state and city officials

signed a five-year agreement to

provide permanent housing to more

than 7,000 homeless. But in 1994,

Governor Pataki canceled the final

300 units and the agreement

expired soon afterwards. The last

units in the pipeline are scheduled

for completion this spring and so

far, neither Giuliani nor Pataki

extended the effort.

In fact, contractors told

researchers the living wage require-

ment "levels the playing field" and

"relieves pressure on employers to

squeeze labor costs in order to win

low-bid contracts,"

Finally, the study rebuts the

charge that a mandate to pay

above-poverty-Ievel wages will

cause capital flight, an argument

Mayor Giuliani cited when he

vetoed New York's living wage legis-

lation last year, which was later

overridden by the City Council. In

Baltimore, the value of local busi-

ness assets, which had declined for

the previous four years, increased

4.6 percent since the law's passage,

Philomena Mariani

college. One in four wind up in a juvie

lo(kup. For a copy of the upcoming

report call (718) 665-4268.

PERMANENT HOUSING MAY BE BETTER

THAN A HOMELESS SHELTER,

but the Giuliani bureaucracy often

blocks the path. So says a survey due

Yet in 1993, the state Office of

Mental Health estimated the city

needed housing for at least 14,000

more mentally ill homeless people.

Brooklyn Assemblyman Jim

Brennan and a group of advocates

are pushing Albany for new capital

to develop 2,000 rooms in support-

ed, single room occupancy-style

buildings. The group, which

includes the Coalition for the

Homeless, Community Access and

several other organizations, is also

calling for new rent subsidies to

move thousands of people from

community residences into private

apartments.

Recent research has found that

a majority of the city's shelter beds

are used by a relatively few needy

men and women, many of them

mentally disabled, who could be

housed far more cheaply in sup-

ported housing. This could free up

shelter beds for the thousands of

short-term homeless who need a

place to stay.

Last month, as shelters for sin-

gles reached peak capacity of

7,400, the city prepared to open a

new shelter for 380 men in Central

Brooklyn for $6 million.

Albany, however, is not likely to

move quickly, if at all. "I'd be sur-

prised if we could pull together a

new agreement before June," says

Shelly Nortz of the Coalition for the

Homeless. There's a need to move

fast. ''I'm approaching gridlock,"

says Peter Campanelli, president

of the Institute for Community

Living, the largest provider of

housing for the mentally disabled

in the city, ''I' m down to the last

five or six supported housing

vacancies out of more than 200. I

have to hold people in transitional

beds that are more expensive

because there are no apartments

for them. I've never had to do this

before."

The Governor's office failed to

return calls on the issue. A

spokesman for Mayor Giuliani had

no comment. Andrew White

out this month from the Emergency

Allian(e for Homeless Families and the

Tier-2 (oalition, a group of nonprofit

shelter operators. They report that

families are averaging nine months in

shelters before they move into an

apartment-three months longer than

in past years. Applications for rent

CITY LIMITS

B

ALfS FERRER IN lANDLORD lAND

unpaid rent in an escrow

account as a condition of hav-

ing their cases heard in hous-

ing court. The city's top land-

lord lobbying group, the Rent

Stabilization Association, has

long pushed the measure. The

RSA's chief, Joe Strasburg, is

a close friend of Ferrer's.

Bronx Borough President

Fernando Ferrer is a public

champion of tenants' rights,

but his bid to become New

York's first Puerto Rican mayor

is being bolstered by real

estate money-more than

$160,000 worth.

A City Limits analysis of

Ferrer's campaign finance fil-

ings shows that the BP has

taken $20,000 from PAC's asso-

ciated with the city's top land-

lord lobbying group since 1994.

Other real estate interests-

from individual landlords,

developers, management com-

panies and real estate-related

law firms-chipped in $140,000

to Ferrer in the year ending

January 15, 1997.

In all, Ferrer raised a total of

about $1.1 million in that period.

Bronx Beep Freddie Ferrer has taken $160,000 from

real estate interests in his bid to become mayor.

According to state filings,

PACs associated with RSA

have not given funds to any

other likely Democratic may-

oral challenger.

BRIEFS

Despite taking the contribu-

tions, Ferrer has said he sup-

ports the extension of rent con-

trol and rent stabilization and

has blasted Republicans in the

state senate for threatening to

block renewal of rent regula-

tions in Albany this spring. The

BP's campaign office did not

return phone calls, but in a "irresponsible in the extreme."

The vast majority of

Ferrer's real estate money

came from independent com-

panies, most headquartered

outside of the Bronx, which

has the lowest per capita

income of any city borough.

The largest lump-$17,500--

came from a quartet of man-

agement companies head-

quartered in Great Neck, Long

Island, at the address of

Boulevard Realty Corp. And in

a textbook case of bundling,

nearly $10,000 came from 20

different lawyers and the cor-

porate coffers of the law firm

of Borah Goldstein Altschuler

Schwartz-one of the city's

most prominent real estate law

firms. Glenn Thrush

statement faxed to City Limits, But Ferrer has supported a

Ferrer labeled senate Majority measure opposed by many ten-

Leader Joe Bruno's plan to ant organizations that would

annihilate rent regulations as require tenants to deposit

NYCHA'S ABUSIVE POLICY

A New York City Housing

Authority policy designed to prevent

convicted criminals from moving into

apartments is putting battered

women at risk, according to Legal

Aid lawyers.

In preliminary motions on a new

class action lawsuit, up to 3,500

women who applied for public

housing apartments charge that

NYCHA's excessively stringent

screening process is forcing them

to reveal their wherea bouts to the

abusive men in their lives. The pol-

icy is intended to force prospec-

tive tenants to prove they no

longer live with ex-boyfriends and

husbands who have criminal

subsidies are frequently lost by the

city and welfare cases are dosed for

no reason. The Alliance is based at

The Gtizens Committee for Children,

(212) 673-1800.

FEBRUARY 1997

records.

The suit, filed by the Legal Aid

Society, says the women may have

been illegally denied apartments as

a result of NYCHA's beefed-up

screening process.

"The idea that a woman should

have to get in touch with her abuser

just to satisfy a bureaucrat's idea of

proof is absolutely absurd," said

Dorchen Liebholdt, director of

Sanctuary for Families Center for

Battered Women's Legal Services, a

co-plaintiff on the suit.

A NYCHA spokesperson refused

to comment on the ongoing litigation.

Until last April, women were

required to provide three pieces of

THE 104TH CONGRESS IS HISTORY,

BUT ITS LEGACY LIVES ON,

The balanced budget agreement and

the new welfare law were only the

most visible elements of the 104th's

assault on antipoverty programs,

according to an appraisal just pub-

lished by the Washington-based

identification from their former

husbands or boyfriends to prove

they lived separately. While that

policy has been revised, Legal Aid

charges that the new, more

vaguely worded requirements are

just as bad. Although the agency

allowed some of the women to

move into apartments, attorney

Judith Goldiner of Legal Aid says

the old policy is being quietly

enforced. Many women who were

previously rejected are now hav-

ing their cases put in a bureau-

cratic limbo while the authority

figures out what to do next. "You

have women who are trying to

hide from these abusive guys and

Center for Community Change. And

much of last year's agenda is likely

to be revived soon.

As early as this month, for

example, conservatives are likely to

make an aggressive new push for a

balanced budget. And House

Republicans also have reintroduced

NYCHA was making them track

them down and make contact,"

said Goldiner.

In one case described in court

documents, the authority is mulling

the fate of a Lower East Side

woman initially refused an apart-

ment because her drug-dealer ex-

boyfriend lived with her in NYCHA

housing during the early 1990s. The

man lives in Brooklyn today, and is

so abusive that she has obtained on

an order of protection against him.

While waiting for the city's deci-

sion, the woman has been forced to

double-up with her mother-who,

she says, has begun beating her

and her child.

The lawsuit is not expected to be

resolved until later this year, accord-

ing to Goldiner. Glenn Thrush

their radical plan for the overhaul

of the federal public housing laws.

This time around, the Senate is

more likely to approve it. Be pre-

pared.

for a copy, call (202) 342-0567.

D

CityLimits

Takes the

out of

Wall Street.

By moving there.

Our new address,

as of March 1:

120 Wall Street

20th Floor,

New York, NY

1000

5

Three offices available,

good transportation,

conference rooms,

full facilities.

275 Seventh Avenue

(25th Street),

15th Floor,

New York, NY 10001.

Contact Irma Gonzalez

at (212) 929-7604.

Ext. 3018

I' I I II \ \1 I; I{ () I, I I( \ (, I I" (

When it comes

to insurance ...

We've got

you covered.

"3.'.

we work closely with ow' customers

F

or over 40 years, Pelham Brokerage

Inc. has responded to the needs of

our clients with creative, low-cost

insurance programs. We represent all

major insurance carriers specializing in

coverages for Social Servi ce organ-

izations. Our programs are approved by

City, State and Federal funding agencies.

to insure compliance on insurance

requirements throughout the develop-

ment process. Thereafter, we wiU tailor

a permanent insurance program to meet

the specific needs of your organization.

Let us be part of your management

team. A specialists in the area of

new construction and rehabilitation

of existing multiple unit properties,

Our clients include many of the leading

organizations in the New York City area

providing ocial services.

For information caU:

Steven Potolsky, President

111 Great Neck Road, Great eck, New York 11021 Phone (516) 482-5765 Fa..< (516) i82-5837

I " " I I( \ " ( I

Development Leadership Network

A national network of community development practitioners

National Retreat: March 6 - 8, 1997

Calistoga, CA

Debate and discuss the themes of individual and

neighborhood "selFsufficiency" at this year's DLN retreat.

Network with peers!

Meet and hear stories from development practitioners nationally.

Learn some best (and not so best) practices from around the country.

Relax and enjoy!

Experience Calistoga'S incredible mud baths and hot springs. Calistoga is just

one hour from San Francisco and accessible by public transportation.

Sign up now!

Registration is $125 and includes two lunches and continental breakfasts.

Accommodations range from $40 to $ 8 9 per night.

For immediate information contact: Kim Ball

11148 Harper, Detroit, MI 48213 (313) 571-2800 x121 FAX (313) 571-7307

DLNHQ@aol.com

CITY LIMITS

Across the Ages

A unique program finds common ground between young

New Yorkers and their elders. By Kierna Mayo

A

strange thing is happening

this afternoon at the East

River Senior Center in East

Harlem. Instead of elderly

people walking slowly

through the door, the place is filling up

with lively teens. Gloria Zelaya, coordina-

tor of an intergenerational program run by

the Union Settlement Association Services

for Older Adults, anxiously awaits their

because they take it from there."

Zelaya says the program has been

working well since last October and serves

as a model for intergenerational relation-

ship-building. The program works in col-

laboration with Elders Share the Arts, a

Brooklyn-based group that creates inter-

generational partnerships through expres-

sive arts like drama and dance. ESA pro-

vides "legacy work" workshops for the

Adrianna on the cold walk to Hodge's

apartment building on East I 10th Street.

Adrianna and Charles have been visiting

Hodge regularly for weeks now. The rou-

tine is basic: Get to the Lehman Village

Houses. Wait 10 minutes for the one

working elevator to arrive. Ring Miss

Hodge's bell. Smile, be nice. Walk her to

the local market. Bring her and her stuff

back home.

arrival. "What the kids do,"

he explains, "is serve home-

bound seniors."

If it sounds simple, that 's

because in a lot of ways it is.

Basically, the senior center

serves as an after-school

home-base where the high

In pairs, the teens hit the

streets and ring the doorbells

of community elders.

This simple routine makes

all the difference to Hodge,

who is severely arthritic in her

left hand and who also suffers

from what she calls "infantile

paralysis"-that is, polio. "I

had something of a stroke

when I was two. My hands

shake. I don't baby myself,

though. When you see me

baby myself, you know I don't

feel good," she insists.

schoolers can mix, mingle,

drop off their bags and make

phone calls. Then, in pairs,

usually a boy and a girl, they

hit the streets and ring the

doorbells of community

elders w:th hopes of provid-

ing some company and, more

likely, some help.

III find myself thinking about

how lonely they get, " admits

Alexander, a 76-year-old.

The most surprising ele-

ment of the intergenerational

program is the bonding many

participants experience around

common interests. "Being

with one senior in particular

felt like I was with my grand-

father who passed away," says

Yadira, a 12th grader. He

asked me what I wanted to be.

In many other ways,

though, the work these young

people do is not simple at all.

Although the trips to the

supermarket are easy enough,

III would never want to

be that lonely. "

the mental exercise of bonding with "old

people" can be quite a challenge. "I find

myself thinking about how lonely they

get," admits Alexander. a l6-year-old. "I

would never want to be that lonely."

Feelings of Ambivalence

In fact , many teens find that, through

the program, initial feelings of ambiva-

lence about the plight of the elderly, their

history and current realities are slowly

transformed into more humble feelings of

respect and admiration. "You have to call

them first and give them time," says anoth-

er teen explaining the process of connect-

ing with a senior. "And talking over the

phone is the most difficult thing. They

don't know you, you don't know them.

Basically you don't talk about their past,

you just explain what the program is about

and cover the basic stuff. From there we

start talking about their life, but really we

don' t have to ask that many questions

FEBRUARY 1997

Union Settlement program, says Zelaya,

and they have come in handy breaking the

ice between teens and seniors. One exam-

ple of the legacy work is the family trees

the teens and seniors of the Union

Settlement Intergenerational Program

complete and share. "[Through them]

some people find out fascinating things.

Some do really have intere ling histories,"

says the director.

Seventy-five year old Helen Hodge is

no exception. "I'm a native New Yorker,"

she says. "But my parents were born in St.

Thomas. I graduated [high school] in '37.

I did factory assembly work, work for the

Amalgamated Union. Lets see, that was,

oh, '41." Hodge has a remarkable memo-

ry. She can tell you the dates of birth and

death of all 12 of her siblings, her parents'

anniversary date in 1908, and other signif-

icant events in her life. For her, construct-

jng a family tree was no problem.

"Miss Hodge is, like, real nice," says

When I said a social worker, he said, 'Social

worker? I used to be a social worker for 28

years.' I found that we had a lot in common.

He's a Gemini, me too. It's funny."

It's Natural

At the senior center, Zalaya challenges

the young people to discuss changes they

have made in their lives as a result of their

experiences working with the elderly.

"When you see elderly people in the morn-

ing, like on the train, you have a lot more

patience," says Alexander. "One time

these elderly women were in front of me

and they were moving so slow, they made

me miss the train. I didn't say, 'Oh, man,

would you move? You made me miss the

train.' You just look at it like, they missed

the train also.

"I'd stereotyped old people as slow.

Many of them are slow. But for good rea-

son-it's natural for them to be like that.

Man, I'm gonna be old one day, too." _

PROFILE ~

l

PIPEliNE "

SEBCO's

management has left

a massive hole in

Mattie Roberts '

bathroom ceiling for

nearly six nWllths.

leM

Murphy's Flaw

Since Father Gigante took over the dtys'Murphy Consolidated

housing project, almost everything that could go wrong

for tenants has. By Glenn Thrush

A

hot bath is a cruel thing to

deny an 85-year-old

woman, but Mattie

Roberts is not what you

would call a complainer.

When a pipe in the apartment upstairs

burst and flooded last August, obliterating

most of her bathroom ceiling, she squared

her jaw and watched as the workman

tramped in and out.

"We'll be back soon to fix it," they said.

So Mrs. Roberts settled back in front of

the television and a snack tray crowded

with prescription bottles, Iinaments and

aches-and-cricks sundries and waited.

"The bathtub was nice," she laments in a

whisper that can barely contend with the

TV in her immaculately kept one-bedroom

South Bronx apartment. "I used to use that

tub, but I can't use it now. They still ain't

fixed that ceiling."

Mrs. Roberts' tub

has handicapped

accessible grip bars

and anti-slide

footholds. But it's

useless, constantly

filthy, a collector of

plaster dust, water-

bugs and whatever

else happens to drop

down from the 20-

square foot void

where the ceiling

should be.

It 's also a

metaphor for a priva-

tization scheme gone

awry. Fixing the hole

is the responsibility of

the SEBCO Manage-

ment Company,

which won a $2.75

million contract from

the New York City

Housing Authority

(NYCHA) to manage

its Murphy Consoli-

dated housing project,

an 850-apartment

jumble of townhous-

es, small apartment

buildings and con-

verted brownstones.

In all, Murphy

Consoli-dated's 72

buildings are scat-

tered throughout a 25-

block radius in the

South Bronx neigh-

borhoods of Crotona

Park East, Longwood

and Hunts Point. The

F

Housing Authority has owned them for

more than 15 years; most of the properties

were taken by the federal government from

landlords in foreclosure proceedings two

decades ago.

SEBCO's chief-the man the city

picked three years ago to oversee

Murphy's management-is Father Loui s

Gigante, a former City Councilman who

runs one of the Bronx's most powerful

low-income housing empires. He also hap-

pens to be brother and confidante of reput-

ed Genovese crime family boss Vincent

"The Chin" Gigante.

For most South Bronx residents, the

SEBCO name-short for Southeast Bronx

Development Corporation-refers to a net-

work of nonprofit development and social

service agencies. The SEBCO Management

Company shares the name-but it is actual-

ly a for-profit Gigante set up to manage the

nonprofit's buildings. And the income from

the NYCHA contract is going directly into

the private company's bank account.

According to a 1989 investigation by

Village Voice reporter William Bastone,

the priest, who owns several Manhattan

and upstate New York residences, used

mob-connected contractors in the develop-

ment of the 2,500-plus units SEBCO pro-

duced in the South Bronx. Still, even crit-

ics concede Gigante's management com-

pany keeps most of the buildings he devel-

oped in excellent condition.

The same cannot be said about the

NYCHA properties managed by SEBCO.

In two dozen interviews with City Limits,

many residents say the new maintenance

contract has been a failure. SEBCO-

installed floors have buckled within

months after they were put in; roofs in

many of the Murphy buildings have

chronic leaks; tenants claim that patch-up

repairs in response to their heat and water

complaints have left them cold. And then

there's an assortment of smaller ills that

go months without being repaired:

cracked tiles, busted closet doors,

unpainted walls, crippled oven-ranges

and water damage.

In South Bronx communities awash in

crack and heroin, SEBCO and NYCHA

managers have allowed security doors and

lobby windows to remain broken and

unrepaired for months at a time. The lassi-

tude encourages dealers to continue to

peddle their wares in the buildings, despite

claims that SEBCO management would

clean up the buildings.

"This here is everybody's get-high

building," says Mary Chambliss, who has

lived in her first-floor Murphy

Consolidated apartment on Hunts Point

CITVLlMITS

Avenue for seven years. Chambliss is

especially incensed by the fact that across

the street, in buildings SEBCO developed,

vigilant maintenance and banks of strate-

gically-placed security cameras have cre-

ated a practically drug-free zone.

"Second-class citizens, that's what we

are," she says.

"I'm starting to wonder if things

weren't actually better under the Housing

Authority. And things were bad then,"

adds David Pyatt, a Bryant Avenue tenant

who had to wait months to have the hole in

his bathroom ceiling repaired. He says his

stove has been broken for a year.

On th. Privatization Block

It is hard to tell whether to blame

SEBCO or NYCHA for the Murphy

buildings' flaws. Calls to Father Gigante,

who has reportedly been spending much

of his time counseling The Chin in prepa-

ration for his upcoming trial, were not

returned. And David Post, a SEBCO

manager, referred all calls to the Housing

Authority and hung up when pressed for

answers.

But there is a lot more at stake here

than Father Gigante's reputation. For

years, public housing authorities around

the country have been contracting out

management services to private-sector

companies. The SEBCO contract was the

first of its size in New York City. If the

pilot effort succeeds, NYCHA sources say,

the city will consider farming out the man-

agement of more than 20,000 low-rise

authority units to private managers.

Three years ago, as part of the authori-

ty's recognition that it had long misman-

aged Murphy and other non-conventional

housing projects, NYCHA Chairman

Ruben Franco requested bidders for the

new contract. He chose SEBCO from II

companies that submitted bids. In part, the

authority selected the firm because of its

track record.

Two much smaller, non-conventional

NYCHA holdings also were contracted to

private companies. Neither has had the

problems Murphy has had. Part of the rea-

son is that Murphy has the poorest tenants

of the group and the worst maintenance

history,

So why were so many maintenance

companies eager to take on the Murphy

management contract?

Simple. They wanted to buy in on the

ground floor of what could be one of the

largest privatization gold mines in New

York: the management of NYCHA'S vast

stock of smaller apartment buildings.

"There's a very, very big pot of gold at

FEBRUARY 1997

the end of this," says one real estate execu-

tive who didn't want his name used.

"I think this is the model for the pri va-

tization of the 20 to 25,000 scattered site

buildings NYCHA's been mismanaging for

years," says Phil Thompson, a former high-

ranking authority official who pushed for

NYCHA to privatize management of its

odd-lot buildings. "The idea is the tum all

of these buildings over to community-

based non profits and for-profits that would

be a lot better at managing them."

Shatt.red Window Pan

Things looked sunny when SEBCO

first began taking over Murphy sites two

years ago.

In June 1995, the Daily News reported

that the company's management of the

Murphy building at 875 Irvine Street in

Hunts Point was helping to clear the

building of heroin dealers who had run

the place for years. According to the

paper, the clean-up was bolstered by

"innovative" management techniques,

namely the hiring a live-in super and

security guards.

"It's our showplace," bragged SEBCO's

housing manager, Cono Depaola.

Today, winter gusts blow through the

shattered window panes of the show-

place's front entrance. The lock on the

"security" door rattles around uselessly in

its socket. Anyone who pushes it can get

into the building. On the roof it's the same

story: the emergency-exit fire alarm has

been smashed and the roof door flaps in

the wind.

Tenants and police say drug dealers,

most of whom live in other parts of the

neighborhood, sell and store heroin in the

lobby and in some apartments.

"It's just as bad as it's ever been," says

Esther Benitez, former head of the build-

ing's tenant association. NYCHA says it

replaced the building's front door four

times in December alone and won't do so

again until a contractor installs a new mag-

netic lock in mid-February.

The broken door is a perfect example of

the philosophy-espoused by Mayor

Rudolph Giuliani and former Police Chief

William Bratton-that the slow repair of

vandalized buildings is an invitation to

criminals. On one recent morning a tenant

leaving the building to run a few errands

found herself facing a sight she had never

seen before: a neat queue of 20 customers

impatient for their daily heroin buy.

The SEBCO security patrols haven't

really had much of an effect. "The securi-

ty guys get paid about minimum wage," a

local cop explains. "They don't have guns.

I don't even think they've got nightsticks.

No vests. If you were in their place, would

you be confronting drug dealers? They' re

no deterrent."

Around the corner, on Hunts Point

Avenue--one of the city's most notorious

drug drags-a row of to more Murphy

buildings slouch behind the crack vials

strewn on their stoops. The SEBCO-owned

apartment houses across the street gleam,

sealed behind locked doors and the aegis of

roof-mounted security cameras.

The type of new magnetic doors that

NYCHA says will soon be installed at 875

Irvine Street haven't provided much secu-

rity on the Hunts Point Avenue buildings.

Five of them are broken and tenants say

they have been that way for months. A

sixth door is so bent that it simply needs to

be shoved to get it open. A seventh has a

perfectly functional lock-but the two

panes of security glass above it have been

neatly punched out.

"The crackheads walk right in here, ail

hours," says l6-year-old Roxanne

Rodriguez, who lives with her grandmoth-

er and uncle in a ground-floor flat at 835

Hunts Point Ave. "There are two little girls

who live in the second floor and they got

to walk past this every time they come

home from school."

Mary Chambliss, who lives a few doors

down the avenue, says that crackheads and

junkies treat the hallway outside her front

door like it was their living room. "I open

my door and the crack bottles roll right in.

There are needles in the hallway right out-

side. Sometimes they pee and it comes in

through under my door. It's disgusting."

As with other inquiries, SEBCO would

not officially respond, but maintenance

workers say the problem with the front

door locks was NYCHA's fault.

"We call in the broken doors to

NYCHA every day," says one super who

identified himself as "Smiley." "Housing

knows about them, but they haven't done

anything yet. It's their whole bureaucracy.

They haven't approved all of the

requests."

A Pla.tlc Tarp

Mattie Roberts says she has called the

SEBCO repair office numerous times and

gotten nowhere. "A few weeks ago, a man

came in, looked at [the hole above the

bathtub 1 and said, 'I can't fix this. '"

NYCHA Spokesman Hilly Gross says

SEBCO maintenance crews first reported

the ceiling collapse in November. He

blames the repair delay on the upstairs

tenant who won't open her door to

SEBCO crews.

-,

e-

"How come nobody even bothered to

put plastic over the hole?" Roberts replies.

Leaks are a problem throughout the

project. A woman who lives in one of the

39 apartments at 1317 West Farms Road

says her family unrolls a plastic tarp to lay

on the living room carpet every time it

rains-even though the ceiling has been

repaired twice.

Although Gross and SEBCO mainte-

nance workers say almost all the Murphy

buildings' boilers are in good condition,

there are heat problems in many apart-

ments. During most of the 20 or so unan-

nounced, dead-of-winter visits conducted

by City Limits, ovens were fired up to

supplement apartment radiators, which

were either cold or only slightly warm.

Roxanne Rodriguez's 57-year-old

grandmother needs to sleep in her

clothes-under four blankets-most win-

ter nights. Roxanne's infant nephew gets

Nev# York Lay,yers

for the Public Interest

provides free legal referrals for community-based and non-profit groups

seeking pro bono representation. Projects include corporate, tax and real

estate work, zoning advice, housing and employment discrimination,

environmental justice, disability and civil rights.

For further information,

call NYLPI at (212) 727-2270.

There is no charge for NYLPI's services.

Specializing in

Community Development Groups,

HDFCs and Non ... Profits

Low ... Cost Insurance and Quality Service.

NANCY HARDY

Insurance Broker

Over 20 Years of Experience.

270 North Avenue, New Rochelle, NY 10801

914,654,8667

similar treatment.

And Xanthea Gibbons, who lives in

1002 East 167th Street, a six-story

Murphy building located next door to

SEBCO's office, says she hasn ' t had heat

for over a year. Asked how many times

she's called for help, Gibbons begins

counting, then lets out a tired chuckle.

"Oh, please," she says.

POinting Fingers

If SEBCO and the housing authority

are trying to maintain a unified front in

public, they have been pointing fingers at

each other behind closed doors.

Housing authority officials, speaking

on condition of anonymity, say they ques-

tion SEBCO's will to put maintenance pri-

orities over profit. Father Gigante and his

employees maintain they haven' t been

given enough money to make long-

neglected repairs and charge that

NYCHA's paper-mill bureaucracy has

been impossible to negotiate.

"Look at the Murphy buildings, then

look at our other buildings," says one

SEBCO maintenance man. "We know how

to take care of buildings when we are

given the stuff we need."

A friend of Gigante, also speaking on

condition of anonymity, says the priest is

fed up with NYCHA's requirement that he

pre-clear repairs totaling more than

$1 ,500."They want to do privatization, but

they don' t want to give the contractor the

freedom to run the buildings like he wants

to," the source says.

Publicly, however, NYCHAdenies any

conflict. "With SEBCO we really don't

have any problem with their maintenance.

We' ve had a few complaints on their

paperwork, but that's all," says NYCHA's

Gross. "But bear in mind, this is a pilot ini-

tiative .... And these buildings were a dis-

aster before SEBCO took them over."

If Gross chalks some of the complaints

up to the contract's novelty, he sees a more

nefarious potential source: SEBCO's

aggressi ve rent collection efforts.

"Is it not possible that suddenly there's

a new regime here, a regime that's collect-

ing rent more vigorously than before, that

maybe there's a feeling among the tenants

that, hey, SEBCO's screwing us?" he asks.

Still, lawyers from the Legal Aid

Society are considering filing a c1ass-

action lawsuit against SEBCO, NYCHA-

or both-on behalf of Mattie Roberts and

other tenants.

For the time being, Mrs. Roberts seems

resigned to a bathless future. "I don't com-

plain," she says. "I just keep paying my

rent and hoping. "

CITY LIMITS

YES! Start my subscription to City Limits.

City Limits shows you what is

working in our communities:

where the real successes are

taking place, who is behind them,

why they're working and what we

can all learn from them. And we

expose the bureaucratic garbage,

sloppy supervision and pure

o $25/one year 00 issues)

o $35/two years

Business / Government/Libraries

o $35/one year 0 $50 two years

Name

Address

City State Zip

City Limits, 40 Prince Street, New York

10012

GUTSY.

corruption that's failing our

neighborhoods. City Limits: News.

INCISIVE.

Analysis. Investigative reports.

Isn't it time you subscribed?

FEBRUARY 1997

PBOVOCATIV I;.

mBankers1rust Cotnpany

Community Development Group

A resource for the non-profit

development community

Gary Hattem, Managing Director

Amy Brusiloff, Vice President

280 Park Avenue, 19West

New York, New York 10017

Tel: Fax:

Me

PIPEliNE ~

,

-

New Lords of Flatbush

Immigrants are an economic powerhouse rescuing long-

neglected New York neighborhoods. By Sasha Abramsky

M

un Cha sits in the storage

area beneath his large deli

on Church Avenue in

F1atbush, Brooklyn, talk-

ing about his experiences

in America. Upstairs, dozens of customers

buy a hybrid mix of Caribbean fruits and

vegetables and Korean delicacies. A buck-

etful of blue crabs sits on the floor, not far

from shelves stocking Worcester and soy

sauces. In the surrounding neighborhood

are stores owned by other Koreans, as well

as Arabs, Indians, Mexicans, Caribbeans

and a plethora of other nationals. Flatbush

has become one of the great crossroads of

the world.

In Korea, Mun also worked in a shop,

but says he couldn't earn much money

there. His sister lived in Chicago, and in

1982 he decided to join her. "My brother-

in-law's older brother had a business in

New York. We called him. He said, ' New

York's got many jobs, but it's very hard. '"

Mun and his wife decided they would take

a chance, and moved to Brooklyn to live

with his brother-in-Iaw's relatives. Mun

cleaned fish at a local fish market and his

wife worked in a fruit market. He worked

12 hour days, six days a week for $250,

learning English from the customers.

In five years Mun managed to save

enough capital to open his own store in

Crown Heights: "No babies, no time for

spending money. How to spend money

when you're working twelve hours?!" he

explains, as if justifying himself. He rent-

ed a house on Ocean Avenue, and, in 1991,

bought the deli that he runs today.

Mun and his wife have three young

children now. He's hoping they will one

day go to college. He says he fmally feels

like he may have succeeded, that he may

have actually "made it" in America. But

life still isn't easy. "Still working hard!" he

laughs. "But it's better than before. The

business is bigger, I make more money.

But I'm still working hard. We have to go

to market in the early morning, at four or

five o'clock, five days a week: Hunts Point

Market and Brooklyn Terminal Market.

We're just making money for living."

Mor. than Half a MI llion

As Mun Cha contemplates success, a

new generation of immigrants is once again

defining the character of New York City. In

the I 990s, newcomers have been arriving at

a faster pace than at any time since the

1920s, more than 112,000 a year according

to the Department of City Planning. More

than half a million immigrants made new

homes here between 1990 and 1994, and as

of 1995, fully one-third of the city's popu-

lation had been born in another country.

While the immigrant tide generates

controversy across most of the United

States, it generates economic might in

New York's neighborhoods. Despite all the

misleading rhetoric about immigrants as a

ball and chain dragging down America-

and despite new federal laws making them

ineligible for major social programs

including welfare and food stamps-

immigrants have become the middle class

backbone of long struggling New York

communities.

More than half of the male immigrants to

the city in the early 1990s, and nearly two-

thirds of the female immigrants, were either

white-collar professionals or skilled work-

ers' according to ''The Newest New Yorkers,

1990-1994," a report released by the city

planning department last month. The largest

numbers have come from the Dominican

Republic, China, the former Soviet Union,

Jamaica and the tiny South American coun-

try of Guyana.

After nearly two decades of a steady

influx of such people, neighborhoods like

Brooklyn's Flatbush boast a more highly

educated population and a higher rate of

homeownership than many neighborhoods

populated primarily by native-born

Americans. The trend has become even

more pronounced since the federal

Immigration Act of 1990 created a pool of

140,000 visas per year exclusively reserved

for professionals and skilled laborers.

Professor Emanuel Tobier, a senior

research associate at New York

University'S Taub Urban Research Center

who is studying the role of immigrants in

the labor force, has calculated that as of the

1990 census, 9.8 percent of New York

City'S foreign-born population was self-

employed, compared to 8.4 percent of

those born in America.

And only two percent of non-refugee

immigrants of working age reported

receiving welfare throughout the I 980s,

compared with 3.7 percent of the home-

grown population, according to the Urban

Institute's 1994 report, "Immigration and

Immigrants." Excluding refugees, immi-

grants' use of welfare actually fell in the

1980s. Whatever their reasons for avoid-

ing the dole, the evidence is strong that

immigrants are more likely than native-

born Americans to be economically

mobile, quickly driving up their personal

incomes after moving to the city.

Most Ethnically Dlv.rs.

Nowhere is the impact of the recent

waves of immigration clearer than in

F1atbush, home of the most ethnically

diverse zip code in the country. Flatbush

and Church avenues are a jumble of

Korean, Indian, Middle Eastern, Haitian,

Jamaican, even Mexican businesses. The

customers reflect the same diversity.

The neighborhood' s ethnic composi-

tion has changed drastically over the last

two decades. According to census figures

for Community District 14, more than half

of the area's residents were white in 1980

and about one-third were black, most of

them born in the United States. Fifteen

years ago, long stretches of the neighbor-

hood's commercial strips were vacant.

Most of the middle class whites and

blacks living east of Flatbush Avenue

were departing for the suburbs or other

neighborhoods.

By 1990 30,000 West Indians had

moved into the district, along with thou-

sands of Africans and Haitians-as well as

approximately 1,500 Arabs. In the early

1990s, the trend continued with more than

10,000 new immigrants from Jamaica,

Haiti, Guyana and Trinidad. By 1993, out

of a total population of 153,000, more than

60 percent were foreign-born. That same

year, the neighboring district of East

F1atbush was 71 percent foreign-born.

"Immigration has just really turned

around this area," says Carol Lutger, who

runs the Business Outreach Center of the

Church Avenue Merchants and Block

Association (CAMBA). "The stores are

full, the rents are high, there's so much

street activity, there's a tremendous variety

of stores. Because it's crowded on the

streets, people feel safe."

Like Mun Cha, many immigrants

arrive in America determined to buy their

own businesses and houses as soon as pos-

sible, researchers say. "Neighborhood

rejuvenation requires entrepreneurship,"

CITY LIMITS

2

Tobier explains. "The newcomers rejuve-

nated those communities by starting busi-

nesses, buying up property." To that end,

family members often pool their savings

with other immigrants who have joined

together into informal credit associ a-

tions-"Susus," "Box," or "Partners" in

the Caribbean communities, "Kehs" in the

Korean-which help members make

downpayments on homes and businesses.

In Flatbush, according to the city's

1993 Housing and Vacancy Survey, nearly

one in four households owns

their home. In East Flatbush,

the rate is one in three. Rates

are similar in several other

neighborhoods where immi-

grants are a majority: In

Sunset Park, close to 30 per-

cent are homeowners; in

Flushing, more than 44 per-

cent; in Jamaica, Queens, the

figure is above 40 percent and

in Jackson Heights, it is 35

percent. And trends suggest

these figures are rising.

Although no studies have

determined how much money

circulates through the rotating

credit bodies, at least two

major banks-Chase and

Republic-now consider

"susu" membership a valuable

qualification In deciding

whether to approve mortgage

applications.

The recovery in Flatbush

has been nurtured by a net-

work of business groups,

community centers and immigrant-aid

agencies established over the course of

the past two decades. Organizations such

as CAMBA, the Flatbush Development

Corporation (FDC) and the Caribbean-

American Chamber of Commerce and

Industry (CACCI) offer language cours-

es and legal services to immigrants, pro-

vide health-care information and social

services, and help would-be entrepre-

neurs develop business plans. They also

channel small-scale loans to new

Americans to help them set up their

businesses. Staff members counsel

locals, helping them through business

problems and potential cultural misun-

derstandings. And they arrange meetings

designed to bring together representa-

tives from the various nationalities pre-

sent in the area.

The economic expansion within the

community feeds on itself, explains Dan

Schachter of the FOe. "Part of the cor-

poration's role is to create that transition

FEBRUARY 1997

point so that when immigrants have

saved enough they don't go to New

Jersey, but buy from our existing housing

stock."

The average age of immigrants at the

time they arrive in New York, according

to the new city planning report, is barely

27. "They're in their prime working and

child-bearing years," says Frank Vardy,

one of the authors of the report. "They

patronize family stores that didn't exist in

old neighborhoods" before they arrived.

Immigrant Mlddl. Cia

The 1993 Housing and Vacancy Survey

also found that in Flatbush, 24,039 resi-

dents had sixteen or more years of educa-

tion-making the district one of the most

well-educated communities in Brooklyn.

In many immigrant populations, more than

30 percent of the arrivals have college

degrees, says Tobier. "And when you're

talking about Indians, it's 40 to 45percent.

The [educated immigrants] may not all be

professionals here, but they do all right

economically."

Lesley Jules, a 31-year-old Haitian

artist, uses his education to run a translation

agency out of the second floor of one of the

late-Victorian, colonnaded mansions that

serve as beautiful reminders of a time when

Flatbush was a suburban outpost of the

city. The floors are varnished wood, the

walls adorned with several of Jules' pas-

toral interpretations of Haiti 's countryside.

A dapper man wearing a well-tailored

suit and a flowered tie, Jules has lived in

the United States since his departure from

Port-au-Prince in 1982. Two years ago,

with a partner, he invested $9,000 in

advertising spots and other publicity, and

started up a company, Jins Incorporated.

The firm now has 75 translators and inter-

preters available on call. They charge flat

rates to corporate clients, less to immi-

grants who come seeking help. It is a suc-

cessful enterprise, but after the overhead,

Jules says, he is left with less than $4,000

a month to split with his partner.

Nevertheless, he considers himself part of

the immigrant middle class.

Jules is scornful of the notion that

immigrants come to America to live off the

country's welfare system. In his experi-

ence he has found that immigrants, even

when they are near-penniless, are general-

ly reluctant to apply for public help.

"When someone is an immigrant, the

first thing in your mind is, this country

gives you a lot of opportunity. You always

know what you left, in what situation you

were in." And as hard as New York can be,

he says, it's got more to offer financially

than most immigrants' home towns. "You

have to fight for it," he adds.

Then he remarks on his personal moti-

vation: "I want it. It'll take me time, but

what I want, I'll get. I don't care how long

it takes me to reach my goal. I'm going to

be a success."

Sasha Abramsky is a Manhattan-based

freelance writer.

Immigramsfrom all

over the world shop

along Church

Avenue ill Flatbush.

Brooklyn.

-

'-. ---- here's a new type of Latin King," insists Hector Torres.

"A whole new flavor. But the cops want to insist it's the

same old thing." Among many young people in the

Bronx and Harlem, Torres, 39, has become known as

"the Ambassador." He is a former gang leader-at age 14,

in the I 970s, he was president of the Notorious

Bachelors-but in recent years he has negotiated

between factions in the sub-worlds of New York City youth culture.

"My role is to keep in touch with the different nations in this

city," Torres says, referring to the mostly underground, gang-

structured organizations of the Almighty Latin King and Queen

Nation, the Zulu Nation, the Five Percent Nation, and the Netas.

Hi s current mission is to lead the Latin Kings away from the drugs

and violence their name has come to symbolize.

These photographs were taken at a "Universal ," the monthly

meeting of the Latin Kings held on January 6th, Three Kings Day.

About 1,000 Latin Kings attended the holiday celebration at St.

Mary's Episcopal Church in Harlem, hosted by Father Luis

Barrios.

Six weeks earlier, a federal jury had convicted the Latin Kings'

former leader, Luis Felipe, of arranging the brutal murders of rival

gang leaders. Felipe reportedly founded the New York chapter of

the Latin Kings 10 years ago in an upstate prison.

Yet even as scores of gang members attended Felipe's trial and

CITY LIMITS

religiously protested hi s innocence, they insisted that the Latin

Kings' criminal days were behind them. For more than a year the

group has worked with the National Congress for Puerto Rican

Ri ghts to help on a campaign against police brutality, and at last

year's Puerto Rican Day Parade, the Kings, Netas and Zulus

marched with Housing Works and gave out 10,000 free condoms.

According to Torres, pictured above in the photo on the right

with his hands crossed, the young Latin Kings are largely misun-

derstood. The Kings were once "violent, very violent," he admits,

but he says that today most of the old guard is either dead or in jail.

"Of course, we have elements that are no good and we deal with it

when it comes up," he reasons. "Say you have three sons, one is in

FEBRUARY 1997

trouble a lot, one is in school doing well , and the other is back and

forth between the two. That is [true in] many families. You could

say the same thing about the Boy Scouts or any college fraternity."

The police say the Kings continue to be a criminal street gang, and

have accused them of masterminding the recent sniper shooting of a

Bronx police captain. Torres counters that the charges smack of COIN-

TELPRO-style defamation, blanting the Kings for a range of crimes in

retributi on for the groups's campaign against police brutality.

"When journalists come and see with their owns eyes what we

do, the work with clergy, the leadership seminars the kids have par-

ticipated in, they can't believe it," says Torres. "These kids have

open hearts. This is about love, not gangsterism."-Kiema Mayo

-

-

Name a poweiful special interest in New York that doesn't have a political action committee.

''What are you getting SO pushy forr' snarls the woman behind

the counter of the State Board of Elections office in Albany.

"Excuse mer'

She grabs the stack of papers from my band, SCWTies away to have them photocopied, and then, upon returniDg,

throws them onto my desk, a good five foot toss.

Welcome to the warm, hospitable world of New York's political action committees, better known as PACs. The offense

I bad been a.c:cnsed of-being "pushy"--c:onsisted of driving the three-hour, snowy, rainy trek to the state capital to

peruse the dozen or so file cabinets that contain the financial disclosures of all the state's PACs.

To find out about PACs-fnndraising orpnizations which exert huge inOuence over state and city politics-you have to

travel to AJbany. The state legislature has resisted computerizatiou for more than a decade, ri{fging the regulations so

that supposedly public information is held closely under the watchful gaze of patronage hires from the Republican and

Democratic party orpnizations. The employees in the basement of the capital complex office building, where the files

are stored, are notoriously hostile, not unlike trained glJard d. Earlier in the day, they berated me for not putting the

paper clips back on the reports properly. No wonder the place was empty.

A PAC, for those who don't know, is the political wing of a corporation, union, industry association or advocacy group.

I. RBNT STABILIZATION

ASSOCIATION PAC

t Issa.s. Gutting rent control and rent stabilization.

Pavorlt. poUUclaaa: State Senate

Republicans, Rudy Giuliani, Fernando Ferrer,

the Conservative Party.

With the state legislature preparing to debate

the renewal of rent regulations this spring, the

Rent Stabilization Association (RSA) takes the

mantle of New York City's most powerful

PAC. It has plowed $700,000 into the

campaign treasuries of State Senate

Majority Leader Joe Bruno and his GOP

sidekicks, and helped prime the pump

for hundreds of thousands of added dol-

lars in donations from indi vidual land-

lords. And while RSA can't muster the

foot soldiers that major union-run PACs

usually produce, its leadership has

proven itself to be exceptionally crafty.

As a result, the organization is in a

better position now than at any time

in the last two decades to achieve

its once-unthinkable goal: abolish-

ing New York's rent regulations.

RSA PAC has grown consider-

ably over the past four years; it

barely squeaked into the Top 10 contributors in 1993. But that was

before Joe Strasburg, the current RSA president and strategist,

came along with the extensive political contacts he'd garnered in

his days as Council Speaker Peter Vallone's top aide. As landlords

lobbed $125,000 to elected officials from the city, Strasburg cob-

bled together coalitions not only of Republicans, but of black and

Latino Democrats willing to support landlord legislation (see

"Wedge City," City Limits, January 1997). While many of these

politicians are unwilling to speak publicly in favor of abolishing

rent protections, they have already shown quiet support for

changes such as decontrol of high-priced rentals. And they've

sponsored RSA-backed legislation that would require tenants in

Housing Court to make up-front deposits of unpaid rent.

In 1996, RSA PAC donated almost $250,000 to state politi-

cians, in addition to $284,416 from its sister Neighborhood

Preservation PAC. RSA also poured $50,000 into a new low-key

landlord PAC set up in September (see sidebar).

For the 1996 state elections, RSA PAC's biggest contributions

went to the state Senate GOP and the tiny but influential

Conservative Party ($75,000 over the last year and half). Mayor

Giuliani is a landlord favorite ($7,700, the maximum for a may-

oral candidate), as is Bronx Borough President and mayoral can-

didate Fernando Ferrer ($7,500). But these numbers don't tell

most of the story. Big landlords associated with RSA-Lenny

Litwin and Jeffrey Manocherian, to name two--channel their

money to RSA-friendly candidates, as do major law finns, man-

agement companies and contractors. RSA PAC also works on

Illustrations by Aaron Meshon CITY LIMITS

You can't. As the city's election year gets undefWay, we take a look at the top ten. By James Bradley

PACs can dispense money and help coordinate election campaigns. They make direct contributions to other PACs and

to candidates, up to the limits prescribed by law. But PACs, unlike corporations, can also give an unlimited amount of

money to Democratic or Republican party organizations. The organizations, in turn, can pour the casb-"soft money"-into

the campaigns of their choice. It's a loophole that gives PACs far more punch than they appear to have under the law.

While in some states the power of PACs has begun to be eclipsed by more creative routes around finance laws, in

New York, PACs remain the political battering ram of choice for the rich, powerful and, yes, the truly pushy.

Try to name a single group with a reputation as a political force in New York that doesn't have a PAC. You can't.

Politicians may not want reporters to have easy access to the dollar amounts on the filing forms, but the PACs them-

selves want their power to be well known. A million bucks in the bank is important, but cultivating an image as a mns-

cular player is the key to getting your way in New York politics.

"A PAC sends a message," says Norman Adler, a lobbyist and consultant who has founded some of New York's most

important PACs (two of which are on the following list). "Even though all the check has on it is the name of the PAC, the

amount and the signature, it's as if a thousand words are written on it. And those words say: 'We're an important fon:e.'"

With that in mind, City Limits has compiled an accurate, if largely unscientific, list of the most powerful political

action committees that influence politics and policymaking. Money was an important factor in rankings, but not the only

one. This is a power-rating guide, attuned to an organization's ability to influence decisionma.kers, make or break elect-

ed officials and, of course, project the image of a political titan.