Professional Documents

Culture Documents

City Limits Magazine, February 1998 Issue

Uploaded by

City Limits (New York)Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

City Limits Magazine, February 1998 Issue

Uploaded by

City Limits (New York)Copyright:

Available Formats

Progressive Prospects

l

n a city of roughly 7.3 million people and more than 3.5 million voters,

only 757,564 men and women elected our mayor last November. Instead of

reflecting on these numbers as a saddening commentary on our electoral system,

think of it as an opportunity for renewing progressive politics in New York.

Giuliani won fewer votes than any sitting mayor since the 1920s. There's no deny-

-_ .... --... "'.-

ing the man's popularity in lower Manhattan, Staten Island

and eastern Queens. But the guy simply has not got the viscer-

al appeal of a widely popular politician. At this point it doesn't

EDITORIAL

look like anyone else in his business does, either.

Why? Because Neither Giuliani nor Governor Pataki nor

their opponents have addressed many of the issues that really

hit home for low- and moderate-income working people. The

politicians claim they represent us law-abiding citizens in

their fight against the darker forces of society----and when it

comes to busting crack dealers and gun runners, they do. But what else are they

doing for the regular hard-working New Yorker?

Living standards are slipping. Studies reported in this space last month indicate

that the city's middle class is shrinking fast and wages have fallen significantly since

the 1980s. Meanwhile, CUNY enrollment is down. The city has drastically scaled

back enforcement of the housing code and, more significantly, is investing little capi-

tal in housing rehabilitation. Much of the public infrastructure is a mess, schools

worst of all. More than 300 pedestrians were killed by cars last year. Poverty rates

are rising---an estimated 1.95 million New Yorkers had annual incomes below the

poverty line in 1996. And make no mistake: poverty is a quality of life issue. Squalor

remains a very public condition throughout the five boroughs.

OK, so I've painted a bleak picture. Yet what I've described is a city that desper-

ately needs leadership on issues beyond the fight against crime-leadership on

issues that touch home. Encourage wage growth, shore up the middle class, attack

poverty where it lives, invest in schools and housing, make this city a comfortable

place to live for everyone who wants to work for it, and an easier place to do busi-

ness for the small companies that employ most of our workforce. Promote opportu-

nity---it's the winning word, but in local politics these days, it's hardly ever heard.

Pollsters nationwide report that politicians who address such elemental issues

are winning electoral majorities. Yet no New York candidate for mayor, governor or

senator has been selling such a populist progressive message. Who are they speaking

to? Not the majority of New Yorkers, who are too turned off to vote.

***

A correction: Last month in our "Ammo" section, we misidentified the organiza-

tion that oversees the South Bronx section of the city's Empowerment Zone. It is the

Bronx Overall Economic Development Corporation----not the South Bronx Overall

Economic Development Corporation (a.k.a. SOBRO). The latter is a nonprofit com-

munity group, while the former is an arm of the borough president's office.

Andrew White

Editor

Cover photo of children at the lifeline Center by Mayita Mendez

City Limits relies on the generous support of its readers and advertisers. as well as the following funders: The Robert Sterling Clark

Foundation. The Unitarian Universalist Veatch Program at Shelter Rock. The Edna McConnell Clark Foundation. The Joyce Mertz

Gilmore Foundation. The Scherman Foundation. The North Star Fund. J.P. Morgan & Co. Incorporated. The Booth Ferris Foundation.

The Annie E. Casey Foundation. The New York Foundation. The Taconic Foundation. M& T Bank. Citibank. and Chase Manhattan Bank.

-

City Limits

Volume XXIII Number 2

City Limits is published ten times per year. monthly except

bi-monthly issues in June/July and August/September. by

the City Limits Community Information Service. Inc . a non-

profit organization devoted to disseminating information

concerning neighborhood revitalization.

Editor: Andrew White

Senior Editors: Kim Nauer. Glenn Thrush

Managing Editor: Carl Vogel

Associate Editor: Kemba Johnson

Contributing Editor: James Bradley

Interns: Joe Gould. Jason Stipp

Design Direction: James Conrad. Paul V. Leone

Advertising Representative: John Ullmann

Proofreader: Sandy Socolar

Photographers: Melissa Cooperman. Martin Josefski

Mayita Mendez

Associate Director.

Center for an Urban Future: Neil Kleiman

Board of Directors':

Eddie Bautista. New York Lawyers for

the Public Interest

Beverly Cheuvront. Girl Scout Council of Greater NY

Shawn Dove. Rheedlen Centers

Francine Justa, Neighborhood Housing Selvices

Errol Louis

Rebecca Reich, LlSC

Andrew Reicher, UHAB

Tom Robbins, Joumalist

Celia Irvine, ANHD

Pete Williams, National Urban League

"Affiliations for identification only.

Sponsors:

Pratt Institute Center for Community

and Environmental Development

Urban Homesteading Assistance Board

Subscription rates are: for individuals and community

groups, $25/0ne Year, $39/Two Years: for businesses,

foundations, banks, government agencies and libraries,

$35/0ne Year, $50/Two Years. Low income, unemployed,

$10/0ne Year.

City Limits welcomes comments and article contributions.

Please include a stamped, self-addressed envelope for retum

manuscripts. Material in City Limits does not necessarily

reflect the opinion of the sponsoring organizations. Send

correspondence to: City Limits, 120 Wall Street, 20th FI. ,

New York, NY 10005. Postmaster. Send address changes to

City Limits, 120 Wall Street, 20th Fl., New York, NY 10005.

Periodical postage paid

New York, NY 10001

City Limits IISSN 0199-03301

(21214793344

FAX (2121344-6457

e-mail : CL@citylimits.org

On the Web: www.citylimits.org

Copyright 1998. All Rights Reserved. No

portion or portions of this journal may be reprinted with-

out the express permission of the publishers.

City Limits is indexed in the Alternative Press

Index and the Avery Index to Architectural

Periodicals and is available on microfilm from University

Microfilms International, Ann Arbor, MI 48106.

CITVLlMITS

FEBRUARY 1998

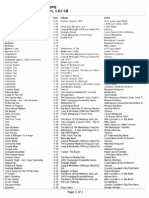

FEATURES

Trouble in Mind

Medicaid managed care is just around the bend for tens of thousands of

New York's emotionally disturbed children. That much is certain. What's

unknown is who will be covered-and what will be lost. By Glenn Thrush

Broken Homes

Nearly hidden within 20 acres of emptied public housing projects in the

poorest part of Newark, the Friendly Fuld Head Start Center proves that

appearances can deceive. By Helen M. Stummer

PROFILES

UPROSE Blooms in Brooklyn ~

A Sunset Park community group found a way to survive city budget cuts, but

can it bring unity to a fragmented neighborhood? By Kemba Johnson

A Shot in the Arm

Harm reduction is being redefined by the volunteers of Streetwise Health

Project, who bring health care to people who have gone without for far too long.

By Dylan Foley

PIPELINES

Mixing the Message KfJIII

Welfare advocates said they dreaded the expansion of WEP in the nonprofit

sphere. According to the latest city contract, they might not have to worry.

By Carl Vogel

Scoppetta's Home Stretch ~

ACS Commissioner Nicholas Scoppetta has unveiled his promised plan to

move the child welfare system back to the grassroots. The next step is paying

for it. By Atlam Fifield

Review

Placing the Blame

Cityview

Go Get Oem Votes

Spare Change

Mayoral Mad Libs

Editorial

Briefs

Ammo

COMMENTARY

129

By Kirk Vandersall

130

By Ron Hayduk

134

By Carl Vogel

DEPARTMENTS

2 Professional

Directory 32, 33

5-7

Job Ads 32, 33, 35

31

-

of

NEW YORK

INCORPORATED

Your

Neighborhood

Housing

Insurance

Specialist

-

BankersTrust Company

Community Development Group

A resource for the non-profit

development community

Gary Hattem, Managing Director

Amy Brusiloff, Vice President

130 Liberty Street

10th Floor

New York, New York 10006

Tel: 2122507118 Fax: 2122508552

For 20Years

We've Been There

ForYou.

R &F OF NEW Y ORK, INC. has a special

department obtaining and servicing insurance for

tenants, low-income co- ops and not-for-profit

community groups. We have developed competitive

insurance programs based on a careful evaluation

of the special needs of our customers. We have

been a leader from the start and are dedicated to

the people of New York City.

For Information call:

Ingrid Kamins ki. Executive Vice President

R&F of New York

One Wall Street Court

New York, NY 10005-3302

212 269-8080 800 635-6002 212 269- 8112 (fax)

New York

Lawyers

for the

Public

Interest

provides free legal referrals for

community-based and nonprofit groups

seeking pro bono representation.

Projects include corporate, tax

and real estate work, zoning advice, housing

and employment discrimination,

environmental justice,

disability and civil rights.

For further information,

call NYLPI at

(212) 727-2270.

There is no charge

for NYLPI's services.

CITY LIMITS

Jazz Scene

Basie's

Band Gets

Union Gig

T

erence Conley remembers a night

two years ago when he had to stand at

an ATM to take money out of his sav-

ings account to pay the other mem-

bers of his jazz trio after a bar owner

shortchanged them. "A local musician has to

fight to get his money at the end of the night,"

Conley says. "You still have to pay the guys."

As a pianist in the Count Basie Orchestra, fill-

ing the musical shoes of His Highness himself for

the last two years, Conley no longer has to worry

about getting what's owed him. And now he

doesn't have to worry about how he'll pay the

bills once the music stops, either. Last fall, the

19-piece orchestra became the first unionized big

band. "We didn't look to be unionized," he

admits. "We were looking for a pension."

In fact, the unionization was a simple, harmo-

nious improvisation worthy of the Basie name.

After management fired a 20-year veteran, the

members began to talk about the sting of not hav-

ing pension benefits. By joining Local 802 of the

American Federation of Musicians, they can join

the union's $1.2 billion pension pool.

And senior bandmembers like Bill Hughes,

who has played trombone in the group for 38

years, can now stretch their legs in business class

during the orchestra's four annual overseas flights.

Other agreement terms limit the amount of time

the band, which is on the road 34 to 40 weeks

every year, can travel on performance days.

It's benefits like these that usually make man-

agers view unionization as costly agony. But for

Aaron A. Woodward ill, CEO and president of

Count Basie Enterprises, who has struggled to

preserve the band after Basie's death, it was a

godsend. "It's difficult to retain good musicians,"

Woodward says. "In the fourteen years Count

Basie has not been with us, it's been difficult to

keep them together."

Local 802 isn't going to take five after

adding the Basie band to their rolls. The union

has started a "Justice for Jazz Artists" cam-

paign. "There are a few bands out there that I

FEBRUARY 1998

think are ripe for unionization," notes union

president William Moriarty. Jazz musicians his-

torically aren't as well protected as Broadway

or symphonic musicians-and many former

members of touring bands have ended up living

in severe poverty in their later years. The Jazz

Foundation, a charity that assists musicians, has :.;;;

thrown several benefits to raise enough money J

to lay some fine jazz musicians in their final ~

'

resting place. -Kemba Johnson :!

w

Briem .......... ------.......... --------------

s

Labor

Union Boss

Backs Bad

Boy Devona

I

t was no shock when Gus Bevona, the pro-

fusely paid and notoriously autocratic boss

of the building services union, appealed a

sweeping court decision on his local's elec-

tion. The surprise came when Brian

Mclaughlin, head of the mainstream New York

City Central Labor Council, rushed in with support.

On December 15, Federal Judge Richard Owen

found that Bevona-who pays himself $494,000 a

year to run Local 32B-32J-"suppressed dissent"

and trampled on members' rights in an early 1997

election. Union critics documented many abuses

during the vote: leadership recommendations

printed on ballots, unmonitored ballot boxes, and

polling hours that excluded many of the union's

55,000 mostly minority workers.

In addition to electing union reps, the members

were voting on proposed bylaw changes that

would have reduced officers' swollen salaries and

guaranteed that members would have the right to

approve contracts. In his ruling, Owen wrote that

the union's members will suffer "an enormous risk

of abuse of power by the incumbent leadership"

unless future votes are conducted by outsiders.

Mclaughlin, a Democratic Queens assembly-

man and former electrical union official, instruct-

ed attorneys at his 500-union umbrella Central

Labor Council to join in the appeal against the

decision, arguing that the court dangerously

exceeded its authority. "[Owen's] orders threaten

to fundamentally interfere with internal union vot-

ing policies and the right of unions to self-gov-

ern," CLC chief counsel Douglas Menagh wrote

to labor attorneys in a bid for support.

The decision to join the appeal was not a popu-

lar one, even among lawyers affiliated with the

council. Only 12 of the 69 members of the council's

own lawyers' advisory committee agreed to the

appeal.

For their part, the anti-Bevona dissenters,

who garnered 45 percent of the vote last time,

were stunned by the council's decision. "We

proved at trial that members of our union were

openly coerced," says Carlos Guzman, leader of

32B-32J's dissident Members for a Better Union.

"Brian McLaughlin, who wants to be mayor,

should align himself with the rank and ftle he is

supposed to be speaking for. "

-Michael Hirsch

Swimming with sharks?

Many non profits are developing important business relationships

with corporations and government agencies. These efforts can

help non profits to expand or improve services and reach more

constituents.

Establishing business relationships requires many special legal

skills, from handling negotiations to preparing contracts.

Lawyers Alliance for New York staff and volunteer attorneys are

experts in helping to structure business relationships for non-

profit clients. To find out more about how Lawyers Alliance can

help nonprofits take advantage of new business opportunities,

call us at 212-219-1800.

99 Hudson Street

New York, NY 10013

212219-1800

Lawyers Alliance

for New York

Building a Better New York

Ambition

Housing PIan

FneIsLopez

Election Bid

B

rooklynite Vito Lopez tells City

Limits he is leaning toward a run for

Congress this fall. And to kick things

off, the head of the state Assembly's

housing committee has unveiled an

ambitious plan to increase the state's spending on

housing from $115.6 million to $297.6 million.

Full acceptance of the $11l2 million package

isn't likely from either Governor George Pataki or

Lopez ally Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver. Still,

Democratic party sources say Silver will probably

bargain for some of its elements during budget

talks later this year. The list includes plans to:

boost the state Low Income Housing Trust Fund

from $25 to $60 million.

double the state's contribution to homeless hous-

ing from $30 million to $60 million.

create a state version of the federal low-income

housing tax credit program, which gives tax

breaks for developers who build rental housing for

the indigent and working poor.

inaugurate a $25 million anti-abandonment pro-

gram to preserve apartment buildings in disrepair.

Much of that money would go to local groups for

housing organizing.

increase funding for the Affordable Home Own-

ership program from $25 million to $60 million.

"I believe Shelly [Silver] will support a good

portion of this," Lopez says. "If we don't get it this

year, we're never going to get it." Silver's office

did not respond to inquiries about the plan.

Lopez told City Limits he is seriously consider-

ing a 1998 challenge of BrookJyn Congresswoman

Nydia Velazquez. ''There's a good chance. I'll

decide by the end of this month," he says.

'1t is our practice not to comment on candidates

who just say they might run," says Velazquez

spokesman Eric Brown. -Glenn Thrush

WEEKLY UPDATES NEW YORK

For a first gtimp;e at our BriefS, try City

limits Weekly, a free fax and e-mail rt!SOUJ'Ce

for anyone who needs to keep on top of

what's happeniDg aaoss New York-fromjob

opportunities to late-breaking news. To be

aAIded to our fist, just call 212-479-3348, fax

212-344-6457 or e-mail c1@cityIimits.org

CITY LIMITS

...... ----------....

ffiMilllli THANA SCHEDULEg !t.:::I1

= FOUR LOWCOST, TO NEW YORK CITY'S= y iiiiIII

==

BIGGER BATHROOMS . ALTERNATE YEAR INSTRUCTION

I'

DOORMEN

City Contracts

Brooklyn

Bias Charge

in AIDS

Ftmding

M

ore than two dozen Brooklyn

organizations found themselves

left out of a $41 million funding

package in November, virtually

ensuring that their community-

based AIDS programs will be shut down at the

end of February. Last month, the city announced

it had found another $5 million to disburse-but

that hasn't placated the Brooklyn organizations.

''This is basically a plan where federal money

is being shifted from programs that serve people

of color to white people," charges Carol Horwitz,

a lawyer at the Brooklyn Legal Services

Corporation A, whose group was left off the

FEBRUARY 1998

CLASS CONSOLIDATION

November list. In 1997, her organization received

$105,000 in federal Ryan White Care Act Title I

funding to provide services for people with HIV

ranging from custody planning to representation

in eviction proceedings.

According to Horwitz, 75 percent of the fed-

eral funding that formally went to Brooklyn com-

munity-based organizations was moved to

Manhattan-based groups like the Gay Men's

Health Crisis. The Mayor's Planning Council on

mY/AIDS had mandated that the funds be grant-

ed to geographically appropriate CBOs with a

long history of serving their communities.

The nonprofit Medical and Health Research

Association of New York (MHRA)-which had

been contracted by the city to disburse the $41

million in Ryan White funds for 1998-received

more than 500 proposals, giving the'green light to

172 programs from 103 agencies. The 25 defund-

ed Brooklyn organizations include two of the

three Haitian-run AIDS programs in Brooklyn and

nine out of 10 support groups serving AIDS suf-

ferers and their families in Crown Heights,

Brownsville and East New York.

"Seventy percent of new AIDS cases are in

the outer boroughs," says Abigail Hunter of the

WilliamsburglGreenpointlBushwick HIV Care

Network, one of three Brooklyn umbrella

groups for community-based HIV organiza-

tions. "The planning council directive of giving

more money to local CBOs was meant to

address the situation. The present funding has

done the opposite."

"The 1998 contracts are based on extremely

objective criteria set up by the city's Ryan White

Planning Council, the state AIDS Institute and the

federal government," counters Fred Winter, a

spokesman for the city's Department of Health.

"Citywide contracts are given out because of

economies of scale. There is a finite amount of

money available, and there are always w0rthy

programs that won't be funded."

However, Barbara Turk of MHRA's HIV Care

says $5 million in additional Ryan White funding

will soon be made available for 1998: $2.4 million

for case management and $2.6 million for treat-

ment, education and client advocacy. She says her

organization will go back to the list of applicants

to award additional grants.

''The $2.6 million set aside for critical gaps in

services does not in any way make up for the

money cut in Brooklyn," Horwitz responds.

Hunter adds, that once the funds have been allo-

cated to 17 different categories, there is only

$131,000 for food and nutrition programs city-

wide-and merely $41,000 for support groups.

"That's not enough for one program," she says,

"let alone programs citywide." The coalitions are

asking the mayor's office to stop contract nego-

tiations with the grantees and extend 1997 fund-

ing until the new grants are reviewed.

-Dylan Foley

UPROSE Blooms

Brooklyn

In

PROFILE ' k

.. _-...."...1; Li e many small organizations, one of Sunset Park's oldest

Executive Director

Elizabeth

Yeampierre says

UPROSE works

to build unity in

a neighborhood

that is ethllically

fragmented.

__ .. :M_

community groups has lost city funding--and is building

a new agenda. By Kemba Johnson

S

unset Park's matriarchs and patri-

archs enter a modest Fourth

Avenue storefront with bag lunch-

es in hand and questions in mind.

They come to UPROSE, a com-

munity organization that has served the

Brooklyn neighborhood for 32 years, to

learn about changes in welfare and immi-

gration laws or to have official letters trans-

lated into Spanish. They stay to talk about

their children and their community.

"They feed their children. They dress

them. They try to set a good example,"

says Elizabeth Yeampierre, UPROSE's

executive director. "But then [the kids]

drop out or start hanging out in the street."

Puerto Rican, Dominican, Cuban-the

men and women sit in the office, eat their

lunches and fmd some common ground in

a neighborhood that has seen precious lit-

tie of it over the last few years.

Michelle De La Uz, director of con-

stituency services for neighborhood

Congresswoman Nydia Velazquez, says

these residents have grown up with the

organization helping their families. "I call

them repeat customers," she says. "They

say, 'You helped my mother, you helped

my daughter. Now you can help me.'''

In addition to assisting immigrants in

navigating the welfare system, UPROSE is

working in local schools to help troubled

kids. The group is also building a base of

political activism against the state's plan to

rebuild the Gowanus Expressway and re-

route traffic down the community's

avenues. Yeampierre says all of UPROSE's

work has another underlying component as

well: building unity among the communi-

ty's fragmented ethnic enclaves.

Despite its deep roots, however,

UPROSE has been through hard times of

late, weakened by inconsistent leadership-

and by the loss of city funding that has hit

scores of similar small neighborhood orga-

nizations over the last few years. An inde-

pendent study published by the Arete

Corporation in October found that more

than half of all small nonprofits that held

city contracts when David Dinkins left City

Hall have since lost their funding. UPROSE

is part of that disinvested majority.

Ethnic T.nslons

Fifth Avenue is Sunset Park's outdoor

living room. Pizzerias compete with

Mexican fast-food taqueritas. Dominican

and Puerto Rican flags label the ubiquitous

car services. And shoppers in the discount

stores spill onto the sidewalk, as young peo-

ple stake their claim to street corners.

UPROSE has served this neighborhood

since 1966, founded by Puerto Rican

activists to support newcomers to what

had been a mostly Scandanavian commu-

nity. The United Puerto Rican

Organization of Sunset Park and

Education Services, as it was called, pro-

vided day care, after-school programs and

assistance with welfare and other benefits.

Recently, the group bowed to the

neighborhood's changing demographics

by dropping its full name and adopting the

acronym, UPROSE. Sunset Park's Latino

population is now a turbulent array of eth-

nicities-and the neighborhood's long-

established Asian community is growing

quickly as well. Ethnic tensions occasion-

ally flare into open violence: Three Latino

teenagers beat and nearly killed a Chinese

man last August. Police say it was a bias

crime.

"What weakens [the community's]

political presence is a lack of unity," says

Yeampierre, who took charge of the orga-

nization in 1996. "We really do have issues

in common: immigration, education,

sweatshops and bilingual education."

Keeping the racial and ethnic tensions at

bay has become part of the directive for

UPROSE and a personal mission for

Yeampierre, who hopes a new focus on

political activism can pull Sunset Park

together.

Surmounting Chall.ng.s

Two years ago, it was unclear whether

UPROSE would even survive. During a

six-month leadership vacuum before

Yeampierre's arrival, the group failed to

file reports on city-funded projects and

didn't even start a contracted program to

teach English as a Second Language. We

were in a very precarious position," says

Juan Beritan, UPROSE's board chairman.

Ten days after Yeampierre became

executive director, the city's Community

Development Agency, which had provided

$40,000 to run the ESL program and pro-

vide information about entitlements, can-

celed its contract.

"The tImIng was consistent.

Organizations of color-aided by the

CITY LIMITS

Giuliani administration-were disappear-

ing all over the city," Yeampierre says.

"The city's shift [away from the smaller

community groups) occurred just as the

organization was not running as tightly as

it should have been. It may have been

only $40,000, but it made a big difference

in how we were able to function."

UPROSE now depends on volunteers

to help local residents with public assis-

tance. The group relies on money from the

United Way and other private sources to

sustain its budget, and no longer runs

after-school or day care programs.

But UPROSE still maintains its pres-

ence in three area high schools and one

junior high school, where its five staffers

work. In stay-in-school programs at each

school, 30 or so students considered at risk

of dropping out learn about activism and

ethnic tolerance-and study their academ-

ic subjects. ''We never lose sight of our

objectives to teach them to read, write and

be good in math," says Yeampierre, a for-

mer civil rights attorney. "Once they know

how to do that, they can take charge of

themselves and their community."

Teresita Rivera-Neri, UPROSE's pro-

gram counselor at John Jay High School in

neighboring Park Slope, noticed students

carving out Puerto Rican, Dominican and

other enclaves in the lunchroom and class-

rooms. So she started a Latino Club, where

students read literature and perform dances

from all over Latin America.

"They suddenly fmd themselves in a

new country," Rivera-Neri explains.

''There's a fear of the unknown. In class

they'll say, 'I'm better than you,' or 'My

country is better than yours.' [The Latino

Club) really helps them to realize they

have so much in common."

One of the things all the residents of

Sunset Park have in common is the pro-

posed $700 million reconstruction of

Gowanus Expressway. UPROSE is edu-

cating residents about the potential health

threats of the construction and re-routed

traffic. The neighborhood already is

stricken with the third highest asthma rate

in the city.

The group is organizing residents and

pushing for a comprehensive study of

alternatives such as building a tunnel to

replace the Gowanus. Lucy Lopez-a for-

mer Work Experience Program worker and

a mother of three-lives two blocks from

the expressway with a 7-year-old asthmat-

ic son. With UPROSE's help she's begun

speaking out. "With all the pollution,

how's every child who lives in the com-

munity going to stay healthy?" she asks.

FEBRUARY 1998

All th. Chang

Despite the organization's state of tran-

sition, women and men from the neigh-

borhood still file into the office looking for

advice and company. "I don't have the

sense that the community knows all the

changes we've gone through," Yeampierre

says.

Still, the troubles have had conse-

quences. "In small community agencies

like that, if the board isn't constantly

fundraising or there's no development

component, their projects last as long as

1998

SOCIALIST

SCHOLARS

the money lasts," says Sister Mary

Geraldine of the Center for Family Life,

another neighborhood organization that

has served the neighborhood for 20 years.

"Yet [UPROSE is) still around, committed

to the community."

Preparing for the future, Yeampierre

hopes to hire an Asian tutor for UPROSE's

school programs and set up workshops to

teach residents how to advocate and get

answers from the city for themselves.

"UPROSE is here to stay," she says.

"We're here to be reckoned with."

March 20th through 22nd 1998

Borough of Manhattan Community College

199 Chambers Street

For more information, call (212) 642-2826

or visit http://www.soc.qc.edu/ssc

Mailing Address:

Socialist Scholars Conference

c/o CUNY Graduate Center

CONFERENCE

33 West 42 Street, NY NY 10036

Email: socialist.conf@usa.net

Specializing in

Community Development Groups,

HDFCs and Non--Profits

Low ... Cost Insurance and Quality Service.

NANCY HARDY

Insurance Broker

Over 20 Years of Experience.

270 North Avenue, New Rochelle, NY 10801

-

PROFILE

Karyn London

(right), a physi-

cian's assistant

who volunteers

for Streetside,

checks in with

one of her

regular patients

at an Upper West

SideSRO.

(.M

A Shot in the Arm

In the name of harm reduction, Streetside Health Project volunteers provide health care in

some of city's overlooked corners. By Dylan Foley

B

rendan Pearse sits in the back

of the Lower East Side Needle

Exchange's Avenue C store-

front on arainy November

night, giving free flu shots to a

steady stream of squatter kids and intra-

venous drug users.

Pearse, a physician's assistant in his

early 50s, demonstrates how to administer

injections for the three New York

University medical students he's supervis-

ing. "Make sure you clean the skin before

you inject," he says gently to one, who is

clearly nervous. A bleached blond woman

waiting nearby breaks the tension as her

sleeve is rolled up, joking about the horri-

ble nicknames she had in high school.

The next woman in line is worried-

she talks in hushed tones about chronic

medical problems, including diarrhea that

has gone on for months. Concerned she

might have the symptoms of tuberculosis,

Pearse examines her with his stethoscope.

He decides it isn't TB after all but urges her

to go to a local clinic near her home in

Hartford, nonetheless.

Pearse is here as a member of the

Streetside Health Project, a small volunteer

medical program that has been serving intra-

venous drug users in Manhattan, Brooklyn

and the Bronx for six years. The operation

may be modest-it consists of a handful of

medical professionals and a tiny budget-

but it represents what may be the ultimate

form of "harm reduction," the HIV-preven-

tion strategy that includes giving clean nee-

dles to addicts.

Streetside's volunteers bring inocula-

tions and quick medical exams to needle

exchanges, soup kitchens and SROs that

house people with AIDS. Sometimes they

make house calls to bandage abscesses or

treat thrush, an oral fungus common in

AIDS sufferers. Streetside was the ftrst

medical group in New York to vaccinate at

the needle exchanges and still is the only

group that provides medical care in some

privately run SROs.

Crudglngly ACC.ptH

Harm reduction has only recently

become a grudgingly accepted practice.

illegal needle exchanges appeared in New

York in the late 1980s, supported by radical

groups like ACT-UP. But in 1992, after

several years of conflict with the police and

City Hall, several exchanges were given

wai vers by the state to distribute clean

syringes. That year, a group of medical res-

idents at the Bronx's Montefiore Hospital

and Sharon Stancliff, a family practice doc-

tor volunteering for the Lower East Side

Needle Exchange, formed Streetside.

"Our major goal is to show people who

use drugs that they can do something about

their health care," Stancliff says. "We also

try to introduce health-care professionals

and future health-care professionals to peo-

ple they would normally see only in

adverse situations."

The program now has a core group of

eight doctors, nurses and physician's assis-

tants, volunteering their time, and actively

recruits students at New York-area medical

schools to lend a hand. In December, a vol-

unteer pool that had swelled to 40 complet-

ed Streetside's fall vaccination program,

dispensing 600 flu vaccinations and 200

inoculations for bacterial pneumonia,

which is often fatal to people with HIV.

"The fall vaccination program is our major

CITY LIMITS

&

group project. At other times, members do

volunteer outreach on their own," says Dr.

Toni Sturm, one of Streetside's founders

who is now a medical fellow at Mt. Sinai

Hospital in Manhattan.

The approach has found other adher-

ents. For example, New York Harm

Reduction Educators, a needle exchange

that serves the Bronx and Harlem, is visit-

ed by a medical outreach van from Bronx-

Lebanon Hospital. Many of the existing

exchanges have become community-based

organizations that also offer support

groups, drug treatment and even acupunc-

ture to help clients. The goal is simple:

Prevent the spread of HIV through clean

needles and condoms, as well as education

about safe sex and safer drug use.

The population at the needle exchanges

and SROs needs all the help it can get. Less

than half of the 150 clients Streetside sur-

veyed in 1996 had any regular health care.

Another survey showed that many of the

clients lodged in three Manhattan SROs

were not taking the new protease inhibitors

used to fight AIDS. In response, Streetside

held a workshop on the drug therapy cock-

tails and continues to advocate their effec-

tiveness to clients.

Committed Activists

Streetside's work has attracted some of

the most low-key but committed harm

reduction activists in the city-a real-

world, traveling cast of ER without the

makeup or a chance to reshoot the scene.

"I joined Streetside because it was one

of the few preventive programs I could

find," says Pearse, who became a physi-

cian's assistant two years ago after spend-

ing 10 years working as a paralegal. A

native of Northern Ireland-his father was

one of the founders of the Irish Communist

Party-Pearse obtained his green card by

fighting with the U.S. Marines in Vietnam,

including combat at the infamous Battle of

Kbe Sanh in 1967.

Pearse grew up in Derry, a strife-tom,

impoverished Catholic city directly affect-

ed by Protestant-Catholic hatreds. "When I

was a kid, the only people not destroying

things were doctors, nurses and teachers,"

he says. "I became a physician's assistant

to do good, provide relief and empower

with knowledge."

Four years ago, Karyn London left the

feminist bookstore she founded to become

a physician's assistant. Today, she works at

the Ryan Community Health Center on the

Upper West Side and regularly visits three

nearby SROs as a member of Streetside.

Her rapport with the residents translates

into an effective approach on issues like the

FEBRUARY 1998

Streetside's work attracts some of the most low-key

activists in the city-a real-world, traveling cast of ER

without the makeup or a chance to reshoot the scene.

new AIDS treatment. "I try to engage them

on the subject," she says. 'They trust me

more than the people in white coats."

On a bitterly cold Saturday, London

walks through the Camden Hotel in the

West 90s with a nurse and a premedical

student. In the forbidding maze of hallways

with musty carpets, London's style is infor-

mal and coaxing. "C'mon, open up," she

cajoles, rapping on the doors of her regu-

lars. "It's me, Karyn."

An intense woman with a head of gray

hair, London admits she often goes to the

hotels more than once a week to look in on

her most worrisome cases. 'There is a

degree of intimacy with the flu shot-

sticking someone takes time, and it is an

excellent way to get to know them," she

explains with a chuckle. She adds that the

shots also provide an opportunity to dis-

cuss other health problems.

Some of London's patients begin to

emerge. A frail woman in her mid-60s

injured her foot trying to remove a corn, and

it has become badly infected. Pleased by the

attention of the visit, which alleviates the

loneliness of her tiny room, she chats on

while London takes her temperature.

Down the hall, a very sick transgender

woman with long brown hair hurries to one

of the bathrooms-she hasn't been to a

health clinic for more than two years. "She

has the same problems that people with a

history of drug use have-she does not have

the skills for navigating the system,"

London says. "People also have an addition-

al hostili ty because they can't determine her

sex." Health-care hurdles like these aren't

covered in med school, but they're not

uncommon for Streetside's volunteers.

By way of example, London tells of a

patient named Frank, an elderly man suffer-

ing from AIDS-related dementia. The con-

dition made him easy prey for other resi-

dents in the hotel, who would rob him when

he went on drug binges. For months, she

tried to get him to move into St. Mary's, a

skilled nursing residence for people with

AIDS. But when he finally went for an

interview, he politely refused to move in,

saying he didn't like the tea they served.

Insurance Barriers

Streetside's 1997 budget was a minus-

cule $5,000, donated by two of the

group's members. The Department of

Health provided the flu shots for free as

part of its vaccination program, but the

bacterial pneumonia vaccinations cost

$10 apiece. Some medical supplies like

disposable thermometers and bandages,

have to be bought; others are donated.

Streetside is fueled by volunteer labor,

of which it seems there is never enough.

"I think we'd be eligible for various

grants, but before we obtain money we

really need more medical volunteers

first," Stancliff says. The biggest obstacle

is malpractice insurance. "The insurance

from their regular jobs does not usually

cover volunteer medical activities," she

explains. "It really is a low-risk situation,

however. Studies have shown that poor

people are very unlikely to sue."

Still, expansion plans are moving

along. "We've had requests from a soup

kitchen in the Bronx to provide more basic

medical care, and we are planning to set up

a volunteer medical project with one of the

needle exchanges on the Lower East Side.

We also want to start giving Hepatitis B

vaccinations," Stancliff says.

Much of the work they do is simply

filling the gaps left by an indifferent

health care bureaucracy. At the privately

owned AIDS-housing SROs, caseworkers

from the city's Health Department should

be carrying much of the load, but a source

familiar with the hotels says the workers

aren't always dependable: "Some are con-

scientious, and some are appalling. The

SRO owners provide the office space for

the social workers, and this dependency

hurts their ability to advocate for their

clients."

And so London says her sickest clients

will often put off calling 911 for days, until

she can take them to the hospital. Such is

the level of trust she has built among peo-

ple to whom trust comes hard.

"Often their previous experiences

receiving health care have been degrading

and negative," she says. 'They don't want

to go through the system alone. Who

would?"

Dylan Foley is afreelance writer in

BrookLyn who volunteered for the Lower

East Side Needle Exchange in the early

199Os.

-,

Mixing the Message

PIPEliNE i

,

A new city contract confounds conventional wisdom

on nonprofit workfare. By Carl Vogel

I

t's hard to decide which is more

surprising: what changed or what

remained the same. When city offi-

cials announced guidelines for a

new set of nonprofit workfare con-

tracts in January, they stepped up pres-

sure on contractors to find welfare recip-

ients real, paying jobs. But anticipated

plans to pour thousands of workfare

assignments into the nonprofit sector

aren't materializing.

Both developments are welcome news

Giuliani introduced his new HRA chief

Jason Turner to the City Hall press

corps-officials outlined details of the

nonprofit workfare plan. To the surprise

of most everyone outside the agency,

HRA announced that the contracts-

which begin in July-will be limited to

300 assignments each, an overall reduc-

tion of 100 nonprofit workfare slots city-

wide.

"I thought they were going to increase

the number massively," says Peter

IIMaybe a year from now we'll kick ourselves

for not multiplying the level of workers. "

If-

for welfare-rights advocates, who have

criticized the Giuliani administration for

failing to help welfare recipients find

decent employment. Still, the nonprofits

and the mayor's critics alike are left won-

dering what this new contract means for

the city's planned expansion of the con-

troversial Work Experience Program

(WEP).

Nonprofit Shar.

The majority of New York's 35,000 to

38,000 workfare slots are in city agencies

and include everything from picking up

trash for the Parks Department to clerical

work in local hospitals. The city's Human

Resources Administration (HRA), which

runs the workfare program, won't say

how many people have been assigned to

workfare. But over the course of a year, a

given slot can be filled by several differ-

ent workers, as participants find a real

job, suffer sanctions for failing to comply

with the program, or decide to abandon

their welfare check.

Since 1994, six nonprofit agencies

have managed a total of 3,400 WEP slots,

generally outsourcing most assignments

to other community groups, where the

workers do clerical, maintenance and

community service duties. Last month,

those agencies had to join others in bid-

ding for 11 new contracts spanning the

next three years.

At a January 7 meeting with nonprof-

its-held at the exact same time as Mayor

Swords, executive director of the

Nonprofit Coordinating Committee,

echoing many others who follow the

workfare program. As some observers

note, the timing of the meeting was sym-

bolic: This plan is the swan song of for-

mer HRA Commissioner Lilliam Barrios-

Paoli, who told the City Council last

spring that her agency expected to add

10,000 WEP assignments. She had led

observers to believe a large number of

these would be with nonprofits, and many

neighborhood and religious groups

mounted an anti-WEP campaign to con-

vince non profits not to cooperate.

HRA says the new arrangement sim-

ply allows for a wider array of approach-

es to handling the workfare program.

"Maybe a year from now we'll kick our-

selves for not multiplying the level of

workers," says Seth Diamond, deputy

commissioner at HRA' s Office of

Employment Services. "But we don't

want to overextend ourselves."

A close look at the numbers shows

why the city might be able to avoid the

nonprofit expansion. According to the

Independent Budget Office, in May

1997-the latest month available-a total

of 2,202 WEP workers were assigned to

nonprofits. That's only 65 percent of the

current contracts' capacity.

Furthermore, pressure to meet federal

work requirement goals isn't as intense as

many had thought. While the city's own

numbers are widely disputed, the state as

a whole has achieved the necessary per-

centage of eligible public assistance

recipients in work activities-at least for

the time being. And if there are fewer

people on the welfare rolls in the future,

meeting the federal requirements gets

easier.

P.rlormanc. Bas.cl

For the agencies that do sign up to run

WEP slots, the rules have changed. The

11 agencies will be handed a more

demanding contract than the one signed

in 1994. Every year, each contractor will

have to fmd paying jobs for at least 75

welfare recipients-or lose some of its

funding. But there is a carrot along with

that stick: Nearly half of the contract's

potential payout is tied to finding WEP

workers employment outside the welfare

system.

HRA will pay in the neighborhood of

$125,000 annually to each of the contract

agencies. In addition, they will earn

$1,000 for each of their workfare partici-

pants who secures a full-time, paying job

for at least 90 days, up to an annual ceil-

ing of $115,000.

While the city required contract agen-

cies to report on job placement in the

past, there was no fmancial incentive.

Vicki Cusare, director of the Italian

American Civil Rights League, which has

managed 1,200 workfare assignments for

the city since July 1994, says her group

has always kept up with the workers after

they left WEP for employment. But she

admits the new performance-based con-

tract will require more paperwork. Other

nonprofit executives say they won't go

after the new contract because the money

is insufficient.

"We recognize we're asking for a

lean and efficient program," Diamond

says. The city insists the targets can be

met, however. Apparently, some non-

profits agree. More than a few agency

representatives at the HRA meeting said

they would send in a proposal by the

January 30 deadline.

Cusare also says her agency is going

to reapply, but she might have been more

shocked than most when the city spelled

out the rules. The January meeting was

the first indication her organization

would be limited to 300 assignments.

"We were surprised. We have more par-

ticipants than that," she says. "I guess

we'll have to cut a lot of sites out."

CITY LIMITS

s

Scoppetta's Home Stretch

The child welfare system lurches back to the neighborhoods. By Adam Fifield

F

or Nicholas Scoppetta, it was a

promise a long time in coming.

Standing on stage at the

Salvation Army's 14th Street

headquarters last month, work-

ing a room jammed with skeptics, the

city's child welfare commissioner said he

would accomplish what none of his prede-

cessors could. He intended to reform a sys-

tem where 85 percent of the city's foster

care children are removed from their

parents and placed in distant communi-

ties, far from their family, friends,

schools and everything they have known

growing up. He would bring the child

protection business back into the neigh-

borhoods.

His plan-which has been on the

drafting board at the Administration for

Children's Services (ACS) for more than

a year-would force a retooling of the

entire child welfare system. The city

would require that all services to families

and children, including foster care, fami-

ly counseling, mental health care and

much more, be provided close to horne

whenever possible.

Scoppetta also proposed an added

responsibility for foster parents. In an ini-

tiative dubbed "Family to Family," foster

parents would be required to work with a

child's birth parents "before, during and

after placement," serving as mentors and

dealing closely with ACS caseworkers to

create a "community of care" for the child.

"I can't help but think that what we are

setting out to do is of truly historical pro-

portions," Scoppetta told his audience of

social service and foster care providers. "It

is truly going to be a radical change."

Lacking Vital Contacts

People who work in the field have long

argued that the city's ultra-centralized

child welfare system makes little sense.

ACS caseworkers are often unfamiliar

with the communities and lack vital con-

tacts in places like schools, churches and

block associations. Social service agencies

contracted to help troubled families are

frequently located in remote neighbor-

hoods, invisible to overwhelmed parents

who might voluntarily seek help. And

when children are placed miles away from

their homes, parents have trouble visiting

them and working with counselors-dras-

FEBRUARY 1998

tically slowing the reunification process.

Few in the field are openly criticizing

the philosophy behind Scoppetta's ambi-

tious initiative. In fact many describe it as

"visionary" and even "revolutionary." But

they do have concerns about the details.

The draft plan Scoppetta released in late

November does not delineate how the tran-

sition to his new system will be funded or

implemented, how eXlStmg community

resources will be used, or how ACS itself

will recast its bureaucracy to playa role in

a supposedly more collaborative, support-

ive and creative child welfare system.

And the multimillion dollar nonprofit

foster care organizations with city contracts

are not yet buying into the plan. The indus-

try is suffering from sharp cuts in state

funding imposed two years ago, explains

Fred Brancato, executive director of the

Council of Family and Child Caring

Agencies (COFCCA), a foster care indus-

try trade group. If there is no new money,"

he says, "to try to respond to [Scoppetta's

plan] seems to be beyond what an agency

can do."

Resistance to change from within the

system-and a paucity of political

willpower at City Hall-have repeatedly

stymied similar reforms. As early as 1971,

the Citizens' Committee for Children

issued a report emphasizing that child

welfare services should be stationed in

neighborhoods where most of the affected

families live. A half dozen mayoral com-

missions and studies since have made sim-

ilar recommendations. None of them have

generated significant reforms.

Given the historical context, it's easy to

understand why some providers are cynical

about Scoppetta's chances for success. "All

of it sounds never-never land, like a fairy

tale," says Jane Barrowitz, spokesperson

for the Jewish Child Care Association of

New York.

But Mayor Rudolph Giuliani appointed

Scoppetta in February 1996 with a mandate

to rebuild the system and, as an old friend

of the mayor, the commissioner has more

political support than his predecessors.

Does that mean he can also muster

fmancial resources for the restructuring?

Insiders say a significant up-front invest-

ment will be needed to revamp agencies so

they can better train foster parents and

staff, open new neighborhood offices,

recruit local boarding homes and build last-

ing networks with other community-based

service providers. In the long run, they add,

the new system should save money by

PIPELINE i

,

Advocates of

community-based

services. including

John Sanchez of the

East Side

Settlement House.

want to prevent

ACS reformfrom

pushing aside

minority-run

organizations.

Me

shortening the length of time children stay

in foster care. But this will take some time.

"We support innovation," says COFCCA

spokesperson Edith Holzer. "But we can't

do it in a kneeling position. We don't see

how you can attempt the reforms in the

commissioner's plan without bringing the

foster care system back up to adequate

funding. " In 1995, Governor George

Pataki signed block grant legislation

reducing child welfare funding to the city

by $131 million. The city's foster care

agencies, group home providers and foster

parents are all receiving lower reimburse-

ments these days, Holzer says.

City Limits asked Scoppetta where the

money for his plan would come from.

"Costs will have to be addressed," he said.

He did not, however, offer any details.

Independent Endowments

Some of the more innovative child

welfare non profits say this money crunch

shouldn' t undercut Scoppetta's reforms,

however. "I feel that money could be

much better spent than it is now," says

Sister Mary Paul Janchill, cofounder of

the Center for Family Life, a Brooklyn

agency providing a variety of services to

the Sunset Park community. "We have a

huge amount spent on foster care and

child welfare, and neighborhood-based

foster care is not more expensive."

Smaller, community-based providers

do have major concerns, though. They fear

Extended Family

Scoppetta's plan will, paradoxically, favor

the city's big, centralized foster care agen-

cies at the expense of organizations deeply

rooted in the neighborhoods.

Most of the larger organizations are

based in religious institutions and have

independent endowments. They can better

afford to make the investment in addition-

al services and training, notes John

Sanchez, executive director of the East

Side Settlement House, which provides

family support services to parents in the

Mott Haven section of the Bronx.

Scoppetta's plan could encourage them to

become heavyweight players in low-

income neighborhoods where smaller,

minority-run agencies are located.

To comply with Scoppetta's mandate,

the big agencies may look to merge with

neighborhood-based agencies or push

them out of the picture, inheriting their

valuable base of families. Stephen

Chin1und, executive director of Episcopal

Social Services, drew loud applause from

the packed Salvation Army auditorium

when he asked Scoppetta's deputy com-

missioners how agencies like his could be

expected to compete. "The agencies that

will suffer the most from this are those

closest to what you are calling for. " None

of the five ACS staffers responded.

"I do have a level of trust about where

Scoppetta is coming from," adds Sanchez.

"But too often, these efforts are grafted onto

these communities without any knowledge

T

he Family To Family component of Scoppetta's plan would require foster parents to

serve as mentors for a child's natural parents. Advocates say it is on target philo-

sophically-but there are some very big obstacles.

"Foster parents create a lot of friction with the bio parents," argues Edward Richardson,

a single father who lost and regained custody of his four children. "Ninety percent of the

time, foster parents would rather keep the child than release the child." Richardson is a

parent advocate at Bronx Family Central, a neighborhood-based family support agency

founded jOintly by two non profits, St. Christopher-Jennie Clarkson and Episcopal Social

Services.

He and his fellow parent advocates are firm believers in their own form of mentoring:

They work closely with parents who have children in the system, helping them maneuver

through court, social service bureaucracies, drug rehab and other programs.

But in Brooklyn's Sunset Park, the Center for Family Life has long since established a sys-

tem in which foster parents have a responsibility to work closely with a child's family, help-

ing them achieve stability and learn parenting skills.

"We will not license any foster parent who is not going to be part of the work toward

reunification," says the organization's cofounder, Sister Mary Paul Janchill. "There have been

many foster parents who have worked very well with birth parents. It is a task of working

together, of partnering, that occurs with the support of a good foster care agency."-AF

- - ~ ! ....

of what's going on." The commissioner

should build ground rules into the plan that

will protect well-run, homegrown agencies,

he says. Otherwise, ACS may well lose the

important local connections these groups

have cultivated over the years.

''This is first and foremost a business,"

says one former city child welfare official

who asked not to be identified. He predicts

that in 10 to 15 years, the city's communi-

ty-based network will consist of a few

monolithic foster care agencies. "There are

larger forces at play than good will and

good intentions," he warns.

Close Connections

Even setting aside power politics and

money, there are also different sides to the

argument that foster children should be

placed close to home. As Scoppetta

explains, 80 percent of children taken into

the city's care ultimately return to their

family. Therefore it behooves the city to

maintain close connections between the

child and his parents or relatives.

But there are times when children need

distance. "If you take them out of the com-

munity, you don't have to worry about

peer pressure and they can start to get

help," says Matthew Matgranow, a 21-

year-old who spent 10 years in foster care

living in a half-dozen different neighbor-

hoods. ''The whole issue, in the long run,

is what's better for them."

Ultimately, it is the rights-and the

lives-of children and families that are at

issue. Gail Nayowith, executive director of

the Citizens' Committee for Children,

emphasizes that Scoppetta is headed in the

right direction. But she is calling for

changes at ACS as well. Staff must be bet-

ter trained, the agency must do more to

educate parents about support programs

and officials should set up a complaint

bureau for children, parents and foster par-

ents who feel mistreated, she says.

''The scope of change that is being pro-

posed is huge and the stakes are high," she

says. "We have to proceed with the maxi-

mum amount of intelligence."

As City Limits went to press, ACS offi-

cials were honing the final plan. The

agency is expected to start seeking formal

bids for new contracts this spring.

"If we wait for total agreement, we will

never get the system to where it needs to

be," Scoppetta told his audience at the

Salvation Army. Then he took a pause for

emphasis: "It will be better," he said, "than

anything we' ve had in the past."

Adam Fifield is afrequent contributor to

City Limits .

CITVLlMITS

,eli

................ .............. ................ .

,

t

Francisca Salce, a.k.a. Joe ..

taking care of making her

business rise at her store on

1121 St. Nicholas Avenue at

166th St. in Washington Heights.

CALL: CHASE COMMUNITY

DEVELOPMENT COMMERCIAL

LENDING 212-622-4248

Movi!tg

,":

the right direction

Joe's Pizza was irstJ:.Jot only did Francisca Salce

make a for her store with great

,- <. ::'t@tirs

tasfing pizza, she'Was the first recipient of a loan under

The Chase Community Development Group's Small

Retailers Lendin,g1;;Prograro.

The Sman . Program is a unique

Chase wfiose ptttpose is to expand access to

bank loans for hard to fiDance small businesses, par-

ticularly those loqated iJi lQw- and moderate-income

communities. .., ,;Z,o

This program made it possible for Ms. Salce to optain

a loan' to relocate her restaurant, renovate the new

space and still remain ... the neighborhood in which

she has built a successful business.

Which is just fine by Joe's Pizza's customers, who

swear by the dough.

: .......................... Community Development Group

CHASE. The right relationship is everything.

sM

1997 The Chase Manhattan Bank. Member FDIC.

What price are we willing to pay to save the

Camelia Flye has

managed to get her

14-year-old son the

care he needs.

Others may not be

so lucky once the

state moves fami-

lies on Medicaid to

managed care.

-

T

he eight-year-old boy

bounded into the stair-

well leading to the roof of

his Harlem school. A

hard-charging classroom

aide carne up from behind just as the boy,

distant and methodical, was pulling a

handful of his shirt towards a lighter that

had appeared in his other hand.

When the flint sparked, the aide

screamed so loudly the boy simply forgot

to set himself on fIre.

Camelia Flye remembers taking her

son horne from school that day on the

East Side subway, which was strange

because she lived across from the

Cathedral of St. John the Divine on the

West Side. She was too distraught to even

think about what she was doing. Before

she could consciously form a plan, the

pair sleepwalked themselves into the

emergency room at Mt. Sinai, the best

hospital Flye had ever heard of.

"The thing I remember is that he

asked the psychiatrist to come out and tell

me he was okay," says, sitting in an apart-

ment dominated by her son's basketball

trophies. "It absolutely shocked me. I

never heard him talk that way about me.

Then I realized how serious this all was."

Over the next few months, with

intensive therapy, rehabilitation and a

daily cupful of medication, the boy stabi-

lized. His unpredictable behavior-

which had already earned him placement

in special ed-subsided, and he eventual-

ly emerged from his medicinal stupor to

make a few friends. One of them was a

little girl around the same age who had

tried to fling herself off an apartment

building roof. Marta Nelson, Flye recalls,

"was beautiful and sweet" and as angelic

looking as her own son.

She tells her son's story calmly, but

when she thinks of Nelson and the other

children she saw in the hospitals, the ones

who tried to kill themselves, the tears roil

behind her glasses.

"They are little children," she says.

"What in the world do they have to worry

about?"

CITY LIMITS

city's most disturbed k i d s ~ By Glenn Thrush

FEBRUARY 1998 ~

Mental health care

executive Pasquale

DePetris sees

managed care as

an opportunity to

change a dysfunc-

tional system.

-

C

amelia Flye's son, now 14, has had his setbacks,

but he has progressed so well over the last few

years his teachers are talking seriously about tak-

ing him out of special ed and "main streaming" him

into regular academic classes when he becomes a

sophomore next year.

Marta Nelson, also 14, is sitting in juvenile lock-up await-

ing trial on second-degree murder charges.

Last November, Nelson, who in recent years has been

bounced between several foster home placements, hopped into a

cab with a 22-year-old friend, pulled out a handgun and put a bul-

let into the head of the Senegalese driver as he tried to escape.

The daily papers focused on the fact that both girls seemed to be

involved with the Bloods street gang, but to the people who knew

her, it was the sad culmination of a deeply troubled childhood.

"She was a very sick child," Flye says. "I pray to God they'll be

gentle with her. She needs help."

The lives of severely emotionally disturbed children are

fragile and their fates are unpredictable---especially if they hap-

pen to be poor. Mental health professionals have long known that

children like Marta Nelson are even more complicated to treat

than mentally ill adults because their lives can be profoundly

altered by the flawed institutions upon which they depend-fam-

ilies, schools, friends, social service agencies, even the criminal

justice system.

Yet for decades, the state- and federally-financed system

cobbled together to help these kids has devoted only a fraction of

the resources necessary to keep them out of hospitals and jails.

"We just recently opened a facility in the South Bronx," says

Pasquale DePetris, vice-president of Steinway Child and Family

Services, a multiservice mental health care agency based in Long

Island City, Queens. "I told my staff, 'The work you're doing

here is going to determine how many kids in this neighborhood

are going to wind up in that new juvenile correctional facility

they just built across the street.'

"I honestly believe the reason you see all these kids in jails

is because we' ve never received enough funding to really do our

job," he adds.

That job is about to get a lot harder. Later than most states,

New York is embarking on the road

toward moving its entire Medicaid popu-

lation into managed care-a process that

for most welfare recipients means being

placed in an HMO. Tucked into this plan

is a more dangerous experiment, a pro-

gram to move the state's poorest and most

severely disturbed children into managed

care.

The outlines of the new plan are still

very vague, but according to advocates

and providers who have been working

with Albany to come up with a new sys-

tem, it's clear that the final product will

be geared towards containing costs in an

HMO-style capitation system and keep-

ing each child's use of mental health ser-

vices to a bare minimum.

And City Limits has learned that the

new system will be designed to accom-

modate only 25,000 children statewide-

even though a coalition of mental health

providers estimates the real number of

emotionally disturbed children in New

York State eligible for Medicaid-funded

services to be about 120,000.

"It is a social experiment t1Je likes of which we have never

seen before," says DePetris, who has been part of the nonprofit

sector's planning process. "I hope this works."

The terms of the experiment will be dictated by Albany, but

its most volatile ingredients will be mixed together by local men-

ta! health organizations. This small, tightly knit community of

neighborhood-based providers has the expertise to design a new

system and will, quite possibly, form a network to administer the

entire end result.

But there's a catch. Resources will shrink-and that means

some local groups will need to change or face extinction.

"We already have a system that is dealing with only a frac-

tion of the kids that need to be served," says Suri Duitch, a staff

associate with the Citizens' Committee for Children, which has

organized an alliance of child mental health care providers to

shape managed care. "If kids aren' t using services, it's because

they can't get those services. We're talking about imposing man-

aged care on a system that's never even been managed before."

T

he motive behind reform is the explosion in med-

ical costs for the poor, an Old Faithful of red ink

that has nearly drowned the state's budget

throughout the 1990s. This year, Medicaid spend-

ing in New York State will reach $20.8 billion in

combined federal, state and city funding. In recent legisiati ve ses-

sions, Albany lawmakers didn't agree on much, but they did

agree to pass a series of bills mandating that all Medicaid recipi-

ents-including mentally ill kids-be moved into managed care.

Under the current and much-maligned "fee-for-service" sys-

tem, health care providers bill local Medicaid administrators for

each procedure they perform on covered patients. Traditionally,

government pays predetermined rates for each service, whether

it's a tooth extraction, open-heart surgery or a weekly therapy ses-

sion. Because more serious procedures are reimbursed at a higher

rate, professionals have a fmancial incentive to do work that

brings in the most money, even if it's not medically necessary. In

mental health care, the most expensive services are intensive day

treatment programs or residential placements, which can cost

CITY LIMITS

between $50,000 and $100,000 a year per patient.

The managed care model turns this system on its head. The

state will now identify a set dollar amount for the sum total of all

services and it will be up to whoever runs a specific managed

care plan to determine how those resources can best be allocated.

For child mental health, current Medicaid spending statewide is

about $350 million annually, according to Duitch. The total pool

of money under the managed care system is unlikely to be any

larger, and could, in fact, be smaller.

To explain how all this works, DePetris-a clinical psy-

chologist who also happens to have worked at Dun &

Bradstreet-sits at his conference table and draws a sweeping

bell curve, representing the distribution of people on Medicaid.

The bulge in the middle-the main body of the bell-represents

the bulk of people who will use services from time to time, typi-

cally once or twice a year. At the left margin of the chart-the

tapering edge of the bell-is a small number of people who never

go to the doctor at all. On the other end are chronic patients, the

relatively small number of people who, in managed care par-

lance, "over-use" services. DePetris circles this end of the chart.

"This is the key, " he says. "These are where your emotion-

ally disturbed kids fit. They need a lot more attention and money

than other people need. "

The 2.1 million members in New York's Medicaid system

include an extraordinary number of high-end users, many of

them chronically ill, elderly or severely disabled. Because of this,

abandoning the fee-for-service model poses problems: If the state

kept all of the high-end users in the large pool of Medicaid man-

aged care recipients, DePetris explains, they would siphon off too

many resources from more moderate users and force providers

into making across-the-board cutbacks that would affect every-

one in the system.

As New York and other states began planning their new

managed care systems, they started pressuring the Clinton admin-

istration to pull these high-use clients out of the mainstream

Medicaid population. The idea was to put them in their own sep-

arate system, so each client could be given a greater per capita

treatment package than standard Medicaid clients. The result has

been a flurry of 16 waivers granted by the

U.S. Department of Health and Human

Services, creating so-called "Special

Needs Plans," or SNPs- pronounced,

appropriately enough, "snips."

In July 1997, New York won federal

approval to create three such SNPs: one

for AlDSIHIV patients, another for adults

with mental illness, and a third for severe-

ly emotionally disturbed children. The

HlV and adult mental health SNPs are

currently being bid out to managed care

companies or networks of neighborhood-

based providers; they are expected to go

on-line within a year or so. But the child

mental health SNP will take at least one

more year to design because of its com-

plexity-and the fear of Marta Nelson-

type horror stories if kids fall between the

cracks. Even then, the new system will

begin slowly, in the form of several mod-

erately sized demonstration projects.

Yet if launching the SNPs has helped

solve a problem for the general Medicaid

population, it has created one massive

migraine for local providers.

FEBRUARY 1998

T

rying to make sense of a system whose complex-

ities are becoming increasingly brain-scrambling

even to professionals, DePetris clicks his pen