Professional Documents

Culture Documents

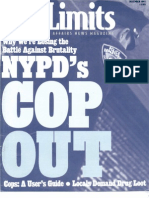

City Limits Magazine, April 2003 Issue

Uploaded by

City Limits (New York)Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

City Limits Magazine, April 2003 Issue

Uploaded by

City Limits (New York)Copyright:

Available Formats

AXIS OF EVIL: PRIEST, POLITIC1) STIFF HOMELESS, PAY GANG~

EDITORIAL

WAR GAMES

BY THE TIME YOU READ THIS, the massive anti-

war protests of February 15 may already be

replaying themselves, with thousands of

demonstrarors taking to the streets of New

York to show-again-their objections to the

war in Iraq. And perhaps, newly enlightened,

the Bloomberg administration will proceed this

time with respect and good sense.

But let's not count on it. The Bloomberg

administration, which has distinguished itself by

embracing rational responses to hot-button

political problems, made a disastrous miscalcula-

tion on February 15. The city's actions showed a

stunning lack of sensitivity to civil liberties, at a

time when citizens are already under siege from

Washington. Closer to home, the NYPD's exe-

crable handling of the hordes who turned our to

peacefully demonstrate also suggests-and not

for the first time-how out of touch Bloomberg's

City Hall is with the people it governs.

At 2 o'clock on Second Avenue at 65th

Street, as police trucks pulled up with fresh

reinforcements of cops and barricades, it was

embarrassingly clear that the officials running

this circus were not at all prepared for the mas-

Cover art and design by Noah Scalin, ALR Design

Centej for an

sive turnout. That can only be blamed on will-

ful ignorance. Protest organizer Leslie Cagan

once got 700,000 anti-nuke demonstrators

into Central Park. This time, the NYPD gave

her a permit for just 100,000, then forced

demonstrators to make mile-plus detours

through chaotic streets to get east to First

Avenue. Did they really just expect everyone

else to go home? Or not show up in the first

place? Apparently so.

Of course, there were other things on the

mayor's and Police Commissioner Ray Kelly's

minds when the NYPD went to court to demand

this travesty-to-be. A terrot watch that soon bled

from Yellow to Orange. The Republican Nation-

al Commitree, which wants to see that New York

will keep its convention next summer safe (and

not just from terrorists) . A devotion to labor-

intensive Giuliani-era public safety tactics, cou-

pled with the new need to keep police overtime to

a minimum. And for this post-partisan mayor, a

seeming distaste for political agendas in general.

Bur the city's decisions, which made the

NYPD the greatest threat to peace that day,

reflect a staggering blind spot. Just a year and a

half ago, New York experienced war for the

first time in centuries. How could the mayor of

New York City not recognize that many of the

people he governs are united by a revulsion

toward mass violence, born from their own

pain on September II? His city now also lives

with a genuine fear that war in Iraq may not

only fail to guarantee global safety but in fact

could have an escalating effect on terrorism.

For most of America, 9/11 was a reality TV

show. For many New Yorkers, it was an experi-

ence of solidarity with parts of the world that

have experienced out-of-control war-and

now want to stop their leaders from using vio-

lence as a tool for political or economic gain.

Mayor Bloomberg wants to stay above poli-

tics, but he stepped right into it when he strode

into office over the shards of September 11.

Whether he likes it or not, New York played a

tragic role in an emerging global conflict-and

a lot of us want the world to know that there's

more than one way to respond.

-Alyssa Katz

Editor

The Center for -an Urban Future

the sister organization of City Limits

www.nycfuture.org

F

Utroan

u ure

Combining City Limits' zest for investigative reporting with thorough policy

analysis, the Center for an Urban Future is regularly influencing New York's

decision makers with fact-driven studies about policy issues that are important to

all five boroughs and to New Yorkers of all socio-economic levels.

Go to our website or contact us to obtain any of our recent studies:

01 Labor Gains: How Union-Affiliated Training is Transforming New York's Workforce Landscape (March 2003)

01 Epidemic Neglect: How Weak Infrastructure and Lax Planning Hinder New York's Response to AIDS (February 2003)

01 The Creative Engine: How Arts and Culture are Fueling Growth in NYC's Neighborhoods (November 2002)

01 Bumpy Skies: JFK, laGuardia Fared Worse than most U.S. Airports after 9/11 and still Face Structural

Threats to Future Competitiveness (October 2002)

~ Uninvited Guests: Teens in New York City Foster Care (October 2002)

To obtain a report, get on our mailing list or sign up for our free e-mail policy updates,

contact Research Director Jonathan Bowles at jbowles@nycfuture.org or (212) 479-3347.

City Limits and the Center for an Urban Future rely on the generous support of their readers and advertisers, as well as the following funders: The Robert Sterling Clark Foundation, The Child

Welfare Fund, The Unitarian Universalist Veatch Program at Shelter Rock, Open Society Institute, The Joyce Mertz-Gilmore Foundation, The Scherman Foundaton, JPMorganChase, The Annie E. Casey

Foundation, The Booth Ferris Foundation, The New York Community Trust, The Taconic Foundation, The Rockefeller Foundation, The Ford Foundation, Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, The Ira W. DeCamp

Foundation, LlSC, Deutsche Bank, M& T Bank, The Citigroup Foundation, New York Foundation.

1

16 SHELTER GAMES

Secret ventures, cooked books and bail money for gang

members-it's all part of the seamy saga of a city homeless shelter

nonprofit now under federal scrutiny.

By Geoffrey Gray

SPECIAL REPORT

HOUSING: THE NEXT GENERATION

20 GREEN AND LEAN

A Harlem entrepreneur proves that housing can be

high quality, environmentally friendly-and affordable.

By Alex Ulam

22 MATERIAL WORLD

A California dreamer is determined to show New Yorkers that

reusing building materials will work.

By Hillary Rosner

25 HOUSING NEXT

What will Bloomberg's ambitious housing plan mean for New York's

poor? For community development groups? For your

neighborhood? The lowdown, in five parts.

By Matt Pacenza

CONTENTS

5 FRONTLINES: PEACE IN THE NEIGHBORHOODS ... PROJECT FIGHTER ... BRONX BOATHOUSE BUYER:

BEWARE ... A RECYCLING RACE .. NORTHERN MANHATTAN'S DISAPPEARING ACT ... HEY DUBYA: DUH!

11 OFF THE WATERFRONT

Soon after investing millions in upgrading Red Hook's port,

the city contemplates shutting down a successful shipping operation.

By Alyssa Katz

33 THE BIG IDEA

High school activists are fighting military recruitment, even though an

armed services job could be their peers' best shot at success.

By Kai Wright

APRIL 2003

36 CITY LIT

The Strike that Changed New York: Blacks, Whites and the Ocean

Hill-Brownsville Crisis, by Jerald E. Podair. Reviewed by Philip Kay.

39 MAKING CHANGE

Now that the West Village showed them the door, queer youth of

color are turning to drag houses for community.

By Kenyon Farrow

41 NYC INC.

Job trainers and their government funders should take a careful look

at the most successful employment prep groups out there: unions.

By David Jason Fischer

2 EDITORIAL 45 JOB ADS

47 PROFESSIONAL DIRECTORY

50 OFFICE OF THE CITY VISIONARY

3

LETTERS

SCABS!

Wendy Davis' puff piece on the Bronx

Defenders, "Keeping Close Counsel" Uanuary

2003]' buries the most salient fact about the

emergence of Giuliani's replacement attorneys

for striking Legal Aiders. Near the end Davis

finally writes, "When Legal Aid was the only

organized public defender, it used that power

to protect the rights of defendants." Here she

states the obvious: that Giuliani's splintering of

defense services was specifically designed to

weaken the voice of the indigent. Her mis-

placed adoration of the Bronx Defenders does

not change that essential reality.

The reality is that Bronx Defenders drains

precious resources by charging the taxpayers a

premium for defense services. Giuliani was will-

ing to pay that premium in his quest to break the

backs of strikers-and reduce the effectiveness of

public defense. When the current city adminis-

tration finally takes a close look at spending for

replacement attorneys, those dollars will be

removed from the indigent legal service budget.

What will remain is what Giuliani always

intended, a diminished public defense system

and a template for successful union busting.

The Association of Legal Aid Attorneys

(UAW 2325), a union Davis was once a mem-

ber of, carne into being to fight for basic due

process rights denied by New York City to any-

one unlucky enough to be arrested and poor.

The union struck and struck again, throughout

the 70s and 80s to preserve and enhance indi-

gent representation. Giuliani tried hard to

break our will and to prevent our existence. He

carne close to succeeding thanks to the over-

whelming good cheer and help he received

from the Bronx Defenders.

James A. Rogers

President

The Association of Legal Aid Attorneys

UAW2325

RIFE MATTERS

When I read stories so rife with insight and

multi-tiered factual detail, like "Why Minds

Matter," [March 2003] it's like the New Jour-

nalism is new again.

Greta Durr

National Conference of State Legislators

Education Program

ENERGIZED

Thanks so much for "Future Shock" [March

2003]' the excellent article about renewable

energy in New York. Like Alyssa Katz wrote in

her editorial, it's easy to feel hopeless when

faced with the problems of the city, particularly

these days, but there ARE some bright spots on

the horiwn!

Please keep us updated with any energy

developments.

Heather Floyd

"EI Barrio"

POWERFUL NUMBERS

I greatly enjoyed "Future Shock," by Mary-

Powel Thomas.

One sizeable error though: on page 40 she

says: "At the current average price of $1 0 a watt,

however, 2,000 megawatts of photovoltaic

energy would cost $20 trillion to install."

The $20 trillion figure is one thousand

times too large. Just do the math: 2,000

megawatts = 2 billion watts. Multiply by $10

per watt. The total is $20 billion. Still a large

sum, but not a hopelessly far out figure.

CLARIFICATION

Richard Perez

Research Professor

ASRC University at Albany

In our January 2003 review of Michael

Gecan's book Going Public, we should have

noted that the organization Gecan works for,

the Industrial Areas Foundation, and the group

reviewer Margaret Groarke is active in, the

Northwest Bronx Community and Clergy

Coalition, had a dispute in the mid-1980s over

areas of the Bronx in which both groups were

pursuing community organizing. City Limits

regrets the omission.

www.cityl imits.org

4

CITY LIMITS

Volume XXVIII Number 4

City Limits is published ten times per year, monthly except bi-

monthly issues in July/August and September/October, by City Lim-

its Community Information Service, Inc., a nonprofit organization

devoted to disseminating information concerning neighborhood

revitalization.

Publisher: Kim Nauer nauer@citylimits.org

Associate Publisher: Susan Harris sharris@citylimits.org

Editor: Alyssa Katz alyssa@citylimits.org

Managing Editor: Tracie McMillan mcmillan@citylimits.org

Senior Editor: Annia Ciezadlo annia@citylimits.org

Senior Editor: Jill Grossman jgrossman@citylimits.org

Senior Editor: Kai Wright kai@citylimits.org

Associate Editor: Mati Pacenza matt@citylimits.org

Contributing Editors: James Bradley, Neil F. Carlson, Wendy Davis,

Michael Hirsch, Kemba Johnson, Nora

McCarthy, Robert Neuwirth, Hilary Russ

Design Direction: Hope Forstenzer

Photographers: Margaret Keady, Gregory P. Mango, John Veleas

Contributing Photo Editor: Joshua Zuckerman

Contributing Illustration Editor: Noah Scalin

Interns: Carolyn Bigda, Priya Khatkhate, William Wichert

Proofreaders: Sandy Socolar, Sandy Jimenez, Dessi Kirilova,

Mary Anne LoVerme, Roy L. Sturgeon, Hsing Wei , Richard Werber

General EMail Address: citylimits@citylimits.org

CENTER FOR AN URBAN FUTURE:

Director: Neil Kleiman neil@nycfuture.org

Research Director: Jonathan Bowles jbowles@nycfuture.org

Project Director: David J. Fischer djfischer@nycfuture.org

Deputy Director: Robin Keegan rkeegan@nycfuture.org

Editor, NYC Inc: Andrea Col ler McAuliff

Interns: Noemi Altman, Nicholas Johnson

BOARD OF DIRECTORS'

Beverly Cheuvront, Partnership for the Homeless

Ken Emerson

Mark Winston Griffith, Central Brooklyn Partnership

Celia Irvine, Legal Aid Society

Francine Justa, Neighborhood Housing Services

Andrew Reicher, UHAB

Tom Robbins, Journalist

Ira Rubenstein, Center for Economic and Environmental

Partnership, Inc.

Karen Trella, Common Ground Community

Pete Williams, Consultant

'Affiliations for identification only.

SPONSORS:

Pratllnstitute Center for Community

and Environmental Development

Urban Homesteading Assistance Board

Subscription rates are: for individuals and community groups,

$25/0ne Year, $391Two Years; for businesses, foundations,

banks, government agencies and libraries, $35/0ne Year,

$501Two Years. Low income, unemployed, $IO/One Year.

City Limits welcomes comments and article contributions. Please

include a stamped, self-addressed envelope for return manu-

scripts. Material in City Limits does not necessarily reflectthe opin-

ion of the sponsoring organizations. Send correspondence to: City

Limits, 120 Wall Street, 20th FI. , New York, NY 10005. Postmaster:

Send address changes to City Limits, 120 Wall Street, 20th FI., New

York, NY 10005.

Subscriber inquiries call : 1-800-783-4903

Periodical postage paid

New York, NY 1000 I

City Limits (lSSN 0199-0330)

PHONE (212) 479-3344/FAX (212) 344-6457

e-mai l: citylimits@citylimits.org and online: www.citylimits.org

Copyright 2003. All Rights Reserved. No portion or portions

of this journal may be reprinted without the express permission

of the publishers. City Limits is indexed in the Alternative Press

Index and the Avery Index to Architectural Periodicals and is

available on microfilm from ProQuest, Ann Arbor, MI 48106.

CITY LIMITS

FRONTLINES

Tania Savayan

Neighborhood Defense

KARIM LOPEZ SEES the Bush administration's call for war as a double

threat: An invasion ofIraq, he says, would also be an attack on his Wash-

ington Heights neighborhood.

"[Military] recruitment is aimed at poor communities of color

around the cities," he says. "It's those young people who are going to

fight and die." To drive home the point that, as Tip O' Neill once said,

"all politics is local, " the 25-year-old helped found Uptown Youth

United for Peace and Justice in the weeks after September 11. The

group, which now claims about 200 members under the age of 25, is

part of a growing uend of New Yorkers who are fighting the prospect of

war by arguing that their neighborhoods will suffer.

On February 15, members oflocal groups like Lopez's were part of the

estimated 250,000 protesters who jammed the East Side of Manhattan to

rally against the Bush administration's plans to invade Iraq.

"Money for jobs, not for war! Money for schools, not for war!" Lopez

chanted as he marched through Harlem on his way to the rally. Passing

drivers honked their horns in sympathy and passengers whooped and

whistled from open windows.

Tough economic times already threaten neighborhood resources like sen-

ior centers, literacy programs and police, not to mention broader initiatives

like college tuition assistance, community activists like Lopez argue.

If there is war, "There won't be money for schools, there won't be

APRIL 2003

money for health," predicts Frank Farkas of Bronx Action for Justice and

Peace, a group of northwest Bronx residents who carne together after the

Trade Center attacks.

These fears have inspired a proliferation of small, community-based

anti-war groups. "They want a way to connect with their own community

or others beyond their regular interest groups," says Saulo Colon of

United for Peace and Justice, which helped organize the February rally.

The group claims nearly 150 local organizations participated in the event.

Even groups that existed long before September 11 have been uans-

formed by the fast pace of the Bush administration's drive toward war.

To express his own concerns, Donald Green, 56, of the South Bronx

recently joined Mothers on the Move, a local parent advocacy group that

added anti-war efforts to its roster of activities over the last year. "They're

ralking about weapons of mass destruction," he says, but with drug deal-

ing a regular occurrence in the hallways of his apartment building, he

adds, "We've got mass desuuction right here. "

Of course, the concerns of these local groups are about more than

just war's potential effects on New York neighborhoods.

"There are going to be children who will be orphans on both sides, "

says Silkia Martinez, an organizer for Mothers on the Move. "There are

ways to negotiate without having to go to war."

-Alex Ginsberg

5

FRONTLINES

City fines

threaten to

shipwreck a new

Bronx boathouse

By Abrahm Lustgarten

LAFAYETTE AVENUE ROLLS down off of the heights

of Hunts Point, ending abruptly at the shores of

the Bronx River. On a recent morning, the

cloudy waters lapped at sunken tires and a sub-

merged radiator. Once home to a fur-dyeing fac-

tory, these shores have been contaminated for

decades. There are some signs of hope here.

Newly planted saplings grow near the old fac-

tory, and a hand-painted mural on a nearby wall

depicts how the community really sees this prop-

erty: as a launching point rather than a dead end.

Until a few months ago, local residents were

well on their way to getting what they want.

Last September, The Point, a nonprofit com-

munity development group, bought the lot

6

Brownfield Blues

from the city for $525,000, with the help of a

grant from the National Oceanic and Atmos-

pheric Association. The plan: to build a 25,000

square-foot boathouse and center where visitors

can learn about the local ecosystem, rent kayaks

and research the area's waterways.

There was one catch to the purchase, how-

ever. For the city Department of Environmental

Protection (DEP) to approve it, The Point had

to assume sole responsibility for removing the

hundreds of barrels of hazardous waste that had

accumulated over roughly 70 years of industrial

use, and to complete the cleanup within one

month of the sale. Both JE Robert, the real

estate holding firm that manages tax liens for

the city and took over the property last summer

after some mysterious fires blazed through the

factory, and the former owner, Jacob Selechnik,

were excused from any responsibility.

While The Point's executive director, Paul

Lipson, knew he was buying into a tough situa-

tion, particularly since the group had no experi-

ence with brownfield cleanup, he says the group

had no choice-it was the only spot in the

neighborhood fit for a boathouse. And he fig-

ured DEP would be helpful with the cleanup,

since it seemed in the city's interest to decon-

taminate the area.

He never expected the city's environmental

agency would bring such a straightforward

cleanup project to a halt.

The trouble started just after October 25,

the cleanup deadline. Lipson says he was cer-

tain that EcoSystems Strategies, the company

hired to clean the site, had tested and removed

all dangerous materials from the lot. The com-

pany carted away more than 260 55-gallon

drums of hazardous salt solutions, oils and

chemical powders, as well as 30 drums of non-

hazardous materials, according to correspon-

dence between The Point and DEP.

But The Point overlooked one crucial

detail-its staff failed to file all the required

paperwork with the city on time. For each of

the five days the reports were overdue, DEP

fined the group $5,000.

Their problems did not stop there. Two weeks

later, inspectors from DEP uncovered two addi-

tional barrels of hazardous waste tucked away in a

closet in the old factory. Lipson says his people

removed them right away, but still, the city added

another $50,000 in fines to The Point's tab, for a

grand total of $75,000.

While Lipson says he has no problem with

the city enforcing the law, in this case, he says,

the DEP is selectively picking on The Point

rather than helping it fix up a decades-old

blight in the South Bronx. The city has never

come down hard on any of the previous own-

ers to get the property fixed up, he adds.

"The poor schmuck nonprofit, which is us,

is lefr to foot the bill for 50 years of pollution

on that property," he says. "Seventy-five thou-

sand dollars could spell our doom as an organ-

ization, but even $30,000 would knock out our

programming for the year."

DEP spokesperson Charles Sturken says he's

sympathetic to The Point's situation, but adds

that the city is simply enforcing the rules. "We

can't bend the law for somebody just because

they are a nonprofit," he says.

Still, the process has infuriated Lipson, who at

press time was scheduled to argue against the fines

in a March 6 hearing before the DEP's control

board in Queens. Of course The Point supports

environmental regulations and their enforcement,

he says, but this particular case is an instance of

bureaucratic abuse more than purposeful enforce-

ment. The dangerous materials were removed

according to a stringent schedule, and that, says

Lipson, should have been the DEP's primary con-

cern following the June fires. In fact, he says the

CITY LIMITS

ciry should have pursued the removal before

The Point even bought the properry.

From at least one Ciry Council member's

perspective, the ciry is making a real effort to

do right by the neighborhood. "The ciry just

needs to work towards developing a more

effective brownfields policy," says Nicholas

Arture, a legislative analyst for Councilmember

Jose Serrano, who represents Hunts Point.

"There is a very steep learning curve, and some

things need to be hashed out to ensure that

things don't happen like this in the future."

That said, he adds, this is the beginning of a

new era for the DEP and the ciry's brownfield

cleanup programs. The DEP recendy assem-

bled a Brownfields Taskforce, and Mayor

Bloomberg has made brownfield cleanup a

high prioriry in his housing plan.

Still, while Ciry Hall, along with officials

from Albany, iron out a new strategy, The

Point's predicament has caught the anention of

other local nonprofit managers, who are bewil-

dered by the ciry's contradictory actions and

fear it could affect future cleanups. "They visit

you and encourage you to participate, then

they penalize you for being a participant, like

some sort of sadomasochist," says Carlos

Padilla, director of the South Bronx Clean Air

Coalition, which last year was talking with the

ciry about cleaning up another polluted prop-

erty in the South Bronx, near the TIffany Street

Pier in Hunts Point. "The DEP has sort of sep-

arated itself from the goodwill of the commu-

niry in favor of just gening their job done."

The net effect, say Lipson, Padilla, and

Omar Freilla of the group Sustainable South

Bronx, is that communiry development

organizations are ultimately dissuaded from

investing in environmental cleanup. "There

is no current policy that enables that land to

be cleaned up in any kind of effective man-

ner," says Freilla, whose organization is plan-

ning to develop a greenway public access

strip along the Hunts Point waterfront.

As for The Point, if it is able to get the fines

dismissed, it will continue with the cleanup,

which Lipson estimates will cost more than

$300,000. The group has to replace the con-

taminated topsoil , dispose of asbestos roofing

and raze the shell of the remaining building.

"We don't have a reserve fund. That's the

downside of nonprofits taking on projects

like this," Lipson says. "Maybe we shouldn't

be doing this in the first place. But who

knew, that, God, the DEP might not be a

partner on this?"

Abrahm Lustgarten is a Manhattan-based free-

lance writer.

APRIL 2003

FRONT llNES

URBAN lEGEND

Home

Base

SEVEN YEARS AGO, Damaris Reyes

thought of nothing but making

enough money at her cory telecom m u-

nications job to get out of the public

housing project she'd lived in her

whole life.

She wanted to achieve the

American dream of "striking it

rich," she says.

But in 1996, when she heard that

members of Congress were drafting a

law to eliminate the cap on rents in

public housing, she dropped her plan,

dug in her roots at the Baruch Houses

and began speaking up for tenants'

rights.

"It's one thing if you wanna go,"

~ Reyes says. "But to know that some-

;jl

~ one could come and pull the rug

from underneath you .. . "

She volunteered with a coalition of tenants to battle the bill-and they won.

Now, as a coordinator at Public Housing Residents of the Lower East Side (PHROLES), a grassroots tenant

advocacy group, she is taking on the debate over how to redevelop lower Manhattan.

To figure out how she and her neighbors can playa significant part in the planning process, Reyes trav-

eled to Europe in November as part of a New York to Europe Study Tour organized by the Pratt Institute Cen-

ter for Community and Environmental Development. The excursion took 50 New Yorkers-from labor leaders

and manufacturers to small business owners and Trade Center family members-to Berlin, Munich, Bologna

and Morena to learn how low-income people engage in development projects in western Europe.

More typically, this third generation public housing resident spends most of her days focusing on the

tenants of the Lower East Side, and how they can land construction jobs in their housing projects or nav-

igate their way through housing court.

Organizing tenants, or as Reyes, 31, puts it, "giving them the tools to fix their own problems," became

her full-time job in 1998 when she got a job with City Councilmember Margarita Lopez. Reyes worked to

get tenants to learn about and testify on the New York City Housing Authority's annual plan, which she

says is "the one chance a year to have your voice heard and participate. "

Three years ago, she joined PHROLES. "She's so good at relating to people," says Legal Aid attorney

Adriene Holder, who, with Reyes' help, is offering workshops at PHROLES to teach hundreds of local public

housing residents how to negotiate Housing Court and to understand their disaster relief benefits.

At a workshop at Lillian Wald Houses, in a stuffy, cement-blocked room, Reyes teaches about 50 ten-

ants how to file a complaint against the city Housing Authority. "Listen," Reyes reasons, without mother-

ing, "we are in a serious housing shortage and we can't afford for one person to not know your rights."

Every day, Reyes sees residents who lose their homes, she says. Those evictions, she adds, are a loss that

"we absolutely cannot afford. " - Elizabeth Cline

7

FRONT LINES

Local groups

have a year to

prove reducing

garbage pays.

By Tess Taylor

JUST OFF OF HUNTS POINT Avenue in the Bronx,

in a warehouse the size of a football field, Mor-

gan Powell and Tom Morgan pore over bins

full of old motherboards, cracked monitors

and defunct graphic scanners. "That's sure an

antique," Morgan says, gently kicking one

gape-faced TV

Despite its appearance, this isn't a dump,

but a recycling center where Morgan and Pow-

ell are working on innovative programming

designed to reduce the amount of toxic elec-

tronic waste that passes out of the city each

year. Per Scholas, a nonprofit that has been

8

Fast Trash

collecting e-waste from businesses since 1999,

refurbishes salvageable computers and then

sells them for less than $300 to low-income

families in the tri-state area.

Electronic appliances that cannot be saved

are sent up a 50-foot-Iong conveyor belt, where

they are crushed and shredded for safe recy-

cling. ''This way, we keep some of the toxies,

like lead, from ending up in the ground some-

where, " says Powell, who works as a waste pre-

vention community coordinator with Sustain-

able South Bronx, an environmental group in

Hunts Point that is partnering with Per Scholas

on this project.

Morgan and Powell's project is part of a new

$1 million trash reduction program that the

City Council is funding over the next year.

The program had its genesis in 2000, when

Mayor Rudy Giuliani closed the Fresh Kills

landfill. While the move won the mayor big

applause from the residents of Staten Island,

home to one of the nation's largest dumps, it

created stinky polities for many other city

neighborhoods-the plan redirected city waste,

by truck, to waste transfer stations in Red

Hook, Williamsburg and the South Bronx.

"A lot of community groups got together

and said that simply moving the garbage prob-

lem to our back yards was unacceptable, and

that the city must make a concerted effort to

reduce waste," says Eve Martinez ofINFORM,

Inc., an environmental research group that is

helping administer this year's funding.

Members of the City Council agreed

and called for the city to invest about $6.5

million over [wo years in community trash

reduction. "We knew we needed to lessen the

impact on communities where there are trash

transfer stations," remembers Carmen

Cognetta, a lead staffer on the Council's sani-

. .

tanon comml[tee.

But the Department of Sanitation was slow

in awarding the contracts for the waste reduc-

tion program, and after September 11, New

York's downward economy pushed it even fur-

ther aside. By the time the program launched

this year, funding had shrunk to $1

million-$285,000 for the Council on the

Environment, which will focus on waste

reduction in the public schools, and $715,000

for INFORM.

To make their funding go as far as possible,

INFORM chose seven community groups like

Per Scholas that already run trash reduction

programs. Now, these groups only have until

the end of the year to show that their innova-

tive recycling efforts could save the city money

while helping the environment. Breaking even

alone would be no small feat: To recoup the

$715,000 City Council grant, INFORM's

programs will have to divert a total of 11 ,171

rons of waste this year. (The city currently

pays its garbage haulers $65 a ton.)

Martinez, for one, is skeptical that one year

is enough time to do that. "It takes people time

to change their habits, and it takes time for the

effects of any outreach to show, " she says. That

said, she hopes this grant from the city can

serve as a catalyst for future support.

For now, in Manhattan, the Lower East

Side Ecology Center is zeroing in on food

scraps with a $90,000 grant from INFORM.

The group plans to expand its 15-year-old pro-

gram of collecting vegetable waste from neigh-

borhood residents, and transforming it to rich

potting soil and garden compost, which the

organization then resells at farmers' markets.

"We call it pay dirt," quips Christina Datz-

Romero, who leads the effort.

Compost education programs at the

CITY LIMITS

botanic gardens in Brooklyn and Staten

Island-slashed in the latest city budget

cuts-will get a revival and new direction

from the INFORM funding. Their focus:

grass clippings. "Since lawn clippings are

mostly water, they are heavy and very expen-

sive for the Department of Sanitation to haul

away, " says Mark Vacarro of Staten Island.

"But if you just leave them be, they make great

lawn mulch. "

And in Queens, the community group

Astoria Residents Reclaiming Our World has

teamed up with entrepreneur Nicole Tai to

create a drop-off center and pick-up schedule

for the city's myriad construction and demoli-

tion wastes-everything from doors to door-

knobs to bricks. [See "Material World, "

page 22.]

Whatever happens with next year's budget,

leaders of the sponsored groups are deter-

mined to keep their operations going. "We see

it as crucial to begin modeling other ways that

the city might dispose of its goods, " says

Omar Freilla of Sustainable South Bronx.

Especially, he says, since a recent transporta-

tion study of the area found that his neighbor-

hood of 10,000 residents is visited by 11,000

diesel (rucks a day.

Tess Taylor is a Brooklyn-based freelance writer.

APRIL 2003

Off the Map

RESIDENTS OF WASHINGTON HEIGHTS and

Inwood are accustomed to tourists and other

fellow New Yorkers thinking that "uptown"

means the stretch between 96th and 125th

streets, as if anything further north is part of

upstate New York.

After years of watching their neighborhoods

get cut out of tourist maps of Manhattan, how-

ever, some local residents of what they call the

"real" uptown are taking city agencies to task.

In mid-January, members of Community

Board 12, which covers Manhattan above

155th Street, unanimously passed a resolution

calling on the Meuopolitan Transit Authority,

the Department of Cultural Affairs and New

York City & Co., the city's tourism agency, to

withhold pubLic funds from any company that

excludes Washington Heights and Inwood

from its maps of Manhattan.

These maps "undermine tourism in the neigh-

borhood," says Zead Ramadan, the community

board chair. "They undermine great institutions

such as the Cloisters, Fort Tryon Park and sites of

significant Revolutionary War battles."

On top of all that, he adds, "They send the

FRONT LINES

message that people don't want to go uptown. "

The problem is certainly real. An informal

survey of 10 New York City travel guides showed

that none include maps that extend above 145m

Street, and almost all are limited to attractions

south of 11 Oth. One online map, Citymaps.com,

claims to show "a full view of the island of Man-

hattan," but the map ends at 113th Street.

The private firms say they will include

northern Manhattan when they see some

money from uptown venues. "No attractions

from up there advertise with us," explains The

New York City Travelguide's publisher Peter

Flower. "If they gave us money, I would put

them on the map."

City and state agencies say they would Like

to be as inclusive as possible, but, says Henry

Rissmeyer of the MTA, which sells maps to

travel guides that cut off at 150th Street, a map

of the whole city would be unreadable. "It

would be possible to produce a map of the

whole island, but the question is whether it

would be functional ," he adds.

Still, Ramadan is determined to send a mes-

sage. "These private companies are missing out

on some of the most important attractions in the

city," he says. By excluding northern Manhattan,

"they are undermining the tourism initiatives

and keeping vital information from people. "

-Penelope Ouda

9

FRONTllNES

Bush's Taxing Idea

"I ASK YOU TO END the unfair double taxation

of dividends," President Bush said to congres-

sional applause during his State of the Union

address in January. Under the president's pro-

posal, the Internal Revenue Service would

allow corporations to pay tax-free dividends to

their shareholders.

That might have sounded good to some at

the time. But if put into effect, the Bush plan

could end up gravely wounding the decades-

old federal program that generates corporate

investment in affordable housing.

Congress and President Reagan created the

Low Income Housing Tax Credit program in

1986. Under this law, the feds award each state

$1.75 in tax credits per capita annually-

$33.2 million for New York in 2001. Local

housing agencies, the state Division of Hous-

ing and Community Renewal and the city

department of Housing Preservation and

Development then award those credits to

nonprofit housing developers building new

affordable apartments. Those developers, in

10

turn, raise money by selling those credits, typ-

ically through an intermediary, to corpora-

tions, which then cash in those tax credits

with the IRS to lower their tax bills.

These tax credits help support the consuuc-

tion of roughly 3,000 housing units per year in

New York City and about 115,000 nationally.

But if this new incentive is offered, afford-

able housing developers and advocates fear,

corporations' interest in buying tax credits

will diminish as well. "The low income hous-

ing credit would be virtually worthless, "

Harlem Congressman Charles Rangel recently

wrote in a letter to federal housing secretary

Mel Martinez.

Housing is not the only industry that could

be hurt by Bush's proposal. There are similar

tax credit programs for investments in inner

city retail development, renewable energy, and

even in oil and gas exploration. Some invest-

ment professionals speculate that the proposal

could also hurt corporate charitable giving,

which reduces tax burdens, as well as the mar-

ket in tax-free municipal bonds.

Congress is expected to consider Bush's full

tax plan within the next few months. In the

meantime, to determine if their fears are war-

ranted, some national housing groups have

hired the accounting firm Ernst & Young to

analyze the situation.

Housing professionals are hopefUl that the

Bush administration will reconsider the dividend

tax cut---or that Congress will modifY the pro-

posal to allow corporations to count money spent

on the housing tax credit as taxable income. They

are somewhat optimistic, not least because the

Bush administration lobbied Congress last year

to create a new housing tax credit that would

support single-family homeownership.

"I find it hard to believe that the policy peo-

ple in the White House are aware that [the div-

idend tax cutl undercuts their own policies and

proposals, " says David Casson, a vice-president

at Boston Capital, a tax credit syndicator. "It

just doesn't make sense. "

- Matt Pacenza

CITY UMITS on the web!

www.

c itylimits-.

org

Become A Partner Organization

Public Allies is a leadership development organization. To achieve our

mission, we partner with non-profit organizations and provide 10-month

paid apprenticeships for young adults committed to social change.

To host a Public Ally full-time from September-June 2004, costs $12,400.

Applications are due May 2, 2003.

For more information,

contact us at

212-244-5335 or

newyork@publicallies.org.

II

PUBLIC ALLIES

NEW YORK

www.publicallies.org

CITY LIMITS

INSIDE TRACK-

Off the Waterfront

A thriving seaport may get downsized-and take New York's

shipping industry with it. By Alyssa Katz

Kevin Catucci's American Stevedoring has transformed the Red Hook Marine Terminal into a bustling port-

which may not be what the city wants.

"THIS IS MY WATERFRONT! You mess with it, I

break your legs!" This is the public statement of

a cheerful black-and-white dog, wearing sun-

glasses and clamping an unlit cigarette in his

mouth. The man moving the dog's jaw and

speaking on his behalf is Kevin Catucci, Exec-

utive Vice President of American Stevedoring.

Since the family-run shipping company took

over a lease from the Port Authoricy of New

York and New Jersey in 1994, the marine ter-

minal in Red Hook, Brooklyn, has been trans-

formed from a moribund outpost to a thriving

port, right near the belly of lower Manhattan.

On any given day, it employs upwards of 200

APRIL 2003

people, depending on the volume of boat traf-

fic, and Catucci claims an annual payroll of$37

million. Piles of lumber bound for Home

Depot, sacks of cocoa from Indonesia heading

to Nestle, truck-size containers of the power

beverage Red Bull-this is how they all come

into New York. "We've made a success out of

Red Hook," boasts Sal Carucci, Kevin's father

and CEO of the company.

But the Catuccis and their business may not

be in Red Hook for much longer. Their lease

expires a year from now, and the Port Authoricy,

which leases the site from the cicy's Economic

Development Corporation (EDC) and spends

several million dollars a year to keep it going,

has sent strong signals that it does not intend to

renew it.

This winter,. the Port Authoricy and EDC

hired the consulting firm Hamilton, Rabi-

novitz & Alschuler (HR&A) to study the eco-

nomic viabilicy of other possible uses for the

80-acre Red Hook Marine Terrrlinal site, which

encompasses Brooklyn piers 6 through 12-

including housing, retail and recreation. The

two agencies' request for proposals (or a "Pre-

ferred Alternatives Development Plan" stresses

"strategic advantages" that could attract devel-

opers, including "idyllic vistas of the Manhat-

11

Your Neighborhood Housing

Insurance Specialist for over 25 Years

INSURING Low-INCOME CO-OPS,

NOT-FOR-PROFIT COMMUNITY GROUPS

AND TENANTS

Contact:

Ingrid Kaminski , Senior Vice President

212-269-8080, ext. 213

Fax: 212-269-8112

Ingrid@8ollingerlnsurance.com

Bollinger, Inc.

One Wall Street Court, New York, NY 10268-0982

www.Bollingerlnsurance.com/ny

Need a Lawyer Who Understands

Housing and Homeless Services?

As nonprofits respond to the City's affordable housing

crisis and the growing number of homeless New Yorkers,

Lawyers Alliance for New York is expanding its work to

target more groups that assist the homeless. Whether your

nonprofit provides food, shelter or permanent housing, job

training or other social services to the homeless, Lawyers

Alliance can assist with your organization's business law

needs. Our staff and volunteer attorneys have experience

with nonprofit, corporate, real estate, low-income tax credit

and other legal issues that can affect nonprofits that are

creating affordable housing and serving the homeless.

For more information, call us at 212-219-1800 ext. 223.

330 Seventh Avenue

New York, NY 10001

212 219-1800

www.lany.org

Lawyers Alliance

for New York

Building a Better New York

Lawyers Alliance congratulates City Limits and the Center

for an Urban Future on 26 years of making a difference!

12

tan skyline ... proximity to major business dis-

tricts .. . and a number of economically and cul-

turally vibrant neighborhoods, such as Carroll

Gardens, Cobble Hill and Park Slope."

Even in the current weak economy, the Red

Hook waterfront could attract big private devel-

opment dollars. At the eastern border of the

marine terminal, a Boston developer is looking to

turn a former dock warehouse into lofts. Directly

ro the north is the site of the soon-to-be Brook-

lyn Bridge Park, which the Port Authority has

committed $85 million to help build on its old

piers 1 through 5. And just to the west is the hot

property of Governor's Island.

One of HR&A's tasks will be to identify

developers and commercial tenants who are

interested in the Marine Terminal site; another is

to assess the real estate market and land use

trends just inland from the waterfront. The con-

sultant will ultimately come up with three or

more development schemes that maximize eco-

nomic benefits for the neighborhood, city, state

and Port Authority.

But even if HR&A discovers that new com-

mercial development could bring in more public

revenue than a port, some urban planners argue

that shutting down shipping would be disastrously

shortsighted. "A diverse economy that includes a

balance of industry and commerce and services is

a key to urban stability," points out Laura Wolf-

Powers, a planner with the Pratt Institute Center

for Communiry and Environmental Develop-

ment. "The Port Authority is driving this, and

EDC is going along. Someone should hit them

upside the head and say, 'What are you doing?'"

Wolf-Powers is talking with the Municipal Art

Society and the South Brooklyn Local Develop-

ment Corporation about putting together an alter-

native plan for the site that would focus on retain-

ing industrial and maritime operations.

Congressman Jerrold Nadler, who has been

on a decades-long crusade to unclog freight com-

merce in the New York region, is outraged that

the Port Authority may effectively end all ship-

ping in New York outside of Staten Island. "They

have managed to concentrate everything in

Newark Bay instead of New York Harbor," says

Nadler. As the congressman asks his colleagues

on the House Transportation Committee to pro-

vide billions of dollars to help move freight in

New York, he believes shutting down Red Hook

would send the message that New York City isn't

even interested in maintaining its existing ship-

ping operations. "When has the Port Authority

ever closed an existing port?" demands Nadler.

JUST A COUPLE OF YEARS AGO, it would have been

hard to imagine City Hall letting the Port

Authority back out of Red Hook. In 2000, EDC

spent $12 million to add two new cranes to Red

Hook's waterfront, helping bring the marine ter-

CITY LIMITS

minal.s shipping volume to an all-time high of

about 80,000 containers a year. It was part of an

ambitious plan from EDC to expand the city's

ports, including building an entirely new opera-

tion in Sunset Park, Brooklyn.

This was the rare Giuliani economic devel-

opment scheme that promised to payoff for

New Yorkers. In 1999, Giuliani's EDC pre-

dicted that cargo demand in the New York area

was going to triple by 2020, and that every inch

of port space in the region needed to be used

both to keep port jobs from fleeing elsewhere on

the east coast and to keep local roads and air

from strangling on truck traffic.

All in all, the port plan called for an invest-

ment of $1.5 billion over 20 years to develop

1,200 new acres of port space in the city, bring-

ing 30,000 jobs and $300 million in annual tax

revenue. Red Hook would triple its container

volume by 2010, at which point the entire oper-

ation would move further down the Brooklyn

waterfront to the new and bigger port in Sunset

Park, which would have access to rail lines. From

then on, Red Hook would specialize in "break

bulk" cargo like cocoa and bananas, shipped in

piles and sacks instead of containers, hundreds of

thousands of tons of it a year. The city's plans also

called for doubling the size of Howland Hook, in

Staten Island, which the Giuliani administration

reopened as a container port in 1996.

But a full-fledged port running the length of

Sunset Park will cost hundreds of millions of dol-

lars. Building out Howland Hook to its full

capacity will cost the city another half-billion.

Facing record budget deficits, the city is now

assessing whether it will move forward with port

development. The Bloomberg administration

will not comment on the status of the previous

administration's port plans. "It's premature to dis-

cuss," says EDC spokesperson Janel Patterson.

"That's the purpose of the study, to give us an

idea of the best use of the [Red Hook] site."

The future of a Sunset Park port also depends

on dollars and decisions from Washington. This

September, Congress is set to reauthorize major

transit legislation known as TEA-21, and Rep.

Nadler is determined to use the new appropria-

tion ("TEA-3") to fund a cross-harbor freight

tunnel. This is the very project, as Nadler relishes

pointing out, that the Port Authority was created

to build in the first place. The tunnel would per-

mit freight trains to cross the harbor from Bay-

onne to Bay Ridge, just south of Sunset Park,

then roll onto currently unused train tracks

crossing Brooklyn and Queens.

The immediate effect would be to take mil-

lions of truck-miles off the roads. But a tunnel

would also make Brooklyn ports viable: Sunset

Park, with wide-open ocean access, naturally

deep waterways, unused rail lines and now a

way to get freight across the harbor to the

APRIL 2003

LEGAL ASSISTANCE

FOR NON PROFITS & COMMUNITY GROUPS

N Y L P I

New York Lawyers For The Public Interest 15 1 W 30 St, New York, NY 10001 2122444664

Community Planning and Development Mini-Courses

Following up on the Planning into Practice conference, Hunter College Department of Urban

Affairs and Planning and the Municipal Art Society Planning Center invite members of

community based organizations, Community boards, citizen and advocacy groups, graduate

students, city agency managers, professionals and employees to continue the dialogue.

HUNTER COLLEGE

(6t

h

Street and Lexington A venue)

Registration and Information:

Call William Beaufort 212-772-5517

Email : wbeaufor@hunter.cuny.edu

Fees: $25 for each session

For CUNY Credit (entire series)

Graduate $562.85 Undergraduate $526.95

HOW TO

~ T ~ ---------------------------------------------------

Feb. 6 Opening session: Eddie Bautista, NY Lawyers for the Public Interest; Tony Avella,

NYC Council member, Christopher Kui, Executive Director, Asian Americans for Equality

Feb. 13 Engaging the budget process: TBA

Feb. 20 Developing and Implementing 197-a plans: Jocelyn Chait, Planning Consultant

Feb. 27 Developing affordable housing in changing neighborhoods: Brad Lander, Fifth

Avenue Committee

Mar. 13 Safe streets and traffic calming: Lisa Schreibman. Hunter College

Mar. 20 Historic districts as community preservation: Vicki Weiner, Municipal Arts Society

Mar. 27 Planning and zoning for mixed use: Eva Hanhardt, Municipal Art Society Planning

Center

Apr. 3 Green buildings and sustainable communities: TBA

Apr. 10 From waste transfer stations to comprehensive waste management: Timothy Logan,

NYC Environmental Justice Alliance

Apr. 24 Brownfields development: Mathy Stanislaus, Environmental Consultant

May 1 Inclusionary Zoning Laura Wolf-Powers. Pratt Institute

13

14

NANCY

HARDY

Insurance

Broker

Specializing in

Community

Development

Groups,

HDFCs and

Non-Profits.

Low-Cost Insurance

and Quality Service.

Over 20 Years

of Experience.

270 North Avenue,

New Rochelle, NY

10801

914-636-8455

INSIDETRACK

mainland, has the potential to be a valuable

star in the harbor's constellation of ports.

At Nadler's prodding, the Bloomberg

administration made one small step in Febru-

ary, when it agreed to put a freight tunnel on

its list of priority TEA-3 funding requests to

Congress. And EDC is currently in negotia-

tions with a Georgia company to run a new

auto terminal at 29th Street in Sunset Park, the

first phase of the full port plan.

But without firm commitments from EDC

on the future of the Sunset Park port, even

would-be supporters of new housing develop-

ment in Red Hook say the city can't afford to

lose the Marine Terminal and its high-paying

jobs. "If they have a port at Sunset Park, I have

less trepidation about losing the Red Hook

container port," says City Councilmember

David Yassky, who

lease"-until April 2004.

"We're looking to find out if there is a bet-

ter use for that property," says Port Authority

spokesperson Steve Coleman. "We're really

concerned about the subsidy the POrt Author-

ity has to continue to pay for Red Hook."

Larabee also alluded to "a variety of new eco-

nomic realities confronting New York City and

the region." Though he didn't identifY it, one

reality is the vow of the Danish shipping giant

Maersk Sealand to abandon its operations in

New York Harbor if the Port Authority fails to

dredge its New Jersey shipping terminals and

waterways to a depth of 50 feet by 2009. The

agency has committed to spend billions of dol-

lars to bore its way through toxic sludge and

rock in Newark Bay. The Red Hook port,

which accounts for just 2.4 percent of all the

goods shipped into

chairs the Select

Committee on

Waterfronts. "With-

out knowing more

clearly what's hap-

pening in Sunset

Park, I'm very leery

about losing the last

container port in

Brooklyn, Queens

and Manhattan."

NO MATTER HOW the

city proceeds, the

future looks bleak for

American Stevedor-

ing. The Catuccis

"I'm very leery

about losing the

last container port

in Brooklyn," says

Council member

David Yassky.

New York Harbor,

costs the Port Author-

ity money but does

nothing to help retain

Maersk.

Phoenix, however,

wouldn't need a costly

cross-harbor barge,

and neither do other

operations like it-

companies that are

simply trying to get

bulk goods from the

mainland into Brook-

lyn, Queens and

Long Island via water

have been talking to Phoenix Beverage, a New

Jersey company that distributes Heineken and

other beers, and currently delivers the goods

from Elizabeth to New York City via truck.

Phoenix has expressed a willingness to move its

east-of-the-Hudson operations from Long Island

City to Pier 12, bringing perhaps 650 more

jobs-but only if the move comes with a long:-

term lease commitment from the Port Authority.

Under the current terms, a new lease is the

last thing the Port Authority wants. The agency

spends $267,000 a month for a barge to shut-

tle containers back and forth berween Red

Hook and transportation connections on the

mainland in New Jersey, so that goods coming

through Red Hook can travel west of the Hud-

son River. (The Catuccis say they pay another

$76,000 to keep it going.) Last October, Port

Commerce Director Richard Larabee told the

City Council Select Committee on Water-

fronts that "the Port Authority will continue to

fund this service through the end of the new

instead of truck. In

an effort to convince the Port Authority to

keep the Red Hook Marine Terminal going,

some local officials are now floating the idea of

an alternative to the international container

port American Stevedoring wants to keep run-

ning: a local niche operation that doesn't cost

the Port Authority anything to keep afloat.

Tenants like Phoenix could be rounded out by

Carnival Cruise Lines, which has expressed

interest in building a berth at Piers 6 and 7.

Supporters of the alternative say that turn-

ing the Marine Terminal into a local delivery

depot would be the best of all worlds: a way to

keep port jobs in New York and Red Hook,

and to keep trucks off the roads. At that site,

"a container port probably isn't going to be a

profit-making industry," says one government

aide. Rethinking the Red Hook port is fine,

says the aide, as long as the neighborhood

retains a working waterfront: "That's not a bad

thing--especially from the point of view of

the Port Authority."

CITY LIMITS'

4th Annual

READY. WORK. GROW.

National Workforce Conference:

Helping People Overcome Barriers and Build Careers

March 19-21, 2003

Baltimore Marriott Waterfront I Baltimore, Maryland

" THE ENTERPRISE FOUNDATION

APRIL 2003

JOIN OVER 750 WORKFORCE

PROFESSIONALS from across

the nation as we work to help

people overcome barriers and

build careers!

WORKSHOP TOPICS

One-day pre-conference allowing

attendees to focus in-depth on

six key workforce topics:

Working with ex-offenders

Workforce public policy

Building business customers

Boosting job retention

Revolutionizing how you train

your participants

Managing for outcomes

Two-day main conference featuring

30 workshops spread across the

following five tracks:

Workforce Keys

Housing and Employment

Innovative Workforce Models

Serving Special Populations

Working with the System

KEYNOTE SPEAKERS

Hear keynote speakers Mark Greenberg

from the Center for Law and Social

Policy and nationally acclaimed author,

trainer and speaker Jim Smith, Jr.

J.P. MORGAN CHASE AWARDS

The winners of the J.P. Morgan Chase

Awards for Excellence in Workforce

Development will be announced during a

special plenary session. Each of the three

winners will receive an unrestricted

grant of $15,000. Find out what made

them winners!

REGISTER BY FEBRUARY 7

AND SAVE $100!

REGISTER ON-LINE

www.enterprisefoundation.org

QUESTIONS?

Call 410.772.2760 or email us at

workforceconf@enterprisefoundation. 0 rg

15

16

They take millions in

government housing dollars.

Transfer loads to their

private ventures.

BY GEOFFREY GRAY

They were down in Texas on business, walking

through historic San Antonio, when the call about King Tone came on

the priest's cellular phone. Tone, born to the world Antonio Fernandez,

was then leader--or "Supreme Inca"--of the Almighty Latin King and

Queen Nation street gang, and he'd been busted, again. He'd punched

his old girlfriend in the face, giving her a black eye in front of her 11-

year-old daughter, and violated his parole, according to the 1997 charge.

He was locked up and needed $5,000 bail.

The priest, Reverend Gordon H. Duggins, had come to know Tone and

many other Latin Kings gang members. He'd hired them too--some off the

books, some on- to work security and operations for the homeless shelters

and single-room occupancy (SRO) hotels that he and G. Sterling Zinsmeyer

run through Praxis Housing Initiatives, one of the city's largest nonprofit

providers of housing and social services for homeless people with AIDS.

Tone was never on the Praxis payroll, though occasionally he'd sign

petty cash slips at Praxis for $150, or Duggins would borrow money from

employees ro buy him suits for his court dates. At the time, Tone had pub-

licly promised to transform the Kings from a band of drug dealers, with a

reputation for violence, into a respected and charitable organization. Dug-

gins believed that promise, and was willing to foster the gang's altruistic

transition- at any price, it would seem.

Rather than reach into their own pockets to spring the gang leader,

Duggins and Zinsmeyer-who each made $120,000 in salary that

year--dipped into the coffers of their nonprofit, at the expense of their

clients and the public.

To help Tone out of his latest legal jam, Duggins, Zinsmeyer and

Praxis' then-comptroller, Hugo Puya, ducked into the historic Merger

Hotel, only yards away from the old Alamo battlegrounds, and penned a

fax. "Funds need to be transferred directly out of Praxis Chase bank

account and directly transferred into Mr. Ronald L. Kuby Chase

account," read the note, signed by both directors. A letter dated that same

CITY LIMITS

House the homeless?

For the executives at Praxis,

that's the mission-

not the bottom line.

day from Kuby, Tone's pro bono attorney, confirmed receipt of the trans-

fer and money used for Tone's bail.

As documents obtained by City Limits reveal, Tone's bail is just one

item in a lengthy list of questionable expenditures the Praxis executives

have made since they founded the group eight years ago. In mid-Febru-

ary, following a report in City Limits Weekly, these spending practices

caught the attention of the city Department of Investigation, the state

Attorney General and the Inspector General at the federal Department

of Housing and Urban Development, all of whom are now examining

the organization's financial records. Nearly all of Praxis' $7.4 million

budget comes from city, state and federal funding streams, and investi-

gators are trying to figure out where taxpayer dollars are going.

"We're looking at how the money was spent, and we're taking this

very seriously," says HUD spokesperson Adam Glantz.

Among the more curious enterprises is a string of stealthy for-profit

homeless hotels that Duggins and Zinsmeyer have set up under the Praxis

umbrella. Tax returns and internal company memos show that the directors

arranged for hundreds of thousands of dollars to be siphoned from the

nonprofit to start up and support their private housing enterprises-unbe-

knownst to the Praxis board of directors, or to the Internal Revenue Service.

"It's a huge scandal," says founding Praxis board chair Cyril Brosnan,

who resigned last summer after years of "disgust" and "frustration" with

the executives' financial decisions and their failure to disclose informa-

tion. "We were never told about a for-profit. We were never really told

about anything," says Brosnan, who has sat on the boards of a number

of nonprofit health service groups. "They should be hung by their toes."

In an interview, Zinsmeyer, 55, admitted that blowing nonprofit

dough on the bail, for one thing, was a mistake. "It should have never

happened," he says. He claims that all money borrowed from Praxis for

both the bail and the for-profit shelters has been paid back. (He offered

to provide documentation, but failed to return repeated phone calls to

APRIL 2003

17

follow up.) "By now I think we've made all the mistakes you can make

in this business. But that's how you learn. "

Duggins declined to comment for this story. But his patronage of Tone

didn't end that day at the Alamo. Five months after Tone's assault charge,

which was later dismissed, police and FBI agents arrested Tone in a citywide

drug raid and charged him with conspiring to deal heroin and cocaine. Dug-

gins came to his rescue again, dropping another $5,000 in bail-this time

in cash. It's unclear where that money came from. Caught selling drugs on

videotape, Tone was forced to plead guilty. He's now serving a 12-year sen-

tence in a maximum-security federal prison in Terre Haute, Indiana.

"I made a fool of myself," Duggins said in a New York Times profile

in 2001 , about putting his faith in Tone. "But I would rather have stood

for him as a fool than failed him as a friend."

As a nonprofit organization with tax-exempt privi-

leges, Praxis is bound by fiduciary duty to pursue reasonable and fair-mar-

ket spending practices that support the group's mission. However, since their

first year in operation, both Zinsmeyer and Duggins have broken the Praxis

The nonprofit's spending power has also gone to support family

members. The health and worker's compensation insurance Praxis offers

its employees are both purchased through AMCORP, a San

Antonio-based fmancial services company owned by Zinsmeyer's

brother William, and his nephews, Vincent and Craig. The Internal

Revenue Service requires nonprofits to disclose any business with family

members on their tax rerurns, which Praxis has neglected to do.

"It was hardly a fair-market deal," says former Praxis comprroller

Hugo Puya. "It would have been at least 25 percent cheaper to go

straight through the insurance providers. But when it comes to family,

'cost-benefit' becomes a different type of analysis."

There's also Duggins' own personal business interests. Some of the

furniture in Praxis' shelter rooms was purchased from Woods Edge

Resources, a consulting company that he owns and runs out of his home

in Bethlehem, Connecticut. To make the dressers and bureaus, he set up

a wood shop in his garage and hired a carpenter.

"That was just an experiment," says Zinsmeyer, adding that it was

quickly aborted.

Since their first year in operation,

both Zinsmeyer and Duggins have broken

the Praxis piggy bank for other causes,

including personal items and gifts,

for-profit housing ventures,

and the businesses of

family members.

piggy bank for other causes, including personal items and gifrs, their for-

profit housing ventures, and the businesses offamily members, records show.

Before the Christmas of 1997, for instance, Duggins took the Praxis

credit card on a shopping spree, dropping $968.85 at Toys"R"Us, the major-

ity going toward PlayStation video games. That same day at Macy's, he also

charged nearly $1,000 on men's designer clothes-Nautica, Tommy Hil-

figer, Polo-including jeans and slacks ($500), and more than $175 in men's

underwear. Receipts also show he bought $625 worth of home heating fuel

and spent $347 at a Gulf gas station near his home in Connecticut.

"Gordon couldn't stop spending on the Latin Kings," says former

Praxis bookkeeper George Serrano. While it's unclear where the toys

went, Serrano claims that Duggins and some of the Kings rerurned to the

office that day carrying Macy's shopping bags and sporting new clothes

with the Macy's tags still on. "He'd take all the petty cash he could, ask if

he could borrow money personally, anything we had in our wallets. He

promised to pay us back and he never did. It wasn't like we weren't pay-

ing him-we gave him $120,000 in salary. " Last year, in addition to their

for-profit ventures, the execs also took a salary raise, Duggins pulling

down $135,231, and Zinsmeyer making $149,539.

18

Other businesses continue today, though, including

their most lucrative: a cluster of for-profit homeless shelters and single-

room occupancy hotels that the execs have set up through separate hold-

ing companies.

For $90 or more a night, the city Department of Homeless Services

(DHS) sends single adults and families to the Dawn Hotel and Heights

Residence in Harlem, the Bronx's Park Overlook, and Pacific Place and

Pacific Dean Residences in Brooklyn.

While Praxis manages these facilities-and some have been mislead-

ingly advertised on Praxis newsletters as part of the organization-they

are actually controlled by Duggins and Zinsmeyer, who split the com-

pany shares evenly, according to state and tax records.

It's by no means unusual or illegal for nonprofit groups to set up for-

profit subsidiaries. It gets dangerous, however, when their funding

streams mingle to benefit company executives and those executives do

not disclose that information, say lawyers and accountants.

That's what's happened at the Dawn Hotel. According to an internal

audit of the Dawn from 1997, at least $173,000 was drained directly

from Praxis-in the form of "non-interest-bearing" funds- to get the

CITY LIMITS

for-profit hotel renovated and running.

"That's a pretty risky venture," says Marc Owens, former head of the

IRS's tax-exempt organization division. He says that type of loan might

violate certain fair-market laws. "Who borrows money with no interest?

That's a diversion of assets, an excess benefit transaction."

Accounting records from the Dawn also show that at least some of

the money being diverted to the for-profit hotel came from federal

funding intended for renovations and social services at nonprofit Praxis

shelters. Between 1996 and 2002, HUD awarded Praxis $4.7 million to

run Riverside Place, a single-room occupancy residence on the Upper

West Side. According to the Dawn's 1997 general ledger, the execs

transferred $137,000 from the bank account of the Riverside to the

Dawn in just 48 days.

That same year, at least another $300,000 of Praxis' money was put

into the for-profit Latham Hotel, according to confidential letters writ-

ten by Zinsmeyer to Praxis' primary counsel, Dwight Kinsey (who also

serves as counsel to the Dawn, and last year was named chair of Praxis'

board). The Latham eventually tanked.

"It's like a shell game in the park," says Puya, who as comptroller had

regular access to the organization's books and records. "The money went

from the pockets of taxpayers, through the nonprofit, and finally into

the pockets of for-profit bank accounts controlled by both directors. "

Apparently, the directors never told the IRS that these side businesses

even existed. According to Praxis tax returns filed from 1996 through

2002, when asked if the nonprofit "ever engaged in the lending or leas-

ing or transfer of assets with for-profit companies that may have the

same directors, key officers or officials as the non-profit," accountants

routinely checked "No."

'That's huge," says Fred Rothman, former chair of the Tax-Exempt

Organization at the American Institute for Certified Public Accountants.

"It's absolutely verboten to take money from the public to furnish a pri-

vate interest. And to not disclose is troubling-lit) begs the question,

'Why hide?'"

Praxis' accountants at the time, from the firm of Urbach, Kahn and

Werlin (who also handled the books and audits for the Dawn), say they

no longer do business with the organization and would not comment

on their audits.

Asked why restricted public funds were transferred into Zinsmeyer and

Duggins' private businesses, Amy Millard, an attorney for Praxis, would

only say in a written statement, "We've been cooperative with all investi-

gators and continue to do so. We're confident that it will be proven that

Mr. Zinsmeyer and Mr. Duggins have provided an important service to

the community and are dedicated towards the community they serve." She

did not return nwnerous phone calls for further comment.

It's a New York story from the beginning. Born in old-

line Texas, Glenn Sterling Zinsmeyer was outed for being gay at an early

age, he says, and lefr home as soon as possible. According to his reswne,

he graduated from the University of Texas, worked as a staffer in the

Kenyan parliament, and was later ordained as a minister at the Church

of Spiritual Science. (Asked if Zinsmeyer had ever graduated from the

University of Texas, the registrar there said he had not.)

When he moved to New York, he scarted working low-level jobs in

Chelsea bars and restaurants. As the AIDS epidemic grew in the gay

community, Zinsmeyer found new passion in activism and local politics.

In 1996, he became president of the Stonewall Democrats, a gay and les-

bian political club.

APRIL 2003

While Zinsmeyer was in college, Gordon Duggins was finishing up

at Duke University, and went on to earn two Master's degrees from Har-

vard Divinity School. He, too, grew up in the South, raised in Winston-

Salem, North Carolina.

Duggins trekked to Liberia, where he received his clergy papers. He

later settled in Bethlehem, Connecticut, where he continues to live in a

home complete with a private chapel, a $50,000 church organ and an

office for Woods Edge Resources, his consulting firm.

In the early 1990s, Duggins was hired as a fundraiser by Episcopal Social

Services (ESS), a 170-year-old social services group. It was there that he met

Zinsmeyer, who was running the organization's AIDS housing ptogram.

In the summer of 1995, with complementary skills for running and

raising money for AIDS housing, the pair decided to start their own

nonprofit, Praxis, Greek for "turning ideas into action."

ESS sponsored the idea, offering a $150,000 loan and free office

space to jumpstart operations. That relationship didn't last long, how-

ever. Only months into the operation, ESS' director, Father Steve Chin-

lund, resigned from the Praxis board. According to board minutes from

that time, he felt that the board had too many paid employees, which he

saw as a conflict. He severed ESS' official ties with the group. Chinlund

could not be reached for comment.

While still calling Praxis the "housing arm" ofESS in their newsletters,

Zinsmeyer, Duggins and a third director, Robert Peters, looked to raise

money, acquire shelters and get contracts from the city to house clients.

They occasionally resorted to desperate measures. In pulling together a

board of directors, they failed in some cases to get the permission of peo-

ple they claimed on paper as members. For example, Praxis' first city con-

tract lists Kenneth Lowry, director of Conflict Information and Dispute

Resolution, as a board member, a position he denies ever holding. "I'm

not on the board now and I never was," says Lowty.

Knowingly filing fulse informacion on city forms is a serious issue with

possible criminal repercussions, say city officials.

Meanwhile, Praxis struggled to get contracts. "We couldn't get anywhere

in City Hall," Peters recalls. "We needed to get our foot in the door."