Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Gender Wage Gap

Uploaded by

researchprof1Original Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Gender Wage Gap

Uploaded by

researchprof1Copyright:

Available Formats

Cohen, Philip and Matt Huffman. (2007). Working for the Woman?

Female Managers and the Gender Wage Gap, American Sociological Review, 72:5, 681-704. Taking a step away from traditional research on the subject, which was typically concerned with a womans access to high level managerial jobs and the traditional glass ceiling that seemed to prevent gender equality among managers, authors Cohen and Huffman provide a detailed analysis to ask different questions: do the gender characteristics of managers affect the inequality of non-managers reporting to them? The study itself was indeed exhaustive. The authors used U.S. Census data collected in 2002 from 79 major metropolitan labor markets across the span of 155 industries. They examined over 1.3 million records on workers to test their hypothesis. After analysis, their findings showed that as women advance into positions of greater authority, and have decision making impact on wage and mobility, the wage gap between genders declined. Women in managerial positions clearly help women, but they help men, too it seems that allowing women to influence hiring, firing and wage/human resource decisions makes for a more equitable workplace. A significant strength to this paper, too, is their review of the literature and their ability to effectively synthesize materials from wider studies to allow for incorporation into their own work. However, it was clear from the outset that several factors needed to be addressed prior to data collection and extrapolation. First, is there a difference in the way local and national industries utilize women managers? Can women even bridge the managerial gap or does gender inequality vary so widely amongst demographic areas that research between them is not comparable? Using studies from 2003 and 2004, the authors found that indeed, gender inequality varies systematically across larger markets, although now that there are more women in the

workplace, statistical analysis has more validity in comparing these markets while still taking into account industry type, size and age of the company, and general managerial responsibilities (See: Elliott and Smith, 2004, and; Hultin and Szulkin, 2003). Cohen and Huffman have taken several variables into consideration when exploring their questions. They have weighted industries that are typically male oriented, as well as underrepresented in past studies. They note, if female managers tend to cluster at the bottom of managerial hierarchies. Their mere representation in management may be insufficient to alter wage inequality(686). However, their basic data set is sound, and without its use it is unlikely a study of this kind would have been financially feasible. The basic data set is from the 2003 EEOC files, which are required filings by all private-sector businesses with 50 of more employees, or smaller firms if they are federal contractors. This data was analyzed at three conceptual levels: individual workers, jobs, and local industries. This data, combined with 2000 Census Public Use microdata, yielded a massive 1.32 million workers inside almost 30,000 local jobs, which in tern provided data on 1,318 local industries (687). Additionally, knowing that the title manager means different things at different levels and types of companies, they controlled for other important characteristics of local industries that could affect gender inequality. Among managers, we include managers as a percentage of all workers (689). Economic conditions were considered to capture aspects of more localized gender dynamics. For this data, the authors controlled the overall level of occupational gender segregation and the demand for female labor, using a standard index of dissimilarity (see Duncan, 1955). For the study to be rational, this economic index had to be used so that the association of earnings within different U.S. labor markets would tally with those in higher areas (e.g. some jobs pay $X for a restaurant manager in New York City, but $Y in Denver).

Copyright 2009 by Student Network Resources, Inc. For Research Purposes Only

Additionally, labor markets with higher levels of demand for female labor also have significantly less gender wage inequality (First proposed in Cotter, et.al., 1998). Additional significant analysis went into the variance components of wages, allowing the authors to analyze wages as three component parts of the data picture: 1. That which occurs between individuals and the mean wages in their jobs. 2. That which occurs between mean wages in each job and the mean wages for all jobs in their local industries. 3. That which occurs between the mean wages for local industries (701). For instance, this becomes crucial when trying to compare women in like jobs in unlike areas, but jobs that are variable enough that the wage is not truly reflective of the data set as a whole. Two particular examples of this show the level of detail in this research: 1) The difference between average wages for the restaurant industry versus the computer industry in a given market would be expected to be larger than differences between average wages in New York City and another major metropolitan area, and 2) The way women are concentrated in different areas, but similar industries, albeit different job levels, must also be acknowledged. An example of this is again in the restaurant industry: while percentages of women in the industry hold true across the United States, there are more women in upper management in the industry in eastern seaboard cities, making significantly higher wages without adjusting for this, the data set would not be accurate (698-9). The authors do acknowledge some flaws in their research, and take those flaws into consideration with their conclusion. In their data set, they were unable to link workers and managers in their actual work setting (700). Earlier studies found that as workplace processes sometimes naturally generate inequality, this variance changes across geographical and organizational settings (see Barron and Newman, 1990). In addition, by necessity, a large subset

Copyright 2009 by Student Network Resources, Inc. For Research Purposes Only

of data was absent due to the overwhelming amount of information, and difficulty thereof, to verify. Small businesses were excluded, as were some representative professions (education, for instance). While the upward mobility of women in these types of organizations may be, out of necessity, stronger, that data may suggest alternative conclusions. Still, there results are intrinsically sociological and broadly provocative and in line with the logical conclusion of much of the previous research (700). The findings in this study highlight, in a very analytical way, the importance of the term glass ceiling within the workplace. Qualified women are blocked from upper-level managerial positions, but their absence at the very top skews the curve when they are clustered in the middle. It seems that it takes about 30 percent penetration of women managers to begin to more rapidly move the distribution effect, suggesting that now, women remain concentrated in workplace settings with lower wages in almost every industry (699). This is a significant point when reviewing the type of research that has been done in the past decades and the strengths and weaknesses of said research1. If there is not a large enough sample to appropriately correlate, then the conclusions, while logical, may not pan out. Additionally, attitudinal and cultural changes over the past few decades have most certainly influenced gender gap behavior. However, while the hypothesis has been proven, there remains a great deal of inequity within the highest echelons of American management. For instance, as of 2007, only 13 women held top posts in Fortune 500 companies and only 1 runs a Fortune 50 enterprise. Women hold less than 20% of Board seats, even though that number has increased. And, when looking at average top-executive compensation, the CEO of Xerox (female) had the highest amount ($7.3million), but ranked only 225th. In addition, the average for a Fortune 500

1

For an interesting look at the history of womens roles over the past few decades, see: American Economic Gender Roles in Society, DVD, Quality Information Publishers, Inc. Copyright 2009 by Student Network Resources, Inc. For Research Purposes Only

CEO is $11million, so at this top level there is still some inequity. (See: Herrera, 2007). However, despite the fact that the percentages are still male oriented, the evolution at the very top is changing (See: Mero, 2008). Cohen and Huffman are more than thorough in their conclusions, their research metrology, and their adherence to detail. This is an important addition to the work already being done on the contribution of gender into American institutions. It fits well within the context of the literature on the interconnectedness of system stratification on gender inequality, and how that stratification almost perpetuates itself (see: Ore, 2008). Perhaps that is the next level of research now that we know that female managers positively affect the gender gap across the board, then now it is time to delve into more specific reasons for the continual gap at the top.

Copyright 2009 by Student Network Resources, Inc. For Research Purposes Only

References Baron, James and A. Newman. (1990). For What Its Worth: Organizations, occupations, and the Value of Work Done by Women and NonWhites. American Sociological Review. 55: 155-75. Cotter, David, et.al. (1997). All Women Benefit: The Macro Level Effect of Occupational Integration on Gender Earnings Inequality. American Sociological Review. 62: 714-34. Duncan, O.D. and B. (1955). A Methodological Analysis of Segregation Indexes. American Sociological Review. 20: 210-17. Elliott, James R. and Ryan Smith. (2004). Race, Gender, and Workplace Power. American Sociological Review. 48:547-61. Herrera, I.D. (2007). A Peaceful Revolution: Mind the Gap: The Female CEO. The Huffington Report, December 18, 2007. Cited in: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/irma-d-herrera/a-peaceful-revolution_b_77340.html. Hultin, Mia and R. Szulkin. (2003). Mechanisms of Inequality: Unequal Access to Organizational Power and the Gender Wage Gap. European Sociological Review. 19: 143-59. Mero, J. (2008). Fortune 500 Women CEOs. Fortune/CNNMoney.Com. Cited in: http://money.cnn.com/galleries/2008/fortune/0804/gallery.500_women_ceos.fortune/. Ore, Tracy. (2008). The Social Construction of Difference and Inequality. McGraw Hill.

Copyright 2009 by Student Network Resources, Inc. For Research Purposes Only

You might also like

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Iluminadores y DipolosDocument9 pagesIluminadores y DipolosRamonNo ratings yet

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Delegated Legislation in India: Submitted ToDocument15 pagesDelegated Legislation in India: Submitted ToRuqaiyaNo ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Branding Assignment KurkureDocument14 pagesBranding Assignment KurkureAkriti Jaiswal0% (1)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- 5Document3 pages5Carlo ParasNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Fix Problems in Windows SearchDocument2 pagesFix Problems in Windows SearchSabah SalihNo ratings yet

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Symptoms: Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD)Document3 pagesSymptoms: Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD)Nur WahyudiantoNo ratings yet

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Bodhisattva and Sunyata - in The Early and Developed Buddhist Traditions - Gioi HuongDocument512 pagesBodhisattva and Sunyata - in The Early and Developed Buddhist Traditions - Gioi Huong101176100% (1)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- English HL P1 Nov 2019Document12 pagesEnglish HL P1 Nov 2019Khathutshelo KharivheNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Emerging TechnologiesDocument145 pagesIntroduction To Emerging TechnologiesKirubel KefyalewNo ratings yet

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Assignment File - Group PresentationDocument13 pagesAssignment File - Group PresentationSAI NARASIMHULUNo ratings yet

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Consortium of National Law Universities: Provisional 3rd List - CLAT 2020 - PGDocument3 pagesConsortium of National Law Universities: Provisional 3rd List - CLAT 2020 - PGSom Dutt VyasNo ratings yet

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Eradication, Control and Monitoring Programmes To Contain Animal DiseasesDocument52 pagesEradication, Control and Monitoring Programmes To Contain Animal DiseasesMegersaNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Executive SummaryDocument3 pagesExecutive SummarySofia ArissaNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Img - Oriental Magic by Idries Shah ImageDocument119 pagesImg - Oriental Magic by Idries Shah ImageCarolos Strangeness Eaves100% (2)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- GooseberriesDocument10 pagesGooseberriesmoobin.jolfaNo ratings yet

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Phylogenetic Tree: GlossaryDocument7 pagesPhylogenetic Tree: GlossarySab ka bada FanNo ratings yet

- Book TurmericDocument14 pagesBook Turmericarvind3041990100% (2)

- You Are The Reason PDFDocument1 pageYou Are The Reason PDFLachlan CourtNo ratings yet

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Rajasekhara Dasa - Guide To VrindavanaDocument35 pagesRajasekhara Dasa - Guide To VrindavanaDharani DharendraNo ratings yet

- Rudolf Steiner - Twelve Senses in Man GA 206Document67 pagesRudolf Steiner - Twelve Senses in Man GA 206Raul PopescuNo ratings yet

- Manalili v. CA PDFDocument3 pagesManalili v. CA PDFKJPL_1987100% (1)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- 1INDEA2022001Document90 pages1INDEA2022001Renata SilvaNo ratings yet

- DBT Cope Ahead PlanDocument1 pageDBT Cope Ahead PlanAmy PowersNo ratings yet

- Advanced Financial Accounting and Reporting Accounting For PartnershipDocument6 pagesAdvanced Financial Accounting and Reporting Accounting For PartnershipMaria BeatriceNo ratings yet

- Oral Oncology: Jingyi Liu, Yixiang DuanDocument9 pagesOral Oncology: Jingyi Liu, Yixiang DuanSabiran GibranNo ratings yet

- Green and White Zero Waste Living Education Video PresentationDocument12 pagesGreen and White Zero Waste Living Education Video PresentationNicole SarileNo ratings yet

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Aqualab ClinicDocument12 pagesAqualab ClinichonyarnamiqNo ratings yet

- Boot CommandDocument40 pagesBoot CommandJimmywang 王修德No ratings yet

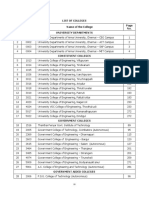

- TNEA Participating College - Cut Out 2017Document18 pagesTNEA Participating College - Cut Out 2017Ajith KumarNo ratings yet

- 30rap 8pd PDFDocument76 pages30rap 8pd PDFmaquinagmcNo ratings yet

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)