Professional Documents

Culture Documents

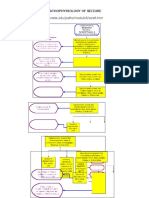

Pathophysiology Schistosomiasis: Table in New Window

Uploaded by

Karen Leigh MagsinoOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Pathophysiology Schistosomiasis: Table in New Window

Uploaded by

Karen Leigh MagsinoCopyright:

Available Formats

Pathophysiology Schistosomiasis

Human beings become infected when larval forms of the parasite, released by freshwater snails, penetrate their skin during contact with infested water. In the body, the larvae develop into adult schistosomes. Adult worms live in the blood vessels, where the females release eggs. Some of the eggs are passed out of the body in the feces or urine to continue the parasite life-cycle. Others become trapped in body tissues, causing an immune reaction and progressive damage to organs. Two major forms of schistosomiasis exist: intestinal and urogenital. These are caused by 5 main species. Table 1. Parasite Species and Geographical Distribution of Schistosomiasis2,7 Open table in new window Species Intestinal schistosomiasis Geographical distribution Schistosoma mansoni Africa, the Middle East, the Caribbean, South (mesenteric venules of the America colon) Schistosoma japonicum (mesenteric venules of the small intestine) Schistosoma mekongi (mesenteric venules of the small intestine) Asia only: China, Indonesia, the Philippines and Thailand Several districts of Cambodia and the Lao Peoples Democratic Republic. 200-km area of Mekong river basin; now extending toward northern provinces

Schistosoma intercalatum Rain forest areas of Central and West Africa (mesenteric venules of the colon) and related S guineansis Urogenital schistosomiasis Schistosoma haematobium (vesical venous plexus) Africa, the Middle East, India, Turkey

The pathophysiology of infection correlates with the life cycle of the parasite. Cercariae Skin penetration of cercariae produces an allergic dermatitis at the site of entry. With prior sensitization, a pruritic papular rash develops. This also is observed with nonhuman avian schistosomes. Schistosomula These are tailless cercariae that are transported through blood or lymphatics to the right side of the heart and lungs. Heavy infection can cause symptoms such as cough and fever. Eosinophilia may be observed.

Adult worm Adult worms do not multiply inside the human body. In the venous blood, adult male and female worms mate, and the female lays eggs 4-6 weeks after cercarial penetration. Adult worms are rarely pathogenic. The female adult worm lives for approximately 3-8 years and lays eggs throughout her life span. The life cycle of the flatworms in the genus Schistosoma, within the class Trematode, that cause human schistosomiasis involves a sexual stage in the human and an asexual stage in the freshwater snail host. The adult worms are small, 12-26 mm long and 0.3-0.6 mm wide, and vary with the different species. Adult worms mate and lay eggs. The eggs are nonoperculate, possess a spine, and contain a miracidium. The microscopic appearance of the egg allows diagnostic differentiation of the 5 species. An adult S hematobium produces 20-200 round, terminally spined eggs per day; S mansoni produces 100-300 ovoid, laterally spined eggs per day; and S japonicum produces 500-3500 round, small, laterally spined eggs per day. The eggs of S intercalatum have prominent terminal spines, and S mekongi have small lateral spines. When the ova reach the fresh water, the miracidia are released and penetrate the snail. Within 35 weeks, they asexually multiply into hundreds of fork-tailed cercariae. The cercariae leave the snail and swim to a human or nonhuman animal, where they penetrate the skin. Once inside, cercariae travel to the heart, to the lungs, and through the systemic circulation to reach the portal veins, where they develop into adult worms. The time between cercariae penetration and the first ova production is 4-6 weeks. Humans are estimated to excrete approximately 50% of the eggs. The rest are trapped in various parts of the body. Occasionally, the worm can be in ectopic positions, such as in the spinal cord, where it produces unusual clinical manifestations. Eggs Eggs cause Katayama fever and schistosomiasis. Katayama fever: The exact pathophysiology is not known. It occurs 4-6 weeks after infection, at the time of the initial egg release. It is reported most commonly with S japonicum but also has been reported with S mansoni.Katayama fever is believed to be due to the high worm and egg antigen stimuli that result from immune complex formation and lead to a serum sicknesslike illness. This syndrome is not due to granuloma formation. Schistosomiasis: It is due to immunological reactions to Schistosoma eggs trapped in tissues. Antigens released from the egg stimulate a granulomatous reaction comprised of T cells, macrophages, and eosinophils that results in clinical disease. Symptoms and signs depend on the number and location of eggs trapped in the tissues. Initially, the inflammatory reaction is readily reversible. In the latter stages of the disease, the pathology is associated with collagen deposition and fibrosis, resulting in organ damage that may be only partially reversible.

Granuloma in the liver due to Schistosoma mansoni. The S mansoni egg is at the center of the granuloma.

Eggs can end up in the skin, brain, muscle, adrenal glands, and eyes. As the eggs penetrate the urinary system, they can find their way to the female genital region and form granulomas in the uterus, fallopian tube, and ovaries. CNS involvement occurs because of embolization of eggs from the portal mesenteric system to the brain and spinal cord via the paravertebral venous plexus.11,12 One male or female miracidium occurs in excreted eggs. Miracidium is an immature larval form. These go onto a susceptible snail intermediate host. The different species of Schistosoma have different types of snails, which serve as their intermediate hosts, as follows:7,13,14 Biophalaria for S mansoni Oncomelania for S japonicum Tricula (Neotricula aperta) for S mekongi Bulinus for S haematobium and S intercalatum

Pathophysiology

Adult worms live and copulate within the veins of the mesentery (typically S. japonicumand S. mansoni) or bladder (typically S. haematobiumsee Fig. 1: Trematodes (Flukes): Simplified Schistosoma life cycle. ). Some eggs penetrate the intestinal or bladder mucosa and are passed in stool or urine; other eggs remain within the host organ or are transported through the portal system to the liver and occasionally to other sites (eg, lungs, CNS, spinal cord). Excreted eggs hatch in freshwater, releasing miracidia (first larval stage), which enter snails. After multiplication, thousands of free-swimming cercariae are released. Cercariae penetrate human skin within a few minutes after exposure and transform into schistosomula, which travel through the bloodstream to the liver, where they mature into adults. The adults then migrate to their ultimate home in the intestinal veins or the venous plexus of the GU tract. Eggs appear in stool or urine 1 to 3 mo after cercarial penetration.

Estimates of the adult worm life span range from 3 to 7 yr. The females range in size from 7 to 20 mm; males are slightly smaller.

Fig. 1

Simplified Schistosoma life cycle.

1. In the human host, eggs containing miracidia are eliminated with feces or urine into water. 2. In water, the eggs hatch and release miracidia. 3. The miracidia swim and penetrate a snail (intermediate host). 4. Within the snail, the miracidia progress through 2 generations of sporocysts to cercariae. 5. The free-swimming cercariae are released from the snail and penetrate the skin of the human host. 6. During penetration, the cercariae lose their forked tail, becoming schistosomula. The schistosomula are transported through the vasculature to the liver; there, they mature into adults.

7. The paired (male and female) adult worms migrate (depending on their species) to the intestinal veins in the bowel or rectum or to the venous plexus of the GU tract, where they reside and begin to lay eggs.

Pathophysiology

Life cycle

Schistosoma life cycle. Source: CDC

Schistosomes have a typical trematode vertebrate-invertebrate lifecycle, with humans being the definitive host.

Snails

The life cycles of all five human schistosomes are broadly similar: parasite eggs are released into the environment from infected individuals, hatching on contact with fresh water to release the free-swimming miracidium. Miracidia infect fresh-water snails by penetrating the snail's foot. After infection, close to the site of penetration, the miracidium transforms into a primary (mother) sporocyst. Germ cells within the primary sporocyst will then begin dividing to produce secondary (daughter) sporocysts, which migrate to the snail's hepatopancreas. Once at the hepatopancreas, germ cells within the secondary sporocyst begin to divide again, this time producing thousands of new parasites, known as cercariae, which are the larvae capable of infecting mammals. Cercariae emerge daily from the snail host in a circadian rhythm, dependent on ambient temperature and light. Young cercariae are highly mobile, alternating between vigorous upward movement and sinking to maintain their position in the water. Cercarial activity is particularly stimulated by water turbulence, by shadows and by chemicals found on human skin.

Humans

Penetration of the human skin occurs after the cercaria have attached to and explored the skin. The parasite secretes enzymes that break down the skin's protein to enable penetration of the

cercarial head through the skin. As the cercaria penetrates the skin it transforms into a migrating schistosomulum stage.

Photomicrography of bladder in S. hematobium infection, showing clusters of the parasite eggs with intense eosinophilia, Source: CDC

The newly transformed schistosomulum may remain in the skin for 2 days before locating a postcapillary venule; from here the schistosomulum travels to the lungs where it undergoes further developmental changes necessary for subsequent migration to the liver. Eight to ten days after penetration of the skin, the parasite migrates to the liver sinusoids. S. japonicum migrates more quickly than S. mansoni, and usually reaches the liver within 8 days of penetration. Juvenile S. mansoni and S. japonicum worms develop an oral sucker after arriving at the liver, and it is during this period that the parasite begins to feed on red blood cells. The nearly-mature worms pair, with the longer female worm residing in the gynaecophoric channel of the shorter male. Adult worms are about 10 mm long. Worm pairs of S. mansoni and S. japonicum relocate to the mesenteric or rectal veins. S. haematobium schistosomula ultimately migrate from the liver to the perivesical venous plexus of the bladder, ureters, and kidneys through the hemorrhoidal plexus. Parasites reach maturity in six to eight weeks, at which time they begin to produce eggs. Adult S. mansoni pairs residing in the mesenteric vessels may produce up to 300 eggs per day during their reproductive lives. S. japonicum may produce up to 3000 eggs per day. Many of the eggs pass through the walls of the blood vessels, and through the intestinal wall, to be passed out of the body in feces. S. haematobium eggs pass through the ureteral or bladder wall and into the urine. Only mature eggs are capable of crossing into the digestive tract, possibly through the release of proteolytic enzymes, but also as a function of host immune response, which fosters local tissue ulceration. Up to half the eggs released by the worm pairs become trapped in the mesenteric veins, or will be washed back into the liver, where they will become lodged. Worm pairs can live in the body for an average of four and a half years, but may persist up to 20 years.

Trapped eggs mature normally, secreting antigens that elicit a vigorous immune response. The eggs themselves do not damage the body. Rather it is the cellular infiltration resultant from the immune response that causes the pathology classically associated with schistosomiasis. News medical.net The cercariae of the parasite penetrate the skin, migrate to the liver via the lungs, and remain in the intrahepatic portal venules until the worm matures. The mature worm, which does not multiply within humans, then moves into its final habitat. Depending on the species involved, the worm may settle in the veins of the large bowel, small bowel, or bladder where it lays its eggs. These eggs, which form pseudotubercules(small, knobby prominences), have been found in every system in the body. Schistosomiasis may have mild or severe manifestations, depending on the species of worms involved and the number present. Laboratory studies to identify the species are completed before pharmacologic treatment with oxamniquine, metrifonate, praziquantel or niridazole is started.

You might also like

- DB13 - Pathophysiology of AtherosclerosisDocument2 pagesDB13 - Pathophysiology of Atherosclerosisi_vhie03No ratings yet

- Case Presentation OsteomylitisDocument64 pagesCase Presentation OsteomylitisDemi Rose Bolivar100% (1)

- Electrolyte Imbalance 1Document3 pagesElectrolyte Imbalance 1Marius Clifford BilledoNo ratings yet

- Case AnalysisDocument12 pagesCase AnalysisFroilan TaracatacNo ratings yet

- BPH Pathophysio 4CDocument2 pagesBPH Pathophysio 4CPatricia Camille Ponce JonghunNo ratings yet

- Paroxysmal Nocturnal Hemoglobinuria Case StudyDocument87 pagesParoxysmal Nocturnal Hemoglobinuria Case Studyrachael100% (4)

- ABRUPTIO PLACENTAE PathophysiologyDocument3 pagesABRUPTIO PLACENTAE PathophysiologyBarda GulanNo ratings yet

- Stomach Cancer Print EditedDocument6 pagesStomach Cancer Print EditedSyazmin KhairuddinNo ratings yet

- NCP - Poststreptococcal GlomerulonephritisDocument12 pagesNCP - Poststreptococcal GlomerulonephritisAya BolinasNo ratings yet

- Pathophysiology Acute Pyelonephriti1Document2 pagesPathophysiology Acute Pyelonephriti1Stephanie Joy EscalaNo ratings yet

- Anatomy and Physiology PneumoniaDocument4 pagesAnatomy and Physiology PneumoniaJohnson MallibagoNo ratings yet

- CholelithiasisDocument3 pagesCholelithiasisMIlanSagittarius0% (1)

- Case Study in KidneyDocument3 pagesCase Study in KidneyVenice VelascoNo ratings yet

- Hemorrhagic Cerebro Vascular DiseaseDocument37 pagesHemorrhagic Cerebro Vascular Diseasejbvaldez100% (1)

- Pahtophysiology of EsrdDocument5 pagesPahtophysiology of EsrdCarl JardelezaNo ratings yet

- Parapneumonic Pleural Effusions and Empyema Thoracis - Background, Pathophysiology, EpidemiologyDocument4 pagesParapneumonic Pleural Effusions and Empyema Thoracis - Background, Pathophysiology, EpidemiologyLorentina Den PanjaitanNo ratings yet

- Hiv Case StudyDocument2 pagesHiv Case Studyapi-485814878No ratings yet

- AmoebiasisDocument1 pageAmoebiasisYakumaNo ratings yet

- Gastric AdenocarcinomaDocument4 pagesGastric AdenocarcinomaJimel Vital Carreon100% (2)

- Nephrotic Syndrome PathophysiologyDocument1 pageNephrotic Syndrome PathophysiologyKrisianne Mae Lorenzo FranciscoNo ratings yet

- Addison'sDocument4 pagesAddison'sKoRnflakesNo ratings yet

- Parapneumonic Pleural Effusion and EmpyemaDocument8 pagesParapneumonic Pleural Effusion and EmpyemaWin ThuNo ratings yet

- Schistosomiasis (From Anatomy To Pathophysiology)Document10 pagesSchistosomiasis (From Anatomy To Pathophysiology)Tiger Knee100% (1)

- Post-Streptococcal GlomerulonephritisDocument18 pagesPost-Streptococcal GlomerulonephritisPreciousJemNo ratings yet

- Factors: AffectingDocument23 pagesFactors: AffectingAmeerah Mousa KhanNo ratings yet

- Vii. Pathophysiology A. AlgorithmDocument2 pagesVii. Pathophysiology A. AlgorithmJonna Mae TurquezaNo ratings yet

- Scribd 020922 Case Study-Oncology A&kDocument2 pagesScribd 020922 Case Study-Oncology A&kKellie DNo ratings yet

- Thinking UpstreamDocument1 pageThinking UpstreamDONITA DALUMPINESNo ratings yet

- CholecystitisDocument12 pagesCholecystitisMariela HuertaNo ratings yet

- Ebola Virus DiseaseDocument19 pagesEbola Virus DiseaseAuliani Annisa FebriNo ratings yet

- Hepatobiliary SystemDocument35 pagesHepatobiliary Systemyoyo patoNo ratings yet

- Pathophysiology of SeizuresDocument2 pagesPathophysiology of SeizuresireneNo ratings yet

- Acute Lymphocytic LeukemiaDocument12 pagesAcute Lymphocytic Leukemiajustin_saneNo ratings yet

- Pathophysiology of Hypertension, Diabetes, Ubm, BPHDocument3 pagesPathophysiology of Hypertension, Diabetes, Ubm, BPHCarly Beth Caparida LangerasNo ratings yet

- Pa Tho Physiology of TuberculosisDocument3 pagesPa Tho Physiology of TuberculosisFlauros Ryu JabienNo ratings yet

- Pamantasan NG Cabuyao College of Health Allied Sciences College of NursingDocument43 pagesPamantasan NG Cabuyao College of Health Allied Sciences College of NursingSofea MustaffaNo ratings yet

- Pa Tho Physiology of PneumoniaDocument6 pagesPa Tho Physiology of PneumoniaPaula YoungNo ratings yet

- The Infectious ProcessDocument4 pagesThe Infectious ProcessAdnan Akram, MD (Latvia)100% (1)

- HyperkalemiaDocument10 pagesHyperkalemiaAdrian MallarNo ratings yet

- Pathophysiology of DiarrheaDocument3 pagesPathophysiology of DiarrheaFathur RahmatNo ratings yet

- Pathophysiology of AmoebiasisDocument1 pagePathophysiology of AmoebiasisCathy AcquiatanNo ratings yet

- Liver AbscessDocument6 pagesLiver AbscessKenneth SunicoNo ratings yet

- Pathophysiology of Urinary Tract ObstructionDocument50 pagesPathophysiology of Urinary Tract ObstructionPryo UtamaNo ratings yet

- What Is A Communicable DiseaseDocument3 pagesWhat Is A Communicable DiseaseChrisel D. SamaniegoNo ratings yet

- Pathophysiology: Non-Hodgkin's LymphomaDocument1 pagePathophysiology: Non-Hodgkin's LymphomaExernest Joever ZausaNo ratings yet

- Pathognomonic Signs of Communicable Diseases: JJ8009 Health & NutritionDocument2 pagesPathognomonic Signs of Communicable Diseases: JJ8009 Health & NutritionMauliza Resky NisaNo ratings yet

- BioethicsCasesEEI 316232215 PDFDocument38 pagesBioethicsCasesEEI 316232215 PDFAman UllahNo ratings yet

- Multiple Physical Injuries Secondary To Vehicular AccidentDocument31 pagesMultiple Physical Injuries Secondary To Vehicular AccidentJane Arian BerzabalNo ratings yet

- PATHOPHYSIO (Megaloblastic Anemia)Document3 pagesPATHOPHYSIO (Megaloblastic Anemia)Giselle EstoquiaNo ratings yet

- Hypertension Pathophysiology and Treatment PDFDocument6 pagesHypertension Pathophysiology and Treatment PDFBella TogasNo ratings yet

- PT EducationDocument4 pagesPT Educationapi-248017509No ratings yet

- Influenza PATHOPHYSIOLOGYDocument3 pagesInfluenza PATHOPHYSIOLOGYElle RosalesNo ratings yet

- Community Acquired Pneumonia, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsFrom EverandCommunity Acquired Pneumonia, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsNo ratings yet

- Hirschsprung’s Disease, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsFrom EverandHirschsprung’s Disease, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsNo ratings yet

- Schistosomes: Diecious TrematodesDocument6 pagesSchistosomes: Diecious TrematodesShivanshi KNo ratings yet

- Blood Flukes Life CycleDocument5 pagesBlood Flukes Life CyclePratita Ayu PinasthikaNo ratings yet

- SchistosomiasisDocument12 pagesSchistosomiasisHarold Jake ArguellesNo ratings yet

- Parasitology Trematodes S. JaponicumDocument48 pagesParasitology Trematodes S. JaponicumNicole ManogNo ratings yet

- Rebecca Hebner Humbio 153 Parasites and Pestilence Parasite: Schistosoma MekongiDocument32 pagesRebecca Hebner Humbio 153 Parasites and Pestilence Parasite: Schistosoma MekongiJan DielNo ratings yet

- Protein Electrophoresis - Clinical DiagnosisDocument415 pagesProtein Electrophoresis - Clinical Diagnosissssahilz100% (2)

- A D W A ADocument2 pagesA D W A Akemet215No ratings yet

- Anthony The Horse, The Wheel, and Language, CH 1Document19 pagesAnthony The Horse, The Wheel, and Language, CH 1Diana BujaNo ratings yet

- Containing The Crisis Zine PDFDocument36 pagesContaining The Crisis Zine PDFHearst LeeNo ratings yet

- Contemp World Quiz 4Document9 pagesContemp World Quiz 4CJ PLATONNo ratings yet

- 11 Global MigrationDocument10 pages11 Global MigrationLeah Campollo100% (2)

- Richter Et Al 2012Document20 pagesRichter Et Al 2012HULIOSMELLANo ratings yet

- GlobalizationDocument4 pagesGlobalizationSudeep Bir TuladharNo ratings yet

- Field Guide To Boises Birds 101415Document58 pagesField Guide To Boises Birds 101415Leanne JuddNo ratings yet

- Steven M. Baule - : Drummers in The British Army During The American RevolutionDocument14 pagesSteven M. Baule - : Drummers in The British Army During The American RevolutionJohn U. Rees100% (1)

- Threshold 7Document250 pagesThreshold 7Eric Rumfelt100% (5)

- EricDocument3 pagesEricMaine BasanNo ratings yet

- Illegal Migration Into Assam Magnitude Causes andDocument46 pagesIllegal Migration Into Assam Magnitude Causes andManan MehraNo ratings yet

- Bodies Border Sex Work PDFDocument279 pagesBodies Border Sex Work PDFMaría José Gutiérrez JiménezNo ratings yet

- Oracle To MySQL ConversionDocument15 pagesOracle To MySQL Conversionmohd_sajjad25No ratings yet

- Gannenmono Journey: Key DatesDocument1 pageGannenmono Journey: Key DatesHonolulu Star-AdvertiserNo ratings yet

- SlumDocument28 pagesSlumakanksharaj90% (1)

- 2010migration and The GulfDocument93 pages2010migration and The GulfAsinitas OnlusNo ratings yet

- Migrants Suffering Violence While in Transit Through Mexico: Factors Associated With The Decision To Continue or Turn BackDocument9 pagesMigrants Suffering Violence While in Transit Through Mexico: Factors Associated With The Decision To Continue or Turn BackGlennKesslerWPNo ratings yet

- Contemporary World Pre-Final ExamDocument7 pagesContemporary World Pre-Final ExamAce Shernyll Son GallanoNo ratings yet

- Electrodes and PotentiometryDocument26 pagesElectrodes and PotentiometryMegha AnandNo ratings yet

- Scope of WorkDocument6 pagesScope of WorkOneil SalmonNo ratings yet

- Re-Populating Rural Studies Migrations, Movements and MobilitiesDocument6 pagesRe-Populating Rural Studies Migrations, Movements and Mobilitiesnyinyi66No ratings yet

- Requirements For A Tourist, Visitor, Business, Event and Honeymoon VisaDocument2 pagesRequirements For A Tourist, Visitor, Business, Event and Honeymoon VisaAditya ShrivastavaNo ratings yet

- African American LiteratureDocument16 pagesAfrican American LiteratureBala Tvn100% (1)

- Sedimenatary Structures Syn DepositionalDocument13 pagesSedimenatary Structures Syn DepositionalChristian MoraruNo ratings yet

- 21: Bone Wound Healing and OsseointegrationDocument15 pages21: Bone Wound Healing and OsseointegrationNYUCD17No ratings yet

- Hoffmann, R., Šedová, B., & Vinke, K. (2021) - Improving The Evidence Base - A Methodological Review of The Quantitative Climate Migration LiteratureDocument14 pagesHoffmann, R., Šedová, B., & Vinke, K. (2021) - Improving The Evidence Base - A Methodological Review of The Quantitative Climate Migration LiteratureValquiria AlmeidaNo ratings yet

- 04 - Streamline English - DestinationsDocument46 pages04 - Streamline English - DestinationsThoLe100% (1)

- BelayneehDocument87 pagesBelayneehmollaselamuNo ratings yet