Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Top Secret - The Chinese Envoy's Briefing Paper On The Economic Outlook For The Great Southern Province of China by Satyajit Das

Uploaded by

api-90504428Original Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Top Secret - The Chinese Envoy's Briefing Paper On The Economic Outlook For The Great Southern Province of China by Satyajit Das

Uploaded by

api-90504428Copyright:

Available Formats

australia-southernprovinceofchina(dec2011)

Top Secret - The Chinese Envoys Briefing Paper On The Economic Outlook for the Great Southern Province of China by Satyajit Das Your Excellency, I am pleased to present the requested report on the economic outlook for the Great Southern Province of China, currently referred to by the local population as Australia. For convenience I will refer to the country by this older name. Deep dependence on our great nation means Australias future is inextricably linked to China. Given that the white European colonisers historically feared the yellow peril, the irony of the situation will be not lost on the Politburo. Despite recent engagement with us and the rest of Asia, Australias focus seems confused. The countrys head of state remains an octogenarian British Queen. Australia also believes its security is guaranteed by the United States of America with whom it has extensive defence links. The locals continue to believe in both in its sovereignty and also its bright economic prospects. Escaping Acronyms The popular narrative is that Australia escaped the GFC (global financial crisis the locals are acronymic) through their own planning. The country was certainly in a better position to cope with the problems. The Federal government did not have much debt. However, some State governments have significant borrowing. Governments also systematically shifted some of their debt into public private partnerships (PPP). Because of the strategic nature of this infrastructure, these projects de facto enjoy the indirect support of governments. Private household debt is also high. At the start of the crisis, Australian interest rates were relatively high, providing greater flexibility. But Australia did not escape the crisis unscathed. One major bank lost nearly a billion Aussies (colloquial term for the Australian dollar, the local version of the Renminbi). Investors, including a number of charities and local councils, suffered significant losses from investments in various financial products. A number of highly leveraged infrastructure and commercial real-estate investors failed. Local banks escaped the problems of their overseas counterparts. The near death experiences in the recession of the early 1990s encouraged them to stay home eschewing overseas adventures and complex financial structures. That said, another year or so, they would not have been so lucky. The local banking regulator, APRA (Australian Prudential Regulation Authority), and politicians take credit for the banks being relatively unaffected. This is curious given that banking regulations are largely uniform around the world. One can only assume that Australia has superior regulators and politicians to the rest of the world an example of Australian exceptionalism. In reality, Australias swift recovery was driven by large cuts in interest rates, government guarantees for banks, government stimulus and a commodity boom. The central bank reduced interest rates (from 7.25% per annum to 3.00% per annum). The fall of 4.25% per annum translates into a fall in monthly mortgage repayments of nearly 30 % or around $7,000 per year on a 20-year mortgage of $250,000. A government guarantee on bank deposits and borrowing ensured that financial institutions were insulated from many of the problems. Government spending minimised the effects on the real economy. Cleverly directed cash transfers to lower income households rapidly stimulated the economy. As part of the ESP (Economic Stimulus Package), government spending on education, housing and infrastructure was also increased. Some of the spending was not well directed. Environmental initiatives, subsidies for home insulation to reduce energy consumption, have proved less than successful.

2012 Satyajit Das

Page 1 of 8

australia-southernprovinceofchina(dec2011)

The long-term benefit of some spending is questionable. Your Excellency, the school across from my office has been refurbished with new gold signage and a brand new fence replacing the aluminium one that was perfectly serviceable. The economic return on this investment is unknown. The main driver of the recovery has been a commodity boom. This is not a new phenomenon in Australian history. It can be traced back to the famous gold rush of the 19th century when many of our countrymen travelled to Australia in search of their fortunes. Boom Former Prime Minister of Australia Paul Keating, a prominent Sino-phile, recently remarked that Australians were luckier than most races having been give an entire continent. He might have added that it was also remarkably rich in mineral wealth. Australia has benefited from a substantial increase in demand for and prices for its mineral products. The country is enjoying its best terms of trade (measured as Price of Exports divided by Price of Imports, showing the quantity of imports that can be purchased theoretically from the sale of a fixed amount of exports) in 140 years. Australias terms of trade have improved by 42%, just since 2004. The commodity boom is driven by a sharp increase in demand, supply constraints because of underinvestment in mineral production and associated infrastructure and some unexpected effects of the GFC. In the 1990s, as a result of persistently low prices, mining companies did not invest sufficiently in expanding production capacity or infrastructure, such as transport, refining or processing capacity. The increase in demand from purchasers, particularly emerging economies, quickly created bottlenecks and shortages. This led to sharply higher prices as well as improved volumes for many commodities. The GFC also boosted investment in commodities. As traditional investments fared poorly (stocks, interest rates and property prices all fell), investors switched to hard assets, like commodities. The underlying logic was that these were real assets with genuine underlying uses rather than the fictions created through financial engineering. Low interest rates also assisted demand and prices as it cost less than before to buy and hold commodities, which paid no return. As central banks commenced printing money in an effort to restart growth, investment in commodities increased further as investors sought a hedge against the risk of inflation. Former Board member of the Reserve Bank of Australia, Professor Russell McKibbin suggested that perhaps as much as 40% of the improvement in Australias terms of trade was driven by US and European monetary expansion. As your Excellency knows, one of Chinas priorities is to preserve the value of its foreign exchange reserves, currently around US$3.2 trillion. The bulk of these funds are invested in US dollar, Euro and Yen denominated securities. To reduce the risk of losses as these securities lose value due to the actions of governments to devalue the currency against the Renminbi, we have executed your instruction to purchase and stockpile large amounts of strategic commodities. Boomier The economists, who failed to forecast the rise in commodity prices or the GFC, now speak of a super boom lasting decades. The boom is more fragile than currently understood. As growth in China and other emerging countries decelerates, demand for commodities is likely to slow. High prices have encouraged investment in expanding existing mines, building new mines and additional infrastructure as well as exploration. As new capacity and supply comes on stream, there will be pressure on prices.

2012 Satyajit Das

Page 2 of 8

australia-southernprovinceofchina(dec2011)

At your Excellencys suggestion, we have extensively studied the commodity purchasing strategies of Japan in the 1980s. Based on this analysis, we have actively cultivated new sources of supply of essential commodities. This will enable us to play suppliers off against each other to achieve more favourable prices in the long term. Westerners place great store in contracts, such as long term agreements to purchase minerals at agreed prices. In the Chinese way, these are, at best, statements of intention based on conditions existing at the time of agreement. If conditions change, then we will, like the Japanese, renegotiate the arrangements in our favour. Australian mining entrepreneurs and politicians point to a massive pipeline of projects, which will underpin Australian prosperity. The Australian Mines and Metals Association estimate that there is A$427 billion of resources in train, including A$146 billion in Liquid Natural Gas alone. A$236 billion of projects are current under way with a further A$191 billion awaiting approval. There is also A$770 billion of infrastructure spending required to renew and develop Australias economic and social infrastructure. This will compete with commodity projects for funding. Chairman of Infrastructure Australia Rod Eddington has warned that financing will not be available for many projects. Infrastructure Australia has identified a smaller list of priority project totalling A$86 billion. Commodity projects depend on demand for the product and also on the ability to finance it. Deterioration in money market conditions and also problems in the banking system mean that the availability of funding is becoming more restricted and expensive. If previous commodity booms are a guide, then many of these projects may not eventuate. Sinophilia Around 23 % of Australian exports now go to China. The real quantum is higher as some Australian exports to Asia are then re-exported to China. China currently faces significant challenges. Our two major trading partner Europe and America face serious problems which will lead to a slow down in our own exports. Recent statistics, such as the volatile Purchasing Managers Index that measures manufacturing activity, suggest a sharp slowdown. In turn, this will affect our suppliers such as Australia by way of lower demand and also lower prices for commodities. Unlike 2008, our capacity to respond to any slowdown is reduced. Then, we increased lending through our policy banks to boost demand. In 2009 and 2010, we were able to grow loans by around 30-40% of our GDP to drive growth. Unfortunately, party cadres have not used the money wisely in all cases, resulting in some unproductive investment and bad debts for the banks. The need to support our banks and cover their bad debts will restrict our ability to support the economy. As your excellency is also aware, around US$ 800 billion or 25% of our US$3.2 trillion in foreign exchange reserves is invested in risk free European government bonds. Continued losses in these investments and on investments in US government bonds also further restrict our flexibility. Our economic growth will be slower then widely anticipated. European Tsunamis Australians believe that physical distance from Europe and proximity to China and Asia affords protection from European debt problems. Despite record terms of trade and high export volumes, Australia continues to run a current account deficit with the rest of the world of around 2-3% of GDP, around US$30-40 billion per year. This must be financed overseas. Sovereign debt problems and the resultant problems in the banking system will affect international money markets for some time to come. Australian borrowers will face reduced availability of funding and increased borrowing cost. Before the crisis, Australian bank deposits totalled 50-60% of loans made. The difference was funded in wholesale markets, generally from institutional investors.

2012 Satyajit Das

Page 3 of 8

australia-southernprovinceofchina(dec2011)

In 2007, deposits made up around 20% of bank borrowing down from 34% a decade earlier. Domestic wholesale borrowing and foreign wholesale borrowing were 53% and 27% of bank balance sheets. Following the GFC, increases in the cost of overseas funding and regulatory pressure, Australian banks significantly reduced their loan to deposit ratios, with deposits now around 70% of loans. They also reduced their dependence on international borrowings. Nevertheless, Australian banks face significantly international re-financing pressures, needing around A$80 billion in 2012. Around A$35 billion are AAA rated government guaranteed bonds which will need to be financed without government support, unless the policy changes. In addition, the banks have a further A$28 billion worth of bonds that mature in the domestic markets In the period before the GFC, Australian banks relied on securitisation to raise cheap funding from overseas. When these markets closed, Australian banks used debt guaranteed by the Federal Government to raise funds. With the guarantee now not available, Australian banks are increasingly using covered bonds to raise funds. Covered bonds are secured over specified assets such as a pool of mortgages, giving investors priority over depositors. Regulators have limited the quantum of covered bonds permitted to a maximum of 8% of assets, limiting the ability of banks to use this form of financing. To date, covered bonds have not proved a cheap source of finance for banks, as originally envisaged. Inaugural international issues by ANZ and Wespac have cost around 1.50% over inter-bank rates. In early 2012, the Commonwealth Bank issued at around 1.75% over interbank rates in the domestic markets. Given that the covered bonds enjoyed the highest rating of AAA, the funding cost for Australian banks for unsecured borrowings would be around 2.00-2.50% over inter-bank rates, a sharp increase over the last 6 months. This higher cost will be passed on to customers at some stage. In testimony to a parliamentary committee, John Laker, the head of APRA, acknowledged the funding challenge. He hoped that improvements in market conditions would allow the Australian banks to access the overseas funding required. Money Too Tight To Mention Facing reduced availability and higher cost of funding, Australian banks may reduce loan volumes and increase rates to customers. The problems of international banks, especially European banks, previously active in financing local businesses, will compound the problem. These banks are required to increase capital to cover losses, including those on their sovereign bond investment. As they cant or do not want to issue equity at deeply discounted prices and the limited investor appetite for such issues, the banks may sell assets or reduce lending to raise the required capital. Estimates suggest that these banks could have to sell (up to) $2.5-3.0 trillion in assets, resulting in a sharp contraction in availability of credit.

2012 Satyajit Das

Page 4 of 8

australia-southernprovinceofchina(dec2011)

Before the GFC, European banks provided around 35% of loans to Australian corporations. This has fallen to around 16% in 2011 and is likely to decline further as a result of losses on sovereign bond holdings, pressures on bank capital and increases in US$ funding costs. European banks are actively looking to sell all or a portion of their Australian loan portfolios to alleviate the pressures. They are also cutting back on new lending to Australia clients, focusing on their home markets in Europe. Given that Australian companies will need to re-finance around A$80 billion of maturing loans in 2012, these pressures are not welcome. The problems of European banks, active in commodity financing, may reduce the supply of credit to the sector by about 25-30%, which would impact Australias resources businesses. The contraction of credit will also affect Australia indirectly. The withdrawal of European banks from Asia and other emerging markets is affecting the ability of companies to finance trade and investment projects. This affects Australian exports. In 2007, European banks and US banks accounted for 30% and 10% of loan in Asia-Pacific. This has fallen by around half to 15-16% for European banks and 5-6% for US banks. The level of participation is likely to shrink further as a result of the problems of these banks. Troubled French banks account for about 11% of maturing loans in Asia Pacific. It is unlikely that these banks will maintain their level of commitment. Asia-Pacific banks have taken up the slack but are not sizeable enough to fill the gap completely. Australian companies overseas earnings also face significant pressure due to economic weakness in Europe and its affect on the other markets. A proportion of Australian retirement savings is invested overseas. These will also be affected by the problems in Europe and internationally. The European crisis has affected Australian public finances. Falls in income and capital gains have reduced tax revenue. The government is cutting expenditure and tightening taxes to offset the reduction in revenue. Falls in income on retirement savings, reduced business investment and general loss of confidence is likely to adversely affect the domestic economy. Australia may not escape the possible European tsunami. A Fork in the Economic Road The commodity boom has created a two track economy as your Excellency know economists prominent in the media love glib sound bites. The mining and commodity boom benefits a small part of the economy whilst simultaneously creating problems for other parts. The mining and energy sector account for less than 10% of the Australian economy. This is smaller than the Australian finance sector or manufacturing industry. Mining and mining-related sectors, such as construction, manufacturing and services industries which benefit from mining activity, make up about 20% GDP. These sectors will contribute approximately two-thirds of the projected 4% GDP in 2011/12. The remaining 80% of economy will contribute onethird of growth. Mining employs 1.5% of the workforce reflecting its capital intensive nature. Unfortunately, a portion of the equipment needed is imported adding to the current account problem, especially in the short run. A combination of high domestic costs and the strong Australian dollar means that a significant portion of project related work is now done offshore. The revenue earned and the overall contribution to national income does boost the economy and creates employment. But dividends and interest payments to overseas investors reduce the amount of earnings that stays in Australia.

2012 Satyajit Das

Page 5 of 8

australia-southernprovinceofchina(dec2011)

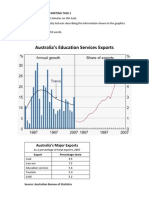

The concentration of mining activity in Western Australia and Queensland also creates imbalances within the domestic economy. Skill shortages in mining means rising salaries, attracting workers from other industries and placing pressure on general wage levels. It also exaggerates property price increases in some areas. This creates inflationary pressure that forces the Reserve Bank of Australia to raise interest rates. The rising demand for Australias mineral exports also pushed up the value of the Australian dollar. Since deregulation in 1983, one Australia dollar has purchased, on average, around 77 US cents. The commodity boom and Australias high interest rates relative to the rest of the world increased the value to around 95 to 100 US cents, peaking at around 110 US cents. The high Australian dollar places exporters at a cost disadvantage and also makes it difficult to compete with cheaper imports. Affected sectors include key Australian export industries that are significant employers such as education services, tourism and manufacturing. Australia may lose up to 170,000 manufacturing jobs over the next 10 years, almost double lost jobs in the past decade. Unhappy Homes The domestic economy remains lack lustre. Consumers are affected by significant debt levels and weak wage growth. Public spending has fallen reflecting pressure to return the budget to surplus. Business investment has been weak, reflecting sluggish demand. Debt levels remain high. Between 1991 and 2011, household debt rose from around 49% to 156% of disposable income. In 1989, when mortgage rates were 17%, the ratio of interest payments to disposable income was 9%. Currently, despite the fact that mortgage rates are around 7.5%, the ratio has increased to around 12%. As households increase savings and reduce debt, consumption is lower contributing to slower growth. Slow growth in credit, reflecting households reducing debt and problem in the banking sector, also constrains growth. Employment in manufacturing, retail and financial services is weakening, with major employers announcing layoffs. There are other unresolved problems. Housing prices remain high based on traditional measures such as affordability and rental returns. According to the latest Economist survey (published on 26 November 2011), Australian house prices were overvalued by 53% based on rents and 38% measured against income levels relative to long run averages. According to The Economist, Australian home prices are overvalued by at least 25% based on the average of these two measures. The level of overvaluation is greater than in America at the peak of its housing bubble. As your Excellency personally experienced during his visit to Australia, no subject excites greater passion among the locals than house prices. This is a staple of conversation and people excitedly compare the size of their mortgages and the value of their accommodation. There is heated disagreement between those who believe that house prices will not fall and other who forecast substantial price falls. The real issue is over investment in housing stock, which produces low or nil return for inhabitants. Encouraged by complex subsidies, large amounts of capital are locked up in housing, unavailable for more productive wealth creating activities such as new industries. In international rankings, Australia regularly performs poorly in competitiveness, productivity and innovation. This is inconsistent with the national character, which prides over achievement in competitive sports. Australia believes it can punch above its weight. In a recent paper entitled Productivity The Lost Decade, economist Saul Eslake found that Australias productivity growth during the 2000s was 0.50% below that of the 1990s, when it was broadly comparable to the OECD average. Between the mid 1990s and the mid 2000s, annual labour productivity declined from 2.8% to 0.9% per annum. Over a similar periods, broader measures of productivity that incorporate capital as well as labour fell from 1.6% to near zero. 2012 Satyajit Das Page 6 of 8

australia-southernprovinceofchina(dec2011)

The GE Global Innovation Barometer ranked Australia 16th out of 30 countries, well behind the leaders like the US and Japan. While 18% of local business leader, perhaps blinded by patriotism, nominated Australia, only 2% of global senior business executives citing the country as an innovation champion. The GFC also significantly reduced the wealth of individuals, especially retirees. The value of their investments declined. At the same time, income and returns from investments also declined. The wealth effect limits consumption but also encourages those planning for retirement to increase their savings. These problems mean that Australias non-mining sector is forecast to grow at a modest 1% per annum, compared to the mining sector which is forecast to grow at 5%. Where are We Now Your excellency, the country is a fest of complacency. Locals are convinced that there is no end in sight for the mining boom driven by Chinas growth. They believe that they are protected against the problems in Europe and elsewhere. Anyone who points out the risks is dismissed as a pessimist and doomsayer. Despite the recovery, many parts of the economy, other than the buoyant mining sector, remain subdued. The stock market, although not an accurate measure of economic health, remains over 30% below its levels before the crisis. Interest rates for 3 and 10 year government bonds have fallen sharply to record lows, reflecting increased pessimism amongst investors about economic prospects. Australia remains vulnerable. A slowdown in Chinese growth and fall in commodity prices and volumes would affect the economy adversely. Australian history suggests that mining booms are finite and end suddenly causing significant disruption. Problems in sovereign debt and attendant pressures on banking system may decrease available funding and increase borrowing costs for Australian banks and companies. Overvalued house prices and high household debt increases vulnerability to an economic slowdown, with an accompanying rise in unemployment or to higher mortgage rates. A credit crunch or recession could cause house prices to fall worsening domestic conditions, which would in turn affect domestic banks. The perfect storm for Australia would be the coincidence of those events. Australia has some flexibility. Public debt around A$250 billion is a modest 22% of GDP providing flexibility to stimulate the economic. But this capacity can be over estimated. Prior to the GFC, Irelands debt levels were modest around 25% of GDP but the need to bailout troubled banks and the collapse of the real estate market led to debt levels increasing rapidly. Australian interest rates are relatively high (official rates are 4.25%), providing flexibility to cut borrowing costs to buffer any shock. The currency is flexible and a fall in value of the Australian dollar would help cushion any weakness, as was the case in 1997/1998 Asian crisis and again in the GFC. Your Excellency will also be aware that Australia Treasurer Wayne Swan was recently anointed as the worlds best Finance Minister. His skills may assist in navigating through any crisis, should such an event occur. But it is worth noting that a previous Australian Treasurer received similar accolades in 1984, only to subsequently preside over a deep recession, which the country had to have. Your Excellency has requested my recommendations for whether we should launch our bid for Australia, to be renamed the Great Southern Province of China. I believe that we should await developments. We should be able to acquire Australia at a cheaper price in the not too distant future. Yours truly The Chinese Envoy

2012 Satyajit Das

Page 7 of 8

australia-southernprovinceofchina(dec2011)

2012 Satyajit Das All Rights Reserved. Satyajit Das is author of Extreme Money: The Masters of the Universe and the Cult of Risk (2011)

2012 Satyajit Das

Page 8 of 8

You might also like

- Too Much Luck: The Mining Boom and Australia’s FutureFrom EverandToo Much Luck: The Mining Boom and Australia’s FutureRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- Topic 2 - Australia's Place in The Global EconomyDocument11 pagesTopic 2 - Australia's Place in The Global EconomyedufocusedglobalNo ratings yet

- Economist Insights 10 December2Document2 pagesEconomist Insights 10 December2buyanalystlondonNo ratings yet

- Citic Draft Final Draft 10 Jan 2014Document14 pagesCitic Draft Final Draft 10 Jan 2014Ashwin ShrivastavaNo ratings yet

- Clase 7 - ActividadesDocument3 pagesClase 7 - ActividadesjuanpablofisicaroNo ratings yet

- Business in Canada ComsatsDocument17 pagesBusiness in Canada Comsatsfarhan harcho100% (1)

- PESTLE Analysis Example of AustraliaDocument12 pagesPESTLE Analysis Example of AustraliaNikita DakiNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Globalisation On The Australian EconomyDocument8 pagesThe Impact of Globalisation On The Australian EconomyEngr AtiqNo ratings yet

- Australia Commodities and Competitiveness - CaseStudyDocument2 pagesAustralia Commodities and Competitiveness - CaseStudyvishnuvrnNo ratings yet

- Deflation: Causes of InflationDocument4 pagesDeflation: Causes of InflationUpasana AroraNo ratings yet

- Weekly OverviewDocument3 pagesWeekly Overviewapi-150779697No ratings yet

- Deloitte - The East Eyes The West CoastDocument22 pagesDeloitte - The East Eyes The West CoastThe Vancouver SunNo ratings yet

- Position PaperDocument2 pagesPosition PaperMus'ab UsmanNo ratings yet

- Finnacial CrisiDocument5 pagesFinnacial Crisikarima salemNo ratings yet

- ASJ #2 May 2012Document60 pagesASJ #2 May 2012Alex SellNo ratings yet

- Terms of Reference: Sr. No Name Roll No. 1 2 3 4 5 6Document9 pagesTerms of Reference: Sr. No Name Roll No. 1 2 3 4 5 6wolverine987No ratings yet

- Australia's Trade and Financial FlowsDocument7 pagesAustralia's Trade and Financial Flowsatiggy05No ratings yet

- Australia To Benefit From China Ties For Some Time Yet: Economic Research NoteDocument2 pagesAustralia To Benefit From China Ties For Some Time Yet: Economic Research Notealan_s1No ratings yet

- Australian Securitisation Journal: TailorDocument60 pagesAustralian Securitisation Journal: TailorAlex SellNo ratings yet

- Margin - The Journal of Applied Economic Research-2010-Vines-157-75Document19 pagesMargin - The Journal of Applied Economic Research-2010-Vines-157-7525526No ratings yet

- Australia's Trade and Balance of PaymentsDocument34 pagesAustralia's Trade and Balance of PaymentsJackson BlackNo ratings yet

- Weekly OverviewDocument4 pagesWeekly Overviewapi-150779697No ratings yet

- Strategy Radar - 2012 - 1012 XX Potential Housing BubbleDocument2 pagesStrategy Radar - 2012 - 1012 XX Potential Housing BubbleStrategicInnovationNo ratings yet

- Sol-0298commerce AnswersDocument18 pagesSol-0298commerce AnswersicewallowhaNo ratings yet

- Gold Ex Plainer September 19 2010Document6 pagesGold Ex Plainer September 19 2010Radu LucaNo ratings yet

- Property Report MelbourneDocument0 pagesProperty Report MelbourneMichael JordanNo ratings yet

- Spring NewsletterDocument8 pagesSpring NewsletterWealthcare Financial SolutionsNo ratings yet

- China and Super: Big Changes Afoot by Robert Gottliebsen.Document4 pagesChina and Super: Big Changes Afoot by Robert Gottliebsen.AKFinancialPlanningNo ratings yet

- Economic Analysis Current Global Economy Scenario - Similar To Market Crash of 1929Document32 pagesEconomic Analysis Current Global Economy Scenario - Similar To Market Crash of 1929Jariwala BhaveshNo ratings yet

- 8-15-11 Steady As She GoesDocument3 pages8-15-11 Steady As She GoesThe Gold SpeculatorNo ratings yet

- Weekly CommentaryDocument4 pagesWeekly Commentaryapi-150779697No ratings yet

- 1-23-12 More QE On The WayDocument3 pages1-23-12 More QE On The WayThe Gold SpeculatorNo ratings yet

- AUSTRALIA - Porters 5 ForcesDocument14 pagesAUSTRALIA - Porters 5 ForcesSai Vasudevan100% (1)

- Australia Towards Globalization 2Document6 pagesAustralia Towards Globalization 2Arjay YsaacNo ratings yet

- Balance of Payments EssayDocument2 pagesBalance of Payments EssayKevin Nguyen100% (1)

- Investing in CommoditiesDocument2 pagesInvesting in CommoditiesAsim QaiserNo ratings yet

- QBAMCO - It's Time PDFDocument6 pagesQBAMCO - It's Time PDFplato363No ratings yet

- Topic: Financial Services - Banking Sector Industry/sector BackgroundDocument4 pagesTopic: Financial Services - Banking Sector Industry/sector Backgroundkanika agrawalNo ratings yet

- Who Owns Australia: Exposing The MultinationalsDocument24 pagesWho Owns Australia: Exposing The MultinationalsCSNo ratings yet

- Effects of A High CAD EssayDocument2 pagesEffects of A High CAD EssayfahoutNo ratings yet

- Economic AnalysisDocument10 pagesEconomic AnalysiswanderwithaishNo ratings yet

- Daily Reckoning Looming Aussie Recession PDFDocument11 pagesDaily Reckoning Looming Aussie Recession PDFMino Zo SydneyNo ratings yet

- ANZ China in FocusDocument31 pagesANZ China in FocusrguyNo ratings yet

- Strategy Radar 2012 0323 XX Mining BoomDocument3 pagesStrategy Radar 2012 0323 XX Mining BoomStrategicInnovationNo ratings yet

- Aus Japan Report FinalDocument32 pagesAus Japan Report FinalMasudRanaNo ratings yet

- Structure: Lewis: Chapter 1 - An Overview of The Australian EconomyDocument7 pagesStructure: Lewis: Chapter 1 - An Overview of The Australian Economydesidoll_92No ratings yet

- Economic Downturns and Business EnvironmentDocument5 pagesEconomic Downturns and Business EnvironmentJohn Michael MagpantayNo ratings yet

- Fin CrisesDocument4 pagesFin CriseshelperforeuNo ratings yet

- NYU Presentation 11 17 10 v3 - 0Document48 pagesNYU Presentation 11 17 10 v3 - 0Kevin CreaseyNo ratings yet

- Outlook 2011: Three Dominant Factors Will Impact Gold, Silver and Platinum in 2011Document16 pagesOutlook 2011: Three Dominant Factors Will Impact Gold, Silver and Platinum in 2011Khalid S. AlyahmadiNo ratings yet

- Economic Insight Report-24 Sept 15Document3 pagesEconomic Insight Report-24 Sept 15Anonymous hPUlIF6No ratings yet

- Presidential CaseDocument9 pagesPresidential CaseVilgia Delarhoza0% (1)

- Demand and Supply of Certain Resources in Australia and Factors Other Than Price Which Affect Demand and SupplyDocument6 pagesDemand and Supply of Certain Resources in Australia and Factors Other Than Price Which Affect Demand and Supplyfatemah zahidNo ratings yet

- AFR - Scott Powers InterviewDocument2 pagesAFR - Scott Powers Interviewkaren_cooper412No ratings yet

- Inside Australia: How Economic Reforms and Structure Affect BOPDocument2 pagesInside Australia: How Economic Reforms and Structure Affect BOPxxsunflowerxxNo ratings yet

- A Period of Consequence - How Abraaj Sees The World & Outlook, Dec 2008Document66 pagesA Period of Consequence - How Abraaj Sees The World & Outlook, Dec 2008Shirjeel NaseemNo ratings yet

- Watchdog April 1992Document68 pagesWatchdog April 1992Lynda BoydNo ratings yet

- 5 Reasons Why Gold Will RiseDocument1 page5 Reasons Why Gold Will RisejogalbhushanNo ratings yet

- Australia's R-Word - Rebalancing Not Recession PDFDocument24 pagesAustralia's R-Word - Rebalancing Not Recession PDFJames WoodsNo ratings yet

- CAD and External StabilityDocument4 pagesCAD and External Stabilityjonno100% (1)

- UntitledDocument2 pagesUntitledapi-90504428No ratings yet

- Media Release: The Hon Christopher Pyne MPDocument2 pagesMedia Release: The Hon Christopher Pyne MPapi-90504428No ratings yet

- For Immediate Release Statement From Jason Akermanis - Thursday 22 March 2012Document1 pageFor Immediate Release Statement From Jason Akermanis - Thursday 22 March 2012api-90504428No ratings yet

- Jimmy Barnes Announcement: Back On Deck in A Few Weeks Time."Document1 pageJimmy Barnes Announcement: Back On Deck in A Few Weeks Time."api-90504428No ratings yet

- CDR Sample For EADocument32 pagesCDR Sample For EARonald Shaikat HalderNo ratings yet

- Ausimm Register Members 102012Document287 pagesAusimm Register Members 102012Randy CavaleraNo ratings yet

- Victorian Rail Industry Operators' Group Standards (VRIOGS)Document1 pageVictorian Rail Industry Operators' Group Standards (VRIOGS)44934640% (1)

- Economy of AustraliaDocument4 pagesEconomy of AustraliaVarun KumarNo ratings yet

- ACAC Report 0810 - SMDocument84 pagesACAC Report 0810 - SMharshil84No ratings yet

- AUSTRALIA - Porters 5 ForcesDocument14 pagesAUSTRALIA - Porters 5 ForcesSai Vasudevan100% (1)

- Faculty of Business Manamgent & Globalization: International Economics Group AssignmentDocument6 pagesFaculty of Business Manamgent & Globalization: International Economics Group AssignmentDibya sahaNo ratings yet

- Jessica Bank StatementDocument8 pagesJessica Bank StatementJohn ReidNo ratings yet

- Week 12 Presentation Case ABC Learning PDFDocument12 pagesWeek 12 Presentation Case ABC Learning PDFNishat NabilaNo ratings yet

- Career FAQs - Accounting PDFDocument150 pagesCareer FAQs - Accounting PDFmaustroNo ratings yet

- 179.N.G.T. Travel Pty LTD ASICDocument1 page179.N.G.T. Travel Pty LTD ASICFlinders TrusteesNo ratings yet

- ON Report - 061114 - FNL PDFDocument84 pagesON Report - 061114 - FNL PDFFredNo ratings yet

- Financial of Apply Principle Task 1 ChangedDocument6 pagesFinancial of Apply Principle Task 1 ChangedHumayun KhanNo ratings yet

- Dy AustraliaDocument2 pagesDy AustraliaANDREA LOUISE ELCANONo ratings yet

- 002.LEVINE A: ASIC Personal Name ExtractDocument42 pages002.LEVINE A: ASIC Personal Name ExtractFlinders TrusteesNo ratings yet

- Week 10 - Tutorial QuestionsDocument7 pagesWeek 10 - Tutorial QuestionsLizNo ratings yet

- IELTS Writing Task 1 Australian Education Exports With Sample EssayDocument2 pagesIELTS Writing Task 1 Australian Education Exports With Sample EssayJohn SalterNo ratings yet

- MWV Web ServicesDocument48 pagesMWV Web ServicesRathna SubbuNo ratings yet

- 1800 AU Public Companies - TRANSFER AGENT - 1800 MarieDocument72 pages1800 AU Public Companies - TRANSFER AGENT - 1800 MarieMarie Santos - Raymundo100% (1)

- TransactionSummary NovDocument6 pagesTransactionSummary NovCarlos SanabriaNo ratings yet

- Country Link NetworkDocument1 pageCountry Link NetworkAmit JoshiNo ratings yet

- Scoping Report - The Future Movement GroupDocument24 pagesScoping Report - The Future Movement Groupapi-524390944100% (1)

- Wiiklic Pty LTDDocument1 pageWiiklic Pty LTDapi-278870838No ratings yet

- CAD EssayDocument4 pagesCAD Essayshelterman14No ratings yet

- Statements 20230714Document6 pagesStatements 20230714Sima KadirNo ratings yet

- Foreign Investment and Australian AgricultureDocument60 pagesForeign Investment and Australian AgricultureABC News OnlineNo ratings yet

- VOIP New Call Rates PDFDocument285 pagesVOIP New Call Rates PDFMalvin RitoNo ratings yet

- 12-Month NBN Rollout PlanDocument2 pages12-Month NBN Rollout PlanJames HutchinsonNo ratings yet

- Ws Num LCM HCF 01QA PWDocument2 pagesWs Num LCM HCF 01QA PWdeyaa1000000No ratings yet

- EQ Holdings 09Document48 pagesEQ Holdings 09Frode HaukenesNo ratings yet