Professional Documents

Culture Documents

EDUC 201 (Chapter II) Part 1

Uploaded by

Jeffrey GalvezOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

EDUC 201 (Chapter II) Part 1

Uploaded by

Jeffrey GalvezCopyright:

Available Formats

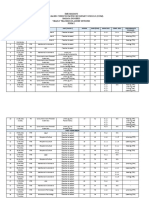

Page 1 of 4 EDUC 201 History and Philosophical Foundation of Education II.

HISTORICAL FOUNDATION OF EDUCATION (Part 1) *Education in Preliterate Societies Before the invention of reading and writing, people lived in an environment in which they struggled to survive against natural forces, animals, and other humans. To survive, preliterate people developed skills that grew into cultural and educational patterns. For a particular groups culture to continue into the future, people had to transmit it, or pass it on, from adults to children. The earliest educational processes involved sharing information about gathering food and providing shelter; making weapons and other tools; learning language; and the values, behaviour, and religious rites or practices of a given culture. Through direct, informal education, parents, elders, and priests taught children the skills and roles they would need as adults. These lessons eventually formed the moral codes that governed behaviour. Since they lived before the invention of writing, preliterate people used an oral tradition, or storytelling, to pass on their culture and history from one generation to the next. By using language, people learned to create and use symbols, words, or signs to express their ideas. When these symbols grew into pictographs and letters, human beings created a written language and made the great cultural leap to literacy. *Education Ancient Chinese Civilization Confucius, the great educator, devoted all his life to the private school system and instructed most students. It is said that over three thousand disciples followed him, among whom there were 72 sages who went on to broaden the acceptance of the philosophy set out by their master Confucianism: a philosophy embracing benevolence in living, diligence in learning, and so on. Other schools, such as Taoism, also taught widely and this led afterwards to 'a hundred schools of thought' in the Warring States Period. During the succeeding years, private schools continued to exist although there were times when state education became fashionable. In 136 BC during the reign of Emperor Wudi (156 BC - 87 BC), the government introduced a system which was named 'taixue'. Usually the students were provided with a free diet and mainly studied the classical Confucian books. Following examinations, jdgalvez those with good marks would directly be given official titles. In the Han Dynasty there had been no system for testing a person's ability, and the most prevalent method was merely through observation. Officials would see who was intelligent and recommend individuals to their superior. This obviously restricted the source of talented people and did little to provide any kind of equality for the population as a whole. Such a system could only lead to nepotism and corruption and the need for a different means of selection had to be sought. *Education in Indian Civilization An early civilization that flourished along the banks of the IndusGanges River was Hindu civilization. The Hindus were categorized by birth into different social classes (caste system): Brahmins the priestly class Kshatrias the class of warriors or military executives Vaishyas the industrial class Shudras the service class Pariahs the outcasts or untouchables who were tasked with collecting garbage, burying corpse, and other menial jobs. Education for the Hindus was of philosophical and religious nature. The Hindus believed in reincarnation or continuous rebirth. Education is based in religious texts Vedas, Bhagavad Gita, and the Upanishads. Types of Schools: 1. Brahminic School for the priestly caste stressing the Vedas, religion, and philosophy 2. Tols or one-room school where a single teacher taught religion and law 3. Court schools sponsored by princes 4. Temple schools emphasized religion and rituals Indias educational system provided no social mobility schooling was reserved for the Brahmins. *Education in Greek Civilization The Greeks made the greatest educational advances of ancient times. In fact, Western education today is based on the ancient Greek model. Greek civilization flourished from about 700 B.C. to about 330 B.C. During this period, Greek arts, philosophy, and science became the foundations of Western thought and culture. Homer and other Greek writers created new forms of expression, including lyric and epic poetry. The greatest Greek poet was Homer. Homer composed two famous poems, the Iliad and the Odyssey, during the 700's B.C.

Page 2 of 4 Ancient Greece was divided into city-states, independent states that consisted of a city and the region surrounding it. The educational system of each city-state aimed to produce good citizens. Athens and Sparta, two of the most powerful city-states, had different ideals of citizenship. In Sparta, citizens were also expected to develop their bodies and serve the state. Sparta, the chief political enemy of Athens, was a dictatorship that used education for military training and drill. In contrast to Athens, Spartan girls received more schooling but it was almost exclusively athletic training to prepare them to be healthy mothers of future Spartan soldiers. Athens made the greatest educational advances of any Greek city-state. But Athenian education was far from democratic. Education was limited to the sons of Athenian citizens. Less than half of all Athenians were citizens. Slaves made up a large part of the Athenian population and were not considered worthy of an education. Athenian boys started their education at about age 6. But they did not go to schools as we think of schools today. A trusted family slave simply took them from teacher to teacher, each of whom specialized in a certain subject or certain related subjects. Boys studied reading, writing, arithmetic, music, dancing, and gymnastics. As the boys advanced, they memorized the works of Homer and other Greek poets. Boys continued their elementary education until they were about 15 years old. From about ages 16 to 20, they attended a government-sponsored gymnasium. Gymnasiums trained young men to become citizen-soldiers. They emphasized such sports as running and wrestling and taught civic duty and the art of war. Students held discussions in order to improve their reasoning and speaking ability. In the 400s BC, the Sophists, a group of wandering teachers, began to teach in Athens. The Sophists claimed that they could teach any subject or skill to anyone who wished to learn it. They specialized in teaching grammar, logic, and rhetoric, subjects that eventually formed the core of the liberal arts. The Sophists were more interested in preparing their students to argue persuasively and win arguments than in teaching principles of truth and morality. Unlike the Sophists, the Greek philosopher Socrates sought to discover and teach universal principles of jdgalvez truth, beauty, and goodness. Socrates, who died in 399 BC, claimed that true knowledge existed within everyone and needed to be brought to consciousness. His educational method, called the Socratic Method, consisted of asking probing questions that forced his students to think deeply about the meaning of life, truth, and justice. Plato, who had studied under Socrates, established a school in Athens called the Academy. Plato believed in an unchanging world of perfect ideas or universal concepts. He asserted that since true knowledge is the same in every place at every time, education, like truth, should be unchanging. Plato described his educational ideal in the Republic, one of the most notable works of Western philosophy. Platos Republic describes a model society, or republic, ruled by highly intelligent philosopher-kings. Warriors make up the republics second class of people. The lowest class, the workers, provides food and the other products for all the people of the republic. In Platos ideal educational system, each class would receive a different kind of instruction to prepare for their various roles in society. Platos student, Aristotle, founded his own school in Athens called the Lyceum. Believing that human beings are essentially rational, Aristotle thought people could discover natural laws that governed the universe and then follow these laws in their lives. He also concluded that educated people who used reason to make decisions would lead a life of moderation in which they avoided dangerous extremes. Greek orator Isocrates developed a method of education designed to prepare students to be competent orators who could serve as government officials. Isocratess students studied rhetoric, politics, ethics, and history. They examined model orations and practiced public speaking. Isocratess methods of education directly influenced such Roman educational theorists as Cicero and Quintilian. *Education in Roman Civilization While the Greeks were developing their civilization in the areas surrounding the eastern Mediterranean Sea, the Romans were gaining control of the Italian peninsula and areas of the western Mediterranean. The Greek education focused on the study of philosophy. The Romans, on the other hand, were preoccupied with war, conquest, politics, and civil

Page 3 of 4 administration. As in Greece, only a minority of Romans attended school. Schooling was for those who had the money to pay tuition and the time to attend classes. While girls from wealthy families occasionally learned to read and write at home, attended primary school called ludus. In secondary schools they studied Latin and Greek grammar taught by Greek slaves, called pedagogues. In primary and secondary school, wealthy young men attended schools of rhetoric or oratory that prepared them to be leaders in government and administration. Cicero, a Roman senator, combined Greek and Roman ideas on how to educate orators in his book De Oratore. Like Isocrates, Cicero believed orators should be educated in liberal arts subjects such as grammar, rhetoric, logic, mathematics, and astronomy. He also asserted that they should study ethics, military science, natural science, geography, history, and law. Quintilian, an influential Roman educator, wrote that education should be based on the stages of individual development from childhood to adulthood. Quintilian devised specific lessons for each stage. He also advised teachers to make their lessons suited to the students readiness and ability to learn new material. He urged teachers to motivate students by making learning interesting and attractive. *Arabic Learning and Education The Prophet Muhammad said "it is the duty of every Muslim man and woman to seek education," and under his influence, the Arabs were encouraged to pursue knowledge for its own sake. Fulfilling the duty to pursue knowledge gave Muslims a headstart in education. Among the early elementary educational institutions were the mosque schools which were founded by the Prophet himself; he sat in the mosque surrounded by a halqa (circle) of listeners, intent on his instructions. Muhammad also sent teachers to the various tribes to instruct their members in the Qur'an. The formal pursuit of knowledge had existed in one form or another since the time of the Greeks. The Arabs translated and preserved not only the teachings of the Greeks but those of the Indians and the Persians as well. More importantly, they used these basic teachings as a starting point from which to launch a mass revolution in education beginning during the Abbasid dynasty. jdgalvez In the mosque school, the teacher sat on a cushion and leaned against a column or wall as his students sat around him listening and taking notes. Only Muslims were allowed to attend the Qur'an or hadith sessions, but non-Muslims could attend all other subjects. There was no age limit, nor were there any restrictions on women attending classes. Historians such as Ibn Khallikan reported that women also taught classes in which men took lessons. Few Westerners recognize the extent to which Arab women contributed to the social, economic and political life of the empire. Arab women excelled in medicine, mysticism, poetry, teaching, and oratory and even took active roles in military conflicts. Current misconceptions are based on false stereotypes of Arab life and culture popularized by some journalists and "Orientalists." In the mosque schools, rich and poor alike attended classes freely. Classes were held at specific times and announced in advance by the teacher. Students could attend several classes a day, sometimes travelling from one mosque to another. Teachers were respected by their students and there were formal, if unwritten, rules of behaviour. Laughing, talking, joking or disrespectful behaviour of any kind were not permitted. Different teachers used various methods of instruction. Some preferred to teach from a text first and then to answer questions. Others allowed student assistants to read or elaborate upon the instructor's theories while the teachers themselves remained available to comment or answer questions. Still others taught without the benefit of texts. Nizam al-Mulk, a Seljuk vizier, founded the Nizamiyya Madrasa in Baghdad which became the forerunner of secondary/college level education in the Arab empire. Madrasas had existed long before Nizam alMulk, but his contribution was the popularization of this type of school. The madrasa gave rise to various universities in the Arab empire and become the prototype of several early European universities. Founded in 969 A.D., Al-Azhar University in Cairo preceded other universities in Europe by two centuries. Today it attracts students from all over the world. The madrasas, which literally mean "places for learning," were the beginning of departmentalized schools where education was available to all. The madrasas even provided student dormitories.

Page 4 of 4 Each madrasa, depending on its location, had a specific curriculum. The subjects taught were the religious sciences (e.g., the study of the Qur'an, hadith, jurisprudence and grammar) and the intellectual sciences (e.g., mathematics, astronomy, music and physics). As these schools began to attract distinguished teachers and specialists from all corners of the Arab empire, the number of disciplines increased. Teachers received substantial salaries and scholarships and pensions were available for students. Funds for operation of the madrasas came from both the government and private contributions. Since the government placed an important role in promoting these institutions, the subject matter, choice of teachers and allocation of funds were closely supervised and regulated. The development of the madrasa evolved from the various elementary and secondary schools which were prevalent in the Abbasid empire: the mosque schools and other traditional institutions; maktabat, or libraries, which originated in the pre--Islamic Arab world; tutoring houses, palace schools; halqa, discussion groups in the homes of Muslim scholars; and the library salons in the palaces of wealthy men and courtiers who were patrons of learning and scholarship. In addition, there were the majalis or meetings which were presided over by learned men at various social institutions and private homes. The majalis covered a wide range of topics and subjects. In the current revivals of traditional Islam, many of these "old" institutions and customs are being resuscitated. Travelling to other cities to seek knowledge under the direction of different masters was a common practice in the early centuries of Islam. From Kurasan to Egypt, to West Africa and Spain, and from the northern provinces to those in the south, students and teachers journeyed to attend classes and discuss social, political, religious, philosophical and scientific matters. The custom was later popularized in Europe during the Renaissance. Academies began to emerge in the eighth century, serving as centers for the translation of earlier works and for innovative research. Each academy provided rooms for classes, meetings and readings. The Bayt al-Hikma for the Caliph al-Ma'mum (813833 A.D.) and the Dar al-'Ilm of Cairo founded by alHakim (966-1021 A.D.) are the most notable. Books were collected from all over the world to create jdgalvez monumental libraries that housed volumes on medicine, philosophy, mathematics, science, alchemy, logic, astronomy and many other subjects. Along with the introduction of paper and textbooks in the eighth century came the antecedent of "teacher certification." An instructor would give his permission (ijazah) to competent students to teach from one or all of his textbooks. Because of this practice, an individual could have an ijazah to teach a subject although he might be a student in another class. Consequently, the distinction between teacher and student was often minimized. In the eleventh and twelfth centuries, as Arab influence spread to Spain, Sicily and the rest of Europe, Europeans became increasingly aware of Arab advancements in many fields, especially education and science. Books were translated from Arabic into Latin and, later, to vernacular language. European schools which had long limited learning to the "seven liberal arts" began to expand their curricula. For some five hundred years, Arab learning and scholarship played a major role in the development of education in the West. The Arabs brought with them well-developed techniques in translation and research and opened new vistas in areas of medicine, the physical sciences and mathematics. Applications of empiricism in all fields of study were rapidly incorporated into the learning system of those who became familiar with Arab methodology. Long before the popularization of the phrase "transfer of technology," a term used to describe advanced expertise which developed nations offer to Third World countries, the Arabs shared their accumulated knowledge and institutions with the rest of the world.

You might also like

- 2006CON Digital Photos HitchcockDocument51 pages2006CON Digital Photos HitchcockJeffrey GalvezNo ratings yet

- PCS Alma Mater HymnDocument2 pagesPCS Alma Mater HymnJeffrey GalvezNo ratings yet

- Providential Fires Are Caused by Act of God, Like LightningDocument3 pagesProvidential Fires Are Caused by Act of God, Like LightningJeffrey GalvezNo ratings yet

- ValuesDocument14 pagesValuesJeffrey GalvezNo ratings yet

- The Philosophical Foundation of EducationDocument4 pagesThe Philosophical Foundation of EducationJeffrey GalvezNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Unit 1: Speaking About Myself: SBT ModuleDocument3 pagesUnit 1: Speaking About Myself: SBT ModuleYu ErinNo ratings yet

- Bamboo Paper Making: Ages: Total TimeDocument4 pagesBamboo Paper Making: Ages: Total TimeBramasta Come BackNo ratings yet

- Cooperative StrategiesDocument20 pagesCooperative Strategiesjamie.pantoja100% (1)

- CCIP BrochureDocument6 pagesCCIP BrochureHarleen KaurNo ratings yet

- Narrative Report - Curriculum EssetialsDocument10 pagesNarrative Report - Curriculum EssetialsCohen GatdulaNo ratings yet

- Barcelona Objectives - Childcare Facilities For Young Children in EuropeDocument48 pagesBarcelona Objectives - Childcare Facilities For Young Children in EuropeAntonio PortelaNo ratings yet

- EAP 2 - IMRD Research Report and Final IMRD Exam - Rubric - V1Document2 pagesEAP 2 - IMRD Research Report and Final IMRD Exam - Rubric - V1ChunMan SitNo ratings yet

- Master of Science in Biochemistry: A Two-Year Full Time Programme (Rules, Regulations and Course Contents)Document40 pagesMaster of Science in Biochemistry: A Two-Year Full Time Programme (Rules, Regulations and Course Contents)Avinash GuptaNo ratings yet

- DisciplineDocument2 pagesDisciplinedbrown1288No ratings yet

- The Problem and Its BackgroundDocument39 pagesThe Problem and Its BackgroundsigfridmonteNo ratings yet

- Perceived Effects of Lack of Textbooks To Grade 12Document10 pagesPerceived Effects of Lack of Textbooks To Grade 12Jessabel Rosas BersabaNo ratings yet

- Training Process - LDC - 2020Document3 pagesTraining Process - LDC - 2020mircea61No ratings yet

- Silvius RussianstatevisionsofworldorderandthelimitsDocument352 pagesSilvius RussianstatevisionsofworldorderandthelimitsElena AuslevicNo ratings yet

- Evaluating Online SourcesDocument6 pagesEvaluating Online Sourcesapi-216006060No ratings yet

- Lesson Plan F3 Lesson 17 (9 - 5)Document6 pagesLesson Plan F3 Lesson 17 (9 - 5)aisyah atiqahNo ratings yet

- The Telephone COT 3 Lesson PlanDocument3 pagesThe Telephone COT 3 Lesson PlanrizaNo ratings yet

- National Level Science Fair For Young Children 2018.6 SJKT Mukim PundutDocument5 pagesNational Level Science Fair For Young Children 2018.6 SJKT Mukim PundutsjktmplNo ratings yet

- Kindergarten EllDocument78 pagesKindergarten Elllcpender0% (1)

- June 2010 Exam ReportDocument62 pagesJune 2010 Exam ReportCreme FraicheNo ratings yet

- 2013 12 Dec PaybillDocument121 pages2013 12 Dec Paybillapi-276412679No ratings yet

- University of Zambia: Physics Handbook 2009Document62 pagesUniversity of Zambia: Physics Handbook 2009Robin Red MsiskaNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Medical Technology: What Is The Role of Medical Technologist?Document19 pagesIntroduction To Medical Technology: What Is The Role of Medical Technologist?Angeline DogilloNo ratings yet

- Care Coordinator Disease Management Education in Reno NV Resume Silvia DevescoviDocument2 pagesCare Coordinator Disease Management Education in Reno NV Resume Silvia DevescoviSilviaDevescoviNo ratings yet

- Adolphe FerriereDocument22 pagesAdolphe FerriereJulieth Rodríguez RodríguezNo ratings yet

- Conference Green Cities PDFDocument458 pagesConference Green Cities PDFMariam Kamila Narvaez RiveraNo ratings yet

- Study Guide (ITIL 4 Foundation) .PDF Versión 1 (27-44)Document18 pagesStudy Guide (ITIL 4 Foundation) .PDF Versión 1 (27-44)Brayhan Huaman BerruNo ratings yet

- Penjajaran RPT Form 2 With PBDDocument6 pagesPenjajaran RPT Form 2 With PBDSEBASTIAN BACHNo ratings yet

- KiDS COR Policies and Procedures 2009-2010Document3 pagesKiDS COR Policies and Procedures 2009-2010Nick RansomNo ratings yet

- Dr. Xavier Chelladurai: Udemy Online Video Based Courses byDocument1 pageDr. Xavier Chelladurai: Udemy Online Video Based Courses byRonil RajuNo ratings yet

- IIT BHU's E-Summit'22 BrochureDocument24 pagesIIT BHU's E-Summit'22 BrochurePiyush Maheshwari100% (2)