Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Rem CH 1

Uploaded by

Anuj HarveyOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Rem CH 1

Uploaded by

Anuj HarveyCopyright:

Available Formats

UNDERSTANDING REMEDIES

James M. Fischer

Southwestern University School of Law

LEGAL TEXT SERIES

QUESTIONS ABOUT THIS PUBLICATION?

For questions about the Editorial Content appearing in these volumes or reprint permission, please call: Michael Bruno, J.D., at ....................................................... 1-800-252-9257 Ext. 2518 Lon E. Dobbs, J.D., at ........................................................ 1-800-252-9257 Ext. 2315 Outside the United States and Canada please call ................................. (212) 448-2000 For assistance with replacement pages, shipments, billing or other customer service matters, please call: Customer Services Department at ............................................................ (800) 833-9844 Outside the United States and Canada, please call ............................ (518) 487-3000 Fax number ................................................................................................ (518) 487-3584 For information on other Matthew Bender publications, please call Your account manager or ......................................................................... (800) 223-1940 Outside the United States and Canada, please call ................................ (518) 487-3000 Copyright 1999 By Matthew Bender & Company Incorporated

No Copyright is claimed in the text of regulations, statutes, and excerpts from court cases quoted within. All Rights Reserved. Printed in United States of America. 1999 Reprint

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Fischer, James M., 1947Understanding remedies / James M. Fischer. p. cm. (Legal text series) Includes index. ISBN 082052879X 1. Remedies (Law)United States. 2. DamagesUnited States. I. Title. II. Series. KF9010.F57 1999 347.7377dc21

9921683 CIP

Permission to copy material exceeding fair use,17 U.S.C. 107, may be licensed for a fee of 25 per page per copy from the Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA. 01923, telephone (508) 750-8400.

MATTHEW BENDER & CO., INC. EDITORIAL OFFICES 2 Park Avenue, New York, NY 10016-5675 (212) 448-2000 201 Mission St., San Francisco, CA 94105-1831 (415) 908-3200

(Matthew Bender & Co., Inc.) (Pub.586)

Chapter 1, Understanding Remedies, is reproduced from Understanding Remedies by James M. Fischer, Southwestern University School of Law. Copyright 1999 Matthew Bender & Company Incorporated. All rights reserved. A user is hereby granted the right to view, print or download any portion of this sample chapter, so long as it is for the User's sole use. No part of this sample chapter may be sold or distributed by the User to any person in any form, through any medium or by any means.

CHAPTER 1

UNDERSTANDING REMEDIES

SYNOPSIS

1 2 BASIC REMEDIAL GOALS TYPES OF REMEDIES [a] Legal v. Equitable Remedies [b] Specific v. Substitutional Remedies [c] Damages [d] Injunctions [e] Restitution [f] Declaratory Relief [g] Punitive Damages [h] Nominal Damages [i] Presumed Damages RELATIONSHIP WITH SUBSTANTIVE LAW PUBLIC POLICY

3 4

BASIC REMEDIAL GOALS

It is frequently stated that for every wrong there is a remedy. 1 The concept is at the very core of American constitutional government. 2 The concept was recognized by

1 Faria v. San Jacinto Unified Sch. Dist., 50 Cal. App. 4th 1939, 59 Cal. Rptr. 2d 72, 77 (1996); Sanzone v. Board of Police Commrs, 219 Conn. 179, 592 A.2d 912, 921 (1991); Burns v. Burns, 518 So. 2d 1205, 1208 (Miss. 1988). 2 Marbury v. Madison, 5 U.S. 137, 163, 2 L. Ed. 60 (1803) (The government of the United States has been emphatically termed a government of laws, and not of men. It will certainly cease to deserve this high appellation, if the laws furnish no remedy for the violation of a vested legal right). (Matthew Bender & Co., Inc.)

(Pub.586)

UNDERSTANDING REMEDIES

Blackstone, who noted in his commentaries: It is a general and indisputable rule, that where there is a legal right, there is also a legal remedy by suit or action at law whenever that right is invaded. 3 The linking of a remedy for the invasion of rights brings forth several important legal consequences. First, we should note the emotive value of the statement. A wrong will be rectified in fact, not just in principle. Yet, what does it mean to say that a wrong will be rectified? The essential elements of rectification are to undo the injurious effects of the wrong. It must be kept in mind, however, that it is not the injury that gives rise to the remedy, but the legal wrong. 4 An injury accomplished without the infliction of a legal wrong does not give rise to a right to remediation. Some injuries are tolerated, such as the harm a lawyer may inflict on a non-client when the lawyer is acting within the adversarial system. 5 Other harms are encouraged and promoted, such as the economic harm that is the inevitable consequence of competition. 6 Some harms are seen as beyond the ability of courts to redress, usually for reasons of deference and discretion. 7 The coupling of the concepts of wrong and remedy helps demonstrate the essential purpose of remedies, which is to redress the wrong by creating the situation that would have existed had the wrong not occurred. This is often referred to as returning or restoring the plaintiff to the position he would have occupied had the wrong not occurred. 8 This,

1 William Blackstone, Commentaries on the Laws of England 23. Lowery v. Mountain Top Indoor Flea Mkt., Inc., 699 So. 2d 158, 161 (Ala. 1997) (noting that the law doesnt say for every injury there is a remedy. It says for every wrong there is a remedy) [citation omitted]. 5 See, e.g., Levin, Middlebrook, et. al. v. United States Fire Ins. Co., 639 So. 2d 606, 608 (Fla. 1994) (noting that attorneys immunity for defamation in connection with litigation represents necessary accommodation to needs of adversary system); Stern v. Thompson & Coates Ltd., 185 Wis. 2d 220, 517 N.W.2d 658, 666 (1994) (noting attorneys qualified immunity from suits by non-clients for professional advice given client even though advice results in harm to non-clients). 6 Brunswick Corp. v. Pueblo Bowl-O-Mat, 429 U.S. 477, 488, 97 S. Ct. 690, 50 L. Ed. 2d 701 (1977) (holding that federal antitrust policies are not advanced by providing compensation for losses due to increased competition). 7 See, e.g., San Francisco v. United Assn of Journeymen and Apprentices, of the Plumbing and Pipefitting Indus. of U.S. and Canada, Local 38, 42 Cal. 3d 810, 230 Cal. Rptr. 856, 726 P.2d 538, 541 (1986) (holding that absent legislative authorization, the maintenance of an illegal strike by public employees was not redressable in damages by private employers injured by strike) See also Anderson v. St. Francis-St. George Hosp., Inc., 77 Ohio St. 3d 82, 671 N.E.2d 225, 228-29 (1996) (holding that no cause of action existed for wrongfully prolonging the life of a patient in disregard of prior instructions). The court noted: There are some mistakes, indeed even breaches of duty or technical assaults, that people make in this life that affect the lives of others for which there simply should be no monetary compensation. 671 N.E.2d at 228 (citation omitted). 8 Albermarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405, 413-25, 95 S. Ct. 2362, 45 L. Ed. 2d 280 (1975) (purpose of Title VII remedies for unlawful discrimination is to make plaintiff whole and restore him to the position he would have occupied if the wrong had not occurred). See also Milliken v. Bradley, 433 U.S. 267, 280, 97 S. Ct. 2749, 53 L. Ed. 2d 745 (1977) (desegregation decree must be designed to restore victims to position they would have occupied in the absence of wrongful

4 (Matthew Bender & Co., Inc.) (Pub.586) 3

INTRODUCTION TO REMEDIES

however, must be understood to be a process of creation. Unlike the traveler in the familiar Robert Frost poem who could save the road not taken for another day, 9 a party must demonstrate to the satisfaction of the court where that unbeaten path led and that but for the wrong he would have taken it. 10 Placement of the plaintiff in the position he would have occupied but for the wrong is, by necessity, an inexact science given the vagaries of proof and the imprecision of forecasting. Any construction of plaintiffs rightful position is also compromised by competing interests and values that claim a place at the decisional table. These interests and values influence the extent to which the legal system may return or restore the plaintiff to the position he would have occupied but for the wrong. 11 It is these competing interests and values that ultimately dictate the rules, principles, and standards that constitute the law of remedies. 2 TYPES OF REMEDIES

Remedies are flexible. They have been developed both to complement substantive law and to meet the needs of litigants. Because the scope of substantive law is broad and the needs of litigants are diverse, remedies law provides a broad and diverse array of approaches which may be used for the particular situation. Terminology in this area has a rich, historical tradition. In some cases, that tradition has continuing vitality. Moreover, knowing the accompanying remedial types promotes understanding and good practice. In other contexts, the tradition does not have the same claim for continued allegiance. Use of remedial types in this setting can prove counterproductive. The distinctions suggested by the remedial type may no longer be valid or the distinction may be artificial, thus creating confusion. This conflict should be kept in mind when reading the remedial types discussed in this section.

conduct); Lopp v. Peerless Serum Co., 382 S.W.2d 620, 626 (Mo. 1964) (purpose of restitution is restoration of injured party to as good a position as was occupied by him prior to the commission of the wrong). 9 Robert Frost, The Road Not Taken in Complete Poems of Robert Frost 131 (1964). 10 Ward v. Papas Pizza To Go, Inc., 907 F. Supp. 1535, 1544 (S.D. Ga. 1995) (Plaintiffs rightful place appears to be roughly the position she now holds and the wage she now earns . . . [i]f it is not, no one can safely formulate the appropriate alternative); see also Munn v. Algee, 924 F.2d 568, 575 (5th Cir. 1991) (refusing to compensate plaintiff for the hypothetical injuries she would have sustained had she acted properly to mitigate damages when, on the facts, she failed to mitigate damages), cert. denied, 502 U.S. 900 (1991); Meletio Sea Food Co. v. Gordons Transps., 191 S.W.2d 983, 985 (Mo. Ct. App. 1946) (stating that basic principles of law of damages . . . contemplates that the remedy provided in a given case shall only afford compensation for whatever injury is actually sustained) (citations omitted). 11 Kraemer v. Franklyn & Marshall College, 941 F. Supp. 479, 483 (E.D. Pa. 1996) (instatement (sic) is not an appropriate remedy if it requires bumping or displacing an innocent employee in favor of the plaintiff who would have held the [position but for the wrong]) (citation omitted); but see Lander v. Lujan, 888 F.2d 153, 156 (D.C. Cir. 1989) (adopting bumping theory when necessary to place plaintiff in rightful position).

(Matthew Bender & Co., Inc.) (Pub.586)

UNDERSTANDING REMEDIES [a] Legal v. Equitable Remedies

2[a]

The distinction between legal and equitable remedies is basic to the law of remedies, even as its importance is diminishing due to the merger of the two systems in most jurisdictions. The distinction between law and equity serves as the beginning for the distinction between legal and equitable remedies. Put simply, legal remedies are those available in the law courts and equitable remedies are those available in equity courts. As will be abundantly clear throughout this book, nothing could be so easy, and easy it is not. For in fact remedies at law were often available in equity, under the equity clean-up rule, and many equity principles were adopted by the law courts. The reasons for this migration of rules and doctrine between supposedly independent systems is addressed elsewhere. 1 The point here is that the current legal system reflects a hodgepodge of rules that both imitate past practice and reflect differences with the past. The importance of the law-equity distinction today lies in the fact that some remedies are only available on one side of the distinction but not the other. The merger of law and equity notwithstanding, accessing legal rather than equitable remedies can generate procedural differences, primarily with regard to jury trial. The distinction between legal and equitable remedies remains important notwithstanding the formal merger of the two systems. [b] Specific v. Substitutional Remedies A specific remedy is one that gives the plaintiff exactly what she would have if the legal wrong had not been committed. An example of this is specific performance. The remedy gives the plaintiff exactly what she bargained for and is legally entitled to receive defendants performance under the contract. A substitutional remedy is just what the term suggestssomething other than a specific remedy. Returning to the contract example, a substitutional remedy for breach would give the plaintiff the dollar value of defendants performance, as opposed to the actual performance itself. There is a tendency to attribute specific remedies to equity and substitutional remedies to law. As with any generalization there is a basis for the attribution, but it is entirely descriptive, not normative. The descriptive is accurate, but it is not complete. The nature of equitable remedies, particularly injunctive relief, is that they tend to favor specific remedies. Specific remedies claims appear to dominate because, as a practical matter, a frequent invocation of equity is for injunctive relief. In fact, substitutional remedies are frequently sought in equity, as for example, damages for breach of fiduciary duty. The flip side of the issue is that while substitutional remedies appear to dominate at law, specific remedies are also frequently invoked. For example, the common law legal remedies of ejectment and replevin were specific remedies for the recovery of real and personal property, respectively. Modernly, both remedies are available, sometimes under different names.

1

Section 20 (The Historical Relationship Between Law and Equity).

(Pub.586)

(Matthew Bender & Co., Inc.)

2[d]

INTRODUCTION TO REMEDIES

The distinction between specific and substitutional remedies is helpful in the sense that it focuses awareness on exactly what one is seeking, but aside from the context of prioritizing remedies, 2 the distinction has little importance. Moreover, money is often sought as a specific remedy, for example, as reimbursement under principles of indemnity for discharging anothers obligation. Characterization of the remedy in this case as specific or substitutional does little more than aid confusion. [c] Damages

Damages is a term used today to identify the recovery of monetary compensation for loss caused by the legal wrong of another. Thus, we commonly speak of breach of contract damages or personal injury damages. In both of these cases, the idea of damages refers to the losses caused by the defendants breach of the contract or the defendants breach of duty. The common practice is to award a sum of money to compensate the plaintiff for the damages sustained. This obviously requires that the damages themselves be determined in the form of a monetary loss to the plaintiff. In other words, the loss due to a defendants non-performance of a contractual obligation must be determined as a monetary loss, i.e., what was performance worth and what was lost by non-performance. Similarly, in a personal injury case, we must calculate the loss in dollars, although in this context we do so because a bodily injury claim can only be remedied through substitutional forms. Damages may be compensatory or punitive, general or special, or economic or noneconomic. The common denomination for each form of damages is, however, that the award be in money for the loss or detriment caused by the defendant. 3 The idea is to place the plaintiff in the position she would have occupied but for the legal wrong by using money to ameliorate the consequences of that legal wrong to the plaintiff. [d] Injunctions Injunctions are a form of equitable relief whereby a defendant is ordered to do something (mandatory injunction) or refrain from doing something (prohibitory or negative injunction). A defendant who violates the terms of an injunction may be sanctioned by being held in contempt of court. The idea is to coerce compliance with legal obligations. The injunction may prevent a plaintiffs legitimate legal position from being altered by a defendant (preventative injunction). Alternatively, the injunction may restore or return the plaintiff to the position he would have occupied but for defendants wrongful conduct by undoing the continuing effects of that wrongful conduct (reparative injunction).

Section 21 (Adequacy of Remedy at Law/Irreparable Injury). The definition of damages can be exceedingly important when the defendants liability insurance covers loss caused by damages. A broad reading of the insurance contract may lead to claims being covered that would not fall within a remedies definition of damages. AIU Ins. Co. v. Superior Court, 51 Cal. 3d 807, 274 Cal. Rptr. 820, 799 P.2d 1253, 1266 (1990) (insurance policy obligating carriers to pay included, under the circumstances, injunctive relief and the recovery of clean-up responses costs under CERCLA).

3 (Matthew Bender & Co., Inc.) (Pub.586) 2

6 [e]

UNDERSTANDING REMEDIES Restitution

2[e]

Restitutionary remedies are designed to force the defendant to disgorge a benefit when retention of that benefit would constitute unjust enrichment. The basic principle here is that defendant is holding something that in fairness and justice should be held instead by the plaintiff. The plaintiffs claim may be inferior to that of a third party, but it is always superior to that of the defendant. While restitutionary remedies are guided by equitable principles of fairness and justice, the remedies themselves may be available in law ( e.g., quasi contract) or in equity ( e.g., subrogation). The location of the restitutionary remedy in law or equity is important when procedural issues are raised, as for example, the right to a jury trial in an action for rescission, or when additional equitable remedies, such as a constructive trust or equitable lien, are sought. [f] Declaratory Relief Declaratory relief provides a judicial statement of the parties rightful legal position with respect to a particular matter. The most common example of this remedy is the declaratory judgment, but other remedies fall within this category, such as an action to quiet title. The essential feature of declaratory relief is that it does not compel an immediate, specific obligation to do something. Such judgments lack an operative command. A money judgment must be paid, although the enforcement of that obligation may prove difficult for the plaintiff (judgment creditor). An injunction must be obeyed under penalty of contempt of court. Declaratory relief does not, however, require or demand that the parties do anything. The full effect of the remedy lies in its educative value and the further remedy of a follow up action to enforce the rights, duties, and obligations recognized by the court in the declaratory action. 4 Admittedly the line between a declaratory judgment and an action granting affirmative relief, such as damages, may be minimal in some cases. 5 [g] Punitive Damages Punitive damages are designed to punish a defendant for commission of a legal wrong. A punitive remedy may be essentially freestanding, such as a punitive damages award, 6 or it may be interwoven into the fabric of the remedy itself, as in the case of contempt where the distinction between criminal and civil contempt is often difficult to discern. 7

4 Montana v. United States, 440 U.S. 147, 157-58, 99 S. Ct. 970, 59 L. Ed. 2d 210 (1979) (declaratory judgment has precedental and collateral estoppel effect). 5 Green v. Mansour, 474 U.S. 64, 67, 106 S. Ct. 423, 88 L. Ed. 2d 371(1985) (declaratory judgment against state would be equivalent of money judgment barred by the Eleventh Amendment because doctrine of res judicata and absence of continuing violation would give declaration only retroactive application); but cf. Steffel v. Thompson, 415 U.S. 452, 480, 94 S. Ct. 1209, 39 L. Ed. 2d 505 (1974) (Rhenquist, J. concurring) (stating that issuance of injunction against state court prosecution should not occur as a matter of course after declaratory judgment that statute under which plaintiff would be prosecuted by state officials was unconstitutional). 6 Chapter 18 (Punitive Damages). 7 Chapter 19 (Contempt). (Matthew Bender & Co., Inc.) (Pub.586)

2[h]

INTRODUCTION TO REMEDIES

Because punitive damages are designed to punish, there is no need to assess whether they will restore or return the plaintiff to the position he would have occupied but for the defendants wrongful conduct. On the other hand, a compensatory damages award may have what can only be described as a punitive component. 8 In this context, the restoration or return of the plaintiff to the position he would have occupied but for defendants wrongful conduct is combined with the desire to punish the defendant. The line separating punitive from compensatory damages is further blurred by the existence of certain limitations on punitive awards that require courts to examine the actual nature of the award to ensure that the limitation is not evaded by artful labeling. For example, in United States v. Halper 9 the Court held that the imposition of civil, money penalties may in certain circumstances violate the Double Jeopardy Clause. 10 Similarly, in Johnson v. Securities Exchange Commission 11 the court held that a nonmonetary sanction in the form of a suspension was punitive in nature. 12 A punitive remedy need not be labeled as such. Treble damage remedies are usually characterized as punitive in part. 13 Similarly, civil forfeiture remedies may be seen as punitive in character. 14 [h] Nominal Damages Nominal damages are designed to remedy violations of legal rights which cause no measurable actual loss or substantial injury. Allowing a plaintiff to claim nominal damages permits the plaintiff to secure a public vindication of her legal claim. 15 The

Section 7[b] (Harsh and Mild Measures). 490 U.S. 435, 109 S. Ct. 1892, 104 L. Ed. 2d 587 (1989). 10 490 U.S. at 447-48. The ruling was later modified in Hudson v. United States, 522 U.S. 93, 118 S. Ct. 488, 139 L. Ed. 2d 450 (1997) (holding that double jeopardy clause only prohibits multiple criminal punishments for the same offense and then only when multiple punishment occurs in successive proceedings). The Court in Hudson held that whether a penalty is civil or criminal is primarily a legislative function and only the clearest proof will suffice to override legislative intent and transform what has been denominated a civil remedy into a criminal penalty. 118 S. Ct. at 493 (citations omitted). 11 87 F.3d 484 (D.C. Cir. 1996). 12 Id. at 488-89; but see United States v. Merriam, 108 F.3d 1162, 1164 (9th Cir. 1997) (statutory bar against acting as broker-dealer imposed as a result of settlement was not punitive for purposes of the Double Jeopardy Clause), cert. denied, 118 S. Ct. 69 (1997). 13 Section 305[a] (Augmented Damages and Punitive Damages). 14 Compare Austin v. United States, 509 U.S. 602, 619, 113 S. Ct. 2801, 125 L. Ed. 2d 488 (1993) (treating in rem civil forfeiture as punishment for purposes of 8th Amendment excess fines clause); with United States v. Ursery, 518 U.S. 267, 286-87, 116 S. Ct. 2135, 135 L. Ed. 2d 549 (1996) (treating in rem civil forfeiture as not being punishment for purposes of double jeopardy). The Court noted, however, that in some cases a civil penalty could be so punitive either in purpose or effect as to constitute criminal punishment for double jeopardy purposes. 518 U.S. at 289 n.3. 15 Farrar v. Hobby, 506 U.S. 103, 121, 113 S. Ct. 566, 121 L. Ed. 2d 494 (1992) (OConnor, J., concurring) (noting [n]ominal relief does not necessarily a nominal victory make; . . . an award of nominal damages can represent a victory in the sense of vindicating rights even though no actual damages are proved).

9 (Matthew Bender & Co., Inc.) (Pub.586) 8

UNDERSTANDING REMEDIES

2[i]

cost is the expense and use of judicial and legal resources in a case where no actual loss or injury has occurred. Although the issue of the advisability of awarding nominal damages would appear to provoke some debate, the propriety of awarding nominal damages has been largely ignored. 16 It may be that nominal damages preserves a desirable status quo. The plaintiff whose legal rights were invaded, but who suffered no loss or injury, other than the awareness of the invasion, is recognized as the prevailing party. Thus, the legal system does not discourage such litigation or add injury to insult by requiring the plaintiff to pay the defendants litigation expenses, which would be the case in the absence of the nominal damages remedy because the defendant would then be the prevailing party. Nominal damages are available in a wide variety of actions, including breach of contract, 17 negligence, 18 constitutional 19 and business 20 torts. Because an award of nominal damages will support an award of attorneys fees and costs in civil rights litigation, some attention has been devoted to the propriety of a plaintiff requesting only an award of nominal damages. 21 [i] Presumed Damages Presumed damages originated in defamation actions. Words which were libelous were reasonably expected to cause harm by their use; thus, they were deemed actionable per se. 22 The cause of action did not require the plaintiff to prove that the publication of

16 But see Bradley v. American Smelting and Ref. Co., 104 Wash. 2d 677, 709 P.2d 782, 790 (1985) (requiring that when the plaintiff seeks recovery under a theory of trespass for airborne particles intruding onto his land, the plaintiff must prove actual injury). This requirement is inconsistent with the general rule that for trespass to land injury is presumed and the plaintiff may collect nominal damages as a matter of course. Ligo v. Gerould, 244 A.D.2d 852, 665 N.Y.S.2d 223, 224 (1997); Snow v. City of Columbia, 305 S.C. 544, 409 S.E.2d 797, 802 (Ct. App. 1991). 17 Scobell, Inc. v. Schade, 455 Pa. Super. 414, 688 A.2d 715, 719 (1997); Magu Realty Co. v. Spartan Concrete Corp., 239 A.D.2d 469, 658 N.Y.S.2d 45, 45 (1997). 18 Nick v. Baker, 125 N.C. App. 568, 481 S.E.2d 412, 414 (1997); contra Bird v. Rozier, 948 P.2d 888, 892 (Wyo. 1997) (holding that [n]ominal damages, to vindicate a technical right, cannot be recovered in a negligence action, where no actual loss has occurred). 19 Carey v. Piphus, 435 U.S. 247, 266-67, 98 S. Ct. 1042, 55 L. Ed. 2d (1978); Muhammad v. Lockhart, 104 F.3d 1069, 1070 (8th Cir. 1997). 20 United States Football League v. National Football League, 842 F.2d 1335, 1377 (2d Cir. 1988) (antitrust action). See also Lodise v. Lodise, 9 F.3d 108 (6th Cir. 1993) (credit report improperly obtained but not used for improper purpose) (unpublished disposition) (1993 WL 441787). 21 Farrar, 506 U.S. at 115 (plaintiffs who recovered only nominal damages on claim for $17 million in damages were not entitled to attorneys fee award under civil rights statute); Section 332 (Prevailing Party). 22 There is some disagreement whether presumed damages applied to all libel actions or only libel per se. Lawrence Eldredge, The Spurious Rule of Libel Per Quod, 79 Harv. L. Rev. 733 (1966); William Prosser, Libel Per Quod, 46 Va. L. Rev. 839 (1960). See also Biondi v. Nassimos, 300 N.J. Super. 148, 692 A.2d 103, 106 (1997) (applying principle to slander per se); Chapter 13 (Remedies for Injury to Reputation). (Matthew Bender & Co., Inc.) (Pub.586)

2[i]

INTRODUCTION TO REMEDIES

the libel caused any harm to reputation or injury to the plaintiff. 23 Although the presumed damages rule was pegged to a causal relationship between act and harm, it is also clear that the rule was rooted in a realization that actual damage, while likely, would be a difficult proof. It is the combination of the causal element and the difficulty of proof that informs modern courts as to when presumed damages may be awarded. 24 The doctrine of presumed damages in the common law of defamation per se has been referred to as an oddity of tort law, for it allows recovery of purportedly compensatory damages without evidence of actual loss. 25 Notwithstanding the backhanded complement, the doctrine of presumed damages has been recognized in other contexts, such as trespass 26 and certain forms of invasion of privacy. 27 The doctrine has received a mixed reception in the context of constitutional torts. The Supreme Court in Carey v. Piphus 28 stated that whether a constitutional tort would support an award of presumed damages depended on the nature of the constitutional right at issue. 29 In Carey the Court rejected a claim of presumed damages when only procedural due process claims were involved. In Memphis Community School District v. Stachura, 30 the Court extended this proscription to First Amendment claims. 31 Nonetheless, lower courts have evidenced a general willingness to apply the presumed damages rule to cases not expressly foreclosed by Supreme Court holdings. To this extent the Court itself has been somewhat ambivalent. 32

Sisler v. Gannett Co., Inc., 104 N.J. 256, 516 A.2d 1083, 1096 (1986). Memphis Community Sch. Dist. v. Stachura, 477 U.S. 299, 310-11, 106 S. Ct. 2537, 91 L. Ed. 2d 249 (1986) (presumed damages may be appropriate when injury is likely but difficult to prove). 25 Gertz v. Robert Welch, Inc., 418 U.S. 323, 349, 94 S. Ct. 2997, 41 L. Ed. 2d 789 (1974). The availability of presumed damages in defamation cases has been restricted due to First Amendment concerns. 418 U.S. at 349-50; see Section 210[b] (Presumed Damages). 26 Gross v. Capital Elec. Line Builders, Inc., 253 Kan. 798, 861 P.2d 1326, 1329 (1993) (rule of presumed damages recognized when trespass constitutes tangible invasion, but not recognized when invasion is intangible, i.e., airborne pollution). See also Bradley, 709 P.2d at 790 (same). 27 Nolley v. County of Erie, 802 F. Supp. 898, 903 (W.D.N.Y. 1992) (presumed damages are appropriate in a cause of action founded on the unwarranted disclosure of a persons HIV status). 28 435 U.S. 247 (1978). 29 435 U.S. at 262-63. 30 477 U.S. 299 (1986). 31 477 U.S. at 312-13. 32 477 U.S. at 310-11: Presumed damages are a substitute for ordinary compensatory damage, not a supplement for an award that fully compensates the alleged injury. When a plaintiff seeks compensation for an injury that is likely to have occurred but difficult to establish, some form of presumed damages may possibly be appropriate. In those circumstances, presumed damages may roughly approximate the harm that the plaintiff suffered and thereby compensate for harms that may be impossible to measure. As we earlier explained, the instructions at issue in

24 (Matthew Bender & Co., Inc.) (Pub.586) 23

10 3

UNDERSTANDING REMEDIES RELATIONSHIP WITH SUBSTANTIVE LAW

Remedies do not exist in isolation but are bound up with rights, which are creatures of substantive law. While remedies are frequently characterized as procedural for a variety of nomenclature purposes, such as choice of law and retroactive application, 1 the distinction should not be taken too far. The nature of an available remedy is clearly tied to the substantive right at issue. Although the remedy may generically be labeled as damages, or injunctive, or restitutionary, the content of the remedy will be strongly influenced by the nature of the interests that comprise the right. Property rights usually will not support emotional distress claims because the latter are not usually seen as part of the bundle of interests that comprise the former. That approach may seem counterintuitive to a layperson who is told that the defendant, whose neglect caused the loss of Fido, the beloved household pet, need not respond to the distress the loss has caused. 2 But unless the substantive bundle of interests is defined to include the owners emotional attachment to property, the remedy will follow the law. While remedies will follow the law, the law will provide appropriate remedies to protect the right. If an injunction is needed to protect a contract right, the remedy of an injunction is available in the form of specific performance. Likewise if an injunction is needed to prevent a trespass or a nuisance, it will be provided. If an injunction is not needed, but damages to redress the violation of a right are, the law will provide such a remedy. The law of remedies is essentially a study of the rules and principles that have been developed to determine how much redress a person is entitled to once a right has been violated. 3 The importance of the right will influence the courts desire to find a remedy. Not surprisingly it has been noted that courts will be alert to adjust their remedies so as to grant the necessary relief for the safeguarding of protected rights. 4 By the same token,

this case did not serve this purpose, but instead called on the jury to measure damages based on a subjective evaluation of the importance of particular constitutional values. Since such damages are wholly divorced from any compensatory purpose, they cannot be justified as presumed damages. (Citations omitted). See also Section 216 (Civil Rights). 1 16 Am. Jur. 2d Conflict of Laws 137 (1979). This was an area where the decisional law was, and remains, in substantial flux over the proper characterization of remedies for choice of law purposes. See Robert Leflar, Luther McDougal, and Robert Felix, American Conflicts Law 126 (4th ed. 1986). The modern trend has been to reject the substance-procedure distinction in this area due to inconsistency in the characterization of the issue and the perception that the distinction was unworkable. See William Richman and William Reynolds, Understanding Conflict of Laws 57, at 155 (2d ed. 1993). The traditional rule is that legislation would be construed as operating prospectively absent express language to the contrary, but this rule did not apply to statutory remedies. First of Am. Trust Co. v. Armstead, 171 Ill. 2d 282, 664 N.E.2d 36, 39 (1996) (criticizing traditional approach). 2 Section 71 (Property With No Martket Value). 3 United States v. Sanchez, 917 F. Supp. 29, 34 (D.D.C. 1996) (noting that while courts must ensure that for every right there is a remedy . . . courts need not provide for every right the same remedy ) (citations omitted). 4 Bivens v. Six Unknown Named Agents of Fed. Bureau of Narcotics, 403 U.S. 388, 392, 91 S. Ct. 1999, 29 L. Ed. 2d 619 (1971).

(Matthew Bender & Co., Inc.) (Pub.586)

INTRODUCTION TO REMEDIES

11

judicial reluctance to recognize or protect a right may be demonstrated by a courts refusal to provide a remedy for the breach of a right. For example, in Anderson v. St. Francis-St. George Hospital, Inc., 5 the court refused to recognize a distinct action for wrongful prolongation of life. The court recognized the validity of a patients right to refuse and anticipatorily reject life-saving treatment. It also found that the defendant had violated a patients instructions to that effect. Nonetheless, the court refused to permit a suit for damages arising out of the patients later suffering of a stroke. According to the court, it was necessary to show that the unauthorized treatment caused or contributed to the stroke. It was not sufficient to base the claim on the mere breach of instruction given by the patient. Nor was it sufficient merely to demonstrate that a stroke was reasonably foreseeable after the patient had been resuscitated in violation of his instructions. 6 Wrongful life claims have proven to be particularly difficult and troubling for courts. While jurisdictions have recognized a persons right to decide whether to be administered life-saving treatment, as Anderson illustrates, courts have been reluctant to back up the right with an enforceable damages remedy. On the other hand, injunctive relief compelling compliance with the instructions would be recognized. 7 Here we see the rough balancing of interests that can be accommodated through the judicious blending of rights and remedies. Although the same right may be involved, the elements of proof necessary to establish a violation of that right for remedial purposes will vary as the remedy varies. Consider, for example, a person with a transmittable disease who has been terminated from his employment. If he seeks the remedy of an injunction reinstating him to his position, the critical issue has been framed as whether based on the current considered judgment of medical and public health officials, the employee poses a significant risk to others. 8 When, however, the remedy sought is damages, the critical issue is framed as the employees qualifications at the time the separation decision is made. 9 In this regard the relevant inquiry is what the employer knew or should have known at the time he took action against the employee, about whether the employee was otherwise qualified to perform his job.

77 Ohio St. 3d 82, 671 N.E.2d 225 (1996). 671 N.E.2d at 229: We also observe that unwanted life-saving treatment does not go undeterred. Where a patient clearly delimits the medical measures he or she is willing to undergo, and a health care provider disregards such instructions, the consequences for that breach would include the damages arising from any battery inflicted on the patient, as well as appropriate licensing sanctions against the medical professionals. 7 In re Fiori, 438 Pa. Super. 610, 652 A.2d 1350 (1995); Care and Protection of Beth, 412 Mass. 188, 587 N.E.2d 1377 (1992). 8 School Bd. of Nassau County v. Arline, 480 U.S. 273, 288, 107 S. Ct. 1123, 94 L. Ed. 2d 307 (1987); Chalk v. United States Dist. Court, 840 F.2d 701, 707-09 (9th Cir. 1988). 9 Mantolete v. Bolger, 767 F.2d 1416, 1422 (9th Cir. 1985); cf. Teahan v. Metro-North Commuter R.R., Inc., 951 F.2d 511, 519 (2d Cir. 1991), cert. denied, 506 U.S. 815 (1992).

6 (Matthew Bender & Co., Inc.) (Pub.586) 5

12 4

UNDERSTANDING REMEDIES PUBLIC POLICY

Lord Justice Burrough, when asked to invalidate a contract on public policy grounds, stated that public policy is a very unruly horse, and once you get astride it you never know where it will carry you. 1 Other judges have expressed a more accepting role for public policy. 2 While public policy considerations are usually derived from constitutions and statutes, an act may be declared violative of public policy through judicial discretion. 3 The conflicting judicial attitudes toward the role of public policy in decision making tends toward three considerations. First, expressions of public policy are usually made as broad generalizations. Thus, it is frequently said that a person should not be permitted to profit from his own wrongdoing, 4 or that whether a contract violates public policy turns on whether the contract as made has a tendency to evil, to be against the public good, or be injurious to the public. 5 The second consideration flows from the first: Broad generalizations prove exceptionally difficult to apply with regularity and consistency in practice. The matter is often further complicated by the question whether public policy should be decided by the court 6 or commited to the jury. 7

Richardson v. Mellish, 2 Bing. 229, 130 Eng. Rep. 294, 303 (Comm. Pleas 1824). See also Norwest v. Presbyterian Intercommunity Hosp., 293 Or. 543, 652 P.2d 318, 323-24 (1982) (noting courts inherent limitations in gauging and weighing competing social interests presented as policy considerations). 2 Pittsburg C, C & St. L.R. Co. v. Kinney, 95 Ohio St. 64, 115 N.E. 505, 507 (1916): Public policy is the cornerstonethe foundation&mdash&of all constitutions, statutes, and judicial decisions, and its latitude and longitude, its height and its depth, greater than any or all of them. If this be not true, whence came the first judicial decision on matter of public policy? There was no precedent for it, else it would not have been the first. 3 Pittsburg C, C & St. L.R. Co. v. Kinney, 95 Ohio St. 64, 115 N.E. 505, 507 (1916) (Sometimes such public policy is declared by Constitution; sometimes by statute; sometimes by judicial decision. More often, however, it abides only in the customs and conventions of the peoplein their clear consciousness and conviction of what is naturally and inherently just and right between man and man). See also Petrillo v. Syntex Labs., Inc., 148 Ill. App. 3d 581, 499 N.E.2d 952, 956 (1986), cert. denied, sub nom. Tobin v. Petrillo, 483 U.S. 1007 (1987). 4 Barker v. Kallash, 63 N.Y.2d 19, 479 N.Y.S.2d 201, 468 N.E.2d 39, 41 (1984) (voluntary participation in an illegal act). 5 Marshall v. Higginson, 62 Wash. App. 212, 813 P.2d 1275, 1278 (1991). See also Petrillo, 499 N.E.2d at 956. 6 Bovard v. American Horse Enters., Inc., 201 Cal. App. 3d 832, 247 Cal. Rptr. 340, 343 (1988) (stating that the illegality of contract is a question of law determined by the judge) (citation omitted). See also Vogel v. Liberty Mut. Ins. Co., 214 Wis. 2d 442, 571 N.W.2d 704, 706 (Ct. App. 1997) (stating that application of public policy factors to determine existence of liability in tort is a function of the court). 7 17A Am. Jur. 2d Contracts 335, p.340 (1991) (stating that illegality of contract is question of fact for jury when determination whether contract violates public policy depends on circumstances or parties intent).

(Matthew Bender & Co., Inc.) (Pub.586) 1

INTRODUCTION TO REMEDIES

13

Lastly, public policy issues are rarely unidirectional; rather, they tend to raise competing considerations. For example, the public policy in compensating individuals for anothers tortious infliction of emotional distress may conflict with the public policy that the intimacies of family life should be preserved against routine litigation when the parties are husband and wife. 8 The intersect of these considerations tends to turn many invocations of public policy into a surrogate for a balancing or cost/benefit oriented analysis. 9 Public policy claims are best established when tied to a statute from which a legislative policy can be discerned. In these contexts, courts will apply the inferred public policy standards to the case before them. 10 The results can, on occasion, be quite startling. For example, in Hydrotech Systems Ltd. v. Oasis Waterpark 11 the court refused to allow an unlicensed contractor to recover any remedies for work performed for which a license was required. Refusing an unlicensed party from recovering the contract price is seen as consistent with the statutory scheme creating the license requirement in the first place. The court went on to hold, however, that the public policy behind the licensure requirement not only foreclosed a quantum meruit recovery for the value of any benefit realized by the party who hired the unlicensed contractor, but that public policy also foreclosed a promissory fraud claim that the hiring party retained the unlicensed contractor specifically because he knew the contractor was unlicensed and had no intention of paying for the services. 12 The public policy horse can be not only unruly but occasionally stubborn. Public policy concerns are often tied to concrete issues that can give public policy considerations a conservative rather than activist tone. For example, the absence of acceptable and easily applicable standards or the fear of opening a floodgate of litigation have been asserted as public policy reasons for not providing a remedy. 13 On other occasions the court may simply treat the wrong as de minimis:

Hakkila v. Hakkila, 112 N.M. 172, 812 P.2d 1320, 1323-24, 1326 (Ct. App. 1991). Koestler v. Pollard, 162 Wis. 2d 797, 471 N.W.2d 7, 12 (1991) (Public policy bars Koestlers claim because more harm than good will result if Koestler is allowed to pursue this action). See also Christensen v. Eggen, 562 N.W.2d 806, 810 (1997): In determining whether an agreement violates public policy, courts employ a balancing test, weighing public policy favoring freedom of contract against policy favoring observance of the duty allegedly breached by a contracting party. A value of great public importance may outweigh the countervailing public policy favoring freedom in negotiating contracts. (Citations omitted). 10 Weicker v. Weicker, 22 N.Y.2d 8, 290 N.Y.S.2d 732, 237 N.E.2d 876, 876-77 (1968). 11 52 Cal. 3d 988, 803 P.2d 370 (1991). 12 803 P.2d at 376: Regardless of the equities, section 7031 bars all actions, however they are characterized, which effectively seek compensation for illegal unlicensed contract work. Thus, an unlicensed contractor cannot recover either for the agreed contract price or for the reasonable value of labor and materials. The statutory prohibition operates even where the person for whom the work was performed knew the contractor was unlicensed. (Citations omitted). 13 Ross v. Creighton Univ., 957 F.2d 410, 414 (7th Cir. 1992) (educational malpractice); Section 221 (Educational Malpractice).

9 (Matthew Bender & Co., Inc.) (Pub.586) 8

14

UNDERSTANDING REMEDIES

There are many wrongs which in themselves are flagrant. For instance, such wrongs as betrayal, brutal words, and heartless disregard of the feelings of others are beyond any effective legal remedy and any practical administration of law . . . . To attempt to correct such wrongs or give relief from their effects may do more social damage than if the law leaves them alone. 14

14 Richard P. v. Superior Court, 202 Cal. App. 3d 1089, 249 Cal. Rptr. 246, 249 (1988) (citations omitted) (rejecting tort claims by husband against another man for fathering two children with plaintiffs wife during plaintiff and his wifes marriage); Section 203[c] (Fraud and Personal Relationships).

(Matthew Bender & Co., Inc.)

(Pub.586)

You might also like

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Credit Card Arrangements as Loan ContractsDocument2 pagesCredit Card Arrangements as Loan ContractsKylie GavinneNo ratings yet

- Ome 664: Project Procurement & Contracting: Lecture 7: Contract Management and ControlDocument42 pagesOme 664: Project Procurement & Contracting: Lecture 7: Contract Management and ControlYonas AlemayehuNo ratings yet

- Commercial Suit Rejection ApplicationDocument32 pagesCommercial Suit Rejection Applicationdushyant bhargavaNo ratings yet

- American Home Assurance v. Tantuco Scire LicetDocument2 pagesAmerican Home Assurance v. Tantuco Scire LicetJetJuárezNo ratings yet

- Casket Makers Entitled to OT, Holiday, SIL and 13th Month PayDocument2 pagesCasket Makers Entitled to OT, Holiday, SIL and 13th Month Paymei atienzaNo ratings yet

- (A) Coercion: Free ConsentDocument12 pages(A) Coercion: Free ConsentAshish SinghNo ratings yet

- PRINCE2 PractitionerDocument222 pagesPRINCE2 PractitionerStanley Ke Bada100% (1)

- Pitching and Negotiation Skills: Instructor: Amna ZahoorDocument32 pagesPitching and Negotiation Skills: Instructor: Amna ZahoorSyed Ammad AliNo ratings yet

- Lnvestor Updates (Company Update)Document35 pagesLnvestor Updates (Company Update)Shyam SunderNo ratings yet

- Contractual CapacityDocument5 pagesContractual CapacitySameer SawantNo ratings yet

- 2 Multi-Realty Vs Makati TuscanyDocument21 pages2 Multi-Realty Vs Makati TuscanyLaura MangantulaoNo ratings yet

- Raj Shekhar Attri, J. (President), Padma Pandey and Rajesh K. Arya, MembersDocument7 pagesRaj Shekhar Attri, J. (President), Padma Pandey and Rajesh K. Arya, MembersAnany UpadhyayNo ratings yet

- CarteDocument285 pagesCarteSandu Alexandru DanielNo ratings yet

- Cell Management (5G RAN3.1 - 01)Document51 pagesCell Management (5G RAN3.1 - 01)VVLNo ratings yet

- IMO Consultant Information BookletDocument23 pagesIMO Consultant Information BookletringboltNo ratings yet

- Exam Evaluation Intermediate. Mițcul OxanaDocument3 pagesExam Evaluation Intermediate. Mițcul OxanaKsiusha MitculNo ratings yet

- Contract To Sell Rochelle CudiamatDocument4 pagesContract To Sell Rochelle CudiamatNhel CudiamatNo ratings yet

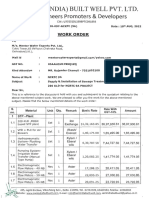

- Work Orders STPDocument112 pagesWork Orders STPRajender Chamoli100% (1)

- Obligations and Contracts Reviewer AteneoDocument27 pagesObligations and Contracts Reviewer AteneoPhoebe PuaNo ratings yet

- Rojales v. DimeDocument2 pagesRojales v. DimeAlfonso Miguel DimlaNo ratings yet

- Lao Sok Vs Sabaysabay DigestDocument2 pagesLao Sok Vs Sabaysabay DigestMichelle Ann AsuncionNo ratings yet

- View Completed FormsDocument8 pagesView Completed FormsDragos PopaNo ratings yet

- ALDOT Cooper BriefDocument51 pagesALDOT Cooper BriefErica ThomasNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Seventh CircuitDocument10 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Seventh CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Petitioner Vs Vs Respondent Albert M. Rasalan The Solicitor GeneralDocument21 pagesPetitioner Vs Vs Respondent Albert M. Rasalan The Solicitor GeneralCinja ShidoujiNo ratings yet

- 03 - Attachment-8-Manufacturer Authorization FormDocument1 page03 - Attachment-8-Manufacturer Authorization FormPOWERGRID FARIDABAD PROJECTNo ratings yet

- Popular Industries v Eastern Garment Manufacturing Contract Breach and Damages Case AnalysisDocument14 pagesPopular Industries v Eastern Garment Manufacturing Contract Breach and Damages Case Analysisnurulashikin mursid0% (1)

- Spa SBLC of BangpanDocument13 pagesSpa SBLC of BangpanVimala sithiphonmekNo ratings yet

- Note About PPADocument28 pagesNote About PPAeph50% (2)

- 821 (2014) 1 CLJ AV Asia SDN BHD v. Measat Broadcast Network Systems SDN BHDDocument17 pages821 (2014) 1 CLJ AV Asia SDN BHD v. Measat Broadcast Network Systems SDN BHDsyakirahNo ratings yet