Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Abueg Vs

Uploaded by

Roms AvilaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Abueg Vs

Uploaded by

Roms AvilaCopyright:

Available Formats

Abueg vs. San Diego (CA-773-775, 17 December 1946) Also de Salvacion vs. San Diego, and Oching vs.

Sand Diego En Banc, Padilla (J): 8 concur Facts: The M/S San Diego II and the M/S Bartolome, both belonging to Bartolome San Diego, while engagedin fishing operations around Mindoro Island on 1 October 1941 were caught by a typhoon as a consequenceof which they were sunk and totally lost. Amado Nuez (machinist on board M/S San Diego II), VictorianoSalvacion (machinist on board M/S Bartolome S) and Francisco Oching (captain or patron of M/S BartolomeS) while acting in their capacities perished in the shipwreck. Said vessels were not covered by any insurance.Dionisia Abueg, widow of Amado Nuez; Marciana S. de Salvacion, widow of Victoriano Salvacion; andRosario R. Oching, widow of Francisco Oching, filed before the CFI of Manila an action for compensationas provided for in the Workmens Compensation Act. The trial court awarded said compensation to the widows.Hence, the appeal to the Court of Appeals. As there was no question of fact involved in the appeal, theappellate court forwarded the record to the Supreme Court. The appeal was pending when the Pacific War broke out, and continued pending until afterliberation, becausethe record of the cases was destroyed as a result of the battle waged by the forces of liberation against theenemy. As provided by law, the record was reconstituted and the Supreme Court proceeded to dispose of theappeal. Finding no merit in the appeal filed in the cases, the Supreme Court affirmed the judgment of thelower court, with costs against San Diego.

Planters product vs ca FACTS:

June 16 1974: Mitsubishi International Corporation (Mitsubishi) of New York, U.S.A., 9,329.7069 M/T of Urea 46% fertilizer bought by Planters Products, Inc. (PPI) on aboard the cargo vessel M/V "Sun Plum" owned by private Kyosei Kisen Kabushiki Kaisha (KKKK) from Kenai, Alaska, U.S.A., to Poro Point, San Fernando, La Union, Philippines, as evidenced by Bill of Lading May 17 1974: a time charter-party on the vessel M/V "Sun Plum" pursuant to the Uniform General Charter was entered into between Mitsubishi as shipper/charterer and KKKK as shipowner, in Tokyo, Japan Before loading the fertilizer aboard the vessel, 4 of her holds were all presumably inspected by the charterer's representative and found fit The hatches remained closed and tightly sealed throughout the entire voyage July 3, 1974: PPI unloaded the cargo from the holds into its steelbodied dump trucks which were parked alongside the berth, using metal scoops attached to the ship, pursuant to the terms and conditions of the charterpartly o hatches remained open throughout the duration of the discharge

Each time a dump truck was filled up, its load of Urea was covered with tarpaulin before it was transported to the consignee's warehouse located some 50 meters from the wharf o Midway to the warehouse, the trucks were made to pass through a weighing scale where they were individually weighed for the purpose of ascertaining the net weight of the cargo. o The port area was windy, certain portions of the route to the warehouse were sandy and the weather was variable, raining occasionally while the discharge was in progress. o Tarpaulins and GI sheets were placed in-between and alongside the trucks to contain spillages of the ferilizer o It took 11 days for PPI to unload the cargo Cargo Superintendents Company Inc. (CSCI), private marine and cargo surveyor, was hired by PPI to determine the "outturn" of the cargo shipped, by taking draft readings of the vessel prior to and after discharge o shortage in the cargo of 106.726 M/T and that a portion of the Urea fertilizer approximating 18 M/T was contaminated with dirt Certificate of Shortage/Damaged Cargo prepared by PPI o short of 94.839 M/T and about 23 M/T were rendered unfit for commerce, having been polluted with sand, rust and dirt PPI sent a claim letter 1974 to Soriamont Steamship Agencies (SSA), the resident agent of the carrier, KKKK, for P245,969.31 representing the cost of the alleged shortage in the goods shipped and the diminution in value of that portion said to have been contaminated with dirt o SSA: what they received was just a request for shortlanded certificate and not a formal claim, and that they "had nothing to do with the discharge of the shipment RTC: failure to destroy the presumption of negligence against them, SSA are liable CA: REVERSED - failed to prove the basis of its cause of action

o

ISSUE: W/N a time charter between a shipowner and a charterer transforms a common carrier into a private one as to negate the civil law presumption of negligence in case of loss or damage to its cargo HELD: NO. petition is DISMISSED

When PPI chartered the vessel M/V "Sun Plum", the ship captain, its officers and compliment were under the employ of the shipowner and therefore continued to be under its direct supervision and control. Hardly then can we charge the charterer, a stranger to the crew and to the ship, with the duty of caring for his cargo when the charterer did not have any control of the means in doing so carrier has sufficiently overcome, by clear and convincing proof, the prima facie presumption of negligence. The hatches remained close and tightly sealed while the ship was in transit as the weight of the steel covers made it impossible for a person to open without the use of the ship's boom.

bulk shipment of highly soluble goods like fertilizer carries with it the risk of loss or damage. More so, with a variable weather condition prevalent during its unloading o This is a risk the shipper or the owner of the goods has to face. Clearly, KKKK has sufficiently proved the inherent character of the goods which makes it highly vulnerable to deterioration; as well as the inadequacy of its packaging which further contributed to the loss. o On the other hand, no proof was adduced by the petitioner showing that the carrier was remise in the exercise of due diligence in order to minimize the loss or damage to the goods it carried.

Planters Products vs. CA (GR 101503, 15 September 1993) First Division, Bellosillo (J): 2 concur, 1 on leave, 1 took no part Facts: Planters Products, Inc. (PPI), purchased from Mitsubishi International Corporation of New York, USA, 9,329.7069 metric tons (M/T) of Urea 46% fertilizer which the latter shipped in bulk on 16 June 1974 aboardthe cargo vessel M/V Sun Plum owned by Kyosei Kisen Kabushiki Kaisha (KKKK) from Kenai, Alaska,USA, to Poro Point, San Fernando, La Union, Philippines, as evidenced by Bill of Lading KP-1 signed by themaster of the vessel and issued on the date of departure. On 17 May 1974, or prior to its voyage, a timecharter-party on the vessel M/V Sun Plum pursuant to the Uniform General Charter was entered intobetween Mitsubishi as shipper/charterer and KKKK as shipowner, in Tokyo, Japan. Riders to the aforesaidcharter-party starting from paragraph 16 to 40 were attached to the pre-printed agreement.Addenda 1, 2, 3and 4 to the charter-party were also subsequently entered into on the 18th, 20th, 21st and 27th of May 1974, respectively. Before loading the fertilizer aboard the vessel, 4 of her holds were all presumably inspected bythe charterers representative and found fit to take a load of urea in bulk pursuant to paragraph 16 of thecharter-party. After the Urea fertilizer was loaded in bulk by stevedores hired by and under the supervision ofthe shipper, the steel hatches were closed with heavy iron lids, covered with 3 layers of tarpaulin, then tiedwith steel bonds. The hatches remained closed and tightly sealed throughout the entire voyage. Upon arrivalof the vessel at her port of call on 3 July 1974, the steel pontoon hatches were opened with theuse of the vessels boom. PPI unloaded the cargo from the holds into its steel-bodied dump trucks which were parkedalongside the berth, using metal scoops attached to the ship, pursuant to the terms and conditions of thecharter-party (which provided for an FIOS clause). The hatches remained open throughout the duration of thedischarge. Each time a dump truck was filled up, its load of Urea was covered with tarpaulin before it wastransported to the consignees warehouse located some 50 meters from the wharf. Midway to the warehouse,the trucks were made to pass through a weighing scale where they were individually weighed for the purpose of ascertaining the net weight of the cargo. The port area was windy, certain portions of theroute to thewarehouse were sandy and the weather was variable, raining occasionally while the discharge was inprogress. PPIs warehouse was made

of corrugated galvanized iron (GI) sheets, with an opening at the frontwhere the dump trucks entered and unloaded the fertilizer on the warehouse floor. Tarpaulins and GI sheetswere placed in-between and alongside the trucks to contain spillages of the fertilizer. It took 11 days for PPI to unload the cargo, from 5 July to 18 July 1974 (except July 12th, 14th and 18th). A private marine andcargo surveyor, Cargo Superintendents Company Inc. (CSCI), was hired by PPI to determine the outturn ofthe cargo shipped, by taking draft readings of the vessel prior to and after discharge. The survey reportsubmitted by CSCI to the consignee (PPI) dated 19 July 1974 revealed a shortage in the cargo of 106.726 M/Tand that a portion of the Urea fertilizer approximating 18 M/T was contaminated with dirt. The same resultswere contained in a Certificate of Shortage/Damaged Cargo dated 18 July 1974 prepared by PPI which showed that the cargo delivered was indeed short of 94.839 M/T and about 23 M/T wererendered unfit forcommerce, having been polluted with sand, rust and dirt. Consequently, PPI sent a claim letter dated 18December 1974 to Soriamont Steamship Agencies (SSA), the resident agent of the carrier, KKKK, forP245,969.31 representing the cost of the alleged shortage in the goods shipped and the diminution in value ofthat portion said to have been contaminated with dirt. SSA explained that they were not able to respond to the consignees claim for payment because, according to them, what they received was just a request forshortlanded certificate and not a formal claim, and that this request was denied by them because they hadnothing to do with the discharge of the shipment. On 18 July 1975, PPI filed an action for damages with the Court of First Instance of Manila. The court a quohowever sustained the claim of PPI against the carrier for the value of the goods lost or damaged.On appeal, the Court of Appeals reversed the lower court and absolved the carrier from liability for the valueof the cargo that was lost or damaged. PPI appealed by way of petition for review.The Supreme Court dismissed the petition; affirmed the assailed decision of the Court of Appeals, whichreversed the trial court; and consequently, dismissed Civil Case 98623 of thethen CFI, now RTC, of Manila;with costs against PPI.

Market Developers vs. IAC (GR 74978, 8 September 1989) First Division, Cruz (J): 4 concur Facts: On 20 June 1978, Market Developers, Inc. (MADE) entered into a written barging and towage contractwith Gaudioso Uy for the shipment of the formers cargo from Iligan City to Kalibo, Aklan, at the rate ofP1.45 per bag. MADE was allowed 4 lay days and agreed to pay demurrage at the rate of P5,000.00 for everyday of delay, or in excess of the stipulated allowance. On 26 June 1978, Uy sent a barge and a tugboat toIligan City and loading of MADEs cargo began immediately. It is not clear who made the request, but upon completion of the loading on 29 June 1978, the parties agreed to divert the barge to Culasi, Roxas City, withthe cargo being consigned per bill of lading to Modern Hardware in that city. This new agreement was notreduced to writing. The shipment arrived in Roxas City on 13 July 1978, and the cargo waseventuallyunloaded and duly received by the consignee. There is some dispute

as to the time consumed for suchunloading. At any rate, about 6 months later, Uy demanded payment of demurrage charges in the sum ofP40,855.40 for an alleged delay of 8 days and 4/25 hours. MADE ignored this demand, and Uy filed suit. Uy was sustained by the trial court, which ordered MADE to pay him the said amount with interest plusP4,000.00 attorneys fees and the cost of the suit. This decision was fully affirmed on appeal to theIntermediate Appellate Court. Hence, the petition. The Supreme Court granted the petition; reversed the decision of the appellate court; and dismissed CivilCase R 18095 in the RTC of Cebu, with costs against Uy. 1. First written contract cancelled and replaced by second verbal contract After considering the issues and the arguments of the parties, the Court finds that it was erroneous forthe trial and appellate courts to affirm that the original contract concluded on 20 June 1978, continued toregulate the relations of the parties. What it should have held instead was that the first written contract hadbeen cancelled and replaced by the second verbal contract because of the change in the destination of the cargo. Although the rates remained unchanged at P1.45 per sack of MADEs cargo, there was a substantialdifference between Roxas City and Kalibo, Aklan, as ports of destination, that affected the continuedexistence of the first contract. 2. Roxas City a busier port than Kalibo; Demurrer charges not contemplated in second contract Roxas City is a much busier port than Kalibo, Aklan, where unloading of its cargo could have beenaccomplished faster because of the lighter traffic. That is why MADE agreed to pay demurrage charges underthe original contract but not under the revised verbal agreement. Indeed, it would have been foolhardy forMADE to assume demurrage charges in Roxas City, considering the crowded condition of the port in thatplace. Such assumption should not have been lightly inferred, especially since it is based on the resurrectionof a contract already voided because of the change in the port of destination. To hold that the old agreementwas still valid and subsisting notwithstanding this substantial change wawas to impose upon MADE a conditionhe had not, and would not have, accepted under the new agreement.

Iron Bulk Shipping Phils. Co. LTD. vs Remington Industrial Sales Corp. (2003) Iron Remington Industrial Sales Corp. Ordered from Wangs Co. 194 packages of hot steel sheets .Goods were loaded on board vessel MV Indian Reliance from Poland upon issuance of a clean Bill of Lading. However, upon arrival in Manila, they were already rusty. Remington sued Iron BulkShipping and insurer Pioneer Asia insurance. The court ruled for Remington relying on the Bills of Lading which stated that the goods were in good condition when loaded. Iron Bulks assails thereliance of the court on the Pro Forma Bills of Lading in establishing the condition of the cargo. Can aBill of lading be relied upon to indicate the cargo condition upon loading? Held: Yes. There is no merit to petitioner's contention that the Bill of Lading covering the subjectcargo cannot be relied upon to indicate the condition of the cargo upon loading. It is settled that abill of lading has a two-fold character. In Phoenix Assurance Co., Ltd. vs. United States Lines, we heldthat: [A] bill of lading operates both as a receipt and as a contract. It is a receipt for the goodsshipped and a contract to transport and deliver the

same as therein stipulated. As a receipt, it recitesthe date and place of shipment, describes the goods as to quantity, weight, dimensions,identification marks and condition, quality and value. As a contract, it names the contracting parties,which include the consignee, fixes the route, destination, and freight rate or charges, and stipulatesthe rights and obligations assumed by the parties. We find no error in the findings of the appellatecourt that the questioned bill of lading is a clean bill of lading, i.e., it does not indicate any defect inthe goods covered by it, as shown by the notation, "CLEAN ON BOARD" and "Shipped at the Port of Loading in apparent good condition on board the vessel for carriage to Port of Discharge".The fact that the issued bill of lading is pro forma is of no moment. If the bill of lading is not trulyreflective of the true condition of the cargo at the time of loading to the effect that the said cargowas indeed in a damaged state, the carrier could have refused to accept it, or at the least, made amarginal note in the bill of lading indicating the true condition of the merchandise. But it did not. Onthe contrary, it accepted the subject cargo and even agreed to the issuance of a clean bill of ladingwithout taking any exceptions with respect to the recitals contained therein. Since the carrier failedto annotate in the bill of lading the alleged damaged condition of the cargo when it was loaded, saidcarrier and the petitioner, as its representative, are bound by the description appearing therein andthey are now estopped from denying the contents of the said bill.Even granting, for the sake of argument, that the subject cargo was already in a damaged conditionat the time it was accepted for transportation, the carrier is not relieved from its responsibility toexercise due care in handling the merchandise and in employing the necessary precautions toprevent the cargo from further deteriorating. Under Article 1742 of the Civil Code, even if the loss,destruction, or deterioration of the goods should be caused, among others, by the character of thegoods, the common carrier must exercise due diligence to forestall or lessen the loss.EXTRAORDINARY RESPONSIBILITY LASTS FROM THE TIME THE GOODS ARE UNCONDITIONALLYPLACED IN ITS POSSESSION UNTIL THE SAME ARE DELIVERED TO THE CONSIGNEE. UNLESS PROVENTO HAVE BEEN OBSERVED, COMMON CARRIER IS PRESUMED TO HAVE BEEN AT FAULT OR TO HAVEACTED NEGLIGENTLY.

Magsaysay Inc. vs Anastacio Agan In 1949, SS San Antonio, owned by AMInc, embarked on its voyage to Batanes via Aparri. It was carrying various cargoes, one of which was owned by Agan. One fine weather day, it accidentally ran aground the mouth of the Cagayan River due to the sudden shifting of the sands below. SS San Antonio then needed the services of Luzon Stevedoring Co. to tow the ship and make it afloat so that it can continue its journey. Later, AMInc required the cargo owners to pay the expenses incurred in making the ship afloat (P841.40 each). The expenses, AMInc claims, fall under the General Averages Rule under the Code of Commerce, which is to be shared by ship owner and cargo owners as well.

ISSUE: Whether or not general averages exist in the case at bar. HELD: No. General averages contemplate that the stranding of the vessel is intentionally done in order to save the vessel itself from a certain and imminent danger. Here, the stranding was accidental and it was made afloat for the purpose of saving the voyage and not the vessel. Note that this happened on a fine weather day. Also, it cannot be said that the towing was made to save the cargos, for the cargos were not in danger imminent danger.

COMPAGNIE DE COMMERCE ETDE NAVIGATION DEXTREME ORIENT VS . THE HAMBURG AMERIKA PACKET FACHTACTIENG ESELLSCHAFT FACTS:-HAMBURG owned a steamship named SAMBIA, which procee ded to the port of Saigon and was takingthe cargo belonging to COMPAGNIE. Apparently, there were rumors of impending war between Germanyand France and other nations of Europe. The master of the steamship was told to take refuge at a neutral port (because Saigon was a French port). So, to stop that, COMPAGNIE asked for compulsory detention of his vessel to prevent its property from leaving Saigon. However, the Governor of Saigon refused to issue anorder because he had not been officially notified of the declaration of the war.-The steamship sailed from Saigon, and was bound for Manila, because it was issued a bill of health by theUS consul in Saigon. The steamship stayed continuously in Manila and where it contends it will becompelled to stay until the war ceases. No attempt on the part of the defendants to transfer and deliver thecargo to the destinations as stipulated in the charter party. That BEHN, MEYER and COMPANY (agent of HAMBURG in manila) offered to purchase the cargo from COMPAGNIE, but the latter never received thecable messages so they never answered. (obviously)When a survey was done on the ship, it was found that the cargo was *weevily and heating* (whatever that means), so BEHN asked for court authority to sell the cargo and the balance to be dumped at sea. The proceeds of the sale were deposited in the court, waiting for orders as to what to do with it.BEHN wrote COMPAGNIE again informing the latter of the disposition which it made upon the cargo.COMPAGNIE answered that it was still waiting for orders as to what to do.-COMPAGNIE of course wanted all the proceeds of the sale to be given to them (damages for the defendants failure to deliver the cargo to the destinations Dunkirk and Hamburg), while defendantscontend that they have a lien on the proceeds of the sale (amount due to them because of the upkeep andmaintenance of the ship crew and for commissions for the sale of the cargo).- T h e t r i a l c o u r t r u l e d i n f a v o r o f t h e p l a i n t i f f s . -On appeal, the defendants made the ff: assignments on appeal (t hat the court had no jurisdiction, that thefear of capture was not force majeure, that the court erred in concluding that defendant is liable for damages for non-delivery of cargo, and the value of the award of damages)-On appeal, the plaintiffs also conte nded that

the court erred in not giving the full value of damages (kasi binawas un expenses ng mga defendants) ISSUE: WoN the master of the steamship was justified in taking refuge in Manila (therefore being the cause of thenon-delivery of the cargo belonging to the plaintiffs) -COMPAGNIE contends that the master should have in mind the accepted principles of public internationallaw, the established practice of nations, and the express terms of the Sixth Hague Convention (1907), themaster should have confidently relied upon the French authorities at Saigon to permit him to sail to his portof destination under alaissez-passer or safe-conduct, which would have secured both the vessel and her cargo from all danger of capture by any of the belligerents. The SHIPOWNER contends that the master was justified in declining to leave his vessel in a situation in which it would be exposed to danger of seizure bythe French authorities, should they refuse to be bound by the alleged rule of international law. HELD: The Court held that after examining the terms and conditions of the convention that at the outbreak of the present war, there was no such general recognition of the duty of a belligerent to grant "days of grace" and"safe-conducts" to enemy ships in his harbors, as would sustain a ruling that such alleged duty was prescribed by any imperative and well settled rule of public international law, of such binding force that itwas the duty of the master of the Sambia to rely confidently upon a compliance with its terms by theFrench authorities in Saigon.-It was nothing but a *pious wish* at least, adherence to the practice by any belligerent could not be demanded by virtue of any convention, tacit or express, universally recognized by the members of thesociety of nations; and that it may be expected only when the belligerent is convinced that the demand for adherence to the practice inspired by his own commercial and political interests outweighs any advantagehe can hope to gain by a refusal to recognize the practice as binding upon him. The Court concluded that under the circumstances surrounding the flight of the Sambia from the port of Saigon, her master had no such assurances, under any well-settled and universally accepted rule of publicinternational law, as to the immunity of his vessel from seizure by the French authorities, as would justifyus in holding that it was his duty to remain in the port of Saigon in the hope that he would be allowed tosail for the port of destination designated in the contract of affreightment with a laissez-passer or safe-conduct which would secure the safety of his vessel and cargo en route.-The Court also held that it was the duty of the ship -owner to sell, and not to just transship the cargo, due to the fact of the perishable nature of the cargo (rice) and that he was justified in the delay of acting, so as toascertain reasonably what course of action to take.- R E : j u r i s d i c t i o n . I t cannot be raised on appeal for the first time

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Part-II-Philippines Civil-Service-Professional ReviewerDocument25 pagesPart-II-Philippines Civil-Service-Professional ReviewerJanjake Legaspi50% (4)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Budgetary RequirementsDocument1 pageBudgetary RequirementsRoms AvilaNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Philippines Civil Service Professional Reviewer - Part 1Document24 pagesPhilippines Civil Service Professional Reviewer - Part 1Michael L. Dantis50% (2)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- College of Arts and Letters: Republic of The Philippines Bicol University Legazpi CityDocument1 pageCollege of Arts and Letters: Republic of The Philippines Bicol University Legazpi CityRoms AvilaNo ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- TV Prod - Bungcul LetterDocument4 pagesTV Prod - Bungcul LetterRoms AvilaNo ratings yet

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- College of Arts and Letters: Republic of The Philippines Bicol University Legazpi CityDocument1 pageCollege of Arts and Letters: Republic of The Philippines Bicol University Legazpi CityRoms AvilaNo ratings yet

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Extent of Compliance: AdministrationDocument1 pageExtent of Compliance: AdministrationRoms AvilaNo ratings yet

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Telephone DirectoryDocument4 pagesTelephone DirectoryRoms AvilaNo ratings yet

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Table of Contents2.15.16Document18 pagesTable of Contents2.15.16Roms AvilaNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Activities ScheduleDocument1 pageActivities ScheduleRoms AvilaNo ratings yet

- Budget ProposalDocument1 pageBudget ProposalRoms AvilaNo ratings yet

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Afp Evaluation of TrainingDocument4 pagesAfp Evaluation of TrainingRoms AvilaNo ratings yet

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Date of Submission ofDocument1 pageDate of Submission ofRoms AvilaNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Maroon 5Document1 pageMaroon 5Roms AvilaNo ratings yet

- Making/#5dd031981409: 1. Don't DelayDocument17 pagesMaking/#5dd031981409: 1. Don't DelayRoms AvilaNo ratings yet

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Making/#5dd031981409: 1. Don't DelayDocument17 pagesMaking/#5dd031981409: 1. Don't DelayRoms AvilaNo ratings yet

- Making/#5dd031981409: 1. Don't DelayDocument17 pagesMaking/#5dd031981409: 1. Don't DelayRoms AvilaNo ratings yet

- Date andDocument1 pageDate andRoms AvilaNo ratings yet

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Ariana GrandeDocument2 pagesAriana GrandeRoms AvilaNo ratings yet

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Making/#5dd031981409: 1. Don't DelayDocument17 pagesMaking/#5dd031981409: 1. Don't DelayRoms AvilaNo ratings yet

- Making/#5dd031981409: 1. Don't DelayDocument17 pagesMaking/#5dd031981409: 1. Don't DelayRoms AvilaNo ratings yet

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Making/#5dd031981409: 1. Don't DelayDocument17 pagesMaking/#5dd031981409: 1. Don't DelayRoms AvilaNo ratings yet

- Making/#5dd031981409: 1. Don't DelayDocument17 pagesMaking/#5dd031981409: 1. Don't DelayRoms AvilaNo ratings yet

- Making/#5dd031981409: 1. Don't DelayDocument17 pagesMaking/#5dd031981409: 1. Don't DelayRoms AvilaNo ratings yet

- Making/#5dd031981409: 1. Don't DelayDocument17 pagesMaking/#5dd031981409: 1. Don't DelayRoms AvilaNo ratings yet

- Making/#5dd031981409: 1. Don't DelayDocument17 pagesMaking/#5dd031981409: 1. Don't DelayRoms AvilaNo ratings yet

- Making/#5dd031981409: 1. Don't DelayDocument17 pagesMaking/#5dd031981409: 1. Don't DelayRoms AvilaNo ratings yet

- Making/#5dd031981409: 1. Don't DelayDocument17 pagesMaking/#5dd031981409: 1. Don't DelayRoms AvilaNo ratings yet

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Making/#5dd031981409: 1. Don't DelayDocument17 pagesMaking/#5dd031981409: 1. Don't DelayRoms AvilaNo ratings yet

- Making/#5dd031981409: 1. Don't DelayDocument17 pagesMaking/#5dd031981409: 1. Don't DelayRoms AvilaNo ratings yet

- Cibse Lighting LevelsDocument3 pagesCibse Lighting LevelsmdeenkNo ratings yet

- Presentation 2Document35 pagesPresentation 2Ma. Elene MagdaraogNo ratings yet

- Architect / Contract Administrator's Instruction: Estimated Revised Contract PriceDocument6 pagesArchitect / Contract Administrator's Instruction: Estimated Revised Contract PriceAfiya PatersonNo ratings yet

- KB4-Business Assurance Ethics and Audit December 2018 - EnglishDocument10 pagesKB4-Business Assurance Ethics and Audit December 2018 - EnglishMashi RetrieverNo ratings yet

- Adverb18 Adjective To Adverb SentencesDocument2 pagesAdverb18 Adjective To Adverb SentencesjayedosNo ratings yet

- Admixtures For Concrete, Mortar and Grout ÐDocument12 pagesAdmixtures For Concrete, Mortar and Grout Ðhz135874No ratings yet

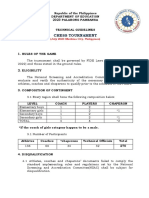

- CHESS TECHNICAL GUIDELINES FOR PALARO 2023 FinalDocument14 pagesCHESS TECHNICAL GUIDELINES FOR PALARO 2023 FinalKaren Joy Dela Torre100% (1)

- Bookkeeping PresentationDocument20 pagesBookkeeping Presentationrose gabonNo ratings yet

- IOPC Decision Letter 14 Dec 18Document5 pagesIOPC Decision Letter 14 Dec 18MiscellaneousNo ratings yet

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Management of TrustsDocument4 pagesManagement of Trustsnikhil jkcNo ratings yet

- Miske DocumentsDocument14 pagesMiske DocumentsHNN100% (1)

- Procedimentos Técnicos PDFDocument29 pagesProcedimentos Técnicos PDFMárcio Henrique Vieira AmaroNo ratings yet

- New Income Tax Provisions On TDS and TCS On GoodsDocument31 pagesNew Income Tax Provisions On TDS and TCS On Goodsऋषिपाल सिंहNo ratings yet

- FortiClient EMSDocument54 pagesFortiClient EMSada ymeriNo ratings yet

- Social Justice Society v. Atienza, JR CASE DIGESTDocument1 pageSocial Justice Society v. Atienza, JR CASE DIGESTJuris Poet100% (1)

- PAGCOR - Application Form For Gaming SiteDocument4 pagesPAGCOR - Application Form For Gaming SiteJovy JorgioNo ratings yet

- Buhay, Guinaban, and Simbajon - Thesis Chapters 1, 2 and 3Document78 pagesBuhay, Guinaban, and Simbajon - Thesis Chapters 1, 2 and 3pdawgg07No ratings yet

- Payroll in Tally Erp 9Document13 pagesPayroll in Tally Erp 9Deepak SolankiNo ratings yet

- 0607 WillisDocument360 pages0607 WillisMelissa Faria Santos100% (1)

- Sum09 Siena NewsDocument8 pagesSum09 Siena NewsSiena CollegeNo ratings yet

- Pranali Rane Appointment Letter - PranaliDocument7 pagesPranali Rane Appointment Letter - PranaliinboxvijuNo ratings yet

- HSN Table 12 10 22 Advisory NewDocument2 pagesHSN Table 12 10 22 Advisory NewAmanNo ratings yet

- Exception Report Document CodesDocument33 pagesException Report Document CodesForeclosure Fraud100% (1)

- Sample Balance SheetDocument22 pagesSample Balance SheetMuhammad MohsinNo ratings yet

- Introduction To The Study of RizalDocument2 pagesIntroduction To The Study of RizalCherry Mae Luchavez FloresNo ratings yet

- Samandar Bagh SP College Road, Srinagar: Order No: S14DSEK of 2022Document1 pageSamandar Bagh SP College Road, Srinagar: Order No: S14DSEK of 2022Headmasterghspandrathan GhspandrathanNo ratings yet

- Julius Caesar - Gallic War Bilingual - 10 First PagesDocument12 pagesJulius Caesar - Gallic War Bilingual - 10 First PagesTyrex: Psychedelics & Self-improvementNo ratings yet

- Passive Voice, Further PracticeDocument3 pagesPassive Voice, Further PracticeCasianNo ratings yet

- Stress and StrainDocument2 pagesStress and StrainbabeNo ratings yet

- On Rural America - Understanding Isn't The ProblemDocument8 pagesOn Rural America - Understanding Isn't The ProblemReaperXIXNo ratings yet