Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Myanmar's Endless Ethnic Quagmire - Bertil Lintner

Uploaded by

Pugh JuttaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Myanmar's Endless Ethnic Quagmire - Bertil Lintner

Uploaded by

Pugh JuttaCopyright:

Available Formats

Myanmar's endless ethnic quagmire

By Bertil Lintner Asia Times Online 8 March 2012 CHIANG MAI - A mass movement is spreading across Myanmar on a scale not seen since tens of thousands of Buddhist monks led anti-government demonstrations in 2007 and the massive nationwide pro-democracy uprising against the old military regime in 1988. This time the mobilizing force is a byelection contested by pro-democracy leader Aung San Suu Kyi and her National League for Democracy party to fill 48 seats in parliamentary bodies currently dominated by military aligned representatives. Wherever Suu Kyi appears on the campaign trail thousands of people of all ages have shown up to listen to her speeches, or just to line the roads and cheer along the routes of her motorcade. Big screen televisions, expensive sound systems and other sophisticated paraphernalia at her rallies are clear indications of support from sections of the private business community, which until recently had links almost exclusively with the traditional military establishment. Until a year ago many Western observers, including prominent European Union diplomats in Bangkok who cover Myanmar, asserted that Suu Kyi was a spent political force, that many young people didn't even know who she was because she had spent years under house arrest. Instead they felt that a new "Third Force" was emerging, one that challenged the supposed uncompromising stands of both Suu Kyi and the NLD, and the military-dominated government. The present mass movement shows clearly how wrong they were; most outsiders failed to understand that Suu Kyi was not only a political figure but, in the minds of many ordinary Myanmar citizens, a female bodhisattva who was going to deliver them from the evils of the country's military regime. At a recent rally in Mandalay, two teenage girls carried between them a huge red banner declaring that Suu Kyi was "a second god." Suu Kyi herself is opposed to her apotheosis but such representations promise to continue in the context of Myanmar's polarized political landscape. The existence of a viable "Third Force" may be a myth invented by donor agencies of Western countries and a host of mainly European private foundations eager to expand their enterprises and see a solution to Myanmar's decades-long political crisis. But there is a "third factor" to the equation which is bound to make Myanmar's journey towards democracy and peace extremely difficult: the unresolved ethnic issue. In the far north of the country, a bloody war between government forces and the Kachin Independence Army (KIA), an ethnic insurgent group fighting for autonomy within a federal union, shows no signs of abating despite several rounds of peace talks and mediation efforts by foreign reconciliation outfits. In other parts of the country, fragile ceasefire agreements between the government and various other rebel forces have maintained a semblance of peace. As Myanmar's history shows, ceasefires only freeze underlying problems and to date have not provided lasting solutions. There are still at least 50,000 men and women under arms across the country of ethnic resistance forces. To address these underlying problems, Suu Kyi has called for the convention of a second "Panglong Conference," in reference to an agreement that her father Aung San, who led Myanmar's fight for

freedom from colonial Britain, signed with representatives of the Shan, Kachin and Chin peoples at the small market town of Panglong on February 12, 1947. The agreement paved the way for a new federal constitution, which was adopted in September of that year and declared independence on January 4, 1948. Aung San was assassinated by a political rival in July 1947, but his Panglong agreement was honored in the constitution. Chapter Ten of that charter even granted the Shan and Karenni States the right to secede from the Union after a 10-year period of independence. Other ethnic states were not granted that right but the Panglong agreement stipulated that "full autonomy in internal administration for the Frontier Areas is accepted in principle." One of Myanmar's main ethnic groups, the Karen, did not sign the Panglong Agreement and instead resorted to armed struggle in 1949. Other, smaller ethnic groups such as the Karenni, Mon and Muslim mujahids also took up arms, as did the powerful Communist Party of Burma (CPB) and various groups of mutineers from the regular army who wanted to turn the country into a socialist republic. The civil war and political chaos led to the formation of a military caretaker government in 1958, which after less than two years in office handed power back to an elected civilian government. In March 1962, Myanmar's experiment with parliamentary democracy and federalism ended abruptly in a military coup. Then civilian prime minister U Nu had convened a seminar to discuss the future status of the ethnic frontier areas, not in order to dissolve the union, but rather to find ways forward by better defining and strengthening the country's federal structure. The new military government, led by General Ne Win, arrested all the participants in the seminar and abolished the 1947 constitution. With federalism abolished, Myanmar adopted a strictly centralized power structure with the military at its core. Very little has changed since the 1962 coup; the military has remained in power in various guises ever since. The 1974 constitution laid down provisions for seven "divisions" - where the majority Bama live - and seven ethnic states but there was no difference between those administrative entities. The new 2008 constitution grants the formation of local assemblies and the old divisions have been renamed "regions", but Myanmar is a Union only in name. The first chapter of the new constitution enables "the Defense Services to be able to participate in the National political leadership of the State." (sic) Colonial construct When Suu Kyi first broached a "Second Panglong" after her release from house arrest in November 2010, she received the backing of several ethnic leaders and organizations, among them the Shan Nationalities Democratic Party, the All Mon Regions Democracy Party, and the Rakhine (Arakan) Nationalities Development Party. At the same time, several pro-government bloggers branded her a "traitor" for resurrecting the autonomy granting agreement. Among them was a "Myanmar patriot" who wrote last November in a commentary on the exile-run Irrawaddy's website: "The incoming Parliament must make Panglong illegal! Anyone who promotes Panglong must be tried for treason, for endorsing the divide-and-rule of colonizers. NO way! We will fight all the way to stamp out traitors." Suu Kyi has since gone quiet on a "Second Panglong" but the problem with the new constitution and its centralized power structure remains a huge obstacle to achieving lasting peace in ethnic areas. Even if such a conference was convened, the procedure would be the reverse of what it was during the independence struggle of the 1940s. In January 1947, colonial authorities set up what was known as the Frontier Areas Committee of Enquiry, which held talks with representatives of various ethnic groups.

The Panglong Agreement was signed under colonial rule and half a year later an elected Constituent Assembly gave the country a new federal constitution under which independence was declared. Myanmar, then known as Burma, is a colonial creation that includes nationalities which historically had little or nothing to do with each other until British authority was established over the old Bama kingdom and a horseshoe-shaped ring of surrounding mountain ranges. Even today, there are remote tribal areas where the local people do not even know that they belong to a country called "Burma," or even less so "Myanmar." Myanmar's new military-drafted constitution is a non-federal one which ethnic representatives have been pressured to accept and lay down their arms in the name of national reconciliation. The constitution was ostensibly drawn up by a National Convention which met on and off over a 15 year period. Its delegates, however, were mostly handpicked by the then ruling military junta. Ethnic group representatives were clad up in their respective colorful national costumes for the spectacle and spent most of the time listening to endless speeches rather than discussing their regions' futures. A prominent Shan representative, Khun Htun Oo, was even charged with high treason and sentenced to 93 years imprisonment for criticizing procedures relating to the National Convention. He was released in January this year along with several hundred other political prisoners. None of the ceasefire agreements which the government has concluded with more than 20 big and small rebel groups since 1989 includes any political concessions by the central government. Rebels have in some instances been granted unofficial permission to retain control over their respective areas and been encouraged to engage in any kind of business to sustain themselves. The government's strategy seems to have hoped rebel groups would be more interested in making money than pressing demands for constitutional reform and political autonomy. That strategy is obviously not working, as the flare-up of hostilities in the northern Kachin State shows. On the other hand efforts by the various ethnic resistance forces to form a united front - or even to devise a common political platform - have also failed miserably. Most neutral observers familiar with Myanmar's ethnic issues would argue that the conflict is not only between the Bama and other nationalities but also between different minority ethnic groups. For instance, tensions have existed for centuries between the Kachin and the Shan, between the Shan and the Karen. A smaller group, the Pa-O, even took up arms in the early 1950s to fight against local Shan princes. In later years, Shan and Kachin rebels fought turf wars for control of areas in the country's northeast which have sizable Kachin populations but belong to Shan State. Even more recently, the Shan and Wa armies have fought bloody battles for control of areas adjacent to Thailand's border. Ethnic divisions It is also clear that the different backgrounds of Myanmar's multitude of ethnic groups, many with armed insurgent wings, will make it difficult to achieve a lasting solution to the problem. The insurgency among the Karen, who number at least 3.5 million and live in the Irrawaddy delta southwest of the old capital Yangon and in hills near the Thai border, is one of the longest lasting in the world. Many of them are Christian, mainly Baptist, and they have dominated most Karen rebel movements for more then six decades. The majority of the Karen, however, are actually Buddhist and fierce battles have been fought between the Democratic Karen Buddhist Army and the forces of the Christian-led Karen National Union.

The Shan are Buddhist and related to the Thais and the Laos, and traditionally have been ruled by feudal princes called saohpa, or "Lords of the Sky." They took up arms when the Panglong Agreement's 10-year-trial period was up in 1958 and it was clear that they would not be allowed to exercise their then constitutional right to secede from the union. The Kachin in the far north are almost entirely Christian, also mainly Baptist. Their rebellion broke out in 1961 when the then U Nu government tried to make Buddhism the state religion and at the same time had negotiated a border agreement with China which many Kachins disapproved. Shortly after the war broke out, Kachins, whose guerrilla warfare skills were recognized and utilized by Britain and the United States during the Japanese occupation in the 1940s, quickly seized control of most of their rugged hill country between China and India. The government has consistently failed to dislodge the Kachin from the geographical strongholds they established in the 1960s. The strongest and most powerful of Myanmar's ethnic armies, the drug-trafficking United Wa State Army (UWSA), has recently received scant attention. Its more than 30,000 men and women in arms are equipped with sophisticated weaponry obtained mainly in China, including modern automatic rifles, heavy machine-guns, 120mm mortars, and even man-portable, surface-to-air anti-aircraft missiles. The UWSA was born out of a mutiny among the Wa hilltribe rank-and-file of the CPB in 1989 where they drove the old, orthodox communist and mainly Bama leaders into exile in China. The CPB subsequently crumbled and was later divided into four regional ethnic armies of which the UWSA was the strongest. Currently the UWSA controls a huge area adjacent to the Chinese border, enclaves along the Thai border in the south, and most of the lucrative production areas of narcotics, opium, heroin and methamphetamines in the Myanmar sector of the so-called Golden Triangle. The Wa have never been controlled by any central government in Myanmar. They were headhunters well into modern times and few outsiders entered the area before it was taken over by the insurgent CPB in the early 1970s. Since the 1989 mutiny, the UWSA has independently administered the areas it controls. The pre-2010 elected government requested that all of those ethnic armies convert themselves into "Border Guard Forces" under command of the Myanmar Army. That proposal, however, had few takers; only some of the smallest former rebel groups agreed. For now, the plan seems to have been put on ice but it is unclear how the government aims to tackle the issue over the medium term. At the same time, there has been no deviation from the previous ceasefire strategy: stop fighting, engage in business, and forget any visions of a federal Myanmar. According to sources familiar with recent government-ethnic group negotiations, ethnic leaders have been told that "a discussion about federalism is not even on the table." On the other hand, there are few countries in the world that have a federal system based on ethnicity or along linguistic lines. India, the former Soviet Union and the former Yugoslavia are a few examples and show the perils ahead for such a potential model in Myanmar. India has survived and despite all the problems that country faces is perhaps the best model for Myanmar to adopt. The United States has geographical entities as member states of a union, Germany is based on ancient kingdoms and principalities, and even multinational Malaysia has a federal system based not on ethnicity - there are no Malay, Chinese and Indian states there - but on the old Malay sultanates. Whichever model Myanmar aims to follow, it cannot be done unless significant clauses in the present constitution are amended. Most of these, including those concerning state structure and ultimate military control over the decision-making process, cannot be considered without the approval of at least 75% of all parliamentarians in both the Upper and Lower Houses and would need to be enshrined through a national referendum. In practice, this makes any fundamental constitutional reform impossible.

Scrapping the 2008 constitution and drafting a new one based on some kind of federal concept is likely the only viable way ahead to resolving Myanmar's unresolved ethnic issue. Judging from the government's response to ethnic demands, that isn't likely to happen any time soon. Whatever the outcome of the present mass movement and the likelihood of some token NLD representation in parliament after the April 1 by-elections, Myanmar's ethnic quagmire will endure and the government's half-hearted calls for national reconciliation will remain unfulfilled. Bertil Lintner is a former correspondent with the Far Eastern Economic Review and author of several books on Burma/Myanmar, including Aung San Suu Kyi and Burma's Struggle for Democracy (Published in 2011). He is currently a writer with Asia-Pacific Media Services. (Copyright 2012 Asia Times Online (Holdings) Ltd. All rights reserved. Please contact us about sales, syndication and republishing.)

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Politics of Identity in Myanmar The Rohingya, Kachin & Wa Ethnic MinoritiesDocument41 pagesThe Politics of Identity in Myanmar The Rohingya, Kachin & Wa Ethnic Minoritieswashalinko100% (1)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Ethnic Minorities and ConflictsDocument4 pagesEthnic Minorities and ConflictsM Munour RashidNo ratings yet

- Leach, E. (1960) - The Frontiers of BurmaDocument21 pagesLeach, E. (1960) - The Frontiers of BurmaTan Zi HaoNo ratings yet

- Shan Ni GrammarDocument146 pagesShan Ni GrammarAlef Bet100% (2)

- Cost of Doing Business in Myanmar-Survey Report 2017Document199 pagesCost of Doing Business in Myanmar-Survey Report 2017THAN HAN100% (1)

- #NEPALQUAKE Foreigner - Nepal Police.Document6 pages#NEPALQUAKE Foreigner - Nepal Police.Pugh JuttaNo ratings yet

- Rcss/ssa Statement Ethnic Armed Conference Laiza 9.nov.2013 Burmese-EnglishDocument2 pagesRcss/ssa Statement Ethnic Armed Conference Laiza 9.nov.2013 Burmese-EnglishPugh JuttaNo ratings yet

- HARVARD:Crackdown LETPADAUNG COPPER MINING OCT.2015Document26 pagesHARVARD:Crackdown LETPADAUNG COPPER MINING OCT.2015Pugh JuttaNo ratings yet

- #Myanmar #Nationwide #Ceasefire #Agreement #Doc #EnglishDocument14 pages#Myanmar #Nationwide #Ceasefire #Agreement #Doc #EnglishPugh JuttaNo ratings yet

- UNODC Record High Methamphetamine Seizures in Southeast Asia 2013Document162 pagesUNODC Record High Methamphetamine Seizures in Southeast Asia 2013Anonymous S7Cq7ZDgPNo ratings yet

- Davenport McKesson Corporation Agreed To Provide Lobbying Services For The The Kingdom of Thailand Inside The United States CongressDocument4 pagesDavenport McKesson Corporation Agreed To Provide Lobbying Services For The The Kingdom of Thailand Inside The United States CongressPugh JuttaNo ratings yet

- Justice For Ko Par Gyi Aka Aung Kyaw NaingDocument4 pagesJustice For Ko Par Gyi Aka Aung Kyaw NaingPugh Jutta100% (1)

- MNHRC REPORT On Letpadaungtaung IncidentDocument11 pagesMNHRC REPORT On Letpadaungtaung IncidentPugh JuttaNo ratings yet

- HARVARD REPORT :myanmar Officials Implicated in War Crimes and Crimes Against HumanityDocument84 pagesHARVARD REPORT :myanmar Officials Implicated in War Crimes and Crimes Against HumanityPugh JuttaNo ratings yet

- Asia Foundation "National Public Perception Surveys of The Thai Electorate,"Document181 pagesAsia Foundation "National Public Perception Surveys of The Thai Electorate,"Pugh JuttaNo ratings yet

- ACHC"social Responsibility" Report Upstream Ayeyawady Confluence Basin Hydropower Co., LTD.Document60 pagesACHC"social Responsibility" Report Upstream Ayeyawady Confluence Basin Hydropower Co., LTD.Pugh JuttaNo ratings yet

- Myitkyina Joint Statement 2013 November 05.Document2 pagesMyitkyina Joint Statement 2013 November 05.Pugh JuttaNo ratings yet

- SOMKIAT SPEECH ENGLISH "Stop Thaksin Regime and Restart Thailand"Document14 pagesSOMKIAT SPEECH ENGLISH "Stop Thaksin Regime and Restart Thailand"Pugh JuttaNo ratings yet

- United Nations Office On Drugs and Crime. Opium Survey 2013Document100 pagesUnited Nations Office On Drugs and Crime. Opium Survey 2013Pugh JuttaNo ratings yet

- Modern Slavery :study of Labour Conditions in Yangon's Industrial ZonesDocument40 pagesModern Slavery :study of Labour Conditions in Yangon's Industrial ZonesPugh JuttaNo ratings yet

- Children For HireDocument56 pagesChildren For HirePugh JuttaNo ratings yet

- KNU and RCSS Joint Statement-October 26-English.Document2 pagesKNU and RCSS Joint Statement-October 26-English.Pugh JuttaNo ratings yet

- BURMA Economics-of-Peace-and-Conflict-report-EnglishDocument75 pagesBURMA Economics-of-Peace-and-Conflict-report-EnglishPugh JuttaNo ratings yet

- Brief in BumeseDocument6 pagesBrief in BumeseKo WinNo ratings yet

- KIO Government Agreement MyitkyinaDocument4 pagesKIO Government Agreement MyitkyinaPugh JuttaNo ratings yet

- Laiza Ethnic Armed Group Conference StatementDocument1 pageLaiza Ethnic Armed Group Conference StatementPugh JuttaNo ratings yet

- Poverty, Displacement and Local Governance in South East Burma/Myanmar-ENGLISHDocument44 pagesPoverty, Displacement and Local Governance in South East Burma/Myanmar-ENGLISHPugh JuttaNo ratings yet

- U Kyaw Tin UN Response by PR Myanmar Toreport of Mr. Tomas Ojea QuintanaDocument7 pagesU Kyaw Tin UN Response by PR Myanmar Toreport of Mr. Tomas Ojea QuintanaPugh JuttaNo ratings yet

- MON HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT: DisputedTerritory - ENGL.Document101 pagesMON HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT: DisputedTerritory - ENGL.Pugh JuttaNo ratings yet

- The Dark Side of Transition Violence Against Muslims in MyanmarDocument36 pagesThe Dark Side of Transition Violence Against Muslims in MyanmarPugh JuttaNo ratings yet

- Karen Refugee Committee Newsletter & Monthly Report, August 2013 (English, Karen, Burmese, Thai)Document21 pagesKaren Refugee Committee Newsletter & Monthly Report, August 2013 (English, Karen, Burmese, Thai)Pugh JuttaNo ratings yet

- SHWE GAS REPORT :DrawingTheLine ENGLISHDocument48 pagesSHWE GAS REPORT :DrawingTheLine ENGLISHPugh JuttaNo ratings yet

- TBBC 2013-6-Mth-Rpt-Jan-JunDocument130 pagesTBBC 2013-6-Mth-Rpt-Jan-JuntaisamyoneNo ratings yet

- Ceasefires Sans Peace Process in Myanmar: The Shan State Army, 1989-2011Document0 pagesCeasefires Sans Peace Process in Myanmar: The Shan State Army, 1989-2011rohingyabloggerNo ratings yet

- Taunggyi Trust Building Conference Statement - BurmeseDocument1 pageTaunggyi Trust Building Conference Statement - BurmesePugh JuttaNo ratings yet

- Burma's Environment: People, Problems, PoliciesDocument106 pagesBurma's Environment: People, Problems, PoliciesDag Hammarskjöld FoundationNo ratings yet

- Burman Troop Offensive War Against Kachin Postcolonial Nationalistic InterpretationDocument9 pagesBurman Troop Offensive War Against Kachin Postcolonial Nationalistic InterpretationPugh JuttaNo ratings yet

- Jade Full Report Second Run Online Hi Res q7urZIkDocument128 pagesJade Full Report Second Run Online Hi Res q7urZIkyaungchiNo ratings yet

- The North WarDocument132 pagesThe North WarkachincenterNo ratings yet

- Kachin Relief Action Network For IDP and Refugee (RANIR) - Information-Engl.Document6 pagesKachin Relief Action Network For IDP and Refugee (RANIR) - Information-Engl.Pugh JuttaNo ratings yet

- TSYO REPORT :pipeline - Nightmare-EnglishDocument53 pagesTSYO REPORT :pipeline - Nightmare-EnglishPugh JuttaNo ratings yet

- 201232621Document48 pages201232621The Myanmar TimesNo ratings yet

- The Kachin Conflict 2014Document54 pagesThe Kachin Conflict 2014AgZawNo ratings yet

- Torrential Monsoon Rains and Rising River Levels Have Caused FloodingDocument3 pagesTorrential Monsoon Rains and Rising River Levels Have Caused Floodingywon nay chi lwinNo ratings yet

- GNLM 2023-12-05Document15 pagesGNLM 2023-12-05Maung Aung MyoeNo ratings yet

- The Frontiers of BurmaDocument20 pagesThe Frontiers of BurmaChinLandInfoNo ratings yet

- Myanmar TimesDocument60 pagesMyanmar TimesMyat Zar GyiNo ratings yet

- 10 Jan 19 GNLMDocument15 pages10 Jan 19 GNLMmayunadiNo ratings yet

- LEACH, E. The Frontiers of Burma PDFDocument20 pagesLEACH, E. The Frontiers of Burma PDFWemersonFerreiraNo ratings yet

- 11 Jan 20 GNLMDocument15 pages11 Jan 20 GNLMPinlone AyeNo ratings yet

- 201333660Document56 pages201333660The Myanmar TimesNo ratings yet

- Deciphering Myanmar's Peace Process A Reference Guide 2015 (English Version)Document289 pagesDeciphering Myanmar's Peace Process A Reference Guide 2015 (English Version)Let's Save Myanmar100% (1)

- Kiik, Laur. 2016. Conspiracy, God's Plan, and National Emergency. Kachin Popular Analyses of The Ceasefire Era and Its Resource GrabsDocument31 pagesKiik, Laur. 2016. Conspiracy, God's Plan, and National Emergency. Kachin Popular Analyses of The Ceasefire Era and Its Resource GrabsMariaNo ratings yet

- Myanmar Mining Oct19Document32 pagesMyanmar Mining Oct19Saw Tun LynnNo ratings yet

- Kokang Troops Enter Kachin State From China SurreptitiouslyDocument2 pagesKokang Troops Enter Kachin State From China SurreptitiouslyPugh JuttaNo ratings yet

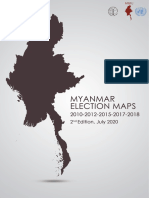

- Atlas of Myanmar Election Maps 2010-2018 IFES-MIMU Jul2020Document78 pagesAtlas of Myanmar Election Maps 2010-2018 IFES-MIMU Jul2020Waiphyo AungNo ratings yet

- War and Peace in the Borderlands of MyanmarDocument6 pagesWar and Peace in the Borderlands of MyanmarJaideep ChandaNo ratings yet

- Burma Female Army FINAL EnglishDocument2 pagesBurma Female Army FINAL EnglishKhinmg SoeNo ratings yet

- The Kachin Ethno-Nationalism Over Their Historical Sovereign Land Territories in Burma/MyanmarDocument26 pagesThe Kachin Ethno-Nationalism Over Their Historical Sovereign Land Territories in Burma/MyanmarSuri Lebo Paulinus100% (1)

- 201334661Document52 pages201334661The Myanmar TimesNo ratings yet