Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Conflict Dynamics

Uploaded by

Palash AhmadOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Conflict Dynamics

Uploaded by

Palash AhmadCopyright:

Available Formats

Conflict Dynamics After General Ziaur Rahman ("Zia") came to power through a military coup in 1975, the conflict

between the indigenous people and the Bengali government turned from a democratic struggle into a low-intensity armed conflict. Zia ordered full militarization of the CHT and simultaneously development of the "backward tribal" area. Next to road construction and telecommunication, settlement programs of the indigenous population in model villages (similar to the "strategic hamlets" erected during the war in Vietnam) were carried out. The fact that the CHT Development Board, set up by Zia, was headed by the military commander in charge of the CHT illustrates that these development programs were an instrument of counterinsurgency. From 1976 the CHT became an area under military occupation and a training ground for counterinsurgency. Many army officers received training in the United States and the United Kingdom. The security forces controlled the administration, as well as all development programs. The Indian government, worried about the military takeover in Bangladesh in 1975 (having lost its earlier influence over the Bangladesh government and fearing that the CHT might again become a hideout for insurgents from Northeast India), provided the PCJSS training and safe havens in the neighboring northeastern Indian state of Tripura. In late 1976, the Shanti Bahini carried out its first armed attack on a military outpost in the CHT. In the name of counterinsurgency against the Shanti Bahini, the Bangladesh security forces perpetrated massive human-rights violationsmassacres, killings, torture, rape, arson, forced relocation, forced marriages to Bengalis, and cultural and religious oppression of the indigenous people. In April 1979 the first of a series of massacres took place in Kanungopara, where reportedly 25 indigenous people were killed by the army and eighty houses were burnt down. In a second massacre on 25 March 1980, indigenous people in Kalampati/Kaukhali were forced to line up and then the army opened fire. Reports about the number of indigenous people killed in Kaukhali vary between 50 and 300. Young women were held by the army for days and raped. In the 1980s, 10 percent of the indigenous population fled to neighboring India, and others fled to isolated jungle areas. More than ten major massacres have taken place between 1979 and 1993 in which an estimated 1,200 to 2,000 indigenous people have been killed. These and subsequent massacres formed part of the counterinsurgency strategy to drive out the indigenous population and settle Bengalis on their land. One of the army generals reportedly said in 1977: "We want the land, not the people." Another main element in the counterinsurgency strategy was the settlement of some 400,000 landless Bengalis from the plains in the CHT between 1979 and 1985 under a secret government transmigration program. This dramatically changed the composition of the population: the percentage of Bengalis in the CHT rose from 26 percent in 1974 to 41 percent in 1981. Moreover, Bengalis illegally occupied indigenous people's land on a large scale. This further escalated the conflict. Land became one of the main sources of conflict between the indigenous people and Bengali settlers and the army. The PCJSS reacted to the militarization and Bengalization of the CHT by stepping up its armed actions. General Ershad who had come to power in yet another military coup in 1982, declared a general amnesty and a special fiveyear plan for the CHT after a split had occurred within the PCJSS in 1983 and Manobendra Larma, leader of the PCJSS, had been killed by the dissident faction. Manobendra's brother Jyotirindra Bodhipriya (Santu) Larma took over the leadership of the PCJSS. A large number of dissidents surrendered between 1983 and 1985. Repression and human-rights violations by the security forces in the CHT, however, continued as before. Some of the worst massacres took place in 1984 and 1986. Repressive measures restricted, for example, the freedom of movement and the selling and buying of essentials to prevent the delivery of supplies to the Shanti Bahini. The indigenous population was forcefully relocated in "model villages" (as a socalled rehabilitation measure to stop environmentally damaging jhum cultivation, but in fact to be better able to control them). Bengalis who could not be accommodated on the land that the fleeing and relocated indigenous people had left behind were settled in "cluster villages," usually next to a military camp where they served as a protective shield for the military. In defense of their rights and their land, the Shanti Bahini started carrying out attacks on Bengali settlers, trying to drive them out and prevent more settlers from coming to the CHT. These rehabilitation schemes, as well as road construction and afforestation programs, were largely funded by the Asian Development Bank. A few other donors, such as UNICEF and UNDP, also funded "development" programs in the CHT. The Swedish and Australian governments pulled out of road construction and afforestation programs in the CHT in the early 1980s after the repressive government policies seeped to the outside world and it became clear that these programs were not at all in the interest of the indigenous peoples. Partly due to international pressure, negotiations between the respective governments and the PCJSS have taken place since 1985 without, however, coming to any agreement. The main demands of the PCJSS were regional autonomy and constitutional recognition of the Jumma identity; withdrawal of the army from the CHT; and removal of the Bengali settlers from the CHT. Only in 1997 was a peace accord signed between the PCJSS and Sheikh Hasina's Awami League government that had won the national elections in 1996. The opposition parties led by the BNP and Bengali settlers opposed the accord as a sellout and campaigned fiercely against it. On totally different grounds, a section of the indigenous people who had earlier supported the PCJSS rejected the accord on the grounds that the main demands of the Jumma peoples had not been fulfilled and declared their intention to continue the struggle for autonomy by democratic means. They formed the United Peoples Democratic Front (UPDF) in December 1998.

The major part of the peace accord has yet to be implemented and so far the government elected in October 2001 has taken several measures that are in violation of the accord. For instance, Prime Minister Khaleda Zia has appointed herself as minister for CHT affairs and a Jumma representative only as deputy minister. The peace accord stipulates that the minister's post should be given to an indigenous representative from the CHT. Similarly, the government unilaterally appointed one of the CHT MPs, a Bengali settler and BNP member, as chairman of the CHT Development Board, bypassing the indigenous MP who should have been given preference as specified in the accord. BNP members have also been appointed unilaterally as chairmen of the three Hill District Councils and still no provisions have been made for elections of these district councils. Official Conflict Management From 1983 the International Labour Organization (ILO) criticized the Bangladesh government annually for inadequate reporting with regard to ILO Convention 107 on Indigenous and Tribal Populations to which Bangladesh is a signatory. The CHT issue was also raised annually in the UN Working Group on Indigenous Populations, and the Bangladesh government was questioned in the UN Human Rights Commission and the UN Sub-Commission on Prevention of Discrimination and Protection of Minorities. In 1987, the PCJSS demanded the deployment of a UN Peace-Keeping Force and implementation of its demands for withdrawal of the security forces and the Bengali settlers under the auspices of the UN. The successive governments, however, ignored this demand. No foreigners were allowed in the CHT and news coming out of the CHT was heavily censored. Dialogues between the PCJSS and the respective Bangladesh governments have taken place since 1985. After six dialogues between the PCJSS and the Ershad government in which the government remained inflexible to the demands of the indigenous people, the government coerced other indigenous leaders in 1989 into consent with the enactment of the three Hill District Councils, one for each of the three Hill Districts into which the CHT had been split up by then. In contrast to the rest of the country, the Hill District Councils were to be elected and the majority of the seats were designated for indigenous ("tribal") people. The government claimed to have thus given autonomy to the CHT. The PCJSS rejected the Hill District Councils outright. Their main arguments were that the councils had no constitutional basis and therefore could be repealed anytime; that they formalized and legitimized the illegal settlement of 400,000 Bengalis in the hills; and that only minor powers were given to the councils and the land rights of the indigenous people were not safeguarded. The Hill District Council elections in 1989 and its outcome were fully controlled by the Bangladesh army, refuting all claims of having given autonomy. In December 1990, Ershad was ousted by a mass movement that ended almost fifteen years of military rule in Bangladesh. In August 1992 the PCJSS unilaterally declared a cease-fire and from November 1992 several rounds of negotiations with the elected BNP government headed by Khaleda Zia were held, without any concrete results. Finally, in December 1997, negotiations with the Awami League government of Sheikh Hasina (daughter of the murdered Sheikh Mujibur Rahman), elected in 1996, culminated in the signing of a peace accord. Changes in the government in India were a factor in this as well. There were a few high-level meetings between the governments of Bangladesh and India, and India put pressure on the PCJSS to come to an agreement. The main points of the peace accord are: y Modification of the three Hill District Council Acts of 1989 and an indirectly elected Regional Council with a twothirds majority of indigenous members to coordinate and supervise the District Councils y Withdrawal of all security-force personnel to the six permanent cantonments in the CHT y Land to be placed under the jurisdiction of the Hill District Councils, and installation of a Land Commission to resolve all land disputes y Rehabilitation of surrendered PCJSS and Shanti Bahini members y Repatriation and rehabilitation of refugees from India and internally displaced persons The main weaknesses of the accord are: y No constitutional provision for the ethnic identity, nor for the councils, so these can be repealed any time y No deadline for the withdrawal of the security forces and no provisions for proper investigation of past and future human-rights violations y No timetable for implementation of the accord and no provision for independent monitoring of the peace process y The Land Commission has the near-impossible task of resolving the massive land disputes y The crucial issue of the Bengali settlers remains largely unresolved The PCJSS claims that during the negotiations a verbal agreement was made with the government to resettle the Bengali settlers outside the CHT. However, the government denies having made such an agreement. In 1996, the European Parliament had adopted an amendment to earmark part of the aid to Bangladesh "for the repatriation of Bengali settlers in the CHT back to the plains." Although the Bangladesh government had expressed its willingness to repatriate the Bengali settlers if funds were provided, according to the European Parliament, the government has so far failed to table any such proposal. The European Union and several other donor governments have made implementation of the peace accord conditional on funding development programs in the CHT. Four years after the signing of the accord, many of its provisions have yet to be implemented and there is disagreement

between the government and the PCJSS on several points. The slow implementation of the peace accord as well as the violent conflict between the PCJSS and the UPDF add to the continuing instability in the area. Multi Track Diplomacy A combination of historical factors, successive government policiesboth colonial and postcolonial administrationsand the particular development of "Bengali" nationalism2 that has finally led to the emergence of the eastern part of Pakistan as independent Bangladesh, have contributed to the development of the political and social collective identity of indigenous peoples in isolation from the mainstream Bengali society.3 This is not to say that both societies did not interact. But these interactions have been at best superficial; overwhelming portions of both societies remained unconcerned with each other's plight and existence. Because of the particular background to the situation of the indigenous peoples in the CHT, instances of multi-track diplomacy were few and far between during the pre-accord period. Nor was the tight, often heavy-handed, control of the government's administrative machinery over the region helpful in developing a congenial environment in this regard. But in order to put the role of the civil society in perspective, an outline of the role of civil society in the context of the CHT is in order. Civil Society Civil society in Bangladesh has a long and distinguished heritage. Communities and associations have continued to play a significant part in the sociopolitical life of the territory from the distant past. Even during the British colonial time these entities articulated the feelings and demands of the society at large and made significant direct and indirect contributions to shaping official policy. Civil society continued to play a strong role during the period when Bangladesh was part of Pakistan and made important contributions to the flowering of the movement for autonomy and eventually independence of the territory. However, at this stage all the efforts of the civil society were concentrated on the autonomy movement of the "Bengali" people and civilizationa logical consequence to distinguishing it from the West Pakistanidominated venture of building Pakistan on an Islamic religious model. But this ethnocentric effort of the predominant Bengali civil society hardly left any room for accommodating the aspirations of their ethnic minority brethren. It is, then, not surprising to find, immediately after the independence of Bangladesh, the failure of the newborn nation to take account of the demands of the CHT MP, Manabendra Narayan Larma, for a separate autonomous status for his region by providing constitutional safeguards for ensuring distinct identities of its indigenous ethnic minority inhabitants. One cannot overlook the irony in the fact that the same people who gained independence in the name of cultural self-determination failed to respond to the aspirations of people in a similar situation in its own territory. Although the events of 1975 and the subsequent intrusion of the military into the politics of postliberation Bangladesh seriously disrupted the process of growth and development of civil society, it continued to maintain a steady existence. Despite obstacles, sociocultural, human-rights, civic, and community organizations participated consistently in the struggle for restoration and strengthening of democracy in the country during the mid-1980s and mid-1990s. However, this important component of the Bangladeshi society remained mostly silent or ignored the events of militarization and military atrocities in the Chittagong Hill Tracts. A possible explanation might be its ethnocentric origins (these civil-society organizations are mostly composed of and led by Bengalis and have little or no participation from their indigenous counterparts) and also its preoccupation with the struggle for restoring democracy in the country following the tragic events of 1975, which was considered more important.4 The tight military control and brutal repression did not allow either the intervention of outside organizationsnational or internationalin the conflicts of the Chittagong Hill Tracts or to the growth of any such indigenous organizations. The few organizations of the latter category were built up either by the military or with direct support from them, as a result of which none of these organizations could claim any legitimacy in the eyes of the indigenous inhabitants of the region. Another reason for the silence of civil-society organizations on the CHT conflict may have been the paucity of factual information because of the situations of armed conflict and violence. There were, however, a few notable examples where civil society played a bold and courageous role. One such example is the series of events immediately following the Kalampati massacre in 1980. The subsequent inquiry by a commission, comprised of the then member of parliament from the CHT along with other prominent representatives of civil society, disclosed to the outside world the gruesome, cold-blooded killing of innocent indigenous civilians, perpetrated jointly by the Bangladesh army and the local Bengali settlers. From the late 1980s and during the 1990s, civil-rights organizations and activists started to become more and more vocal and raised their concerns on the prevailing situation in the Chittagong Hill Tracts and the violation of human rights of its indigenous inhabitants. Besides, the individual activists who worked to strengthen this trend included prominent personalities such as poet Shamsur Rahman and political personality Rashed Khan Menon of the left-wing party alliance. From the mid1990s onward, the involvement of the civil society became even stronger, and with the signing of the peace accord in 1997 this momentum could only grow as the NGO sector continues to play a proactive role. In particular, the National Committee for the Protection of Fundamental Rights in the CHT has, since the early 1990s, supported the Jumma peoples' rights and

demands and continues to do so. Since the return to parliamentary democracy in 1991, more information about the past and present situation in the CHT has become available, although the issue of indigenous peoples' rights, in particular in the CHT, remains sensitive. From 1989, Jumma people organized themselves in three organizations: first, the Hill Students' Council, and a few years later the Hill People's Council and Hill Women's Federation. They campaigned for the PCJSS demands and the Jumma people's rights from a democratic platform, withstanding severe repression. They formed alliances with progressive Bengali forces. The Hill Women's Federation addressed in particular the oppressionrape, sexual violence, forced marriages, etc.of their women in the armed conflict, as well as the issue of equality and respect for women within their own societies. In the year following the peace accord, the Hill Students' Council, Hill People's Council, and Hill Women's Federation split into two factions, one supporting the accord and one rejecting it. The latter formed their own political party in December 1998, the United Peoples Democratic Front (UPDF). The UPDF has met with severe repression and there is continuing rivalry between the PCJSS and the UPDF, regularly culminating in violent confrontations. Mediation attempts by Jumma elders between the two groups have so far failed to stop the attacks, let alone bring about an agreement. From the early 1980s onward, several international NGOs, such as the Anti-Slavery Society, Survival International, the International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs, the Minority Rights Group, and Amnesty International, have brought out reports on the human-rights violations in the CHT. In 1990 the international Chittagong Hill Tracts Commission carried out an independent investigation in the refugee camps in Tripura and also managed to get into the CHT. The commission reported extensively on the background and development of the conflict and the massive human-rights violations. International aid agencies and donor governments, alarmed by the reports, started questioning the Bangladesh government and gradually international pressure was put on Bangladesh to come to a political solution of the conflict. Because of the ongoing conflicts very few development organizations were working in the CHT area before the accord of 1997. However, in the postaccord era many big national NGOs5 have expanded their activities and services in the region. Further, a number of locally inspired NGOs have come into beingfounded mostly by the local indigenous inhabitants. At the moment, there are fifty-two registered NGOs at work in the CHT. If nonregistered NGOs are considered, the number may be as high as three hundred, as estimated by the Asian Development Bank (ADB). The bulk of these NGOs focus on health, education, water, and sanitation, with microcredit activities mostly done by the big national NGOs with little or no participation by the local indigenous NGOs. Apart from this, NGOs are intervening in diverse areas such as agriculture, horticulture, afforestation, fisheries, poultry farms, microcredit, education, women in development, income generation, the environment, and training and development in general. Reflection on NGO Initiatives Unlike all other regions of Bangladesh, the armed conflicts of the past decades have severely restricted the activities of NGOs in the CHT. As a result, while there are a good number of NGOs with divergent interests working in the region, most of them are just evolving and gaining experience. This is particularly true of the local indigenous NGOs who have been able to start their activities only during the last couple of years. This fact is all the more important given the need for gigantic reconstruction and other developmental work in the region. The involvement of the NGOsparticularly the local indigenous NGOswill be crucial if development projects are to meaningfully address the frustrations and aspirations of the indigenous peoples. Moreover, many of the indigenous peoples feel that their frustrations, problems, and aspirations cannot be truly addressed by organizations from the outside because of the particularity of the problemsethnic, social, cultural, geographic, religious, etc. Such worries have already been raised on several occasions.6 It has also been indicated that the bureaucratic and administrative rigidity of the large national NGOs7 may not be appropriate to the particularity of the CHT peoples. So, unless the genuine participation of the indigenous peoples and their representative organizations can be ensured in any development process, their aspirations are likely to remain unfulfilled. The local indigenous NGOs are thought to be representativespecifically for the developmental activities. However, such a view of the local indigenous NGOs also puts them in a difficult position with respect to the government, as has been witnessed in the accusations and counteraccusations in MarchApril 2001 between the government and indigenous NGO leaders in the national media. The government accused some local indigenous NGOs8 of working against the stipulations of the peace accord and involvement in activities subversive to the state of Bangladesh. The NGOs concerned vehemently denied these accusations and protested against government measures to have them supervised by the security agencies. They described these measures as denying the right to development and universally recognized fundamental human rights of the indigenous peoples. But despite this tussle between the government and indigenous NGOs, the government seems to have accepted the principle of "particularity" regarding the activities of NGOs in the CHT region. As per the stipulation of the peace accord, the former Special Affairs Division has been converted to a new, full-fledged ministry with the name of the Chittagong Hill Tracts Affairs Ministry, to be headed by an indigenous representatives of the CHT. This ministry is vested with power to look after the activities of the NGOs in the region. In the long run, much will depend on how much the local indigenous NGOs can grow. Despite their recent existence and small size, it is rightly argued that they represent many of the genuine concerns, voice, and aspirations of the indigenous peoples of the CHTespecially in matters related to development activities. Another point to be observed is whether the

development of the local indigenous NGOs in the CHT could follow the path of their predecessors at the national level and, starting with small-scale relief and rehabilitation operations, grow into larger service delivery and/or social-mobilization organizations, fully integrating themselves with the civil society of the countryin fact, even becoming one of the dominant voices of the civil society. In a country such as Bangladesh, ridden with political schisms and intolerance, a robust and burgeoning civil society may be one of the best guarantees for ensuring its often-threatened democracy and the civil and political rights of its peoples. Similarly, in a region that has been bogged down in a bloody civil war for the last two decades, a robust and vibrant NGO sector capable of bridging between the civil society of the country and the concerns and aspirations of the peoples of the region is highly desirable. In a country that often becomes diametrically divided along lines of political affiliation, voices of moderation are one of the most precious things to be nurtured. And most would agree that it is the failure to listen to the voice of moderation of Manabendra Larmarecognition of the specific rights of the indigenous peoples of the CHT within the constitutional framework of the countrythat led to the bloodshed of the past decades. Now, in the aftermath of the peace accord, it seems vital to support the indigenous NGOs of the CHT to follow this line of moderation, to continue in representing certain concerns and aspirations of the people of the region within the larger fabric of the nation. Prospects With the signing of the accord in 1997, two strategic developments for the betterthe surrender of arms and the return of refugees and their rehabilitationhave taken place. Although it should be noted that many refugees are still not properly rehabilitated, many have not yet had their land returned and some are still living in transit camps. When the accord was signed, it was widely hoped that it would usher in a new age for the people of the region with a greater pace of socioeconomic development. The accord, by and large, has been accepted by the peoples of the region and by the donor community as wellthough one section of the indigenous people has explicitly rejected the accord and has formed the United Peoples' Democratic Front, which continues the demand for autonomy (within the state of Bangladesh). Accordingly, a good number of representatives from donor country/agencies and multilateral development agencies have visited the region, and some of these agencies have started to disburse funds for different development projects. Alongside these initiatives, a number of NGOsboth local and nationalare also undertaking development programs. Prospects for peace in the CHT have at least become brighter. However, it should be noted that the government and the PCJSS has already fallen apart politically. The PCJSS claims that most of the provisions of the accord (to the extent of 98 percent) remain unimplemented. The government, in turn, counters that a similar portion of the accord has already been implemented. The PCJSS further claims that in addition to the stipulations agreed upon in the peace accord, there has been an unwritten agreement between the government and PCJSS on several other matters, most notably on relocation of the settlers. The PCJSS is also extremely critical of the government's failure to withdraw as many as five hundred temporary army camps and of the continuation of the de facto army rule in the CHT. While the accord requires that any settlement or acquisition of land should be done with the consent of the District Council, the PCJSS complains that the government has acquired huge tracts of land for setting up a new army training ground and an air force base in Bandarban district, violating the existing laws and most importantly, the spirit of the peace accord. The government has also expanded the Reserve Forest and is planning to declare more land as Reserve Forest. But the main point of disagreement between the two parties is on the relocation of the Bengali settlers and subsequently the preparation of a voters' list for the region, based on the stipulation agreed in the peace accord. The alleged noncooperation by the government on the latter issue has even led the PCJSS to boycott the last national parliamentary elections. As part of the stipulation of the peace accord, the government has formed a Task Force on Rehabilitation of Returnee Refugees and Internally Displaced Persons, chaired by the MP for Rangamati in 1998. But almost immediately after the formation of this task force, its interventions led to controversy and disagreement because it also wanted to declare a large number of Bengali settlers as internally displaced persons and provide for their rehabilitation. As a result, the PCJSS, one of its key members, has boycotted the meetings of the task force since its last session eighteen months ago. Similarly, a land commission is supposed to start to work on settling land disputes in the region. But although it has been formally declared, nearly four years after the signing of the peace accord it has yet to begin work. With the change of power in the government following the last parliamentary elections in October 2001, the initiatives of the new government of the BNP for tackling these impending issues should be noted. As per the provisions of the peace accord, a ministry of CHT affairs and a regional council have been constituted. While the former is coordinating and supervising the overall development and administrative activities of the region, the latter has been marginalized, allegedly due to the unwillingness of the government, although according to the peace accord the regional council is supposed to play a crucial role in the development and administrative activities of the region. Another worrying point for the people of the region in the post-accord period is the general deterioration in law and order, aggravated by the division among the indigenous peoplethe rivalry between the PCJSS and the UPDF. The power vacuum created by the surrender of arms by the PCJSS and consequently their return to normal life has not been filled either by the law-and-order enforcement agencies or by any local representative bodies, such as the regional council or the local district councils. As a result, extortion and rent-seeking activities have multiplied. Many of these problems owe their origins to the slow implementation of the provisions of the accord.

In light of this situation, it might be asked, what possibility is there that the situation will relapse into conflict? The accord certainly envisages a political process that has been, by and large, accepted by the public. Second, it will be difficult for the PCJSS and Shanti Bahini leaderships simply to go back to the jungle and resume insurgency. So instead, one should ask how the situation in the CHT might evolve in the near future. If a power vacuum is not properly filled, the risk of anarchy always remains potent, and that is exactly what is happening at present in the CHT. The present law-and-order situation and the activities of the UPDF9 may be seen as symptoms of a "residual insurgency" from which the region is suffering at present. If the root causes of the conflict are not properly addressed, any fault-line conflicts always have the potential to rekindle at any moment. Furthermore, one should keep in mind that, geopolitically, the CHT straddles an active crossborder insurgency area. Hence, continuing frustration may provide incentives for regrouping and the resumption of violence, perhaps not necessarily with insurgency but with other equally disruptive forms for the society as a whole. Recommendations From the point of view of conflict prevention, the key concern is to undertake measures so that conflict is not resumed. Now that the Peace Accord of 1997 is an established fact, the key recommendation will be to continue implementation of the accord without setbacks. Key issues creating the major stumbling block between the government and the PCJSS are settlement of land disputes, rehabilitation of the remaining refugees, and the voter list. The government must show deep commitment and take bold steps in resolving these problems. One recommendation is for the government to show political commitment to the implementation process. For this, the National Implementation Committee should meet and there should not be any lack of visible interest on the part of the government to implement the accord. Further, the government must initiate the appropriate relocation of the Bengali settlers who had been rehabilitated there by the government as counterinsurgency measures in the late 1970s and 1980s. Unless, the issue of the settlers can be definitively settled, the seeds for further discontent, and thus violence, will always remain potent among the indigenous people of the region. The reported news of assurance from several donor agencies for funding initiatives for relocation of Bengali settlers elsewhere should be seen as a great facilitating process. Over the past two years, the PCJSS leadership seems to have become disillusioned with the government and it seems that national electoral politics are the main reason. The government's political priorities seem to get preference over its commitment to the accord, leading to alienation and lack of confidence. The PCJSS, with which the government signed the accord, has become the ruling party's opponent in the context of national politics. The victory of the BNP-led coalition in the last election and the subsequent formation of a new government by this coalition, may lead to the revision of government policy on the CHT, as it declared in its electoral manifesto. Such revision of policies must not abrogate the provisions and hamper the spirit of the peace accord. Add to this the lack of progress on two other vital issuesthe land commission, and army camps and virtual army ruleand the situation in the CHT has the potential to degenerate further. One of the most pertinent answers to redress the above discontent would be to institute the local democratic process through elections to the district councils and the regional council. The democratic process will mitigate a lot of these grievances. Concomitant to the elections in the district and regional councils, the government must initiate a rapid handing over of powers to these institutions, as stipulated in the provisions of the peace accord. The existence of a crippled regional council and district councils might provoke more violence in the long run than no such councils at all. The provisions of the accord with regard to withdrawal of army camps should also be implemented. The visibility of the army should be reduced. The land commission should be set in operation. Settling the land disputes is going to be a very complicated and lengthy process. But initiation of the land commission will go a long way in neutralizing some of the opposition to the accord. Wherever any injustice has taken place, it should be mitigated with boldness. There should also be a policy of encouraging the activities of the local indigenous NGOs in the area, as long as their areas of intervention remain within the purview of the provisions of the peace accord. While this may outrage the hawks concerned with the security and sovereignty of the nation, in the long run such an approach might prove far more effective in circumscribing and venting the anger and frustrations of the indigenous peoples in a more constructive and productive manner. Such a policy must also target regular meetings and exchanges with their peers at the national level and the civil society at large. The accord signified an important and bold step toward conflict resolution through negotiation and peaceful means. It also demonstrated that the political process should be allowed to function in the CHT. Such a process will ultimately also be beneficial in cultivating mutual tolerance and respect between the different factions among the indigenous people. Finally, the sooner the elected district councils and the regional council start functioning and the provisions of the peace accord are fully implemented, the quicker will be the mitigation of many of the existing problems and the elimination of the causes of potential conflict. We would also recommend that the indigenous people stop the infighting between the PCJSS and UPDF, which has already led to some forty deaths and several kidnappings on both sides after the accord.

You might also like

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5795)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Newspaper Report Adapted With Exercises Reading Comprehension Exercises 60927Document2 pagesNewspaper Report Adapted With Exercises Reading Comprehension Exercises 60927GabrielleNo ratings yet

- UavDocument32 pagesUavnejatkaracaNo ratings yet

- Ebay International Standard Delivery Country Code ListDocument1 pageEbay International Standard Delivery Country Code ListDharmavijayyaNo ratings yet

- H225M-Brochure 2020Document12 pagesH225M-Brochure 2020Rodrigo Arantes100% (1)

- Fleet BandDocument11 pagesFleet BandAdamEpler100% (1)

- Battle of BuxarDocument3 pagesBattle of BuxarKeshav JhaNo ratings yet

- Tau Farsight Enclaves 1500ptsDocument14 pagesTau Farsight Enclaves 1500ptsOzcan Adnan KuknerNo ratings yet

- Dennis Rieke BioDocument3 pagesDennis Rieke Bioapi-304886548No ratings yet

- Military & Pyrotechnics & Rocketry - Scribd CollectionDocument19 pagesMilitary & Pyrotechnics & Rocketry - Scribd CollectionRadu100% (1)

- Army Ideas For Excellence Program (Aiep) Proposal: 1. Suggester InformationDocument2 pagesArmy Ideas For Excellence Program (Aiep) Proposal: 1. Suggester InformationKenneth CravensNo ratings yet

- Historyofwarinso 02 MauruoftDocument732 pagesHistoryofwarinso 02 MauruoftMark MooreNo ratings yet

- CAVITE MUTINY Different AccountsDocument30 pagesCAVITE MUTINY Different AccountsJohanna Chloe PaneloNo ratings yet

- MP Avt 108 38Document16 pagesMP Avt 108 38Junaid YusfzaiNo ratings yet

- Auftragstaktik We Can't Get There From HereDocument57 pagesAuftragstaktik We Can't Get There From HereЕфим Казаков100% (2)

- ProMob 8p Folder Lowres WebDocument6 pagesProMob 8p Folder Lowres WebBernard ReyNo ratings yet

- Vulcan: Journal of The Social History of Military TechnologyDocument1 pageVulcan: Journal of The Social History of Military TechnologyPeter Konieczny100% (3)

- Henry Big Boy - H006 Series RiflesDocument11 pagesHenry Big Boy - H006 Series RiflesMaster Chief100% (1)

- GD - January 2016Document140 pagesGD - January 2016Dennis Shongi100% (1)

- 14dec Lowery EdwardDocument140 pages14dec Lowery EdwardkarakogluNo ratings yet

- Appendix (Safe Diving Distances From Transmitting Sonar)Document42 pagesAppendix (Safe Diving Distances From Transmitting Sonar)Han TunNo ratings yet

- Inglês - Enunciado - 10cla - 1 Ép 2012 PDFDocument2 pagesInglês - Enunciado - 10cla - 1 Ép 2012 PDFLiangYangNo ratings yet

- Secret: Brgy Erenas, San Jorge, SamarDocument2 pagesSecret: Brgy Erenas, San Jorge, SamarFirstSamar PmfcNo ratings yet

- Downtown Hotel Feasibility StudyDocument84 pagesDowntown Hotel Feasibility StudyMohammad Ahmad Ayasrah100% (2)

- FKSM 71-8 ACR Dec 08Document61 pagesFKSM 71-8 ACR Dec 08Big_Juju100% (2)

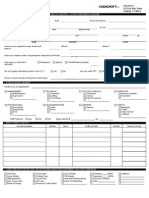

- Application For Employment: Ashcroft Inc. 250 East Main Street Stratford, CT 06614Document5 pagesApplication For Employment: Ashcroft Inc. 250 East Main Street Stratford, CT 06614raffaraffa123No ratings yet

- Fe 6 SpeechDocument588 pagesFe 6 SpeechLuiz FalcãoNo ratings yet

- Mco 10110.49Document25 pagesMco 10110.49taylorNo ratings yet

- Practice Test 6Document6 pagesPractice Test 6Crystal Phoenix100% (1)

- CAP Regulation 39-3 - 02/22/2019Document41 pagesCAP Regulation 39-3 - 02/22/2019Bob BaldwinNo ratings yet

- 1976 From Khyber To Oxus - Study in Imperial Expansion by Chakravarty S PDFDocument294 pages1976 From Khyber To Oxus - Study in Imperial Expansion by Chakravarty S PDFBilal AfridiNo ratings yet