Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Tetanus

Uploaded by

Bengia Meling LindaOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Tetanus

Uploaded by

Bengia Meling LindaCopyright:

Available Formats

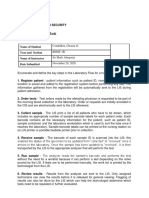

Management of Tetanus on the ICU Dr John Griffiths DICM MRCP FRCA MA CriticalCareUK Editor

Focus on tetanus Tetanus is characterised clinically by rigidity, muscle spasms and autonomic instability. It has become a rare disease in developed countries following the introduction of widespread immunisation programmes. Approximately 10 cases are reported each year in the UK. Those at high risk of developing tetanus are immigrants, the elderly and intravenous drug abusers. Modern intensive care management has achieved a dramatic reduction in mortality. In one series, all-age mortality from tetanus fell from 44% to 15% after the introduction of an ICU. However, mortality remains high in patients over 60 years of age, and can exceed 50%. In the developing world, tetanus remains endemic.

Focus on prevention of tetanus The immunisation programme in the UK was introduced in 1961, and assigns a total of five injections of adsorbed tetanus toxoid to every child. Every person who has received this full course is regarded as having life-long immunity against tetanus. A course of three injections in adulthood provides 5 to 10 years protection, two injections only 6 months protection. Patients with open wounds should be given a dose of adsorbed tetanus toxoid if not fully immunised or if the immunisation status is unclear. This initial dose should be followed by further doses (at 4-week intervals) to complete a course of 3 injections. Wounds that are infected or necrotic, or contaminated by soil or manure are especially susceptible to tetanus. In these high-risk cases, tetanus immunoglobulin (250 to 500 units intramuscularly) should be administered in addition to tetanus toxoid. Contaminated wounds need to be cleaned thoroughly. Necrotic or infected areas should be surgically debrided.

Focus on the management of tetanus The lack of randomised controlled trials assessing treatment options for tetanus limits the evidence-based approach to its management. One key aspect of treatment is the provision of adequate sedation. This is commonly provided by benzodiazepines (often in high doses), often in combination with opiates. Additional benefit may be provided by anticonvulsants, (particularly phenobarbitone), chlorpromazine, clonidine or dantrolene. If the control of rigidity and muscle spasms is inadequate, then neuromuscular blocking agents and mechanical ventilation are often necessary. Recently, remifentanil has been used successfully to control muscle spasms refractory to other recognised treatments. If further control of sympathetic overactivity is required, then beta-adrenergic blocking agents are useful adjuncts. However, the use of these drugs in tetanus has been associated with profound bradycardia, hypotension and sudden death.

Magnesium sulphate may offer another treatment modality to reduce spasms, rigidity and autonomic instability. Magnesium acts as a presynaptic neuromuscular blocker and vasodilator, reduces catecholamine release and catecholamine receptor responsiveness, and antagonises the effects of calcium in the myocardium. Magnesium also possesses anticonvulsant properties. The largest case series of the management of patients with tetanus comes from Sri Lanka. In this series of 40 patients, the tetanic spasms and muscle rigidity were controlled with an infusion of magnesium as the sole agent. This required an average plasma magnesium concentration of 2-4 mmol/L. Interestingly, control of spasms was not followed by hypertension or tachycardia. In six patients, hypotension (systolic blood pressure below 70 mmHg) and bradycardia (heart rate below 40/min) occurred, which was reversed in four patients by reducing the infusion rate. In this case series, all patients underwent early tracheostomy initially to facilitate endotracheal suctioning. However, subsequent respiratory complications or magnesium-related muscle paralysis meant that 30% of patients under 60 years of age and 60% over 60 years eventually required mechanical ventilation. A reduced level of consciousness was found in four patients with plasma magnesium concentrations above 3.5 mmol/L. All patients developed hypocalcaemia, which normalised after discontinuation of magnesium. The authors of this case series recommend magnesium as a first-line treatment for severe tetanus. However, potential side effects of magnesium, especially respiratory muscle paralysis and cardiovascular depression, remain a matter of concern.

You might also like

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Care of Clients With Maladaptive Patterns of BehaviorDocument136 pagesCare of Clients With Maladaptive Patterns of BehaviorAyaBasilio83% (12)

- Emphysema & EmpyemaDocument26 pagesEmphysema & EmpyemaManpreet Toor80% (5)

- Drug KenalogDocument1 pageDrug KenalogSrkocherNo ratings yet

- Hyperemesis GravidarumDocument5 pagesHyperemesis GravidarumGladys Ocampo100% (5)

- Neuro AssessmentDocument13 pagesNeuro Assessmentyassyrn100% (2)

- Radiology in UrologyDocument39 pagesRadiology in UrologyUgan SinghNo ratings yet

- Biologic WidthDocument44 pagesBiologic WidthRohit Rai100% (2)

- Dental Case Sheet Corrcted / Orthodontic Courses by Indian Dental AcademyDocument8 pagesDental Case Sheet Corrcted / Orthodontic Courses by Indian Dental Academyindian dental academyNo ratings yet

- Treatment of Thalassemia: Nadirah Rasyid Ridha Dasril DaudDocument30 pagesTreatment of Thalassemia: Nadirah Rasyid Ridha Dasril DaudIfah Inayah D'zatrichaNo ratings yet

- Spontaneous Intracerebral Hemorrhage: Pathogenesis, Clinical Features, and DiagnosisDocument25 pagesSpontaneous Intracerebral Hemorrhage: Pathogenesis, Clinical Features, and DiagnosisBryan Tam ArevaloNo ratings yet

- Hudson RCI Product CatalogDocument89 pagesHudson RCI Product Catalogmartyf777100% (1)

- Buzzwords For ExamsDocument16 pagesBuzzwords For ExamsU Rock BhalraamNo ratings yet

- Silberstein 2015Document17 pagesSilberstein 2015chrisantyNo ratings yet

- Vertebrobasilar Stroke - Overview of Vertebrobasilar Stroke, Anatomy of The Vertebral and Basilar Arteries, Pathophysiology of Vertebrobasilar StrokeDocument26 pagesVertebrobasilar Stroke - Overview of Vertebrobasilar Stroke, Anatomy of The Vertebral and Basilar Arteries, Pathophysiology of Vertebrobasilar StrokeLuis SilvaNo ratings yet

- Osteoporosis: Causes, Incidence, and Risk FactorsDocument5 pagesOsteoporosis: Causes, Incidence, and Risk FactorsEmeka JusticeNo ratings yet

- Extrapiramidal Symptom Rating Scale PDFDocument11 pagesExtrapiramidal Symptom Rating Scale PDFsisca satyaNo ratings yet

- Inverted Nipple PaperDocument7 pagesInverted Nipple PaperFarisah Dewi Batari EmsilNo ratings yet

- Congenital Malformations of The Genital Tract andDocument19 pagesCongenital Malformations of The Genital Tract andabhinay_1712100% (1)

- Doctor'S Order and Progress NotesDocument3 pagesDoctor'S Order and Progress NotesDienizs LabiniNo ratings yet

- Mammography LeafletDocument15 pagesMammography LeafletWidya Surya AvantiNo ratings yet

- Short WaveDocument31 pagesShort WaveDharmesh MaheshwariNo ratings yet

- Glove SOP For Glove by DR Mohamed RifasDocument3 pagesGlove SOP For Glove by DR Mohamed RifasDrMohamed RifasNo ratings yet

- Lesson 14 - Individual TaskDocument2 pagesLesson 14 - Individual TaskChristine CondrillonNo ratings yet

- Aree Di LindauerDocument4 pagesAree Di LindauerGianluca PinzarroneNo ratings yet

- Group 10 - Time & Stress Management NotesDocument6 pagesGroup 10 - Time & Stress Management NotesMimi Lizada BhattiNo ratings yet

- Who en enDocument307 pagesWho en enAafreen ShaikhNo ratings yet

- Update Therapeutic CommunicationDocument11 pagesUpdate Therapeutic CommunicationSupriyatin AjjaNo ratings yet

- WelchAllyn Propaq Encore Vital Signs Monitor - Reference GuideDocument178 pagesWelchAllyn Propaq Encore Vital Signs Monitor - Reference GuideSergio PérezNo ratings yet

- Aurora 4Document8 pagesAurora 4Jesus PerezNo ratings yet

- Medical Tourism IndiaDocument3 pagesMedical Tourism IndiafriendsofindiaNo ratings yet