Professional Documents

Culture Documents

CSR

Uploaded by

5415763Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

CSR

Uploaded by

5415763Copyright:

Available Formats

A publication of Directors & Boards magazine

Exclusive

New Research

on CSR

Boardroom Briefing

With the support of

W i n t e r 2 0 0 6

w w w. d i r e c t o r s a n d b o a r d s . c o m

We help our

cl i e ntsb u i ld the best

LE A DE R S H I P

teams inthe wo rld .

D

rawing upon a 50-year legacy, we

focus on quality service and build

strong leadership teams through our

relationships with cl i ents and indivi duals

worldwide. With our experience, we excel in

the development of best-in-class Boards of

Directors. We are experts in recruiting board

memberswho fulfill the highest priorities of

today's best-managed companies, includi ng

executives with financial expertise, operating

depth, strategic acumen, and those who

enrich the diversity of the board. For more

information about Heidrick & Struggles, visit

www.heidrick.com.

Joie Gregor

Vice Chairman

212-867-9876

John Gardner

Vice Chairman

312-496-1000

RED OUTLINE INDICATES BLEED. IT DOES NOT PRINT.

Hei d ri ck & Stru ggl e s

Corporate Social Responsibility

A UNIFI Company

Special BonuS:

Critical Issues

2 0 0 7

A s p o n s o r e d s u p p l e m e n t t o

d I r e C t o r s & B o A r d s B o A r d r o o m B r I e f I n g

Advisories

from Drinker Biddle

and Calvert

2004 KPMG International. KPMG International is a Swiss cooperative which performs no client services. Services are provided by member firms.

KPMGs Audit Committee

Institute (ACI) was formed in

1999 for the sole purpose of

providing audit committees

and those that support them

with meaningful dialogue

and resources focused

on their evolving financial

oversight role. Through

valuable programs like the

ACIs semiannual Roundtables,

topical publications, and

KPMGs biweekly electronic

publication Audit Committee

Insights, we continue to

offer the kind of objective,

usable information needed in

a rapidly evolving corporate

governance environment.

Its a job that was important

in 1999, and is even more

important today.

www.kpmg.com/aci

Since 1999, our

Audit Committee

Institute

has listened

and responded

as audit

committees

dealt with

increased

demands.

Its the job

the ACI

was made for.

To receive KPMG's Audit Committee Insights,

visit www.kpmginsights.com.

FAD0904_ACI_specs8.qxd 9/17/04 4:11PM

B o A R D R o o m B R i E f i N g : C o R p o R A t E S o C i A l R E S p o N S i B i l i t y

Whats Fair, and Whats the Bottom Line? ........................................................ 4

James Kristie

A New Business Model for the 21st Century ...................................................... 6

Bradley K. Googins

CSR: Is it Corporate Irresponsibility? ............................................................. 8

Betsy S. Atkins

From Shareholders to Stakeholders: the Corporate Boards Newest Challenge .... 10

Deborah Talbot

Corporate Social Responsibility Strategy and Boards of Directors .....................12

Herman B. Dutch Leonard and V. Kasturi Kash Rangan

Practicing Social Responsibility from the Heart ............................................... 16

Bonnie W. Gwin and Torrey N. Foster

The Directors & Boards Survey: Corporate Social Responsibility .......................20

Critical Issues 2007 .........................................................................................23

Legacy Programs and Director Independence ..............................................24

Douglas Raymond

Climate Change and Investment .................................................................26

By Julie Fox Gorte

Is Your Corporate Reputation a Liability On Your Balance Sheet? ......................32

By Deborah E. Wallace

Philanthropy Becomes Strategic ......................................................................34

Mary Donohue and Ken Neal

Creating a Culture of Responsibility ................................................................36

Tom Krause and John Balkcom

How Communities Beneft From Corporate Social Responsibility ......................40

James C. Hood

Boardroom Briefing

Vol. , No. 4

A publication of

Directors & Boards magazine

David Shaw

gRiD media llC

Editor & publisher

Scott Chase

gRiD media llC

Advertising & marketing Director

Nancy maynard

gRiD media llC

Account Executive

Directors & Boards

James Kristie

Editor & Associate publisher

lisa m. Cody

Chief financial ofcer

Barbara Wenger

Subscriptions/Circulation

Jerri Smith

Reprints/list Rentals

Robert H. Rock

president

Art Direction

lise Holliker Dykes

lHDesign

Directors & Boards

1845 Walnut Street, Suite 900

philadelphia, pA 1910

(215) 567-200

www.directorsandboards.com

Boardroom Briefng:

Corporate Social Responsibility

is copyright 2006 by mlR Holdings

llC. All rights reserved. poStmAStER:

Send address changes to 1845 Walnut

Street, Suite 900, philadelphia, pA

1910. No portion of this publication

may be reproduced in any form

whatsoever without prior written

permission from the publisher. Created

and produced by gRiD media llC

(www.gridmediallc.com).

W i n t e r 2 0 0 6

4 B o A R D R o o m B R i E f i N g : C o R p o R A t E S o C i A l R E S p o N S i B i l i t y

W

hen I

read the

words or

hear the term

corporate social

responsibility,

what I often

sense is that the

term is code for

the question,

Whose company is it anyway?

Whose company, indeed? Is the

company simply a pass-through

mechanism to process incoming

revenue for return to the owners in

share appreciation and dividends?

Or is the company a citizen of the

society in which it does business,

with a responsibility to be right

thinking to its various stakeholders

the employees, community, suppliers,

and others beyond the core owner

constituency? The shareholders vs.

stakeholders theory, in stripped

down form.

Talk about stripped down.

Remember Al Dunlap? For a brief

shining moment he electrifed the

capital markets with his gonzo

shareholder supremacy theory.

Here is vintage Dunlapian CSR as it

appeared in the pages of Directors &

Boards in a mid-1990s edition:

The one fact of life that is grossly

overlooked is that the shareholders

own the company. It is unbelievable

how boards and executives ignore

this reality. Shareholders take all

the risk. The company that gives

the shareholders back their money

is a company that can ignore the

shareholder. Otherwise, shareholders

are who you work for. They are the

No. 1 constituency. Show me an

annual report that lists six or seven

constituencies and Ill show you a

mismanaged company.

Thats the one school of thought, and

it has its compelling logic and strong

adherents. Now for an on the other

hand interpretation of CSR. I was

always taken with a story that Robert

Mercer, a retired (after 42 years with

the company) chairman of Goodyear

Tire and Rubber Co. recounted in our

pages. Its a good one:

The driver of a Goodyear truck

was at fault in a traffc accident in

Washington, D.C. His truck hit a

restored Volvo driven by a woman who

had been widowed just two weeks

earlier. Her late husband had spent a

great deal of time restoring the car.

The traditional knee-jerk procedures

went into effect, and the widow was

contacted by our insurance carrier.

The contact was an impersonal knock

on the door, by a guy who handed her

a check for $500, the Blue Book value

of the old Volvo. No consideration

was given to the intrinsic or the

sentimental value of the car.

Fortunately, one of our guys

noticed what had happened. Our

employee felt uncomfortable about

the fairness of the settlement, so he

contacted headquarters and explained

the story. He was told to buy the

woman a new Volvo.

None of us knew the woman or any

information beyond the facts of the

story, and it was all but forgotten

when, two months later, I was

approached by a congressman. He

introduced himself, then continued

to say that he was impressed with

Goodyear. He described us as a

very humane company, and I was

compelled to ask how he had formed

that opinion. He relayed the story of

the wrecked Volvo and the widow

whose father, it turns out, had been

a government offcial. And he added

that the story had circulated across

Capitol Hill with a great deal of

positive reaction.

I was delighted to fnd reinforcement

for a decision based on fairness,

not just on the bottom line. No one

knows how far this example may

have reached.

Its still reaching out there, thanks to

my dusting it off for this Boardroom

Briefng in which we explore the nature

of corporate social responsibility in

the 21st centurywhat it is and how it

should be practiced.

Do we want a world run by the

Dunlapian code of shareholder

supremacy? When the Blue Book

i.e., the bottom line, the strict

fduciary obligationreigns supreme,

there would be no new Volvo to

soothe a wronged widow. Or do we

want a world where the shareholders

return gets trimmed in the cause of

fair dealing and societal obligation?

Or can we have both?

James Kristie is editor and associate publisher

of Directors & Boards. He can be contacted at

jkristie@directorsandboards.com.

James Kristie

Whats fair, and Whats the Bottom line?

By James Kristie

Beyond the Blue Bookor not. Corporate social responsibility enters an era of investor activism.

AlixPartners professionals have conducted

large-scale internal investigations in some of the most

complex corporate accounting matters in history. Were

independent and objective, and will help you find solutions.

Our team of professionals includes certified public accountants,

certified fraud examiners, computer forensic technology

experts and other experienced investigators.

For more information about how our Corporate Investigations Practice

can help you, contact Harvey Kelly at (646) 746-2422.

www.alixpartners.com

Chicago Dallas Detroit Dsseldorf London Los Angeles Milan Munich New York Paris San Francisco Tokyo

Minding your business... Minding your business...

... or peace of mind?

6 B o A R D R o o m B R i E f i N g : C o R p o R A t E S o C i A l R E S p o N S i B i l i t y

L

ike it

or not,

business is

being pulled

into social

issues and

public debates

most would

prefer to avoid.

Gone are the

days when the private sector was

expected to simply create jobs,

deliver goods and services, increase

shareholder wealth, and demonstrate

goodwill to the community through

philanthropy.

While few executives are seeking

airtime to spread this message, many

recently shared these opinions with

the Center for Corporate Citizenship

at Boston College as part of a

research project exploring the role of

business in 21st century society. We

interviewed 48 senior executives, a

majority CEOs, representing a wide

array of multinational companies

including Citigroup, IBM, GE,

Raytheon, Nestle, Ernst & Young,

Baxter International.

The research clearly shows that

leaders of successful companies

recognize the Milton Friedman

business model has lost its relevance

in the 21st century. While some

still hold onto it for a sense of

security, most responsibleand

successfulleaders know business

cannot succeed if society fails. Some

71 percent of those interviewed said

that societal issuesfrom climate

change, health care, pension reform,

income disparitypose challenges

to their business success. Over half

talked about managing their social

impact as an asset, and nearly all

refute the concept that short-term

proft maximization is a companys

single virtue.

Jeffrey Immelt, GEs Chairman and

CEO told the Center: Profts are

created by businesses that are doing

things that ultimately have real

societal benefts. And businesses

have not done a good job describing

that. Immelts comments are

clearly refected in GEs innovative

ecomagination initiative.

a new Reality is emerging

As the old business model cracks,

a new reality is emerging as more

companiesincluding those small

and locally-basedrealize they are

managing in a global marketplace

that involves a complexity that

requires they focus far beyond

traditional shareholders. IBM

Chairman and CEO Sam Palmisano

described this new reality: What

is different about business now is

that the concept of shareholders has

changed to stakeholders.

The challenge at the top tier of

business is to engage in public

debates in a manner that refects the

new role of business and its bottom-

line interests. Leading companies

that are doing this well are clear

about why they are participating

in these issues and are proactively

infuencing the agenda and

conditions by which they participate.

Companies need to commit to smart

and selective engagement with the

many individuals, community-based

organizations and advocacy groups

that expect them to address

societal issues.

Part of the new reality for business

is a result of the changing role and

capacity of government worldwide.

As governments downsize and are

pressured to privatize many public

services, many are recognizing

that business has the competencies,

resources and infrastructure to help

meet societal challengesthis was

magnifed when Hurricane Katrina

hit the Gulf region. The question now

is not so much what business has to

offer, but where should be the limits

to what it does and how it acts.

Companies wanted a freer hand

in terms of government regulation,

and restrictions on their business

activities. And I think with that

freer hand comes an obligation.

You cant ask for one and not

deliver on the other, said James S.

Turley, Chairman and CEO of Ernst

& Young.

The investment community has no sense

of social responsibility. And when I say no sense,

I cant use smaller words than that.

Bradley K. Googins

A New Business model for the 21st Century

By Bradley K. Googins

Most responsibleand successfulleaders know business cannot succeed if society fails

B o A R D R o o m B R i E f i N g : C o R p o R A t E S o C i A l R E S p o N S i B i l i t y 7

The Barriers of Short-Termism

As business leaders try to sort out

their long-term responsibilities to

society, they are often confronted by

the conficting short-term demands of

investors. The investment community

was cited by a majority of executives

interviewed as a signifcant obstacle

for their company to engage with the

new socio-economic realities of the

business environment.

The mark of a truly successful

business is one that takes into

consideration the views of Wall Street

and investors and analysts as but one

vector. They are an important vector

that has to be considered, but its

only one vector out of all the others

you must consider and balance, said

InBev CEO John Brock.

However, they also say its a cop out

to place all the blame on investors.

Many said they are beginning to

communicate the changing climate

to investors, and especially the

all-important sell-side analysts.

But there is a long way to go. The

investment community has no sense

of social responsibility. And when

I say no sense, I cant use smaller

words than that, said Citigroup

Chairman and CEO Charles Prince.

It will take concerted, persistent

effort to persuade investors to think

in terms of proft optimization

rather than maximization, and

for companies to treat the need to

produce profts not as an end, but

a signal that companies are doing

what society wants.

a Soft-landing to Globalization

The most dominant driver of

the changing business-society

relationship is globalization. While

it has brought great benefts to

business, it has also introduced

new risks and uncertainty. Getting

involved in dealing with the

consequences of globalization is

one area where business can fnd

solutions to societal expectations

and communicate a consistent

message about its role in society.

Business doesnt have to take this

on alone: creating a soft landing

to globalization lends itself to

partnerships with government and

civil society. The solutions are often

ones that enhance reputation, create

new business opportunities, and build

public trust. And whats more they

arent about turning back the clock.

Sixty-fve percent of the worlds

wealth is here in the United States,

said Phil Marineau, former President

and CEO of Levi Strauss & Co. Were

watching it being redistributed

before our eyes. How do companies

participate in a way that is consistent

with their values, and that earns

peoples trust? To provide this soft

landing a company should consider

providing a benefts package that

helps workers and their families

thrive, looking for ways to keep

employees skills relevant in the job

market. These approaches require a

company to acknowledge the old

(continued on page 42)

It will take concerted, persistent efort

to persuade investors to think in terms of

proft optimization rather than maximization.

8 B o A R D R o o m B R i E f i N g : C o R p o R A t E S o C i A l R E S p o N S i B i l i t y

T

he concept

of corporate

social

responsibility

is one that

deserves to

be challenged

and examined

carefully. It

is absolutely

correct to expect that corporations

should not be irresponsible and

should comply with all laws and

regulations, creating quality products,

marketed in an ethical manner, in

compliance with laws and regulations

with fnancials represented in

an honest transparent way to the

shareholders. However, the notion that

the corporation should apply its assets

for social purposes rather than for the

proft of its ownersthe shareholders

is an irresponsible use of assets.

The board of directors, on behalf of the

stockholders, has responsibility to hire

the CEO (and executive management)

and oversee and measure them on

the profts that they achieve. The

shareholders can certainly spend

their own money/assets on socially

responsible charities that promote

causes they believe in. However, if the

CEO and executive management team

of the corporations whose stock the

investors purchased decides to deploy

corporate assets for social causes, this

would not be responsible.

Would You pay More?

A real litmus test of the market for

social responsibility (defned as social

causes) by a corporation could certainly

be tested. Apple Corporation, for

example, could have an iPod for $99

and the same iPod for $125. The more

expensive iPod could be designated

so that the extra $25 would be used

for specifc social causes, such as

retraining hard core unemployables,

donating to causes to lower pollution,

etc. This market test would be a clear

and an honest way of accounting for

the shareholders money. This would

allow the market to decide and drive

the outcome. If there are enough

consumers who wanted to pay the extra

$25, those consumers could do so.

A questionable use of corporate

assets would be for a corporation

to invest the shareholders money

in a social cause such as lowering

environmental pollution by building

a green corporate headquarters that

cost an extra $100 million. This is

not a responsible use of shareholders

money. In fact, it is irresponsible and

deceptive. The corporation hasnt

asked the shareholders permission if

they want their assets spent this way.

Management is charged with making

informed decisions to invest corporate

assets for the highest and best use,

to achieve corporate goals of growth,

proftability, product innovation, etc.

to drive a return on investment for

the shareholders. What measurable

outcome could such a management

re-deployment of corporate assets for

a Green Headquarters have?

It is the private individuals choice and

right to decide to support charities

and social causes they believe in.

I do not believe that the investing

public considers their for-proft public

corporate investments to be part of

their social charitable causes.

pc Rhetoric

There are practical reasons why

corporations should cloak themselves

in the current politically correct

rhetoric of social responsibility. But

this marketing cloakware should

not be confused with an actual

signifcant redeployment of corporate

assets. One can look at British

Petroleums marketing efforts, which

is all about being a green company.

This makes the consuming public

feel good about purchasing British

Petroleum products. Corporations

should want their consuming and our

investing public to feel good about its

market messaging. However, dont be

confused: if British Petroleum were to

redeploy billions of dollars of corporate

assets into nonproft yielding social

investments and the stock plummeted,

one can certainly expect that the

investing public would transfer its

investments to BPs competitors.

We should not confuse the rhetoric

and parlance of social responsibility.

(continued on page 42)

What the investing and consuming public expects of its for-

proft public corporations is that they not be irresponsible.

Betsy S. Atkins

CSR: is it Corporate irresponsibility?

By Betsy S. Atkins

I do not believe that the investing public considers their for-proft public corporate investments

to be part of their social charitable causes.

C

u

s

t

.

:

P

A

N

G

A

R

O

6

1

3

3

9

5

D

a

t

e

:

1

1

-

2

-

0

6

D

e

s

c

.

:

H

B

S

D

i

r

e

c

t

o

r

s

&

B

o

a

r

d

s

_

V

2

L

S

:

1

3

3

1 0 B o A R D R o o m B R i E f i N g : C o R p o R A t E S o C i A l R E S p o N S i B i l i t y

M

aking

money

making

lots of moneyis surely central to

why corporations exist. But more

and more these days it appears that

corporations are being challenged to

do more, to be more. And in many

cases it is the shareholder, the very

constituent who elects corporate

directors, who is raising the bar.

Corporate social responsibility is the

term most often used to describe an

evolving dialog that seeks to expand

the role of the corporation beyond

the economic frame to include

social and environmental aspects

of community. Of course, there are

many on both sides of the board

table who believe if we make money,

we are being socially responsible

by providing jobs and economic

value to the community. If we keep

shareholders happy, then we have a

successful enterprise.

However, broadening accountability

beyond shareholders to include

employees, customers, suppliers,

competitors and the community

signifcantly challenges not only

the values of the corporation but

the boards role in overseeing this

accountability shift. CSR goes

beyond philanthropy. It is not so

much about giving back but

making right. It is about corporate

sustainabilityoperating in such

a way that sustains the health,

viability and relevance of all who

have a stake.

Broadly stated, CSR refects a

concern for the three Ps: profts,

people (employees, customer and

citizens) and place (environment

and community). By no means

is proftability of the corporation

set aside but rather supplemented

by additional considerations that

go beyond fnancial success.

Furthermore, while socially

responsible action may initially

reduce profts, many corporations

are fnding that it may also create

new opportunities for adding to

profts and/or reduce a greater threat

of operating losses due to legal/

regulatory actions or loss of favor in

the marketplace.

How Did cSR come to Be?

CSR derives from a broader

emerging aspect of our culture

where huge societal issues of

sustainability are emerging--not just

natural sustainability or the health

of our planet but also such nagging

problems as education, the aging

workforce, healthcare and related

wellness issues, and an underlying

loss of community.

What are a corporations

responsibilities for generating social,

not fnancial, capital? What are

some of the consequences of CSR?

How can its success be measured?

To understand some of these

questions, lets look at what some

companies are doing under the

CSR umbrella. Disney recently

announced it would no longer

contribute to childrens obesity

by gracing high fat/sugar content

food with its colorful characters.

Lucrative licensing deals with

companies such as McDonalds,

Coca Cola and Kellogg will not be

renewed if their products do not

meet the new guidelines issued by

Disney. Furthermore, Disney has set

a goal to remove all trans fat from

their theme parks by 2007 and their

licensed products by 2008. None of

these decisions is going to seriously

threaten the proftability of Disney.

They are being made over time in

a planned process and somewhat

in response to actions taken by

competitors, activists and the

collective action of their management

and board in assessing the espoused

values of the Disney corporation.

Nor is this the extent of Disneys CSR

effortsthey are developing a cogent

and effective story on responsible

corporate enterprise that matches

their corporate values/mission.

The growing customer preference for doing business with

companies who make right may indeed spawn

one of business most creative/innovative periods.

Deborah Talbot

from Shareholders to Stakeholders:

the Corporate Boards Newest Challenge

By Deborah Talbot

CSR goes beyond philanthropy. It is not so much about giving back but making right.

B o A R D R o o m B R i E f i N g : C o R p o R A t E S o C i A l R E S p o N S i B i l i t y 1 1

Philips is focused not only on

environmental sustainability

reducing the level of energy in their

lighting products and servicesbut

also on changing the way people

interact with their products in order

to reduce harmful side effects. By

working with children, their parents

and the centers that operate their

medical equipment, Philips has

created special effects that reduce

the fear and trepidation of medical

scanning devices, reducing by

over 30% the number of children

requiring sedation. One of Philips

core values is innovation and they

use their 450-person design unit

to create business opportunities

that support their social and

environmental values.

The Boards Role

What should the boards role be in

the realm of CSR? Get involved. Do

not let CSR become a side issue to be

addressed outside the main business

channel. To do so will, in the long

run, prove more costly and seriously

deter credible, creative business

development. Social responsibility

needs to be addressed within the

business planning process of the

corporation or opportunities to

improve the bottom line will be lost.

Develop a Scorecard for CSR

oversight. The scorecard would be

unique to each corporation and

developed jointly with management

and should consider the following:

Values Review. Review with

management the corporations

values as set out in various corporate

documents and align values

with performance. Expand the

values/mission of the corporation

as necessary to address proft,

people and place. Play upon the

corporations competitive strengths in

expanding the business paradigm.

Do No Harm. This is a challenging

principle for corporations to address

what are the consequences of the

products/services we sell and the

business practices we embody? Can

we defend these products/practices in

a growing climate of accountability

that includes environmental and

business sustainability as well as

community well-being?

Transition Accounting. Ask

management to propose measures

to offset or complement current

fnancial measuresboth internally

and within the external community

of analysts and investors. Some

corporations have developed a

sustainability or CSR annual report

that supplements their fnancial

reporting. Focus on innovative ideas/

design for better business which

generally warrant new measures.

Long-term CSR Plan. Work with

management on developing a

comprehensive long-term plan to

address where the corporation wants

to go relative to this expanded

accountability.

Do not be put off by the evolving

nature of this movement

understand that goals may shift as

technology and business practice

evolves. Develop your own corporate

storydo not let the marketplace or

outside forces dictate your story.

Also do not assume that if you

ignore it, CSR will go away. Your

response to CSR may not only

allow the business to avoid costly

reactionary measures and possible

regulatory/legal actions but

may indeed enrich the corporate

coffers through innovative design

and differentiation. The growing

customer preference for doing

business with companies who

make right may indeed spawn

one of business most creative/

innovative periods.

Dr. Deborah Talbot is a strategic consultant,

independent director and social entrepreneur

based in Tampa, Florida. A former senior executive

at JPMorgan Chase, she has served boards in

fnancial services, education, and not-for-profts

in a variety of capacities. Dr. Talbot is currently

writing a book based upon her doctoral research

that examines a new model of capitalism. She can

be reached by e-mail at dtalbot13@mac.com.

1 2 B o A R D R o o m B R i E f i N g : C o R p o R A t E S o C i A l R E S p o N S i B i l i t y

C

ompanies

today face

increasing

demands for

corporate

social

responsibility

(CSR).

Correspondingly,

they have

important new

opportunities to

build business

value through

judicious

choices and actions to improve

social and environmental conditions

in the communities in which they

do business. Whereas frms once

might have been able to prosper

by concerning themselves almost

exclusively with fnancial results,

most now fnd it at least prudent

and many are fnding it directly

valuableto manage a wider array

of the impacts that they generate (or

can infuence), from environmental

conditions to employee health and

safety to social conditions like the

quality of public education.

How can boards best organize

themselves and act so as to add

perspective and value in these

matters? First, they must develop the

capacity to examine and evaluate

individual CSR-oriented actions,

a process that requires both an

understanding of the motivation

behind them and an assessment

of their impact on society and on

the frm. Second, they need to

ensure that the frms CSR activities

constitute a coherent and effective

CSR strategy. Third, they have to see

to it that their frms CSR strategy

and decision-making are integrated

into the companys overall strategy.

Start with the

Softest investments,

and Build Your Way out

Generally, it is not a good idea to

start by reviewing all CSR efforts

at once. Firms engage in a variety

of activities in manufacturing, in

their supply chain, and in cause

marketing that already commands

the attention of appropriate

operational leaders. Detailed

oversight by directors may be

unwarranted, and will likely be

unwelcome. Instead, directors

should frst examine the things

in which they are most directly

involved: the frms charitable

activities, especially its largest ones.

Most companies engage in some

form of philanthropic activity

either through direct donations

or a corporate foundation. Look

especially carefully at the soft

activities that do not mesh with

the business activities of the frm,

either on the input or the output

side. See whether and how they

are supposed to generate value for

the frm. Is there a reason why we

should support these activities? Are

we more interested in these specifc

social benefts than others, or in

a better position to help promote

them because of our position in the

industry or our connections in the

supply chain, both upstream with

suppliers and downstream with

customers? Or are there, instead,

other activities that make more

sense for us to support?

This is an area where a board can

add value. Most companies engage in

a variety of unconnected charitable

activities at the behest of one senior

leader or another, somehow hoping

that in the long run, this will

embellish the companys reputation.

It is the boards job to bring

coherence to these investments

frst, because it is their fduciary

responsibility, but more importantly

because they can bring a visionary

assessment of how such activities,

when properly integrated, can deliver

future value for the frm.

Next, check out your core business

processes to identify their

larger social consequences. For

example, inquire whether your

manufacturing processes could

Herman B. DutchLeonard

Corporate Social Responsibility Strategy

and Boards of Directors

By Herman B. Dutch Leonard and V. Kasturi Kash Rangan

How can boards best organize themselves and act so as to add perspective and value with CSR?

V. Kasturi KashRangan

Detailed oversight by directors may be unwarranted,

and will likely be unwelcome.

B o A R D R o o m B R i E f i N g : C o R p o R A t E S o C i A l R E S p o N S i B i l i t y 1

be made more effcient to reduce

waste and environmental impact

(and, simultaneously, your costs),

and whether your products can be

designed to use less packaging or

be more readily recyclable. Much of

the homework on this audit should

already have been done by the

operational managers. The boards

role here is simply to ensure that the

pieces of the puzzle are put together,

enabling it to see and shape the

frms larger CSR strategy.

Finally, work your way out from

the center of your own activities,

in two directions: up your supply

chain to vendors, and down your

value chain to customers. Make

sure management has looked at its

purchases of raw materials. Are

they sustainably harvested? Would

it make sense for the company

to work with its suppliers to help

them address working conditions

in their factories in ways that

would also improve worker morale

and productivity (and thus, not

incidentally, lower costs)? Can you

work with your customers to reclaim

and recycle parts of your products

after theyve been consumed? Are

your cause marketing programs and

community relations activities truly

building your brand?

examining individual

philanthropy-related

actions and activities

To judge the merits of individual

CSR-related programs or activities,

board members must understand

their basic purpose. Directors can

begin by recognizing the various

reasons why companies might

engage in activities that, in the frst

instance, create social value rather

than directly produce fnancial

results. One reason may be a sense

of moral obligationbecause

Most companies engage in a variety of

unconnected charitable activities at the behest

of one senior leader or another, somehow hoping

that in the long run, this will embellish the

companys reputation.

1 4 B o A R D R o o m B R i E f i N g : C o R p o R A t E S o C i A l R E S p o N S i B i l i t y

they (and/or their shareholders,

managers, and fellow directors)

believe it is the right thing to

do. When there is an important

social problem (such as 9/11 or the

aftermath of Katrina), and the frm

is in a good position to do something

about it, the frms owners and

leaders may agree that they want to

take action simply out of a sense of

moral concern.

Moral obligations aside, companies

more commonly act on social

matters because they see a business

case for social response. They believe

that, in either the short or longer run,

such a strategy will produce direct

benefts for the frmas, for example,

with efforts to reduce environmental

impact, which improve production

effciency, eliminate waste, and

reduce input costsor will result in

indirect advantages (whose benefts

may take longer to recognize). For

instance, a program that allows

employees paid time to volunteer

in local nonproft activities may

build support in the community that

might later improve opportunities

for getting more favorable regulatory

treatment from local offcials.

In contrast, we fnd that frms are

often vague about why they are

pursuing specifc activities. When

asked, they can say little more than

that it seemed like a good idea or

that they felt that they should do

something. Our view is that the

more explicit they can be about their

intentions, the more likely they are

to achieve real resultsfor society

and for the frm.

If the intent of the program is (at

least in part) to generate value

for the frm, boards should also

examine whether a given action

is basically defensive or is part

of a strategy to create new value.

Businesses can pursue CSR actions

either to protect existing value (for

example, to keep from losing the

ability to operate in a country or

community, or to avoid a possible

boycott of its goods)or to create

new value (as when they access a

new market segment by adapting

products or services to address the

needs of low-income populations).

overseeing the Building

and operation of a Firms

cSR Strategy

Once the board understands the basic

theory of value of a given activity

how and why it is supposed to create

value, and for whomthe next

challenge is to assess whether it is in

fact working. The board needs to see

to it that performance objectives have

been set, that indicators of success

have been established and are being

monitored, and that processes are

in place for learning about how

the program can be improved on a

continuing basis.

Beyond examining individual

components of the frms CSR

activities, the board must face the

larger responsibility of ensuring that

the frm has a coherent collection of

CSR activities that are aligned with

one another and with the overall

strategy of the frm. Well-intentioned

CSR activities with little intrinsic

connection to the frms skills and

main business strategy are likely

to create management distractions

rather than build frm value.

In reviewing the CSR portfolio,

boards must therefore examine the

coherence of the CSR strategy as

a component of the frms overall

strategy by asking:

How do these actions ft together

with one anotherand with our

general strategy?

Is the CSR strategy internally

coherent?

Does our approach to CSR take

advantage of our key skills and

distinctive competenciesor

does it require us to develop

new capabilities that we do not

otherwise need?

Are decisions about CSR integrated

into our basic business systems

and decision processes?

When individual CSR activities

are carefully understood so that

we know why we are undertaking

them, what results we expect

from them, what their impact is,

and how we can improve them

over time, and when we have

formed a coherent collection of

these activities and integrated our

decision-making about them into

our main business strategy, CSR

will become an ongoing company

function that builds long-term

value for shareholders as well as

stakeholders.

Dutch Leonard and Kash Rangan are both

professors at Harvard Business School and co-

chairs of its Social Enterprise Initiative (www.

hbs.edu/socialenterprise). They teach the HBS

Executive Education program titled Corporate

Social Responsibility: Strategies to Create Business

and Social Value.

Moral obligations aside, companies more commonly act on social matters

because they see a business case for social response.

You cant outrun change,

but you can outthink it.

You cant just wait for change. You have to confront it head on. Sharpen your skills in the Columbia

Business School Executive Education Programs. Together with the Columbia Business School faculty

and peers from around the globe, youll maximize your effectiveness, enhance your managerial

skills, and take on the issues of our rapidly changing world. Theres no time to wait. Join us next year.

The Columbia Senior Executive Program

April 29-May 25

Leading Strategic Growth and Change

May 6-11

Enhancing Financial Integrity: Critical Accounting Issues for Corporate Directors

May 14-16

To learn more:

www.gsb.columbia.edu/execed/boardroombrief

or call (212) 854-0616

483- Columbia Business School

Boardroom Briefing

Page 4/C

Insertion date(s): Dec. 6

Close 11/3

Gardener-Nelson & Partners: 212-584-9100

1 6 B o A R D R o o m B R i E f i N g : C o R p o R A t E S o C i A l R E S p o N S i B i l i t y

A

seismic

generational

shift

has greatly

heightened the

importance of

corporate social

responsibility

(CSR) in

attracting the

best and the

brightest talent

to leading

companies.

We have found

that candidates

from so-called

Generation X

and Generation

Ythe two

demographic

cohorts that succeeded the baby

boomersincreasingly insist that the

companies they work for embrace

socially responsible practices.

Believing that the invisible hand of

the market should be supplemented

by the helping hand of social

responsibility, they want to see their

individual values writ large in the

corporation. The implication for

boards is clear: To help ensure a long-

term supply of top talent, they must

recognize that social responsibility

is profoundly important to the next

generation of leaders and explicitly

work with management in endorsing

and evaluating CSR programs.

While a companys CSR practices

may not be the primary factor in a

candidates decision to accept an offer,

it can certainly heavily infuence

candidates as they go through their

due diligence about a potential

employer. Imagine, for example, a top

executive who has been offered similar

packages from competing companies.

One is Starbucks, widely known for

its determination to go beyond the

cup through its commitment to

sustainable agriculture, diversity and

socially responsible investments.

The other offer comes from a company

that is indifferent to the plight of

farmers and has little interest in

sustainable agriculture.

In terms of recruiting an executive

to Starbucks, there is no question

that CSR is a tie breaker, says Craig

Weatherup, former Chairman &

CEO of the Pepsi Bottling Group and

current board member for Starbucks

and Federated Department Stores.

The young executives I know who

are future CEO candidates all have

a great deal of interest in these

questions about their companies: Are

we living our values? What are we

doing to make them real? In the old

days, maybe twenty-fve percent of

the CEO universe would not go near

certain kinds of companies for social

reasons. Now, twenty-fve percent

really look for the social reasons to

join a company.

As further illustration, a typical high-

profle candidate told us, I want to

work at a place where its not just

about the bottom line, but also about

humankind and the chance to make a

difference.

Beyond such anecdotal evidence,

confrmation of heightened interest

in social responsibility on the part of

the rising generations of leaders may

be found in the 2006 list of 100 Best

Corporate Citizens issued by Business

Ethics magazine (now part of CRO

magazine, devoted to the emerging

role of the Corporate Responsibility

Offcer). Using a variety of statistical

and analytic techniques, the list

embodies numerical rankings of

major U.S. companies on the basis of

service in eight areas: stockholders,

community, governance, diversity,

employees, environment, human rights

and products. Tellingly, eight of the top

10 best corporate citizens on the 2006

list are technology frmsincluding

Advanced Micro Devices, Agilent, Dell

and Motorolaa sector that has long

been a magnet for highly educated,

ambitious members of Generation

X and Generation Y, some of whom

founded Silicon Valleys most dynamic

companies. These frms know that to

attract and retain talent, it pays to be

socially enlightened, says Marjorie

Kelly, editor of Business Ethics. High-

tech seems to be a genuinely socially

responsible sector.

embracing the paradox

Although a companys attention

to social responsibility can be a

signifcant incentive for candidates,

Bonnie W. Gwin

practicing Social Responsibility from the Heart

By Bonnie W. Gwin and Torrey N. Foster

What boards need to know about the paradoxical role of CSR in recruiting

Torrey N. Foster

In terms of recruiting an executive to Starbucks,

there is no question that CSR is a tie breaker.

B o A R D R o o m B R i E f i N g : C o R p o R A t E S o C i A l R E S p o N S i B i l i t y 1 7

boards must understand that insofar

as CSR is adopted merely for its

instrumental value as a recruitment

or public relations tool, many of the

candidates we talk to are likely to be

unmoved. The commitment to social

responsibility must be authentic,

not just a matter of boilerplate in the

mission and values statements. The

prospective employer must practice

CSR from the heart.

Life is too short, says a recent senior

executive candidate, whose views are

typical of the high-performing, high-

potential candidates we encounter.

I want to be part of an organization

that isnt just about high performance

but that also cares about people and

the communities they live in. They

have to walk the talk toonot just

talk about it but have real programs

and measurements.

As boards evaluate the human capital

implications of their companies CSR

practices, its not enough to simply ask

if acceptable policies are in place. They

should ask management the questions

that candidates ask to determine

whether the company really means it:

Is CSR woven into the fabric of

the companys business? While

candidates welcome the long-familiar

practice of philanthropic donations

to worthy causes, many of the people

we talk to also believe that social

responsibility should relate directly

to the business of the company.

Whirlpool, appropriately for a maker

of household appliances, is the largest

single corporate sponsor of Habitat for

Humanity and by 2011 will be involved

in every single dwelling that Habitat

builds anywhere in the world. The

company is also determined to produce

environmentally friendly products,

and through its KitchenAid brands

Cook for the Cure program, Whirlpool

supports breast cancer research.

Corporate social responsibility is a

core value of the company not only

because its the right thing to do, says

David L. Swift, President, Whirlpool

North America, and a member of

the board, but also because its

a key driver of brand loyalty with

consumers today and it builds passion

and loyalty among our employees.

The companys efforts to integrate CSR

with the nature of its business have

not gone unnoticed: Whirlpool has

made the Business Ethics list all seven

years of the lists existence, and in

September the company was named to

the 2006/2007 Dow Jones sustainability

World Index (DJSI), an international

stock portfolio that evaluates corporate

performance using economic,

environmental and social criteria.

Similarly, Novartis, whose Foundation

for Sustainable Development has been

a leading voice on development issues

for more than 25 years, has partnered

with international organizations such

as the World Health Organization to

provide medicines against malaria,

leprosy, and tuberculosis to millions of

people in the worlds poorest countries

at no proftor sometimes for free. In

addition, the company has engaged in

social marketing to convince people

with leprosy that it is treatable and then

provided medicine for them. Novartis

has also developed programs to help

orphans of AIDS, and it has pioneered

an experiment in bringing health

insurance to the rural poor in Africa.

Are the boundaries of responsibility

broadly drawn? Along with regulators,

activists, labor unions, the press, and

communities, the rising generation

of leaders increasingly sees corporate

responsibility not only as a matter of

a companys behavior, but also the

behavior of its partners throughout

the value chain in matters like labor

practices and the environment.

Starbucks, through its Coffee and

Farmer Equity (C.A.F.E.) program,

seeks to instill sustainable agricultural

practices along its entire coffee

supply chain, efforts that have been

recognized as a model by many

throughout the coffee industry.

Is purchasing and investing power

used responsibly? Because company

purchasing power can contribute to

economic development in places that

badly need it, targeted programs can

be especially strong indicators of a

companys commitment to genuine

CSR. For example, The Body Shop, the

UK-based chain of cosmetics stores,

pursues a Community Trade program

that purchases accessories and natural

ingredients from disadvantaged

communities around the world.

Is CSR practiced locally as well as

globally? Recalling the Renaissance

notion of the individual as a

microcosm of the universe, many of

the new generation of leaders want

to see their individual values scaled

up in the company, beginning with a

commitment to the local community.

Novartis, clearly understanding this

connection, says that the company

wants to act the same way as

responsible and conscientious

individuals would act in their

community. Target donates more than

$2 million each week to local nonproft

organizations in the communities

Interestingly, we have found that prospective directors,

unlike the rising generation of executives,

rarely raise the question of CSR.

1 8 B o A R D R o o m B R i E f i N g : C o R p o R A t E S o C i A l R E S p o N S i B i l i t y

Today, executive compensation is more complex than ever. Greater competitive pressures.

Increased regulatory demands. Heightened shareholder concerns. As a result, Directors need ever

more complete expertise. Thats why so many organizations, from the Fortune 500 to emerging,

high-growth companies, turn to Pearl Meyer & Partners.

PM&P provides Directors and their Management unique depth and breadth of expertise. Research.

Assessment. Strategy and Planning. Implementation. Compliance. All with just one call. To learn

more, contact us at 212-644-2300 or

visit pearlmeyer.com.

A C L A R K C O N S U L T I N G P R A C T I C E A C L A R K C O N S U L T I N G P R A C T I C E

Pearl Meyer & Partners. Comprehensive Compensation.

SM

Who do you trust to

put all the pieces together

in executive compensation?

2

0

0

6

CC6037_FullSprd 8/7/06 11:01 PM Page 1

where the retailer operates and gets

directly involved in local volunteerism

through Target Volunteers.

Do employees have the opportunity

to act directly for the greater good?

Many companies give their employees

release time to engage in community

service. They may grant a set amount

of paid time for an employee to do

volunteer work during business hours

or may grant paid leave to an employee

to work full-time with a non-proft

organization. The Gap, for example,

came up with a novel scheme when

a number of its stores in Denver were

closed for 10 weeks for renovations.

During this period, store employees

remained on the companys payroll and

divided their time between training

and volunteering with nonprofts in

the area. More than 60 community

organizations hosted Gap employees,

who volunteered nearly 10,000 hours.

Taking the next Step

Merely asking the right questions,

however, isnt likely to suffce. If the

board doesnt genuinely endorse and

regularly evaluate the companys CSR

practices they are likely to be half-

hearted, with negative consequences

for the recruiting of talent.

Interestingly, we have found that

prospective directors, unlike the rising

generation of executives, rarely raise

the question of CSR. This suggests

a potential disconnect between the

boards interest in these issues and

the intense interest of many executive

candidates. To bridge this gap, boards

can make CSR one more metric by

which they evaluate the performance

of management, even incorporating

it into their annual review of the

CEOs performance. Starbucks goes

one step further, issuing an extensive

and detailed Corporate Social

Responsibility Annual Report, signed

by Chairman Howard Schultz and

CEO Jim Donald.

CSR evaluation and reporting need

not be subjective. There are numerous

guidelines and reporting standards,

such as the Global Sullivan Standards

and U.N. Global Compact, for

evaluating performance in specifc

areas as well as CSR performance

generally. Since 2004, Novartis has

been reporting its CSR within the

framework of the Global Reporting

Initiative (GRI), a reporting standard

developed by CERES (Coalition

for Environmentally Responsible

Economies), an organization

encompassing corporations,

non-governmental organizations,

international organizations, United

Nations agencies, business associations,

universities, consultants, and

accounting organizations. The objective

B o A R D R o o m B R i E f i N g : C o R p o R A t E S o C i A l R E S p o N S i B i l i t y 1 9

Today, executive compensation is more complex than ever. Greater competitive pressures.

Increased regulatory demands. Heightened shareholder concerns. As a result, Directors need ever

more complete expertise. Thats why so many organizations, from the Fortune 500 to emerging,

high-growth companies, turn to Pearl Meyer & Partners.

PM&P provides Directors and their Management unique depth and breadth of expertise. Research.

Assessment. Strategy and Planning. Implementation. Compliance. All with just one call. To learn

more, contact us at 212-644-2300 or

visit pearlmeyer.com.

A C L A R K C O N S U L T I N G P R A C T I C E A C L A R K C O N S U L T I N G P R A C T I C E

Pearl Meyer & Partners. Comprehensive Compensation.

SM

Who do you trust to

put all the pieces together

in executive compensation?

2

0

0

6

CC6037_FullSprd 8/7/06 11:01 PM Page 1

of the GRI is to elevate sustainability

reporting to the same level of rigor

and credibility as fnancial reporting.

Novartis 2005 GRI report received the

GRI in accordance check. The Gaps

extensive annual Social Responsibility

Report includes indexes of the

companys performance against critical

GRI and Global Compact indicators.

In addition, because the GRI and the

Global Compact do not yet encompass

some of the most pressing issues in the

apparel industry, such as management

of human rights issues and labor

standards within supply chains, the

report includes a signifcant amount

of data about the companys ethical

sourcing practices that go beyond the

GRI and Global Compact guidelines.

It is certainly not surprising to see

CSR being brought under the general

umbrella of governance and the

boards oversight. After all, much

of the current interest in CSR has

its roots in issues of board diversity,

director independence, and board

accountability.

This convergence of good governance

and social responsibility can also be

seen, for example, in the Governance,

Nominating and Social Responsibility

Committee of the board of directors of

The Gap. Moreover, in a litigious age

and a wired world where a companys

reputation can be badly tarnished

overnight, CSR can certainly be

viewed as an aspect of risk mitigation

and therefore part of the fduciary

responsibility of directors. CSR is

becoming an accepted and even an

expected part of board governance,

says Starbucks board member Craig

Weatherup. The fact that boards are

asking these kinds of questions is to

me a very meaningful evolution in this

country. It is not fuff; it is about the

real direction companies are taking. It

has to be defned by the company. It is

not one size fts allit cant be in order

to be authentic.

Increasingly, boards are creating

committees explicitly tasked with

(continued on page 42)

If the board doesnt genuinely endorse and regularly

evaluate the companys CSR practices they are likely to

be half-hearted, with negative consequences for the

recruiting of talent.

2 0 B o A R D R o o m B R i E f i N g : C o R p o R A t E S o C i A l R E S p o N S i B i l i t y

the Directors & Boards Survey:

Corporate Social Responsibility

Board Service

(Average number of boards respondents serve)

Public 1.17

Private 1.84

Charitable 1.90

Respondents age

Average Age:

54.35

Methodology

This Directors & Boards survey was

conducted in September 2006 via

the web, with an email invitation

to participate. The invitation was

emailed to the recipients of Directors

& Boards monthly e-Briefng. A total

of 430 usable surveys were completed.

about the respondents

(Multiple responses allowed)

A director of a publicly held company 32.2%

A senior level executive (CEO, CFO, CxO)

of a publicly held company 6.1%

A director of a privately held company 30.4%

A senior level executive (CEO, CFO, CxO)

of a privately held company 25.2%

A director of a non-proft entity 37.9%

Institutional shareholder 5.6%

Other shareholder 18.2%

Academic 11.7%

Auditor, consultant, board advisor 16.8%

Attorney 11.2%

Investor relations professional/ofcer 3.7%

Other 9.3%

(Other responses included: director of community

engagement, director of internal audit,

independent mutual funds director, former public

company director, corporate secretary.)

Revenues

(For the primary company of the respondent)

Average revenues: $1.641 billion

Less than $250 million 55.7%

$251 million-$500 million 12.3%

$501 million to $999 million 8.5%

$1 billion to $10 billion 17.9%

More than $10 billion 5.7%

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

21-29 30-39 40-49 50-59 60-69 70+

2.8%

10.3%

16.0%

35.7%

6.6%

28.6%

Corporate social responsibility is not just

a special program but rather is a part of

an integrated strategy to run business

in a sustainable way. Whether the issues

pertain to the environment, product safety

and impact, or human rights, they are

all part of the long-term thinking that is

characteristic of quality management.

We believe companies that are proactively addressing

these issues today carry less investment risk and are better

positioned to deliver value to their shareholders tomorrow.

Barbara J. Krumsiek

Chief Executive Ofcer,

Calvert Group

B o A R D R o o m B R i E f i N g : C o R p o R A t E S o C i A l R E S p o N S i B i l i t y 2 1

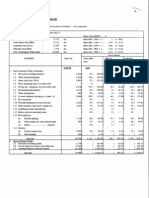

Directors Views: The Value of corporate Social Responsibility programs

Please rank your agreement or disagreement with the following statements, using the scale provided.

Please rank the impact of corporate reputation and philanthropic activities on the following:

Strongly

disagree

Somewhat

disagree

neither

disagree

nor agree

Somewhat

agree

Strongly

agree

n/a

Response

average*

Corporate social responsibility is largely a

public relations issue

41% 25% 10% 16% 8% 0% 2.26

Corporate social responsibility should not be

the purview of the corporation

50% 30% 7% 8% 5% 0% 1.88

Corporate social responsibility is vital to the

proftability of the company

5% 15% 20% 31% 28% 1% 3.62

Corporate social responsibility is assuming a

higher priority at our company

4% 14% 19% 39% 22% 2% 3.63

Corporate social responsibility justifes

sacrifcing short term gain for long term

shareholder and customer value

8% 13% 15% 40% 24% 0% 3.58

Corporate social responsibility is a

fundamental element of modern capitalism

4% 11% 20% 37% 27% 0% 3.74

Companies must do more than the law

requires and a corporate social responsibility

program helps us do that

6% 10% 13% 37% 33% 1% 3.81

Corporate social responsibility is in the best

business interests of our company

2% 2% 9% 33% 53% 1% 4.32

Corporate social responsibility has real,

measurable outcomes

4% 13% 19% 36% 27% 2% 3.69

Corporate social responsibility is mission

critical to our company

9% 14% 28% 24% 24% 1% 3.42

Corporate social responsibility programs help

us attract and retain top talent

5% 10% 16% 39% 28% 1% 3.0

no impact Some impact

Growing

impact

Great impact n/a

Response

average**

Share price 22% 32% 25% 5% 16% 2.14

Employee loyalty 3% 27% 40% 28% 1% 2.95

Customer loyalty 8% 28% 46% 16% 2% 2.70

Partnership/acquisition opportunities 26% 28% 30% 10% 6% 2.25

Insurance and risk mitigation costs 33% 29% 26% 9% 2% 2.11

Corporate litigation costs 34% 32% 23% 8% 4% 2.04

**A higher number indicates greater impact.

*A higher number indicates stronger agreement with the statement.

2 2 B o A R D R o o m B R i E f i N g : C o R p o R A t E S o C i A l R E S p o N S i B i l i t y

How does your board measure your

companys reputation?

Formal surveys and analysis 34.3%

Informally 42.6%

Other 4.1%

(Other responses included: By growth

in revenues and profts. Philanthropy is

important. Social responsibility should

be secondary to the business; feedback

from clients; quantitative risk analysis;

referrals and repeat business; sales and

total number of customers.)

Where does the responsibility for

corporate social responsibility/

philanthropy initiatives reside at your

primary company?

With the board 15.2%

With management 33.3%

With both the board and management 45.0%

Not applicable 5.8%

Other 0.6%

Are corporate social responsibility

and philanthropic programs on your

boards agenda?

Yes, every meeting 7.6%

Yes, at least once a year 21.2%

Yes, irregularly 34.7%

No 30.6%

Not applicable 5.3%

Other 0.6%

What Board Members

Must Know for 2007

Critical Issues

unimportant

Somewhat

important

importamt

extremely

important

n/a

Response

average

To you personally 4% 15% 40% 41% 1% 3.20

To your primary companys board 7% 37% 38% 16% 2% 2.65

Please rank the importance of corporate social responsibility and philanthropy.

50.0%

5.9%

2.4%

Other

43.5%

Yes

Not

applicable

No

Does your company

have a formal corporate

responsibility or

philanthropy program?

(Other responses included:

In development; its an

informal one.)

4.1%

1.2%

9.5%

Yes

86.4%

No

Other

Not

applicable

74.0%

4.1%

21.9%

Yes

Not

applicable

No

Does your company

have a Chief Corporate

Responsibility Ofcer (or

equivalent title)?

Does your company

operate or sponsor a

political action committee

or committees?

*A higher number indicates higher importance.

What Board Members

Must Know for 2007

Advice, Insight and Counsel from Drinker Biddle and Calvert

Critical Issues

2 0 0 7

A s p o n s o r e d s u p p l e m e n t t o

d I r e C t o r s & B o A r d s B o A r d r o o m B r I e f I n g

Legacy Programs and

Director Independence

doug rAY mond

R

ecent changes in the governance landscape

have attacked the often cozy ties between

management and the boardnew proxy rules on

executive compensation, NYSE and NASDAQ listing

standards, and trends in corporate governance which

create structural encouragement for outside directors

to challenge management. Given recent history, this

should not be a surprise.

For example, a majority of the directors of a public

company must be independent, as defned by the

exchanges. Tese independent directors must meet

regularly in executive session withoutand presumably

to discussmanagement. Te audit and executive

compensation committees, which must consist

entirely of independent directors, have increasing

responsibilities, from considering the adequacy of

the Companys internal fnancial controls to the new

CD&A (Compensation Discussion and Analysis) report

required by the SEC.

Te tests for independence that apply to outside

directors generally specifcally focus on fnancial ties.

For example, the defnitions of independence adopted

by the NYSE and the NASDAQ focus on whether a

director has signifcant fnancial or familial ties to the

company, such that he or she might be discouraged from

criticizing management and thereby potentially putting

their renomination (and remuneration) in jeopardy.

Under NYSE rules, a director is not independent if she

or an immediate family member has recently been an

employee of the company, or has received more than

$100,000 in any recent year (other than as director

compensation). Tese fnancial tests have generally

not been applied to charitable contributions made on

behalf of the director. Under NYSE rules, payments to

a charity do not implicate the various fnancial tests of

independence, even if the director has an afliation.

A recent change in proxy rules, as well as a series of

Delaware cases, have heightened the debate on whether

focus on direct fnancial relationships between a director

and the company has been too superfcial to identify the

deeper, and more subtle ways, director autonomy may be

afected. For example, what about the company legacy

program that makes signifcant donations to a charity of

the directors choosing after his or her retirement from

the board? Many people would perhaps be a little cowed

if they thought that the charity might lose that beneft if

they were too challenging of management.

Recognizing this potential, the SEC recently changed

its rules to require that public companies report any

programs by which the company agrees to make

donations to a charity in a directors name, regardless

of when payment is made. Te NYSE also requires

that a listed company report in its proxy statement

any contributions it makes to a charity in which any

independent director serves as an executive ofcer

if, within the preceding three years, contributions in

any single fscal year from the listed company to the

organization exceeded the greater of $1 million, or

2% of such tax exempt organizations consolidated

gross revenues.

In the recent Disney litigation, the court evaluated the

independence of the directors, including the president

of Georgetown University, which was the alma mater

of the CEOs son and recipient of over $1 million in

donations from the CEO. Te Delaware Chancery

court found that these philanthropic and limited

social ties, without more, were insufcient to raise a

doubt as to director independence.

In derivative litigation involving Oracle Corporation,

the court examined the independence of two

directors, both professors at Stanford. Tese two

directors were members of a special committee

deciding whether the company should pursue

certain claims against some other directors and

ofcers. For these purposes, it was essential that the

two directors be independent from the potential

defendants, three of whom also had extensive ties to

Stanford, including being Stanford alumni, signifcant

donors, or current faculty. Te defendant directors

were also considering signifcant future donations

to Stanford. In that case, the court found that these

personal, professional, and philanthropic relations,

taken together, created a reasonable doubt as to the

independence of the special committee.

Despite the numerous regulatory provisions and court

decisions regarding director independence, there are

few bright-line rules outside of the black-and-white

fnancial tests. However, the SECs new disclosure

requirements plainly are designed to deter signifcant

charitable contributions made for or on behalf of a

director. Boards should be sensitive to social and

other relationships among directors, and recognize

increasing criticism that is being directed at what, in

an earlier time, was called the Old Boys Network.

Doug Raymond is a partner in the

law frm Drinker Biddle & Reath

LLP and heads its Corporate and

Securities Group. He can be contacted

at douglas.raymond@dbr.com.

David C. Vaccaro, an associate

in the Corporate and Securities

Group at Drinker Biddle, assisted

in the writing of this article.

Tis article is intended to inform

readers of developments in the

law and to provide information of

general interest. It is not intended

to constitute legal advice regarding

any clients legal problems and

should not be relied upon as such.

Drinker Biddle

& Reath LLP

One Logan Square

18th and Cherry Streets

Philadelphia, PA 19103-6996

(215) 988-2700

(215) 988-2757 fax

www.drinkerbiddle.com

C r I t I C A l I s s u e s 2 0 0 7

Legacy Programs and

Director Independence

DRI NKER BI DDLE

WHERE DI RECTORS LOOK FOR GUI DANCE

PHI LADELPHI A

|

WASHI NGTON

|

SAN FRANCI SCO

CHI CAGO

|

LOS ANGELES

|

NEW YORK

|

FLORHAM PARK

PRI NCETON

|

BERWYN

|

WI LMI NGTON

Drinker Biddle & Reath LLP, a Pennsylvania limited

liability partnership. Est. 1849.

We can help

directors and

significant stockholders

stay on course

in perilous waters.

To find out more, visit us at

www.drinkerbiddle.com.