Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Notable Court Decisions Re

Uploaded by

rhouse_1Original Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Notable Court Decisions Re

Uploaded by

rhouse_1Copyright:

Available Formats

NOTABLE COURT DECISIONS RE: REALTY ISSUES ** Easton v. Strassburger, (1984) 2. Facts: Easton purchased a home from Strassburger.

The home was on an unstable landfill, and had several structural problems that should have been evident to the real estate broker who inspected the land before Easton purchased it. The real estate agents did not have actual knowledge of any problems with the soil, and did not disclose any of the soil problems to Easton. 3. Procedural Posture: Easton sued several defendants in the lower court. The real estate broker is the only one that appealed. The count was one of negligence. 4. Issue: Is a real estate broker, who is employed by the seller, under a duty to disclose facts materially affecting the value of the property which through reasonable diligence should be known to him? 5. Holding: Yes. 6. Reasoning: The court reasoned that a broker had an already established duty to disclose facts actually known to him. Thus, if this rule were not extended to include facts that a reasonable broker should have known, then an ignorant broker could be shielded from liability by his ignorance. This would encourage sloppy inspections. Furthermore, even though the broker is employed by the seller, the buyer typically expects the broker to protect his interests as well. Thus, there is a relationship of trust and confidence. Also, the burden on the brokers could be easily borne. 7. Notes: 1. The same standard of care was rejected for non-residential sales of land in Smith v. Rickard. 2. The Legislature codified the holding of Easton in a narrow manner, requiring the broker of a one to four-family dwelling to conduct a reasonably competent and diligent visual inspection, but not to look in normally inaccessible places. Also, there is a statute of limitations of 2 years to bring an action. ** Drake v. Hosley, (1986) 2. Facts: Drake signed an exclusive listing agreement with Hosley, a broker, to sell some land. The agreement provided for payment of a ten percent commission if, during the period of the listing agreement, 1) Hosley located a buyer "willing and

able to purchase at the terms set by the seller," or 2) the seller entered into a "binding sale" during the term set by the seller. Hosley found some buyers, and all the parties signed a letter of intent to consummate the transaction. However, Drake suddenly wished to have the sale close by April 11 (to satisfy a debt to his wife) and so Drake's lawyer called Hosley to let him know. When the deal was not closed on April 11, Drake sold to another party on April 12 and refused to pay Hosley's commission. 3. Procedural Posture: The lower court granted summary judgment for Hosley, and Drake appeals. 4. Issue: Whether a real estate broker, who has entered into an exclusive sale agreement with the seller, is entitled to payment of a commission even though the sale has not closed, if the broker has located a suitable buyer and the seller then breaches the exclusive agreement. 5. Holding: Yes. 6. Reasoning: The court followed the reasoning in Ellsworth Dobbs, Inc. v. Johnson that a real estate broker does not normally earn a commission unless the contract of sale is performed. This is because it is understood that the money for the payment of a commission will normally come from the sale proceeds. However, the Dobbs court specifically held that the rule only applies in the absence of default by the seller. The court further rejected Drake's argument that the call to Hosley was a modification of the sales contract because Hosley was not employed by the buyers and had no power to act as their agent in a contract modification. 7. Notes: 1. Under the Dobbs rule, the broker can recover from a breaching seller, but there is no provision to recover from a breaching buyer unless that condition is incorporated into the buyer's contract of sale. 2. An broker who contracts with the seller is the primary broker, and if another broker finds a buyer, then the two brokers split the seller's commission 50-50. However, since the broker who found the buyer has some fiduciary responsibility to both parties, it is a conflict of interest. 6. True "buyer's brokers" are faced with a problem in compensation. If the buyer won't agree to pay them a commission directly, then they may be screwed because the seller's broker has no duty to share his commission because the buyer's broker is not acting as his sub-agent. ** Seck v. Foulks, 25 Cal. App. 3d 556 (1972);

2. Facts: Seck was a real estate broker who was an acquaintance of Foulks. Foulks wished to sell some property through Seck, but did not want to make a formal listing. Knowing that he could not collect a commission without a formal writing, Seck jotted down the acreage, price, financing terms, and commission terms on the back of one of his business cards, and then had Foulks initial and date it. During the term of the listing, Foulks observed the work and expense that Seck was expending on the listing, and even referred a potential buyer to him. Seck produced a ready, willing, and able buyer. However, Foulks denies hiring Seck for a commission, and eventually sold to another buyer. 3. Procedural Posture: The lower court found that the business card was insufficient to overcome the statute of frauds writing requirement for the sale of real property. 4. Issue: May a real estate listing contract providing for the payment of a commission to the broker be sufficiently evidenced by the listing, in abbreviated terms, on the back of a business card identifying the property, language of employment, and the initials of the party to be charged? 5. Holding: Yes. 6. Reasoning: The court reasoned that the writing on the back of the business card required factual parol evidence to determine its meaning. Thus, they found that since Foulks had signed the business card and acquiesced in Seck's performance of the listing, that there was sufficient evidence to determine that language of employment (6% comm.) existed on the business card. Seck found a buyer who was ready, willing and able to buy. ** Buckaloo v. Johnson, 14 Cal. 3d 815 (1975); 2. Facts: Buckaloo is a real estate broker who had listed the D.'s property in the past and was very familiar with it. The D. placed a sign saying "For Sale - Contact your Local Broker" on her property. A group of buyers saw the sign and asked Buckaloo about it in his office. He explained the property to them, and asked them to return the next day. When they did not return, Buckaloo sent a letter to the D. stating that he was the "procuring cause" of this particular group of buyers, and if they contacted her directly, to refer them to him. However, Buckaloo ignored the letter and sold to them anyway. 3. Procedural Posture: Buckaloo did not have sufficient evidence to show that he was affirmatively employed by the D. under the statute of frauds in an implied

contract, so he sued under intentional interference with prospective economic gain, a tort. The lower court sustained the D.'s demurrer. 4. Issue: When a broker is the procuring cause of a real estate transaction, and the seller intentionally induces the buyer to avoid the broker, may a cause of action for intentional interference with prospective economic advantage lie even if there is no contract between any of the parties and the broker? 5. Holding: Yes. A cause of action exists when the following elements are pleaded: 1) an economic relationship between the broker and seller or broker and buyer containing the probability of future economic benefit to the broker, 2) knowledge by the seller of the relationship, 3) intent by the seller to disrupt the relationship, 4) actual disruption of the relationship, and 5) damages proximately caused by the seller. 6. Reasoning: The court cited a long string of cases holding that a third party may still be liable for the tort of intentional interference with prospective economic advantage even if the relationship he was interfering with had not attained the status of a formal contract. Although the defense of privilege by the seller due to competition could be forwarded, there would be no policy reason to allow such a defense where the seller is taking advantage of the work already done by the broker to expedite the sale. The sign, in combination with the custom of real estate brokering in the area, established a colorable economic relationship between the seller and the broker with the opportunity to become a fully fledged contract. The D. knew of the relationship between the broker and the buyer because of the letter, and the buyers knew of the relationship between the broker and the seller because of the sign indicating an open listing with all local brokers. Their sole purpose in excluding the agent was to avoid paying of a commission. ** Schwinn v. Griffith, (1981) 2. Facts: An auction was held to sell a piece of property. The D. was the highest bidder. Before the auction was over, but after the gavel fell on his bid, the D. left the auction house, leaving a signed blank check with his daughter to pay for the earnest money. When the seller refused to accept the blank check as payment and contacted the D., the D. refused to pay. The buyer never signed any memorandum of sale. 3. Procedural Posture: The district court dismissed the complaint under the statute of frauds stating that the sale of real estate required a written acceptance by the party to be charged.

4. Issue: May the writing requirement of the statute of frauds be satisfied at an auction by the auctioneer acting as an agent on behalf of the buyer? 5. Holding: Yes. 6. Reasoning: The court held the majority view that the buyer must accept delivery of the purchase agreement signed by the seller for the contract to be binding. However, although the writing was never delivered to or signed by the buyer, the auctioneer, if disinterested in the sale, could become the agent of the buyer at the time the property is "struck off" for the purposes of binding the buyer to the purchase contract. 7. Notes: 1. In some states, the memorandum of sale is prepared directly by the auctioneer, and the parties' signatures are unnecessary. 4. The statute of frauds in the ULTA (uniform land transactions act) requires an 1) an identification of the land, 2) the price or a method of fixing price, 3) is sufficient to indicate with reasonable certainty that a contract to convey has been made between the parties, and 4) the signature of the party to be charged or that party's representative. These rules do not apply if the conveyance is for one year or less, or the buyer has taken possession and paid all or part of the contract price [partial performance], they buyer has accepted a deed, there has been reasonable reliance by the seller, or the party charged admits there is a contract. ** Roundy v. Waner, (1977) 2. Facts: The Roundys are the parents of the Waners. The Roundys executed a warranty deed to the Waners in 1964 so that they could refinance the property in the Waners name. Thus, the Waners held the bare legal title to the property in trust for the Roundys with the understanding that it would be conveyed back upon demand. In 1968, the Waners claim that the Roundys orally agreed to sell the property to them and transfer their beneficial interest in the property in consideration for past kindness, payment of the mortgage and $500 in cash. No formal writing was made. In 1969 the parties had a falling out and the Waners refused to reconvey the property. 3. Procedural Posture: The lower court found that there was an oral contract of purchase made. 4. Issue: May the statute of frauds in real estate transactions be avoided if there is partial performance of the contract?

5. Holding: Yes. 6. Reasoning: The court reasoned that there was substantial evidence of partial performance of the contract. The past consideration included bookkeeping. The Waners bought the Roundys a car for $500. Furthermore, they paid about $7,000 of the mortgage over the years, and made substantial improvements to the house. Such evidence, although possibly arising out of familial affection in normal cases, was "clear and convincing" evidence of a contract in this case. 7. Notes: 5. The partial performance must be "unequivocally referable" to the contract formation. Thus, acts which can be explained by other than contractual inducement are not sufficient to show a contract existed. ** Mahoney v. Tingley, (1975) 2. Facts: The P. and D. entered into an earnest money agreement whereby the D. was to pay a total of $200 of earnest money into escrow. When the time came for the escrow to close, the D. decided not to go through with the deal. There was a clause in the earnest money contract that stated that if the buyer defaulted, the earnest money was to be forfeited as liquidated damages unless the seller elected to enforce the agreement. After the buyer breached, the seller sold to another buyer for $1,250 less and sought to recover the difference from the breaching buyer. 3. Procedural Posture: Unknown. 4. Issue: Whether a seller may recover actual damages from a buyer who breaches an earnest money contract for the sale of real estate, when the earnest money contract allows the seller to elect between specific performance and the buyer's forfeiture of the earnest money as liquidated damages, and when the seller subsequently sells the property to another. 5. Holding: No. 6. Reasoning: The court reasoned that the parties' contract provided for the appropriate remedy. Since the seller had already sold to another, he was precluded from pursuing specific performance. Thus, he was left with liquidated damages only. It must be assumed that the amount of the liquidated damages was negotiated between the parties and that the breaching buyer relied upon the damages clause in assessing his risk of forfeiture. The court rejected the seller's argument that the liquidated damages clause was unenforceable as a penalty [reverse psychology].

The seller may have been able to collect actual damages had the earnest money contract not limited him to liquidated damages. 7. Notes: 2. Although the courts sometimes consider the difficulty in estimation of actual damages, whether a particular liquidated damages clause is enforced depends on whether the contract's consideration contemplated such liquidated damages to be a reasonable pre-estimate of the probable loss. ** Lingsch v. Savage, (1963); 2. Facts: Lingsch bought some real property from a seller who was represented by Savage, who was a real estate broker. Both the seller and Savage knew of substantial problems with the property requiring repair, but did not tell the buyer about them. The purchase contract that they signed included a clause that stated that the buyer was buying the property in "as-is" condition, as well as a clause stating that no representations, guarantees or warranties of any kind were made except what was expressly included in the purchase agreement. 3. Procedural Posture: The lower court sustained the demurrer without leave to amend. 4. Issue: Where a purchase contract for real property states that the property is to be sold as is with no guarantees or representations outside of those expressly indicated in the purchase contract, and both the seller and the seller's agent are aware of material facts that affect the value or desirability of the land, and both are aware that the facts are beyond the ability of the buyer to discover, and neither the seller or his agent disclose such facts to the buyer, may the seller's agent be held liable for fraud upon failure to disclose such facts? 5. Holding: Yes. 6. Reasoning: The court reasoned that fraud included the non-disclosure of material facts by a person under an obligation to disclose them. Furthermore, the agent's representations led the buyer to believe that the absence of disclosure of a particular problem meant that problem was not present. This is true even though the seller's agent has no contractual interest with the buyer because he is a party to the transaction. Although the buyer's pleadings were technically deficient, the court supplemented them. The inclusion of an "as-is" provision does not prevent the contract from being invalidated by fraudulent non- disclosure. Such a provision means that the buyer takes subject to any defect observable to him by reasonable diligence.

** Kriegler v. Eichler Homes, Inc., (1969); 2. Facts: Kriegler owned a residential home that was built by Eichler in 1951. The heating system contained coated steel tubing encased in concrete, instead of the copper tubing normally used due to a copper shortage during the Korean War. Steel tubing is subject to corrosion if not properly installed in the concrete. In 1959, the heating system failed due to corrosion, causing approximately $5,000 of damage to Kriegler's property. The steel was manufactured by General Motors, and installed by Arro, the heating contractors. 3. Procedural Posture: The lower court found that Eichler was liable on a negligence theory of installing the steel tubing. Kriegler did not file a brief to this court, so they reversed as to the negligence issue. Eichler filed a cross-complaint against the heating contractor and General Motors for breach of implied warranty. The lower court found no breach of any warranty. 4. Issue: Is the manufacturer of mass-produced homes subject to strict liability for the damages to property arising from the latent failure of a heating system? 5. Holding: Yes. 6. Reasoning: The court reasoned that the principles of strict products- liability applied to home builders in the same way and for the same reasons that they apply to automobile manufacturers. When a home buyer buys a home, he does not have professional advisors capable of discovering latent defects, nor is he in a position to protect himself contractually against the bargaining power of the builder. It is most efficient to put the loss on the builder who could most easily avoid it. ** Martinez v. Martinez, (1984) 2. Facts: In February 1970, the parents sold land to their son and daughter-in-law under a real estate contract. The children agreed to assume the mortgage, and the parents handed a warranty deed to the children with instructions to deposit the deed in escrow with the bank until the mortgage had been paid in full. However, before delivering the deed to escrow, one of the children had the deed recorded. In 1980, the children defaulted on the mortgage. The parents cured the default and then requested the reconveyance of the property as allowed by the contract. The daughter-in-law refused to reconvey her interest, and the parents brought this action to recover title.

3. Procedural Posture: The trial court found that the parents had intended the warranty deed to be held in escrow until the mortgage had been paid in full. 4. Issue: When the seller hands the deed to the buyer with intent that the buyer put the deed into escrow, and the buyer subsequently records the deed, does this qualify as a legal delivery of the deed? 5. Holding: No. "There is no legal delivery, even where a deed has been physically transferred, when the evidence shows that there was no present intent on the part of the grantor to divest himself of title to the land." 6. Reasoning: The court reasoned that parol evidence was admissible to show that a deed delivered to the grantee was not intended to take effect according to its terms. The intent to transfer title is an essential element of delivery and that intent may be determined from the surrounding circumstances. The fact that the deed was first recorded before deposit in escrow does not create an irrebuttable presumption of delivery. 7. Notes: The physical act of delivery does not matter if the requisite intent is not present. 2. In most states, recording of the deed is not a conclusive presumption of delivery. 3. The rule in Whyddon's Case (1596) states that oral conditions stated by the grantor at the time of delivery of the deed may be disregarded, and title vest immediately in the grantee. ** Wiggill v. Cheney, (1979) 2. Facts: In 1958, Lillian Cheney signed a deed to real property where Flora Cheney was named as the grantee. Thereafter, Lillian put the deed in a sealed envelope and put it in a safe deposit box in the joint names of her and the plaintiff Wiggill. Wiggill was never given the key to the box. Lillian instructed Wiggill that upon her death, he was to go to the box, and deliver the envelope to the addressee, which he did. 3. Procedural Posture: The lower court found that the warranty deed was invalid because of no valid delivery. 4. Issue: For a delivery to be valid, must the grantor divest himself of the possession of the deed or the right to retain it? 5. Holding: Yes.

6. Reasoning: The court reasoned that for the grantor's intent to be established, the deed must "pass beyond the control or domain of the grantor." The grantor may retain the deed if substantial evidence exists that there was a valid delivery with the requisite intention was made, but there were no such facts here. The grantor had the sole and exclusive possession of the deed because she had the only key to the safe deposit box. It would have been easy for her to retract the grant, and that can not be allowed for a valid delivery. 7. Notes: 2. If the grantor had put the deed in a safe deposit box under the joint names of her and the grantee, there probably still would have been no delivery. 3. It is possible to make a present grant of a future interest by the grantor making a properly delivered deed stating that he will retain possession for his life, but the court might interpret that as an intent to make no present grant of any interest. 4. Handing the deed to a third party to be delivered upon the grantor's death (a "death escrow") has been held sufficient to be a proper delivery, with the delivery date relating back to the time the grantor delivered to the third party. This is true even if the deed does not reserve a life estate for the grantor. This is different than the case of delivering to a third party with no condition of death, or directly to the grantee with an oral condition of death. I. Defective Deeds A. Two categories: 1. Void - subsequent bona-fide purchaser loses because the grant was never given effect. 2. Voidable - subsequent bona-fide purchaser wins because the voidable title (acquired by fraud for example) is perfected by the subsequent bona-fide purchase. B. Examples of Void titles: 1. Forgery - a false signature or and addition, deletion or alteration to the language after it has been signed. (The grantor could not have been more careful). 2. "Fraud in factum" - unsuspecting or trusting grantor is told that he is signing something else, or it is slipped in among other papers. 3. Lack of delivery. C. Example of merely Voidable title: 1. Grantee pays for the deed with a bad check or false statements to induce granting. 2. The contents or details of the deed are misrepresented to the grantor. 3. Duress or undue influence.

II. Escrow Closing A. Escrow agent must be a "third" party and not one of the principles. 1. If he is the grantor, there is no delivery because he retains control. 2. If he is the grantee, the delivery is immediate because conditions are ineffective. B. A "true" escrow requires the grantor to deposit the deed without any power to recall it (short of breach by grantee or modification). 1. In a "true" escrow, the delivery relates back to the opening of escrow, and will be effective even if the grantor dies before escrow closes. 2. There must be an underlying enforceable contract of sale. C. Statute of Frauds does not apply to escrow instructions because they do not constitute a contract for the sale of realty. D. An escrow agent occupies a fiduciary responsibility to the parties and will be held liable for negligence or breach of instructions. I. Whitman, Optimizing Land Title Assurance Systems, 42 G. Wash. L. Rev. 40. A. The modern title assurance system consists of 4 subsystems: 1. Data subsystem a. exists to record, retrieve and aggregate data disclosing the legal interests in the property. b. typically operated by lawyers, abstracters and title companies working with public records custodians. 2. Interpretive subsystem a. interprets the data and makes judgments about the current state of the title. b. Lawyers and title insurers usually make these judgments. 3. Risk Allocation subsystem a. allocates risks which result from the existence of legal interests affecting title that outside the data subsystem, as well as errors in the recording and interpreting of the title. 4. Indemnification subsystem a. indemnifies persons whose legal interests are impaired by the risks allocated to them. b. Includes, title insurance, recovery from negligent abstractors or attorneys, and Torrens indemnification funds. B. There are six distinct types of title covenants in deeds: 1. Covenant of Seisin - a promise by the grantor that he owns the land, although not necessarily free from encumbrances.

2. Right to convey - grantor has the right to convey. a. usually overlaps the covenant of seisin, but could be a power of attorney to a third party agent. 3. Against encumbrances - promise that the title is passing free of mortgages, liens, easements, future interests in others, covenants running with the land, etc. a. Since many buyers are willing to take subject to certain beneficial encumbrances, exceptions to this covenant should be spelled out in the deed. 4. Warranty - promise by the grantor to compensate the grantee for losses if the title turns out to be defective or subject to an encumbrance. 5. Quiet enjoyment - same as warranty if the grantee suffers eviction. 6. Further assurances - promise by the grantor to execute such further documents as may arise to perfect title in the grantee. C. Deed covenants vs. Implied covenant of marketability (contractual covenants) 1. Generally, the same sorts of title defects will breach both. 2. Remedies are different a. Deed covenant remedies are usually limited to damages unless the covenant of further assurances can be used to compel specific performance. b. Contract covenants - usual remedy is to rescind before closing, although sometimes can get damages or specific performance. 3. Standard of quality is different a. Implied covenant requires title not only to be good, but also to be marketable, meaning not subject to an unreasonable risk of litigation. b. deed covenants are satisfied by mere good title, even if numerous questions could reasonably be raised about it. D. Present and future covenants 1. Breach of present covenants occurs at the time of deed delivery. a. unknown title defects could arise beyond the statute of limitations. 2. Breach of future covenants occurs at the time of eviction. a. unknown title defects don't start the statute of limitations running until discovery. 3. Future covenants "run with the land." ** Brown v. Lober, (1979)

2. Facts: Brown purchased the land in 1957 from Lober. The deed contained covenants of seisin, right to convey, against encumbrances, warranty and quiet enjoyment. Apparently there was no title search of the mineral rights at the time of conveyance. In 1974, Brown negotiated a contract with Consolidated Coal for the coal rights to the land for $6,000. However, after completing a title search, the Consolidated Coal Company found that the Brown's only held 1/3 title to the coal rights because a prior owner had reserved a 2/3 interest. Thus, Consolidated Coal reduced their price to $2,000. 3. Procedural Posture: Brown brought an action of breach of the covenant of quiet enjoyment against Lober, seeking $4,000 in damages representing the difference between the original sale price and the new sale price of the coal rights. The lower court held that the statute of limitations had run on his claim (wrongly). 4. Issue: Does the mere existence of superior title to unpossessed real property rights breach the covenant of quiet enjoyment? 5. Holding: No. 6. Reasoning: The court first rejected the lower court's holding that the statute of limitations for the covenant of quiet enjoyment begins running at the time of deed delivery. They reasoned that the covenant of quiet enjoyment was not breached because it was merely a promise of uninterrupted possession of the land, not of perfect title. Since no person had yet taken "possession" of the coal by mining it, there had not yet been an eviction. Thus, "until such time as one holding paramount title interferes with the plaintiff's right of possession (e.g. by beginning to mine the coal), there can be no constructive eviction and, therefore, no breach of the covenant of quiet enjoyment." The court refused to let the plaintiffs expand the scope of the covenant of quiet enjoyment to cover the case where it was likely that they would be evicted in the future. 7. Notes: 1. Physical interference by the holder of paramount title with the possession of the grantee will be an actual eviction. However, when the government is the paramount title holder, that fact alone will comprise an eviction, and no further action by the government is necessary. 2. The ULTA requires the vendor to give a deed containing all but the covenants of seisin and further assurances (and in fact implies them) unless the contract expressly provides otherwise. Furthermore, all of the seller's warranties of title run with the land unless expressly reserved. ** Hillsboro Cove, Inc. v. Archibald, (1975)

2. Facts: In 1962, Archibald conveyed parcel B of property to one Weinstock. In 1967, Archibald then conveyed adjacent parcel A to Hillsboro Cove. Hillsboro wished to put condominiums on the parcel A. However, in 1970, it was discovered that a 30 foot strip of the land on parcel A under which Hillsboro wanted to construct condos, was actually owned by Weinstock. In order to secure title, Hillsboro paid out in excess of $52,000 [I assume some of it was to pay off Weinstock]. Parcel A was insured by a title policy issued by Lawyer's Title Guarantee Fund, who were joined as defendants. 3. Procedural Posture: The lower court found that there had been a breach of the covenant of siesin, and awarded Hillsboro $6,000, representing the proportional cost of the disputed 30 foot strip to the amount paid for the whole parcel A [probably determined by simple division of square footage]. Hillsboro contends that it was error not to award him the full amount to his actual damages. 4. Issue: What is the proper measure of damages for breach of the covenant of seizin as to a portion of a parcel of real property? 5. Holding: "The measure of damages is" the cost of clearing title, not to exceed "such fractional part of the whole consideration paid as the value at the time of the purchase of the part to which the title failed bears to the whole block purchased." 6. Reasoning: The court reasoned that the rule was well settled that the proportionate value (not necessarily the square footage) of the disputed piece was to be used in determining the damages. However, the trier of fact could find from the evidence that the value of the 30 ft strip of property at the time of sale was not of any greater value per square foot than the whole. 7. Notes: 1. There is nearly universal agreement that the recovery by the grantee can not exceed the amount of consideration paid. Thus, if the land has appreciated, or if the grantee has made considerable improvements, the grantor does not bear the burden that such investments would not be profitable due to a failure of title. 5. It is usually said that damages for the breach of a covenant against encumbrances are equal to the amount required to remove the encumbrance, if possible, and otherwise diminution in the value of the property. 8. The ULTA gives the buyer the option to rescind the sale for the breach of title covenants up to two years after delivery of the deed. However, she must tender possession and title back to the seller, and pay fair market rent for the time in possession. 10. Estoppel by deed - a doctrine that holds that if A grants a warranty deed to B, but in fact as has no title,

and then later A acquires title from the true owner, that it immediately passes to B. A is estopped from denying that there was a transfer. ** Transamerica Title Ins. Co. v. Green, 11 Cal. 3d 693, 2. Facts: Green was a lawyer and notary public in San Mateo. He notarized a promissory note in favor of Northern Construction, who was insured by Transamerica. The promissory note was secured by two pieces of land; one owned by the Petrakis' as joint tenants, and one owned by the Von Harten's as joint tenants. The promissory note was signed by persons who were introduced to Green as Mr. and Mrs. Petrakis and Von Harten by Green's attorney friend and former partner, Kilday. Kilday had witnessed the persons signing the note and had no reason to believe that they were not who they said they were. However, the persons who represented themselves to be the wives were actually imposters. Following default on the note, Transamerica as trustee caused the two properties to be sold to Northern at a trustee sale. One of the properties was later quitclaimed to Northern for $1,500, and the other given a judgment of quiet title in a surviving spouse. Total damages were $9,600 and Transamerica paid Northern and brought this professional negligence action against Green. 3. Procedural Posture: Transamerica brought an action against Green (and his surety company, General Insurance) for professional negligence under statute in failing to affirmatively identify the signers of the promissory note before notarizing it. The trial court allowed evidence of common practice among local lawyers, in "shortcutting" the statute by taking a lawyer friends word for the persons' identities, to go to the jury. The jury found Green non-liable and Transamerica appeals claiming that the lower court erred in allowing such evidence in a statutory negligence per se action where the issue of negligence was irrebuttable. 4. Issue: Whether a notary public is liable for professional negligence under Cal Civil Code 1185 and Cal Govt. Code 8214 for relying exclusively on the introduction of clients by a trusted third party to determine the client's identities when notarizing the client's signatures. 5. Holding: Yes. "To take an acknowledgment upon such introduction without the oath is negligence sufficient to render the notary liable in case the certificate turns out to be untrue." 6. Reasoning: The court reasoned that the statutes required an affirmative determination by the notary as to the identities of the signers, not just the absence of reason to suspect their identity. The notary has the statutory duty to do so, and

violation of the statute is negligence per se. Although it may have been common practice to do so, the statute forbade relying exclusively upon the introduction by a fellow attorney in determining the identity of the signer. ** McDonald v. Plumb, (1970) 2. Facts: Elizabeth Esterline owned certain real property in L.A. County. In 1960, unknown to Esterline, Singley caused a deed of Esterline's property to be recorded purporting to convey title to Debbas. The grantor's signature was forged but falsely notarized by Plumb, a bonded notary public. Debbas reconveyed the property to Singley who sold it to McDonald. Later a conflict of title naturally arose between McDonald and Esterline. 3. Procedural Posture: Title was quieted in Esterline. The McDonald's sued Singley and Plumb for damages. Judgment for $21,000 plus costs was entered against Singley, but Plumb was found not liable under the theory that the chain of causation was broken during subsequent conveyances, as well as the theory that the McDonald's did not rely directly on Plumb's representations because they were not a party to that conveyance and because they bought title insurance. 4. Issue: Whether the false notarial acknowledgment by a notary public in the chain of title to a grant may be held liable for damages to the grantee when there were intervening grants and when the grantee purchased title insurance. 5. Holding: Yes. 6. Reasoning: The notary was under a statutory duty to all subsequent purchasers to correctly notarize the deed. The court reasoned that the requirement of notarial acknowledgment in real estate transactions is fundamental in preventing fraud. Thus, the intervening fraudulent actions of the grantor did not serve to break the chain of causation, even though the official misconduct of a notary could never be the sole proximate cause of a loss by the grantee. Even though the McDonalds did not directly rely on the false acknowledgment in the original deed, they indirectly did because a clear chain of title is required to establish the record title as of the date of sale that they did actually rely on. I. Theories of Title A. Title theory states 1. Immediately on signing the mortgage the mortgagee (creditor) has right to take possession and collect rents. 2. Rents are part of the security of the loan, but must be applied to

the loan balance if collected by the creditor (on the debtor's behalf) until foreclosure. B. Lien Theory state 1. Creditor has the right to possession only after foreclosure, meanwhile the mortgagor (debtor) has the right of possession and rents. 2. Even here, the debtor may expressly give the mortgagee the right to take possession and collect rents as soon as a default occurs. 3. If the debtor abandons, the creditor may take possession to protect the security of the loan until foreclosure sale. a. In Wheeler v. Community Fed. S&L, the court affirmed punitive damages in a case where the creditor changed the door locks during the winter when the debtor had gone away for a short time, with no intent to abandon. b. Furthermore, if the creditor takes possession, but then does not protect the property from vandalism and waste, he could be held liable for the loss to the debtor (New York and Suburban Fed. S&L v. Sanderman). C. Intermediate states 1. Debtor has the right of possession until the first default, then the creditor has the right of possession. ** Dover Mobile Estates v. Form Products, Inc., (1990) 2. Facts: Fiber Form was the tenant of Old Town properties under a 5 year lease which stated that it was subordinate to any mortgage. Old Town subsequently entered into and defaulted on a second mortgage and the mortgage company foreclosed. Dover bought the property at the foreclosure sale and continued to collect rents from Fiber Form. As Fiber Form's business went bad, they sought to reduce the amount of their rent, and then eventually gave 30 day statutory notice and then vacated the property and stopped paying rent. Fiber Form claimed that the sale terminated their lease and so they were under a month to month lease thereafter. 3. Procedural Posture: The trial court found for Fiber Form and awarded attorney's fees. 4. Issue: Does the foreclosure of a superior mortgage terminate a junior lease to the same property? 5. Holding: Yes.

6. Reasoning: The court reasoned that the lease was made expressly junior to any mortgage by virtue of a subordination clause in the lease. 7. Notes: 1. Normally leases prior to the mortgage are senior and thus not extinguished by foreclosure. However, if the lease contains an option to purchase, it is necessarily junior because otherwise the mortgage would be in danger of being extinguished. Furthermore, in title and intermediate theory mortgage states, the mortgee can demand payment from the senior tenant of rents because of privity of estate when the title passed to him. ** Taylor v. Brennan, (1981) 2. Facts: Taylor bought an apartment complex from Brennan. As part of the sale transaction, Taylor took the property "subject to" a first deed of trust to Brennan's lender in which Brennan had assigned his rentals as security for the loan. Both parties agreed that Taylor would have no personal liability on this first deed of trust, but that he would have the obligation to pay the loan for Brennan. For the remainder of the purchase price, Taylor executed a second deed of trust and assignment of rents in favor of Brennan. The assignment of rents was "in further" security of the second deed of trust. Some time later, Taylor defaulted on two monthly payments to Brennan's original lender, but he was still current with Brennan. Brennan foreclosed the second deed of trust, and took possession and began to collect rents. However, he was not able to collect enough to pay off the default on the first deed of trust and had to come up with an extra $20K. Taylor had collected all the rents up to the point where Brennan foreclosed the second mortgage, but had applied them to other concerns rather than the first mortgage. 3. Procedural Posture: The trial court found that the assignment of rents to Brennan was a "pledge" as security, and found that Taylor was liable for waste of security. The court of appeal affirmed. 4. Issue: Does the assignment of rents as security for a loan give the mortgagee present title to the rents and thus the right to collect rents from the date of execution of the assignment if the assignment states that it is a pledge in further security for the mortgage? 5. Holding: No. 6. Reasoning: The court reasoned that the assignment of rents from Taylor to Brennan was a pledge of future rents that did not give Brennan the right to collect rents and apply them to the mortgage balance until foreclosure. Thus, Taylor was

not liable for waste of security. Quoting Hand in Prudential v. Liberdar for the policy, they stated that it would be contrary to policy to allow a mortgagee to have present title to all rents without taking some action to regain possession or exercise the right to take the rents because the normal understanding is that the mortgagor can collect and keep the rents and mingle them with his other property. 7. Notes: Some states take the position (as did this court) that the mortgagee's title to the rents is perfected upon assignment, but that the right to begin collection requires subsequent action of some minimal kind. Other state that the right to collect rents is perfected upon execution, but that the mortgagee must assign a receiver to collect the rents. A receivership may be assigned by the mortagee instead of taking possession himself because 1) the action of ejectment to take possession takes a long time, 2) the mortgagee doesn't have to deal with the burden of collection of rents, 3) entry by the mortgagee may terminate some favorable leases due to breach of the covenant of quiet enjoyment [resulting in no rent being collectable], and 4) the mortgagee does not submit to the liability. ** Dart v. Western Sav. & Loan Ass'n., (1968) 2. Facts: Dart is the beneficiary of a trust for profits on a trailer park. The trailer park had two outstanding mortgage balances, the first to Western was in the amount of $250K, and the second to Inland was about $55K. Because the trustee, Union, had embezzled funds from the collection of rents on the property that were supposed to have been applied to the mortgages, the first mortgage was about $18,500 in arrears. There was also a $187K federal tax lien on the property. The tax was accruing against the property at about $1700 a year, and interest on the first mortgage was accruing at $1600 a month. The fair market value of the property was somewhere between $500K and $800K. The property was in a state of disrepair, and Dart risked losing the res of the trust. Dart took possession of the property, and collected rents which he used to make repairs, but he did not pay any of the mortgage. Both Western and Inland brought a foreclosure action, and requested the assignment of receivers as was provided by their mortgage contracts. 3. Procedural Posture: The lower court assigned receivers to take possession and collect rents. 4. Issue: Is the assignment of an equitable receiver required when the security interest in the loan is sufficient and not subject to risk of waste? 5. Holding: No.

6. Reasoning: The court reasoned that the fair market value of the property was high enough to cover all of the outstanding obligations. Thus, there was no need to appoint an equitable receiver, even though the mortgage contracts called for it because there was no risk of waste. Since Arizona was a lien theory state, the mortgagor was entitled to possession and rents after foreclosure until the time for redemption had expired. Thus, appointment of a receiver to take possession and collect rents was erroneous. 7. Notes: In American Medical Services v. Mutual Fed. Sav. & Loan, the court stated that a receiver could be appointed when there was a risk of failure to pay taxes and interest. However, the receiver would have limited scope. He could not take possession and collect rents, only accept mortgage payments from the mortgagor on behalf of the mortgagee. 1. In some title states, it is harder to get a receiver than in a lien state because the courts require a showing that the action for ejectment would be insufficient. In most states, inadequacy of the security and insolvency of the mortgagor are not enough to justify a receivership. There must also be some equitable ground such as waste. The broadness of the term "waste" is different among states. 2. Generally, it has been held that where a mortgage document claims that it can cause the assignment of a receiver without regard to the amount of security of the property, the clause has been held to be invalid as being contrary to the discretionary power of the court of equity, however, it might have some evidentiary weight as a prima facie showing that the mortgagee is entitled to a receiver in the absence of a rebuttal. 3. Loans secured by federal funds are subject to receiverships more easily. 4. A receiver may be appointed ex parte, without notice to the mortgagor, pending a foreclosure action. 5. A receiver is generally subject to any special rent agreements that predate the foreclosure, and may not collect higher rents even though they may have been prepaid or less than fair market value. However, the court has the "broad power" to prevent frustration of a receivership by disallowing agreements that were made in collusion with the fraudulent intent of defeating an anticipated receivership. I. Restrictions on transfer by the mortgagor A. Introduction to "Due-on" clauses 1. The due on sale clause enables the mortgagee to accelarate the mortgage debt when a transfer was made without their written consent. a. This prevented the bank from being subjected to more risk. b. Also enabled bank to shed low interest loans when the interest rate market was rising. c. Prevented buyer from qualifying for high rate loans and prevented sellers from offering an assumption of their loan.

2. Due on encumbrance clauses accelerate the debt when the mortgagor takes out a second mortgage, thus reducing his capital interest in the property, and thereby increasing the mortgagee's risk of default. 3. Inreased interest on transfer clauses has the same effect of a due on sale as far as interest rates go, but does not protect the bank from transfer to an uncreditworthy buyer. 4. The triggering event does not need to be an outright sale of the entire property. The FNMA forms accelerate upon transfer of any part of the property or any interest in it. 5. Some courts held these due on sale clauses to be unenforceable unless the lender could show that there was a material change in the risk of the security. B. Legislative response - Garn-St. Germain Depository Institutions Act of 1982 - broadly pre-empting State restrictions on enforcement on dueon-sale clauses. 1. A lender can enter into an enforce a due on sale contract, and all the parties rights and liabilities shall be fixed by the contract. 2. State prohibitions on enforcement on due on sale clauses (if they existed) would only be valid for three more years. 3. For residential purposes, the lender could not enforce the due on sale clause for certain transactions including second mortgages, inheritance, leases, etc. 4. Covers all lenders, all loans. C. Concealment of Transfers 1. In order to avoid the acceleration, mortgagors may attempt to set up a hidden transaction where a buyer makes payments to a third party who pays the mortgage company directly on behalf of the mortgagor (like a wrap-around except secret). 2. This presents problems associated with hidden encumberances and failure to record the transfer. 3. The transferees may have a duty to the mortgagee to disclose a transfer because of the additional risks imposed, thus the lawyer should not get involved in such a transfer because it may be fraudulent. I. Power of Sale Foreclosure A. The deed of trust executed by the mortgagor/trustor and held by the trustee for the benefit of the mortgagee/beneficiary contains a clause authorizing the trustee to execute a foreclosure sale at public auction upon default. 1. Notice requirements vary from state to state, some requiring only a newspaper ad, others requiring mailings to the occupant, owner or personal delivery.

a. Uniform Land Security Interest Act provides more substantial notice requirements to owner-occupants. 2. Normally, no opportunity for judicial proceedings or hearings is given to the owner or any other junior lien holders. a. Federal legislation requires 25 day notice to the government if a federal tax lien exists against the property. 3. The Multifamily Mortgage Foreclosure Act authorizes a non-judicial power of sale foreclosure for federally insured mortgages on other than 1-4 family dwellings, but requires fairly substantial notice and an opportunity for a hearing for the mortgagor to present reasons why the mortgage should not be foreclosed. 4. Avoiding a judicial foreclosure by power of sale has the advantage of less time and money, with the same title result, except the resulting title is less firm because the lack of judicial proceedings may allow certain title defects to go unnoticed. ** Cox v. Helenius, (1985) 2. Facts: Cox owned a home and wanted to build a pool in the back lot. Cox hired San Juan pool company to install the pool, and signed a 10 year installment contract to pay for it. Cox further issued a deed of trust in San Juan's favor to secure payment. Helenius, San Juan's lawyer, was named as trustee. Shortly after installation, the pool pipes collapsed during a backfulsh cleaning, backing sewage up into Cox's home. The Cox's claimed that their damages exceeded the balance due on the note, served notice on San Juan for reconveyance of the note plus damages, and stopped paying the installments. Helenius notified the Cox's that they were in default, scheduled a foreclosure sale, and responded to the Cox's action for damages. After a motion hearing on the Cox's action, Helenius and Cox's attorney discussed settling the case, and Cox's attorney believed that Helenius would not hold the sale. However, the sale was held, and the property, which was worth between $200K and $300K and which had positive equity of at least $100K, was sold for one dollar over the amount outstanding on the San Juan pool contract. 3. Procedural Posture: The trial court entered summary judgment against Helenius as trustee and set aside the deed of trust foreclosure sale. 4. Issue: Does a trustee have a fiduciary responsibility to the mortgagor upon default and foreclosure? 5. Holding: Yes. A trustee is bound to present the sale under every possible advantage to both the debtor and the creditor.

6. Reasoning: The court reasoned that although the Cox's did not comply with the statutory requirement of obtaining an injunction against the sale after they had learned of it, there was still action pending on the obligation secured by the deed of trust, which statutorily precluded foreclosure sale. Furthermore, since Helenius had actual knowledge of the action, he breached his fiduciary responsibility to the Cox's by proceeding with the sale, especially at such a grossy inadequate price. Also, Helenius' actions instilled a sense of reliance in the Cox's that the sale was not going to proceed. They believed that the sale was stayed by the action for damages. The court pointed out the danger of having the trustee, who is supposed to be impartial, be the attorney for the payee. 7. Notes: 1. The trustee has no duty to make an affirmative determination of the state of the debt before proceeding with the foreclosure sale if the payee instructs the trustee that the debt is in default and to proceed. 2. The trustee has no duty to investigate or disclose title defects to the purchaser if they are of record. 3. Normally there are three remedies available to the mortgagor upon foreclosure: 1) an injunction suit against a pending foreclosure, 2) a suit in equity to set aside the sale, and 3) an action for damages against the foreclosing mortgagee or trustee.4. Inadequacy of sale price alone is insufficient to set aside a foreclosure sale, all other things being proper. 5. Some defects of the sale are substantial enough to render it completely void. These include improper acceleration of the debt. However, other defects may only render the title gained in the sale voidable, such as when the mortgagee himself successfully bids on the sale. Such a voidable title could be perfected in a bona fide purachaser without notice for value. I. Anti-Deficiency Legislation A. Prior to 580d, a mortgagee could foreclose a property, then bid a very small price at the foreclosure sale, and then resell at a profit and still go after the debtor for a deficiency judgment on the face value of the note, essentially getting a double recovery at the debtor's expense. B. After 580d, the mortgagee can only bring a deficiency action for the difference between the fair market value of the property and the face value of the debt, and if he does so, the debtor retains his right of redemption to the property. Otherwise, if the mortgagee wants irredeemable title, he can forego the right to a deficiency judgment and sell at a foreclosure sale. Either way, the debtor is protected. ** Brown v. Jensen, (1953); 2. Facts: Brown was the owner of some real property which she sold to Jensen. Part of the purchase price was a secured first deed of trust to Glendale Federal, and

the remainder was carried by Brown as a second. When Jensen defaulted on the first mortgage, Glendale Federal instituted a foreclosure sale at which Brown was not present to protect her interest, and so Glendale purchased the property for the amount outstanding on the first mortgage, thereby extinguishing the second. 3. Procedural Posture: The lower court found for the plaintiff. 4. Issue: Does Cal. Civ. Pro. Code Sec. 580b preclude a mortgagee from collecting a deficiency against a mortgagor in a purchase money mortgage when the mortgagee's security interest in the property has been extinguished by a foreclosure sale of a senior mortgage? 5. Holding: Yes. Undre 580b, for a purchase money mortgage or deed of trust the security alone can be looked to for recovery of the debt. 6. Reasoning: The court reasoned that although section 726 appeared to allow this type of a deficiency action when the security had become valueless, since this was a purchase money agreement, there was the additional obstacle of 580b which was interpreted to mean that in no event shall there be a deficiency judgment whether there is a sale of the property or not. Otherwise, 580b would be redundant with 580d. A person taking a purchase money deed of trust takes the risk that the property will become valueless. This is especially true in second mortgages. 7. Dissent: The dissent reasoned that the majority was stretching the meaning of 580b far beyond its purpose, and that it only applied to deficiency judgments after a foreclosure sale. ** Jones v. Kallman, (1988); 2. Facts: In 1980 Jones bought an apartment building and assumed a $100,000 second mortgage due in Jan 1981. After being transferred overseas, Jones gave Burridge, a licensed broker, power of attorney to refinance the second mortgage. After having trouble finding a willing lender, Burridge contacted another broker, whose salesman was Kallman, to find a lender. Kallman, who was a partner in the brokerage firm, found a lender willing to refinance for an additional year at 21%, and charged a 10% commission, of which he kept 100%. A year later, the loan was again refinanced, and the salesman again kept all of a 10% commission. When Jones returned from overseas, he sued Kallman for ususry claiming that it was not a "broker arranged" transaction as required by the California Constitution. 3. Procedural Posture: The lower court found for the defendant.

4. Issue: Is a real estate loan transaction usurious if arranged by a salesman who is in partnership with a broker, thus giving both persons the benefit of the transaction? 5. Holding: No. 6. Reasoning: The court reasoned that the broker's participation in the transaciton rose to the level of "arranging" the transactions, and that even if he did not receive the commission payments directly, he had a partnership with the salesman and thus derived a benefit from them. Thus, the transaction was "broker arranged" and thus exempt from the usury laws. ** Donovan v. Bachstadt, (1982) 2. Facts: Plaintiff is the buyer of real estate from defendant seller. Seller offered the property at $58,900 with a seller carryback loan of $44,000 at 10 1/2% interest. A purchase agreement was signed, and the seller then could not sell because he lacked marketable title. The buyer bought another house for an unknown price at 13 1/4% interest, and brought suit to recover the difference between the two interest rates as damages. 3. Procedural Posture: The trial court denied recovery stating that the interest rate was only incidental to the purchase. The Court of Appeal reversed stating that the difference in interest rates could be the basis for damages if the buyer entered into a comparable transaction for another home. 4. Issue: What is the proper measure of damages for a seller's breach of a purchase money contract where the seller agreed to finance the buyer at a particular interest rate, and the buyer subsequently buys another house at a different interest rate? 5. Holding: The contract-market differential is the proper measure of damages in a real estate transaction. 6. Reasoning: The court reasoned that neither party was completely right. Compensatory (benefit of the bargain) damages could (and do) apply to purchases of real property where the seller breaches a condition of marketable title. Furthermore, the interest rate on the carry-back loan was in integral part of the bargain. However, when the buyer purchased a separate property, that did not automatically entitle him to the difference in interest rates, because the value of the new property could be different than that of the property involved in the breached purchase agreement. Thus, the proper measure of damages in this case (the

contract market differential) was the difference between the fair market value of a house that could be acquired for a purchase money mortgage of $44,000 at 10 1/2% interest and the purchase price of the first home, $58,000. ** Centex Homes Corp. v. Boag, (1974) 2. Facts: Centex built a condominium complex. Boag signed a purchase agreement for one of the condos, but then was transferred by his company. Boag stopped payment on the earnest money deposit check, and refused to buy the condo. Centex brought this action to compel specific performance of the purchase contract or for liquidated damages in the amount of the deposit in the alternative. 3. Procedural Posture: Unknown. 4. Issue: Is specific performance of a condo purchase contract required upon breach by the buyer when the damages at law are adequate and measureable? 5. Holding: No. 6. Reasoning: The court reasoned that since all the condos were the same, and that there were a fixed number of them, and that they were sold on the basis of a potential buyer viewing the model, then they were not such a special item that monetary damages upon breach could not be measured adequately. Thus, since the equitable remedy of specific performance was only applicable where damages at law were impractical, or immeasureable, this sale had no compelling reason to grant specific performance. ** Century 21 All Western Real Estate and Inv., Inc. v. Webb, (1982) 2. Facts: A Century 21 broker listed Webb's property at $33,000. Subsequently, the salesmen working for the broker made an offer, complete with a purchase agreement to buy the property for $28,000 with seller carry-back financing. After the purchase contract was signed by both parties, it was discovered that an "assignment" of the property had been made to Citicorp to secure a $5,000 loan to Webb. The buyers insisted that Webb clear the Citicorp defect before the close of escrow, apparently thinking that Webb had no right to sell the property (only Citicorp did). Webb insisted that she had previously dislcosed the title defect, and that the buyers, since they insisted on it being cleared, should cure the defect. Apparently, between the downpayment that the buyers made and Webb's own finances, there would not be enough money upon the close of escrow to pay off the encumbrance. Buyers attorney sent a letter to Webb insisting that they were ready

and willing to purchase and that she must immediately tender performance. Closing date of escrow passed at stalemate, and buyers brought this action for specific performance. 3. Procedural Posture: The lower court dismissed the case finding a failure of consideration and a failure of a "meeting of the minds" as to the encumbrance. 4. Issue: May a buyer sue for specific performance of a purchase contract being ready and willing to tender performance himself? 5. Holding: No. 6. Reasoning: The court reasoned that the nature of the encumbrance was unknown to either party. Thus, since the purchase contract made no mention of it specifically, it was not part of the contract. Thus, the buyer had no right to require the seller to clear the encumbrance before the close of escrow. Thus, when the buyers refused to go through with the purchase until it was cleared, they did not perform and did not put Webb into default, especially since the contract did not state that time was of the essence. ** Mattei v. Hopper, (1958); 2. Facts: Mattei was a developer who wished to build on a lot adjacent to Hopper's land. After several attempts to purchase, each of which was refused because they were not for enough money, the seller made an offer which was accepted by Mattei. The offer was reduced to a purchase contract, which contained a clause stating that the purchase was subject to the buyer obtaining satisfactory leases on the neighboring building. After some time, the seller repudiated. The buyer brought this action for specific performance. 3. Procedural Posture: The lower court found that the contract was illusory and failed for lack of mutuality. 4. Issue: Whether the clause making the buyer's performance subject to the acquisition of satisfactory leases rendered the contract void as being illusory. 5. Holding: No. A contract provision making the performance of the buyer subject to the judgment of the buyer is not automatically invalid for lack of mutuality or illusoriness, but rather is a binding contract requiring the buyer to exercise goodfaith in his judgment.

6. Reasoning: The court reasoned that although a reservation of power to one of the parties to determine whether he would perform or not had been held illusory in the past, such reasoning was flawed. The standard of a reasonable person was the appropriate standard to use in determining whether the buyer had exercised goodfaith judgment. ** Smith v. Mady, (1983); 2. Facts: Seller and buyer entered into a purchase contract for the amount of $205,000 for a home. The buyer subsequently breached, and the seller resold the property to a different buyer a few days later for $215,000. The seller brought this action to recover incidental and consequetial damages incurred in upkeep of the property between the time the original escrow was to close and the time of the subsequent sale to the new purchaser. 3. Procedural Posture: The lower court found that the incidental damages were awardable even though the seller had suffered no damage (in fact had a gain) from the second sale. 4. Issue: What is the proper measure of damages upon the breach of a buyer when the seller resells the property at a higher price (and is not a lost-volume seller)? 5. Holding: Contract-market differential. 6. Reasoning: The court reasoned that the seller had not suffered a loss because he was in a better position as a result of the buyer's breach than he would have been had the buyer performed. The extra $10K made probably covered the incidental and consequential damages plus attorney's fees. Thus, no damages were in order. A vendor of real property is not to be placed in a better position at the breaching buyer's expense than he would have had the buyer performed. ** Askari v. R & R Land Co., (1986); 2. Facts: Askari (buyer) and R&R (seller) entered into negotiations through their common broker for the purchase of land for $1.25 million dollars. Buyer offered to place a downpayment, and have the rest financed by a seller's second deed of trust which had interest only payments for 1 year, and then principle and interest payments amortized over 7 years, but due in 5 years. The seller counter offered that all of the P&I should be due in 5 years. Buyer accepted, interpreting that language to mean that no principle or interest was due until the 5 year balloon payment, and then refused to execute escrow instructions that provided for

quarterly P&I payments according to the sellers interpretation of his counter-offer. Shortly after the escrow failed, the buyer filed suit for breach of contract and recorded a lis pendens on the property, which had the practical effect of preventing the seller from mitigating damages in resale due to lack of marketable title. During the ensuing litigation, the buyer claimed that the value of the property went up, and the seller claimed it went down. 3. Procedural Posture: The trial court found that the buyer had breached the contract, and awarded the seller consequential damages which included cost of holding the property, as well as lost interest payments from the buyer. Buyer appeals claiming that he is entitled to offset for appreciation in the property between the time of breach and the time of trial, or in the alternative that he is not liable for any depreciation because the filing of a lis pendens is not a wrongful act, even though it may have prevented resale. Seller appeals asking for additional damages for depreciation during litigation. 4. Issue: What is the proper measure of seller's damages upon a buyer's breach of a purchase contract for real property when the buyer, after breaching, records a lis pendens which prevents the seller from reselling the property to mitigate damages? 5. Holding: The measure of damages suffered by the seller of real property against a defaulting buyer is the excess, if any, of the amount of the contractual sales price over the fair market value at the time of breach, together with any incidental and consequential damages if the seller resells the property, including depreciation of the property caused by the buyer's interference with the resale. 6. Reasoning: The court noted that a seller is entitled to expenses incurred beyond the point of breach to the extent that they were a natural consequence of the breach and that they were reasonably foreseeable at the time of contracting, but only if the seller makes diligent attempts to resell the property. The fact that the lis pendens was absolutely privileged only made a difference in a tort action, not a contract action. Thus, if the lis pendens prevented the buyer from reselling the property, then damages incurred during litigation were proper. These damages could include depreciation of the property, if any. However, since the goal of the damages was to place the seller in the position he would have been in had the buyer not breached, the buyer would be entitled to an offset for any appreciation. Since the trial court had not made express findings of fact as to the seller's diligence, or the value of the property after breach, the case was remanded.

You might also like

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- 1 - Instructions - Enforcement ProcessDocument5 pages1 - Instructions - Enforcement Processrhouse_1No ratings yet

- 0001 When You Are BornDocument3 pages0001 When You Are Bornrhouse_1100% (2)

- DwightAvis-TaxVoluntaryDocument3 pagesDwightAvis-TaxVoluntaryrhouse_1No ratings yet

- 0001 Cheryl Wiker-Affirmation of National-As Amended 05.19.2014 PDFDocument4 pages0001 Cheryl Wiker-Affirmation of National-As Amended 05.19.2014 PDFrhouse_1No ratings yet

- Federalist Papers 15Document1 pageFederalist Papers 15rhouse_1No ratings yet

- William Cooper HOTT Facts Expose of IRS Fraudulent RacketeeringDocument272 pagesWilliam Cooper HOTT Facts Expose of IRS Fraudulent Racketeeringrhouse_1No ratings yet

- Federal Jurisdiction Tax Question AnsweredfedjurisdictionDocument2 pagesFederal Jurisdiction Tax Question Answeredfedjurisdictionrhouse_1No ratings yet

- Federalist Papers 15Document1 pageFederalist Papers 15rhouse_1No ratings yet

- 26 USC6013 GDocument1 page26 USC6013 Grhouse_1No ratings yet

- 0010a Kill Them With Paper WorkDocument21 pages0010a Kill Them With Paper Workrhouse_191% (11)

- Avis Testimony Feb 53Document3 pagesAvis Testimony Feb 53rhouse_1No ratings yet

- Definition VoluntaryDocument1 pageDefinition Voluntaryrhouse_1No ratings yet

- 26CFR1 871-1Document1 page26CFR1 871-1rhouse_1No ratings yet

- 0005c SamplebDocument1 page0005c Samplebrhouse_1No ratings yet

- LegalBasisForTermNRAlien PDFDocument0 pagesLegalBasisForTermNRAlien PDFmatador13thNo ratings yet

- Steps To Terminate IRS 668 Notice of LienDocument10 pagesSteps To Terminate IRS 668 Notice of Lienrhouse_1100% (3)

- Gov Exists in Two FormsDocument2 pagesGov Exists in Two Formsrhouse_1100% (1)

- Eye of The Eagle Volume 1 Number 5Document12 pagesEye of The Eagle Volume 1 Number 5rhouse_1No ratings yet

- CDP Hearing RequestDocument4 pagesCDP Hearing Requestrhouse_1No ratings yet

- 0002a Legisl Intent 16thaDocument3 pages0002a Legisl Intent 16tharhouse_1No ratings yet

- 0005b SampleaDocument1 page0005b Samplearhouse_1No ratings yet

- Modern Money Mechanics ExplainedDocument50 pagesModern Money Mechanics ExplainedHarold AponteNo ratings yet

- First Estate Comprehensive DiagramDocument1 pageFirst Estate Comprehensive Diagramrhouse_1No ratings yet

- Jurisdiction Is The Key FactorDocument6 pagesJurisdiction Is The Key Factorrhouse_1100% (1)

- 0002a Legisl Intent 16thaDocument3 pages0002a Legisl Intent 16tharhouse_1No ratings yet

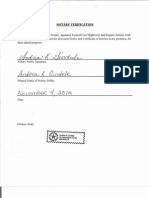

- Notary Verifies SignaturesDocument1 pageNotary Verifies Signaturesrhouse_1No ratings yet

- Power Authority Power PointDocument7 pagesPower Authority Power Pointrhouse_1No ratings yet

- 9b Corp Political Society - PsDocument52 pages9b Corp Political Society - Psrhouse_1No ratings yet

- 9 Natural Order - PsDocument53 pages9 Natural Order - Psrhouse_1100% (1)

- Treatise SovereigntyDocument46 pagesTreatise Sovereignty1 watchman100% (1)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Family Health Nursing Process Part 2Document23 pagesFamily Health Nursing Process Part 2Fatima Ysabelle Marie RuizNo ratings yet

- Q-Win S Se QuickguideDocument22 pagesQ-Win S Se QuickguideAndres DennisNo ratings yet

- Dmat ReportDocument130 pagesDmat ReportparasarawgiNo ratings yet

- Overview of Isopanisad, Text, Anvaya and TranslationDocument7 pagesOverview of Isopanisad, Text, Anvaya and TranslationVidvan Gauranga DasaNo ratings yet

- TRU BRO 4pg-S120675R0 PDFDocument2 pagesTRU BRO 4pg-S120675R0 PDFtomNo ratings yet

- ATS - Contextual Theology SyllabusDocument4 pagesATS - Contextual Theology SyllabusAts ConnectNo ratings yet

- SAP HANA Analytics Training at MAJUDocument1 pageSAP HANA Analytics Training at MAJUXINo ratings yet

- Assignment Chemical Bonding JH Sir-4163 PDFDocument70 pagesAssignment Chemical Bonding JH Sir-4163 PDFAkhilesh AgrawalNo ratings yet

- As 3778.6.3-1992 Measurement of Water Flow in Open Channels Measuring Devices Instruments and Equipment - CalDocument7 pagesAs 3778.6.3-1992 Measurement of Water Flow in Open Channels Measuring Devices Instruments and Equipment - CalSAI Global - APACNo ratings yet

- AnovaDocument26 pagesAnovaMuhammad NasimNo ratings yet

- Group 1 RDL2Document101 pagesGroup 1 RDL2ChristelNo ratings yet

- Radical Acceptance Guided Meditations by Tara Brach PDFDocument3 pagesRadical Acceptance Guided Meditations by Tara Brach PDFQuzzaq SebaNo ratings yet

- Course Outline IST110Document4 pagesCourse Outline IST110zaotrNo ratings yet

- Sample Essay: Qualities of A Good Neighbour 1Document2 pagesSample Essay: Qualities of A Good Neighbour 1Simone Ng100% (1)

- Students Playwriting For Language DevelopmentDocument3 pagesStudents Playwriting For Language DevelopmentSchmetterling TraurigNo ratings yet

- Sample File: Official Game AccessoryDocument6 pagesSample File: Official Game AccessoryJose L GarcíaNo ratings yet

- Net Ionic EquationsDocument8 pagesNet Ionic EquationsCarl Agape DavisNo ratings yet

- United States v. Christopher King, 724 F.2d 253, 1st Cir. (1984)Document9 pagesUnited States v. Christopher King, 724 F.2d 253, 1st Cir. (1984)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 Introduction To Management and OrganisationDocument34 pagesChapter 1 Introduction To Management and Organisationsahil malhotraNo ratings yet

- ME Flowchart 2014 2015Document2 pagesME Flowchart 2014 2015Mario ManciaNo ratings yet

- Module 1 Ba Core 11 LessonsDocument37 pagesModule 1 Ba Core 11 LessonsLolita AlbaNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan 3Document6 pagesLesson Plan 3api-370683519No ratings yet

- 01 Oh OverviewDocument50 pages01 Oh OverviewJaidil YakopNo ratings yet

- De Broglie's Hypothesis: Wave-Particle DualityDocument4 pagesDe Broglie's Hypothesis: Wave-Particle DualityAvinash Singh PatelNo ratings yet

- Vietnamese Grammar Questions and Answers DocumentDocument1 pageVietnamese Grammar Questions and Answers DocumentMinJenNo ratings yet

- A Study of Outdoor Interactional Spaces in High-Rise HousingDocument13 pagesA Study of Outdoor Interactional Spaces in High-Rise HousingRekha TanpureNo ratings yet

- Commonlit Bloody KansasDocument8 pagesCommonlit Bloody Kansasapi-506044294No ratings yet

- Shore Activities and Detachments Under The Command of Secretary of Navy and Chief of Naval OperationsDocument53 pagesShore Activities and Detachments Under The Command of Secretary of Navy and Chief of Naval OperationskarakogluNo ratings yet

- Indian Archaeology 1967 - 68 PDFDocument69 pagesIndian Archaeology 1967 - 68 PDFATHMANATHANNo ratings yet

- Proposal For Funding of Computer Programme (NASS)Document6 pagesProposal For Funding of Computer Programme (NASS)Foster Boateng67% (3)