Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Linda's Filing

Uploaded by

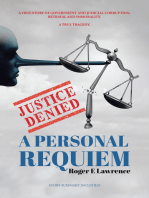

Tami PeppermanOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Linda's Filing

Uploaded by

Tami PeppermanCopyright:

Available Formats

43-109.4. Grandparental visitation rights. A. 1.

Pursuant to the provisions of this section, any grandparent of an unmarried minor child may seek and be granted reasonable visitation rights to the child which visitation rights may be independent of either parent of the child if: a. the district court deems it to be in the best interest of the child pursuant to subsection E of this section, and b. there is a showing of parental unfitness, or the grandparent has rebutted, by clear and convincing evidence, the presumption that the fit parent is acting in the best interests of the child by showing that the child would suffer harm or potential harm without the granting of visitation rights to the grandparent of the child, and c. the intact nuclear family has been disrupted in that one or more of the following conditions has occurred: (1) an action for divorce, separate maintenance or annulment involving the grandchild's parents is pending before the court, and the grandparent had a preexisting relationship with the child that predates the filing of the action for divorce, separate maintenance or annulment, (2) the grandchild's parents are divorced, separated under a judgment of separate maintenance, or have had their marriage annulled, (3) the grandchild's parent who is a child of the grandparent is deceased, and the grandparent had a preexisting relationship with the child that predates the death of the deceased parent unless the death of the mother was due to complications related to the birth of the child, (4) except as otherwise provided in subsection C or D of this section, legal custody of the grandchild has been given to a person other than the grandchild's parent, or the grandchild does not reside in the home of a parent of the child, (5) one of the grandchilds parents has had a felony conviction and been incarcerated in the Department of Corrections and the grandparent had a preexisting relationship

with the child that predates the incarceration, (6) grandparent had custody of the grandchild pursuant to Section 21.3 of this title, whether or not the grandparent had custody under a court order, and there exists a strong, continuous grandparental relationship between the grandparent and the child, (7) the grandchild's parent has deserted the other parent for more than one (1) year and there exists a strong, continuous grandparental relationship between the grandparent and the child, (8) except as otherwise provided in subsection D of this section, the grandchild's parents have never been married, are not residing in the same household and there exists a strong, continuous grandparental relationship between the grandparent and the child, or (9) except as otherwise provided by subsection D of this section, the parental rights of one or both parents of the child have been terminated, and the court determines that there is a strong, continuous relationship between the child and the parent of the person whose parental rights have been terminated. 2. The right of visitation to any grandparent of an unmarried minor child shall be granted only so far as that right is authorized and provided by order of the district court. B. Under no circumstances shall any judge grant the right of visitation to any grandparent if the child is a member of an intact nuclear family and both parents of the child object to the granting of visitation. C. If one natural parent is deceased and the surviving natural parent remarries, any subsequent adoption proceedings shall not terminate any preexisting court-granted grandparental rights belonging to the parents of the deceased natural parent unless the termination of visitation rights is ordered by the court having jurisdiction over the adoption after opportunity to be heard, and the court determines it to be in the best interest of the child. D. 1. If the child has been born out of wedlock and the parental rights of the father of the child have been terminated, the parents of the father of the child shall not have a right of visitation authorized by this section to the child unless:

the father of the child has been judicially determined to be the father of the child, and b. the court determines that a previous grandparental relationship existed between the grandparent and the child. 2. If the child is born out of wedlock and the parental rights of the mother of the child have been terminated, the parents of the mother of the child shall not have a right of visitation authorized by this section to the child unless the court determines that a previous grandparental relationship existed between the grandparent and the child. 3. Except as otherwise provided by this section, the district court shall not grant to any grandparent of an unmarried minor child, visitation rights to that child: a. subsequent to the final order of adoption of the child; provided however, any subsequent adoption proceedings shall not terminate any prior courtgranted grandparental visitation rights unless the termination of visitation rights is ordered by the court after opportunity to be heard and the district court determines it to be in the best interest of the child, or b. if the child had been placed for adoption prior to attaining six (6) months of age. E. 1. In determining the best interest of the minor child, the court shall consider and, if requested, shall make specific findings of fact related to the following factors: a. the needs of and importance to the child for a continuing preexisting relationship with the grandparent and the age and reasonable preference of the child pursuant to Section 113 of Title 43 of the Oklahoma Statutes, b. the willingness of the grandparent or grandparents to encourage a close relationship between the child and the parent or parents, c. the length, quality and intimacy of the preexisting relationship between the child and the grandparent, d. the love, affection and emotional ties existing between the parent and child, e. the motivation and efforts of the grandparent to continue the preexisting relationship with the grandchild, f. the motivation of parent or parents denying visitation, g. the mental and physical health of the grandparent or grandparents,

a.

h. i. j. k. l. m. n. 2. For a.

b. c.

the mental and physical health of the child, the mental and physical health of the parent or parents, whether the child is in a permanent, stable, satisfactory family unit and environment, the moral fitness of the parties, the character and behavior of any other person who resides in or frequents the homes of the parties and such persons interactions with the child, the quantity of visitation time requested and the potential adverse impact the visitation will have on the customary activities of the child, and if both parents are dead, the benefit in maintaining the preexisting relationship. purposes of this subsection: harm or potential harm means a showing that without court-ordered visitation by the grandparent, the childs emotional, mental or physical well-being could reasonably or would be jeopardized, intact nuclear family means a family consisting of the married father and mother of the child, parental unfitness includes, but is not limited to, a showing that a parent of the child or a person residing with the parent: (1) has a chemical or alcohol dependency, for which treatment has not been sought or for which treatment has been unsuccessful, (2) has a history of violent behavior or domestic abuse, (3) has an emotional or mental illness that demonstrably impairs judgment or capacity to recognize reality or to control behavior, (4) has been shown to have failed to provide the child with proper care, guidance and support to the actual detriment of the child. The provisions of this division include, but are not limited to, parental indifference and parental influence on his or her child or lack thereof that exposes such child to unreasonable risk, or (5) demonstrates conduct or condition which renders him or her unable or unwilling to give a child reasonable parental care. Reasonable parental care requires, at a minimum, that the parent provides nurturing

and protection adequate to meet the childs physical, emotional and mental health. The determination of parental unfitness pursuant to this subparagraph shall not be that which is equivalent for the termination of parental rights, and d. preexisting relationship means occurring or existing prior to the filing of the petition for grandparental visitation. F. 1. The district courts are vested with jurisdiction to issue orders granting grandparental visitation rights and to enforce visitation rights, upon the filing of a verified petition for visitation rights or enforcement thereof. Notice as ordered by the court shall be given to the person or parent having custody of the child. The venue of such action shall be in the court where there is an ongoing proceeding that involves the child, or if there is no ongoing proceeding, in the county of the residence of the child or parent. 2. When a grandparent of a child has been granted visitation rights pursuant to this section and those rights are unreasonably denied or otherwise unreasonably interfered with by any parent of the child, the grandparent may file with the court a motion for enforcement of visitation rights. Upon filing of the motion, the court shall set an initial hearing on the motion. At the initial hearing, the court shall direct mediation and set a hearing on the merits of the motion. 3. After completion of any mediation pursuant to paragraph 2 of this subsection, the mediator shall submit the record of mediation termination and a summary of the parties' agreement, if any, to the court. Upon receipt of the record of mediation termination, the court shall enter an order in accordance with the parties' agreement, if any. 4. Notice of a hearing pursuant to paragraph 2 or 3 of this subsection shall be given to the parties at their last-known address or as otherwise ordered by the court, at least ten (10) days prior to the date set by the court for hearing on the motion. Provided, the court may direct a shorter notice period if the court deems such shorter notice period to be appropriate under the circumstances. 5. Appearance at any court hearing pursuant to this subsection shall be a waiver of the notice requirements prior to such hearing. 6. If the court finds that visitation rights of the grandparent have been unreasonably denied or otherwise unreasonably interfered with by the parent, the court shall enter an order providing for one or more of the following: a. a specific visitation schedule,

compensating visitation time for the visitation denied or otherwise interfered with, which time may be of the same type as the visitation denied or otherwise interfered with, including but not limited to holiday, weekday, weekend, summer, and may be at the convenience of the grandparent, c. posting of a bond, either cash or with sufficient sureties, conditioned upon compliance with the order granting visitation rights, or d. assessment of reasonable attorney fees, mediation costs, and court costs to enforce visitation rights against the parent. 7. If the court finds that the motion for enforcement of visitation rights has been unreasonably filed or pursued by the grandparent, the court may assess reasonable attorney fees, mediation costs, and court costs against the grandparent.

b.

TROXEL et vir. v. GRANVILLE

CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME COURT OF WASHINGTON

No. 99138. Argued January 12, 2000Decided June 5, 2000

Washington Rev. Code 26.10.160(3) permits [a]ny person to petition for visitation rights at any time and authorizes state superior courts to grant such rights whenever visitation may serve a childs best interest. Petitioners Troxel petitioned for the right to visit their deceased sons daughters. Respondent Granville, the girls mother, did not oppose all visitation, but objected to the amount sought by the Troxels. The Superior Court ordered more visitation than Granville desired, and she appealed. The State Court of Appeals reversed and dismissed the Troxels petition. In affirming, the State Supreme Court held, inter alia, that 26.10.160(3) unconstitutionally infringes on parents fundamental right to rear their children. Reasoning that the Federal Constitution permits a State to interfere with this right only to prevent harm or potential harm to the child, it found that 26.10.160(3) does not require a threshold showing of harm and sweeps too broadly by permitting any person to petition at any time with the only requirement being that the visitation serve the best interest of the child. Held: The judgment is affirmed. 137 Wash. 2d 1, 969 P.2d 21, affirmed. Justice OConnor, joined by The Chief Justice, Justice Ginsburg, and Justice Breyer, concluded that 26.10.160(3), as applied to Granville and her family, violates her due process right to make decisions concerning the care, custody, and control of her daughters. Pp. 517. (a) The Fourteenth Amendments Due Process Clause has a substantive component that provides heightened protection against government interference with certain fundamental rights and liberty interests, Washington v. Glucksberg, 521 U.S. 702, 720, including parents fundamental right to make decisions concerning the care, custody, and control of their children, see, e.g., Stanley v. Illinois, 405 U.S. 645, 651. Pp. 58. (b) Washingtons breathtakingly broad statute effectively permits a court to disregard and overturn any decision by a fit custodial parent concerning visitation whenever a third party affected by the decision files a visitation petition, based solely on the judges determination of the childs best interest. A parents estimation of the childs best interest is accorded no deference. The State Supreme Court had the opportunity, but declined, to give 26.10.160(3) a narrower reading. A combination of several factors compels the conclusion that 26.10.160(3), as applied here, exceeded the bounds of the Due Process Clause. First, the Troxels did not allege, and no court has found, that Granville was an unfit parent. There is a presumption that fit parents act in their childrens best interests, Parham v. J. R., 442 U.S. 584, 602; there is normally no reason for the State to inject itself into the private realm of the family to further question fit parents ability to make the best decisions regarding their children, see, e.g., Reno v. Flores, 507

U.S. 292, 304. The problem here is not that the Superior Court intervened, but that when it did so, it gave no special weight to Granvilles determination of her daughters best interests. More importantly, that court appears to have applied the opposite presumption, favoring grandparent visitation. In effect, it placed on Granville the burden of disproving that visitation would be in her daughters best interest and thus failed to provide any protection for her fundamental right. The court also gave no weight to Granvilles having assented to visitation even before the filing of the petition or subsequent court intervention. These factors, when considered with the Superior Courts slender findings, show that this case involves nothing more than a simple disagreement between the court and Granville concerning her childrens best interests, and that the visitation order was an unconstitutional infringement on Granvilles right to make decisions regarding the rearing of her children. Pp. 814. (c) Because the instant decision rests on 26.10.160(3)s sweeping breadth and its application here, there is no need to consider the question whether the Due Process Clause requires all nonparental visitation statutes to include a showing of harm or potential harm to the child as a condition precedent to granting visitation or to decide the precise scope of the parental due process right in the visitation context. There is also no reason to remand this case for further proceedings. The visitation order clearly violated the Constitution, and the parties should not be forced into additional litigation that would further burden Granvilles parental right. Pp. 1417. Justice Souter concluded that the Washington Supreme Courts second reason for invalidating its own state statutethat it sweeps too broadly in authorizing any person at any time to request (and a judge to award) visitation rights, subject only to the States particular best-interests standardis consistent with this Courts prior cases. This ends the case, and there is no need to decide whether harm is required or to consider the precise scope of a parents right or its necessary protections. Pp. 15. Justice Thomas agreed that this Courts recognition of a fundamental right of parents to direct their childrens upbringing resolves this case, but concluded that strict scrutiny is the appropriate standard of review to apply to infringements of fundamental rights. Here, the State lacks a compelling interest in second-guessing a fit parents decision regarding visitation with third parties. Pp. 12. OConnor, J., announced the judgment of the Court and delivered an opinion, in which Rehnquist, C. J., and Ginsburg and Breyer, JJ., joined. Souter, J., and Thomas, J., filed opinions concurring in the judgment. Stevens, J., Scalia, J., and Kennedy, J., filed dissenting opinions.

IN THE DISTRICT COURT FOR BRYAN COUNTY STATE OF OKLAHOMA

IN RE THE GUARDIANSHIP OF: #Sierra Sloan , age 12, dob 1/4/2000 Hunter Sloan, age 9, dob 11/8/2002 Harley Sloan, age 9, dob 11/8/2002 Minors Case no.# Judge Admissions Statement

Comes now, Linda Grider to Admit onto Evidence as per Oklahoma Rules of Evidence, a Summary by Dr. Edward S. Stern entitled The Medea Complex: the Mother's Homicidal Wishes to her Child, as read at the Child Psychiatry Section at the Annual Meeting of the Royal Medico-psychological Association at Eastbourne. Part I.Original Articles

The Medea Complex: the Mother's Homicidal Wishes to her Child*

Edward S. Stern, M.A., M.D., M.R.C.P., D.P.M., Medical Superintendent + Author Affiliations

The Central Hospital, Hatton, near Warwick

Summary

The situation in which the mother harbours death wishes to her offspring, usually as a revenge against the father, is described and named the Medea complex. It is shown that there is considerable resistance against admitting these thoughts to the consciousness of the mother or any other person, but that they are of general occurrence. The Medea complex causes many marital difficulties, e.g., dyspareunia, prevention and interruption of pregnancy, failure of breast feeding, and other disordered domestic relations.

It explains such matters as baby farming, disposal to others, and neglect of children, unjust accusations of cruelty to children such as blood libels, and acts of covert and overt cruelty to them.

Footnotes

* A Paper read at the Child Psychiatry Section at the Annual Meeting of the Royal Medico-Psychological Association at Eastbourne

Comes now, Anne House to Admit onto Evidence, as per Texas Rules of Evidence one email from Merry Sloan September 11, 2006, whereby it is in evidence that Merry Sloan 1. Did not have care and custody of Hunter or Harley Sloan 2. that on this date Merry Sloan makes threats Constituting Criminal Coercion, re: a Doctor adopting Hunter and Harley. 4. Merry Sloan admits that when she went to Chris and Anne's house, it was never not clean. 5. Merry Sloan admits in this email that her intent is to have joint custody of the children, although at this time, she had not seen the children for nearly two years, of her own volition.

----- Forwarded Message ---From: Ron Sloan <rons@alliedstoneinc.com> To: carebear2lu@yahoo.com Sent: Mon, May 2, 2011 10:19:48 AM Subject: Mr. Baker I was letting you know that I have released Morrison attorney law office on the intervene of Linda Grider. I do not wish to go against her for Grandparent custody rights I am waving my parental and guardianship rights from Sierra JoAnn Sloan, Harley Rachelle Sloan, and Hunter Lee Sloan In wishing that the courts will give Linda Grider full custody of the three kids.

Ron Sloan Sales Representative Allied Stone, Inc. Office: (580) 931-3388 Cell: (580) 920-3792 Fax: (580) 931-3998 2201 W. Arkansas Durant, Ok 74701

You might also like

- Withdraw of Consent Final Kurt With NameDocument1 pageWithdraw of Consent Final Kurt With NameNateSherman90% (30)

- Evidence of LifeDocument1 pageEvidence of LifeChemtrails Equals Treason100% (9)

- Parental Rights Termination PetitionDocument6 pagesParental Rights Termination PetitionRob M Frazier100% (2)

- Forgiveness and Discharge Estate Dignitary Kurtis Richard 14 BlueDocument1 pageForgiveness and Discharge Estate Dignitary Kurtis Richard 14 BlueTami Pepperman90% (21)

- Forgiveness and Discharge Estate Dignitary Kurtis Richard 14 BlueDocument1 pageForgiveness and Discharge Estate Dignitary Kurtis Richard 14 BlueTami Pepperman90% (21)

- Jonnassen Motion To Show Cause Re JonnassenDocument12 pagesJonnassen Motion To Show Cause Re JonnassenTami Pepperman100% (4)

- 3-25-12 Robb Ryder On Steve Call ForeclosureDocument33 pages3-25-12 Robb Ryder On Steve Call ForeclosureYarod EL100% (4)

- Notice of Mistake Kurtis RichardDocument2 pagesNotice of Mistake Kurtis Richardrifishman1100% (5)

- Writ of Feiri Facias de Bonis EcclesiasticisDocument2 pagesWrit of Feiri Facias de Bonis EcclesiasticisTami Pepperman97% (30)

- Transcript Audios All Tami DaveDocument86 pagesTranscript Audios All Tami DaveTami Pepperman100% (12)

- Executor AppointmentDocument1 pageExecutor AppointmentTami Pepperman75% (4)

- 'Safe Passage' Docs - Support For The DAVID CLARENCE Executor Letter at The Turiya Files PDFDocument1 page'Safe Passage' Docs - Support For The DAVID CLARENCE Executor Letter at The Turiya Files PDF123pratus100% (14)

- Executor AppointmentDocument1 pageExecutor AppointmentTami Pepperman75% (4)

- Executor AppointmentDocument1 pageExecutor AppointmentTami Pepperman75% (4)

- Transcript Part1 TamiAudiosDocument25 pagesTranscript Part1 TamiAudiosTami Pepperman100% (8)

- Karl Lentz Combined Transcripts 11-8-12 To 4-11-15 PDFDocument467 pagesKarl Lentz Combined Transcripts 11-8-12 To 4-11-15 PDFRoakhNo ratings yet

- Template of Adult Deed PollDocument1 pageTemplate of Adult Deed Pollsweemersuper100% (2)

- Asservation For NativityDocument27 pagesAsservation For Nativityjohnadams552266No ratings yet

- Estate Re-Vests To Infant Upon Proof of LifeDocument1 pageEstate Re-Vests To Infant Upon Proof of LifeSue Rhoades92% (12)

- Afterbirth Letter 3Document1 pageAfterbirth Letter 3FAQMD2100% (1)

- Paramount ClaimDocument2 pagesParamount ClaimCurry, William Lawrence III, agent100% (5)

- Waiver of Benefit PriviledgeDocument206 pagesWaiver of Benefit PriviledgeAnonymous 5dtQnfKeTqNo ratings yet

- Presumption of Death PDFDocument15 pagesPresumption of Death PDFAnonymous 5dtQnfKeTqNo ratings yet

- Family Law in Zambia - Chapter 10 - AdoptionDocument8 pagesFamily Law in Zambia - Chapter 10 - AdoptionZoe The PoetNo ratings yet

- NSFD 2021 Application Form and Contract of UndertakingDocument2 pagesNSFD 2021 Application Form and Contract of UndertakingAnny YanongNo ratings yet

- BAMBIC Sent To Cook County IL Legal Notice KNOWLEDGE Re David WesselDocument2 pagesBAMBIC Sent To Cook County IL Legal Notice KNOWLEDGE Re David Wesseltpepperman100% (3)

- Scheulin Email Thread BRENT ROSEDocument3 pagesScheulin Email Thread BRENT ROSEtpepperman100% (1)

- IRS Is 5 Parts and Very Deceptive (Estoppel)Document5 pagesIRS Is 5 Parts and Very Deceptive (Estoppel)liviningdaughter83% (6)

- Debbie Bruscato Letter 01Document7 pagesDebbie Bruscato Letter 01ag maniacNo ratings yet

- Qualified Domestic Relations OrderDocument2 pagesQualified Domestic Relations Ordertpepperman100% (1)

- The Long and Short of It WorddocDocument13 pagesThe Long and Short of It WorddocLoreen50% (2)

- Kurt Kallenbach Peace vs. PeaceableDocument2 pagesKurt Kallenbach Peace vs. PeaceableVen Geancia0% (1)

- USDC 313 CV 052 House of Lords SentDocument249 pagesUSDC 313 CV 052 House of Lords SentRodolfo Becerra100% (2)

- 00 Unconditional ForgivenessDocument1 page00 Unconditional ForgivenessYarod ELNo ratings yet

- JONASSEN ADAM Admissions StatementDocument4 pagesJONASSEN ADAM Admissions Statementsolution4theinnocent100% (2)

- Erbs Void Ab InitioDocument1 pageErbs Void Ab InitiotpeppermanNo ratings yet

- Forgiveness and Discharge Estate Dignitary Kurtis RichardDocument1 pageForgiveness and Discharge Estate Dignitary Kurtis RichardJohnWilliams100% (3)

- Homestead PDFDocument2 pagesHomestead PDFrichard_rowlandNo ratings yet

- 11 15 12karllentz (Episode188)Document9 pages11 15 12karllentz (Episode188)naturalvibesNo ratings yet

- ERBS Motion To Compel Judicial Boundary Abjuration of The RealmDocument1 pageERBS Motion To Compel Judicial Boundary Abjuration of The RealmtpeppermanNo ratings yet

- USUFRUCT and The Parable of The Landowner (MT 21.33-41)Document4 pagesUSUFRUCT and The Parable of The Landowner (MT 21.33-41)Sue Rhoades100% (9)

- Apa Administrative Procedures Act 1946Document51 pagesApa Administrative Procedures Act 1946solution4theinnocent100% (4)

- JONASSEN Motion To Show Cause Re Criminal CoercionDocument2 pagesJONASSEN Motion To Show Cause Re Criminal Coercionsolution4theinnocent100% (4)

- Basadar's Claim of RightDocument16 pagesBasadar's Claim of RightAmbassador: Basadar: Qadar-Shar™, D.D. (h.c.) aka Kevin Carlton George™100% (1)

- Turnabout Docs For CourtDocument23 pagesTurnabout Docs For CourtDUTCH551400100% (5)

- Kurtis Kallanbach Waiving Benefit Public RecordDocument1 pageKurtis Kallanbach Waiving Benefit Public RecordNadah8100% (2)

- Flag Judicial NoticeDocument8 pagesFlag Judicial NoticeCool1No ratings yet

- Security of A NationDocument6 pagesSecurity of A Nationiamsomedude50% (2)

- A Living Woman Traveling On The LandDocument1 pageA Living Woman Traveling On The Landapi-236734154No ratings yet

- Usufructuary Must Give Security (Surety) To OwnerDocument2 pagesUsufructuary Must Give Security (Surety) To OwnerSue Rhoades100% (14)

- Brooks v. Marbury, 24 U.S. 78 (1826)Document15 pagesBrooks v. Marbury, 24 U.S. 78 (1826)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Sweden Parental Responsibilities LegislationDocument9 pagesSweden Parental Responsibilities LegislationzakiNo ratings yet

- Bao V TaoDocument5 pagesBao V TaoRunu YenaNo ratings yet

- Parents Springs From The Exercise of Parental AuthorityDocument2 pagesParents Springs From The Exercise of Parental AuthorityJuan Dela CruzNo ratings yet

- AM-02-11-12 Rule On Provisional Orders Section 1. When Issued, - Upon ReceiptDocument3 pagesAM-02-11-12 Rule On Provisional Orders Section 1. When Issued, - Upon Receiptalexis_beaNo ratings yet

- Seminar 1: By: Mr. Mark Gregor L. UdaundoDocument94 pagesSeminar 1: By: Mr. Mark Gregor L. Udaundoخہف تارئچNo ratings yet

- Family Law - Unit 8 - Custody of ChildrenDocument7 pagesFamily Law - Unit 8 - Custody of ChildrenPsalm KanyemuNo ratings yet

- Notes - Family Code 220-237Document5 pagesNotes - Family Code 220-237Christy Tiu-FuaNo ratings yet

- Experts From TH-WPS OfficeDocument5 pagesExperts From TH-WPS OfficeAnneca LozanoNo ratings yet

- The Family Code of The Philippines: Title Ix Parental AuthorityDocument4 pagesThe Family Code of The Philippines: Title Ix Parental AuthorityMarc Eric Redondo100% (1)

- PFR Assignment Parental AuthorityDocument14 pagesPFR Assignment Parental AuthorityAnnabelle Poniente HertezNo ratings yet

- Adoption Ras and AmDocument24 pagesAdoption Ras and Amvanessa pagharionNo ratings yet

- 2004 Civ Survey DVDocument13 pages2004 Civ Survey DVGabriel FranciscoNo ratings yet

- City of Tampa Case - 1206x1bDocument947 pagesCity of Tampa Case - 1206x1bTami Pepperman100% (4)

- RizalDocument6 pagesRizalelaineNo ratings yet

- Nedlloyd-Lijnen-vs-GlowDocument2 pagesNedlloyd-Lijnen-vs-GlowChap Choy100% (1)

- Republic vs. Lao, G.R. No. 205218Document2 pagesRepublic vs. Lao, G.R. No. 205218DanielMatsunagaNo ratings yet

- Causes & Effects of Terrorism in PakistanDocument21 pagesCauses & Effects of Terrorism in Pakistanabdulmateen01No ratings yet

- Let's Meet Your StrawmanDocument21 pagesLet's Meet Your Strawmanscottyup100% (3)

- Elliot Currie Su Left RealismDocument15 pagesElliot Currie Su Left RealismFranklinBarrientosRamirezNo ratings yet

- Safety Inspection Report and Compliance Inspection: 1. Licensee/Location Inspected: 2. Nrc/Regional OfficeDocument3 pagesSafety Inspection Report and Compliance Inspection: 1. Licensee/Location Inspected: 2. Nrc/Regional OfficeNathan BlockNo ratings yet

- Application To The DeanxxxxxDocument5 pagesApplication To The DeanxxxxxNaimish TripathiNo ratings yet

- Airworthiness Directive Bombardier/Canadair 070404Document8 pagesAirworthiness Directive Bombardier/Canadair 070404bombardierwatchNo ratings yet

- Crime Against WomesDocument110 pagesCrime Against WomesPrajakta PatilNo ratings yet

- Kenya Law - BankruptcyDocument15 pagesKenya Law - BankruptcyFrancis Njihia KaburuNo ratings yet

- Municipality of San Miguel v. FernandezDocument6 pagesMunicipality of San Miguel v. FernandezSheena Reyes-BellenNo ratings yet

- Bayan Muno v. Romulo PDFDocument112 pagesBayan Muno v. Romulo PDFFatzie MendozaNo ratings yet

- Land Bank of The Philippines V Belle CorpDocument2 pagesLand Bank of The Philippines V Belle CorpDan Marco GriarteNo ratings yet

- Regulating Marijuana in CaliforniaDocument32 pagesRegulating Marijuana in CaliforniaSouthern California Public RadioNo ratings yet

- Paper 6: Commercial & Industrial Law and AuditingDocument6 pagesPaper 6: Commercial & Industrial Law and Auditings4sahithNo ratings yet

- Evidence Legal and Trial Technique Syllabus 2017-2018Document17 pagesEvidence Legal and Trial Technique Syllabus 2017-2018Chey DumlaoNo ratings yet

- 1ac v. FirewaterDocument13 pages1ac v. FirewateralkdjsdjaklfdkljNo ratings yet

- Https Nationalskillsregistry - Com Nasscom Pageflows Itp ItpRegistration ITPPrintFormActionDocument1 pageHttps Nationalskillsregistry - Com Nasscom Pageflows Itp ItpRegistration ITPPrintFormActionHemanthkumarKatreddyNo ratings yet

- Shipping 2020 Getting The Deal ThroughDocument14 pagesShipping 2020 Getting The Deal ThroughIvan LimaNo ratings yet

- DBP Vs CA DigestDocument1 pageDBP Vs CA DigestJoms TenezaNo ratings yet

- 01-RnD Chapter 1 P 1-24Document23 pages01-RnD Chapter 1 P 1-24Aditya sharmaNo ratings yet

- G 325a ClarissaDocument2 pagesG 325a ClarissaAnonymous KuAxSCV5cNo ratings yet

- Civil Procedure DigestsDocument277 pagesCivil Procedure DigestsKris NageraNo ratings yet

- Legal Provisions On Cyber StalkingDocument4 pagesLegal Provisions On Cyber StalkingRishabh JainNo ratings yet

- Contracts 2 1030LAW Week 2 OutlineDocument2 pagesContracts 2 1030LAW Week 2 OutlineBrookeNo ratings yet

- Sabiniano Case Folder 5Document2 pagesSabiniano Case Folder 5Eunice Osam RamirezNo ratings yet

- Lakas Atenista Rule 113Document21 pagesLakas Atenista Rule 113lalisa lalisaNo ratings yet

- Bass v. E I DuPont, 4th Cir. (2002)Document8 pagesBass v. E I DuPont, 4th Cir. (2002)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet