Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Rashawn Griffin - Cupcakes in Regalia

Uploaded by

Blair SchulmanOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Rashawn Griffin - Cupcakes in Regalia

Uploaded by

Blair SchulmanCopyright:

Available Formats

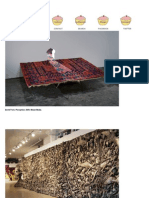

Rashawn Griffin, dumpling, 2012, Mixed media, 87.5 x 107.5 x 84", Courtesy of the Artist.

Rashawn Griffin, a hole-in-the-wall country, installation view.

Rashawn Griffin Makes His Own Rules for Open Exhibition Architecture

Nerman Museum of Contemporary Art Johnson County Community College 12345 College Boulevard 913-469-3000 Overland Park Rashawn Griffin, a hole-in-the-wall country January 13-April 1, 2012

By BLAIR SCHULMAN

At home in the best homes is a pithy phrase uttered by dulcet voices that still linger in the Social Register. Meant to be a compliment, youre supposed to say "thank you," the phrase erects a wall between those on the inside and those who decidedly are not. Rashawn Griffins exhibition at the Nerman Museum presents this ideology that lays bare the clique with a perspective that meanders through childhood and adolescence.

The title, a hole-in-the-wall country at first seems misleading. Viewers might be expecting cowboy portraits and expositional imagery of race relations in the 19th Century Middle West. The exhibits title, says a press statement, derives from the post Civil War autobiography of African American cowboy Nat Love. Instead of real and imagined narrative, Griffin discloses to his audience developmental relations between peers and self, including its disconnections.

The work is reflective of the space's physicality and in its entirety the exhibition feels laconic, with a persistent sense of conceptual indulgence. Through reflection and not reaction, this message becomes clear. Griffin sees an individual's need for belonging and membership in a community, the roots of which are formed early on in life.

Greeting visitors as they climb the stairs to where the exhibition takes place, a 40-foot long pennant bearing the legend Griffin, KS (felt, fabric, wood, 2012) is suspended above. Griffin is not the name of an actual town in Kansas, although for the artist it was a reaction to seeing a similar, albeit smaller pennant, of Volin, South Dakota, a town founded by ancestors of a friend.

Rashawn Griffin, a hole-in-the-wall country, installation view.

If visitors look around carefully and stop to think about it, they will observe a Peter Pan Syndrome in effect. One example, Kashi (mixed media, 2012) is a small, resin coated cutout of cartoon creatures with roofs over their head that seem to fly in space. These cutouts, adolescent in both message and execution, carry the weight of the picture of a childlike appeal of not having one's feet planted on the ground, while reaching for the stars. The works allegories are numerous. In Untitled, (acrylic, ink, water soluble oil on panel, fabric, wood, 2012) swiftly rendered children, helmets and tulips seem to be closely modeled on 1950s-era childrens books.

The small sukkah-like anteroom, dumpling (mixed media, 2012), covered in dizzying argyle fabric, which could be construed as the exhibitions central focus, presents viewers with a personal childlike refuge. On its own, the meaning of this site-specific installation would be difficult to construe. When a similar construction was shown at the Studio Museum in Harlem in 2006, critic Holland

Cotter of the New York Times noted the work doesnt seem to have a particular center, but maybe thats the point. At the Nerman, however, surrounded by other works to allow for a pattern to emerge, it takes root.

To withstand the mostly enclosed rooms harsh lighting and intense patterning requires some stamina. The immediate energy sucks you dry and with its tree-house feel, its easy to imagine needing a secret password to gain entry. Finding the stuffed animals that are cleverly secreted, its like the discovery of a childs long-forgotten favorites under a bed. This piece most strongly manifests Griffins concerns for acknowledgement and belonging.

An artist with international recognition, Griffin has returned home, so to speak to present a hole-in-the-wall country. Born in Los Angeles in 1980 and raised in Olathe, Kansas, he received a Bachelor of Fine Arts from Maryland Institute College of Art in Baltimore, Maryland and a Masters of Fine Arts from Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut. He was an artist in residence at The Studio Museum of Harlem in New York in 2006. After returning to Kansas a few years ago, he splits his time between Kansas City and New York City.

His work is included most notably in The Saatchi Collection, London; the Norton Collection, Los Angeles; The Studio Museum of Harlem in New York; the Nerman Museum of Contemporary Art, Overland Park, as well as several private and public collections.

In a separate gallery, is what Griffin called in his opening night artists talk, Frankenstein compositions. Creating 21 individual pieces, collage elements (thread, sewing needles, graphite, hot glue) are combined with images cut from the Nermans 2009 and 2011 Beyond Bounds catalogues. The original art found in the catalogues is donated by local artists and sold at auction to financially support the museum. Griffin says of these pieces in the same talk, he is stealing the life that goes on around me.

This brings to mind the attitudes about artists reusing imagery, its fair use resulting in adding value (or not) to the original.

For Griffin, reworking images of artists firmly entrenched in a community might be seen as an individuals intent on belonging to a community. Although flat-out mimicry is something a young person would do to ingratiate himself with his peers, I see it as unnecessary in light of everything else he brings to the galleries. Griffin asked his friend Volin to title each piece for him because he wanted the language in the work to reflect the same method of construction I was using for the images; so as there was a limited "palette" I could use in regards to the collages, there too was a limitation in terms of language I could use to describe the images. Volin sent him an online anagram generator. Entering the titles of works to the generator, it would give him back a list of word combinations used to compose new titles.

Rashawn Griffin, untitled, 2012, Water soluble oil, ink, acrylic on panel, 77 x 65", Courtesy of the Artist.

Of the reuse concept, Griffin said in another email, It is an interesting conversation. This stuff gets tricky for me for example, in more than a few museum catalogues and the like, the images of my work (photographed by) institutions are ones that I cannot re-use for reproduction, only because the photographer or the museum have rights to the image as it is in their catalogue for sale to promote the show, despite the fact it is my art.

This series is either an act of community enrichment or a superfluous artistic process, depending on your attitude about reuse. Some artists feel images in the public realm are simply material ripe for the taking. For others, its a violation of individual creation. As a big fan of Pop Art and its roots in appropriation, I enjoy seeing familiar ideas draw new breath. In this setting, however, it feels awkward.

In its desire to express a unifying theme for a hole-in-the-wall country, there is a crisis of economy. This show wants to be spare, but cannot. The support of different paintings, pennants and other ephemera fills the space and creates an experience that drives home this point. How to pare it down, leaving us to arrive at Griffins intentions much sooner, is tricky. I think it can be done if the reworked catalogue images are left for a separate show entirely. Without that obstacle, the idealistic qualities Griffin expresses throughout would feel much clearer in context and intent. In his world of bright colors, patterns, banners, and rooms without doors, Griffin shows us the strict and unwritten rules that need to be observed if trust and entry is to be gained.

Rashawn Griffin, a hole-in-the-wall country, installation view.

Rashawn Griffin, dumpling, 2012, Mixed media, 87.5 x 107.5 x 84", Courtesy of the Artist.

You might also like

- A Tennessee Williams Christmas, Fear and Self-Loathing in The MutilatedDocument4 pagesA Tennessee Williams Christmas, Fear and Self-Loathing in The MutilatedBlair SchulmanNo ratings yet

- Mark Allen: The Spectator As SpectacleDocument2 pagesMark Allen: The Spectator As SpectacleBlair SchulmanNo ratings yet

- Hyperallergic - Reuse ReplenishDocument6 pagesHyperallergic - Reuse ReplenishBlair SchulmanNo ratings yet

- Commentary Amjad Fa UrDocument8 pagesCommentary Amjad Fa UrBlair SchulmanNo ratings yet

- Whitehot Magazine of Contemporary Art - August 2013 - David Ford and The Kansas City Arts RevolutionDocument6 pagesWhitehot Magazine of Contemporary Art - August 2013 - David Ford and The Kansas City Arts RevolutionBlair SchulmanNo ratings yet

- Whitehot Magazine of Contemporary Art - August 2013 - David Ford and The Kansas City Arts RevolutionDocument6 pagesWhitehot Magazine of Contemporary Art - August 2013 - David Ford and The Kansas City Arts RevolutionBlair SchulmanNo ratings yet

- Dali On Display - Huffington PostDocument2 pagesDali On Display - Huffington PostBlair SchulmanNo ratings yet

- Whitehot Magazine of Contemporary Art - August 2013 - David Ford and The Kansas City Arts RevolutionDocument6 pagesWhitehot Magazine of Contemporary Art - August 2013 - David Ford and The Kansas City Arts RevolutionBlair SchulmanNo ratings yet

- The Sweet Life - Ceramics: Art & PerceptionDocument4 pagesThe Sweet Life - Ceramics: Art & PerceptionBlair SchulmanNo ratings yet

- Animals and Buildings Follow Up 030113Document15 pagesAnimals and Buildings Follow Up 030113Blair SchulmanNo ratings yet

- Commentary IngressDocument3 pagesCommentary IngressBlair SchulmanNo ratings yet

- Andrew Jilka at The Invisible Hand GalleryDocument3 pagesAndrew Jilka at The Invisible Hand GalleryBlair SchulmanNo ratings yet

- Commentary Anthony BaabDocument4 pagesCommentary Anthony BaabBlair SchulmanNo ratings yet

- The Collective Consciousness and Installation ArtDocument2 pagesThe Collective Consciousness and Installation ArtBlair SchulmanNo ratings yet

- Jared Flaming New Paintings - JuxtapozDocument2 pagesJared Flaming New Paintings - JuxtapozBlair SchulmanNo ratings yet

- Commentary Sean Star WarsDocument5 pagesCommentary Sean Star WarsBlair SchulmanNo ratings yet

- Quetzlcoatl and The Tree of Life - Review at Mattie Rhodes Art GalleryDocument8 pagesQuetzlcoatl and The Tree of Life - Review at Mattie Rhodes Art GalleryBlair SchulmanNo ratings yet

- Phillip Ahnen Review - Ceramics: Arts & PerceptionDocument4 pagesPhillip Ahnen Review - Ceramics: Arts & PerceptionBlair SchulmanNo ratings yet

- Commentary Now KnowingDocument5 pagesCommentary Now KnowingBlair SchulmanNo ratings yet

- Commentary David Ford 0512Document9 pagesCommentary David Ford 0512Blair SchulmanNo ratings yet

- Phillip Ahnen Review - Ceramics: Arts & PerceptionDocument4 pagesPhillip Ahnen Review - Ceramics: Arts & PerceptionBlair SchulmanNo ratings yet

- Tom Gregg - Cupcakes in RegaliaDocument5 pagesTom Gregg - Cupcakes in RegaliaBlair SchulmanNo ratings yet

- Commentary Judith LevyDocument4 pagesCommentary Judith LevyBlair SchulmanNo ratings yet

- Commentary Sean Star WarsDocument5 pagesCommentary Sean Star WarsBlair SchulmanNo ratings yet

- Commentary Sean Star WarsDocument5 pagesCommentary Sean Star WarsBlair SchulmanNo ratings yet

- Bill Brady GalleryDocument8 pagesBill Brady GalleryBlair SchulmanNo ratings yet

- Phillip Ahnen Review - Ceramics: Arts & PerceptionDocument4 pagesPhillip Ahnen Review - Ceramics: Arts & PerceptionBlair SchulmanNo ratings yet

- Phillip Ahnen Review - Ceramics: Arts & PerceptionDocument4 pagesPhillip Ahnen Review - Ceramics: Arts & PerceptionBlair SchulmanNo ratings yet

- Phillip Ahnen Review - Ceramics: Arts & PerceptionDocument4 pagesPhillip Ahnen Review - Ceramics: Arts & PerceptionBlair SchulmanNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5784)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Noli Me TangereDocument26 pagesNoli Me TangereJocelyn GrandezNo ratings yet

- ALM & Liquidity RiskDocument11 pagesALM & Liquidity RiskPallav PradhanNo ratings yet

- I Am ThirstyDocument2 pagesI Am ThirstyRodney FloresNo ratings yet

- 27793482Document20 pages27793482Asfandyar DurraniNo ratings yet

- Toward A Psychology of Being - MaslowDocument4 pagesToward A Psychology of Being - MaslowstouditisNo ratings yet

- MSA BeijingSyllabus For Whitman DizDocument6 pagesMSA BeijingSyllabus For Whitman DizcbuhksmkNo ratings yet

- Unit 2 Management of EthicsDocument19 pagesUnit 2 Management of Ethics088jay Isamaliya0% (1)

- Cease and Desist DemandDocument2 pagesCease and Desist DemandJeffrey Lu100% (1)

- SFL - Voucher - MOHAMMED IBRAHIM SARWAR SHAIKHDocument1 pageSFL - Voucher - MOHAMMED IBRAHIM SARWAR SHAIKHArbaz KhanNo ratings yet

- Class 3-C Has A SecretttttDocument397 pagesClass 3-C Has A SecretttttTangaka boboNo ratings yet

- Impact of corporate governance on firm performanceDocument4 pagesImpact of corporate governance on firm performancesamiaNo ratings yet

- Green CHMDocument11 pagesGreen CHMShj OunNo ratings yet

- Class: 3 LPH First Term English Test Part One: Reading: A/ Comprehension (07 PTS)Document8 pagesClass: 3 LPH First Term English Test Part One: Reading: A/ Comprehension (07 PTS)DjihedNo ratings yet

- Measat 3 - 3a - 3b at 91.5°E - LyngSatDocument8 pagesMeasat 3 - 3a - 3b at 91.5°E - LyngSatEchoz NhackalsNo ratings yet

- Arvind Goyal Final ProjectDocument78 pagesArvind Goyal Final ProjectSingh GurpreetNo ratings yet

- Boardingpass VijaysinghDocument2 pagesBoardingpass VijaysinghAshish ChauhanNo ratings yet

- A History of Oracle Cards in Relation To The Burning Serpent OracleDocument21 pagesA History of Oracle Cards in Relation To The Burning Serpent OracleGiancarloKindSchmidNo ratings yet

- Proforma Invoice5Document2 pagesProforma Invoice5Akansha ChauhanNo ratings yet

- ACCA F6 Taxation Solved Past PapersDocument235 pagesACCA F6 Taxation Solved Past Paperssaiporg100% (1)

- Static pile load test using kentledge stackDocument2 pagesStatic pile load test using kentledge stackHassan Abdullah100% (1)

- Essential Rabbi Nachman meditation and personal prayerDocument9 pagesEssential Rabbi Nachman meditation and personal prayerrm_pi5282No ratings yet

- The First, First ResponderDocument26 pagesThe First, First ResponderJose Enrique Patron GonzalezNo ratings yet

- Stoddard v. USA - Document No. 2Document2 pagesStoddard v. USA - Document No. 2Justia.comNo ratings yet

- When Technology and Humanity CrossDocument26 pagesWhen Technology and Humanity CrossJenelyn EnjambreNo ratings yet

- Transformation of The Goddess Tara With PDFDocument16 pagesTransformation of The Goddess Tara With PDFJim Weaver100% (1)

- GST English6 2021 2022Document13 pagesGST English6 2021 2022Mariz Bernal HumarangNo ratings yet

- Your Guide To Starting A Small EnterpriseDocument248 pagesYour Guide To Starting A Small Enterprisekleomarlo94% (18)

- Family RelationshipsDocument4 pagesFamily RelationshipsPatricia HastingsNo ratings yet

- Risk Management in Banking SectorDocument7 pagesRisk Management in Banking SectorrohitNo ratings yet

- EVADocument34 pagesEVAMuhammad GulzarNo ratings yet