Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Lessons From Evaluation of World Bank Support For Human Development

Uploaded by

Independent Evaluation GroupOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Lessons From Evaluation of World Bank Support For Human Development

Uploaded by

Independent Evaluation GroupCopyright:

Available Formats

Lessons from Evaluation of World Bank Support to Human Development

Contents

1. Addressing Poverty through Social Safety Nets 2. Learning from Health Reforms: The Experience of Argentina and Brazil 3. Reforming Higher and Technical Education: The Experience of Zambia, Egypt, Jordan, and Yemen 4. Upcoming Evaluations

middle income countries found that their povertytargeted SSNs were not exible enough to increase coverage or benets as needed while low-income countries lacked poverty data and systems to target and deliver benets. Countries that had prepared during stable times by building permanent SSN programs or institutions were better positioned to scale up than those that had not. The Bank was most eective in helping countries in which it had been steadily engaged through lending, Analytical and Advisory Assistance, or dialogue over the decade. Continued emphasis is needed on building SSN systems and institutional capacity, particularly in low-income countries. During the evaluated decade, the Bank began to make an important shift from a focus on projects that emphasize delivery of social assistance benets to helping countries build SSN systems and institutions that can respond to various types of poverty, risk, and vulnerability. The Bank focused its lending, analytical and capacitybuilding support for SSNs signicantly more on middle-income countries (MICs) than on lowincome countries (LICs) throughout the decade, though attention to LICs increased after the crisis

Addressing Poverty through Social Safety Nets

Events of the past decade have underscored the vital need for social safety nets (SSN) - programs designed to protect the poor from shocks and contribute to reducing chronic poverty - in all countries, especially in times of crisis. Over fiscal year 200010, the World Bank supported SSNs with $11.5 billion in lending and an active program of analytical and advisory services and knowledge sharing. IEG has recently evaluated the eectiveness of World Bank-supported SSN programs and found that while Bank support has largely accomplished its stated short-term objectives and helped countries achieve immediate impacts, key areas of Bank support need strengthening. Some of the recommendations and ndings included the following:

The Bank needs to engage consistently during stable times to help countries develop SSNs that address poverty and can respond to shocks. Throughout the decade, countries and the Bank focused SSN support on addressing chronic poverty and human development and less on SSNs to address shocks. The nancial and food crises pointed out weaknesses in countries SSNs, as many

facilitated by trust funding.

Short- and longer-term results frameworks for Bank SSN support need to be strengthened. The Banks support for SSNs has been eective in helping countries reach short-term objectives, such as encouraging poor children to attend school or increasing households short-term consumption; however, these SSN project objectives have not been adequately anchored in longer-term development objectives, such as improving learning and income earning potential. Further effort is needed to ensure strong cross-network coordination of SSNs. Internal World Bank coordination for SSN is challenging due to its multisectoral nature. Sources of tension exist with regard to budget arrangements, task management, and accountability.

it more inclusive and cost-eective. Monitoring and evaluation systems were also strengthened. Short-term education, nutrition, health, and food intake outcome indicators improved for program beneciaries. IEGs impact evaluation found that the program helped increase the likelihood that participant children complete high school and promoted high school completion rates among girls and rural students. The evaluation also found that the test scores of program recipients who graduated from high school were similar to the ones of poor non-recipient graduates. More information can be found in the Project Performance Assessment Report, Colombia Social Safety Net Project, and the Impact Evaluation, Assessing the Long-Term Effects of Conditional Cash Transfers on Human Capital: Evidence from Colombia. In 2005, Ethiopias Productive Safety Net Program (PSNP) was established to provide transfers to the population in chronically food insecure woredas (districts) in a way that prevents asset depletion at the household level and creates assets at the community level. The new safety nets approach focused on tackling chronic or seasonal hunger and sought to provide a more sustainable safety net system compared to the previous emergency appeal system. The Bank supported the PSNP through three Adaptable Program Loans (ALP). Despite the problems associated with implementation, there is strong evidence that the lessons from APL1 have been critical in enabling improvements to be made to the program and to the system of programs that address food insecurity and poverty. The achievement of the objective was demonstrated by the transitioning away from ad hoc annual appeals for emergency food aid towards a more predictably resourced, multi-annual safety net system. A dialogue has emerged recently on what sorts of programming might achieve this. Such a dialogue would not have been possible in 2005 at the start of APL1. There was also progress reversing the upward trend in food insecurity during APL1 although a caseload of more than 7 million remained in the PSNP in 2010 due to population growth and

For more information, please download the study, Social Safety Nets: An Evaluation of World Bank Support, 2000-2010. In the past year, IEG also evaluated SSN projects in Colombia and Ethiopia. In 2005 the World Banks Social Safety Net Project supported the Familias en Accin conditional cash transfer program (CCT) in Colombia to strengthen the countrys safety net. The project set out to consolidate and expand the program and improve the monitoring and evaluation of the countrys safety net portfolio. IEGs project evaluation found that support to the consolidation and expansion of the Familias en Accin helped to quadruple the number of beneciaries, with 45 percent of benets going to the poorest families. Consistent with needs, most of the benets went to pre-school children and secondary school students. Due to diculties with scale-up in urban areas uptake rates were lower than expected and compliance with health and education co-responsibilities did not reach its targets. Crucial second generation issues (such as (i) modication of the education benets to emphasize secondary school incentives in large urban areas, as recommended by impact evaluations; (ii) incorporation of information technologies to reduce transaction costs) were addressed, contributing to the consolidation of the CCT program by making

ieg.worldbankgroup.org ieg.worldbankgroup.org

the impacts of food price shocks in 2008. Above all, the PSNP demonstrates what can be achieved in a low-income country with limited capacity and high levels of poverty. For more information, download the Project Performance Assessment Report, Ethiopia Productive Safety Net Project.

the three operations have introduced innovative nancing features and health care reforms, it is equally important to highlight the support these operations gave to strengthening monitoring and evaluation of patient-level data, and the building up of skills and institutional support, which contributed to the sustainability of the reforms. In Brazil, comparative studies found better quality of care in family medicine than in the traditional primary care model. Municipalities could win a bonus and performance price if they improved health administration and nancial management and made progress in family medicine implementation. Overtime, participating municipalities substantially improved their management performance as well as their family medicine coverage rates. Although Brazil did not add a nancial incentive to the payment of providers, the use of health services in family medicine centers increased. In Argentina, the SECAL supported policy actions and protected the nancing for essential health programs during times of economic crisis. Consequently, use of these programs remained high and increased, including such services as directly-observed treatment, short course (DOTS) for TB and treatment for the prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV. At the same time, the APL1 in Argentina contributed to

Learning from Health Reforms: The Experience of Argentina and Brazil

IEG conducted a project performance assessment on three health operations including a Sector Adjustment Loan (SECAL) in Argentina, and two rstphases of multiple-years APL1 in Brazil and Argentina. All three operations assisted the governments in developing reforms at the primary health care (PHC) level and disbursed earmarked funds for reforms to supplement the existing government budget. These operations also introduced nancial incentives to the health sector to change the incentive framework and reward health authorities and sta for better results. In Argentina, the SECAL and the APL1 helped fund implementation of the key reform package, namely the Maternal and Child Health Insurance Program, which contains a supply-side subsidy to PHC providers. In Brazil, the APL1 supported the Government Conversion Program, which reorganized traditional PHC into family medicine facilities. While

improved quality of care by increasing the nancial resources available for basic care and by training a large number of medical sta in the adherence to 80 treatment protocols. The scal transfer to the provinces was linked to Maternal and Child Health Insurance Program enrollment and results achieved in ten health indicators The performance of ten relevant basic health indicators increased substantially over the project time. Some of the lessons learned from the assessment were:

Pooling World Bank and government funds can build capacity in governance, but also increase transaction costs for governments. Depending on the country context, institutional and governance adjustments may be needed. If municipalities are the nal recipients of pooled funds, administrative sta may need training in planning and budgeting to be able to plan, access, and implement funds in a timely manner.

Reforming Higher and Technical Education: The Experience of Zambia, Reliable information systems, analysis, and independent concurrent audits are prerequisites Egypt, Jordan, and Yemen

for allocating resources based on population needs and service use.

Following policy-based lending with an APL program can help the government stay on the course of the reform.

To learn more, download the Project Performance Assessment Report, Results-Based Health Programs in Argentina and Brazil.

Strategic and substantial upfront investments are needed if a country plans to modify the incentive system in health to stimulate better sector performance. These comprise investment in data analysis and reporting of results back to providers; provider readiness including sta training and possibly recruitment of additional sta ; institutional capacity building in budget and nancial management; and management capacity of the health system. In the case of Argentina, the provinces had to invest in detailed data collection and analysis to show their progress towards targets. To ensure the accuracy of the data, results were audited by an independent private audit rm and provinces and providers were ned for incorrect data reporting. There is a need for strong collaboration with local governments and providers to ensure timely information transfer to dene payment and implementation of corrective measures to improve results. This is important to ensure the eectiveness of linking disbursement from the center to provinces to results in decentralized health systems and for central governments to receive the relevant information from local levels on the use of funds.

The Zambia Technical Education, Vocational and Entrepreneurship Training Development Support Program, implemented between 2002 and 2008, aimed to comprehensively reform Zambias Technical Education, Vocational and Entrepreneurship Training (TVET) system. The changes were made through granting nancial and managerial autonomy to the publicly-owned training institutions; establishing an autonomous national training authority (TEVETA) responsible for regulation and quality assurance; nancing training in all types of institutions through a competitive fund (TEVET Fund); and diversifying sources of funding through cost recovery (student fees) and a proposed payroll levy on enterprises. The implementation authority for TVET would be shifted from the central government to the new training authority and training institutions, with the central ministry focusing upon policy formulation and information management. The Training Development Support Program made considerable progress towards raising the quality of the system, with the new quality assurance and curriculum development procedures implemented by TEVETA, which can be expected to improve the quality of training. Improvements were also made in increasing the demand orientation of training, by involving industry experts through TEVETA in setting

standards, reviewing curricula, and developing modular and in-service training capacity. However, strengthening the inuence of the private sector through local management boards of training institutions, and the channeling of government and private nance for training through the TEVET Fund, were not successfully accomplished. After some delay, management boards were established, but they had limited authority and did not have an important role. Moreover, the TEVET Fund was briey piloted with donor funding, without a contribution from the government or private sector. Zambias experience in attempting to shift its TVET system from supply- to demand-driven provides several lessons.

Reforms of TVET should be based on indepth analysis of the strengths, perceptions, interests, and incentives of different stakeholder groups, since change in the governance structure of TVET needs buy-in by multiple stakeholders. Implementation of the project was substantially aected by insucient consensus and willingness to cooperate between the various parties involved in implementation. A competitive training fund under nongovernment management can be eective in addressing needs in the informal sector and the needs for in-service training, but sustainability is a major challenge. Payroll levies to finance in-service training are difficult to apply in low-income countries as well as in the informal sector.

For additional lessons learned, download the Project Performance Assessment Report, Zambia Technical Education Vocational and Entrepreneurship Training Development Support Program. In the Middle East and North Africa Region, IEG assessed the performance of three higher Education Projects in Egypt, Yemen, and the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan. The projects had the objectives of improving the quality, eciency,

supported reforms motivated by the World Bankendorsed Higher Education Reform Model, which includes university autonomy with accountability, quality assurance, and accreditation; transparent nancing; competition for research funds; increased use of Information Communication Technologies (ICT) for teaching; dierentiated missions; diversied nance; cost recovery; and overall system coordination and oversight. Five of these features were adopted and relatively well implemented in Egypt and Jordan, namely quality assurance; competition for research/ development funds; increased use of ICT; dierentiated missions (less well implemented in Jordan); and overall system coordination (less well implemented in Jordan). None of the features incorporated in Yemens Higher Education Project were implemented fully successfully, but there were some parts of the model not included in the Bank-supported Yemen project that were successfully instituted in the country during the project period (competition for funds; dierentiated missions; cost recovery). Features such as formula nancing and university autonomy met with resistance in all three countries. The three projects were most focused and successful at creating inputs or immediate conditions (drawing from the higher education reform model) for improved quality. However, data was not collected in any of the countries to measure whether these inputs and outputs have made a dierence in terms of student outcomes such as improved learning and/or better preparation for the labor market. Egypt, Yemen, and Jordans experiences provide lessons for other countries attempting to reform their higher education system:

decision-making is not sufficient on its own to ensure that the reforms will result in more employable graduates. Instead, higher education systems need to systematically monitor the labor market relevance of their oerings and the success of their graduates.

Efforts to enhance the quality of higher education must focus on improving learning outcomes, which implies the need for standardized assessments of student achievement. Decreasing graduate unemployment requires serious gate-keeping by the government, shifting enrollments away from overloaded elds, and more serious incentive structures to study in needed elds.

For more information, download the Project Performance Assessment Report, Higher Education Reform in the Middle East and North Africa: An IEG Review of the Performance of Three Projects. IEG recently assessed the experience of two education projects in Jordan: the Jordan Higher Education Development Project and Education Reform for Knowledge Economy I Program. The Higher Education Development Project was implemented from 2000 to 2007 and aimed to improve higher education quality, relevance, and eciency by investing in ICT, scientic equipment, and faculty training needed to upgrade university academic programs and management information systems. The project also attempted to reform education sector governance by strengthening recently created governance structures such as the Higher Education Accreditation Council for quality assurance and the Higher Education Council for overall policy making. Additionally, the project had a goal of improving links to the labor market by reforming the system of community colleges under the oversight of Al Balqa Applied University (BAU). The project accomplished the building of systems that can contribute to better management through improved ICT. Some improvements in quality resulted from the provision of much-needed ICT equipment for teaching and learning and some changes in teaching methods. However, the reforms of governance fell short

The introduction of a widely adopted change model needs to be preceded by sufficient sector analytic work to create an appreciation of the complexities and implications of the proposed changes and of the likely sources of resistance. Such analysis could help determine the parts of the model that are appropriate to the context and the pace of adoption. Restructuring of higher education courses and programs and private sector participation in

ieg.worldbankgroup.org

Higher education curricula need to continue adapting to the new secondary graduates while the admission procedures for higher education need to adapt to the criteria of the knowledge economy. The higher education system can do more to improve quality and relevance, including becoming actively linked in real time with the labor market and economy. More upto-date labor market information is needed as well as more private sector representation in the governance of universities and community colleges.

of most of their objectives. The formula for funding recurrent budgets was not implemented due to political and technical constraints. The competitive fund for new academic programs only became fully competitive near the end of the project, and the reforms of the community colleges under the oversight of BAU to improve labor market relevance were not completed. The Education Reform for Knowledge Economy Program was implemented from 2003 to 2009 and aimed to improve the quality, relevance, and eciency of early childhood, basic, and secondary school education systems by developing a new comprehensive vision and strategy for basic and secondary education, developing new curricula, training teachers, upgrading the learning environment in schools, and promoting early childhood education. By the end of the project, 80 percent of Jordans schools were connected to the Internet, and almost all schools had at least basic ICT equipment. Moreover, performance on learning assessments showed improvement from the new curricula, learning materials, and teacher training. Jordans experience indicates that the following lessons:

For more information, download the Project Performance Assessment Report, Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan Higher Education Development Project and Education Reform for Knowledge Economy I Program.

Upcoming evaluations

IEG is in the process of evaluating the World Banks Support for Youth Employment over FY 2001-2011. Youth employment has become a major and costly issue in many countries. Young people encounter more diculties than adults in nding quality work or becoming self-employed. In many countries, females entering the labor force face more social and labor market entry barriers than men. Instead of contributing to the economy, the young who are underemployed or unemployed, incur costs to the economy. This evaluation will identify what the World Bank is doing to promote youth employment, showcasing the international evidence on initiatives to promote youth employment and draw lessons emerging from the Banks support in helping countries increase employment of young workers. The evaluation report is due in summer 2012. IEG is nalizing an evaluation of the World Bank Groups Response to the Global Economic Crisis: Phase II. In addition to scal and nancial sector support, the report analyzes the Banks social protection response. The global crisis came on the heels of food and fuel price crises with which poor and vulnerable households had already had to cope.

The complexity of education reform requires sustained effort beyond the standard five-year project cycle. The emphasis on critical thinking and creative problem-solving at each level means that some mutual adjustments are needed.

It is estimated that the crisis increased the worlds poor by an additional 53 million people in 2009. Consequences of the crisis for households were typically threefold: fewer jobs and lower earnings, lower remittances, and reduced access to basic social services. The aim of IEGs real-time evaluation is to assess how relevant and eective the Bank has been in helping countries use, scale up, and develop their social protection programs and policies to protect households and workers from the shocks of the global economic crisis. The evaluation report is due in fall 2011.

IEG is currently elding a project performance assessment on Technical and Higher Education in Colombia, Chile, and India to help inform the Youth Employment evaluation. Findings and lessons from the evaluation of these projects will be available by June 2012.

For more information, visit the IEG webpage at http://ieg.worldbankgroup.org

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Filipino Exam AnalysisDocument22 pagesFilipino Exam AnalysisGasco Eyen Aquino75% (16)

- Pa CertificationDocument2 pagesPa Certificationapi-253504218No ratings yet

- Blind Side Movie DiscussionDocument5 pagesBlind Side Movie Discussionapi-309054390No ratings yet

- Post Observation ReflectionDocument2 pagesPost Observation Reflectionapi-314941135100% (2)

- Internship Agreement and PolicyDocument5 pagesInternship Agreement and PolicyPrateek SinghNo ratings yet

- Assessing The Monitoring and Evaluation Systems of IFC and MIGA Biennial Report On Operations EvaluationDocument158 pagesAssessing The Monitoring and Evaluation Systems of IFC and MIGA Biennial Report On Operations EvaluationIndependent Evaluation GroupNo ratings yet

- CLEARInitiative Web Producer-Aug2012Document2 pagesCLEARInitiative Web Producer-Aug2012Independent Evaluation GroupNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of World Bank Group Assistance To Low-Income Fragile and Conflict-Affected StatesDocument189 pagesEvaluation of World Bank Group Assistance To Low-Income Fragile and Conflict-Affected StatesIndependent Evaluation GroupNo ratings yet

- Managing Forest Resources For Sustainable Development An Evaluation of World Bank Group ExperienceDocument219 pagesManaging Forest Resources For Sustainable Development An Evaluation of World Bank Group ExperienceIndependent Evaluation Group100% (1)

- Director Position Available at The Centre For Learning On Evaluation and Results, University of WitwatersrandDocument2 pagesDirector Position Available at The Centre For Learning On Evaluation and Results, University of WitwatersrandIndependent Evaluation GroupNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of World Bank Group's Strate in LiberiaDocument218 pagesEvaluation of World Bank Group's Strate in LiberiaIndependent Evaluation GroupNo ratings yet

- The World Bank Group and The Global Food Crisis An Evaluation of The World Bank Group ResponseDocument212 pagesThe World Bank Group and The Global Food Crisis An Evaluation of The World Bank Group ResponseIndependent Evaluation GroupNo ratings yet

- Improving Institutional Capability and Financial Viability To Sustain Transport An Evaluation of World Bank Group Support Since 2002Document172 pagesImproving Institutional Capability and Financial Viability To Sustain Transport An Evaluation of World Bank Group Support Since 2002Independent Evaluation GroupNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of The International Finance Corporation's Global Trade Finance Program, 2006-12Document157 pagesEvaluation of The International Finance Corporation's Global Trade Finance Program, 2006-12Independent Evaluation GroupNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of The World Bank Group Program in AfghanistanDocument287 pagesEvaluation of The World Bank Group Program in AfghanistanIndependent Evaluation GroupNo ratings yet

- Evaluation Lessons From World Bank Group's Work in Water, Transportation and EnergyDocument4 pagesEvaluation Lessons From World Bank Group's Work in Water, Transportation and EnergyIndependent Evaluation GroupNo ratings yet

- The Matrix System at Work: An Evaluation of The World Bank's Organizational EffectivenessDocument286 pagesThe Matrix System at Work: An Evaluation of The World Bank's Organizational EffectivenessIndependent Evaluation GroupNo ratings yet

- IEG Organizational Chart - 01!11!2012Document1 pageIEG Organizational Chart - 01!11!2012Independent Evaluation GroupNo ratings yet

- Risk Management at The World Bank Group: What Evaluations Tell UsDocument3 pagesRisk Management at The World Bank Group: What Evaluations Tell UsIndependent Evaluation GroupNo ratings yet

- Adapting To Climate Change: Assessing World Bank Group ExperienceDocument193 pagesAdapting To Climate Change: Assessing World Bank Group ExperienceIndependent Evaluation GroupNo ratings yet

- Youth Employment Programs: An Evaluation of World Bank and IFC SupportDocument206 pagesYouth Employment Programs: An Evaluation of World Bank and IFC SupportIndependent Evaluation GroupNo ratings yet

- Capturing Technology For Development: An Evaluation of World Bank Group Activities in Information and Communication TechnologiesDocument158 pagesCapturing Technology For Development: An Evaluation of World Bank Group Activities in Information and Communication TechnologiesIndependent Evaluation GroupNo ratings yet

- TOR Information Management Analyst April2 2012Document2 pagesTOR Information Management Analyst April2 2012Independent Evaluation GroupNo ratings yet

- Assessing IFC's Poverty Focus and ResultsDocument114 pagesAssessing IFC's Poverty Focus and ResultsIndependent Evaluation GroupNo ratings yet

- Lessons From Evaluations: World Bank Group Support To Human Development (Issue 3)Document8 pagesLessons From Evaluations: World Bank Group Support To Human Development (Issue 3)Independent Evaluation GroupNo ratings yet

- World Bank Group Response To The Global Economic Crisis (Phase II)Document358 pagesWorld Bank Group Response To The Global Economic Crisis (Phase II)Independent Evaluation GroupNo ratings yet

- Doing Business: An Independent Evaluation. Taking The Measure of The World Bank-IFC Business IndicatorsDocument122 pagesDoing Business: An Independent Evaluation. Taking The Measure of The World Bank-IFC Business IndicatorsIndependent Evaluation GroupNo ratings yet

- The Africa Act Plan: An IEG EvaluationDocument181 pagesThe Africa Act Plan: An IEG EvaluationIndependent Evaluation GroupNo ratings yet

- World Bank Support To Education Since 2001Document133 pagesWorld Bank Support To Education Since 2001Independent Evaluation GroupNo ratings yet

- Safeguards and Sustainability Policies in A Changing World - An Independent Evalaution of World Bank Group ExperienceDocument192 pagesSafeguards and Sustainability Policies in A Changing World - An Independent Evalaution of World Bank Group ExperienceIndependent Evaluation GroupNo ratings yet

- Analyzing The Effects of Policy Reform On The PoorDocument113 pagesAnalyzing The Effects of Policy Reform On The PoorIndependent Evaluation GroupNo ratings yet

- The Quality of Growth: Fiscal Policies For Better ResultsDocument135 pagesThe Quality of Growth: Fiscal Policies For Better ResultsIndependent Evaluation GroupNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of World Bank Engagement at The State LevelDocument136 pagesEvaluation of World Bank Engagement at The State LevelIndependent Evaluation GroupNo ratings yet

- Instructional Planning for Differentiating Reality from FantasyDocument4 pagesInstructional Planning for Differentiating Reality from FantasyCarine Ghie Omaña EncioNo ratings yet

- Kate McDowell - CVDocument4 pagesKate McDowell - CVKate McdowellNo ratings yet

- Sop Report FinalDocument4 pagesSop Report FinalnghanieyNo ratings yet

- Circulatory System ProjectDocument6 pagesCirculatory System ProjectPak RisNo ratings yet

- JSS 2016053009190527Document105 pagesJSS 2016053009190527ushaNo ratings yet

- Myla Celino Bayas: Personal DataDocument4 pagesMyla Celino Bayas: Personal DataMaribeth BenguetNo ratings yet

- ENGL 1101 SyllabusDocument6 pagesENGL 1101 SyllabusjeekbergNo ratings yet

- Algebra One Lesson 7.1Document3 pagesAlgebra One Lesson 7.1Ryan AkerNo ratings yet

- Transition To College Math SyllabusDocument5 pagesTransition To College Math Syllabusapi-324575506No ratings yet

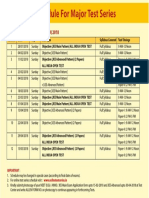

- Schedule For Major Test Series: Allen - Jee (Main + Advanced) 2018Document1 pageSchedule For Major Test Series: Allen - Jee (Main + Advanced) 2018HshsjNo ratings yet

- Individualized Education Program (With Secondary Transition)Document13 pagesIndividualized Education Program (With Secondary Transition)api-381289389No ratings yet

- Naplan Year9 Test3 2009 NON CALCULATOR PDFDocument8 pagesNaplan Year9 Test3 2009 NON CALCULATOR PDFpappadutNo ratings yet

- Case Study Developing Professional CapacityDocument7 pagesCase Study Developing Professional CapacityRaymond BartonNo ratings yet

- UCLA Math 33A SyllabusDocument2 pagesUCLA Math 33A Syllabuszmy8686No ratings yet

- COM 101 Syllabus Oral CommunicationDocument19 pagesCOM 101 Syllabus Oral CommunicationRo-elle Blanche Dalit CanoNo ratings yet

- MSC Oil & Gas Structural Engineering Course Descriptors 2015-2016Document18 pagesMSC Oil & Gas Structural Engineering Course Descriptors 2015-2016Xabi BarrenetxeaNo ratings yet

- How To Design A Didactic Sequence Study GuideDocument5 pagesHow To Design A Didactic Sequence Study GuideBryam AriasNo ratings yet

- Education Reform (REPORT)Document16 pagesEducation Reform (REPORT)Grace Vallejos Agos100% (1)

- Women in LeadershipDocument12 pagesWomen in Leadershipapi-296422388No ratings yet

- Literacy - FinalDocument11 pagesLiteracy - Finalapi-254777696No ratings yet

- P2P RubricDocument2 pagesP2P RubricRadu MarianNo ratings yet

- Improving English Tenses for Marathi StudentsDocument36 pagesImproving English Tenses for Marathi StudentsSohel BangiNo ratings yet

- Many RootsDocument62 pagesMany RootsJzf ZtrkNo ratings yet

- GCAS Student HandbookDocument18 pagesGCAS Student HandbookJason AdamsNo ratings yet

- Placement and Class GroupingsDocument3 pagesPlacement and Class Groupingsapi-205485325No ratings yet