Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Epilepsy Guidelines

Uploaded by

Sivaraj RamanOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Epilepsy Guidelines

Uploaded by

Sivaraj RamanCopyright:

Available Formats

EPILEPSY GUIDELINES 2011

OVERVIEW

In England and Wales there are between 260,000 and 416,000 people with active epilepsy. The incidence of epilepsy is around 50 per 100,000 per annum. The aim of the these guidelines is to provide guidance about the diagnosis, initial antiepileptic drug (AED) treatment, management of provoked seizures and the management of people with learning disability and epilepsy. This guideline also makes recommendations relating to contraception, pregnancy and the menopause; models of care for epilepsy and provision of information for patients and carers. Furthermore, this guidance had been developed to help achieve the outcomes set out in The NHS Outcomes Framework 2011/12 for example reducing the amount of unplanned time spent in hospital for patients with epilepsy.

MOTOR DIAGNOSIS,

CLASSIFICATION AND INVESTIGATION

MODELS OF CARE

A structured management system for epilepsy should be established in primary care. As with other chronic diseases, an annual review is desirable. The shared care management system adopted should seek to: Identify all patients with epilepsy, register/record basic demographic data, validate the classification of seizures and syndromes. make the provisional diagnosis in patients, provide appropriate information and refer to a specialist centre. monitor seizures, aiming to improve control by adjustments of medication or referral to hospital services. minimize side effects of medications and their interactions. Facilitate structured withdrawal from medication where appropriate, and if agreed by the patient. Introduce non-clinical interventions, and disseminate information to help improve quality of life for patients with epilepsy. address specific womens issues and needs of patients with learning disabilities.

Services should be provided in acute hospitals to enable probable recent onset seizures to be seen within two weeks of onset. Hospitals should provide services to review people with drug-resistant epilepsy. Subspeciality epilepsy clinics should be available to meet the needs of specific groups of patients (epilepsy in learning disability, in pregnancy, in adolescence and in potential surgical candidates. Each epilepsy teams should include epilepsy nurse specialists.

EPILEPSY GUIDELINES 2011

TREATMENT ALGORITHM

Starting antiepileptic drug (AED) treatment The decision to start AEDs should be made by the patient and an epilepsy specialist. AEDs should be offered after a first tonic-clonic seizure if: the patient has had previous myoclonic, absence or partial seizures. . the EEG shows unequivocal epileptic discharges. the patient has a congenital neurological deficit. the patient considers the risk of recurrence unacceptable.

TREATMENT CONTINUED

Provoked seizures Metabolic disturbances/ drugs Alcohol withdrawal Acute brain insult/ neurosurgery Correct/withdraw the provocative factor. Give benzodiazepines in the short term. Prophylactic AED treatment is not indicated Withdraw AEDs used to treat provoked seizures (unless unprovoked seizures occur later). AED treatment is not indicated AED side effects Commence AEDs in doses no higher than recommended by manufacturers. Warn patient of risks of potential side effects. Give instructions to seek urgent medical attention for rash, bruising or somnolence with vomiting. Give advice to minimize risk of osteoporosis (see below) No need to routinely monitor liver function tests and full blood count although these tests should be done prior to starting treatment. Psychological treatment of epilepsy Psychological treatments are not an alternative to pharmacological treatments, but their use can be considered in patients with poorly controlled seizures.

Concussive convulsions AED blood levels Are NOT routinely indicated (SIGN 2006)

Choice of AED monotherapy Partial and secondary generalized seizures Carbamazepine Lamotrigine Levetiracetam Oxcarbazepine Sodium valproate Primary generalized seizures Uncertain seizure types

Can be useful for o Adjustment of phenytoin dose o Assessment of adherence and toxicity

Sodium valproate Lamotrigine

Sodium valproate Lamotrigine

Drug treatment should only be started by a neurologist or epilepsy specialist

The side effect and interaction profiles should direct the choice of drug for the individual patient

Epilepsy resistant to monotherapy Review diagnosis of epilepsy and adherence to medication Consider combination therapy when: o Treatment with two first line AEDs has failed o The first well-tolerated drug substantially improves seizure control, but fails to produce seizure freedom at maximal dosage. o The choice of drugs in combination should be matched to the patients seizure type(s) and should be limited to two or at most three AEDs. Gabapentin, lacosamide, lamotrigine, levetiracetam, pregabalin, topiramate, zonisamide (alphabetical order) may be considered as adjunctive therapy dependent on patient and seizure type.

AED withdrawl Discuss after at least two years seizure freedom. Factors to be discussed include: chances of seizure recurrence, driving, employment risks and fear of further seizures and concerns about prolonged AED treatment. Withdraw drugs slowly, usually over a few months after consultation with ESN or specialist.

Vitamin D and bone density Phenytoin, phenobarbitone, carbamazepine and sodium valproate have been associated with reduced bone mineral density and increased fracture rates which are characteristic of osteoporosis. Vitamin D supplementation should be considered in patients who receive long term treatment with these drugs.

GENERIC PRESCRIBING IN PATIENTS WITH EPILEPSY SHOULD BE AVOIDED Changing the formulation or brand of AED is NOT recommended because different preparations may vary in bioavailability or have different pharmacokinetic profiles and, thus, increased potential for reduced effect or excessive side effects.

Surgical referral Consider if epilepsy is drug resistant, failing to respond to at least two AEDs separately or in combination

EPILEPSY GUIDELINES 2011

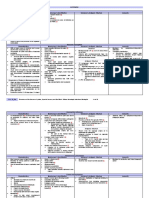

Table 1 Main adverse reactions of AEDs, which may be serious and rarely life threatening

AED Carbamzepine Clobazam Clonazepam Gabapentin Lacosamide Lamotrigine Levetiracetam Oxcarbazepine Phenobarbital Phenytoin Pregabalin Topiramate Valproate Vigabatrin Zonisamide Main adverse reactions Idiosyncratic (rash), sedation, headache, ataxia, nystagmus, diplopia, tremor, impotence, hyponatraemia, cardiac arrhythmia Severe sedation, fatigue, drowsiness, behavioural and cognitive impairment, restlessness, aggressiveness, hypersalivation and coordination disturbances. Tolerance and withdrawal syndrome As for clobazam Weight gain, peripheral oedema, behavioural changes, impotence, viral infection Dizziness, diplopia, headache, nausea Idiosyncratic (rash), tics, insomnia, dizziness, diplopia, headache, ataxia, asthenia Irritability, behavioural and psychotic changes, asthenia, dizziness, somnolence, headache Idiosyncratic (rash), headache, dizziness, weakness, nausea, somnolence, ataxia and diplopia, hyponatraemia Idiosyncratic (rash),severe drowsiness, sedation, impairment of cognition and concentration, hyperkinesias and agitation in children, shoulder-hand syndrome Idiosyncratic (rash), ataxia, drowsiness, lethargy, sedation, encephalopathy, gingival hyperplasia, hirsutism, dysmorphism, rickets, osteomalacia Weight gain, myoclonus, dizziness, somnolence, ataxia, confusion Somnolence, anorexia, fatigue, nervousness, difficulty with concentration/attention, memory impairment, psychomotor slowing, metabolic acidosis, weight loss, language dysfunction, renal calculi, acute angle-closure glaucoma and other ocular Nausea, vomiting, dyspepsia, weight gain, tremor, hair loss, hormonal in women Irreversible visual field defects, fatigue, weight gain Idiosyncratic, drowsiness, anorexia, irritability, photosensitivity, weight loss, renal calculi Life threatening AHS**, hepatic failure, haematological No No Acute pancreatitis, hepatitis, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, acute renal failure No AHS**, hepatic failure, haematological Hepatic failure, hepatitis*** AHS**, haematological AHS**, hepatic failure, haematological AHS**, hepatic failure, haematological Renal failure, congestive heart failure Hepatic failure, anhidrosis Hepatic and pancreatic failure No AHS**, anhidrosis

**Anticonvulsant hypersensitivity syndrome (AHS), anhdrosis and hepatic/pancreatic failure occur more often in children than in adults. AHS is a potentially fatal but rare reaction than can manifest as a rash, fever, tender lymphadenopathy, hepatitis or eosinophilia. There is usually cross-sensitivity between AEDs, which have the potential to cause AHS; these AEDs should be avoided in patients who have developed idiosyncratic reactions to one or another drug. The appearance of a rash is an early indicator that mandates the immediate discontinuation of the responsible agaent because it may progress to Stevens-Johnson syndrome and AHS.

EPILEPSY GUIDELINES 2011

LEARNING DISABILITY AND EPILEPSY

In the management of people with learning disability and epilepsy: Allow adequate time for the consultation Ensure the patient is accompanied by the carer familiar with the seizure types, frequency, possible side effects of medication, general health and behavior Provide information in an accessible form Liaise with other health professional involved If midazolam is needed for serial or prolonged seizures: o Give recognized training to carers with retraining every two years o Draw up and regularly review care plan, agreed between GP and specialist service All individuals with epilepsy and learning disability should have a risk assessment including o Bathing and showering o Preparing food o Using electrical equipment o Managing prolonged or serial seizures o The impact of epilepsy in social settings o SUDEP o The suitability of independent living, where the rights of the individual are balanced with the role of the carer.

EPILEPSY IN WOMEN

Women with epilepsy, who are of childbearing age, need additional advice about such issues as contraception, pregnancy and breastfeeding Advice on contraception should be given before young women are sexually active. When the combined oral contraceptive is given with an enzyme-inducing AED, a minimum of 50micrograms should be used. Also women should be warned that the pill`s efficacy may be reduced, If breakthrough bleeding occurs the dose should be increased. Taking the combined oral contraceptive pill and lamotrigine can result in a significant reduction in lamotrigine levels and lead to loss of seizure control. When a woman starts or stops taking oral contraceptives, the dose of lamotrigine may need to be adjusted. Information about the risk of epilepsy and AEDs in pregnancy and the need for folate and vitamin K should be given to all women of childbearing age and repeated at review appointments. Pregnancies in women with epilepsy should be supervised in an obstetric clinic with access to a physician in epilepsy.

DRIVING REGULATIONS EPILEPSY IN THE ELDERLY

In the management of elderly people with epilepsy: Nearly all de-novo seizures are focal in onset with or without secondary generalization. Underlying factors can often be identified e.g. tumor, dementia, cerebrovascular disease Complex partial seizures presenting as confusion may be misdiagnosed as psychiatric symptoms Post-ictal confusion can be prolonged in elderly patients Elderly patients are particularly sensitive to AED adverse event so low doses are recommended Drugs with a high propensity for neurotoxicity should be avoided In patients with multiple concomitant medications AEDs that do not have drug-drug interactions are preferred THE CURRENT EPILEPSY REGULATIONS FOR GROUP 1 AND GROUP 2 ENTITLEMENT GROUP 1 A person who has suffered an epileptic attack whilst awake must refrain from driving for at least one year from the date of the attack before a driving licence may be issued. A person who has suffered an attack whilst asleep must also refrain from driving for at least one year from the date of the attack. However, if they have had an attack whilst asleep more than three years previously and have had no attacks whilst awake since that original attack whilst asleep, then they may be licensed even though attacks whilst asleep may continue to occur. If an attack whilst awake subsequently occurs, then the formal epilepsy regulations apply and require at least one year off driving from the date of the attack. AND in both cases 3) i) so far as practicable, the person complies with advised treatment and check-ups for epilepsy, and ii) the driving of a vehicle by such a person should not be likely to cause danger to the public. GUIDANCE FOR CLINICIANS ADVISING PATIENTS TO SURRENDER THEIR DRIVING LICENCE IN THE CASE OF BREAK-THROUGH SEIZURES IN THOSE WITH ESTABLISHED EPILEPSY: In the event of a seizure, the patient must be advised not to drive unless they are able to meet the conditions of the asleep concessions. The patient should also be advised to notify the DVLA. In exceptional cases (e.g. seizure secondary to prescribing error), the clinician is advised to discuss the circumstances individually with the Medical Adviser at the DVLA before advising the patient on the appropriate licensing procedure.

REFERENCES

(Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) 2003. Epilepsy Quick Reference Guide. National Institute for Clinical Excellence. The Epilepsies: The diagnosis and management of the epilepsies in adults and children in primary and secondary care. Panayiotopolous, Principles of Anti-Epileptic Drug Therapy 2008 Brodie, Schachter & Kwan (2005) Epilepsy DVLA At a glance guide to current medical standards of fitness to drive 2011 Guidelines written by: Review Date: Dr Ruqqia Mir, consultant neurologist June 2013

EPILEPSY GUIDELINES 2011

INFORMATION FOR PATIENTS AND CARERS

Information should be given in an appropriate manner with sufficient time to answer questions. The type of information given should be recorded in the patient notes The following checklist should be used to help healthcare professionals to give patients and carers the information they need in an appropriate format: General epilepsy information Explanation of what epilepsy is* Probable cause Explanation of investigational procedures Classification of seizures* Syndrome Epidemiology Prognosis* Genetics Sudden Unexpected Death in Epilepsy(SUDEP) Antiepileptic drugs Choice of drugs* Efficacy* Side effects* Adherence* Drug interactions* Free prescriptions* Possible psychological consequences Perceived stigma* Memory loss* Depression Anxiety Maintaining mental well being Self esteem* Sexual difficulties Issues for women contraception* pre-conception* pregnancy and breastfeeding* menopause

Seizure triggers lack of sleep* alcohol and recreational drugs stress* photosensitivity Lifestyle driving regulations employment education (e.g. ES guidelines for teachers) Support organizations Addresses and telephone numbers of national and local epilepsy organizations. First Aid General guidelines* Status epilepticus *essential information

USEFUL CONTACTS AND WEBSITES

Epilepsy Action National Society for epilepsy Helpline 0808 800 5050 www.epilepsy.org.uk Helpline 01494 601 400 www.epilepsysociety.org.uk Epilepsy specialist nurse DVLA 01422 222568 www.dft.gov.uk/dvla

APPENDIX A

EPILEPSY GUIDELINES 2011

APPENDIX B

Investigations Electroencephalograpghy (EEG) EEG should not be used to exclude epilepsy. EEG can be used to support the diagnosis in patients in whom the clinical history indicates a significant probability of an epileptic seizure or epilepsy. EEG should be used to support the classification of epileptic seizures and epilepsy syndromes when there is clinical doubt EEG should be performed in young people with generalized seizures to aid classification and to detect a photoparoxysmal response Brain imaging Indicated unless there is a confident diagnosis of an idiopathic generalized epilepsy with response to AED treatment Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the modality of choice to identify underlying structural pathology. Computed tomography (CT) has a role in the urgent assessment of seizures, or when MRI is contraindicated Video EEG and other specialist investigations should be available for patients who present diagnostic difficulties

Important points in history taking in a patient suspected of having had one or more seizures

Features of the suspected seizure event Before the event Precipitating or provoking factors Preceding symptoms Duration of symptoms During the event Motor symptoms Sensory symptoms Level of awareness/ responsiveness Tongue biting or other injury Urinary incontinence Duration of the event After the event Level of alertness Confusion Duration of symptoms Pattern of events Duration Frequency Stereotyped or variable Patients History Previous medical history Birth history Childhood febrile convulsion(s) Severe head trauma of other neurological insult Psychiatric illness Family history Drug history Prescribed medication Over-the-counter medication Illicit drugs Alcohol use

A witness account can be very useful in aiding diagnosis (see appendix D). Also, with the increased availability of video recording with mobile phones. A recording of the actual event(s) can be a great help in an reaching an accurate diagnosis

APPENDIX C

Factors lowering seizure threshold Common Sleep deprivation Alcohol withdrawal Television flicker Epileptogenic drugs Systemic infection Head trauma Recreational drugs Antiepileptic non-compliance Menstruation Occasional Dehydration Barbiturate withdrawal Benzodiazepine withdrawal Hyperventilation Flashing lights Diet and missed meals Specific `reflex triggers Stress Intense exercise

APPENDIX D

EPILEPSY GUIDELINES 2011

CHECKLIST FOR COMPLETION OF AN EYEWITNESS REPORT

Keep a record of the dates and times that `seizures occur. Where was the person and what were they doing before the seizures? Did you notice any mood changes, such as excitement, anxiety or anger? Did the person mention any unusual sensations, such as odd taste or smell? Did the seizure occur without warning? What drew your attention to the person having a seizure (e.g. a cry, a fall, or body movements such as eyes rolling or head turning)? Did the person lose consciousness or appear confused? Did the person change colour (e.g. become pale, flushed or `blue)? If so, where (e.g. face, lips or hands)? Did the persons breathing alter (e.g. become noisy or difficult)? Did any part of their body stiffen, jerk or twitch? If so, which? Was there incontinence? Did they bite their cheek or tongue? Did the person do anything unusual such as mumble, wander about, fumble with their clothes or any objects? How long did the `seizure last? How was the person after the `seizure? Did the person feel tired, need to sleep? If so, for how long? How long was it before the person was able to resume normal activities? Did you notice anything else?

EPILEPSY GUIDELINES 2011

STATUS EPILEPTICUS

Prevention Carers should treat serial or prolonged seizures in the community with rectal diazepam according to an agreed protocol (protocol must include advice on when to transfer to hospital).

Patients with generalized tonic-clonic status epilepticus

Secure airway Give oxygen Assess cardiac and respiratory function Secure intravenous(IV) access in large veins Collect blood for bedside blood glucose monitoring and full blood count, urea and electrolytes, liver function tests, calcium, glucose, clotting, AED levels and storage for later analyses.

IMMEDIATE MEASURES

Give lorazepam 4mg IV (or diazepam 10mg IV if lorazepam is unavailable)

No response?

Delay in IV access in community?

Repeat after maximum of 10 minutes in hospital

Give 10-20mg diazepam rectally

Determine aetiology Any suggestion of hypoglycaemia: give 50ml 50% glucose IV Any suggestion of alcohol abuse or impaired nutritional status:give thiamine IV (as 2 pairs ampoules Pabrinex) Give usual AED treatment orally or by nasogastric tube (or IV if necessary for phenytoin, sodium valproate and Phenobarbital)

If status persists

WITHIN 30 MINUTES

Give fosphenytoin 18mg/Kg phenytoin equivalent IV, up to 150mg/min; or phenytoin 18mg/Kg IV, 50mg/min, both with ECG monitoring; or Phenobarbital 15mg/Kg IV, 100mg/min Call ITU to inform of patient

If status persists

>30 MINUTES

administer general anaesthaesia and admit to ITU monitor using EEG to assess seizure activity refer for specialist advice

You might also like

- Neuroscience Clerkship Teaching Vignettes on Cerebrovascular Disease and Changes in Mental StateDocument16 pagesNeuroscience Clerkship Teaching Vignettes on Cerebrovascular Disease and Changes in Mental Statehippocamper100% (1)

- Pediatric Myelination and LeukodystrophiesDocument41 pagesPediatric Myelination and LeukodystrophiesAna Bărdaș-ZugravuNo ratings yet

- Updates in The Treatment of Eating Disorders in 2022 A Year in Review in Eating Disorders The Journal of Treatment PreventionDocument12 pagesUpdates in The Treatment of Eating Disorders in 2022 A Year in Review in Eating Disorders The Journal of Treatment PreventionMarietta_MonariNo ratings yet

- Hypokalemia NCPDocument4 pagesHypokalemia NCPpauchanmnlNo ratings yet

- Anatomic LocalizationDocument9 pagesAnatomic Localizationkid100% (1)

- Neuropharmacology of Antiepileptic Drugs: P-Slide 1Document64 pagesNeuropharmacology of Antiepileptic Drugs: P-Slide 1Hasnain AbbasNo ratings yet

- Myoclonic Epilepsy With Ragged Red Fibers (MERRF)Document32 pagesMyoclonic Epilepsy With Ragged Red Fibers (MERRF)Alok Aaron Jethanandani0% (1)

- Childhood Epilepsy Etiology, Epidemiology & ManagementDocument6 pagesChildhood Epilepsy Etiology, Epidemiology & ManagementJosh RoshalNo ratings yet

- Neurology Lectures 1 4 DR - RosalesDocument20 pagesNeurology Lectures 1 4 DR - RosalesMiguel Cuevas DolotNo ratings yet

- Spinal Tracts: DR - Krishna Madhukar Dept. of Orthopaedics Bharati HospitalDocument65 pagesSpinal Tracts: DR - Krishna Madhukar Dept. of Orthopaedics Bharati HospitalKrishna Madhukar100% (1)

- Neurology ARCP Decision Aid 2014Document1 pageNeurology ARCP Decision Aid 2014LingNo ratings yet

- Localization of Brain Stem LesionsDocument35 pagesLocalization of Brain Stem LesionsHrishikesh Jha0% (1)

- Adult Clinical Case Scenarios Powerpoint Powerpoint 438386222Document68 pagesAdult Clinical Case Scenarios Powerpoint Powerpoint 438386222SAHAR100% (1)

- 2010 RITE DiscussionDocument111 pages2010 RITE DiscussionDhiren PatelNo ratings yet

- Neurology PearlsDocument18 pagesNeurology PearlsRjD100% (1)

- Neurology Shelf Exam Review - Part 2.newDocument14 pagesNeurology Shelf Exam Review - Part 2.newyogurtNo ratings yet

- 01-Guidelines For Use of Hypertonic SalineDocument13 pages01-Guidelines For Use of Hypertonic SalineSatish VeerlaNo ratings yet

- Draw It To Know It NotesDocument13 pagesDraw It To Know It Noteskat9210No ratings yet

- Epilepsy Lecture NoteDocument15 pagesEpilepsy Lecture Notetamuno7100% (2)

- Autism Spectrum Disorders: Isabelle Rapin Seminar On Developmental DisordersDocument45 pagesAutism Spectrum Disorders: Isabelle Rapin Seminar On Developmental DisordersmeharunnisaNo ratings yet

- Embryologic DefectsDocument62 pagesEmbryologic DefectsBenjamin AgbonzeNo ratings yet

- Pediatric Neurology History and Exam GuideDocument19 pagesPediatric Neurology History and Exam Guiderjh1895No ratings yet

- 13 Clinical EpilepsyDocument139 pages13 Clinical Epilepsyعبدالسلام الصايدي100% (1)

- Optic Neuritis - Continuum Noviembre 2019Document29 pagesOptic Neuritis - Continuum Noviembre 2019María Isabel Medina de BedoutNo ratings yet

- Cranial Nerve Exam Part 1Document9 pagesCranial Nerve Exam Part 1Jennifer Pisco LiracNo ratings yet

- Autonomic and Systemic Pharmacology DR DahalDocument119 pagesAutonomic and Systemic Pharmacology DR Dahalअविनाश भाल्टरNo ratings yet

- Neurologic EmergenciesDocument194 pagesNeurologic Emergenciesapi-205902640No ratings yet

- Clinical Neurology Answers OnlyDocument68 pagesClinical Neurology Answers Onlyanas kNo ratings yet

- (MicroB) 3.6 Brainstem LesionsDocument6 pages(MicroB) 3.6 Brainstem Lesionsnelson lopezNo ratings yet

- Neurological Physical Exam GuideDocument3 pagesNeurological Physical Exam Guidejyhn24No ratings yet

- MS Brain and Neurological DisordersDocument5 pagesMS Brain and Neurological DisordershaxxxessNo ratings yet

- Guideline Eeg Pediatric 2012Document60 pagesGuideline Eeg Pediatric 2012Chindia Bunga100% (1)

- Basics of EpilepsyDocument15 pagesBasics of EpilepsyDiana CNo ratings yet

- Birth DefectsDocument36 pagesBirth DefectsSohera NadeemNo ratings yet

- Promoting Neurosciences with Motor Stereotypies and Kluver-Bucy SyndromeDocument3 pagesPromoting Neurosciences with Motor Stereotypies and Kluver-Bucy SyndromewardahkhattakNo ratings yet

- Manual of Pediatric NeurologyDocument148 pagesManual of Pediatric NeurologyannisanangNo ratings yet

- Neurology Made Easy FinalDocument18 pagesNeurology Made Easy FinalDevin Swanepoel100% (1)

- Neurology Board ReviewDocument16 pagesNeurology Board ReviewNabeel Kouka, MD, DO, MBA, MPH67% (3)

- Rite 2011Document114 pagesRite 2011alugo22No ratings yet

- Anti Platlet and StrokeDocument25 pagesAnti Platlet and StrokeSurat TanprawateNo ratings yet

- Chorea Approach PDFDocument1 pageChorea Approach PDFdrsushmakNo ratings yet

- Basic Mechanisms Underlying Seizures and EpilepsyDocument44 pagesBasic Mechanisms Underlying Seizures and EpilepsytaniaNo ratings yet

- Localisation in NeurologyDocument19 pagesLocalisation in NeurologyArnav GuptaNo ratings yet

- Pharmacology Student Activity Sheet on Antipsychotic and Anxiolytic DrugsDocument5 pagesPharmacology Student Activity Sheet on Antipsychotic and Anxiolytic DrugsChelsy Sky SacanNo ratings yet

- Cerebrovascular Disorders: Causes, Types, Symptoms & Treatment of StrokesDocument4 pagesCerebrovascular Disorders: Causes, Types, Symptoms & Treatment of StrokesMhae De GuzmanNo ratings yet

- Descending Tracts: Dr. Niranjan Murthy H L Asst Prof of Physiology SSMC, TumkurDocument23 pagesDescending Tracts: Dr. Niranjan Murthy H L Asst Prof of Physiology SSMC, Tumkurnirilib100% (1)

- Pediatric Epilepsies: This Is Only For UAMS Neurology Internal UseDocument57 pagesPediatric Epilepsies: This Is Only For UAMS Neurology Internal UsePlay100% (1)

- Neuro Summaries PDFDocument65 pagesNeuro Summaries PDFBEATRICE SOPHIA PARMANo ratings yet

- Anticonvulsants 2Document1 pageAnticonvulsants 2Taif Salim100% (1)

- Ring Enhancing LesionsDocument50 pagesRing Enhancing LesionsVivek GuptaNo ratings yet

- Acute Ischemic Stroke ManagementDocument38 pagesAcute Ischemic Stroke ManagementAndrio GultomNo ratings yet

- A Clinician's Approach To Peripheral NeuropathyDocument12 pagesA Clinician's Approach To Peripheral Neuropathytsyrahmani100% (1)

- Neuromuscular Disorders 2016Document68 pagesNeuromuscular Disorders 2016Alberto MayorgaNo ratings yet

- cEEG Monitoring in The ICU: Treating Subclinical Seizures Is Cost EffectiveDocument26 pagescEEG Monitoring in The ICU: Treating Subclinical Seizures Is Cost EffectiveVijay GadagiNo ratings yet

- Handbook Neurology PDFDocument68 pagesHandbook Neurology PDFLeonardus EricNo ratings yet

- Differential Diagnosis of Cherry-Red Spot at MaculaDocument4 pagesDifferential Diagnosis of Cherry-Red Spot at MaculaVarun BoddulaNo ratings yet

- Seizure and EpilepsyDocument18 pagesSeizure and EpilepsyJamal JosephNo ratings yet

- Aicardi’s Diseases of the Nervous System in Childhood, 4th EditionFrom EverandAicardi’s Diseases of the Nervous System in Childhood, 4th EditionAlexis ArzimanoglouNo ratings yet

- Quick Guide - Antenatal Care NHSDocument28 pagesQuick Guide - Antenatal Care NHSLimfc UfscNo ratings yet

- Psoriasis TopicalDocument17 pagesPsoriasis TopicalSivaraj RamanNo ratings yet

- Warfarin-Herbs, Supplements, Foods InteractionDocument14 pagesWarfarin-Herbs, Supplements, Foods InteractionSivaraj RamanNo ratings yet

- Psoriasis TopicalDocument17 pagesPsoriasis TopicalSivaraj RamanNo ratings yet

- Epilepsy HandbookDocument32 pagesEpilepsy HandbookSivaraj RamanNo ratings yet

- NICE Epilepsy GuidelinesDocument20 pagesNICE Epilepsy GuidelinessachinbatsNo ratings yet

- 2018 Jordanian Conference BookletDocument51 pages2018 Jordanian Conference BookletAurelian Corneliu MoraruNo ratings yet

- A Seminar Report On "Attitude": Seth Jai Parkash Mukand Lal Institute of Engineering and Technology, Radaur (Yamunanagar)Document20 pagesA Seminar Report On "Attitude": Seth Jai Parkash Mukand Lal Institute of Engineering and Technology, Radaur (Yamunanagar)BamanNo ratings yet

- Ana de Castro ResumeDocument1 pageAna de Castro Resumeapi-251818080No ratings yet

- Healing Landscapes: Gardens As Places For Spiritual, Psychological and Physical HealingDocument49 pagesHealing Landscapes: Gardens As Places For Spiritual, Psychological and Physical HealingrajshreeNo ratings yet

- Beyond The Manual: The Insider's Guide To Prolonged Exposure Therapy For PTSDDocument9 pagesBeyond The Manual: The Insider's Guide To Prolonged Exposure Therapy For PTSDmakolla007No ratings yet

- Jcad 13 2 33Document11 pagesJcad 13 2 33ntnquynhproNo ratings yet

- Healthy Narcissism and NPD, SperryDocument8 pagesHealthy Narcissism and NPD, SperryjuaromerNo ratings yet

- Horticulture Therapy For Physically and Mentally Challenged ChildrenDocument41 pagesHorticulture Therapy For Physically and Mentally Challenged ChildrenbelamanojNo ratings yet

- Revised Case Report - HemorrhoidsDocument47 pagesRevised Case Report - Hemorrhoidschristina_love08100% (2)

- UT Trauma HandbookDocument49 pagesUT Trauma Handbooksgod34No ratings yet

- Complete Guide To Communication Problems After StrokeDocument22 pagesComplete Guide To Communication Problems After Strokeapi-215453798100% (1)

- Program CraiovaDocument9 pagesProgram Craiovaonix2000No ratings yet

- Foreign Qualification Recognition GuideDocument2 pagesForeign Qualification Recognition Guidesatishg99No ratings yet

- Books About GroupsDocument25 pagesBooks About GroupsgerawenceNo ratings yet

- Argumentative Essay About LDRDocument2 pagesArgumentative Essay About LDRRenebert Jr MabayoNo ratings yet

- Drug Study - Potassium ChlorideDocument6 pagesDrug Study - Potassium ChlorideBalloonsRus PHNo ratings yet

- #2&3 - 18 Street, West Bajac-Bajac, Olongapo City Telefax: (047) 6023200 Mobile: (+63) 920 9020591Document10 pages#2&3 - 18 Street, West Bajac-Bajac, Olongapo City Telefax: (047) 6023200 Mobile: (+63) 920 9020591Leo Arcillas Pacunio100% (1)

- Yashica PDFDocument7 pagesYashica PDFmindpriestsNo ratings yet

- 2017 RockFloss Instructions v15b PDFDocument2 pages2017 RockFloss Instructions v15b PDFBernardus EdwinNo ratings yet

- Self-Esteem Disturbance: Submitted To: Ma'am Sadia Kanwal Submitted By: Fatima AzharDocument15 pagesSelf-Esteem Disturbance: Submitted To: Ma'am Sadia Kanwal Submitted By: Fatima AzharbinteazharNo ratings yet

- Caries Predication, Risk Assessment and Treatment PlanningDocument74 pagesCaries Predication, Risk Assessment and Treatment PlanningmohammadNo ratings yet

- Gad-7 Questionnaire SpanishDocument86 pagesGad-7 Questionnaire Spanishrowanpurdy100% (1)

- Pharmacology of Endocrine System-NursingDocument58 pagesPharmacology of Endocrine System-NursingRaveenmayiNo ratings yet

- Sigmund Freud's TheoryDocument22 pagesSigmund Freud's TheoryGil Mark B TOmas100% (2)

- Better Living With COPDDocument108 pagesBetter Living With COPDPrem AnandNo ratings yet

- 4 5800639631472986150Document416 pages4 5800639631472986150MDDberlyYngua100% (1)

- Psychoanalytic EssayDocument7 pagesPsychoanalytic Essayapi-462360394No ratings yet

- Osma y Barlow 2021 PU en SpainDocument15 pagesOsma y Barlow 2021 PU en Spaingerard sansNo ratings yet