Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Evolution of Air India Versus Indian Railways

Uploaded by

hajo44Original Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Evolution of Air India Versus Indian Railways

Uploaded by

hajo44Copyright:

Available Formats

Recent development of Air India versus Indian Railways: A comparison of performance characteristics and good governance

Hans Huber, Shailesh J. Mehta School of Management, Indian Institute of Technology - Bombay, Powai, 400076, Mumbai hhuber@iitb.ac.in

Abstract: Rather than conducting institutional analysis (by means of transaction cost economics) to improve governance with regards to Public Service Units (PSUs), a more critical approach is suggested. The intent is to avoid tunnel-vision from applying theories of one discipline only and to highlight universal interdependencies that may matter for diverse sets of PSUs. Rather than forcing one theory on to reality, the author pursues inductive reasoning by testing acquired industry expertise against established templates for liberalization of PSUs. Inductive reasoning is considered a prerequisite for developing valid system-perspectives that would fundamentally improve our understanding of PSUs and their effective governance.

Recent development of Air India versus Indian Railways: A comparison of performance characteristics and good governance

Comparing the performance of Indian Railways with that of Air India should be an intuitive exercise that allows stressing fundamental issues pertaining to the outlook of two of Indias most prominent PSUs (see Table 1 for a comparison of scale of operations). Although a previous paper (Goyal A., 2008) had already applied principles of Transaction Cost Theory (TCE) to a similar topic, its conclusions can appear ambiguous, providing little scope for effective implementation. Other research compared productivity between Air India and other private airlines in India (Bansal S.C. et al., 2008). Although this approach may be proven, again it failed to make any clear recommendations as to how the strategy of Air India needed to be changed. What is probably more irritating is the fact that both approaches failed to raise a red flag and correctly predict the path to doom that Air India had chosen. In particular, no issues were found regarding the merger activities of NACIL during 2008, on which the author had voiced serious concerns1 before (Huber H. and Lawrence C., p.67). This concern stood in stark contrast with the support from prominent trade associations and lobbyist (see CAPA, 2009, p.3).

Bringing the discussion to a factual level that allows the independent observer to take a stand seems imperative. As it is the public interest that is at stake, not only from the taxpayers perspective (by capital injection or financing of unneeded aircraft purchases): the real issue is about the development path of India as a nation, i.e. the sustained ability of the Government to provide freedom and space to its people through mobility at affordable prices. Such an approach needs to go beyond classic microeconomic analysis, although it would remain deeply economic and political in nature. At this point a strong interdependency between both PSUs becomes clear: losses of one PSU constrain the Governments (GoI) ability to invest in other modes of transport (deficit spending incurring higher interest rates put aside). Or vice versa, the surpluses made by one PSU (for example through intelligent and responsible management) will tend to subsidize the other loss-making PSU (where poor management or corruption may be at cause). Such inequity becomes all the more scandalous, if it is the common man relying on inexpensive and

1

A parliamentary enquiry (COPU) was undertaken some months after the interview. Findings supported many of the authors arguments. 2

accessible railway service that eventually has to foot the bill, whereas the subsidized operator is catering to the upper-middle and upper classes. To what extent such win-lose patterns are accurate, of course, depends on the scale of financial surpluses/losses that are involved.

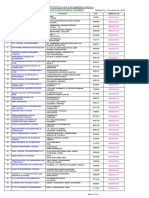

Table 1: Scale of operations

Indian Railways Pax (m) Pax-km (m) Net-ton-km (m) Personnel Wage/Op.Exp. Air India Pax (m) Rev-pax-km (m) Rev-ton-km (m) Personnel Wage/Op.Exp.

2003/04 5,112 541,208 384,074

2004/05 5,361 575,702 411,280

2005/06 5,725 615,614 441,762

2006/07 6,219 694,794 483,422

2007/08 6,524 769,956 523,196

2008/09 6,920 838,032 522,002

1,441,400 1,334,400 1,412,400 1,406,400 1,394,418 1,386,011 53.0% 52.8% 52.5% 49.7% 47.5% 55.6%

3.8 15,549 1,801 15,572 18.2%

4.4 19,184 2,239 15,914 15.7%

4.4 20,876 2,397 15,884 13.5%

4.4 19,615 2,240 15,376 13.6%

13.3 31,295 3,729 32,287 18.1%

10.5 26,436 3,235 31,106 17.7%

(source: Annual Reports)

With the author being a transport economist from abroad, political parties in India are not his prime concern. But the political system in India shows that local constituencies, be them in Bihar or Nagpur, may in the end matter for obtaining ever new funds without any justification on commercial grounds. Also, accountability seems inexistent (numerous examples show that near identical problems do exist in Western countries as well). In other words, no theory (i.e. transaction cost economics) can really explain the tale of two transport PSUs in India: one which had undergone a spectacular transformation, the other factually left bankrupt but no one willing to admit it.

Situation before 2004

By the late 1990s, the situation of Indian Railways (IR) was judged to be critical and unsustainable. In July 2001, the Rakesh Mohan committee saw IR as being stuck in a debt trap, partly due to important outlays that had been required for infrastructure maintenance and investment. IRs ability to self-generate funds had been considered as inadequate.

The idea of possible privatization had met with strong opposition from employees and unions, and thus was abandoned. Issues included Universal Service Obligation, improvements in both cost and quality, and measures to curb political rent extraction due to the impact that ticket pricing could have on state elections. The official recommendations that were given could be qualified as following the canonical neo-liberal template: for example, investments should be rationalized on a purely commercial basis, cross-subsidies between freight and passenger service be stopped, and prices be increased to cover costs. It was found that there was 25% excess manpower layoffs seemed the natural choice to improve productivity. Investment focus should be laid to the golden quadrilateral, i.e. railways linking Delhi, Mumbai, Chennai and Kolkata, along with other important cities that were en route. Privatization of IR should remain an option and the highly integrated concern was suggested to be split into independent entities that could be sold off selectively. The expert committee specifically opposed the smaller zones that eventually would be drawn. With hindsight, one can say that it had benefitted IR not to have implemented these recommendations. It is safe to say that transformation of IR seemed far from obvious when Lalu Prasad took over as Minister in 2004.

At the same time, Air India (AI) seemed in a much less critical position. Although the carrier had been hit by the 9/11 events and losses had worsened in fiscal 2002/03 (to reach minus Rs.190 crore from operations), by the following year the company had turned profitable again (Rs. 33 crore in operations). Although aviation was known to be cyclical and vulnerable to demand shocks, the overall growth prospects for the industry were favorable and competition with the private carriers seemed well coordinated (unlike intense competition that had unfolded on many routes in Europe or the US after liberalization).

On different growth paths

Air India despite occasional losses appeared as a financially manageable entity, simply because IR seemed an elephant whose health would affect the GoI budget much more than AIs did. Exhibit 1 shows how both PSUs have developed in terms of financial results during the tenure of the respective ministers, i.e. between 2004 and 2009 for Mr. Prasad and from 2004 to 2010 for Mr. Patel2.

Exhibit 1: Curves for Revenues and Gross Profit

IR: Revenue 90,000 80,000 70,000 60,000 50,000 40,000 30,000 20,000 10,000 0 -10,000 2003/04 2004/05

AI: Revenue

IR: Gross Profit

AI: PBT

2005/06

2006/07

2007/08

2008/09

(source: Annual Reports)

By FY 2008/09 revenue of IR had grown by 68.6%, that of AI by 74.3%. Considering a higher base effect, IRs performance was remarkable. Looking at two curves that move at about the same levels, growth in Gross Profit with IR has continuously exceeded that in Revenues with AI, except for fiscal 2008/09 (where IR had sacrificed profit growth for increases in revenues). As

2

Annual Reports for FY 2009/2010 were yet unavailable as of Feb.10th, 2011 5

shown before, AIs results from operations steadily deteriorated, with CAG reports claiming that losses for 2009/10 were actually amounting to Rs.8,589 crore3. Exhibit 2 shows the ratio of respective cash-flows between AI and IR4.

Exhibit 2: Ratios for Cash-Flows (Operations, Investment, Financing) between AI and IR

AI/IR: CF-Ops 120.0% 100.0% 80.0% 60.0% 40.0% 20.0% 0.0% -20.0% -40.0%

AI/IR: CF-Invest

AI/IR: CF-Finance

2004/05

2005/06

2006/07

2007/08

2008/09

(source: Annual Reports)

It can be seen that negative cash-flows from operations of AI had worsened to 18% as a percentage of IRs positive cash-flows by 2008/09. For 2009/10 this ratio was expected to worsen. Investment undertaken by AI had reached the equivalent of some 22% of IRs total capital expenditures for each of the last 2 years of the observed period. These investments had been largely due to the controversial order of 111 Boeing aircraft, including the appropriately named Dreamliner 787-type5. Most impressively, the ratio of cash-flows obtained through borrowing from the government reached 112% of that which had been provided to IR.

3 4

see Times of India, Has Air India understated loss?, February 9, 2011 The ratio for investments actually is understated as the exact position could not be found in IRs Annual Reports. As a reasonable proxy the position capital expenditures was substituted for IR. 5 Controversy had arisen as AI had a long history and experience in leasing aircraft. 6

Comparing key operations

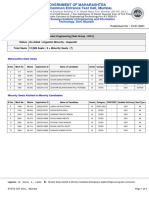

Table 2 compares important cost components as a ratio of operational output for both PSUs.

Table 2: Ratios for operational cost over output

Indian Railways Op.Exp./Pax-km (Rs.) Op.Exp./NTK (Rs.) Wage/Pax-km (Rs.) Wage/NTK (Rs.) Air India Op.Exp./Pax-km (Rs.) Op.Exp./RTK (Rs.) Wage/Pax-km (Rs.) Wage/RTK (Rs.)

2003/04 2004/05 2005/06 2006/07 2007/08 2008/09 6-yr.Chg. 0.7 1.0 0.4 0.5 0.7 1.0 0.4 0.5 0.7 1.0 0.4 0.5 0.7 1.0 0.4 0.5 0.7 1.0 0.3 0.5 0.9 1.4 0.5 0.8 17.5% 33.9% 23.2% 40.4%

3.9 33.9 0.7 6.2

3.9 33.7 0.6 5.3

4.4 38.5 0.6 5.2

5.0 44.1 0.7 6.0

5.7 47.9 1.0 8.6

7.1 58.4 1.3 10.3

81.8% 72.1% 76.5% 67.1%

(source: Annual Reports)

The results are striking: Operating Expenses per Revenue-Passenger-Kilometer at Air India have multiplied to about 8 times that of IR (when the new ministers had taken over, the ratio stood at 5.5 only). The ratio in terms of Net-tons-kilometers (or Revenue-ton-kilometers with AI) has lowered somewhat from some 44 to 42, without changing the fundamental disadvantage in costs for AI with regards to Cargo. Although wages have historically constituted over 50% of total operating costs with IR, wages per passenger-kilometer have grown by a moderate 23% as compared to 77% with AI over the 6-year period. This is a remarkable finding, as increased capital spending (new airports, new aircraft, merger consulting, route restructuring, etc.) should have allowed reducing this cost component as a fraction of AIs operational performance. When comparing wage costs in terms of net-ton-kilometers, IRs attention to operational performance managed to keep this figure at a competitive Rs.0.5 per NTK (with an exceptional spike in 2008/09, probably due to the industrial slow-down and implementation of the 6th pay7

commission). As with AI, the wage/RTK ratio had nearly doubled during 5 years of tenure (and was reckoned to worsen even more in the last year of the incumbents office). Obviously, these numbers could be analyzed more in detail (with break-downs for the different departments involved, etc.), but they are convincingly stating a chasm of competitive handicap for AI when it comes to cargo (as well as an increasing disadvantage with regards to passenger traffic).

If it had not been for international operations with higher load factors and longer distances flown, AIs deteriorating ratios would have been even more catastrophic. In other words, AI has stopped performing domestically, despite of mega-investments undertaken in favor of Boeing Corp., whereas IR has shown to the world that labor-intensive operations within India were economically viable and productivity could be increased.

Internalizing competition by Strategic Transformation

According to the author, a great deal of this success can be explained by IRs capability to internalize competition within its organization6. This internalization was made possible through a re-structuring of the existing 9 zones into 16 new ones, which were to be divided into 67 divisions in 2002 (see Exhibit 3). It is interesting to look at this measure - which had initially been opposed by many experts - to find positive externalities that it created both within IR, but also with regards to other stakeholders (GoI, passengers and freight, suppliers, etc.). Several effects stand out, with many of them resembling very closely the welfare effects that are being promised through market competition:

Semi-autonomous zones of operation One obvious feature of each zone is its focus on decentralized activities and a local provision of near complete value chains relating to railway operations (with separate departments for Accounts, Civil Eng., Commercial, Electrical Eng., Mechanical Eng., Medical, Personnel, Operations, Safety, Security, Signal & Telecom, Stores). A General Manager in each zone supervises the Principal Heads of each Department. As a consequence of the increase in number

6

None any of the case studies written on IRs actually discusses the fundamental role of zonal transformation. 8

of zones, the number of interchange points for given routes increased too. However, the often decried complexity and inoperability due to the reorganization has not materialized. Exhibit 3: Zonal reorganization of IR

(source: IR web-site) The following advantages can be observed: Comparability of cost structures and performance

This re-partition into smaller zones allowed for a better comparability of incurred costs and corresponding output, i.e. operational performance. Ceteris paribus, the more zones that were comparable, the lower the likeliness for manipulation and the easier it was to establish reliable benchmarks. In the case of inefficiencies, both the locus and root-causes of such became more traceable more easily.

9

Preventing collusion among General Managers

Increasing the number of zones from 9 to 16 made it significantly more difficult to form a nexus of relationships and mutual influences outside of organizational control. The allocation of zonal responsibilities to a wider base of General Managers also created a pool of new candidates for replacing underperformers.

Transparency and improved incentives

IR Annual Reports are extremely detailed with regards to operational performance along numerous benchmarks. It can be assumed that the same data exists for each zone and that it is disseminated openly among them. This provides for a constructive stimulus to improve operations, along with the possibility to actually influence the outcome locally (due to a high degree of zonal operational autonomy)7.

Geographic segmentation of operations The other criterion that is usually missing from economic analysis (be it institutional, microeconomic or organizational) but is significantly impacting on positive externalities is that of spatial separation. If there was geographic overlap between the zones, issues of transfer pricing, cross-subsidies and blurred transparency would arise. Effectiveness of the outlined measures could be seriously compromised. Thus, clear regulation and understanding of the interfaces between the various zones (i.e. clearly defined interchange points for each route) are required.

One of the fundamental hypotheses for market competition being free entry/exit and fluidity among firms, IR could hardly claim such conditions to prevail. However, as IR has proven that zones (or divisions) could undergo important restructuring, many of the welfare effects that are usually being attributed to market competition, were obtained. This, of course, raises fundamental questions about the legitimacy of liberalization and privatization of PSUs in India (as well as abroad).

This is another example of creating significant incentives within a hierarchy 10

Why Transaction Cost Economics has not helped to govern Air India

The example of IR has shown that public ownership was able to create significant incentive throughout an organization with 1.4 m employees, whereas any privatization efforts for AI have repeatedly been put on hold because of lack of interest from investors (even before massive losses had occurred). Apparently, high-powered incentives through privatization and market competition were not reckoned to suffice to get the company back on track.

The industry structure for IR (a monopoly) per se has never guaranteed profits for the PSU in the past. With regards to AI, very close coordination between all major carriers in India has been a top priority during the previous Ministers tenure. Market structure was (and still is) much closer to oligopoly than competition. This observation was confirmed by the quasi-simultaneous merger of 6 major airlines into 3 during spring 2008. Again, the inability to operate efficiently and profitably in such a favorable context is noteworthy, but escapes any clear prediction from TCE.

The nature of transactions that are prevalent in aviation could be interpreted in light of their asset specificity, frequency or uncertainty. Depending on these criteria, contracts that are incomplete would show higher or lower transaction costs, depending on the organizational form (markets versus hierarchies) through which they are being performed. In reality, it becomes near impossible to determine whether assets being used with AI were any more specific, transactions more frequent or uncertain as compared to those with IR. For example, one may say that the acquisition of a new and more sophisticated aircraft would impact on asset specificity and thus favor organizational integration through hierarchies. Such an assertion, however, fails to identify the key transactions that need to be analyzed and also ignores the fact that management does not need to buy such aircraft8, but could lease it. Appropriate technology choices, of course, need to be made; but it is the effective utilization of technology more than transaction costs which will assure the PSUs performance. In practice, one may say that both in terms of asset specificity as well as frequency of transactions, it is the airline-airport nexus that mostly would require organizational integration, i.e. hierarchy. However, such an intuitive arrangement can hardly be

8

Similarly, it remains the decision of IR to decide if, where and when asset-specific high-speed railway corridors would be launched. 11

found with todays globalized air traffic system. IR, in contrast, has laid more emphasis on such clearly hierarchical, yet localized transactions in its organizational format with 16 zones. Significantly, the spatial (geographic) component that seems quintessential for structuring and planning in transport has never been integrated into TCE. The real issue seems to be more about decentralized allocation of control over technology rather than expensive technology investments that would yield high-powered incentives which in turn could substitute for administrative control.

At this point, particularly when comparing AI with IR, it becomes clear that outsourcing of operations (another management spin-off from TCE) will not address the fundamental operational problems in the context of Indian Aviation.

In our analysis, the most relevant application of TCE probably pertains to Separation of Powers, although the original term dates back to Frenchman Montesquieu. TCE postulates that conflict of interest of an agent may actually make him over-spend on expenditures if he is to gain from them (through himself or related third parties). It suggests that spending would be lower if members who do not represent special interests are given special powers This hierarchical process strengthens collective interests (Goyal A., 2008, p.125). Although it is difficult to see how the position of the former Minister responsible for AI was structurally any different from that of IR, their actual handling of budget matters has been considerably asymmetric. It is true that independent control over budgetary processes and monitoring can make incentives lowpowered. However, the case of AI shows that repeated critical notes from CAG, COPA, etc. failed to have any noteworthy impact on highly contestable decisions taken by MoCA. In contrast, the exemplary transformation of IR including its relatively sovereign planning of investments, continue to serve as case studies worldwide.

A potential conflict of interest might also permeate inside the GoI as many Ministers heading PSUs are coalition partners with control over electoral bases in their home constituencies. This may make it near impossible for a coalition GoI to effectively discipline inadequate agents. However, as our comparison shows, TCE fails to explain the differences in budget allocation between both Ministries. In the end, it might be 18th-century Montesquieu with his principles on

12

the separation of political powers into a strong and independent Executive, Legislative and Judiciary that would prevail. The future development of India to a great extent will depend on the independence of these branches and the control powers granted to several of its national agencies (i.e. Comptroller & Auditor General, Competition Commission of India, Committee on Public Undertakings, etc.).

13

References:

Bansal, S.C., Khan, M.N., Dutt, V.R. (2008): Economic liberalization and Civil Aviation Industry, Economic & Political Weekly, August 23, pp.71-76

CAPA (2007): Aviation consolidation looming in India, Outlook, 2007

CAPA (2009): An aviation agenda for the next Indian government, Perspectives, May, pp.1-16

Goyal, Ashima (2008): Governance in Indias public transport systems: comparing Indian Railways and Airlines, Economic & Political Weekly, July 12, pp.119-127

Goyal, Ashima (2003): Budgetary processes: a political economy perspective, chapter 2.2. in S. Morris (ed.), India Infrastructure Report 2003, Public Expenditure Allocation and Accountability, 3i Network and Oxford University Press, New Delhi

Huber, Hans (2009): Strategic Flexible Planning and Real Options for Airport Development in India, Economic & Political Weekly, February 21, pp.43-50

Huber, Hans (2009): Planning for balanced growth in Chinese air traffic: a case for statistical mechanics, Journal of Air Transport Management, 16, pp.178-184

Huber, H., Lawrence, C. (2009): Corporate Strategy (Interview), The Analyst, ICFAI Press, 9, pp.66-67

Mohan, Rakesh et al. (2001): The Indian Railways Report on Policy Imperatives for Reinvention and Growth (Vol. I & II) by Expert Group on Indian Railways, Ministry of Railways, Government of India, New Delhi

Wikipedia (2011): http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Montesquieu, accessed on February 10

14

Williamson, Oliver (1999): Public and private bureaucracies: a transaction cost economics perspective, Journal of Law, Economics and Organization, 15, 1, pp.306-342

15

You might also like

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- NSP Scholarship Notice UKA 2023-2024Document6 pagesNSP Scholarship Notice UKA 2023-2024rahulsurroy.agtNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Institution of Engineers (India) : List of Institutional MembersDocument14 pagesThe Institution of Engineers (India) : List of Institutional MembersVikas GowdaNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Applied-Beekeeping Industry in India Future Potential-Tarunika Jain AgrawalDocument8 pagesApplied-Beekeeping Industry in India Future Potential-Tarunika Jain AgrawalImpact JournalsNo ratings yet

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Aditya Mukherjee - Empire, How Colonial India Made Modern BritainDocument11 pagesAditya Mukherjee - Empire, How Colonial India Made Modern BritainBidisha SenGuptaNo ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- CAPF 2020 WR ListwithName Eng FDocument29 pagesCAPF 2020 WR ListwithName Eng FChintu SikarwarNo ratings yet

- Safal Yuva - Yuva Bharat Drive in Andhra & TelanganaDocument7 pagesSafal Yuva - Yuva Bharat Drive in Andhra & TelanganaVivekananda KendraNo ratings yet

- Food Packaging - Acharya NG Ranga Agricultural UniversityDocument8 pagesFood Packaging - Acharya NG Ranga Agricultural UniversityKumkum CrNo ratings yet

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Helpdesk NumbersDocument3 pagesHelpdesk NumbersPrakash KumarNo ratings yet

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- CBSE Class 8 Social Science History Notes Chapter 1 How When and WhereDocument2 pagesCBSE Class 8 Social Science History Notes Chapter 1 How When and WhereDhanya RamkumarNo ratings yet

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- 2017Document152 pages2017Satyakam MishraNo ratings yet

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- School Contact/email: GurgaonDocument14 pagesSchool Contact/email: GurgaonsimoneNo ratings yet

- IAS History 2003 MainsDocument3 pagesIAS History 2003 MainsgrsrikNo ratings yet

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Limited Companies AhmedabadDocument96 pagesLimited Companies Ahmedabadpsavla62320% (1)

- 3209 - K J Somaiya Institute of Engineering and Information Technology, Sion, MumbaiDocument6 pages3209 - K J Somaiya Institute of Engineering and Information Technology, Sion, Mumbaisarcastic chhokreyNo ratings yet

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- TamilnaduDocument26 pagesTamilnaduimthi2ndmailNo ratings yet

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Ug List 201617Document6 pagesUg List 201617Megha PatilNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- 1st List of Admitted or Rejected Candidates For RTR - A Examination at Mumbai CenterDocument33 pages1st List of Admitted or Rejected Candidates For RTR - A Examination at Mumbai CenterTejaswi DattaNo ratings yet

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- SYNOPSIS IASbabas TLPDocument6 pagesSYNOPSIS IASbabas TLPchenshivaNo ratings yet

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- 2013 MBA Student Profile BookDocument44 pages2013 MBA Student Profile BookAninda MukherjeeNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Public ExpenditureDocument7 pagesPublic ExpenditureHarsh ShahNo ratings yet

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Hni 72Document1 pageHni 72Arsh AhmadNo ratings yet

- Calendar 12Document20 pagesCalendar 12Hotel EkasNo ratings yet

- FMCG & Durable GoodsDocument69 pagesFMCG & Durable GoodsSaurav GautamNo ratings yet

- Companies List - 04102023Document10 pagesCompanies List - 04102023sandhiyathangavelu03No ratings yet

- GST Master Upload Template Format V1 LatestDocument86 pagesGST Master Upload Template Format V1 LatestNaveenNo ratings yet

- Spring 2023 - PAK301 - 1Document2 pagesSpring 2023 - PAK301 - 1Muhammad ZeeshanNo ratings yet

- West Bengal CultureDocument12 pagesWest Bengal Cultureprabhat dalaiNo ratings yet

- The Foreign Trade Policy of India FinalDocument49 pagesThe Foreign Trade Policy of India FinalViraj WadkarNo ratings yet

- CBSE Class 10 History Notes Chapter 2Document1 pageCBSE Class 10 History Notes Chapter 2Sonali MalikNo ratings yet

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- PS - 14 - Rise of Muslim Nationalism in South Asia and Pakistan MovementDocument31 pagesPS - 14 - Rise of Muslim Nationalism in South Asia and Pakistan MovementBali Gondal100% (2)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)