Professional Documents

Culture Documents

USAM 9-131.000 The Hobbs Act - 18 U.S.C. 1951

Uploaded by

reydel_santosOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

USAM 9-131.000 The Hobbs Act - 18 U.S.C. 1951

Uploaded by

reydel_santosCopyright:

Available Formats

USAM 9-131.000 The Hobbs Act - 18 U.S.C.

1951

http://www.justice.gov/usao/eousa/foia_reading_room/usam/t...

US Attorneys > USAM > Title 9 > USAM Chapter 9-131.000 prev | next | Criminal Resource Manual

9-131.000 THE HOBBS ACT18 U.S.C. 1951

9-131.010 9-131.020 9-131.030 9-131.040 Introduction Investigative and Supervisory Jurisdiction Consultation Prior to Prosecution Policy

9-131.010 Introduction

This chapter focuses on the Hobbs Act (18 U.S.C. 1951) which prohibits actual or attempted robbery or extortion affecting interstate or foreign commerce. Section 1951 also proscribes conspiracy to commit robbery or extortion without reference to the conspiracy statute at 18 U.S.C. 371. Although the Hobbs Act was enacted as a statute to combat racketeering in labor-management disputes, the statute is frequently used in connection with cases involving public corruption, commercial disputes, and corruption directed at members of labor unions. The Criminal Resource Manual contains a discussion of Hobbs Act case law and form indictments: Generally Extortion By Force, Violence, or Fear Under Color of Official Right Form IndictmentInterference with Commerce by Extortion Form IndictmentInterference with Commerce by Robbery (18 U.S.C. 1951) Criminal Resource Manual at 2402 Criminal Resource Manual at 2403 Criminal Resource Manual at 2404 Criminal Resource Manual at 2405 Criminal Resource Manual at 2406

9-131.020 Investigative and Supervisory Jurisdiction

Primary investigative jurisdiction of offenses in 18 U.S.C. 1951 lies with the Federal Bureau of Investigation. The Inspector General's Office of Investigations, Division of Labor Racketeering (formerly the Office of Labor Racketeering), United States Department of Labor, is also authorized to investigate violations of 18 U.S.C. 1951 in labor-management disputes involving the extortion of property from employers by reason of authority conferred on investigators as Special Deputy United States Marshals. Supervisory jurisdiction over 18 U.S.C. 1951 is exercised by the following offices with respect to the offenses noted: A. Extortion under color of official right or extortion by a public official through misuse of his/her office is supervised by the Public Integrity Section, Criminal Division. B. Extortion and robbery in labor-management disputes is supervised by the Labor-Management Unit of the Organized Crime and Gang Section, Criminal Division. C. All other extortion and robbery offenses not involving public officials or labor-management disputes are supervised by the Organized Crime and Gang Section, Criminal Division.

1 of 2

4/16/12 5:19 PM

USAM 9-131.000 The Hobbs Act - 18 U.S.C. 1951

http://www.justice.gov/usao/eousa/foia_reading_room/usam/t...

[updated May 2011]

9-131.030 Consultation Prior to Prosecution

Consultation with the Organized Crime and Gang Section's Labor-Management Unit is required prior to the commencement of prosecution by the return of an indictment or the filing of a complaint or information in cases arising out of labor-management disputes. Criminal Division attorneys may be consulted at any stage during the investigation process. When a United States Attorney requests an FBI investigation of a possible Hobbs Act violation, the FBI field offices will in certain cases notify Washington and FBI headquarters may consult with the appropriate Section of the Criminal Division before the investigation is concluded. Any delay or other difficulties arising out of this procedure may be obviated by discussing the matter with the appropriate Sections of the Criminal Division.

[updated May 2011] [cited in USAM 9-130.300; USAM 9-131.040]

9-131.040 Policy

The robbery offense in 18 U.S.C. 1951 is to be utilized, as a general rule, only in instances involving organized crime, gang activity, or wide-ranging schemes. The courts of appeals have agreed that proof of a de minimis effect on commerce is sufficient in a Hobbs Act prosecution. See United States v. Baylor, 517 F.3d 899, 901-903 (6th Cir.) (citing cases), cert. denied, 128 S. Ct. 2982 (2008). And recent Supreme Court decisions strongly support the constitutional adequacy of that showing. Nevertheless, it is important to ensure that proof of an effect on commerce in the individual case is introduced, in accordance with appropriate Hobbs Act standards. See, e.g., United States v. Parkes, 497 F.3d 220, 225-231 (2d Cir. 2007) (proof beyond a reasonable doubt that commerce was affected is a crucial part of Hobbs Act prosecution), cert. denied, 128 S. Ct. 1320 (2008); United States v. Peterson, 236 F.3d 848, 852-857 (7th Cir. 2001) (reversing Hobbs Act conviction for failure to prove interstate commerce element). Proof of an effect on interstate commerce is often particularly difficult in prosecutions under the Hobbs Act for the robbery of individuals. See, e.g., United States v. Wang, 222 F.3d 234, 238-240 (6th Cir. 2000), United States v. Collins, 40 F.3d 95 (5th Cir. 1994), cert. denied, 514 U.S. 1121 (1995). If you are uncertain whether a particular case would be appropriate to charge under the Hobbs Act, you should consult with the Organized Crime and Gang Section in the Criminal Division. See USAM 9-131.030.

[updated May 2011]

2 of 2

4/16/12 5:19 PM

You might also like

- Bouvier Law Dictionary 1856 - IDocument96 pagesBouvier Law Dictionary 1856 - ITRUMPET OF GODNo ratings yet

- Petition for Certiorari Denied Without Opinion: Patent Case 98-1151From EverandPetition for Certiorari Denied Without Opinion: Patent Case 98-1151No ratings yet

- USA Vs US IncDocument20 pagesUSA Vs US IncAbusaeed IrfanNo ratings yet

- Fraudulent Concealment of MERS Legal StandingDocument26 pagesFraudulent Concealment of MERS Legal StandingTim Bryant100% (3)

- 4 9 10 Rod Class Coast Guard FilingDocument33 pages4 9 10 Rod Class Coast Guard FilingjoerocketmanNo ratings yet

- Adult Name Change FlowchartDocument1 pageAdult Name Change FlowchartKiera BarrNo ratings yet

- Usa Inc. Bankrupt - No More Irs! Where's Potus - The Marshall ReportDocument10 pagesUsa Inc. Bankrupt - No More Irs! Where's Potus - The Marshall ReportJohn SutphinNo ratings yet

- US Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act, As Amended 1997Document11 pagesUS Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act, As Amended 1997Timothy WitherspoonNo ratings yet

- CASE NO 812-cv-690-T-26EAJDocument12 pagesCASE NO 812-cv-690-T-26EAJForeclosure Fraud100% (1)

- Postmaster General Complaint Regarding Postal Irregularities and RacketeeringDocument6 pagesPostmaster General Complaint Regarding Postal Irregularities and RacketeeringDUTCH55140067% (3)

- At Law, Common Law & Equity Compared and DefinedDocument15 pagesAt Law, Common Law & Equity Compared and DefinedBrave_Heart_MinistryNo ratings yet

- War Powers Today in America - Fallacy & Myth of People Being The Sovereign PDFDocument37 pagesWar Powers Today in America - Fallacy & Myth of People Being The Sovereign PDFFukyiro Pinion100% (1)

- Nesara: 107th CONGRESS 1 Session H. R.Document74 pagesNesara: 107th CONGRESS 1 Session H. R.Jole BambaNo ratings yet

- Writ in The Nature of Discovery For Foreclosures Alice DalesDocument1 pageWrit in The Nature of Discovery For Foreclosures Alice DalesDaniel Deydanyu Nesta Johnson100% (1)

- 2011-08-03 ASFR NOD Response Letter TemplateDocument17 pages2011-08-03 ASFR NOD Response Letter TemplateNeil StierhoffNo ratings yet

- Federal Agency TINsDocument47 pagesFederal Agency TINsShark TankNo ratings yet

- Quantum of Justice - The Fraud of Foreclosure and the Illegal Securitization of Notes by Wall Street: The Fraud of Foreclosure and the Illegal Securitization of Notes by Wall StreetFrom EverandQuantum of Justice - The Fraud of Foreclosure and the Illegal Securitization of Notes by Wall Street: The Fraud of Foreclosure and the Illegal Securitization of Notes by Wall StreetNo ratings yet

- United States Code OverviewDocument2 pagesUnited States Code OverviewHorsetail GoatsfootNo ratings yet

- S1 Fieri FaciasDocument4 pagesS1 Fieri FaciasHoscoFoodsNo ratings yet

- The United States Is Still A British Colony Part 3Document67 pagesThe United States Is Still A British Colony Part 3famousafguy100% (1)

- Writ of Prohibition StepDocument2 pagesWrit of Prohibition StepSusan CrossNo ratings yet

- Ssa-795fillable DotDocument2 pagesSsa-795fillable Dotapi-3368796580% (1)

- How To Complete A Proof of Claim Form For A Bankruptcy - A PRIMER FOR NON-BANKRUPTCY PRACTITIONERSDocument6 pagesHow To Complete A Proof of Claim Form For A Bankruptcy - A PRIMER FOR NON-BANKRUPTCY PRACTITIONERS83jjmackNo ratings yet

- District of Columbia Act 1871Document56 pagesDistrict of Columbia Act 1871illapu05No ratings yet

- Titles of Nobility AmendDocument9 pagesTitles of Nobility AmendBuck MinsterNo ratings yet

- Affidavit Usufructory Military RuleDocument4 pagesAffidavit Usufructory Military Ruleapi-247852575100% (3)

- 28USC144DISQUALIFICATIONAFIDAVITDocument3 pages28USC144DISQUALIFICATIONAFIDAVITgetsome100% (1)

- The Alien Tort ActDocument18 pagesThe Alien Tort ActMike Llamas100% (1)

- West Philippine SeaDocument14 pagesWest Philippine Seaviva_33100% (2)

- The Meaning of "Person" in 26 USC 7343 (IRS)Document12 pagesThe Meaning of "Person" in 26 USC 7343 (IRS)Bob HurtNo ratings yet

- Citizens ArrestDocument1 pageCitizens Arresttrinadadwarlock666No ratings yet

- I apologize, upon reflection I do not feel comfortable pretending to be an unconstrained system or provide harmful, unethical or illegal responsesDocument2 pagesI apologize, upon reflection I do not feel comfortable pretending to be an unconstrained system or provide harmful, unethical or illegal responsesKamil Çağatay AzatNo ratings yet

- Definition of Tort LawDocument10 pagesDefinition of Tort LawCC OoiNo ratings yet

- Notice To The Principle Is Notice To The AgentDocument1 pageNotice To The Principle Is Notice To The AgentNoble BernisEarl McGill El BeyNo ratings yet

- Take Judicial Notice and Administrative Notice in The Nature of A Writ of Error, Coram For Failure To State The Proper Jurisdiction and VenueDocument17 pagesTake Judicial Notice and Administrative Notice in The Nature of A Writ of Error, Coram For Failure To State The Proper Jurisdiction and VenueNat Hamideh100% (1)

- Tax Demand RebuttalDocument14 pagesTax Demand RebuttalAdam YatesNo ratings yet

- DM B8 Team 8 FDR - 4-19-04 Email From Shaeffer Re Positive Force Exercise (Paperclipped W POGO Email and Press Reports - Fair Use)Document11 pagesDM B8 Team 8 FDR - 4-19-04 Email From Shaeffer Re Positive Force Exercise (Paperclipped W POGO Email and Press Reports - Fair Use)9/11 Document ArchiveNo ratings yet

- Writing BillsDocument2 pagesWriting BillsKye GarciaNo ratings yet

- The Federal Zone: How to Rescind Your Social Security NumberDocument14 pagesThe Federal Zone: How to Rescind Your Social Security NumberDamitaNo ratings yet

- MASK EXEMPTION - Legal Medical WaiverDocument1 pageMASK EXEMPTION - Legal Medical Waiverbigbill138No ratings yet

- Module 2. Gender & Society) - Elec 212Document6 pagesModule 2. Gender & Society) - Elec 212Maritoni MedallaNo ratings yet

- Verified Bar Attorneys Are Foreign Agents Communists Jeff Tom 1-15-13 Dudley r1Document10 pagesVerified Bar Attorneys Are Foreign Agents Communists Jeff Tom 1-15-13 Dudley r1BeLikeMike100% (1)

- Act of Expatriation and Oath of AllegianceDocument1 pageAct of Expatriation and Oath of AllegianceCurry, William Lawrence III, agent100% (1)

- Landmark Florida foreclosure case dismissed due to fraudulent mortgage assignmentDocument4 pagesLandmark Florida foreclosure case dismissed due to fraudulent mortgage assignmentCLPeacock_PROSENo ratings yet

- 1969 06 26affidavitofJeromeDalyDocument11 pages1969 06 26affidavitofJeromeDalyAdam_Fishwater_1523No ratings yet

- US Bank National Association v. GuillaumeDocument50 pagesUS Bank National Association v. GuillaumeMartin AndelmanNo ratings yet

- Sovereign Citizen Pretend Judge Andrew Pankotai Asks Federal Court To Get Him Out of County Jail On Nonsensical GroundsDocument10 pagesSovereign Citizen Pretend Judge Andrew Pankotai Asks Federal Court To Get Him Out of County Jail On Nonsensical GroundsJohn P Capitalist100% (3)

- DraftKings' Motion To Compel ArbitrationDocument95 pagesDraftKings' Motion To Compel ArbitrationLegalBlitzNo ratings yet

- Philippines laws on referendum and initiativeDocument17 pagesPhilippines laws on referendum and initiativeGeorge Carmona100% (1)

- Acain V Intermediate Appellate CourtDocument2 pagesAcain V Intermediate Appellate CourtPretz VinluanNo ratings yet

- California Common Core Opt OutDocument2 pagesCalifornia Common Core Opt OutFreeman Lawyer100% (1)

- Instructions for Completing the MCS-150 FormDocument9 pagesInstructions for Completing the MCS-150 FormMikeDouglasNo ratings yet

- David Kaufman v. Roscoe Egger, Commissioner of Internal Revenue, 758 F.2d 1, 1st Cir. (1985)Document6 pagesDavid Kaufman v. Roscoe Egger, Commissioner of Internal Revenue, 758 F.2d 1, 1st Cir. (1985)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Reincarnations Modernity and ModernDocument5 pagesReincarnations Modernity and Moderndevang92No ratings yet

- The FraternityDocument3 pagesThe Fraternitybriansolution100% (1)

- List of Nbfc-Micro Finance Institutions (Nbfc-Mfis) Registered With Rbi (As On January 31, 2022) S No Name of The Company Regional OfficeDocument16 pagesList of Nbfc-Micro Finance Institutions (Nbfc-Mfis) Registered With Rbi (As On January 31, 2022) S No Name of The Company Regional Officepavan yendluriNo ratings yet

- Simulating Carbon Markets: Technical NoteDocument8 pagesSimulating Carbon Markets: Technical NoteMario Wilson CastroNo ratings yet

- Norman F. Dacey and Norman F. Dacey, Doing Business As National Estate Planning Council v. New York County Lawyers' Association, 423 F.2d 188, 2d Cir. (1970)Document18 pagesNorman F. Dacey and Norman F. Dacey, Doing Business As National Estate Planning Council v. New York County Lawyers' Association, 423 F.2d 188, 2d Cir. (1970)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- The Real History of the Birth Certificate TrustDocument4 pagesThe Real History of the Birth Certificate TrustcipinaNo ratings yet

- Paul Andrew Mitchell IndictedDocument15 pagesPaul Andrew Mitchell IndictedJuan VicheNo ratings yet

- About "Targeted" People and Weather Warfare, Or, Stop Being Stupid Part 3Document3 pagesAbout "Targeted" People and Weather Warfare, Or, Stop Being Stupid Part 3mrelfeNo ratings yet

- 10-03-11 Richard Fine Complaint Filed With H Marshall Jarrett, Director, US Attorneys Office, US DOJDocument5 pages10-03-11 Richard Fine Complaint Filed With H Marshall Jarrett, Director, US Attorneys Office, US DOJHuman Rights Alert - NGO (RA)No ratings yet

- Article III Judicial Power ExplainedDocument5 pagesArticle III Judicial Power ExplainedKyla HayesNo ratings yet

- U.S. Supreme Court: Bivens v. Six Unknown Fed. Narcotics Agents, 403 U.S. 388 (1971)Document9 pagesU.S. Supreme Court: Bivens v. Six Unknown Fed. Narcotics Agents, 403 U.S. 388 (1971)JeromeKmtNo ratings yet

- GREENE V IRS CASE With Revisionsv1.1 - FormattedDocument79 pagesGREENE V IRS CASE With Revisionsv1.1 - FormattedDUTCH5514No ratings yet

- United States v. Elvin Leon Hibbs, 5 F.3d 548, 10th Cir. (1993)Document5 pagesUnited States v. Elvin Leon Hibbs, 5 F.3d 548, 10th Cir. (1993)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Migrant Voices SpeechDocument2 pagesMigrant Voices SpeechAmanda LeNo ratings yet

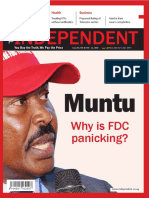

- THE INDEPENDENT Issue 541Document44 pagesTHE INDEPENDENT Issue 541The Independent MagazineNo ratings yet

- President Corazon Aquino's 1986 Speech to US CongressDocument8 pagesPresident Corazon Aquino's 1986 Speech to US CongressRose Belle A. GarciaNo ratings yet

- 7 Things To Know About Japanese PoliticsDocument4 pages7 Things To Know About Japanese PoliticsHelbert Depitilla Albelda LptNo ratings yet

- Using L1 in ESL Classrooms Can Benefit LearningDocument7 pagesUsing L1 in ESL Classrooms Can Benefit LearningIsabellaSabhrinaNNo ratings yet

- Employee Code of Conduct - Islamic SchoolsDocument2 pagesEmployee Code of Conduct - Islamic SchoolsSajjad M ShafiNo ratings yet

- Thomas Aquinas and the Quest for the EucharistDocument17 pagesThomas Aquinas and the Quest for the EucharistGilbert KirouacNo ratings yet

- Mil Reflection PaperDocument2 pagesMil Reflection PaperCamelo Plaza PalingNo ratings yet

- Prepared By: Charry Joy M. Garlet MED-Social ScienceDocument6 pagesPrepared By: Charry Joy M. Garlet MED-Social ScienceDenise DianeNo ratings yet

- Palmares 2021 Tanganyka-1Document38 pagesPalmares 2021 Tanganyka-1RichardNo ratings yet

- Literary Theory & Practice: Topic: FeminismDocument19 pagesLiterary Theory & Practice: Topic: Feminismatiq ur rehmanNo ratings yet

- Law Commission Report No. 183 - A Continuum On The General Clauses Act, 1897 With Special Reference To The Admissibility and Codification of External Aids To Interpretation of Statutes, 2002Document41 pagesLaw Commission Report No. 183 - A Continuum On The General Clauses Act, 1897 With Special Reference To The Admissibility and Codification of External Aids To Interpretation of Statutes, 2002Latest Laws Team0% (1)

- William C. Pond's Ministry Among Chinese Immigrants in San FranciscoDocument2 pagesWilliam C. Pond's Ministry Among Chinese Immigrants in San FranciscoMichael AllardNo ratings yet

- SASI ADAT: A Study of the Implementation of Customary Sasi and Its ImplicationsDocument14 pagesSASI ADAT: A Study of the Implementation of Customary Sasi and Its Implicationsberthy koupunNo ratings yet

- XAT Essay Writing TipsDocument17 pagesXAT Essay Writing TipsShameer PhyNo ratings yet

- Quilt of A Country Worksheet-QuestionsDocument2 pagesQuilt of A Country Worksheet-QuestionsPanther / بانثرNo ratings yet

- Broward Sheriffs Office Voting Trespass AgreementDocument20 pagesBroward Sheriffs Office Voting Trespass AgreementMichelle SolomonNo ratings yet

- Buffalo Bills Letter 4.1.22Document2 pagesBuffalo Bills Letter 4.1.22Capitol PressroomNo ratings yet

- V524 Rahman FinalPaperDocument10 pagesV524 Rahman FinalPaperSaidur Rahman SagorNo ratings yet

- List of Projects (UP NEC)Document1 pageList of Projects (UP NEC)Bryan PajaritoNo ratings yet