Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Caballero 2007, Motion Verbs in Wine Description

Uploaded by

lilongaOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Caballero 2007, Motion Verbs in Wine Description

Uploaded by

lilongaCopyright:

Available Formats

Journal of Pragmatics 39 (2007) 20952114 www.elsevier.

com/locate/pragma

Manner-of-motion verbs in wine description

Rosario Caballero *

Departamento de Filologia Moderna, Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha, Avenida Camilo Jose Cela s/n, 13071 Ciudad Real, Spain Received 16 May 2006; received in revised form 16 October 2006; accepted 23 July 2007

Abstract Manner-of-motion verbs are frequently used in English narratives to portray motion events in vivid terms. This use of motion verbs contrasts with their use in non-narrative texts where the verbs are used to qualify static entities, and often instantiate gurative phenomena. The present paper explores the use of motion verbs in the descriptive-plus-evaluative genre of the wine tasting note. The discussion draws upon the results of an ongoing research project dealing with gurative language in wine discourse, and is theoretically anchored in research done in cognitive linguistics. My goals in this paper are two: on the one hand, I describe the way the expressions are used in the genre and the reasons underlying this use; on the other, I discuss the gurative motivation of the motion verbs in the genre under analysis, particularly their reliance on synesthetic metaphor and metonymy, respectively. # 2007 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Manner-of-motion verbs; Winespeak; Genre; Fictive motion; Synesthesia; Metonymy

1. Introduction Manner-of-motion verbs are ubiquitous in English narratives where they help authors portray motion events in vivid terms and presumably help readers picture the scene thus expressed. Apart from this prototypical use, the verbs can also be found predicating static rather than dynamic entities. This is the case of sentences like Main Street winds from one end of town to the other or an amphitheater-like arrangement that fans out from the base of the building, where wind and fan out are used to describe spatial ensembles as if moving although they concern static scenarios. In this paper I discuss the use of manner-of-motion verbs in a non-narrative and largely unexplored context, namely, the wine tasting note, where expressions like earthy avors run through this rm-textured red or hints of milk chocolate and vanilla sneak in on the palate are

* Tel.: +34 926 295300x3128; fax: +34 926 295312. E-mail address: MRosario.Caballero@uclm.es. 0378-2166/$ see front matter # 2007 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved. doi:10.1016/j.pragma.2007.07.005

2096

R. Caballero / Journal of Pragmatics 39 (2007) 20952114

far from unusual. I am particularly concerned with exploring the pragmatic reasons underlying the use of such patterns in the description of wines aroma(s), avor(s), and mouthfeel in the genre. However, since none of those traits actually i.e. literally move, attention will also be paid to the gurative motivation of the expressions. The paper is organized as follows: after a brief survey of approaches to the non-narrative use of motion verbs, I describe the way such verbs are used in the tasting note genre and the reasons motivating this use. This is followed by a discussion on the gurative motivation of the verbs in this specic instance of wine discourse. 2. Narrative versus non-narrative uses of motion verbs The lexicalization of manner in the main verb of a clause is a conspicuous characteristic of languages like English, and nowhere is this better illustrated than in motion verbs. The richness of the English lexicon in this respect has been pointed out by numerous scholars, and has given rise to a vast amount of research broadly driven by two types of concern. One line of research has dealt with the topic by framing it within the discussion on the semantic properties of verbs and their effect on the syntactic behavior of verbal patterns (Fillmore, 1968, 1977; Lehrer, 1974; Guerssel et al., 1985; Jackendoff, 1990; Van Valin, 1990; Dowty, 1991; Levin and Rappaport Hovav, 1992; Levin, 1993; Tenny, 1994; Kaufmann, 1995; Goldberg, 1998; Rappaport Hovav and Levin, 1998; inter alia). A second line of research has approached the phenomenon from a typological or contrastive perspective, and has explored how motion is expressed in languages such as Basque (Ibarretxe` Antunano, 2004, 2006), Japanese (Kita, 1997, 1999), French versus Germanic languages (Tesniere, 1957/1994; Vinay and Darbelnet, 1958; Malblanc, 1968; Wandruszka, 1976), and Spanish versus English (Slobin, 1996, 2004; Mora Gutierrez, 2001; Morimoto, 2001), to list but a few of the languages under survey. The differences across languages in this respect have led Talmy (1983, 1985, 1988, 1991) to build up a typology where languages fall into one of two categories: what he calls satellite-framed languages (e.g. Germanic languages) and verb-framed languages (e.g. Romance languages) according to whether the trajectory or path of movement is lexicalized as a satellite of the main verb in the clause or in the verb itself (English go up versus Spanish subir). Another conspicuous difference between languages of both types is the lexicalization of manner in verbs of satellite-framed languages in contrast with the tendency in verb-framed languages to express manner via verb complementation (e.g. tiptoe out versus salir de puntillas). The research briey outlined has focused on the default use of motion patterns to designate physical actions (typically, in narrative texts). However, such expressions do not always convey actual displacements from one place to another, but are also often used to describe static scenes and entities. By way of illustration, consider the following passages: (1) (2) (3) He tumbled with Roberts, helpless and in agony, over and over, down the steps. [Narrative. Brown Corpus] A stair tumbles down from this rst oor incision onto the man-made island. [Wall Games. Architectural review from Architecture Australia 88 (2)] A lush, seductive, opulent mouthful of berry, plum and spice avors that practically tumble over each other before harmonizing on the long nish. [Tasting note from Wine Spectator]1

1 Tasting notes were retrieved from both printed and online sources. Since in the latter case tasting notes are usually classied according to wine type and region, the magazine issue where they were originally published in paper format is unknown.

R. Caballero / Journal of Pragmatics 39 (2007) 20952114

2097

Whereas tumble in (1) describes actual motion, in (2) and (3) the verb is used to articulate the sensory visual and taste experiences afforded by a spatial arrangement and a wine, respectively. Yet only the locational use of motion verbs exemplied in (2) has called the attention of scholars, who have explained it according to their different rationales. On the one hand, the dynamic predication of otherwise static scenes and entities has been addressed by cognitive linguists. Thus, in Lakoff and Turner (1989:142144), they are regarded as particular instances of the metaphor FORM IS MOTION whereby our understanding and verbalization of certain spatial arrangements and topologies rests upon particular ways of moving. In other words, according to their denition of metaphor as mapping knowledge across two disparate experiential domains, the locational use of motion patterns is explained as motivated by a metaphor where motion is mapped onto form or shape. Other cognitive scholars have framed the phenomenon within the broader notion variously referred to as ctive motion (Talmy, 1983, 1985, 1996, 2000; Matclock, 2004), abstract motion (Langacker, 1986, 1987), and subjective motion (Matsumoto, 1996), a notion that is not always seen as metaphorically motivated. Thus, for Langacker a sentence like Highway A3 runs from Valencia to Madrid does not instantiate a mapping from a spatial domain to a non-spatial domain, but designates a particular spatial conguration as this is dynamically construed by the speaker/writer. This construal invokes a road seen or proled in full, that is, imagined and verbalized through the simultaneous activation of every single location in its spatiotemporal base. The expression conveys a certain sense of motion, but this does not imply the presence of a metaphorical mapping from a motion domain onto a spatial one. In contrast with Langackers views, Talmy (1996) suggests that ctive motion expressions concerned with spatial descriptions are metaphorically motivated regardless of whether they evoke actual motion for every speaker. By framing the expressions within the broader notion of ception (which encompasses both perception and conception), Talmys views bring to mind Lakoff and Turners FORM IS MOTION metaphor briey outlined earlier, while drawing attention to the perceptual visual plus conceptual quality of the phenomenon.2 In turn, Functional Systemic linguists have provided a more rhetorically biased explanation of this specic use of motion patterns (Halliday, 1985/1994; Eggins, 1994; Thompson, 1996; Martin et al., 1997). The main postulate is that language users may choose between two different ways of construing the semantic notion of location: relationally i.e. statically by means of verbs typically used to convey relations and states such as be, or dynamically by means of verbs of doing e.g. motion verbs. Thus, Thompson (1996:81) explains the use of run in the sentence Hope Street runs between the two cathedrals as a case of blending in which the relational (state) meaning is dominant but the wording brings in a material (action) process colouring. The choice of a motion verb is attributed to the rhetorical demands imposed on authors, who may seek a more dynamic tone in their descriptions especially if there are a number of similar choices in that area of the text. This explanation implies that the use of a motion verb is subservient to various textual considerations and, therefore, may well be dispensable rather than being the natural or rst option. In the present paper I describe wine critics use of verbs like burst, emerge, come, jump, run, weave, glide, pop, leap or creep to describe the olfactory, gustatory, and tactile properties of wine in tasting notes (TNs henceforth). The main hypothesis is that this use is highly determined by the

2

For a discussion of motion patterns in the description of built arrangements see Caballero (2006, in press).

2098

R. Caballero / Journal of Pragmatics 39 (2007) 20952114

idiosyncrasy of a genre concerned with verbalizing the organoleptic sensations produced by that drink. As will be seen, wine tasting procedures follow a canonical order which is reected in the genre, and this appears to underlie critics choice of certain verbs in communicating what wines smell, taste and feel like. A related issue is the fact that wine is not a static entity, but changes from the very moment that a bottle is opened and the wine sits in the glass a dynamism also reected in the use of motion patterns concerned with describing that evolution. However, explaining the use of motion verbs as solely subservient to rhetorical issues might diminish their heuristic role in overcoming the difculties involved in expressing sensory perception. For real motion experiences as evoked by the verbs used to articulate them help critics construe experiences accessed via such disparate senses as taste, smell and touch. This cutting across the senses suggests that, as happens with the dynamic rendering of spatial congurations briey outlined earlier, their use may also be motivated by gurative phenomena of different sorts. Before taking this point further, let us look at the genre where the verbs are used. 3. The tasting note The present paper draws upon the results of the ongoing research project Translating the senses: Metaphor in winespeak devoted to exploring the gurative language used by wine critics in TNs,3 and drawing upon the cognitive approach to metaphor rst expounded in Lakoff and Johnson (1980). In order to do so, we built a corpus consisting of 12,000 TNs of both red and white wines (6000 of each), written by the most authoritative British and American voices in the eld, and retrieved from well-known wine magazines and websites. For the purposes of this paper, however, only a section of the corpus has been used. This consists of 6000 TNs (74,832 words) retrieved from Wine Enthusiast, Wine Spectator, and Wine Advocate. TNs are extremely short texts (from 10 to 100 words) devoted to describing and evaluating wines. The genre is the verbal counterpart of the highly ritualized event of wine tasting, as explained by Silverstein (2004:641) in the following terms: For wine, the actual aesthetic object is approached in phases or stages, along an ordered structure of dimensionalities of perceptual encounter, with a peak or seemingly closest stage toward which and away from which all the other stages seem to proceed. [. . .] What we nd is that the tasting note does, indeed, have a mimetic or iconic textual form, in which the descriptors in text-time in general move along as though presupposing the ritualized organization of the tasting encounter. Accordingly, the bulk of the genres structure rests in three distinct sections that follow the three main steps in wine tasting, namely, the description and assessment of (a) a wines color, (b) its smell, metonymically referred to as the wines nose, and (c) the impressions of the wine in the tasters mouth, covering the wines avor(s) and texture and metonymically referred to as the wines palate. The prototypical structure of TNs is schematized in Table 1. (For a similar, albeit less detailed description, see Silverstein, 2004).

Project nanced by the Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha (Spain).

R. Caballero / Journal of Pragmatics 39 (2007) 20952114 Table 1 Rhetorical organization of tasting notes Technical card (optional) Introduction of the wine Name and year Winery Price Score Cases/bottles made Grape composition First evaluation of wine Assessment of the wines color Assessment of the wines nose (aroma + bouquet) Assessment of the wines palate (avors and texture or mouthfeel) Attack Mid-palate Aftertaste or nish Closing evaluation of the wine Potential consumers Consumption span Recommended food Final evaluation and/or and/or and/or and/or and/or and/or and/or and/or

2099

and/or and/or and/or

What follows is a typical TN: (4) The 2003 Vitiano, a blend of Merlot, Sangiovese, and Cabernet, fared better in the vintage, and the wine is undoubtedly one of the best made to date. Blackish in color, intense in its expression of berry fruit and herbs, tarry and long on the palate, and with considerable length and bite on the nish. It too will continue to drink well for another 34 years.

Research on the language used by wine critics/tasters (winespeak or, in Silversteins terms, oinoglossia) has mainly addressed two issues, namely, (a) the need to reconcile the inherently subjective quality of wine tasting with the mastering of objective descriptors recognized and shared by all the members in the highly heterogeneous community formed around wine, and (b) the gurative quality of wine commentary. What may be referred to as the subjectivity-objectivity dichotomy characterizing winespeak has been approached from different perspectives. Some voices within the wine realm have pointed to the need to develop a standardized terminology if wine tasting wants to reach a scientic or reliable status (Noble et al., 1987; Bernstein, 1998; Pierre, 1998; Moore, 1999; Gawel and Oberholster, 2001; Gregutt, 2003; Nedlinko, 2006). Other scholars have focused on the difculties inherent in organoleptic perception and the concomitant difculties in articulating the visual, olfactory and gustatory properties of wines. The emphasis has been mostly placed on exploring the differences between novices commentary and that of wine experts according to the range of sensory experiences and capacity to memorize them exhibited by both groups and their ability to use standardized descriptors to communicate them (Lehrer, 1983, 1992; Lawless, 1984; Solomon, 1990, 1997; Gawel, 1997; Hughson and Boakes, 2001).

2100

R. Caballero / Journal of Pragmatics 39 (2007) 20952114

Another salient characteristic of critics language as conspicuously illustrated in TNs is its heavy reliance on imagery. Given the shortage of terms available to articulate smell and taste experiences, their verbalization usually makes use of (a) metonymical expressions which allude either to discrete entities or to one of their characteristics (ripe aromas, apple avor), (b) similes (wines that taste or smell like a fruit cocktail), (c) terms borrowed from other sensory experiences (wines that smell sweet), and (d) metaphorical language (wines described as fortied, tightly-knit, or broad-shouldered, and qualied as shy, monolithic, or square). Indeed, spotting apple and slate in a white wine, or cranberries and tar in a red one is one thing, but describing their tactile impression on our palate, their size, or their length is a different matter, and nearly always demands the use of gurative language. However, of all the aspects related to wine terminology, the gurative motivation of critics language has received less attention than expected most discussion focusing on the use of aroma, avor and texture descriptors such as oral, clean, varietal, dry, fresh or crisp (see, for instance, Ann Nobles famous Wine Aroma Wheel). What is surprising in this discussion is that no mention is made of the gurative quality of many of these descriptors. This is the case of dry or crisp, which are metaphorical in the sense that they prototypically belong either to sensory modes different from smell or avor (typically, touch), or to domains of experience other than wine (e.g. architecture, as suggested by terms such as monolithic or fortied), and this transfer or mapping across unrelated experiences is what cognitive phenomena like metaphor are about (Lakoff and Johnson, 1980; Lakoff, 1993; Gibbs, 1994). A few scholars have nevertheless paid attention to the metaphors in wine commentary either to criticize their use (Gluck, 2003; Peynaud, 1987) or to highlight their heuristic, indispensable role in wine assessment (Amoraritei, 2002; Lehrer, 1983, 1992, in press). Concerning the latter position, in Amoraritei (2002) we nd a detailed description of how the metaphor WINES ARE PEOPLE pervades the language of French critics, particularly in describing the structural and personality traits of wine the former effected by means of terms such as corps (body), charnu (eshy) or maigre (thin), and the latter conveyed via adjectives such as agressif (aggressive), reserve (demure or shy), or aimable (suave).4 In turn, Lehrer (in press) makes a revision of her previous work, and discusses lexis also drawing upon the domains of architecture, botany, artifact production, or music, while noting that such language not only shows the high degree of linguistic creativity currently exhibited by wine critics, but points to the weight of cognitive processes in language use. A case in point of the creativeness characterizing wine critics language is their use of motion verbs in TNs. In fact, the verb-less quality of the texts makes the presence of such verbs all the more conspicuous, as shown in the following note: (5) A racy young wine, with lots of class. Starts slowly on the palate, then kicks in with tight and pronouncedly silky tannins.

This dynamic rendering of wines has hitherto been unexplored by those scholars dealing with the metaphors in winespeak, which is odd since describing wines as entities capable of moving is fully compatible with the aforementioned view of wines as PEOPLE. However, only one third of the motion instances found in the corpus predicate wines as a whole, all other instances being concerned with their nose and palate. This suggests that, although some motion patterns might be

4

These terms are also widely used by Spanish and English critics.

R. Caballero / Journal of Pragmatics 39 (2007) 20952114

2101

seen as illustrating the pervasiveness of the aforementioned anthropomorphic schema in wine discourse, other factors need to be taken into account as well to explain critics use of motion verbs. In the following section, I describe the verbs commonly found in TNs, the meanings they help express, and their role in the genre. 4. Motion patterns in TNs The corpus yielded 665 instances (i.e. tokens) where wines or some of their properties are rendered in dynamic rather than static terms. These comprise the following 50 verb types ordered according to frequency of occurrence: explode (102), burst (77), come (56), start (55), emerge (49), go (40), unfold (31), swirl (22), jump (20), kick (18), run (17), weave (14), glide (13), cascade (11), way patterns (10), ride (9), extend (9), oat (8), dance (8), pour (8), begin (8), fold (7), pump (7), sneak (6), segue (6), gush (5), pop (5), ooze (4), leap (4), shoot (4), move (4), swim (3), fan out (3), creep (3), course (2), erupt (2), tumble (2), converge (1), dip (1), punch (1), race (1), sail (1), sally forth (1), spin (1), stretch (1), toss up (1), bob (1), branch out (1), zip (1), unfurl (1) Of course, not all these verbs are motion verbs proper. Thus, whereas come, go, move, ride, swim, run, jump, creep or sally forth denote change of location, verbs such as unfold, stretch or unfurl are mainly concerned with change of state, and the core meaning of kick or punch is contact by impact (see Levin, 1993 for a thorough classication of verbs according to their semantic and syntactic behavior). However, all of them are characterized by the fact that motion is also part and parcel of their semantics irrespective of whether this is the core meaning or conates with other notions. Moreover, some such verbs occur with motion particles. A case in point is verbs of contact by impact like kick and punch, which always occur in TNs with in, off, up and through which turn them into motion verbs proper. Therefore, all the verbs listed above were considered worthy of consideration for the purposes of this paper, and regarded as motion verbs. As already pointed out, the verbs are used to describe and evaluate wines as a whole, their nose, and their palate (the latter comprising avor(s) and mouthfeel). Thus, of all the motion data in the corpus, 292 instances (44%) occur with the term wine, 300 instances (45%) occur with terms such as avor(s), texture, nish, oak, fruit, or tannins (all of them belonging to the wines palate),5 and 73 instances (11%) occur with aroma(s), scent(s), or bouquet (i.e. the wines nose). 4.1. Type and meaning of motion patterns in TNs A closer look at the verbs above reveals that most of them incorporate the notion of manner in their semantics. However, manner is not a unitary concept: among other things, it may refer to the motor properties of motion (walk versus crawl), rate (walk versus run), attitude (walk versus stroll), or the medium where motion is effected (walk versus swim). Accordingly, manner-of-motion verbs have been further classied in the cognitive literature according to

5 As happens with palate, critics use of terms such as the fruit or oak in a wine does not mean that these are actually present in it. Rather, the terms refer to the avors resulting from those elements throughout the wines ageing process as perceived in the tasters mouth.

2102

R. Caballero / Journal of Pragmatics 39 (2007) 20952114

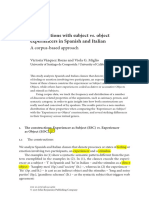

such semantic categories as energy (e.g. stride), forced motion (e.g. drag), furtive motion (e.g. sneak), motor pattern (e.g. walk, jump or y verbs), obstructed motion (e.g. tumble), rate (e.g. bolt), and smooth motion (e.g. slide). (For a detailed discussion on the differences of manner in motion verbs see Slobin, 1996, 2000; Ozcaliskan, 2004; Ibarretxe-Antunano, 2006.)6 These categories may be also applicable to the verbs found in TNs, provided that we bear in mind that here manner is not concerned with actual motion but, rather, with organoleptic perception, particularly perception via nose and mouth. This is a complex phenomenon that mostly relies upon two variables or dimensions, namely, intensity and persistence. Both are particularly relevant in the assessment of wines in TNs, which relies upon critics perception of two critical attributes in wines: the higher/lower intensity of their aromas and avors (even if, as will be seen, intensity also plays a role in the assessment of wines texture or mouthfeel), and the longer/shorter durability or persistence of both features. Since intensity and persistence are relative, scalar variables, the verbs helping wine critics articulate them in TNs were located at different points of an intensity cline and a persistence cline respectively. In order to do so, I drew insights from the cognitive classications of manner-ofmotion verbs cited earlier, but adjusted them to the specic context of wine tasting. For whereas those classications focus on verbs mostly concerned with describing ways of moving, the verbs in the wine corpus attempt to articulate the intensity and persistence of wines nose and palate. Accordingly, my classication of verbs was done taking into account their role in the genre. That is, the classication is less detailed or unconcerned with illustrating the specics of motion as this happens in other contexts (e.g. the human realm). For instance, in the present discussion the semantic component of lower/higher energy corresponds to +/force, and rate and smooth motion have been subsumed by the more general notion of +/speed. This is shown in Fig. 1. Intensity is one of the critical dimensions in the assessment of wines aromas and avors (or a combination of both), and is also often used to assess the wine as a whole according to its olfactory and gustatory properties. The verbs in the intensity cline have been organized along two extremes according to the semantic notion of +/force. Thus, whenever wines aromas and/or avors are forceful or intensely perceived critics tend to use verbs placed in the furthermost positive extreme in the intensity cline such as burst, explode, erupt or power ones way. On the other hand, verbs such as glide or oat suggest that aromas and avors are not overpowering. The former situation is illustrated in examples (6) and (7), and the latter in passages (8) and (9): (6) Classy Chablis that stands as a monument to the 2000 vintage. So elegant and rened, powering its way across the palate with a reball of intensely concentrated lime, kiwi, pineapple, dried herbs, freshly cut grass and spices. This wine bursts from the glass with violets, lilies, blueberries, cherries, blackberries, and buttery oak. Bright and focused, offering delicious blueberry, plum and spice avors that glide smoothly through the silky nish. While the rst impression with Petrus is the wood, it is the fruit which gradually shows itself. It is extraordinary, this dense fruit, which simultaneously manages to oat with elegance.

(7) (8) (9)

6 Manner of motion has also been addressed by scholars from other schools of thought. Thus, whereas in Levin (1993) we nd motion verbs classied according to their semantics as well as their alternation patterns, in classical works such as Vendler (1967) and Dowty (1979) manner may be seen as subsumed by the lexical aspect or Aktionsart of verbs and is particularly related to the durativity and telicity features used in their verb classication. Since this paper starts from the basic assumptions in cognitive linguistics, the parameters considered mainly draw upon work in this tradition.

R. Caballero / Journal of Pragmatics 39 (2007) 20952114

2103

Fig. 1. Perceptibility/noticeability cline.

Nevertheless, although force whether positive or negative is a core notion in all the motion verbs in the corpus, other meanings are also present. Thus, +force combines with abruptness in leap, kick, pop or toss, as shown in passages (10)(12), and with +speed in swirl, race or zip, as shown in examples (13) and (14): (10) (11) (12) Wow. A smoky, nutty component leaps from the glass, backed by apricot and a beguiling spice and mineral element. [This wine] kicks off with the purest scent of smashed berries, and then offers up a supercharged black-cherry-laden palate. Yet once you think its aging potential might be short, the nish drives on for a long distance, tossing up coffee and earth notes.

2104

R. Caballero / Journal of Pragmatics 39 (2007) 20952114

(13) (14)

Bright and jazzy, a racy mouthful of raspberry, mineral, blackberry and game avors that swirl through the ne-textured nish. Distinctive, very monolithic, clean, pure and crisp, with fresh fruit zipping along the palate.

Positive force may also be combined with speed to convey that the wines aroma(s) and/ or avor(s) are discernable but not too strong or dominant. This is the case of expressions incorporating sneak, creep or claw ones way (the former two concerned with the notion of furtiveness, and somehow suggesting that the aromas/avors thus predicated are difcult to perceive). By way of illustration, consider the following extracts: (15) (16) (17) Exotic, exuding red berry aromas and avors of tropical fruit, spice and int that sneak up on you rather than hit you over the head. An austere style, showing more mineral and spice than fruit, though citrus and apple creep into the mix, ending on an almond note. This is a mineral-laden, acidic young wine. The fruit has barely begun clawing its way to the surface.

Finally, the furthermost extreme of the negative pole in the intensity scale is occupied by verbs such as segue, glide, bob, oat, unfurl or feel ones way. These combine force and speed, and suggest that the avors in a wine are subtle albeit noticeable (bob, feel ones way), form a continuum (segue, unfurl), or both things (glide, oat). The latter case is illustrated in extracts (8) and (9) seen earlier, whereas in (18) the verb is used to convey the subtlety of the wines avors, and in (19) the verb expresses that these form a continuum: (18) (19) [This wine] has rm, powerful dry fruit. It is still just feeling its way at this stage, a wine that can last 15/20 years at least. Creamy vanilla custard note segues into passion fruit and mineral tones in this balanced, racy kabinett.

The second dimension of perception is persistence, which also needs to be considered in scalar terms. Interestingly, it should be noted that, overall, the greater the force or intensity of wines aroma(s) and avor(s), the lesser their durability in the mouth and nose. Accordingly, those occupying the furthermost slot of the positive pole in the intensity cline schematized in Fig. 1 are often found in the furthermost slot of the negative pole in the durability cline and vice versa. The following examples illustrate how these verbs are used in TNs: (20) (21) [The wine] pours out beautifully focused pear, quince, honey and spice avors, yet manages to feel elegant and restrained as the avors sail on and on. Made in the so-called modern style, but with ne tannins and body. Some rm oak pops up late in the game, but if given a few years, that should be integrated.

Thus, whereas sail on and on (and, by the same token, extend, stretch, segue, fan out or run) suggests the persistence of the wines properties thus predicated (here, avors), pop and most verbs related to +force are usually concerned with the rst impression of the wines aroma(s) and avor(s), that is, with the notion of emergence/presence, and often imply the quick evanescence of the perceptual properties of the components at issue. Such verbs are often found

R. Caballero / Journal of Pragmatics 39 (2007) 20952114

2105

at the beginning of TNs in contrast to what happens with those in the positive end of the persistence cline which usually occur at the end of TNs. Indeed, irrespective of what motion verbs may mean in isolation, their role and, therefore, interpretation must be framed within the discourse context where they are used. The pragmatic genre constraints on critics choice of such verbs is addressed in the ensuing section. 4.2. The function of motion patterns in TNs Forced to assess and describe several thousand wines per year, usually in batches of similar wines, wine critics often resort to strategies of lexical variation so that their readers do not get bored with almost identical notes (see also Lehrer, 2006, in this respect). Nevertheless, although critics may write all these notes sequentially, their audiences do not necessarily read them in the same way. For instance, the growing number of online magazines and websites devoted to wine usually classify TNs according to wine type and region rather than date of evaluation. However, the consequences are very real: the desire for lexical variation sometimes translates into overuse of motion expressions. This is the case of patterns such as come across + adjective, run + adjective or the verb ride which, in many cases, could be replaced by neutral or copular verbs like be, there to be, appear, feel, taste, smell or, more accurately, by the expression can be discerned/perceived. The way they appear in the corpus is shown below: (22) (23) (24) (25) This estate wine is light and tastes a bit like white grapefruit. The palate runs heavy, and the nish tastes like a blend of grapefruit and celery. Ripe and focused, not a big wine but offering pure plum and blackberry avors that ride on a smooth texture. This is serious Pinot. It comes across deep and powerful in the mouth, suggesting plums, sweet blackberries and a hint of sun-warmed tomato. [A]t one moment its forward and seemingly modern. Then itll go all classic on you.

Overall, however, corpus data suggest that motion verbs play an important role in the description and assessment of wines. Moreover, critics choice of verb not only responds to the aforementioned shortage of lexical resources for the expression of smell and taste, but also appears to be determined by the idiosyncrasy of the wine tasting experience which, as has been noted, is recreated in the genre used to communicate it. Thus, many TNs start by describing the rst impression of the wine at issue in the tasters nose and in his/her palate the latter conventionally, and metonymically, referred to as the wines attack. Critics use of verbs combining +force plus abruptness (e.g. burst, explode, jump, kick off, pop, start off)7 at the beginning of their commentary is, in this regard, far from surprising. This is illustrated in examples (26)(30): (26) (27)

7

This sublime spicy, rened, powerful wine explodes in the mouth with a myriad of spices [. . .] This powerful [wine] jumps from the glass with mineral-infused pear aromas.

Some such verbs belong to the category appear verbs in Levin (1993). Moreover, as kindly noted by an anonymous referee, the use of verbs like kick off or burst may well illustrate the intertextual relationships between the TN and other genres in the media, particularly sports reviews. Thus, whereas kick off brings to mind football commentary, burst (from the gate) is typical of news concerned with horse-racing.

2106

R. Caballero / Journal of Pragmatics 39 (2007) 20952114

(28) (29) (30)

Medium-bodied, eshy, and rich, it pops onto the palate with waves of syrupy minerals, pears, and apples whose avors linger in its impressively long nish. A zippy Gruner that starts off with mineral and stone character, and nishes on a lemon note. Kicks off with a hint of citrus and butterscotch on the nose.

The vividness of these examples contrasts with the more neutral tone of descriptions relying upon verbs such as come off, come out or come across. Thus, although these verbs also include +force in their semantics, the intensity of the rst impression of the wine thus predicated is minimized the verbs merely denoting appearance/presence, and downplaying any other aspect involved. Moreover, whereas the verbs combining +force and abruptness are often used in positive assessment, come off/out/across appear to be more neutral, fullling a copular role (as pointed out earlier). This is shown in the following passages: (31) (32) This is a mutt of a white, an unexpected blend of Colombard, Riesling and Sauvignon that comes off like Gewurz at rst blush. Despite 14% alcohol, this Gewurz comes across as rather light in weight and deceptive.

Nevertheless, although positive assessment is mainly conveyed by means of verbs foregrounding the intensity of the wines olfactory and gustatory prole, the corpus also yields a few examples where a relative lack of force is what makes the wine at issue remarkable. A caveat is in order at this point. Wine assessment and, hence, the language used in this endeavor is relative rather than absolute: the description and evaluation of a given wine needs to be framed within the expectations raised by the wine region, type of grape, vintage, etc. In other words, what in a wine may be seen as a positive trait, in another may give rise to a negative critique. This is illustrated in passages (33) and (34) below, where the notions of furtiveness in creeps up sideways, and gentleness in bobs and weaves attempt to capture the subtleties in the olfactory and gustatory prole of the wines at issue, which make them stand out among others with a more forceful (or, to use a popular term in current TNs, in-your-face) character: (33) (34) Heres a wine that doesnt slap you silly, but creeps up sideways, with seductively soft tannins that carry subtle avors of blackberries and herbs. Full, classy and exciting from the rst sniff to the last essence of the nish. Along the way is a largely awless wine that bobs and weaves; at one moment its forward and seemingly modern. Then itll go all classic on you. Overall its a beauty with structure and style.

If a good attack is usually a bonus in positive assessment, quality wines are also praised for the persistence of their aromas and, above all, their avors (i.e. the wines length), as ascertained in the stage devoted to evaluating the wines aftertaste or nish. This is the last stage in any tasting procedure, and, therefore, the commentary thus concerned appears at the end of TNs. Among the verbs used to convey long persistence and, hence, positive evaluation we nd extend, expand, stretch, sail or branch out. This is shown below: (35) Sturdy, rich and detailed, with complex, earthy currant, sage, mineral, tobacco and anise avors that fan out and saturate the palate.

R. Caballero / Journal of Pragmatics 39 (2007) 20952114

2107

(36)

(37)

Dark, peppery and earthy overtones add substance to this chewy, remarkably complex red wine. It delivers a ripe core of plum and dried currant, then branches out, hinting at anise and mineral on the nish. Medium-bodied and very long on the nish, it just keeps riding into the sunset.

Another property of wines impinging upon critics positive or negative assessment is their texture or mouthfeel i.e. the tactile properties of the wine sensed inside the tasters mouth before swallowing, and resulting from the interaction of such components as sugar, glycerin, alcohol, tannins or acidity. Texture is positively assessed by means of guratively motivated adjectives such as velvety, smooth or silky; in turn, negative evaluation often relies upon adjectives such as rough, coarse, searing or sharp. Sometimes critics also use motion verbs to express the tactile impressions afforded by wines. Thus, when the focus is the smooth texture of the wine as a whole, verbs combining force and speed such as glide and unfold are the norm, as illustrated below: (38) (39) As big as it is, its a silky wine that glides across the palate. A velvety, expansive, eshy texture unfolds impressively on the palate to reveal beautiful fruit.

In turn, when a textural component stands among others, critics choice of verb appears to depend on the intensity with which that component is perceived. High intensity is articulated by means of verbs combining +force and +speed, as those in (40) and (41), or +force and abruptness, as shown in (42) and (43): (40) (41) (42) (43) Smooth, ripe and plush, an amazingly supple wine with a streak of ne acidity racing through the plum, spice and earth avors. Distinctive, very monolithic, clean, pure and crisp, with fresh fruit zipping along the palate. Full-bodied, the toasted oak kicks in on the lively, lingering, sweet-tasting, searingly intense nish. Tannins punch through on the nish, with a minty note, adding to this wines power.

On the other hand, when the wines textural components are less intense the tendency is to use verbs combining +force and speed: (44) (45) Firm in texture, with chewy tannins sneaking through on the nish. An austere style, showing more mineral and spice than fruit, though citrus and apple creep into the mix, ending on an almond note.

The examples seen so far also show that although certain motion verbs are used to describe the olfactory and gustatory prole of wines in the rst and nal stages of wine tasting (and, therefore, tend to occur either at the beginning or at the end of TNs), critics also use them to describe concrete aspects of the wine at issue, and insert them in the pertinent textual stretch. The choice of verb in these cases is largely determined by the wines property as this is perceived in the tasters nose and mouth irrespective of whether it is sensed in the initial, middle, or nal stage of the tasting procedure. A nal and related point worth considering is the fact that wine is an entity in constant evolution, not only during its period inside the cask or the bottle, but also during the very act of

2108

R. Caballero / Journal of Pragmatics 39 (2007) 20952114

tasting it: a wine may be one thing one minute after the bottle has been opened, and a very different one once it has sat or spent enough time in the glass (i.e. has breathed). As it is, some of the expressions used by critics evoke the different stages undergone by wines in the very process of drinking them. This is illustrated in the following passages: (46) (47) (48) (49) (50) Flavors of cranberries, black plums and dark cherries combine with layers of dry wood tannins into a wine that is still just emerging from its chrysalis. Explosive ripe, luscious fruit bursts from the glass in the pungent nose and expands full throttle on the palate. The wine unfolds and expands in the glass, offering lovely orange, mineral and tarragon avors. Vibrant and perfumed, with kirsch and raspberry avors that leap out of the glass and unfold in layers. Starts off very cedary, showing lots of toast and vanilla -also a hint of grilled meats. Explodes on the palate with bright red cherries, powering through chocolate notes onto the sweetly tannic nish.

Thus, whereas emerging from its chrysalis in passage (46) illustrates the use of a motion expression to articulate the developmental stage of the wine under focus (as also happened with claw/feel ones way in examples (17) and (18) seen earlier), examples (47)(50) show the use of motion patterns to describe the evolution of the wine (and the sensations provoked by this in the tasters) throughout the very tasting process. The foregoing description has attempted to demonstrate the weight of motion expressions in wine assessment. They have been seen as helping wine critics describe the organoleptic sensations concerned with smell, taste and mouth-feel in dynamic, rather than static terms. This construal of perception via nose and mouth is not solely constrained by the poverty of the lexical repository related to such experiences, but also appears to be congruent with the very dynamics of the tasting event: they both help critics articulate the various phases of a highly ordered sensory experience as well as describe the evolution of wines properties along the process. In turn, the high incidence of the expressions in the genre also gives credit to the cognitive linguistics postulate that we are biased towards dynamism (Langacker, 1986, 1987) as well as to Talmys (1996) notion of ception surveyed earlier in this paper (cf. section 2). In this regard, the motion patterns found in TNs would represent a highly idiosyncratic case of ctive motion whereby the evocation of particular ways of moving is used to communicate the smell, taste and touch experiences afforded by wine.8 Finally, apart from notions directly related to motion, some verbs in the corpus also carry entailments related to the attributes of the entities whose movement (volitional or otherwise) they typically help articulate outside the wine realm. In this sense, the verbs may be seen as slipping information from those domains of experience and entities in the predication of wines. The interest of these verbs, then, lies in the quality of the information thus added, and in the richer construal of wines effected through them. Indeed, some such motion cases point to conspicuous

8 Part of the idiosyncrasy of ctive motion expressions in wine discourse lies in the fact that most of them incorporate manner in their semantics contrary to what happens with the ctive motion expressions used in other contexts. Thus Matclock (2004) discusses two types of ctive motion patterns: a rst type which predicates entities (i.e. trajectors) associated with motion (e.g. a road) and may incorporate manner verbs, and a second type whose trajectors are not associated with motion (e.g. a cable) and, therefore, do not allow manner verbs.

R. Caballero / Journal of Pragmatics 39 (2007) 20952114

2109

metaphorical frames underlying winespeak, whose instantiations, of course, co-occur with motion-biased language in TNs. The gurative motivation of motion patterns in winespeak is the topic of the next section. 5. The gurative motivation of motion patterns in TNs The meaning potential of certain motion verbs in the corpus points to what Goatly (1997:8689) calls a vehicle construction process, that is, the multiple evocation of diverse metaphors by a single gurative expression. This is cued by incongruous colligation, and is especially related to metaphorically used verbs. He illustrates his point with the expression gills kneading quietly, where kneading evokes a typical action performed by hands and, thus, indirectly equates gills with these. Likewise, verbs such as jump, kick, run, dance, sneak, leap, swim, creep or punch in TNs may evoke an animate view of wines since they require agents whose bodies can move as also happens with the expressions claw/feel ones way in passages (17) and (18) cited earlier. By way of illustration, consider the following extracts: (51) (52) (53) The splash of acid [in this wine] keeps the avors on their toes (and dancing on your tongue) through a smooth, lingering nish. The blackcurrant, cassis, plum, mocha, smoky oak and spicy avors swim in wonderfully sweet, ne tannins. A spine of acidity keeps it all honest. Like a gymnast, this lithe white glides across the palate, its underlying strength and tautness merely supporting the dried apricot, guava, honey and candied citrus.

This view of wines is often reinforced by the verbs co-text, that is, by expressions alluding to other anatomical parts of the wines at issue (on their toes, spine), or by explicit comparisons of wines to human beings (like a gymnast). The fact that some such verbs further specify the limbs involved in the expressions reinforces an animal and/or human view of wines. This is the case of jump, kick, leap or run, which incorporate legs in their semantics. Passage (54) is very explicit in this respect9: (54) It strikes the right balance of weight and tang. Its a refreshing wine with the legs to run the race.

The use of such verbs is congruent with the large amount of personifying lexis in winespeak. Consider, for instance, such conventional descriptors in TNs as full-/medium-bodied, masculine, feminine, thin, fat, sinewy, shy or assertive (for a discussion on the current expansion of this anthropomorphic schema, see Lehrer, 2006). In turn, verbs like unfold, fold, extend, stretch and expand suggest a view of wines as MALLEABLE ENTITIES. Some of these verbs may also evoke a textile portrayal of wines, which is congruent with critics recurrent qualication of wines as being velvety, silky, loosely knit and supple, or as offering a tapestry of avors. This textile rendering is fully exploited in the following example: (55) This is a richly textured red wine that unfolds its ripe black cherry, blackberry and anise avors like a thick quilt. Soft, warm and generous, with a sweet, supple nish.

See also footnote 7.

2110

R. Caballero / Journal of Pragmatics 39 (2007) 20952114

Finally, the largest number of motion instances in the corpus involves verbs explode (102 occurrences) and burst (77 occurrences), which portray wines as if they were EXPLOSIVE ARTIFACTS. This construal is further reinforced by the frequent reference to wines as pleasure bombs or fruit bombs in TNs, and by critics use of related terms to describe the sensations provoked by wines in their nose and mouth (e.g. blast of aromas/avors, explosively aromatic wine, wine detonates on the palate). The following example illustrates this explosion frame: (56) A burst of avor. More intense than powerful, this vibrant white explodes with toast, almond and herb avors.

In sum, some manner-of-motion verbs in the corpus render wines as ANIMATE BEINGS (usually, human), MALLEABLE ENTITIES, and EXPLOSIVE ARTIFACTS, all of them conspicuous metaphors in winespeak. That is, the use of manner-of-motion verbs is congruent with some of the metaphorical schemas and lexis characterizing the wine realm. In turn, given the idiosyncrasy of wine tasting, motion expressions in general may be also seen as ultimately related to two other gurative phenomena: synesthesia and metonymy. The hypothesis that the expressions may be synesthetically motivated derives from the very nature of the experience they help verbalize (i.e. wine tasting), which is accessed via the basic senses of smell and taste, yet is communicated by means of lexis typical of another sense (albeit more complex or multiple since it involves other senses as well) such as motion.10 This attempt is inherently cross sensory, and this is precisely what synesthetic metaphors are about: metaphors that map across various sensory domains or modes (Day, 1996; Ramachandran and Hubbard, 2001; Yu, 2003). Moreover, although as animate beings we are able to perceive motion by moving ourselves, motion detection including, of course, the detection of the diverse variables impinging upon differences in manner of motion prior to their discrimination and storage in memory involves the sense of vision.11 If we keep in mind the kinesthetic and visual quality of translating smell and taste experiences into motion, the motion patterns in the corpus may well be seen as a specic case of synesthetic metaphor. However, if we consider the classication of motion verbs along the intensity and persistence clines in Fig. 1 the motion patterns in TNs may not only be synesthetically motivated, but also appear to be related to metonymy. This nds support if we bear in mind the emergent meanings conveyed by the verbs in the expressions. Thus, in the same way that nose and palate do not refer to any anatomical part of wine but to two stages in wine tasting, verbs such as kick off and sail on help critics express the intensity and duration of the wines aroma(s) and avor(s) as these are ascertained in the initial and nal stages of the tasting process (i.e. the wines attack and nish). For, of all aspects that may be involved in the actions denoted by motion verbs (the particulars of the location where the motion was effected, the agentive or non-agentive quality of the motion, etc.), these are only concerned with a few traits of the act of moving itself (+/force, abruptness, +/speed, or continuity of motion), mapping them onto sensory experience. In other words, the use a verb like pop in a TN does not concern the whole displacement denoted by

Motion is also known as a common sensible after Aristotles denition in De Anima. Interestingly, Morrot et al. (2001) discuss the interaction between the sense of vision (concretely, the vision of colors) and the discrimination of smells which, although unrelated to motion, also shows the cross-sensorial synesthetic quality of wine assessment.

11 10

R. Caballero / Journal of Pragmatics 39 (2007) 20952114

2111

the verb, but two of its salient properties or meanings, namely suddenness and force both also characterizing the wines organoleptic properties under focus. Put differently, the ctive motion cases found in wine commentary seem to rely on a metonymic selection of certain features from the semantics of the verbs involved in the expressions the whole displacements denoted by the verbs nevertheless standing for or providing the point of access to those traits. This is congruent with the view of metonymy as a construal of salience, that is, as evoking or highlighting particular aspects of a given entity, concept, or situation (Panther and Radden, 1999; Radden and Kovecses, 1999; Ruiz de Mendoza, 2000; Panther and Thornburg, 2003; Paradis, 2004). Likewise, together with compensating for the poverty of smell and taste terminology (both crucial aspects in wine assessment), manner-of-motion verbs in TNs help wine critics describe the most salient properties of the wine at issue in a highly economical way. In short, although motion expressions in TNs may be explained as specic instances of the phenomenon referred to as ctive motion, the verbs involved exemplify construal of salience and, accordingly, may be seen as related to metonymy. In turn, since the verbs are used to translate discrete sensory experiences into words via such a holistic and visually grounded experience as motion, they may also be seen as a case albeit highly specic or peculiar of synesthetic metaphor.12 6. Concluding remarks Motion expressions in TNs convey information about what wines smell and taste like in a dynamic rather than in a more conventional or literal static way, highlighting particular aspects of those sensory experiences. Indeed, as described in this paper, the idiosyncrasy of both smell and taste as well as the topic at issue (i.e. wine) may be seen as constraining the type of verb used in the expressions. The way they appear in the genre is also particularly interesting. Thus, whereas verbs conveying +force and abruptness are often found in the rst assessment of the wine at issue, those foregrounding duration or persistence are commonly used to convey its nal evaluation. In turn, motion verbs are also used to describe the various stages involved in wine tasting as well as the wines evolution throughout the very tasting process. In this sense, critics choice of verb responds both to the particular nature of wine tasting as well as to the rhetorical demands of the genre used to share this experience with the growing audience of wine lovers. Finally, although all the motion instances in the corpus illustrate a very particular case of ctive motion, some expressions have also been discussed as instantiating some of the metaphors underlying winespeak, namely WINES ARE ANIMATE BEINGS, MALLEABLE ENTITIES, and EXPLOSIVE ARTIFACTS. Given the particulars of the experience the expressions help to communicate, I have tentatively considered them as ultimately related to synesthetic metaphor and metonymy. This does not mean that wine critics are aware of the gurative quality of their commentary, or that the aforementioned metaphors are triggered or activated each time they use a motion expression in a TN. In this regard, the high incidence of motion expressions to describe the sensory experiences afforded by wines may also illustrate disciplinary acculturation through genre, that is, through discourse interaction (see the discussion in Chollet et al., 2005).

For a discussion on the relationship between synesthetic metaphor and metonymy, see Tsur (1987), and Barcelona (2000).

12

2112

R. Caballero / Journal of Pragmatics 39 (2007) 20952114

References

Amoraritei, Loredana, 2002. La metaphore en oenologie. Metaphorik.de 3, 112 Online document. Date of access: May 12th 2006. URL: [www.metaphorik.de/03/amoraritei.htm] Barcelona, Antonio, 2000. On the plausibility of claiming a metonymic motivation for conceptual metaphor. In: Barcelona, A. (Ed.), Metaphor and Metonymy at the Crossroads. Mouton de Gruyter, Berlin and New York, pp. 3158. Bernstein, Leonard S., 1998. The Ofcial Guide to Wine Snobbery. Quill, New York. Caballero, Rosario, 2006. Re-Viewing Space. Figurative Language in Architects Assessment of Built Space. Mouton de Gruyter, Berlin and New York. Caballero, Rosario. FORM IS MOTION. Dynamic predicates in English architectural discourse. In: Panther, Klaus-Uwe, Barcelona, Antonio, Thornburg, Linda (Eds.), Metonymy and Metaphor in Grammar, John Benjamins, Amsterdam and Philadelphia, forthcoming. Chollet, Sylvie, Valentin, Dominique, Abdi, Herve, 2005. Do trained assessors generalize their knowledge to new stimuli? Food Quality and Preference 16, 1323. Day, Sean, 1996. Synaesthesia and synaesthetic metaphors. Psyche 2 (32). Online document. Date of access: February 20th 2006. URL: [http://psyche.cs.monash.edu.au/v2/psyche-2-32-day.html]. Dowty, David, 1979. Word Meaning and Montague Grammar. Reidel, Dordrecht. Dowty, David, 1991. Thematic proto-roles and argument selection. Language 67, 547619. Eggins, Suzanne, 1994. An Introduction to Systemic Functional Linguistics. Pinter, London. Fillmore, Charles J., 1968. Lexical entries for verbs. Foundations of Language 4, 373393. Fillmore, Charles J., 1977. Topics in lexical semantics. In: Cole, Roger W. (Ed.), Current Issues in Linguistics Theory. Indiana University Press, Bloomington, pp. 76138. Gawel, Richard, 1997. The use of language by trained and untrained wine tasters. Journal of Sensory Studies 12, 267284. Gawel, Richard, Oberholster, Anita, 2001. A Mouth-feel Wheel: Terminology for Communicating the Mouth-feel Characteristics of Red Wine. Department of Horticulture, Viticulture and Oenology, University of Adelaide, Adelaide. Gibbs, Raymond W., 1994. The Poetics of Mind: Figurative Thought, Language and Understanding. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge and New York. Gluck, Malcolm, 2003. Wine language. Useful idiom or idiot-speak? In: Aitchison, Jean, Lewis, Diana M. (Eds.), New Media Language. Routledge, London, pp. 107115. Goatly, Andrew, 1997. The Language of Metaphors. Routledge, London and New York. Goldberg, Adele, 1998. Semantic principles of predication. In: Koenig, Jean-Pierre (Ed.), Discourse and Cognition: Bridging the Gap. CSLI Publications, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, pp. 4154. Gregutt, Paul, 2003. Scents and nonsense. The Seattle Times Pacic Northwest Magazine. Online document. Date of access: May 12th 2006. URL: [seattletimes.nwsource.com/pacicnw/2003/0112/taste.html]. Guerssel, Mohamed, Hale, Kenneth, Laughren, Mary, Levin, Beth, Eagle, Josie, 1985. A cross-linguistic study of transitivity alternations. In: Eilfort, William H., Kroeber, Paul D., Peterson, Karen L. (Eds.), Papers from the Parasession on Causatives and Agentivity, CLS 21(2), Chicago Linguistic Society, Chicago, IL, pp. 4863. Halliday, Michael A.K., 1985/1994. An Introduction to Functional Grammar. Edward Arnold, London. Hughson, Angus, Boakes, Robert, 2001. Perceptual and cognitive aspects of wine tasting expertise. Australian Journal of Psychology 53, 103108. Ibarretxe-Antunano, Iraide, 2004. Motion events in Basque narratives. In: Stromqvist, Sven, Verhoeven, Ludo (Eds.), Relating Events in Narrative: Typological and Contextual Perspectives. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Mahwah, NJ, pp. 89111. Ibarretxe-Antunano, Iraide, 2006. Sound Symbolism and Motion in Basque. LINCOM Studies in Basque Linguistics 06. Lincom, Munich. Jackendoff, Ray, 1990. Semantic Structures. The MIT Press, Cambridge, MA. Kaufmann, Ingrid, 1995. What is an (im-)possible verb? Restrictions on semantic form and their consequences for argument structure. Folia Linguistica 24, 67103. Kita, Sotaro, 1997. Two-dimensional semantic analysis of Japanese mimetics. Linguistics 35, 379415. Kita, Sotaro, 1999. Japanese enter/exit verbs without motion semantics. Studies in Language 23, 317340. Lakoff, George, 1993. The contemporary theory of metaphor. In: Ortony, Andrew (Ed.), Metaphor and Thought. second ed. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge and New York, pp. 202251. Lakoff, George, Johnson, Mark, 1980. Metaphors We Live by. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago and London.

R. Caballero / Journal of Pragmatics 39 (2007) 20952114

2113

Lakoff, George, Turner, Mark, 1989. More than Cool Reason: A Field Guide to Poetic Metaphor. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago and London. Langacker, Ronald, 1986. Abstract motion. In: Proceedings of the Twelfth Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society. Berkeley Linguistics Society, Berkeley, CA, [Reprinted in Langacker, Ronald, 1990. Concept, Image, and Symbol: The Cognitive Basis of Grammar. Mouton de Gruyter, Berlin], pp. 455471. Langacker, Ronald, 1987. Foundations of Cognitive Grammar, vol. I, Theoretical Prerequisites. Stanford University Press, Stanford, CA. Lawless, Harry, 1984. Flavour description of white wine by expert and non-expert wine consumers. Journal of Food Science 49, 120123. Lehrer, Adrienne, 1974. Semantic Structure and Lexical Fields. North-Holland, Amsterdam. Lehrer, Adrienne, 1983. Wine and Conversation. Indiana University Press. Lehrer, Adrienne, 1992. Wine vocabulary and wine description. Verbatim: The Language Quarterly 18 (3), 1315. Lehrer, Adrienne, 2006. Wine and Conversation: A new look. In: Andor, Jozsef, Pelyvas, Peter (Eds.), Empirical, Cognitive-based Studies in the Semantics-Pragmatics Interface, CRISPI, Elsevier Science, Oxford. Levin, Beth, 1993. English Verb Classes and its Alternations. University of Chicago Press, Chicago. Levin, Beth, Rappaport Hovav, Malka, 1992. The lexical semantics of verbs of motion: the perspective from unaccusativity. In: Roca, Iggy (Ed.), Thematic Structure: Its Role in Grammar. Foris, Berlin, pp. 247269. Malblanc, Alfred, 1968. Stylistique Comparee du Francais et de lAllemand. Didier, Paris. Martin, James R., Matthiessen, Christian, Painter, Clare, 1997. Working with Functional Grammar. Arnold, London and New York. Matclock, Teenie, 2004. The conceptual motivation of ctive motion. In: Radden, Gunter, Panther, Klaus-Uwe (Eds.), Studies in Linguistic Motivation. Mouton de Gruyter, Berlin and New York, pp. 221248. Matsumoto, Yo, 1996. Subjective motion in English and Japanese verbs. Cognitive Linguistics 7, 183226. Moore, Victoria, 1999. The word on wine: wine description. New Statesman 3, May. Mora Gutierrez, Juan Pablo, 2001. Directed Motion in English and Spanish. Estudios de Lingustica Espanola 11. Online document. Date of access: 7th January 2005. URL: [elies.rediris.es/elies11]. Morimoto, Yuko, 2001. Los Verbos de Movimiento. Visor, Madrid. Morrot, Gil, Brochet, Frederic, Dubourdieu, Denis, 2001. The color of odors. Brain and Language 79 (2), 309320. Nedlinko, Anatoli, 2006. Viticulture and winemaking terminology and terminography. Terminology 12 (1), 137164. Noble, Ann, Arnold, Richard, Buechsenstein, John, Leach, Jane, Schmidt, Janice, Stern, Peter, 1987. Modication of a standardised system of wine aroma terminology. American Journal of Oenology and Viticulture 38 (2), 143146. Ozcaliskan, S eyda, 2004. Typological variation in encoding the manner, path, and ground components of a metaphorical motion event. Annual Review of Cognitive Linguistics 2, 73102. Panther, Klaus-Uwe, Radden, Gunter (Eds.), 1999. Metonymy in Language and Thought. John Benjamins, Amsterdam and Philadelphia. Panther, Klaus-Uwe, Thornburg, Linda (Eds.), 2003. Pragmatic Inferencing in Metonymy. John Benjamins, Amsterdam and Philadelphia. Paradis, Carita, 2004. Where does metonymy stop? Senses, facets, and active zones. Metaphor and Symbol 19 (4), 245264. Peynaud, Emile, 1987. The Taste of Wine. Macdonald Orbis, London. Pierre, Brian, 1998. War of the words. Food and Wine Magazine, May. Radden, Gunter, Kovecses, Zoltan, 1999. Towards a theory of metonymy. In: Panther, Klaus-Uwe, Radden, Gunter (Eds.), Metonymy in Language and Thought. John Benjamins, Amsterdam and Philadelphia, pp. 1759. Ramachandran, Vilayanur, Hubbard, Edward, 2001. SynaesthesiaA window into perception, thought and language. Journal of Consciousness Studies 8 (12), 334. Rappaport Hovav, Malka, Levin, Beth, 1998. Building verb meanings. In: Butt, Miriam, Geuder, Wilhelm (Eds.), The Projection of Arguments: Lexical Compositional Factors. Center for the Study of Language and Information, Stanford, CA, pp. 97134. Ruiz de Mendoza, Francisco, 2000. The role of mappings and domains in understanding metonymy. In: Barcelona, Antonio (Ed.), Metaphor and Metonymy at the Crossroads. Mouton de Gruyter, Berlin and New York, pp. 109132. Silverstein, Michael, 2004. Cultural concepts and the language-culture nexus. Current Anthropology 45 (5), 621652. Slobin, Dan, 1996. Two ways to travel: verbs of motion in English and Spanish. In: Shibatani, Masayoshi, Thompson, Sandra (Eds.), Grammatical Constructions: Their Form and Meaning. Clarendon Press, Oxford, pp. 195219. Slobin, Dan, 2000. Verbalized events: a dynamic approach to linguistic relativity and determinism. In: Niemeier, Susan, Dirven, Rene (Eds.), Evidence for Linguistic Relativity. Mouton de Gruyter, Berlin, pp. 107138.

2114

R. Caballero / Journal of Pragmatics 39 (2007) 20952114

Slobin, Dan, 2004. The many ways to search for a frog: linguistic typology and the expression of motion events. In: Stromqvist, Sven, Verhoeven, Ludo (Eds.), Relating Events in Narrative: Typological and Contextual Perspectives. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Mahwah, NJ, pp. 219257. Solomon, Gregg, 1990. Psychology of novice and expert wine talk. American Journal of Psychology 105, 495517. Solomon, Gregg, 1997. Conceptual change and wine expertise. The Journal of the Learning Sciences 6, 4160. Talmy, Leonard, 1983. How language structures space. In: Pick, Herbert, Acredolo, Linda (Eds.), Spatial Orientation: Theory, Research and Application. Plenum Press, New York, pp. 225282. Talmy, Leonard, 1985. Lexicalization patterns: semantic structure in lexical forms. In: Shopen, Timothy (Ed.), Language Typology and Syntactic Description. Grammatical Categories and the Lexicon, vol. III. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp. 57149. Talmy, Leonard, 1988. Force dynamics in language and thought. Cognitive Science 12, 49100. Talmy, Leonard, 1991. Path to realization: a typology of event conation. In: Proceedings of the Seventeenth Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society. Berkeley Linguistics Society, Berkeley, pp. 480519. Talmy, Leonard, 1996. Fictive motion in language and ception. In: Bloom, Paul, Peterson, Mary, Nadel, Lynn, Garrett, Merrill (Eds.), Language and Space. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA and London, pp. 211276. Talmy, Leonard, 2000. Toward a Cognitive Semantics, vol. I, Conceptual Structuring Systems. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA. Tenny, Carol, 1994. Aspectual Roles and the Syntax-Semantics Interface. Kluwer, Dordrecht. ` Tesniere, Lucien, 1957/1994. Elementos de Sintaxis Estructural. Gredos, Madrid. Thompson, Geoff, 1996. Introducing Functional Grammar. Arnold, London and New York. Tsur, Reuven, 1987. On Metaphoring. Israel Science Publishers, Jerusalem. Van Valin, Robert D.J., 1990. Semantic parameters of split intransitivity. Language 66, 221260. Vendler, Zeno, 1967. Linguistics in Philosophy. Cornell University Press, Ithaca. Vinay, Jean-Paul, Darbelnet, Jean, 1958. Stylistique Comparee du Francais et de lAnglais. Didier, Paris. Wandruszka, Mario, 1976. Nuestros Idiomas, Comparables e Incomparables. Gredos, Madrid. Yu, Ning, 2003. Synesthetic metaphor: a cognitive perspective. Journal of Literary Semantics 32, 1934.

Further reading

Aristotle, 1976. De Anima (Hicks, Robert, Trans.). Arno, New York. Rosario Caballero is a lecturer of English and linguistics in the Department of Modern Languages of University of Castilla-La Mancha (Spain). Her research interests pivot on metaphor research in discourse contexts. Some of her publications are the following: 2003a. Metaphor and genre: The presence and role of metaphor in the building review. Applied Linguistics 24 (2). 2003b. Talking about space: image metaphor in architectural discourse. Annual Review of Cognitive Linguistics 1. 2006. Re-Viewing Space. Figurative Language in Architects Assessment of Built Space. Berlin and New York, Mouton de Gruyter. Forthcoming. FORM IS MOTION. Dynamic predicates in English architectural discourse. In: Panther, Klaus-Uwe, Barcelona, Antonio, Thornburg, Linda (Eds.), Metonymy and Metaphor in Grammar. Amsterdam and Philadelphia, John Benjamins.

You might also like

- Advanced English Grammar with ExercisesFrom EverandAdvanced English Grammar with ExercisesRating: 2.5 out of 5 stars2.5/5 (12)

- Laundry Stain Remover ChartDocument1 pageLaundry Stain Remover ChartEva TuáNo ratings yet

- Utility Pump Station Design SpreadsheetDocument16 pagesUtility Pump Station Design SpreadsheetFarhat Khan100% (4)

- Equivalence in Translation Theories A Critical EvaluationDocument6 pagesEquivalence in Translation Theories A Critical EvaluationClaudia Rivas Barahona100% (1)

- Rice PostharvestDocument39 pagesRice PostharvestOliver TalipNo ratings yet

- Euripides I: Alcestis, Medea, The Children of Heracles, HippolytusFrom EverandEuripides I: Alcestis, Medea, The Children of Heracles, HippolytusNo ratings yet

- Carrying CapacitiesDocument10 pagesCarrying Capacitiesapi-218357020100% (1)

- Linguistic modality in Shakespeare Troilus and Cressida: A casa studyFrom EverandLinguistic modality in Shakespeare Troilus and Cressida: A casa studyNo ratings yet

- The Integrated Approach of Yoga Therapy For Good LifeDocument9 pagesThe Integrated Approach of Yoga Therapy For Good LifeChandra BalaNo ratings yet

- Slobin-1996-Two Ways To TravelDocument13 pagesSlobin-1996-Two Ways To TravelMili OrdenNo ratings yet

- Cognitive Linguistics Issue1 4.vol.19Document594 pagesCognitive Linguistics Issue1 4.vol.19wwalczynskiNo ratings yet

- 2016 The Semantics of Spatial PrepositionsDocument25 pages2016 The Semantics of Spatial PrepositionsKrishna-lila Devi DasiNo ratings yet

- Silverstein - Metapragmatic Discourse and Metapragmatic FunctionDocument15 pagesSilverstein - Metapragmatic Discourse and Metapragmatic Functionadamzero100% (3)

- Tiffin ServiceDocument8 pagesTiffin ServiceAbhishek Soni100% (1)

- Monogragie 2Document31 pagesMonogragie 2Angela Cojocaru-MartaniucNo ratings yet

- Cifuentes Paula - Semantics English SpanishDocument40 pagesCifuentes Paula - Semantics English SpanishbunburydeluxNo ratings yet

- The Conceptual Motivation of Fictive Motion: Teenie MatlockDocument28 pagesThe Conceptual Motivation of Fictive Motion: Teenie MatlockaaaolaNo ratings yet

- Communication Verbs in Chinese and English: A Contrastive AnalysisDocument27 pagesCommunication Verbs in Chinese and English: A Contrastive AnalysisNgọc Trân PhanNo ratings yet

- Kobe University Repository: KernelDocument16 pagesKobe University Repository: KernelGoranNo ratings yet

- Andersen 1990 The Structure of Drift Papers From The 8th ICHLDocument20 pagesAndersen 1990 The Structure of Drift Papers From The 8th ICHLIker SalaberriNo ratings yet

- 1992 Topological PathsDocument8 pages1992 Topological PathsCandy Milagros Angulo PandoNo ratings yet

- Chen Guo 2009Document18 pagesChen Guo 2009dongliang xuNo ratings yet

- Jezikoslovlje 1 04-1-011 BarcelonaDocument31 pagesJezikoslovlje 1 04-1-011 Barcelonagoran trajkovskiNo ratings yet

- Translation Proper Names in Children's LiteratureDocument10 pagesTranslation Proper Names in Children's LiteraturePaulina Kaleta100% (1)

- (2008) Slobin - Paths of Motion & VisionDocument22 pages(2008) Slobin - Paths of Motion & VisionThana AsyloNo ratings yet

- ASL Viewponts Janzen 0510Document31 pagesASL Viewponts Janzen 0510אדמטהאוצ'והNo ratings yet

- University of Illinois Press Society For EthnomusicologyDocument3 pagesUniversity of Illinois Press Society For EthnomusicologysopranopatriciaNo ratings yet

- Silva-Corvalan 1983Document22 pagesSilva-Corvalan 1983Pablo ZdrojewskiNo ratings yet

- 2002 Linguistic Typology in Motion EventDocument39 pages2002 Linguistic Typology in Motion EventMohammed HachimiNo ratings yet

- What Translation Tells Us About Motion: A Contrastive Study of Typologically Different LanguagesDocument26 pagesWhat Translation Tells Us About Motion: A Contrastive Study of Typologically Different LanguagesHelio Parente De Vasconcelos Neto UFCNo ratings yet

- Matlock Bergmann 2015 Fictive MotionDocument17 pagesMatlock Bergmann 2015 Fictive MotionOlesea BodeanNo ratings yet

- BookDocument20 pagesBookOlesea BodeanNo ratings yet

- GrammarDocument28 pagesGrammarmarcelolimaguerraNo ratings yet

- D F M I D: Epicting Ictive Otion N RawingsDocument18 pagesD F M I D: Epicting Ictive Otion N RawingsDiana MovsisyanNo ratings yet

- Spontaneous and Non-Spontaneous Turn-Taking: 1. Taking Turns When TalkingDocument32 pagesSpontaneous and Non-Spontaneous Turn-Taking: 1. Taking Turns When TalkingTalmid Yosef Ben YosefNo ratings yet

- Tense Aspect in Verbal MorphologyDocument16 pagesTense Aspect in Verbal MorphologyErdélyi CsillaNo ratings yet

- Arabic Metaphor in Day To Day Speech PDFDocument20 pagesArabic Metaphor in Day To Day Speech PDFمصطفى بن ستيفن نيكولاسNo ratings yet

- L-Grammatical (Morphological) Aspects of StylisticsDocument5 pagesL-Grammatical (Morphological) Aspects of StylisticsZirnykRuslanaNo ratings yet

- Semantics and PragmaticsDocument38 pagesSemantics and PragmaticsLuka SmiljanicNo ratings yet

- 09 Structural Patterns IiDocument16 pages09 Structural Patterns IiNieves RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Toward Multimodal EthnopoeticsDocument33 pagesToward Multimodal EthnopoeticspalinurodimessicoNo ratings yet

- Venuti 2021 SaturnusDocument24 pagesVenuti 2021 SaturnusAndrea PizzottiNo ratings yet

- 2005 Gianollo Middle LatinDocument14 pages2005 Gianollo Middle LatinjmfontanaNo ratings yet

- Lehmann - Problems of Proto-Indo-European Grammar - Residues From Pre-Indo-European Active Structure (1989)Document10 pagesLehmann - Problems of Proto-Indo-European Grammar - Residues From Pre-Indo-European Active Structure (1989)Allan BomhardNo ratings yet

- Bentein - Verbal Periphrasis in Ancient GreekDocument49 pagesBentein - Verbal Periphrasis in Ancient GreekDmitry Dundua100% (1)

- Thinking For Translating and Intra-Typological Variation in Satellite-Framed LanguagesDocument25 pagesThinking For Translating and Intra-Typological Variation in Satellite-Framed Languageskylithon35No ratings yet

- Discourses in Place Language in The MateDocument5 pagesDiscourses in Place Language in The Mateanon_782600150No ratings yet

- Acuna Farina 2009 CloseappositionDocument30 pagesAcuna Farina 2009 Closeappositionthein ZAwNo ratings yet

- Supalla 2003 Classifier PredicatesDocument9 pagesSupalla 2003 Classifier PredicatesnoeliaNo ratings yet

- Stylistics: January 2011Document11 pagesStylistics: January 2011Shaimaa AbdallahNo ratings yet

- What Translation Tells Us About MotionDocument26 pagesWhat Translation Tells Us About MotionRegi TralariNo ratings yet

- 2 Silverstein EnregistermentDocument31 pages2 Silverstein EnregistermentDaniel SilvaNo ratings yet

- Dialectology and Language ChangeDocument4 pagesDialectology and Language ChangemiftaNo ratings yet

- Language Is A Complex and Multifaceted Phenomenon That Varies Over Time and Between CulturesDocument5 pagesLanguage Is A Complex and Multifaceted Phenomenon That Varies Over Time and Between CulturesEgle DubosNo ratings yet

- Linguistic v8 Stephanie PourcelDocument14 pagesLinguistic v8 Stephanie PourcelSergio BrodskyNo ratings yet

- Introduction Global Landscapes of TranslationDocument16 pagesIntroduction Global Landscapes of Translation高瑞梓No ratings yet

- AWEJ For Translation & Literacy Studies Volume, 1 Number 3, AugustDocument23 pagesAWEJ For Translation & Literacy Studies Volume, 1 Number 3, AugustAsim KhanNo ratings yet

- AWEJ For Translation & Literacy Studies Volume, 1 Number 3, AugustDocument23 pagesAWEJ For Translation & Literacy Studies Volume, 1 Number 3, AugustAsim KhanNo ratings yet

- Constructions With Subject vs. Object Experiencers in Spanish and ItalianDocument38 pagesConstructions With Subject vs. Object Experiencers in Spanish and Italianvvr1960No ratings yet

- Multimodal CorpusDocument28 pagesMultimodal CorpusAlan Emmanuel PerezNo ratings yet

- Bright - With One Lip - 1990Document17 pagesBright - With One Lip - 1990Juan Carlos Torres LópezNo ratings yet

- Chapter 5 (Language Variation) .Imam Hidayatullah Al Qadrie.f1022131066Document3 pagesChapter 5 (Language Variation) .Imam Hidayatullah Al Qadrie.f1022131066Villa RiaNo ratings yet

- Turn Taking PhrasesDocument32 pagesTurn Taking Phrasessnowdrop3010No ratings yet

- Smith, C. Discourse ModesDocument24 pagesSmith, C. Discourse ModesshamyNo ratings yet

- Handbook of Cognitive Linguistics POLYSEDocument50 pagesHandbook of Cognitive Linguistics POLYSEreinlikemNo ratings yet

- Spray Drying Technique of Fruit Juice Powder: Some Factors Influencing The Properties of ProductDocument10 pagesSpray Drying Technique of Fruit Juice Powder: Some Factors Influencing The Properties of ProductNanda AngLianaa KambaNo ratings yet

- Primerok Prasanja Jahja KemalDocument2 pagesPrimerok Prasanja Jahja KemalBeti Murdzoska-Taneska0% (1)

- Instrumen Saringan Membaca Tahun 3Document13 pagesInstrumen Saringan Membaca Tahun 3cikgudillaNo ratings yet

- Corporate Image enDocument8 pagesCorporate Image enDanfert PinedoNo ratings yet

- Perspectives in PharmacyDocument7 pagesPerspectives in Pharmacygizelle mae pasiolNo ratings yet

- Nelson/Salmo Pennywise Nov. 8, 2016Document40 pagesNelson/Salmo Pennywise Nov. 8, 2016Pennywise PublishingNo ratings yet

- Overall Marketing Activities of AFBLDocument30 pagesOverall Marketing Activities of AFBLNafis Hasan ShamitNo ratings yet

- Bread and Pastry Production Ncii Grade 11 Assessment Week1-2Document2 pagesBread and Pastry Production Ncii Grade 11 Assessment Week1-2Rio Krystal Reluya MolateNo ratings yet

- Amul Ice CreamDocument18 pagesAmul Ice CreamIshu BhaliaNo ratings yet

- Containers and Amounts PDFDocument2 pagesContainers and Amounts PDFHERNAN JAVIER MOHENO PEREZNo ratings yet