Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Crim2 Digests

Uploaded by

Amin JulkipliOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Crim2 Digests

Uploaded by

Amin JulkipliCopyright:

Available Formats

People v.

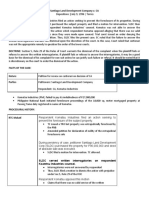

Castillo, 325 SCRA 613 Facts: At the construction site of Gaisano Building in Lapaz, Iloilo City, a construction worker, ROBERTO LUSTICA, was on the stairs of the third floor of the building when he saw his co-worker ROGELIO ABAWAG being pursued by the accused JULIAN CASTIILLO, a lead man in the same construction site. At the end of the chase, LUSTICA saw CASTILLO point a gun at ABAWAG and shot him. ABAWAG was about a half meter away from CASTILLO when the former fell on his knees beside a pile of hollow blocks FRANKLIN ACASO, a mason working on the Gaisano building, corroborated LUSTICAs testimony. ACASO said he heard the first shot and second shot as well as and a person screaming: "Ouch, that is enough!" When he looked towards the direction of the sound, he saw CASTILLO in front of ABAWAG pointing a .38 caliber revolver at the latter. ACASO testified that ABAWAG was then leaning on a pile of hollow blocks, pleading for mercy when CASTILLO shot Abawag. CASTILLO then fled, leaving Abawag lifeless The management of Gaisano reported the shooting incident to the police. JUN LIM, brother-in-law of ABAWAG and also a construction worker at the site, volunteered to go with the police to assist them in locating the accused CASTILLo. They proceeded to Port of San Pedro where they saw CASTILLO on board a vessel bound for Cebu. LIM positively identified CASTILLO as the assailant. CASTILLO attempted to escape but the police caught up with him. The police found in CASTILLOs possession a .38 caliber handmade revolver, three (3) empty shells and (3) live ammunitions. Inquiry revealed that CASTILLO owned the gun but had no license to possess it. The police then took CASTILLO into custody and charged him for the murder of Abawag and for illegal possession of firearm At the trial, CASTILLO interposed self-defense as his defense BUT the trial court did not give it credence. CASTILLO was convicted of Homicide (as the prosecution failed to prove the qualifying circumstances of evident premeditation and treachery) and sentenced him to suffer the penalty of imprisonment of prision mayor, as minimum, to reclusion temporal, as maximum; Separately, CASTILLO was also convicted of Illegal Possession of Firearm, aggravated by homicide, to which he was sentenced with the penalty of DEATH. On automatic review to the Supreme Court, CASTILLO impugns solely his conviction for illegal possession of firearm for which he was sentenced to the supreme penalty of death. ISSUE:

WON the RTC correctly convicted CASTILLO for the separate crime of illegal possession of firearms aggravated by homicide HELD: NO. It was an error for the trial court to convict CASTILLO of two separate offenses, i.e., Homicide and Illegal Possession of Firearms, and punish him separately for each crime. RATIO: With the passage of Republic Act No. 8294 (RA 8294) on June 6, 1997, the use of an unlicensed firearm in murder or homicide is now considered, not as a separate crime, but merely a special aggravating circumstance. This amendment has two (2) implications: first, the use of an unlicensed firearm in the commission of homicide or murder shall not be treated as a separate offense, but merely as a special aggravating circumstance; second, as only a single crime (homicide or murder with the aggravating circumstance of illegal possession of firearm) is committed under the law, only one penalty shall be imposed on the accused.8 Considering that these provisions of the amendatory law are favorable to CASTILLO, the new law should be retroactively applied Based on the facts of the case, the crime for which CASTILLO may be charged is homicide, aggravated by illegal possession of firearm, the correct denomination for the crime, and not illegal possession of firearm, aggravated by homicide. It is the possession of unlicensed firearm which aggravates the crime of homicide under RA 8294. CASTILLOs further assertion that his conviction was unwarranted since no proof was adduced by the prosecution that he was not licensed to possess the subject firearm is also MERITORIOUS. Two (2) requisites are necessary to establish illegal possession of firearms: first, the existence of the subject firearm, and second, the fact that the accused who owned or possessed the gun did not have the corresponding license or permit to carry it outside his residence. The onus probandi of establishing these elements as alleged in the Information lies with the prosecution. The first element the existence of the firearm was indubitably established by the prosecution. The prosecutions eyewitness ACASO saw CASTILLO shoot the victim thrice with a .38 caliber revolver. CASTILLO himself admitted the existence of the gun. The same gun was recovered from CASTILLO and offered in evidence by the prosecution.

However, no proof was adduced by the prosecution to establish the second element of the crime, i.e., that CASTILLO was not licensed to possess the firearm. This negative fact constitutes an essential element of the crime as mere possession, by itself, is not an offense. The lack of a license or permit should have been proved either by the testimony or certification of a representative of the PNP Firearms and Explosives Unit that the accused was not a licensee of the subject firearm or that the type of firearm involved can be lawfully possessed only by certain military personnel. As the Information alleged that CASTILLO possessed an unlicensed gun, the prosecution is duty-bound to prove this allegation. It is the prosecution who has the burden of establishing beyond reasonable doubt all the elements of the crime charged, consistent with the basic principle that an accused is presumed innocent until proven guilty. Thus, if the non-existence of some fact is a constituent element of the crime, the onus is upon the State to prove this negative allegation of nonexistence. IN THE CASE AT BAR, although CASTILLO himself admitted that he had no license for the gun recovered from his possession, his admission will not relieve the prosecution of its duty to establish beyond reasonable doubt the lack of license or permit to possess the gun. By its very nature, an "admission is the mere acknowledgment of a fact or of circumstances from which guilt may be inferred, tending to incriminate the speaker, but not sufficient of itself to establish his guilt. An admission in criminal cases is insufficient to prove beyond doubt the commission of the crime charged. Moreover, said admission is extrajudicial in nature. As such, it does not fall under Section 4 of Rule 129 of the Revised Rules of Court which states: An admission, verbal or written, made by a party in the course of the trial or other proceedings in the same case does not require proof. Not being a judicial admission, said statement by CASTILLO does not prove beyond reasonable doubt the second element of illegal possession of firearm. It does not even establish a prima facie case. It merely bolsters the case for the prosecution but does not stand as proof of the fact of absence or lack of a license. Additionally, the extrajudicial admission was made without the benefit of counsel. Thus, we hold that the appellant may only be held liable for the crime of simple homicide under Article 249 of the Revised Penal Code. He is sentenced to imprisonment of from nine (9) years and four (4) months of prision mayor as minimum to sixteen (16) years, five (5) months and nine (9) days of reclusion temporal as maximum.

ADVINCULA v. CA, 343 SCRA 134 At around 3:00 PM, private respondent Isagani ISAGANI OCAMPO was on his way home when petitioner Noel ADVINCULA and two (2) of his drinking companions started shouting invectives at him and challenging him to a fight. ADVINCULA, armed with a bolo, ran after ISAGANI who was able to reach home and elude his attackers. When AMANDO OCAMPO, father of ISAGANI, learned that ADVINCULA had chased ISAGANI with a bolo, AMANDO got his .22 caliber gun, which he claimed was licensed, and confronted ADVINCULA who continued drinking with his friends. But ADVINCULA threatened to attack AMANDI with his bolo, thus prompting the latter to aim his gun upwards and fire a warning shot. Cooler heads intervened and AMANDO was pacified and left. Later, however, he saw ADVINCULA's drinking companions firing at ADVINCULA's house. According to ADVINCULAs version, he and his friends were having a conversation outside his house when ISAGANI passed by and shouted at them. This led to a heated argument between him and ISAGANI. After ISAGANI left, he returned forthwith his father AMANDO and brother JERRY. The OCAMPOs were each armed with a gun which started ADVINCULA to run home to avoid harm but that respondents OCAMPOs continued shooting, hitting ADVINCULA's residence in the process. The controversy in this petition arose from the complaint filed by ADVINCULA for Illegal Possession of Firearms against the OCAMPOs. ADVINCULA's complaint was supported by a certification of the Firearms and Explosives Unit of the Philippine National Police stating that the OCAMPOs had no records in that office. The Assistant Provincial Prosecutor, with the approval of the Provincial Prosecutor, however dismissed ADVINCULA's complaint for lack of evidence. The Prosecutor found that the firearm in question is in fact covered by a firearm license duly issued by the chief of the Firearm and Explosives Office. ADVINCULA filed a petition for review with the Secretary of Justice insisting that the pieces of evidence he presented before the Provincial Prosecutor were sufficient to make a prima facie case for Illegal Possession against the OCAMPOs and prayed that the dismissal of his complaint be set aside. In his Resolution, the Secretary of Justice granted ADVINCULA's appeal and ordered the Provincial Prosecutor of Cavite to file the corresponding charges of Illegal Possession of Firearms against the OCAMPOs. The SOJ held that while the questioned firearm was duly licensed, no evidence was submitted to prove that he is possessed of the necessary permit to carry the firearm outside of his residence. In other words, his possession of the firearm, while valid at first, became illegal the moment he carried it out of his place of abode. Pursuant to the Resolution of the SOJ, the Provincial Prosecutor of Cavite filed the Informations against Amando and Isagani Ocampo for Illegal Possession of Firearms before the Regional Trial Court of Bacoor, Cavite. The OCAMPOs filed a

Petition for Certiorari and Prohibition under Rule 65 with the Court of Appeals questioning the Resolution of the Secretary of Justice. The Court of Appeals agreed with the OCAMPOs and ordered the SOJs resolution reversed and set aside. The CA held that there is no probable cause to hail the OCAMPOs for trial for illegal possession of firearms. Hence, this petition. ISSUE: WON the Court of Appeals erred in setting aside the Resolution of the Secretary of Justice. In other words, was there sufficient evidence to warrant the filing of charges for Illegal Possession of Firearms against the OCAMPOs? HELD: YES, the CA erred. The Secretary of Justice did not commit grave abuse of discretion in directing the filing of criminal Informations against private respondents, and clearly, it was error for the Court of Appeals to grant certiorari against the SOJ. RATIO: The rule is well settled that in cases of Illegal Possession of Firearms, two (2) things must be shown to exist: (a) the existence of the firearm, and (b) the fact that it is not licensed. However, it should be noted that even if he has the license, he cannot carry the firearm outside his residence without legal authority therefor." This ruling is a reiteration of the last paragraph of Sec. 1 of PD 1866, to wit: The penalty of prision mayor shall be imposed upon any person who shall carry any licensed firearm outside his residence without legal authority therefor. FURTHERMORE, this petition arose from a case which was still in its preliminary stages, the issue being whether there was probable cause to hold the OCAMPOs for trial. Probable cause, for purposes of filing criminal information, has been defined as such facts as are sufficient to engender a well-founded belief that a crime has been committed and that respondent is probably guilty thereof. The determination of its existence lies within the discretion of the prosecuting officers after conducting a preliminary investigation upon complaint of an offended party Their decisions, however, are reviewable by the Secretary of Justice who may direct the filing of the corresponding information or to move for the dismissal of the case. This procedure is in no wise in the nature of a trial that will finally adjudicate the guilt or innocence of the accused. The requisite evidence for convicting a person of the crime of Illegal Possession of Firearms is not needed at this point. It is enough that the Secretary of Justice found that the facts would constitute a violation of PD 1866. The Court of Appeals also took note of the fact that ADVINCULA's appeal to the Secretary of Justice was filed out of time. Per DOJ Circular No. 7, the aggrieved party has fifteen (15) days to appeal resolutions of the Provincial Prosecutor dismissing a criminal complaint. IN THIS CASE, ADVINCULA filed his appeal four (4)

months after receiving the Provincial Prosecutor's decision dismissing his complaint. This notwithstanding, the Secretary of Justice gave due course to the appeal. FINALLY, the filing of the Petition for Certiorari with the Court of Appeals against the SOJ was not the proper remedy. When the OCAMPOs petition was filed with the CA, the Information was already filed by the Provincial Prosecutor with the Regional Trial Court of Bacoor, Cavite. The criminal case commenced from that time and its course from that point was under the direction of the trial court. The preliminary investigation conducted by the fiscal for the purpose of determining whether a prima facie exists warranting the prosecution of the accused is terminated upon the filing of the information in the proper court. The filing of said information sets in motion the criminal action against the accused in Court. Once the case had already been brought to court, whatever disposition the fiscal may feel should be proper in the case thereafter should be addressed for the consideration of the Court. The only qualification is that the action of the Court must not impair the substantial rights of the accused, or the right of the People to due process of law. Whatever irregularity in the proceedings the private parties may raise should be addressed to the sound discretion of the trial court which has already acquired jurisdiction over the case. Certiorari, being an extraordinary writ, cannot be resorted to when there are other remedies available. IN THE CASE AT BAR, the OCAMPOs could file a Motion to Quash the Information under Rule 117 of the Rules of Court, or let the trial proceed where they can either file a demurrer to evidence or present their evidence to disprove the charges against them. It is well settled that criminal prosecutions may not be restrained or stayed by injunction, preliminary or final, subject to certain exceptions, e.g., when the determination of probable cause is done with grave abuse of discretion,12 or where a sham preliminary investigation was hastily conducted,13 or where it is necessary for the courts to do so for the orderly administration of justice or to prevent the use of the strong arm of the law in an oppressive and vindictive manner.14 None of these exceptions is present in the instant case. Hence, the Court of Appeals erred in granting private respondents' Petition for Certiorari and, worse, setting aside the Resolution of the Secretary of Justice.

PEOPLE v. NEPOMUCENO, 309 SCRA 466 Guillermo NEPOMUCENO was separately charged before the Regional Trial Court of Manila with parricide and with qualified illegal possession of firearm. The crime of parricide was alleged to have been committed with the use of an unlicensed firearm. NEPOMUCENO entered a plea of not guilty in each case. Judgment was rendered findings NEPOMUCENO guilty beyond reasonable doubt of the crime of parricide and sentencing him to suffer a prison term of forty years of reclusion perpetua. NEPOMUCENO appealed the judgment to the SC. The appealed judgment of conviction was affirmed. Meanwhile, the trial court proceeded with the case for qualified illegal possession of firearm. Judgment was promulgated holding that all the elements of the crime of aggravated illegal possession of firearm were present. The trial court applied the ruling in People v. Quijada that the killing of a person with the use of an illegally possessed firearm gives rise to two separate offenses, namely, (1) homicide or murder under the Revised Penal Code and (2) illegal possession of firearm in its aggravated form. Accordingly, the trial court convicted NEPOMUCENO of the violation of P.D. No. 1866, as amended by R.A. No. 8294, and sentenced him to suffer the penalty of death by lethal injection The judgment was forwarded to this Court for automatic review. ISSUE: WON NEPOMUCENO was properly convicted of the separate offense of Qualified Illegal Possession of Firearms? HELD: No. RATIO: NEPOMUCENO initially asks for the reversal of the challenged decision because the trial court erred in convicting him on the basis of "evidence by inference" and in ruling that circumstantial evidence showed that the accused had animus possidendi of the unrecovered firearm. Secondly, NEPOMUCENO asserts that this Court must allow the benefit of R.A. No. 8249 to take retroactive effect as to acquit him of the crime of qualified illegal possession of firearm. In the alternative, he asks for acquital because the trial court erred in finding that the prosecution proved an essential requisite of the offense, i.e., the accused possessed the firearm without the requisite of license or permit. The Office of the Solicitor General likewise asks for the reversal of the challenged decision and for the acquittal of NEPOMUCENO on these grounds: (1) the prosecution failed to prove that NEPOMUCENO had no authority or license to possess the firearm; and (2) the benefits of R.A.. No. 8294 should be given

retroactive effect, as such, if homicide or murder (parricide) is committed with the use of an unlicensed firearm, such use of an unlicensed firearm shall be considered as an aggravating circumstance and shall no longer be separately punished. The information alleged that the crime of illegal possession of firearm was committed BEFORE the approval of R.A. No. 8294. Under the amendatory law, if homicide or murder is committed with the use of an unlicensed firearm, such use of an unlicensed firearm shall be considered as an aggravating circumstance. Being clearly favorable to NEPOMUCENO, who is not a habitual criminal, the amendment to P.D. No. 1866 by R.A.. No. 8294 should be given retroactive effect in this case. Considering that NEPOMUCENO was in fact convicted in the case for parricide, and that his conviction was affirmed, it follows that NEPOMUCENO should be ACQUITTED in the case at bar. One final word: Even assuming that NEPOMUCENO could be separately punished for illegal possession or use of an unlicensed firearm, the imposition of the death penalty on him has no legal basis because at the time of the commission of the crime, the supreme penalty of death remained suspended under RA 7659. Conformably therewith, what the trial court could legally impose at that time was reclusion perpetua.

PEOPLE vs. LINING, 366 SCRA 25 (2001) Emelina ORNOS, fifteen (15) years old, came to visit her aunt Josephine at Sitio Buho, Barangay Nabuslot, Pinamalayan Oriental Mindoro. While in her aunts house, ORNOS was invited to a dance party to be held at the barangay basketball court. ORNOS accepted the invitation and went to the party accompanied by her aunt. ORNOS was later left alone by aunt, upon the promise that aunt would return later to fetch her. At around 12:30 AM, the party ended but Aunt still had not returned. So, ORNOS decided to go home alone. On her way, ORNOS was accosted by LINING and SALVACION, both of whom were known to her since they were her former neighbors. LINING poked a knife at ORNOSs breast and the two held her hands. She was dragged towards the ricefield and was forcibly carried to an unoccupied house owned by SALVACION. Inside the house, Lining removed EMELINAs t-shirt, pants and undergarments. She was pushed to the floor and while Salvacion was holding her hands and kissing her, Lining inserted his penis inside her vagina. Emelina shouted and tried to ward off her attackers, but to no avail. One RUSSEL heard her cries and tried to help her but he left when told not to interfere ("Huwag kang makialam"). After Lining had satisfied his lust, he held Emelinas hands and kissed her while Salvacion in turn inserted his penis inside her vagina. Thereafter, the two directed Emelina to put on her clothes. The accused then looked for a vehicle to transport Emelina to Barangay Maningcol. Emelina saw an opportunity to escape, and she returned to her aunts house. However, because of fear, as the accused threatened her that she would be killed if she would reveal what they did to her, she did not tell her aunt what transpired. At the house of her friend, EMELINA told her fathers friend (SELDA) about the rape incident and SELDA accompanied her to the barangay captain. Barangay captain was not in his house, so Selda brought Emelina to the Chief of Police. Emelina's statements were taken at the police station and she was subjected to a medical examination. The Chief of Police immediately ordered the arrest of Lining but Salvacion was able to escape. The medical exam revealed multiple healing contusions in her breast, neck as well as healed laceration on the hymen. Medical examiner testified that the contusions could have been caused by a blunt object, a forcible kiss or a bite, and that the fresh erosion along the vaginal canal could have been caused by an erect penis. LINING interposed a general denial and alibi.

The trial court found Gerry Lining guilty beyond reasonable doubt for the crime of forcible abduction with rape, and for another count of rape, meting upon him the supreme penalty of death. Hence this appeal ISSUE: WON LINNING is guilty of the crimes he was convicted for HELD: YES. Factual findings of the trial court deserves respect, if not finality, since the trial judge had the unique opportunity to observe the demeanor of the witnesses as they testify.The straightforward and candid testimony of Emelina Ornos, who was crying as she recalled her ordeal before the trial court, is certainly more credible than the testimonies of the defense witnesses. LINING has nothing to offer other than alibi. Unfortunately for him, alibi is weak in face of the positive identification by the victim of the perpetrator of the offense. Further, the testimonies of LINING and his witnesses are not consistent on some material points. The non-presentation of Russel to prove that he saw Emelina being raped does not weaken the cause of the prosecution since his testimony would at best only be corroborative. In rape cases, corroborative testimony is not absolutely necessary. The lone testimony of the victim may suffice to convict the rapist. The Court notes that neither the defense presented Russel to contradict the testimony of Emelina The medical finding that the victim was already a non-virgin, nor the fact that she had sexual relations before, would not matter. Even a woman of loose morals could still be a victim of rape, for the essence of rape is the carnal knowledge of a woman against her will and without her consent. Neither the absence of physical injuries negates the fact of rape since proof of physical injury is not an element of rape. Nevertheless, accused-appellant could only be convicted for the crime of rape, instead of the complex crime of forcible abduction with rape. The main objective of the accused when the victim was taken was to rape her. Hence, forcible abduction is absorbed in the crime of rape. Where the rape is committed by two or more persons, the imposable penalty ranges from reclusion perpetua to death; however, where there is no aggravating circumstance proved in the commission of the offense, the lesser penalty shall be applied. Finally, it should be stressed that one who clearly concurred with the criminal design of another and performed overt acts which led to the multiple rape committed is a co-conspirator. For this reason, LINING is deemed a co-conspirator

for the act of rape committed by his co-accused SALVACION and should accordingly be penalized therefor.

PILAPIL vs. IBAY-SOMERA Imelda Pilapil, a Filipino citizen, and Erich Ekkehard Geiling, a German national, were married in Germany. The couple lived together for some time in Malate, Manila where their only child, Isabella, was born Thereafter, marital discord set in, with mutual recriminations between the spouses, followed by a separation de facto between them. The disharmony between the spouses eventuated in GEILING initiating a divorce proceeding against PILAPIL in the Local Court in Germany. He claimed that there was failure of their marriage and that they had been living apart since 1982. PILAPIL, meanwhile, filed an action for legal separation, support and separation of property before the Regional Trial Court of Manila The German Local Court promulgated a decree of divorce. The custody of the child was granted to PILAPIL. Under German law, said court was legally competent for the divorce proceeding and that the dissolution of said marriage was legally founded on and authorized by the applicable law of that foreign jurisdiction More than five months after the issuance of the divorce decree, GEILING filed two complaints for adultery before the City Fiscal of Manila alleging that, while still married to him, PILAPIL "had an affair with a certain William Chia and with yet another man named Jesus Chua". Assistant Fiscal, after the corresponding investigation, recommended the dismissal of the cases on the ground of insufficiency of evidence. However, upon review, the City fiscal directed the filing of two complaints for adultery against PILAPIL. Two counts were raffled to different courts the adultery with Chua was raffled to Judge Cruz while the adultery with Chia was raffled to Judge Ibay-Somera. PILAPIL filed a petition with the Secretary of Justice asking that the aforesaid resolution of the city fiscal be set aside and the cases against her be dismissed. The Secretary of Justice gave due course to both petitions and directed the respondent city fiscal to inform the Department of Justice "if the accused have already been arraigned and if not yet arraigned, to move to defer further proceedings" and to elevate the entire records of both cases to his office for review. PILAPIL thereafter filed a motion in both criminal cases to defer her arraignment and to suspend further proceedings thereon. As a consequence, Judge Leonardo Cruz suspended proceedings but Judge Ibay-Somera merely reset the date of the arraignment. Before such scheduled date, PILAPIL moved (MOTION TO QUASH) for the cancellation of the arraignment and for the suspension of proceedings until after the

resolution of the petition for review then pending before the Secretary of Justice. Denied and they were ordered to be arraigned. CHIA entered a plea of not guilty while PILAPIL refused to be arraigned. Such refusal was considered by respondent judge SOMERA as direct contempt, she and her counsel were fined and the former was ordered detained until she submitted herself for arraignment. Later, PILAPIL entered a plea of not guilty. THUS, PILAPIL filed this special civil action for certiorari and prohibition seeking the annulment of the order of the lower court denying her motion to quash. The petition is anchored on the main ground that the court is without jurisdiction "to try and decide the charge of adultery, which is a private offense that cannot be prosecuted de officio, since the purported complainant, a foreigner, does not qualify as an offended spouse having obtained a final divorce decree under his national law prior to his filing the criminal complaint." The Supreme Court issued a TRO enjoining the Judge Somera from implementing the aforesaid order and from further proceeding with Criminal Case of adultery Meanwhile, SOJ issued a resolution directing the respondent city fiscal to move for the dismissal of the complaints against PILAPIL ISSUE: WON Judge SOMERA abused discretion in denying PILAPILs Motion to Quash and ordering her arraignment HELD: YES! RATIO: Under Article 344, RPC, the crime of adultery, as well as four other crimes against chastity, cannot be prosecuted except upon a sworn written complaint filed by the offended spouse. Compliance with this rule is a jurisdictional, and not merely a formal, requirement. The requirement for a sworn written complaint is jurisdictional since it is that complaint which starts the prosecutory proceeding and without which the court cannot exercise its jurisdiction to try the case. The law specifically provides that in prosecutions for adultery and Concubinage, the person who can legally file the complaint should be the offended spouse, and nobody else; unlike in the offenses of seduction, abduction, rape and acts of lasciviousness where the parents, grandparents or guardian of the offended party can do so. The State, as parens patriae, was also vested by the 1985 Rules of Criminal Procedure with the power to initiate the criminal action for a deceased or incapacitated victim in the aforesaid offenses of seduction, abduction, rape and acts of lasciviousness, in default of her parents, grandparents or guardian

Corollary to such exclusive grant of power to the offended spouse to institute the action, it necessarily follows that such initiator must have the status, capacity or legal representation to do so at the time of the filing of the criminal action. In the so-called "private crimes" or those which cannot be prosecuted de oficio, and the present prosecution for adultery is of such genre, the offended spouse assumes a more predominant role since the right to commence the action, or to refrain therefrom, is a matter exclusively within his power and option. This policy was adopted out of consideration for the aggrieved party who might prefer to suffer the outrage in silence rather than go through the scandal of a public trial. Hence, Article 344, RPC presupposes that the marital relationship is still subsisting at the time of the institution of the criminal action for, adultery. This is a logical consequence since the raison d'etre of said provision of law would be absent where the supposed offended party had ceased to be the spouse of the alleged offender at the time of the filing of the criminal case It is indispensable that the status and capacity of the complainant to commence the action be definitely established and, as already demonstrated, such status or capacity must indubitably exist as of the time he initiates the action. It would be absurd if his capacity to bring the action would be determined by his status before or subsequent to the commencement thereof, where such capacity or status existed prior to but ceased before, or was acquired subsequent to but did not exist at the time of, the institution of the case. After a divorce has been decreed, the innocent spouse no longer has the right to institute proceedings against the offenders where the statute provides that the innocent spouse shall have the exclusive right to institute a prosecution for adultery. Where, however, proceedings have been properly commenced, a divorce subsequently granted can have no legal effect on the prosecution of the criminal proceedings to a conclusion In cases of private nature, the status of the complainant vis-a-vis the accused must be determined as of the time the complaint was filed. Thus, the person who initiates the adultery case must be an offended spouse, and by this is meant that he is still married to the accused spouse, at the time of the filing of the complaint. IN THE CASE AT BAR, GEILING already obtained a valid divorce in his country when he filed the case. Said divorce and its legal effects may be recognized in the Philippines insofar as GEILING is concerned in view of the nationality principle in our civil law on the matter of status of persons. GEILING, being no longer the husband of PILAPIL, had no legal standing to commence the adultery case under the imposture that he was the offended spouse at the time he filed suit.

The allegation of GEILING that he could not have brought this case before the decree of divorce for lack of knowledge, even if true, is of no legal significance or consequence in this case. When GEILING initiated the divorce proceeding, he obviously knew that there would no longer be a family nor marriage vows to protect once a dissolution of the marriage is decreed. Neither would there be a danger of introducing spurious heirs into the family, which is said to be one of the reasons for the particular formulation of our law on adultery, since there would thenceforth be no spousal relationship to speak of. The severance of the marital bond had the effect of dissociating the former spouses from each other, hence the actuations of one would not affect or cast obloquy on the other.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Case Digests (Dan Fue Leung V IAC and Bearneza V Dequilla)Document3 pagesCase Digests (Dan Fue Leung V IAC and Bearneza V Dequilla)Amin JulkipliNo ratings yet

- PRIL DigestsDocument10 pagesPRIL DigestsAmin JulkipliNo ratings yet

- Case Digests (Dan Fue Leung V IAC and Bearneza V Dequilla)Document3 pagesCase Digests (Dan Fue Leung V IAC and Bearneza V Dequilla)Amin JulkipliNo ratings yet

- People's Homesite v. Jeremias (Digest)Document2 pagesPeople's Homesite v. Jeremias (Digest)Amin JulkipliNo ratings yet

- DIGEST - Pimentel v. AguirreDocument5 pagesDIGEST - Pimentel v. AguirreAmin JulkipliNo ratings yet

- Marcos BLBAR PDFDocument105 pagesMarcos BLBAR PDFAmin JulkipliNo ratings yet

- Selected Case Digests (Cause or Consideration)Document12 pagesSelected Case Digests (Cause or Consideration)Amin JulkipliNo ratings yet

- Selected Cases On "Law of The Case"Document5 pagesSelected Cases On "Law of The Case"Amin JulkipliNo ratings yet

- PHHC v. Jeremias and Other CasesDocument9 pagesPHHC v. Jeremias and Other CasesAmin JulkipliNo ratings yet

- Writ of Kalikasan (Rules of Procedure)Document13 pagesWrit of Kalikasan (Rules of Procedure)Amin JulkipliNo ratings yet

- Legal Regime For Peoples InitiativeDocument7 pagesLegal Regime For Peoples InitiativeAmin JulkipliNo ratings yet

- Towards A Comprehensive Policy On Missing Persons in Conflict Areas: Search, Recovery and Identification of The DeadDocument5 pagesTowards A Comprehensive Policy On Missing Persons in Conflict Areas: Search, Recovery and Identification of The DeadAmin JulkipliNo ratings yet

- Legal Regime For Peoples InitiativeDocument7 pagesLegal Regime For Peoples InitiativeAmin JulkipliNo ratings yet

- DIGEST - Pimentel v. AguirreDocument5 pagesDIGEST - Pimentel v. AguirreAmin JulkipliNo ratings yet

- DIGEST - Pimentel v. AguirreDocument5 pagesDIGEST - Pimentel v. AguirreAmin JulkipliNo ratings yet

- Legal Regime For Peoples InitiativeDocument7 pagesLegal Regime For Peoples InitiativeAmin JulkipliNo ratings yet

- ObliCon Case TriggersDocument12 pagesObliCon Case TriggersAmin JulkipliNo ratings yet

- SPECPRO AL Feb11Document2 pagesSPECPRO AL Feb11Amin JulkipliNo ratings yet

- DECONSTRUCTION OF CONSTITUTIONAL LIMITATIONS AND THE TARIFF REGIME OF THE PHILIPPINES: THE STRANGE PERSISTENCE OF A MARTIAL LAW SYNDROME By: Justice Florentino P. Feliciano (Ret.)Document4 pagesDECONSTRUCTION OF CONSTITUTIONAL LIMITATIONS AND THE TARIFF REGIME OF THE PHILIPPINES: THE STRANGE PERSISTENCE OF A MARTIAL LAW SYNDROME By: Justice Florentino P. Feliciano (Ret.)Amin JulkipliNo ratings yet

- Torts in Common LawDocument7 pagesTorts in Common LawAmin JulkipliNo ratings yet

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Republic vs. O.G. Holdings Corp. G.R. No. 189290, Nov. 29,2017 The FactsDocument2 pagesRepublic vs. O.G. Holdings Corp. G.R. No. 189290, Nov. 29,2017 The FactsBingoheartNo ratings yet

- CIVPRO Rural Bank of Calinog (Iloilo), Inc. vs. Court of AppealsDocument1 pageCIVPRO Rural Bank of Calinog (Iloilo), Inc. vs. Court of AppealsKim SimagalaNo ratings yet

- Narzoles v. NLRCDocument2 pagesNarzoles v. NLRCK FelixNo ratings yet

- Juan v. JuanDocument3 pagesJuan v. JuanKaren Joy MasapolNo ratings yet

- Third Division: Decision DecisionDocument8 pagesThird Division: Decision DecisionMarilyn MalaluanNo ratings yet

- People V PuigDocument9 pagesPeople V PuigCelest AtasNo ratings yet

- GBL 9 Soriano V PeopleDocument14 pagesGBL 9 Soriano V PeopleCol. McCoyNo ratings yet

- Rule 65 Case NotesDocument26 pagesRule 65 Case NotesMichelle Mae Mabano100% (1)

- Labor Congress vs. NLRC PDFDocument23 pagesLabor Congress vs. NLRC PDFHyacinthNo ratings yet

- Malabanan vs. Sandiganbayan 834 SCRA 21 02aug2017Document28 pagesMalabanan vs. Sandiganbayan 834 SCRA 21 02aug2017GJ LaderaNo ratings yet

- Modes of Appeal from RTC Decisions ExplainedDocument5 pagesModes of Appeal from RTC Decisions ExplainedJANE MARIE DOROMALNo ratings yet

- Holy Cross of Davao College, Inc. vs. JoaquinDocument9 pagesHoly Cross of Davao College, Inc. vs. Joaquin유니스No ratings yet

- Tahanan Devp Vs CA G.R. No. L-55771Document7 pagesTahanan Devp Vs CA G.R. No. L-55771Arlene Taba FerrerNo ratings yet

- SC rules civil case does not raise prejudicial question to stop criminal caseDocument9 pagesSC rules civil case does not raise prejudicial question to stop criminal caseCJ N PiNo ratings yet

- 2011 NLRC Rules of Procedure Notes and CasesDocument62 pages2011 NLRC Rules of Procedure Notes and CasesStef Macapagal100% (3)

- 21 Badillo v. CADocument7 pages21 Badillo v. CAChescaSeñeresNo ratings yet

- People V SandiganbayanDocument50 pagesPeople V SandiganbayanAlvin HilarioNo ratings yet

- 50 Surigao Del Norte Electric Coop., Inc. v. ERCDocument23 pages50 Surigao Del Norte Electric Coop., Inc. v. ERCdos2reqjNo ratings yet

- Labor DigestsDocument91 pagesLabor DigestsAnne Vallarit100% (2)

- 05 Santiago Land Development Company v. CADocument2 pages05 Santiago Land Development Company v. CAAliyah RojoNo ratings yet

- Evidence Conflict Cases Compilation Batch 1Document341 pagesEvidence Conflict Cases Compilation Batch 1Jpakshyiet100% (1)

- The Alexandra CondominiumDocument2 pagesThe Alexandra CondominiumjmNo ratings yet

- Land Titles and Deeds-Case Digests-Espina-M7Document15 pagesLand Titles and Deeds-Case Digests-Espina-M7NiellaNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court Rules Tape Recordings InadmissibleDocument3 pagesSupreme Court Rules Tape Recordings InadmissibleDONNIE RAY SOLONNo ratings yet

- Palma Gil - Go CaseDocument3 pagesPalma Gil - Go CaseNikki BarenaNo ratings yet

- 5.gsis VS Simeon TanedoDocument13 pages5.gsis VS Simeon TanedoViolet BlueNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court Rules in Favor of Farmer's Right to Repurchase LandDocument68 pagesSupreme Court Rules in Favor of Farmer's Right to Repurchase LandLance QuialquialNo ratings yet

- E. Lim v. Executive SecretaryDocument43 pagesE. Lim v. Executive SecretaryJoshuaMaulaNo ratings yet

- CIR vs. Primetown (PFR)Document2 pagesCIR vs. Primetown (PFR)Dave Jonathan MorenteNo ratings yet

- 4Document4 pages4Victor RamirezNo ratings yet