Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Transpo To Print

Uploaded by

arinojacobOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Transpo To Print

Uploaded by

arinojacobCopyright:

Available Formats

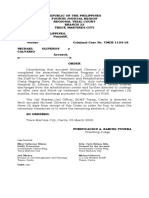

Tiu vs.

Arriesgado 437 SCRA 426 FACTS: At about 10:00 pm, the cargo truck marked Condor Hollow Blocks and General Merchandise" was loaded with firewood in Bogo, Cebu and left for Cebu City. Upon reaching Sitio Aggies, Poblacion Compostela, Cebu, just as the truck passed over the bridge, one of its rear tires exploded. The driver, Sergio Pedrano, then parked along the right side of the bridge and removed the damaged tire to have it vulcanized at a nearby shop. Pedrano left his helper, Jose Militante Jr. to keep watch over the stalled vehicle, and instructed the latter to place a spare tire 6 fathoms behind the stalled truck to serve as a warning for oncoming vehicles. The truck's tail lights were also left on. At abount 4:45 am., D rough Riders Passenger bus driven by Virgilio te Las Pinas was crushing along the national highway of Sitio Aggies also bound for Cebu City. Among its passengers were the Sposes Pedro A. Arriesgado and Felisa Pepito Arriesgado, who were seated at the right side of the bus. As the bus was approaching the bridge, Las Pinas saw the stalled truck. He applied the brakes and tried to swerve to the left to avoid hitting the truck. But it was too late; the bus rammed into the truck's left rear. Pedro Arriesgado lost consciousness and suffered a fracture in his colles. His wife Felisa died after being transferred to Island Medical Center. Arriesgado then filed a complaint against Wiliam Tiu, operator of D Rough and his driver Las Pinas for breach of contract of carriage. ISSUE: Whether the doctrine of last clear chance is applicable as the petitioner asserts. HELD: No way! Contrary to the petitioner's contention, the principle of last clear chance is inapplicable in the instant case, as it only applies in a suit between the owners and drivers of two colliding vehicles. It does not arise where the passenger demands responsibility from the carrier to enforce its contractual obligations, for it would be inequitable to exempt the negligent driver and its owner on the ground that the other driver was likewise guilty of negligence. The common law notion of last clear chance permitted courts to grant recovery to a plaintiff who has also been negligent provided that the defendant had the last clear chance to avoid the casualty and failed to do so. PAJARITO VS. SENERIS 87 SCRA 275 FACTS: Joselito Aizon, the driver-employee of an Isuzu Passenger Bus operated by Felipe Aizon, caused the bus to turn turtle as a result of which two of his passengers on board sustained injuries which caused their death. Thereafter, an information was filed in the CFI of Zamboanga City charging the accused with double homicide through reckless imprudence. Upon arraignment, respondent pleaded guilty and the court rendered a judgment convicting him and to pay the amount of P12, 000.00. Due to the insolvency of the accused, petitioner Lucia S. Pajarito, mother of the deceased passenger, filed with the court a motion for the issuance of subsidiary writ of execution against the operator Felipe Aizon. The court denied petitioner's motion for subsidiary writ of execution. ISSUE: WON the trial court erred in denying the motion for subsidiary writ of execution. HELD: Yes, the institution of the criminal action carries with it the institution of the civil action arising therefrom. Considering that Felipe Aizon does not deny that he was the registered operator of the bus, the proceeding for the enforcement of the subsidiary civil liability may be considered as part of the proceeding for the execution of judgment. Pursuant to Article 103, in relation to Article 102, of the Revised Penal Code, an employer may be subsidiary liable for the employee's civil liability in a criminal action when: (1) the employer is engaged in any kind of industry; (2) the employee committed the offense in the discharge of his duties; and (3) he is insolvent and has not satisfied his civil liability. 2 The subsidiary civil liability of the employer, however, arises only after conviction of the employee in the criminal case. British Airways v. Court of Appeals G.R. No. 121824 Facts: On April 6, 1989, Mahtani decided to visit his relative in Bombay, India. In anticipation of his visit, he obtained the services of a certain Mr. Gemar to prepare his travel plan. Since british Airways had no ticket flights from Manila to Bombay, Maktani had to take a connecting flight to Bombay on board British Airways. Prior to his departure, Maktani checked in the PAL counter in Manila his two pieces of luggage containing his clothing and personal effects, confident that upon reaching Hong Kong, the same would be transferred to the BA flight bound for Bombay, Unfortunately, when Maktani arrived in Bombay, he discovered that his luggage was missing and that upon inquiry from the BA representatives, he was told that the same might have been diverted to London. After plaintiff waiting for his luggage for one week, BA finally advised him to file a claim accomplishing the property. Issue: Whether or not defendant BA is liable for compulsory damages and attorneys fee, as well as the dismissal of its third party complaint against PAL Held: The contract of transportation was exclusively between Maktani and BA. The latter merely endorsing the Manila to Hong Kong log of the formers journey to PAL, as its subcontractor or agent. Conditions of contacts was one of continuous air transportation from Manila to Bombay. The Court of Appeals should have been cognizant of the wellsettled rule that an agent is also responsible for any negligence in the performance of its function and is liable for damages which the principal may suffer by reason of its negligent act. Since the instant petition was based on breach of contract of carriage, Maktani can only sue BA and not PAL, since the latter was not a party in the contract. DANGWA TRANSPORTATION vs. COURT OF APPEALS FACTS: Private respondents filed a complaint for damages against petitioners for the death of Pedrito Cudiamat as a result of a vehicular accident which occurred on March 25, 1985 at Marivic, Sapid, Mankayan, Benguet. Petitioner Theodore M. Lardizabal was driving a passenger bus belonging to petitioner

corporation in a reckless and imprudent manner and without due regard to traffic rules and regulations and safety to persons and property, it ran over its passenger, Pedrito Cudiamat. Petitioners alleged that they had observed and continued to observe the extraordinary diligence and that it was the victim's own carelessness and negligence which gave rise to the subject incident. RTC pronounced that Pedrito Cudiamat was negligent, which negligence was the proximate cause of his death. However, Court of Appeals set aside the decision of the lower court, and ordered petitioners to pay private respondents damages due to negligence. ISSUE: WON the CA erred in reversing the decision of the trial court and in finding petitioners negligent and liable for the damages claimed. HELD: CA Decision AFFIRMED The testimonies of the witnesses show that that the bus was at full stop when the victim boarded the same. They further confirm the conclusion that the victim fell from the platform of the bus when it suddenly accelerated forward and was run over by the rear right tires of the vehicle. Under such circumstances, it cannot be said that the deceased was guilty of negligence. It is not negligence per se, or as a matter of law, for one attempt to board a train or streetcar which is moving slowly. An ordinarily prudent person would have made the attempt board the moving conveyance under the same or similar circumstances. The fact that passengers board and alight from slowly moving vehicle is a matter of common experience both the driver and conductor in this case could not have been unaware of such an ordinary practice. Common carriers, from the nature of their business and reasons of public policy, are bound to observe extraordinary diligence for the safety of the passengers transported by the according to all the circumstances of each case. A common carrier is bound to carry the passengers safely as far as human care and foresight can provide, using the utmost diligence very cautious persons, with a due regard for all the circumstances. It has also been repeatedly held that in an action based on a contract of carriage, the court need not make an express finding of fault or negligence on the part of the carrier in order to hold it responsible to pay the damages sought by the passenger. By contract of carriage, the carrier assumes the express obligation to transport the passenger to his destination safely and observe extraordinary diligence with a due regard for all the circumstances, and any injury that might be suffered by the passenger is right away attributable to the fault or negligence of the carrier. This is an exception to the general rule that negligence must be proved, and it is therefore incumbent upon the carrier to prove that it has exercised extraordinary diligence as prescribed in Articles 1733 and 1755 of the Civil Code. Del Prado v. Meralco Facts: Teodorico Florenciano, Meralcos motorman, was driving the companys street car along Hidalgo Street. Plaintiff Ignacio Del Prado ran across the street to catch the car. The motorman eased up but did not put the car into complete stop. Plaintiff was able to get hold of the rail and step his left foot when the

car accelerated. As a result, plaintiff slipped off and fell to the ground. His foot was crushed by the wheel of the car. He filed a complaint for culpa contractual. Issues: (1) Whether the motorman was negligent (2) Whether Meralco is liable for breach of contract of carriage (3) Whether there was contributory negligence on the part of the plaintiff Held: (1) We may observe at the outset that there is no obligation on the part of a street railway company to stop its cars to let on intending passengers at other points than those appointed for stoppage. Nevertheless, although the motorman of this car was not bound to stop to let the plaintiff on, it was his duty to do no act that would have the effect of increasing the plaintiff's peril while he was attempting to board the car. The premature acceleration of the car was, in our opinion, a breach of this duty. (2) The relation between a carrier of passengers for hire and its patrons is of a contractual nature; and a failure on the part of the carrier to use due care in carrying its passengers safely is a breach of duty (culpa contractual). Furthermore, the duty that the carrier of passengers owes to its patrons extends to persons boarding the cars as well as to those alighting therefrom. Where liability arises from a mere tort (culpa aquiliana), not involving a breach of positive obligation, an employer, or master, may exculpate himself by proving that he had exercised due diligence to prevent the damage; whereas this defense is not available if the liability of the master arises from a breach of contractual duty (culpa contractual). In the case before us the company pleaded as a special defense that it had used all the diligence of a good father of a family to prevent the damage suffered by the plaintiff; and to establish this contention the company introduced testimony showing that due care had been used in training and instructing the motorman in charge of this car in his art. But this proof is irrelevant in view of the fact that the liability involved was derived from a breach of obligation. (3) It is obvious that the plaintiff's negligence in attempting to board the moving car was not the proximate cause of the injury. The direct and proximate cause of the injury was the act of appellant's motorman in putting on the power prematurely. Again, the situation before us is one where the negligent act of the company's servant succeeded the negligent act of the plaintiff, and the negligence of the company must be considered the proximate cause of the injury. The rule here applicable seems to be analogous to, if not identical with that which is sometimes referred to as the doctrine of "the last clear chance." In accordance with this doctrine, the contributory negligence of the party injured will not defeat the action if it be shown that the defendant might, by the exercise of reasonable care and prudence, have avoided the consequences of the negligence of the injured party. The negligence of the plaintiff was, however, contributory to the accident and must be considered as a mitigating circumstance. Sweet Lines Inc. v. Teves G.R. No. L-37750 Facts: Private respondents Atty. Leovigildo Tandog and Rogelio Tirog bought tickets at the branch office of the

petitioner, a shipping company transporting inter-island passengers and cargoes, at the Cagayan de Oro City. Respondents were to board M/S Sweet Hope,however upon learning that it will not be proceeding to Bohol they decided to board M/S Sweet Town. On such vessel the respondents agreed to hide at the cargo section to avoid inspection of the officers of the Philippine Coast guard. After suffering the inconviences in the cargo section and paying other tickets because those that are in their possession were no honored. The respondents sued the petitioners in the Court of First Instance of Misamis Oriental for breach of contract of carriage in the alleged sum of P110,000.00. Petitioners moved for the dismissal of the complaint on the ground of improper venue for Conditon No. 14 printed on the ticket essentially provides that any actions arising out of the ticket will be filed at the competent court of Cebu. The trial court ruled in favor of the respondents after denying the motion for dismissal. Having exhausted all the remedies available and still failed to obtain a ruling in their favor, the petitioner filed this instant petition for prohibition with preliminary injunction. The Supreme Court gave due course to their petition and required them to submit their memoranda in support of their respective contention. Respondents contend that condition No. 14 is not a part of the contract of carriage and that it is an independent contract requiring the mutual consent of the parties. In the case at bar the consent of the respondents was not sought it was imposed on them unilaterally. Venue of actions can only be waived if there is a written agreement of the parties. Condition No.14 not being agreed to by the respondents is not valid and enforceable. Supposing that it is otherwise, it is not exclusive and does not, therefore exclude the filing of the action in Misamis Oriental. Petioner contend that condition No. 14 is valid and enforceable because private respondents acceded to it when they purchased passage tickets and it is an effective waiver of venue, valid and binding as such, since it is printed in bold and capital letters and not in fine print and merely assigns the place where the action arising from the contract is instituted. That condition No. 14 is unequivocal and mandatory, the words and phrases any and all, irrespective of where it is issued, and shall leave no doubt that the intention of Condition No. 14 is to fix the venue in the City of Cebu, to the exclusion of all other places. Issue: Whether or not condition No. 14 is valid and enforceable. Held: Condition No. 14 is subversive of public policy on transfers of venue of actions. For, although venue may be changed or transferred from one province to another by agreement of the parties in writing pursuant to Rule 4, Section 3, of the Rules of Court, such an agreement will not be held valid where it practically negates the action of the claimants, such as the private respondents herein. The philosophy underlying the provisions on transfer of venue of actions is the convenience of the plaintiffs as well as his witnesses and to promote the ends of justice. Considering the expense and trouble a passenger residing outside of Cebu City would incur to prosecute a claim in the City of Cebu, he would most probably decide not to file the action at all. The condition will thus defeat, instead of enhance, the ends of justice. Upon the other hand, petitioner has branches or offices in the respective ports of call of its vessels and can afford to litigate in any of

these places. Hence, the filing of the suit in the CFI of Misamis Oriental, as was done in the instant case, will not cause inconvience to, much less prejudice, petitioner. Public policy is . . . that principle of the law which holds that no subject or citizen can lawfully do that which has a tendency to be injurious to the public or against the public good . . .. Under this principle . . . freedom of contract or private dealing is restricted by law for the good of the public. Clearly, Condition No. 14, if enforced, will be subversive of the public good or interest, since it will frustrate in meritorious cases, actions of passenger claimants outside of Cebu City, thus placing petitioner company at a decided advantage over said persons, who may have perfectly legitimate claims against it. The said condition should, therefore, be declared void and unenforceable, as contrary to public policy to make the courts accessible to all who may have need of their services. ABOITIZ SHIPPING CORPORATION vs. COURT OF APPEALS, et al FACTS: Anacleto Viana boarded the vessel M/V Antonia, owned by Aboitiz Shipping Corporation, at the port at San Jose, Occidental Mindoro, bound for Manila. After said vessel had landed, the Pioneer Stevedoring Corporation took over the exclusive control of the cargoes loaded on said vessel pursuant to the Memorandum of Agreement between Pioneer and petitioner Aboitiz. The crane owned by Pioneer was placed alongside the vessel and one (1) hour after the passengers of said vessel had disembarked, it started operation by unloading the cargoes from said vessel. While the crane was being operated, Anacleto Viana who had already disembarked from said vessel obviously remembering that some of his cargoes were still loaded in the vessel, went back to the vessel, and it was while he was pointing to the crew of the said vessel to the place where his cargoes were loaded that the crane hit him, pinning him between the side of the vessel and the crane. He was thereafter brought to the hospital where he later expired three (3) days thereafter. Private respondents Vianas filed a complaint for damages against petitioner for breach of contract of carriage. Aboitiz denied responsibility contending that at the time of the accident, the vessel was completely under the control of respondent Pioneer Stevedoring Corporation as the exclusive stevedoring contractor of Aboitiz, which handled the unloading of cargoes from the vessel of Aboitiz. ISSUE: Whether or not Aboitiz is negligent and is thus liable for the death. HELD: Yes. x x x [T]he victim Anacleto Viana guilty of contributory negligence, but it was the negligence of Aboitiz in prematurely turning over the vessel to the arrastre operator for the unloading of cargoes which was the direct, immediate and proximate cause of the victim's death. The rule is that the relation of carrier and passenger continues until the passenger has been landed at the port of destination and has left the vessel owner's dock or premises. 11 Once created, the relationship will not ordinarily terminate until the

passenger has, after reaching his destination, safely alighted from the carrier's conveyance or had a reasonable opportunity to leave the carrier's premises. All persons who remain on the premises a reasonable time after leaving the conveyance are to be deemed passengers, and what is a reasonable time or a reasonable delay within this rule is to be determined from all the circumstances, and includes a reasonable time to see after his baggage and prepare for his departure. 12 The carrierpassenger relationship is not terminated merely by the fact that the person transported has been carried to his destination if, for example, such person remains in the carrier's premises to claim his baggage. It is apparent from the foregoing that what prompted the Court to rule as it did in said case is the fact of the passenger's reasonable presence within the carrier's premises. That reasonableness of time should be made to depend on the attending circumstances of the case, such as the kind of common carrier, the nature of its business, the customs of the place, and so forth, and therefore precludes a consideration of the time element per se without taking into account such other factors. It is thus of no moment whether in the cited case of La Mallorca there was no appreciable interregnum for the passenger therein to leave the carrier's premises whereas in the case at bar, an interval of one (1) hour had elapsed before the victim met the accident. The primary factor to be considered is the existence of a reasonable cause as will justify the presence of the victim on or near the petitioner's vessel. We believe there exists such a justifiable cause. It is of common knowledge that, by the very nature of petitioner's business as a shipper, the passengers of vessels are allotted a longer period of time to disembark from the ship than other common carriers such as a passenger bus. With respect to the bulk of cargoes and the number of passengers it can load, such vessels are capable of accommodating a bigger volume of both as compared to the capacity of a regular commuter bus. Consequently, a ship passenger will need at least an hour as is the usual practice, to disembark from the vessel and claim his baggage whereas a bus passenger can easily get off the bus and retrieve his luggage in a very short period of time. Verily, petitioner cannot categorically claim, through the bare expedient of comparing the period of time entailed in getting the passenger's cargoes, that the ruling in La Mallorca is inapplicable to the case at bar. On the contrary, if we are to apply the doctrine enunciated therein to the instant petition, we cannot in reason doubt that the victim Anacleto Viana was still a passenger at the time of the incident. When the accident occurred, the victim was in the act of unloading his cargoes, which he had every right to do, from petitioner's vessel. As earlier stated, a carrier is duty bound not only to bring its passengers safely to their destination but also to afford them a reasonable time to claim their baggage. La Mallorca v. CA Facts: Mariano Beltran and his family rode a bus owned by petitioner. Upon reaching their desired destination, they alighted from the bus. But Mariano returned to get their baggage. His youngest daughter followed him without his knowledge. When he stepped into the bus again, it suddenly accelerated. Marianos daughter was found dead. The bus ran over her. Issue: Whether the liability of a common carrier extends even after the passenger had alighted

Held: The relation of carrier and passenger does not cease at the moment the passenger alights from the carriers vehicle at a place selected by the carrier at the point of destination, but continues until the passenger has had a reasonable time or reasonable opportunity to leave the current premises. Alberta Yobido and Cresencio Yobido v. CA, Leny Tumboy, Ardee Tumboy and Jasmin Tumboy G.R. No. 113003 October 17, 1997 FACTS: Spouses Tito and Leny Tumboy and their minor children named Ardee and Jasmin, boarded a Yobido Liner bus bound for Davao City. Along the trip, the left front tire of the bus exploded. The bus fell into a ravine around 3 ft. from the road and struck a tree. The incident resulted in the death of Tito and physical injuries to other passengers. Factual backdrop based on testimony of Leny: the winding road the bus traversed was not cemented and was wet due to the rain; it was rough with crushed rocks. The bus which was full of passengers had cargoes on top. Since it was running fast, (at a speed of 50-60kph based on another witness testimony) she cautioned the driver to slow down but he merely stared at her through the mirror. A complaint for breach of contract of carriage was filed by Leny and her children against Alberta Yobido, the owner of the bus, and Cresencio Yobido, its driver; Yobidos raised the affirmative defense of caso fortuito; they also filed a third-party complaint against Philippine Phoenix Surety and Insurance, Inc. Upon a finding that the third party defendant was not liable under the insurance contract, the lower court dismissed the third party complaint. ISSUE: WON the tire blowout was a caso fortuito as to exempt Yobidos from liability HELD: No. tire blowout - mechanical defect of the conveyance or a fault in its equipment which was easily discoverable if the bus had been subjected to a more thorough or rigid check-up before it took to the road when a passenger boards a common carrier, he takes the risks incidental to the mode of travel he has taken. After all, a carrier is not an insurer of the safety of its passengers and is not bound absolutely and at all events to carry them safely and without injury. However, when a passenger is injured or dies while travelling, the law presumes that the common carrier is negligent. (see Art. 1756) Art. 1755 provides that a common carrier is bound to carry the passengers safely as far as human care and foresight can provide, using the utmost diligence of very cautious persons, with a due regard for all the circumstances. In culpa contractual, once a passenger dies or is injured, the carrier is presumed to have been at fault or to have acted negligently. This disputable presumption may only be overcome by evidence that the carrier had observed extraordinary diligence as prescribed by Arts. 1733, 1755 and 1756 or that the death or injury of the passenger was due to a fortuitous event. characteristics of fortuitous event: a) the cause of the unforeseen and unexpected occurrence, or the failure of the debtor to comply with his obligations, must be independent of human will; b) it must be impossible to foresee the event which constitutes the caso fortuito, or if it can be foreseen, it must be impossible to avoid; c) the occurrence must be such

as to render it impossible for the debtor to fulfill his obligation in a normal manner; and d) the obligor must be free from any participation in the aggravation of the injury resulting to the creditor Art 1174: no person shall be responsible for a fortuitous event which could not be foreseen, or which, though foreseen, was inevitable the explosion of the new tire may not be considered a fortuitous event; there are human factors involved in the situation; the fact that the tire was new did not imply that it was entirely free from manufacturing defects or that it was properly mounted on the vehicle Baliwag Transit vs. CA (GR 116110, 15 May 1996) FACTS: On 31 July 1980, Leticia Garcia, and her 5-year old son, Allan Garcia, boarded Baliwag Transit Bus 2036 bound for Cabanatuan City driven by Jaime Santiago. They took the seat behind the driver. At about 7:30 p.m., in Malimba, Gapan, Nueva Ecija, the bus passengers saw a cargo truck, owned by A & J Trading, parked at the shoulder of the national highway. Its left rear portion jutted to the outer lane, as the shoulder of the road was too narrow to accommodate the whole truck. A kerosene lamp appeared at the edge of the road obviously to serve as a warning device. The truck driver, and his helper were then replacing a flat tire. Bus driver Santiago was driving at an inordinately fast speed and failed to notice the truck and the kerosene lamp at the edge of the road. Santiagos passengers urged him to slow down but he paid them no heed. Santiago even carried animated conversations with his co-employees while driving. When the danger of collision became imminent, the bus passengers shouted Babangga tayo!. Santiago stepped on the brake, but it was too late. His bus rammed into the stalled cargo truck killing him instantly and the trucks helper, and injury to several others among them herein respondents. Thus, a suit was filed against Baliwag Transit, Inc., A & J Trading and Julio Recontique for damages in the RTC of Bulacan. The trial court ordered Baliwag, A & J Trading and Recontique to pay jointly and severally the Garcia spouses the following: (1) P25,000.00 hospitalization and medication fee, (2) P450,000.00 loss of earnings in eight (8) years, (3) P2,000.00 for the hospitalization of their son Allan Garcia, (4) P50,000.00 moral damages, and (5) P30,000.00 attorney's fee. On appeal, the Court of Appeals modified the trial court's Decision by absolving A & J Trading from liability and by reducing the award of attorney's fees to P10,000.00 and loss of earnings to P300,000.00, respectively. ISSUE: Is the amount of damages awarded by the Court of Appeals to the Garcia spouses correct? HELD: Yes. The propriety of the amount awarded as hospitalization and medical fees. The award of P25,000.00 is not supported by the evidence on record. The Garcias presented receipts marked as Exhibits "B-1 " to "B-42" but their total amounted only to P5,017.74. To be sure, Leticia testified as to the extra amount spent for her medical needs but without more reliable evidence, her lone testimony cannot justify the award of

P25,000.00. To prove actual damages, the best evidence available to the injured party must be presented. The court cannot rely on uncorroborated testimony whose truth is suspect, but must depend upon competent proof that damages have been actually suffered. Thus, we reduce the actual damages for medical and hospitalization expenses to P5,017.74. The award of moral damages is in accord with law. In a breach of contract of carriage, moral damages are recoverable if the carrier, through its agent, acted fraudulently or in bad faith. The evidence shows the gross negligence of the driver of Baliwag bus which amounted to bad faith. Without doubt, Leticia and Allan experienced physical suffering, mental anguish and serious anxiety by reason of the accident. Philippine National Railways (PNR) vs. CA (GR L-55347, 4 October 1985) Facts: On 10 September 1972, at about 9:00 p.m., Winifredo Tupang, husband of Rosario Tupang, boarded Train 516 of the Philippine National Railways at Libmanan, Camarines Sur, as a paying passenger bound for Manila. Due to some mechanical defect, the train stopped at Sipocot, Camarines Sur, for repairs, taking some two hours before the train could resume its trip to Manila. Unfortunately, upon passing Iyam Bridge at Lucena, Quezon, Winifredo Tupang fell off the train resulting in his death. The train did not stop despite the alarm raised by the other passengers that somebody fell from the train. Instead, the train conductor, Perfecto Abrazado, called the station agent at Candelaria, Quezon, and requested for verification of the information. Police authorities of Lucena City were dispatched to the Iyam Bridge where they found the lifeless body of Winifredo Tupang. As shown by the autopsy report, Winifredo Tupang died of cardio-respiratory failure due to massive cerebral hemorrhage due to traumatic injury. Tupang was later buried in the public cemetery of Lucena City by the local police authorities. Upon complaint filed by the deceaseds widow, Rosario Tupang, the then CFI Rizal, after trial, held the PNR liable for damages for breach of contract of carriage and ordered it to pay Rosario Tupang the sum of P12,000.00 for the death of Winifredo Tupang, plus P20,000.00 for loss of his earning capacity, and the further sum of P10,000.00 as moral damages, and P2,000.00 as attorneys fees, and cost. On appeal, the Appellate Court sustained the holding of the trial court that the PNR did not exercise the utmost diligence required by law of a common carrier. It further increased the amount adjudicated by the trial court by ordering PNR to pay the Rosario Tupang an additional sum of P5,000,00 as exemplary damages. Moving for reconsideration of the above decision, the PNR raised for the first time, as a defense, the doctrine of state immunity from suit. The motion was denied. Hence the petition for review. Issue: WON there was contributory negligence on the part of Tupang. Held: PNR has the obligation to transport its passengers to their destinations and to observe extraordinary diligence in doing so. Death or any injury suffered by any of its passengers gives rise to the presumption that it was negligent in the performance of its obligation under the contract of carriage.

PNR failed to overthrow such presumption of negligence with clear and convincing evidence, inasmuch as PNR does not deny, (1) that the train boarded by the deceased Winifredo Tupang was so overcrowded that he and many other passengers had no choice but to sit on the open platforms between the coaches of the train, (2) that the train did not even slow down when it approached the Iyam Bridge which was under repair at the time, and (3) that neither did the train stop, despite the alarm raised by other passengers that a person had fallen off the train at Iyam Bridge. While PNR failed to exercise extraordinary diligence as required by law, it appears that the deceased was chargeable with contributory negligence. Since he opted to sit on the open platform between the coaches of the train, he should have held tightly and tenaciously on the upright metal bar found at the side of said platform to avoid falling off from the speeding train. Such contributory negligence, while not exempting the PNR from liability, nevertheless justified the deletion of the amount adjudicated as moral damages. The Supreme Court modified the decision of the appellate court by eliminating therefrom the amounts of P10,000.00 and P5,000.00 adjudicated as moral and exemplary damages, respectively; without costs. Pestano v. Sumayang Panganiban, J.G.R. No. 139875. December 4, 2000 (Respondeat Superior) FACTS At 2:00 oclock on the afternoon of August 9, 1986, Ananias Sumayang was riding a motorcycle along the national highway in Ilihan, Tabagon, Cebu. Riding with him was his friend Manuel Romagos. As they came upon a junction, they were hit by a passenger bus driven by Petitioner Gregorio Pestao and owned by Petitioner Metro Cebu Autobus Corporation, which had tried to overtake them, sending the motorcycle and its passengers hurtling upon the pavement. Both Sumayang and Romagos were rushed to the hospital in Sogod, where Sumayang was pronounced dead on arrival. Romagos was transferred to the Cebu Doctors Hospital, but he died the day after. The heirs of Sumayang instituted criminal action against Pestano and filed an action for damages against the driver, Pestano and Metro Cebu as the owner and operator of the bus. The CA and RTC ruled that Pestano was negligent and is therefore liable criminally and civilly. The appellate court opined that Metro Cebu had shown laxity in the conduct of its operations and in the supervision of its employees. By allowing the bus to ply its route despite the defective speedometer, said petitioner showed its indifference towards the proper maintenance of its vehicles. Having failed to observe the extraordinary diligence required of public transportation companies, it was held vicariously liable to the victims of the vehicular accident. ISSUES & ARGUMENTS W/N the CA erred in holding the bus owner and operator vicariously liable HOLDING & RATIO DECIDENDI The Court of Appeals is correct in holding the bus owner and operator vicariously liable. Under Articles 2180 and 2176 of the Civil Code, owners and managers are responsible for damages caused by their employees. When an injury is caused by the negligence of a servant or an employee, the master or employer is presumed to be negligent either in the selection or

in the supervision of that employee. This presumption may be overcome only by satisfactorily showing that the employer exercised the care and the diligence of a good father of a family in the selection and the supervision of its employee. The CA said that allowing Pestao to ply his route with a defective speedometer showed laxity on the part of Metro Cebu in the operation of its business and in the supervision of its employees. The negligence alluded to here is in its supervision over its driver, not in that which directly caused the accident. The fact that Pestao was able to use a bus with a faulty speedometer shows that Metro Cebu was remiss in the supervision of its employees and in the proper care of its vehicles. It had thus failed to conduct its business with the diligence required by law. Trans-Asia Shipping Lines vs. CA (GR 118126, 4 March 1996) FACTS: Respondent Atty. Renato Arroyo, a public attorney, bought a ticket from herein petitioner for the voyage of M/V Asia Thailand vessel to Cagayan de Oro City from Cebu City on November 12, 1991. At around 5:30 in the evening of November 12, 1991, respondent boarded the M/V Asia Thailand vessel during which he noticed that some repairs were being undertaken on the engine of the vessel. The vessel departed at around 11:00 in the evening with only one (1) engine running. After an hour of slow voyage, the vessel stopped near Kawit Island and dropped its anchor thereat. After half an hour of stillness, some passengers demanded that they should be allowed to return to Cebu City for they were no longer willing to continue their voyage to Cagayan de Oro City. The captain acceded to their request and thus the vessel headed back to Cebu City. In Cebu City, plaintiff together with the other passengers who requested to be brought back to Cebu City, were allowed to disembark. Thereafter, the vessel proceeded to Cagayan de Oro City. Petitioner, the next day, boarded the M/V Asia Japan for its voyage to Cagayan de Oro City, likewise a vessel of defendant. On account of this failure of defendant to transport him to the place of destination on November 12, 1991, respondent Arroyo filed before the trial court an action for damage arising from bad faith, breach of contract and from tort, against petitioner. The trial court ruled only for breach of contract. The CA reversed and set aside said decision on appeal. ISSUE: Whether or not the petitioner Trans-Asia was negligent? HELD: Yes. Before commencing the contracted voyage, the petitioner undertook some repairs on the cylinder head of one of the vessels engines. But even before it could finish these repairs, it allowed the vessel to leave the port of origin on only one functioning engine, instead of two. Moreover, even the lone functioning engine was not in perfect condition as sometime after it had run its course, it conked out. This caused the vessel to stop and remain adrift at sea, thus in order to prevent the

ship from capsizing, it had to drop anchor. Plainly, the vessel was unseaworthy even before the voyage began. For a vessel to be seaworthy, it must be adequately equipped for the voyage and manned with a sufficient number of competent officers and crew.[21] The failure of a common carrier to maintain in seaworthy condition its vessel involved in a contract of carriage is a clear breach of is duty prescribed in Article 1755 of the Civil Code. Landingin vs Pantranco, 33 SCRA 284 F: Plaintiffs are parents of 2 girls who were passengers on a Pantranco bus on an excursion trip from Dagupan to Baguio. The bus was open on one side. The TC found that the crossjoint of the bus broke and the bus started to roll back. Some passengers jumped out. The bus driver maneuvered the bus safely to the mountainside. Two of the girls who jumped were seriously injured and died. Held : In Lasam vs Smith, the court held that accidents caused by defects in the automobile are not caso fortuito. The rationale is that the passenger has neither the choice nor control over the carrier in the selection and use of the equipment and appliances in use by the carrier. When the passenger dies or is injured, the presumption is that the CC is at fault or acted negligently. This is only rebutted by proof on the carrier's part that it observed extraordinary diligence required in Art. 1733 and the utmost diligence of very cautious persons required in Art. 1755. It does not appear that the carrier gave due regard for all the circumstances with cross joints' inspection the day previous to the accident. The bus was heavily laden, and it would be traversing mountainous, circuitous and ascending road. Thus the entire bus would naturally be taxed more heavily than it would be under the ordinary circumstances. The mere fact that the bus was inspected only recently and found to be in order would not exempt carrier from liability unless it is shown that the particular circumstances under which the bus would travel were also considered. PRECILLANO NECESITO, ETC. vs. NATIVIDAD PARAS, ET AL. (G.R. No. L-10605, June 30, 1958) FACTS: A mother and her son boarded a passenger auto-truck of the Philippine Rabbit Bus Lines. While entering a wooden bridge, its front wheels swerved to the right, the driver lost control and the truck fell into a breast-deep creek. The mother drowned and the son sustained injuries. These cases involve actions ex contractu against the owners of PRBL filed by the son and the heirs of the mother. Lower Court dismissed the actions, holding that the accident was a fortuitous event. ISSUE: Whether or not the carrier is liable for the manufacturing defect of the steering knuckle, and whether the evidence discloses that in regard thereto the carrier exercised the diligence required by law (Art. 1755, new Civil Code) HELD: Yes. While the carrier is not an insurer of the safety of the passengers, the manufacturer of the defective appliance is considered in law the agent of the carrier, and the good repute

of the manufacturer will not relieve the carrier from liability. The rationale of the carriers liability is the fact that the passengers has no privity with the manufacturer of the defective equipment; hence, he has no remedy against him, while the carrier has. We find that the defect could be detected. The periodical, usual inspection of the steering knuckle did not measure up to the utmost diligence of a very cautious person as far as human care and foresight can provide and therefore the knuckles failure cannot be considered a fortuitous event that exempts the carrier from responsibility. Raynera v. Hiceta| Pardo (G.R. No. 120027) (21 April 1999) FACTS: On March 23, 1989, at about 2:00 in the morning, Reynaldo Raynera was on his way home. He was riding a motorcycle traveling on the southbound lane of East Service Road, Cupang, Muntinlupa. The Isuzu truck was travelling ahead of him at 20 to 30kilometers per hour. The truck was loaded with two (2) metal sheets extended on both sides, two (2) feet on the left and three (3) feet on the right. There were two (2)pairs of red lights, about 35 watts each, on both sides of the metal plates. The asphalt road was not well lighted. At some point on the road, Reynaldo Raynera crashed his motorcycle into the left rear portion of the truck trailer, which was without tail lights. Due to the collision, Reynaldo sustained head injuries and he was rushed to the hospital where he was declared dead on arrival. Edna Raynera, widow of Reynaldo, filed with the RTC a complaint for damages against respondents Hiceta and Orpilla, owner and driver of the Isuzu truck. At the trial, petitioners presented Virgilio Santos. He testified that at about 1:00 and2:00 in the morning of March 23, 1989, he and his wife went to Alabang, market, onboard a tricycle. They passed by the service road going south, and saw a parked truck trailer, with its hood open and without tail lights. They would have bumped the truck but the tricycle driver was quick in avoiding a collision. The place was dark, and the truck had no early warning device to alert passing motorists. Trial court: respondents negligence was the immediate and proximate cause of Rayneras death. CA: The appellate court held that Reynaldo Raynera's bumping into the left rear portion of the truck was the proximate cause or his death, and consequently, absolved respondents from liability. ISSUE & ARGUMENTS (a) whether respondents were negligent, and if so,(b) whether such negligence was the proximate cause of the death of Reynaldo Raynera. HOLDING & RATIO DECIDENDI We find that the direct cause of the accident was the negligence of the victim. Traveling behind the truck, he had the responsibility of avoiding bumping the vehicle in front

of him. He was in control of the situation. His motorcycle was equipped with headlights to enable him to see what was in front of him. He was traversing the service road where the prescribed speed limit was less than that in the highway. Traffic investigator Cpl. Virgilio del Monte testified that two pairs of 50-watts bulbs were on top of the steel plates, which were visible from a distance of 100 meters Virgilio Santos admitted that from the tricycle where he was on board, he saw the truck and its cargo of iron plates from a distance of ten (10) meters. In light of these circumstances, an accident could have been easily avoided, unless the victim had been driving too fast and did not exercise dues care and prudence demanded of him under the circumstances. Virgilio Santos' testimony strengthened respondents' defense that it was the victim who was reckless and negligent in driving his motorcycle at high speed. The tricycle where Santos was on board was not much different from the victim's motorcycle that figured in the accident. Although Santos claimed the tricycle almost bumped into the improperly parked truck, the tricycle driver was able to avoid hitting the truck. It has been said that drivers of vehicles "who bump the rear of another vehicle" are presumed to be "the cause of the accident, unless contradicted by other evidence". The rationale behind the presumption is that the driver of the rear vehicle has full control of the situation as he is in a position to observe the vehicle in front of him. We agree with the Court of Appeals that the responsibility to avoid the collision with the front vehicle lies with the driver of the rear vehicle. Alfredo Mallari, Sr. and Alfredo Mallari, Jr. v. CA and Bulletin Publishing Corp. G.R. No. 128607 January 31, 2000 Bellossillo, J. FACTS: The passenger jeepney driven by Mallari Jr. and owned by Mallari Sr. collided with the delivery van of Bulletin along the National Highway in Brgy. San Pablo, Dinalupihan, Bataan. Mallari Jr. testified that he went to the left lane of the highway and overtook a Fiera which had stopped on the right lane. Before he passed by the Fiera, he saw the van of Bulletin coming from the opposite direction. It was driven by one Felix Angeles. The collision occurred after Mallari Jr. overtook the Fiera while negotiating a curve in the highway. The impact caused the jeepney to turn around and fall on its left side resulting in injuries to its passengers one of whom was Israel Reyes who eventually died due to the gravity of his injuries. Claudia Reyes, the widow of Israel Reyes, filed a complaint for damages against Mallari Sr. and Mallari Jr., and also against Bulletin, its driver Felix Angeles, and the N.V. Netherlands Insurance Co. The complaint alleged that the collision which resulted in the death of Israel was caused by the fault and negligence of both drivers of the passenger jeepney and the Bulletin Isuzu delivery van. ISSUE: WON Mallari Jr. and Mallari Sr. are liable for the death of Israel HELD: Yes. The collision occurred immediately after Mallari Jr. overtook a vehicle in front of it while traversing a curve on the highway. This act of overtaking was in clear violation of Sec. 41, pars. (a) and (b), of RA 4136 as amended,

otherwise known as The Land Transportation and Traffic Code. A driver abandoning his proper lane for the purpose of overtaking another vehicle in an ordinary situation has the duty to see to it that the road is clear and not to proceed if he cannot do so in safety. When a motor vehicle is approaching or rounding a curve, there is special necessity for keeping to the right side of the road and the driver does not have the right to drive on the left hand side relying upon having time to turn to the right if a car approaching from the opposite direction comes into view. Mallari Jr. already saw that the Bulletin delivery van was coming from the opposite direction and failing to consider the speed thereof since it was still dark at 5:00 o'clock in the morning mindlessly occupied the left lane and overtook 2 vehicles in front of it at a curve in the highway. Clearly, the proximate cause of the collision resulting in the death of Israel was the sole negligence of the driver of the passenger jeepney, Mallari Jr., who recklessly operated and drove his jeepney in a lane where overtaking was not allowed by traffic rules. Under Art. 2185 of the Civil Code, unless there is proof to the contrary, it is presumed that a person driving a motor vehicle has been negligent if at the time of the mishap he was violating a traffic regulation. Mallaris failed to present satisfactory evidence to overcome this legal presumption. The negligence and recklessness of the driver of the passenger jeepney is binding against Mallari Sr., who admittedly was the owner of the passenger jeepney engaged as a common carrier, considering the fact that in an action based on contract of carriage, the court need not make an express finding of fault or negligence on the part of the carrier in order to hold it responsible for the payment of damages sought by the passenger. (See Arts. 1755, 1756 and 1759 for the rationale of common carriers liability.)

As far as our digest is concerned

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- LEGT2741 Assignment (Week 5)Document9 pagesLEGT2741 Assignment (Week 5)Danny NgNo ratings yet

- Case LC105556 - YEHUDA NETANEL VS WINGS OF RESCUE PDFDocument3 pagesCase LC105556 - YEHUDA NETANEL VS WINGS OF RESCUE PDFJames SmithNo ratings yet

- Carriage by Road ActDocument22 pagesCarriage by Road ActPRADEEP MK100% (1)

- CasesDocument12 pagesCasesGoliath BirdeaterNo ratings yet

- PrecedentialDocument41 pagesPrecedentialScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Agency DigestsDocument12 pagesAgency DigestsBobby Olavides SebastianNo ratings yet

- Mindanao Shopping Destination v. DuterteDocument16 pagesMindanao Shopping Destination v. DuterteDevilleres Eliza DenNo ratings yet

- Applying For A Passport From Outside The UK: Helping You Fill in The Application FormDocument18 pagesApplying For A Passport From Outside The UK: Helping You Fill in The Application Formtabish_khattakNo ratings yet

- Pioneer Insurance Vs APL Aug 2 2017Document1 pagePioneer Insurance Vs APL Aug 2 2017Alvin-Evelyn GuloyNo ratings yet

- 18 Mary Elizabeth Ty Delgado v. HRETDocument2 pages18 Mary Elizabeth Ty Delgado v. HRETIgi Filoteo100% (3)

- (DAILY CALLER OBTAINED) - American Airlines LetterDocument2 pages(DAILY CALLER OBTAINED) - American Airlines LetterHenry RodgersNo ratings yet

- Pilar Pagsibigan vs. Court of AppealsDocument6 pagesPilar Pagsibigan vs. Court of AppealsFairyssa Bianca SagotNo ratings yet

- United States v. Keith Gordon Ham, A/K/A Number One, A/K/A K Swami, A/K/A Kirtanananda, A/K/A Srila Bhaktipada, A/k/a/ Kirtanananda Swami Bhaktipada, United States of America v. Steven Fitzpatrick, A/K/A Sundarakara, United States of America v. Terry Sheldon, A/K/A Mr. Scam, A/K/A Tapahpunja, 998 F.2d 1247, 4th Cir. (1993)Document13 pagesUnited States v. Keith Gordon Ham, A/K/A Number One, A/K/A K Swami, A/K/A Kirtanananda, A/K/A Srila Bhaktipada, A/k/a/ Kirtanananda Swami Bhaktipada, United States of America v. Steven Fitzpatrick, A/K/A Sundarakara, United States of America v. Terry Sheldon, A/K/A Mr. Scam, A/K/A Tapahpunja, 998 F.2d 1247, 4th Cir. (1993)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Recent Developments in German Succession Law: Thomas RauscherDocument14 pagesRecent Developments in German Succession Law: Thomas RauscherfelamendoNo ratings yet

- 12 Republic V OrtigasDocument16 pages12 Republic V OrtigasJm CruzNo ratings yet

- De Silva Vs AboitizDocument5 pagesDe Silva Vs AboitizNivla YacadadNo ratings yet

- Irs Letter 2 - Internal Revenue Service - Notary PublicDocument21 pagesIrs Letter 2 - Internal Revenue Service - Notary PublicAQUA KENYATTENo ratings yet

- Consent To PublishDocument3 pagesConsent To PublishAhmed MansourNo ratings yet

- Case Note 2019 - Swift V Secretary of State For Justice (2013)Document3 pagesCase Note 2019 - Swift V Secretary of State For Justice (2013)ماتو اریکاNo ratings yet

- Conrad Fromme DeclarationDocument119 pagesConrad Fromme DeclarationRobbie .PowelsonNo ratings yet

- Lattimore v. Polaroid Corp., 1st Cir. (1996)Document70 pagesLattimore v. Polaroid Corp., 1st Cir. (1996)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- AAP Vs LG: Full Text of Supreme Court JudgmentDocument535 pagesAAP Vs LG: Full Text of Supreme Court JudgmentThe Indian ExpressNo ratings yet

- Minutes of MeetingDocument4 pagesMinutes of MeetingNatalie Abaño100% (1)

- Succession CodalDocument17 pagesSuccession CodalEllyssa Timones100% (1)

- Tapan Kumar SinghDocument10 pagesTapan Kumar SinghHARSHIL SHRIWASNo ratings yet

- Mary Catherine Hilario Atty. Carlo Edison Alba Public Prosecutor Counsel For The AccusedDocument4 pagesMary Catherine Hilario Atty. Carlo Edison Alba Public Prosecutor Counsel For The AccusedChaddzky BonifacioNo ratings yet

- Cojuangco, Jr. v. PCGG, G.R. Nos. 92319-20, October 2, 1990, 190 SCRA 226, 243Document2 pagesCojuangco, Jr. v. PCGG, G.R. Nos. 92319-20, October 2, 1990, 190 SCRA 226, 243Emil Bautista100% (2)

- Republic of The Philippines Court of Tax Appeals Quezon City Second DivisionDocument10 pagesRepublic of The Philippines Court of Tax Appeals Quezon City Second DivisionPaulNo ratings yet

- Motion To Reconsider 3 14 FinalDocument14 pagesMotion To Reconsider 3 14 FinalJamil B. AsumNo ratings yet

- Amendments To SOLAS Regulation II-1-3-8Document3 pagesAmendments To SOLAS Regulation II-1-3-8jimmyNo ratings yet