Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Power of The Small SEIDELMAN

Uploaded by

Martyna Weronika KunaOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Power of The Small SEIDELMAN

Uploaded by

Martyna Weronika KunaCopyright:

Available Formats

The Power of the Small: The Impact of Ethnic Minorities on Foreign Policy Stephen M.

Saideman Abstract: Ethnic minorities often have a greater impact on the government's foreign policy than their size may otherwise lead to believe. Before considering to what extent ethnic groups influence foreign policymaking, it is important to understand their interestswhat ethnic identities may imply for external relations. In this regard, minorities face a variety of constraints, including repression, failure to mobilize, and a focus on domestic politics. However, ethnic minorities also possess some unique advantages. They may find it easier to organize by virtue of their small size; they are often more focused on a narrow set of issues; and they frequently face less opposition from majority groups on these particular issues. Ethnic groups have resorted to a variety of strategies to influence their state's foreign policies, which have implications for policymaking in general.

Numbers imply strength, or that is the usual assumption. How ever, ethnic minorities, despite smaller numbers and in some cases political repression, can play a significant role in influencing a country's foreign policy. In many cases, smaller groups may in fact exert a disproportionately large influence, sometimes greater than that exhibited by the majorities or pluralities with which they coexist. Even in cases where the majority clearly drives foreign policy, the fact that minority groups exert less influence relative to majority groups certainly does not mean they have no influence. Despite certain constraints, minorities can indeed shape the foreign policy of many countries; a good starting point in analyzing [End Page 93] their relative preponderance in policymaking is to examine the factors and strategies that either limit or increase their influence.

First, why should we expect ethnic minorities to have little or no influence on foreign policy?One constraint is a simple lack of political mobilization. A minority group may not be sufficiently mobilized politicallyto influence government policy, domestic or foreign. Another crucial constraint is repression. Additionally, even when a minority group is mobilized and wields some political power, it may have little interest in foreign policy or be solely preoccupied with domestic issues. Those ethnic groups that do focus on foreign policy may not be the only ones interested in the issue and are likely to face competition from rival groups also seeking to shape a particular policy.

Second, for those minority groups who do wield some measure of political power, they must determine what they want their host state to do in the international arena. In order to assess their influence, we need to understand the preferences of minority ethnic groups, considering both economic and "ethnic" interests.

Third, can "active" minorities influence foreign policy? In fact, minorities actually have several advantages that make it not only possible, but even likely for them to be able to shape foreign policy. These advantages include the relative ease of organizing smaller groups, their narrower focus on a limited set of issues, and, frequently, apathetic majorities that have no obvious stake in the particular set of issues espoused by the ethnic group.

Smaller groups may choose different strategies to sway policymakers, depending on the political environment within which they exist. In democracies, minorities may exert influence because they are able to deliver votes in key constituencies; they serve as the source of campaign contributions; they are the basis for ethnically based parties that serve as necessary coalition partners; they shape the agendas of the media and public institutions; and they can develop their own foreign policies via their direct, often financial, support of kin abroad. In authoritarian regimes, a group's ability to influence policymaking will depend on its role within the government and whether the group has its own resources upon which it can draw. Ethnic Groups are Interest GroupsInterested in Identity

If we want to know how ethnic minorities might influence foreign policy, we must consider what they are trying to do. 1 That is, what [End Page 94] do ethnic groups want? What kinds of policies do they seek to influence, and what changes do they wish to implement? Individuals within any ethnic group will care about a great many things, but what they have in common, their identities, will influence their common preferences. 2 While identity can refer to many things, in this context, we focus on what makes a group a minority in the conventional senseits religion, language, race, nationality, or clan or tribal affiliations. Domestically, a minority's concerns will largely focus on how the government treats the group's members, including how laws affect the group's religious practice, whether the government privileges the speakers of other languages, whether policies treat members of one race or clan differently than others, and the like.

In foreign policy, an ethnic group may care about economic policy insofar as economic flows influence the status and welfare of the group. But, individual members of a minority are likely to be affected differently by international economic dynamics. Indeed, since some members may benefit from increased international trade while others may find this detrimental, not all members of the ethnic group will necessarily share the same economic positions or interests. Therefore, we generally do not consider ethnic groups interested in foreign economic policy.

Instead, an ethnic group's communal concerns are more likely to focus on the plight of those in other countries with whom the group's members identify. Members of a group will identify with other members regardless of whether they reside on the same side of a border or not. Catholics will

identify with their religious brethren in other states, as was the case when Austria and Italy supported Croatia in its conflict against Serbia. Religion played a central role in the disintegration of Yugoslavia, influencing outsiders' reactions to the conflict. Just as Catholics were concerned with the plight of the Croats, Orthodox nations tended to support the Serbs, and Muslims wanted their states to support Bosnia against the other two. 3 African-Americans in the United States cared about the plight of the blacks in South Africa during apartheid. 4 Finding the oppression of the black majority to be offensive, African-Americans mobilized to seek sanctions against South Africa. In comparison, African-Americans have not wielded similar power in international economic relations.

As recent events in Afghanistan illustrate, Uzbeks in Uzbekistan care about what happens to Uzbeks across the border. Tajiks, Turkmen, and Pashtuns also care about members of their [End Page 95] groups in war-torn Afghanistan. Despite its own economic limitations, Uzbekistan has given significant support over the past few years to the Uzbeks of Afghanistan. Similarly, Tajikistan, despite or because of its own political instability, remained involved in Afghanistan's domestic politics, supporting its Tajik population. 5

These examples are suggestive, and research in the field of the international relations of ethnic conflict provides ample evidence that ethnic groups care about their kin in other states, and that they are often able to influence the foreign policy of their host country. These studies have shown that ethnic affinities, by definition, are instrumental in irredentist crises; 6 in addition, they determine the level of support given to ethnic groups, particularly secessionist groups, and they even increase the likelihood of war. 7 However, most of this work considers the impact of ethnic majorities influencing foreign policy toward a country in which their kin are in danger, not the impact of minorities. Therefore, while the implications of these studies are suggestive, the initial question remains: do ethnic minorities influence foreign policy, and, if so, how? Size Has Its Disadvantages

Ethnic minorities face at least three main constraints in influencing foreign policy. First, a minority may have difficulty mobilizing politically. Minority groups may be the target of repressive government policies and repressed groups are unlikely to be able to influence their host state's foreign policies. 8 Repression can occur in both democracies and authoritarian regimes, though the latter tend to be more repressive. In either case, a group facing repression at home will be more focused on their domestic dilemma than on the plight of groups elsewhere, except for the pursuit of external support. Further, because they have fewer resources, members of the group will have a harder time lobbying politicians. Moreover, they may not be able to organize openly, nor promote and advertise their cause. Indeed, it may be considered anathema for a politician to meet with a repressed group.

In my efforts to understand the relationships between ethnic ties and the international relations of ethnic conflict, I performed quantitative analyses that showed that ethnic groups that neighbored a state where their kin dominated received more support than other groups. 9 At the same time, I performed similar analyses (that I have not yet formally presented), which substituted [End Page 96] Roma (commonly known as gypsies), a very seriously repressed group, for groups with dominant kin in neighboring countries. Roma were much less likely to receive support, and I inferred that it was because their kin, Roma in other states, were also a minority group and had little or no influence over the policies of their host states. Since the Romaminorities in every country where they resideare not only often severely repressed, but also tend to be poor and insufficiently organized, their ability to influence foreign policy is extremely limited. Still, their case is suggestive. Groups in very weak political positions, as the result of repression or other limitations, will not influence foreign policy.

Second, an ethnic group may frequently encounter competition from other ethnic groups. Serbs in the United States, Canada, and elsewhere sought policies friendlier to Bosnian Serbs and to Serbia, but failed miserably, as these countries opposed Bosnian Serb efforts to create a separate state or unite with Serbia. The Serb diaspora, in trying to advance the cause of their home country, faced competition in a variety of countries from lobbyists representing the Croatian diaspora and Muslims. As a result, they were not able to define the issues in a way that could entice Western governments to intervene in favor of Serb objectives. One could argue that the impact of any of these groups was largely balanced by the influence of its competitors, leaving leaders freer to pursue other interests, including regional security and efforts to support multilateral institutions.

Similarly, members of Turkish groups are frequently frustrated as they compete with Greeks for influence in North America and western Europe. Turks have sought increased support for Turkey in the country's bid to enter the European Union and in its disputes with Greece. However, Greeks in a variety of countries, including the United States, have better organizations and political access, limiting the ability of Turks to influence foreign policy. Ethnic identity is one cleavage that determines group membership, and if two competing ethnic groups are mobilized within the same political community, they may undermine each other's ability to influence foreign policy. [End Page 97]

Third, while smaller groups may be able to organize better and focus on specific issues, their narrow focus may make it harder for them to work in broader coalitions. Such groups may not be willing to make tradeoffs to gain support or agree to compromises if they have no other interests at stake. In addition, they may not have much to offer in terms of logrolling to create larger coalitions with other groups since they focus on a limited set of issues. Smaller is Better

At first blush, it might appear that ethnic minorities have little influence on foreign policy due to their small size. However, for at least thirty years, it has been conventional wisdom in political science and economics that smaller groups have a variety of advantages in organizing and advancing their interests. Mancur Olson argued that the difficulties inherent in organization make it hard for larger groups, as they cannot determine who contributes to the welfare of the group and who free rides on the efforts of others. 10 Smaller groups, particularly ethnic minorities, can more easily police themselves, making sure that members contribute to the cooperative effort and that those who do not are punished. 11 Thus, ethnic minorities may actually be more effective than ethnic majorities in gathering resources, mobilizing, developing coherent organizations, lobbying politicians, and facilitating protests (or organizing rebellion).

A second advantage is that smaller groups will tend to have a narrower focus, while larger groups will have interests in a variety of issues. For example, a minority ethnic group may concentrate exclusively on its plight and the plight of its kin elsewhere, whereas the remainder of the society may have a variety of concerns at any one time. The mismatch of focused interest and diffuse concerns means that an ethnic minority may be able to shape foreign policy simply because opponents may be distracted or because, as is often the case, there is no opposition to speak of.

The case of Greek-Americans and their impact on U.S. policy in the Balkans provides an excellent example of this dynamic playing out in favor of an ethnic minority. In the early 1990s, the majority of Americans probably could not locate Macedonia on a map. Meanwhile, Greek-Americans were pushing strongly for policies limiting U.S. engagement with Macedonia, to the point that the United States still recognizes the country as the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia rather than the Republic of Macedonia, its [End Page 98] official name since independence (which Greece did not initially recognize). More importantly, the United States did not stop Greece's blockade of Macedonia after it became independent. This weakened Macedonia's economy, reducing its ability to handle its own ethnic conflict. U.S. policy was counterproductive to U.S. interests, as instability in Macedonia threatened to spreadand recently has. Politicians dependent upon Greek-American votes and campaign contributions, such as Senator Paul Sarbanes of Maryland, worked tirelessly to protect the group's interests, including trying to pass laws that would prohibit closer relations between the United States and Macedonia.

Ethnic minorities have a third advantage in that they may care about particular foreign policy issues that are largely irrelevant to the overwhelming majority of their country's society. Diasporas working for the benefit of their kin in other countries can gain disproportionate influence over their government's policies toward those countries precisely because of public apathy as well as ignorance on the part of majority groups.

Again, using the U.S. case as an example, Armenian-Americans have been quite effective in limiting U.S. interaction with Azerbaijan. War between Armenia and Azerbaijan over Azerbaijan's Nagorno-

Karabakh territory, largely inhabited by Armenians, coincided with the end of the Soviet Union. In a rare case of successful irredentism, Armenia has been able to annex the contested territory along with land connecting Armenia to Nagorno-Karabakh. In a law aimed at assisting Russia in its transition, Armenian-Americans were able to include language restricting U.S. support of Azerbaijan. Indeed, the controversial section 907 of the Freedom Support Act of 1992 explicitly banned U.S. assistance to Azerbaijan. The president had to "report to the Congress, that the Government of Azerbaijan is taking demonstrable steps to cease all blockades [which were a product of the war] and other offensive uses of force against Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh." 12 This is rather striking, as it essentially means that the United States would ban assistance to a country that, in many ways, was resisting ethnically motivated aggression. Because Armenian-Americans have focused on this issue, politicians seeking their votes have cared a great deal more about Armenia and have taken up the country's cause. 13 Despite President Clinton's opposition to it, Section 907 remained unassailable throughout the 1990s; it was only recently waived, reflecting Azerbaijan's newfound strategic value in the aftermath of September 11. Most Americans are completely [End Page 99] unaware of the Armenian-Azeri conflict, and Section 907 was only of interest to Armenia, Azerbaijan, and the Armenian diaspora in the United States. Armenian-Americans' successful lobbying efforts illustrate how majority apathy can permit smaller and more motivated groups to effectively shape foreign policy.

The advantages accruing to ethnic minorities are often overlooked. While the situations they face may sometimes limit their ability to significantly influence foreign policy, creative leaders and coherent groups can make a difference while divided, rudderless groups may be unable to help their kin abroad. Strategies of the Small

There are a variety of tools available to minorities as they seek to affect their state's foreign policy. Which strategies minority groups will adopt depends on a number of key characteristics of the society in which they live. The nature of the regime in the host state will influence which strategies a group chooses. Regime type matters, as particular avenues of influence are more likely to be effective, or to exist at all, in a democracy, while authoritarian politics are likely to disadvantage a minority groupexcept in a limited number of cases when certain conditions exist. Specifically, voting, campaign contributions, and party as well as coalition strategies are all potentially powerful tools for shaping foreign policy in democracies, methods that are unavailable to groups under authoritarian rule. In a democracy, groups voting as a bloc will have more power than those that do not. As mentioned above, ethnic minorities are likely to focus on a limited set of foreign policy issues, in addition to their domestic agenda. However, a group's smaller size may limit its impact on elections, unless its members are concentrated in important districts. Cuban-Americans, for example, largely determine U.S. foreign policy toward Cuba because of their electoral strength in Florida, a key swing state. 14 Therefore, to assess a minority group's ability to influence foreign policy, a key question to ask is whether its members are geographically concentrated, and, if so, where they are located. [End Page 100]

Concentration does not necessarily mean as much in countries where the electoral system permits the development of multiple parties. If ethnic groups are large enough to form their own parties, and if the electoral system does not require concentration to gain seats (for instance, in many systems with proportional representation), then an ethnic party may be able to win enough votes to gain seats in the legislature. If this occurs, the minority will be able to shape foreign policy, and this influence can be quite powerful. Such a party may act as a necessary coalition partner, earning the prerogative to articulate its foreign policy preferences as a key reward for its participation in government. Israel is an obvious example, where smaller, ethnically-based parties can do quite well under the rules of its electoral system. Religious parties as well as those representing Arabs have been able to achieve political representation and play key roles in coalitions. Even if the party is not included in government, occupying seats in the legislature increases the group's ability not only to place its issues on the legislative agenda, but also to bring them to the media's attention.

Besides voting and representation, another key element in modern democracies is campaign finance. Groups contributing money to politicians can gain political access, sometimes even in the form of political appointments. Politicians frequently meet with those giving significant amounts of campaign contributions. While donations do not equal votes, there is a positive relationship between the two. Furthermore, winning parties often nominate those individuals that helped finance the campaign to significant posts, including positions in foreign policy bureaucracies.

In authoritarian regimes, the group's role within the government is the key determinant of political influence. The most important positions to occupy are those that control the means of coercion. A ruler in a nondemocratic system needs the loyalty of the military, the police (secret or otherwise), and, if one exists, the presidential guard. Regime change in such systems usually turns on the loyalties of those who carry the guns. Protests can be put down if the military and the police are willing to use violence, as was the case at Tiananmen Square in 1989. However, if the military decides to change sides, then the incumbents will fall, and those who lose office may also lose their lives. Therefore, rulers in such systems will not only monitor the key coercive institutions, but also try to buy them off by giving them money and supporting their positions. [End Page 101]

Take the case of authoritarian Somalia in the 1970s. Somalia was perceived to be an incorrigibly irredentist state, seeking to unite the Somali-inhabited territories of Djibouti, Ethiopia, and Kenya into a Greater Somalia. 15 At the outset of the military regime, the new rulers sought to cooperate with neighboring states and reduced support for groups in these countries that sought to unite with Somalia. However, Siyad Barre, the country's dictator, became increasingly dependent on three clans for his position: his own, the Marehan, which was the only clan to staff the presidential guard; his son-in-law's, the Dolbohanta, which dominated the secret police, and his mother's, the Ogaden, who were overrepresented in the officer corps of the army. This is important, as many members of the Ogaden clan reside in the eastern region of Ethiopia bearing the same name. As Barre's dependence

on this clan grew, its members increasingly lobbied for aggressive actions to be taken on behalf of its kin. This ultimately led to the war with Ethiopia in 1977-78, which not only resulted in Somalia's defeat, but also contributed to the end of Somalia as a functioning state.

What is important here is that the irredentist efforts were made on behalf of a single clan within a single clan family. The rest of Somalia was not as enthusiastic as one might have expected, given the shared religious, linguistic, racial, and national ties. However, as is clear today, what mattered then and what matters today in Somalia are not the broader shared attributes, but the politics of clan affiliation. 16 In sum, because of its key position within an authoritarian system, a minority was able to push the country to war, ultimately leading to self-destruction.

Strategies are available in any kind of political system, including agenda setting, corruption, and the development of substate foreign policy. First, a group can increase the salience of an issue on the national foreign policy agenda through publicity and activism. Groups can use the media and the national institutions, such as the courts or the legislature,not only to define the issues but also to portray their cause in favorable terms. If an ethnic conflict elsewhere can be defined as a fight against injustice, then there [End Page 102] may be more support for doing something about it. For instance, activists of African descent in Europe and North America were able to define apartheid as unjust and to mobilize other groups in their countries, forcing their governments to alter their foreign policies toward South Africa.

Second, corruption is an important, though often ignored, means of influencing the behavior of politicians. A group may be able to rent key politicians via bribes. While corruption typically comes into play for domestic issues, such as the allocation of the national budget, a motivated group may just as easily get a key politician or bureaucrat to pursue a favorable course of action in foreign policy through bribes or other corrupt practices. For instance, President Abbe Fulbert Youlou of CongoBrazzaville shaped his foreign policy toward the crisis in neighboring Congo (formerly Zaire) based on generous financial support he received from abroad to buy off ethnic interest groups at home. 17

Third, a group may develop its own subnational foreign policy, independently of its government. Groups can provide funds, arms, and even personnel to help its kin elsewhere. While Albania provided much support to the Kosovo Liberation Army, Albanians in other parts of the world provided much of the money, equipment, and soldiers in the fight against Serbia, and, subsequently, in the conflict in Macedonia. Likewise, Tamils in India and Canada have played an important role in helping Tamil secessionists in Sri Lanka fight the island's government for nearly twenty years. This is not a new phenomenon, but deserves more attention, as the power of diasporas increases compared to that of many states at war with the diasporas' respective kin.

Obviously, groups can rely on more than one strategyboth influencing their home state and trying to change the situation on the ground with their own foreign policies. There may be tradeoffs between various strategies, as efforts to engage in foreign policy may offend or upset politicians and thereby reduce the group's political influence. There are a variety of strategies, but their availability and effectiveness depend on the specific political context within which the minority group works. [End Page 103] Policy Implications

From a policy standpoint, what is the relevance of the relationship between ethnic groups and political power? First, by understanding the roles minorities can play in foreign policy, we can better predict what other states are likely to do. By knowing under what conditions smaller groups have influence, we are less likely to be surprised when countries are less united than expected, and when smaller groups triumph in policy debates. Better predictions make for better policy. Second, understanding these dynamics should enable minorities to exert more influence. 18 While many groups may intuitively understand their capabilities, having a clearer idea of their limitations and their advantages might improve their ability to exert influence. Further, politicians seeking allies in policy debates ought to consider smaller groups as potentially powerful coalition partners, rather than ignoring them.

In conclusion, taking minorities and their impact upon foreign policy seriously would be a smart move. Governments must recognize the importance of ethnic minorities as powerful substate actors if they are to deal effectively with the governments who areinfluenced by them,and if they are to develop sound foreign policy in regions, which attract the attention of vocal diasporas active domestically.

Stephen M. Saideman is currently working on the Bosnia desk of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Strategic Planning and Policy Directorate as a Council on Foreign Relations International Affairs Fellow. Next fall, he will be an Associate Professor of Political Science at McGill University. The views contained in this article do not necessarily reflect those of the Defense Department or those of the Council. Notes

1. For a discussion of the nature of ethnic identity, see Will Moore's contribution to this volume.

2. For a discussion of identities influencing foreign policy, see Michael Barnett and Shibley Telhami, eds., Communal Identity and Foreign Policy in the Middle East (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2001).

3. Stephen M. Saideman, The Ties That Divide: Ethnic Politics, Foreign Policy, and International Conflict (New York: Columbia University Press, 2001).

4. D.R. Calverson, "The Politics of the Anti-Apartheid Movement in the United States, 1969-1986," Political Science Quarterly (spring 1996): 127-149.

5. For discussions of Tajik influence on Uzbekistan's foreign policy, see Richard Foltz, "The Tajiks of Uzbekistan," Central Asian Survey 15, no. 2 (June 1996): 213-217. For the Uzbek influence on Tajikistan's foreign behavior, see Stuart Horseman, "Uzbekistan's Involvement in Tajikistan's Civil War, 1992-1997: Domestic Considerations," Central Asian Survey 16, no. 1 (March 1999): 37-48.

6. David Carment and Patrick James, "Internal Constraints and Interstate Ethnic Conflict: Toward a Crisis-Based Assessment of Irredentism," Journal of Conflict Resolution 39 (1995): 82-109.

7. For a discussion of ethnic support to secessionist movements, see Stephen M. Saideman, "Discrimination in International Relations: Examining Why Some Ethnic Groups Receive More External Support Than Others," Journal of Peace Research (January 2002): 27-50; the link between ethnic politics and armed conflict is dealt with in David R. Davis and Will H. Moore, "Ethnicity Matters: Transnational Ethnic Alliances and Foreign Behavior," International Studies Quarterly (1997): 171-184.

8. Christian Davenport's work serves as an excellent introduction to the state-of-the-art research into repression, particularly "Constitutional Promises and Repressive Reality: A Cross-National Time-Series Investigation," Journal of Politics (1996): 627-654. See also Will Moore, "The Repression of Dissent: A Substitution Model of Government Coercion," Journal of Conflict Resolution (February 2000): 107127.

9. Saideman, The Ties That Divide, chapter six.

10. Mancur Olson, The Logic of Collective Action: Public Goods and the Theory of Groups (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1965).

11. For a discussion of policing within groups, see James D. Fearon and David D. Laitin, "Explaining Interethnic Cooperation," American Political Science Review (December 1996): 715-735.

12. U.S. Public Law 102-511, cited in David King and Miles Pomper, "Congress, Constituencies, and US Foreign Policy in the Caspian" (paper prepared for the conference "Culture and Foreign Policy," Harvard Caspian Studies Program, January 30-February 1, 2001).

13. See Kind and Pomper, "Congress, Constituencies, and US Foreign Policy in the Caspian," for evidence of the connections between the Armenian diaspora, politicians' electoral interests, and Section 907.

14. Patrick J. Haney and W. Vanderbush, "The Role of Ethnic Interest Groups in US Foreign Policy: The Case of the Cuban American National Foundation," International Studies Quarterly (June 1999): 341361.

15. For more on Somalia's irredentism, see Stephen M. Saideman, "Inconsistent Irredentism? Political Competition, Ethnic Ties, and the Foreign Policies of Somalia and Serbia," Security Studies 7, no. 3 (spring 1998): 51-93.

16. David D. Laitin and Said S. Samatar, Somalia: Nation in Search of a State (Boulder: Westview Press, 1987).

17. Saideman, Ties That Divide, chapter three.

18. Whether this is good or bad is an important question that has been raised by others. See Tony Smith, Foreign Attachments: The Power of Ethnic Groups in the Making of American Foreign Policy (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000); and Yossi Shain, Marketing the American Creed Abroad: Diasporas in the U.S. and Their Homelands (Cambridge: Cambrige University Press, 2001).

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The World War DeceptionDocument456 pagesThe World War Deceptionupriver86% (36)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

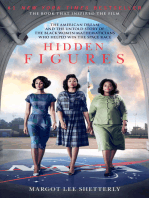

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Why William Wordsworth Called As A Poet of NatureDocument12 pagesWhy William Wordsworth Called As A Poet of NatureHạnh Nguyễn80% (10)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Autonomous Learner Model SampleDocument21 pagesAutonomous Learner Model Sampleapi-217676054100% (1)

- Writing Term 3 Fairy Tales-NarrativesDocument6 pagesWriting Term 3 Fairy Tales-Narrativesapi-364740483No ratings yet

- The Unconscious Before Freud by Lancelot Law WhyteDocument213 pagesThe Unconscious Before Freud by Lancelot Law WhyteMyron100% (2)

- Spitzer y Auerbach PDFDocument197 pagesSpitzer y Auerbach PDFDiego Shien100% (1)

- Field TheoryDocument2 pagesField TheoryMuhammad Usman100% (5)

- 2nd Periodic Test English Tos BuhatanDocument3 pages2nd Periodic Test English Tos BuhatanMarlynAzurinNo ratings yet

- Theories of JournalismDocument7 pagesTheories of JournalismWaqas MahmoodNo ratings yet

- Jane Sansom: Firewalking: Explanation and The Mind-Body Relationship'Document15 pagesJane Sansom: Firewalking: Explanation and The Mind-Body Relationship'Guillermo SaldanaNo ratings yet

- Problems and Prospects in ManuscriptsDocument6 pagesProblems and Prospects in ManuscriptsDr. JSR PrasadNo ratings yet

- Mansfield Park (Analysis of Mrs Norris)Document2 pagesMansfield Park (Analysis of Mrs Norris)kyra5100% (1)

- Mosaic TRD3 Extrapractice U1 PDFDocument4 pagesMosaic TRD3 Extrapractice U1 PDFRita morilozNo ratings yet

- Patrick GeddesDocument13 pagesPatrick GeddesShívã Dúrgèsh SDNo ratings yet

- Rectilinear Tall Structure Design PlateDocument2 pagesRectilinear Tall Structure Design PlateYna MaulionNo ratings yet

- Worksheet TemplateDocument2 pagesWorksheet TemplateNise DinglasanNo ratings yet

- My Grandfather's Life JourneyDocument3 pagesMy Grandfather's Life JourneySwaraj PandaNo ratings yet

- International Relations PDFDocument65 pagesInternational Relations PDFJasiz Philipe OmbuguNo ratings yet

- Role of Digital MarketingDocument2 pagesRole of Digital MarketingZarish IlyasNo ratings yet

- Lawrence Kohlberg - American Psychologist - BritannicaDocument6 pagesLawrence Kohlberg - American Psychologist - BritannicaJoanne Balguna Y ReyesNo ratings yet

- Caste in IndiaDocument32 pagesCaste in Indiapatel13005No ratings yet

- Task 1 - Pre-Knowledge TestDocument6 pagesTask 1 - Pre-Knowledge TestYeimmy Julieth Cardenas MillanNo ratings yet

- Agree & Disagree - Technology-N10: Writing Task 2Document2 pagesAgree & Disagree - Technology-N10: Writing Task 2Quang HuyNo ratings yet

- Bioart: ReviewDocument11 pagesBioart: ReviewPavla00No ratings yet

- ArtikelDocument15 pagesArtikelIna QueenNo ratings yet

- QR Code Money ActivityDocument4 pagesQR Code Money Activityapi-244087794No ratings yet

- The Relationship Between Democracy Women Participation in PoliticsDocument10 pagesThe Relationship Between Democracy Women Participation in PoliticsBorolapoNo ratings yet

- Salvador DaliDocument5 pagesSalvador Daliკონჯარია საბაNo ratings yet

- Fashion Design in Prod Dev Using Telestia AB Tech-Dr Nor SaadahDocument9 pagesFashion Design in Prod Dev Using Telestia AB Tech-Dr Nor SaadahNick Hamasholdin AhmadNo ratings yet

- Grade 6 DLL MAPEH Q4 Week 3Document2 pagesGrade 6 DLL MAPEH Q4 Week 3rudy erebiasNo ratings yet