Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Seminar Beik

Uploaded by

Seung Joo BeikOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Seminar Beik

Uploaded by

Seung Joo BeikCopyright:

Available Formats

Seung Joo, Beik

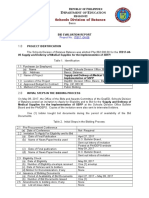

Internet and Computer Crime Seminar

Prof. Joseph v. Demarco

Criminal Liability of P2P Service Provider for Individual Users Copyright Infringement Why not?

I. Introduction

The advent of the Internet has enabled individuals to duplicate and distribute widely perfect copies of music, movies, and other creative content. 1 New digital technologies have enabled anyone with a few minutes of time to share copyrighted songs or videos. These technologies to engage easily in mass copying and distribution have threatened the traditional economic model of copyright protection.2 Recently, P2P technology consequently has forced a seismic shift in copyright enforcement.3 Content owners enforce their rights by suing direct infringers as well as by suing facilitators.4 This is because lawsuits against individuals have proven far less effective when the costs of copying and distribution are nominal, 5 and the infringers are millions of nearly anonymous individuals.6 Such shift has resulted in some high-profile civil lawsuits against P2P service providers: Napster, Aimster, KaZaA, Morpheus, and Grokster. However, still dormant are criminal liability provisions against P2P service providers. Instead, prosecutors have charged a large number of infringers. Are the individual infringers are correct targets?7 For recent ten years, despite civil actions against P2P service providers or prosecutions against individual infringers, one thing is certain: file-sharing technologies have not

1

See Mark A. Lemley & R. Anthony Reese, Reducing Digital Copyright Infringement Without Restricting Innovation, 56 Stan. L. Rev. 1345, 1374-75 (2004).

2

It is uncontroversial that unauthorized digital copying and distribution threaten the economic viability of current media publishers and distributors. See, e.g., Peter K. Yu, P2P and the Future of Private Copying, 76 U. Colo. L. Rev. 653, 746 (2005) (Computers, digital technology, and file-sharing networks are disrupting the existing distribution model, threatening to permanently eliminate hundreds of thousands of jobs.); see also June M. Besek, Anti-Circumvention Laws and Copyright: A Report from the Kernochan Center for Law, Media, and the Arts, 27 Colum. J.L. & Arts 385, 487 (2004) (discussing remedies for digital piracy, which threatens traditional distribution models).

3

Lemley & Reese, supra at 1353. Id. at 1354.

4

5

See Raymond Shih Ray Ku, The Creative Destruction of Copyright: Napster and the New Economics of Digital Technology, 69 U. Chi. L. Rev. 263, 273-74, 300 (2002) (noting that [o]nce a work is created, the marginal cost of making an unlimited number of digital copies and distributing them worldwide is zero, and that potential for distributing music and the reduced costs of copying represent the dark side of digital technology for copyright holders).

6

Compare Lemley & Reese, supra at 1349 (noting low return to suing any one individual when population of direct infringers is very large), and Dogan, supra at 76 (The advent of file-sharing technologies has decentralized the distribution process, making it daunting to identify and take action against individual infringers.), with id. at 80 (arguing that direct infringement suits against primary infringers--i.e., those who actually copy and benefit from copyrighted works--may well deter enough unauthorized file-sharing to stanch the current flood of infringement).

7

See Orin S. Kerr, Computer Crime Law American Casebook Series, West (Second Ed. , 2009) at 161.

Seung Joo, Beik

Internet and Computer Crime Seminar

Prof. Joseph v. Demarco

disappeared.8 This Note explores and explains the possibility of criminal prosecution of Peer-to-Peer (P2P ) service providers. There has been no case dealing with this matter. Even though these P2P technologies have been generated civil lawsuits against the owners and creators of the technologies,10 they have not led to criminal indictments. Why not? We have statute and clear precedents. For this argument, this Note will show there is no barrier for criminal sanction. Before the argument, it is necessary to review a quick background of P2P.

9

II.

P2P Service Providers Liability for Users Copyright Infringement

1. Brief Review on the Mechanism of P2P11 The basic premise of P2P networks is to allow people who want to share files on their computer to freely connect with other person of like mind. Every computer in a file-sharing network can be both a client and a server, and the methods for connecting them together into one huge network are all handled by the file-sharing software.12 In other words, there is no server needed for peer-to-peer file sharing.13 In a P2P system, the information is not stored on a centralized server; rather, it is distributed among many computers that act simultaneously as both clients and servers.14 For example, Gnutella, Kazaa, Morpheus, Limewire, or eMule with Kademlia, allow those who download the free software to use it for copying the copyrighted files through the computers of other users, which threatened the music and video industry. 2. Exploring Three Major Cases against P2P Service Provider

8 9 10

See also Bryan H. Choi, The Grokster Dead-End, 19 Harv. J.L. & Tech. 393, 394 (2006). Hereafter, P2P

For example, one of the largest of the peer-to-peer file-sharing companies, LimeWire, has been ordered to cease operations as the result of a civil lawsuit. The file-sharing community, however, is still alive and well thanks to the many other providers of this type of software and services, such as FrostWire, BearShare, BitTorrent, and dozens of others. See Larry E. Daniel and Lars E. Daniel, Digital Forensics for Legal Professionals Understanding Digital Evidence From the Warrant to the Courtroom, Syngress (2012) at 253

11

Peter S. Menell and David Nimmer, Legal Realism in Action: Indirect Copyright Liabilitys Continuing Tort Framework and Sonys De Facto Demise, 55 UCLA L. Rev. 143 (2009) at 179-186 (thoroughly explaining how each P2P software works). See also Seth A. Miller, Peer-to-Peer File Distribution: an Analysis of Design, Liability, Litigation, and Potential Solutions, 25 Rev. Litig. 181 (2006) at 190-192.

12 13

Daniel, Supra at 253.

Napster, the first model, had centralized system, which has central server. The Napster ran centralized servers, providing a clear target for civil or criminal legal action. On the contrary, the next generation of file-sharing technologies such as Gnutella and Freenet allow users to make their own files available to others, as well as to access the files of others who use the software.

14

Jesse M. Feder, Is Betamax Obsolete? Sony Corp. of America v. Universal City Studios, Inc. in the Age of Napster, 37 Creighton L. Rev. 859, 863 (2004).

Seung Joo, Beik

Internet and Computer Crime Seminar

Prof. Joseph v. Demarco

In the recent series of cases, involving P2P, courts have struggled with the application of the Sony safe harbor.15 In none of these cases have courts immunized the defendants from liability. The discussion below examines the trio of digital age P2P technology cases -- Napster, Aimster, and Grokster. a. Napster In A&M Records, Inc. v. Napster, Inc.,16 the Ninth Circuit found that the designer and distributor of a software program were liable for contributory infringement. 17 The court emphasized that Napster materially contributes to the infringing activity.18 With respect to Contributory Infringement, the court found that when the RIAA notified the infringement the requirement for liability had been satisfied; in fact, Napster failed to remove those infringing files.19 The court also focused on the fact that the systems very purpose and architecture aided the users infringing conduct. 20 In terms of Vicarious infringement, Napster had a direct financial interest in the infringement, because the free downloading induced more users to register with the service.21 The court further held that Napster had the right and ability to control and supervise infringement because Napster did nothing to remove infringing files.22 b. Aimster23 Similarly, in Aimster, The Seventh Circuit ruled that if the infringing uses are substantial then to avoid liability as a contributory infringer the provider of the service must show that it would have been disproportionately costly for him to eliminate or at least reduce substantially the infringing uses.24 The court addressed willful blindness. The court held that Aimster could not avoid the knowledge element of contributory infringement by insulating itself from actual knowledge of infringing uses and was willfully blind.25 c. Grokster

15

Sony Corp. of America v. Universal City Studios Inc., 464 U.S. 417 (1984) (If the product was capable of substantial noninfringing use and that therefore the defendant could not be held liable for the actions of their users.)

16 17 18 19 20 21

A&M Records, Inc. v. Napster, Inc., 239 F.3d 1004 (9th Cir. 2001) Id. at 1020. Id. at 1022 (quoting Napster, 114 F. Supp. 2d at 920) (citation omitted). Napster, 239 F.3d at 1022. Id. Id. Id. Unlike Napster, Aimsters peer-to-peer technology did not rely upon a central server to facilitate the sharing of files. In re Aimster Copyright Litig., 334 F.3d (7th Cir. 2003) at 653. Id.at 651.

22

23 24

25

Seung Joo, Beik

Internet and Computer Crime Seminar

Prof. Joseph v. Demarco

The Ninth Circuit decided in Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios, Inc. v. Grokster Ltd.26 that P2P software vendors could not be held liable for their users copyright infringement over which they had no control.27 However, the Supreme Court found Grokster liable for Contributory Infringement by intentionally inducing or encouraging direct infringement. The Court indicated the standard for inducement liability is providing or creating a service with the object of promoting its use to infringe copyright.28 The Court then held that one who distributes a device with the object of promoting its use to infringe copyrights, as shown by clear expression or other affirmative steps taken to foster infringement, is liable for the resulting [third-party] acts of [copyright] infringement.29 The Court held that a lack of specific knowledge of infringement and a failure to act upon that lack of knowledge did not bar the application of other theories of secondary liability. 30 Justice Souter stressed that the correct legal principle on which to rule is the common-law concept of inducement infringement.31 Then, the Court continued to discuss the intent of the defendants stating that Grokster acted with a purpose to cause copyright violations by use of software suitable for illegal use.32 The Court found three specific qualities of the distributors particularly noteworthy: First, companies exhibited a desire to satisfy the demand for illegal downloading of copyrighted materials by expressly attempting to appeal to previous users of Napster. 33 Second, companies

26

Grokster, 380 F.3d 1154 (9th Cir.), cert. granted, 125 S. Ct. 686 (2004). The plaintiffs--music and movie industry organizations, songwriters, and publishers--brought actions for contributory and vicarious copyright infringement arguing that the vast majority of the software use [was] for copyright infringement.

27

Id. at 1157, 1163. In fact, the court made a key distinction between the Napster and Grokster technologies: essentially, there is a large difference between deleting a filename from ones own computer (which Napster had a duty to do) and altering software located on anothers computer (which the plaintiffs argued Grokster should do).

28

Id. at 914, 937. (The inducement rule, ... premises liability on purposeful, culpable expression and conduct, and thus does nothing to compromise legitimate commerce or discourage innovation having a lawful promise.)

29 30 31

Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios, Inc. v. Grokster, Ltd.,125 S. Ct. 2764 (2005) at 2780. Grokster, 125 S. Ct. at 2779.

Id. at 2779. The Court explained, Inducement infringement refers to situations where evidence demonstrates more than mere knowledge, to the point where there are statements or actions promoting infringement. Inducement infringement often occurs where one entic[es] or persuad[es] another to engage in infringing activities. Id. (citing BLACKS LAW DICTIONARY 790 (8th ed. 2004)). Common law has long recognized the existence of liability on the basis of inducement infringement. See, e.g., Kalem Co. v. Harper Bros., 222 U.S. 55, 62-63 (1911) cited in Grokster, 125 S. Ct. at 2779.

32 33

Id.

Id. Because Napster was a program whose users engaged in copious amounts of known copyright infringement, the Court derived a great deal of significance from both Groksters and StreamCasts attempts to divert old Napster customers to its own programs. It also appears from the record that the companies would respond to emails that inquired about how to download copyrighted materials that were available through use of their programs. See id. at 2772.

Seung Joo, Beik

Internet and Computer Crime Seminar

Prof. Joseph v. Demarco

did not create any filter in order to prevent the infringing activities.34 Third, the defendants had a desire to increase the infringement.35 In other words, the more the defendants software is used, the more advertising revenue they earn.36 Thus, the Court concluded that unlawful intent could be inferred.37 III. Implication of the Cases

1. The Nature of the Civil Liability: Contributory and Vicarious Liability Copyright infringement liability can be imputed onto those who indirectly infringe. Two indirect infringing claims have been considered in the P2P litigation: contributory and vicarious liability for copyright infringement.38 One is liable for contributory infringement when one knowingly contributes to the infringing conduct of another.39 Contributory infringement requires: (1) direct infringement by a third party; (2) actual or constructive knowledge that a third party was directly infringing; and (3) a material contribution to the infringing activities.40 Additionally, contributory infringement is found when a contributory infringer: (1) has direct or constructive knowledge of a third partys infringing activity; and (2) induces, 41 causes, or materially contributes to the infringing conduct.42

34

Id. at 2781. The district court and the Ninth Circuit had determined that the defendants failure to develop filtering tools was not essential to the holding, as that would place an independent duty on the defendants to monitor users activity. See MGM Studios Inc. v. Grokster, Ltd., 380 F.3d 1154, 1164-66 (9th Cir. 2004). Instead, the Court notes that StreamCast even took the step of rejecting another companys offer to monitor infringement and blocked the IP addresses of entities that it felt were engaged in any such monitoring. Grokster, 125 S. Ct. at 2774.

35

See id. at 2781-82. Id.at 2782. Id.

36 37

38

In re Aimster Copyright Litig., 334 F.3d 643 (7th Cir. 2003); A&M Records, Inc. v. Napster, Inc., 239 F.3d 1004, 1022 (9th Cir. 2001).

39 40

Fonovisa, Inc. v. Cherry Auction, Inc., 76 F.3d 259, 264 (9th Cir. 1996).

In re Napster, Inc. Copyright Litig., 377 F. Supp. 2d 796, 801 (N.D. Cal. 2005) (citing A&M Records, Inc. v. Napster, Inc., 239 F.3d 1004, 1013 n.2, 1019-22 (9th Cir. 2001).

41

See Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios, Inc. v. Grokster, Ltd., 545 U.S. 913, 930 (2005) (One infringes contributorily by intentionally inducing or encouraging direct infringement); Perfect 10, 487 F.3d at 727 ([A]n actor may be contributorily liable [under Grokster] for intentionally encouraging direct infringement if the actor knowingly takes steps that are substantially certain to result in such direct infringement); Napster, 239 F.3d at 1019 (stating that the defendant incurs contributory liability when they [e]ngage in personal conduct that encourages or assists the infringement (quoting Matthew Bender & Co. v. West Publg Co., 158 F.3d 693, 706 (2d Cir. 1998)).

42

Perfect 10, Inc. v. Visa Intl Serv. Assn, 494 F.3d 788, 795 (9th Cir. 2007) (quoting Ellison v. Robertson, 357 F.3d 1072, 1076 (9th Cir. 2004) (citation omitted)); see also Fonovisa, Inc. v. Cherry Auction, Inc., 76 F.3d 259, 264 (9th Cir. 1996) (discussing the elements of contributory infringement).

Seung Joo, Beik

Internet and Computer Crime Seminar

Prof. Joseph v. Demarco

Moreover, the Supreme Court explained that vicarious liability is imposed in virtually all areas of the law.43 In P2P litigation, the elements of vicarious liability are met: (1) where defendant has the right and ability to supervise or control; and (2) defendant has financial interest in infringing activity.44 2. Is There Any Clear Line between the Two Liabilities? Theoretically, contributory and vicarious liability can be clearly distinguished. Each element, however, functioned interactively when the court assess the elements. It should be noted that the elements of each liability were assessed, but not under their correctly-named theories. For example, in the three cases above, the element of control, usually assessed under vicarious liability, was assessed under contributory liability. Also, the element of a financial benefit was analyzed under a theory of contributory liability.

Now, consider each element in criminal aspect. It is not astonishing to find civil and criminal liability have something in common: liability for abetting or aiding. Thus, we can build up a theory that P2P service Provider abetted copyright infringement of users. IV. Possible Criminal Liability Aid and Abetting and Korean Supreme Courts Position

The Aimster court likened Aimster to an aider and abettor of criminal activity. 45 Also, Justice Souter, in Grokster, noted that the respondents acted with an unlawful objective in three aspects: (1) marketing the illicit use of their programs; (2) failing to attempt to curb the illegal use of the products; and (3) making a profit as a result of the illegal activities by users. 46 The courts saying is that the defendant is liable if the defendant knowingly aided and abetted anothers direct infringement.47 The Supreme Court inferred this intent from the behaviors of service provider and the characters of that service. Mens rea requirement for criminal penalty cannot be the barrier against criminal prosecution. The essential elements48 of aiding and abetting are (1) an act by the defendant that contributes to the commission of the crime, and (2) an intention to aid in the commission of the

43 44

Sony Corp. of America v. Universal City Studios, Inc. , 464 U.S. 417, 435 (1984). Gershwin, 443 F.2d at 1162. Id.at 646. See id. at 2781. Grokster , 125 S. Ct. at 2776.

45

46 47 48

Naturally, it is also required (3) that the accused assisted or participated in the commission of the underlying offense; and (4) that someone committed the underlying substantive offense. It is also as same as civil liability. However, this Note skipped the comparison because the direct infringers conducts clearly constitute principal copyright crime. See infra III. 1.

Seung Joo, Beik

Internet and Computer Crime Seminar

Prof. Joseph v. Demarco

crime.49 Under the circumstances above, provider of Grokster, it can be seen that aiding and abetting law applies the same basic requirements as contributory infringement law.50 For the plausible argument, it is significant to review the Korean Supreme Court decision in criminal case of P2P. According to the Court, the Soribada,51 P2P Service Network, was liable for abetting the Internet users copyright infringement,52 stating that [a]betting the direct infringement of copyright protected by Copyright Law includes all direct or indirect acts that assist the infringement or that make it easier. Furthermore, concerning intent requirement, the Korean Supreme Court expanded its meaning and pointed out that [I]t is sufficient to be convicted, if the defendant knew somebody infringed copyright. He did not need to know exactly who the infringers are or how they did it as long as he realized his network was used for infringement. 53 Thus, P2P service providers are liable for abetting direct copyright infringement. For example, in Grokster, the plaintiffs had notified the defendants of millions of copyrighted files that could be downloaded via the software. 54 Moreover, internal communications and advertisements showed the defendants intent to retain previous Napster users. 55 Additionally, Groksters principal object was use of their software to download copyrighted works because defendants generated income by selling advertising space.56 Finally, the Court pointed out that the defendants basically covered their ears and closed their eyes by consciously deciding not to monitor infringement.57 In sum, the software distributors knew, or should have known, about the users infringing activities. Therefore, P2P service provider abetted the direct infringement. V. Conclusion

There are no easy answers to the questions posed by the advent of online piracy. Some

49

United States v. Graham, 622 F.3d 445, (6th Cir.2010); United States v. Ionutescu, No. CR-08-0612, 2009 WL 5174270 (D.Ariz. Dec. 21, 2009).

50

Mark Bartholomew and Patrick F. McArdle, Causing Infringement, 64 Vand. L. Rev. 675, 696 (2011). Soribada means the Sea of Sound in English. It is a P2P service software that allows people to downroad free music files.

51 52

Korean Supreme Court [S. Ct.] 2005Do872, Dec. 14, 2007 (S. Kor.). The nature of P2P service and the relevant facts of case were exactly same as Grokster.

53

Id. This decision was the first one in the world that addressed whether a P2P service provider may be liable in criminal case. Id.at 2772. Id. Id.at 2774. Id.at 2781.

54 55 56 57

Seung Joo, Beik

Internet and Computer Crime Seminar

Prof. Joseph v. Demarco

commentators assert that the best solution may be as simple as educating the public, especially younger generations.58 Others warn people not to be involved in crime when they use P2P.59 Moreover, in litigation world, the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) has sued over 35,000 people for the illegal file-sharing of music.60 However, very few adult file-sharers are not aware that receiving copyrighted material for free is illegal. That is, P2P users continue to download copyrighted material for other reasons entirely unrelated to lack of education. Therefore, educational campaigns featuring wealthy artists are unlikely to gain much sympathy from the average consumer. 61 Also, civil suits either against P2P service provider or against individuals has been proved that such suits have failed to prevent copyright infringement.

In these embarrassing situations, it is high time to consider prosecutorial intervention. For the individuals, they always have incentives to search for free files because they act like economic animals. For P2P service providers, civil suit is not the punishment at all unless the damages could totally eclipse the revenues. They are economic animal as well. Thus, criminal prosecution may deter the service providers bad acts because criminal sanction can reduce the illegal service and the source of infringement supply. Practically speaking, it is not hard for a prosecutor to prosecute P2P service providers under Grokster. If we have precedents for civil liability, and if civil and criminal liability is naturally identical in this matter, there is no reason to exclude criminal liability even though we have clear statutes that permits criminal prosecution. Once again, why not?

58

Recent Cases, Copyright Law -- Ninth Circuit Holds That Computer File-Sharing Software Vendors Are Not Liable For Users Copyright Infringement -- Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios, Inc. v. Grokster Ltd., 380 F.3d 1154 (9th Cir.), cert. granted, 125 S. Ct. 686 (2004), 118 Harv. L. Rev. 1761, 1768 (2005).

59

There have been some public warnings of the danger of P2P published by Attorney General, FTC, and FBI. See Darren Gelbera, Cybercrimes: File-Sharing Programs Violating Copyright and Child Pornography Distribution Laws, 255-DEC N.J. Law. 66, 67 (2008).

60

William Henslee, Money for Nothing and Music for Free? - Why the RIAA Should Continue to Sue Illegal File-Shares, 9 J. Marshall Rev. Intell. Prop. L. 1 (2009). He concluded that The RIAA should continue to pursue illegal uploaders and downloaders in court to ensure that no one is falsely accused of copyright infringement. Id. at 22.

61

Michael Suppappola, The End of the World as We Know It? The State of Decentralized Peer-to-Peer Technologies in the Wake of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios v. Grokster, 4 Conn. Pub. Int. L.J. 122,174(2004).

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5784)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Law of Torts Project - Semester Two (Final Draft)Document13 pagesLaw of Torts Project - Semester Two (Final Draft)tanyaNo ratings yet

- NFA Citizen's CharterDocument53 pagesNFA Citizen's CharterpastorjeffgatdulaNo ratings yet

- Media Laws and Freedom of Expression and Press in Bangladesh AssignmentDocument18 pagesMedia Laws and Freedom of Expression and Press in Bangladesh AssignmentNabil OmorNo ratings yet

- College of Engineering Pune Business Law and Ethics Essentials of a Valid ContractDocument7 pagesCollege of Engineering Pune Business Law and Ethics Essentials of a Valid ContractDevshri UmaleNo ratings yet

- KARNATAKA BORSTAL SCHOOLS ACTDocument14 pagesKARNATAKA BORSTAL SCHOOLS ACTShreyas KatugamNo ratings yet

- Shareholders' AgreementDocument23 pagesShareholders' AgreementJayzell Mae FloresNo ratings yet

- 4 - The Iloilo Ice and Cold Storage Company V, Publc Utility Board G.R. No. L-19857 (March 2, 1923)Document13 pages4 - The Iloilo Ice and Cold Storage Company V, Publc Utility Board G.R. No. L-19857 (March 2, 1923)Lemuel Montes Jr.No ratings yet

- Brand Ambassador Contract TemplateDocument8 pagesBrand Ambassador Contract TemplateKC Onofre100% (5)

- BIR Form 1702-ExDocument7 pagesBIR Form 1702-ExShiela PilarNo ratings yet

- Criminal Procedure On Rights of Arrested PersonDocument9 pagesCriminal Procedure On Rights of Arrested PersonGrace Lim OverNo ratings yet

- Law On Obligation and Contract: Here Is Where Your Presentation BeginsDocument35 pagesLaw On Obligation and Contract: Here Is Where Your Presentation BeginsKent Giane GomezNo ratings yet

- Bill of Rights 1689Document1 pageBill of Rights 1689yojustpassingbyNo ratings yet

- Frequently Ask Question - BudgetingDocument28 pagesFrequently Ask Question - BudgetingNrf Frn100% (1)

- IPRDocument34 pagesIPRTusharGuptaNo ratings yet

- PERSONS AND FAMILY RELATIONS UNDER PHILIPPINE LAWDocument4 pagesPERSONS AND FAMILY RELATIONS UNDER PHILIPPINE LAWCathyrine JabagatNo ratings yet

- Tuatis VS SPS Escol DigestDocument3 pagesTuatis VS SPS Escol DigestJJ CaparrosNo ratings yet

- Oath of OfficeDocument1 pageOath of OfficeKim Patrick VictoriaNo ratings yet

- 200-CIR v. Magsaysay Lines Inc. G.R. No. 146984 July 28, 2006Document4 pages200-CIR v. Magsaysay Lines Inc. G.R. No. 146984 July 28, 2006Jopan SJNo ratings yet

- Aguas Vs de LeonDocument7 pagesAguas Vs de LeonMickoy CalderonNo ratings yet

- Mitskog v. MSPB (2016-2359)Document4 pagesMitskog v. MSPB (2016-2359)FedSmith Inc.No ratings yet

- Introduction To The Law of ContractDocument34 pagesIntroduction To The Law of ContractCharming MakaveliNo ratings yet

- Statutes and Its PartsDocument24 pagesStatutes and Its PartsShahriar ShaonNo ratings yet

- Revocable Living TrustDocument14 pagesRevocable Living TrustJack100% (7)

- March14.2016passage of Proposed Tricycle Driver Safety Act SoughtDocument2 pagesMarch14.2016passage of Proposed Tricycle Driver Safety Act Soughtpribhor2100% (1)

- Petitioner-Appellee vs. vs. Respondent Appellant Solicitor General Antonio Barredo, Assistant Solicitor General Antonio G. Ibarra and Solicitor Bernardo P. Pardo Sta. Ana and MarianoDocument3 pagesPetitioner-Appellee vs. vs. Respondent Appellant Solicitor General Antonio Barredo, Assistant Solicitor General Antonio G. Ibarra and Solicitor Bernardo P. Pardo Sta. Ana and MarianoLDCNo ratings yet

- Che Omar Che Soh V PPDocument3 pagesChe Omar Che Soh V PPNadia Ezzati نادية اززاتي67% (6)

- Schools Division of Batanes: Bid Evaluation ReportDocument2 pagesSchools Division of Batanes: Bid Evaluation Reportaracelipuno100% (3)

- Tabasa v. CADocument9 pagesTabasa v. CALyceum LawlibraryNo ratings yet

- Tobacco Free Workplace PolicyDocument3 pagesTobacco Free Workplace PolicyJustinFinneranNo ratings yet

- Republic of The Philippines: PlaintiffDocument4 pagesRepublic of The Philippines: PlaintiffJomik Lim EscarrillaNo ratings yet