Professional Documents

Culture Documents

How Sondheim Found His Sound

Uploaded by

Andrew MilnerOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

How Sondheim Found His Sound

Uploaded by

Andrew MilnerCopyright:

Available Formats

Roots, Sondhelm-style

Swayne explores the influences of Sondheim's musical genius

riting a book of musical analysis for the general public is risky business. Do you patronize your readers by breathlessly declaring, as Martin Gottfried did in his chatty coffee-table book Sandheim (1993). that "a song is made up of music and lyrics"? Or do you resort to academic jargon in the manner of Stephen Banfield in his massive Sondheim 's Broadway Musicals (1993), which virtually requires a master's degree in musicology? Steven Swayne has found the middle way in Hcne Sondheim Found His Sound (University of Michigan Press, 2005) with his examination of the primary influences on Sondheim's music, offering academic references in a manner that even a musical neophyte can appreciate. An associate professor of music at Dartmouth College, Swayne devotes the first part of his book to Sondheim's collegiate beginnings, writing the famous "apprentice" musicals under Oscar Hammerstein IPs mentoring while studying music at Williams College under Robert Barrow. Sondheim, Swayne asserts, "learned how to write music mainly from Barrow. He learned how to create a character mainly from Hammerstein. He learned how to structure a scene mainly from film." Swayne cites Hammerstein's no-nonsense mentoring about Sondheim's post-college musical, Climb High: "I want you to say, 'Can I interest an audience in this to the extent that I am interested in it?'" Swayne adds that Hammerstein "presented Sondheim with three main characteristics of solid writing. 'I know that the smallest kind of story can be made to be earthshaking if the characters are examined closely enough, and if the choice of incident is ingenious enough, and if the narrative of the incident is told with enough depth and human observation.' That Sondheim met these three conditions in all his mature shows reveals the extent of his indebtedness to Hammerstein's tutelage." Swayne also examines the impact Harold Arlen's composing had on Sondheim's songwriting. Sondheim told Swayne that Arlen's "harmonic structures and his harmonies are, to me, endlessly rich, inventive and fascinating, and I never tire of his music." Swayne contends that "What Can "Vbu Lose?" from Dick Tracy (which he analyzes in detail) echoes Arlen's harmonics and song structure. Swayne's book also studies Sondheim's movie influences, particularly the films of Alain Resnais, whose Stavisky was scored by Sondheim. Swayne observes, "When the complexities of the Sondheim musicals of the seventies and beyond are bracketed by the French New Wave on one side and by Sondheim's own comments about the nom-elle vague on the other, the influence of the French New Wave upon Sondheim virtually establishes

= E . -..: -.-

itself. Sondheim trafficked in a popular medium and yet brought it to an intellectual severity, a politique d'auteur and even a manner of visualization that resemble Resnais' films in particular." The book's 69-page centerpiece of the book is Swayne's masterful dissection of "Putting It Together" from Sunday in the Park isAth George: "What better song, then, in which to examine Sondheim's amalgamations and his 'bit by bit' manner of construction than the song that most closely scrutinizes the art of making art?" It's a wonderful section, with copious musical quotations displaying the parallels between "Putting It Together" and its first-act antecedents "The Day Off" and "Finishing the Hat." Swayne analyzes the song's cinematic techniques. " [A] look at the vocal score quickly reveals the song's structural complexity and similarity to a composite cinematic scene," where 17 different characters engage in conversation with musical equivalents of freezeframe cuts and camera pans. Swayne concludes that the song "is unapologetically collaborative, and it shows what can result from successful collaboration. On this level, it is at the vanguard of musical theater writing." For all the examination of the composing influences, Swayne offers little insight into Sondheim's lyric-writing influences. It would have been useful to compare and contrast Sondheim's early lyrics with those of Hammerstein, Frank Loesser and Dorothy Fields. And while we're treated to snippets of Sondheim-written dialogue from his collegiate work, Swayne does not study the mature scripts for The Last of Sheila or Getting Away With Murder. Svvayne closes his "Sondheim the Tunesmith" chapter with a Sondhcimesque verse: "It's no sin that Berlin Sondheim only pastiches/Like Porter, his forte's in the words he unleashes ..." His verse comes off as too clever by half. These minor flaws aside, Swayne has put together a well-researched, coherent look at where it all began for Sondheim. For trivia buffs. Swayne lists the English and drama courses Sondheim took at Williams, as well as a cross-section of the composers in Sondheim's mammoth record collection (Chopin, Hindemith and Prokofiev are each d represented). Hem- Sondheim Found Hit could become a standard text for iotmdbna lege musical theatre courses and sfandd eufcfafc Svvayne as a prominent theatre I ies of "What Can You Lost Together" are so on the i he would bring his; an entire Sondheim score. I

::; -: -r

Phaadclphia Oty Paper.

The Sondheim Review 49

You might also like

- Stephen Sondheim and the Reinvention of the American MusicalFrom EverandStephen Sondheim and the Reinvention of the American MusicalRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (3)

- Sondheim Hammerstein EssayDocument18 pagesSondheim Hammerstein Essaygeorge8luis100% (1)

- Sondheim Seminar Spring 2011 SYLLABUS 1.30.11Document11 pagesSondheim Seminar Spring 2011 SYLLABUS 1.30.11George Lazaris100% (1)

- Sondheim Sings, Volume 1 CDDocument2 pagesSondheim Sings, Volume 1 CDAndrew MilnerNo ratings yet

- Finishing The Hat NotesDocument3 pagesFinishing The Hat NotesGail LeondarWrightNo ratings yet

- Off-Broadway Musicals since 1919: From Greenwich Village Follies to The Toxic AvengerFrom EverandOff-Broadway Musicals since 1919: From Greenwich Village Follies to The Toxic AvengerNo ratings yet

- Becoming Stephen SondheimDocument402 pagesBecoming Stephen SondheimDavid100% (2)

- Musical Theatre Choreography: Reflections of My Artistic Process for Staging MusicalsFrom EverandMusical Theatre Choreography: Reflections of My Artistic Process for Staging MusicalsNo ratings yet

- Sondheim's TechniqueDocument16 pagesSondheim's TechniqueNick Bottom100% (2)

- The World of Musical Comedy: The Story of the American Musical StoryFrom EverandThe World of Musical Comedy: The Story of the American Musical StoryNo ratings yet

- Our Musicals, Ourselves: A Social History of the American Musical TheatreFrom EverandOur Musicals, Ourselves: A Social History of the American Musical TheatreRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (6)

- Musical Misfires: Three Decades of Broadway Musical HeartbreakFrom EverandMusical Misfires: Three Decades of Broadway Musical HeartbreakNo ratings yet

- The Enraged Accompanist's Guide to the Perfect AuditionFrom EverandThe Enraged Accompanist's Guide to the Perfect AuditionRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Sondheim Piano Sonata AnalysisDocument48 pagesSondheim Piano Sonata AnalysisDa Bomshiz100% (2)

- I'm Getting Murdered In The Morning: Play Dead Murder Mystery PlaysFrom EverandI'm Getting Murdered In The Morning: Play Dead Murder Mystery PlaysNo ratings yet

- Sondheim PDFDocument585 pagesSondheim PDFOzou'ne Sundalyah88% (8)

- Something Wonderful: Rodgers and Hammerstein's Broadway RevolutionFrom EverandSomething Wonderful: Rodgers and Hammerstein's Broadway RevolutionRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (39)

- How to Survive a Killer Musical: Agony and Ecstasy on the Road to BroadwayFrom EverandHow to Survive a Killer Musical: Agony and Ecstasy on the Road to BroadwayNo ratings yet

- GEMIGNANI: Life and Lessons from Broadway and BeyondFrom EverandGEMIGNANI: Life and Lessons from Broadway and BeyondRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Vocal Score: Beggar's Holiday, Duke Ellington Broadway musical: Beggar's Holiday, the only Broadway Musical by Duke EllingtonFrom EverandVocal Score: Beggar's Holiday, Duke Ellington Broadway musical: Beggar's Holiday, the only Broadway Musical by Duke EllingtonNo ratings yet

- Stephen Sondheim and His Filmic InfluencesDocument89 pagesStephen Sondheim and His Filmic InfluencesJamesRuth67% (3)

- Moschler, David - Compositional Style and Process in Rodgers & Hammerstein's CarouselDocument99 pagesMoschler, David - Compositional Style and Process in Rodgers & Hammerstein's CarouselDave Moschler75% (4)

- The Book of Broadway Musical Debates, Disputes, and DisagreementsFrom EverandThe Book of Broadway Musical Debates, Disputes, and DisagreementsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- A Study Guide for Stephen Sondheim's "Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street" (film entry)From EverandA Study Guide for Stephen Sondheim's "Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street" (film entry)No ratings yet

- SondheimDocument8 pagesSondheimBridget ElizabethNo ratings yet

- Short Plays: Good Hidings, FINE, The Stars are Made of ConcreteFrom EverandShort Plays: Good Hidings, FINE, The Stars are Made of ConcreteNo ratings yet

- Broadway and The Non-ConformistDocument6 pagesBroadway and The Non-ConformistJesse Cook-HuffmanNo ratings yet

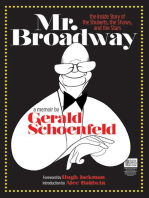

- Mr. Broadway: The Inside Story of the Shuberts, the Shows and the StarsFrom EverandMr. Broadway: The Inside Story of the Shuberts, the Shows and the StarsRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (2)

- Yip Harburg: Legendary Lyricist and Human Rights ActivistFrom EverandYip Harburg: Legendary Lyricist and Human Rights ActivistNo ratings yet

- October 1, 1951 at Ebbets FieldDocument3 pagesOctober 1, 1951 at Ebbets FieldAndrew MilnerNo ratings yet

- 1935 Game Story For SABR Shibe Park BookDocument5 pages1935 Game Story For SABR Shibe Park BookAndrew MilnerNo ratings yet

- Gina Kolata Author AppearanceDocument1 pageGina Kolata Author AppearanceAndrew MilnerNo ratings yet

- Yankee Stadium 1977 All-Star GameDocument4 pagesYankee Stadium 1977 All-Star GameAndrew MilnerNo ratings yet

- A Necessary Evil Book ReviewDocument1 pageA Necessary Evil Book ReviewAndrew MilnerNo ratings yet

- Hughie McLoonDocument2 pagesHughie McLoonAndrew MilnerNo ratings yet

- Charlie Murphy Book ReviewDocument2 pagesCharlie Murphy Book ReviewAndrew MilnerNo ratings yet

- Casino of DreamsDocument1 pageCasino of DreamsAndrew MilnerNo ratings yet

- Phillies' All-Time Blowout GamesDocument6 pagesPhillies' All-Time Blowout GamesAndrew MilnerNo ratings yet

- TRIANGLE: THE FIRE THAT CHANGED AMERICA Book ReviewDocument1 pageTRIANGLE: THE FIRE THAT CHANGED AMERICA Book ReviewAndrew MilnerNo ratings yet

- Singing Out LoudDocument1 pageSinging Out LoudAndrew MilnerNo ratings yet

- Andrew J. Milner: Everything Sondheim (A/k/a The Sondheim Review), 2004-Present. Cover Books, RecordsDocument2 pagesAndrew J. Milner: Everything Sondheim (A/k/a The Sondheim Review), 2004-Present. Cover Books, RecordsAndrew MilnerNo ratings yet

- ST. JAMES ENCYCLOPEDIA: Carl ReinerDocument2 pagesST. JAMES ENCYCLOPEDIA: Carl ReinerAndrew MilnerNo ratings yet

- 02 When Broadway Went To Hollywood PDFDocument1 page02 When Broadway Went To Hollywood PDFAndrew MilnerNo ratings yet

- Philly City Paper GoodbyeDocument1 pagePhilly City Paper GoodbyeAndrew MilnerNo ratings yet

- Low Self-Esteem ClubDocument2 pagesLow Self-Esteem ClubAndrew MilnerNo ratings yet

- Take Me OutDocument2 pagesTake Me OutAndrew MilnerNo ratings yet

- TC1 Response To A Live Employer Brief: Module Code: BSOM084Document16 pagesTC1 Response To A Live Employer Brief: Module Code: BSOM084syeda maryemNo ratings yet

- Motion To Revoke Detention OrderDocument21 pagesMotion To Revoke Detention OrderStephen LoiaconiNo ratings yet

- Classroom of The Elite Year 2 Volume 4Document49 pagesClassroom of The Elite Year 2 Volume 4ANANT GUPTANo ratings yet

- UEFA Stadium Design Guidelines PDFDocument160 pagesUEFA Stadium Design Guidelines PDFAbdullah Hasan100% (1)

- Azevedo Slum English 1926Document90 pagesAzevedo Slum English 1926Nealon Isaacs100% (1)

- KISS Notes The World CommunicatesDocument30 pagesKISS Notes The World CommunicatesJenniferBackhus100% (4)

- LLCE CoursDocument18 pagesLLCE CoursDaphné ScetbunNo ratings yet

- Dacera Vs Dela SernaDocument2 pagesDacera Vs Dela SernaDarlo HernandezNo ratings yet

- If Tut 4Document7 pagesIf Tut 4Ong CHNo ratings yet

- Intersection of Psychology With Architecture Final ReportDocument22 pagesIntersection of Psychology With Architecture Final Reportmrunmayee pandeNo ratings yet

- Ejercicios de Relative ClausesDocument1 pageEjercicios de Relative ClausesRossyNo ratings yet

- Conference Diplomacy: After Kenya's Independence in 1963, A Secession Movement Begun inDocument3 pagesConference Diplomacy: After Kenya's Independence in 1963, A Secession Movement Begun inPeter KNo ratings yet

- Indian Standard: General Technical Delivery Requirements FOR Steel and Steel ProductsDocument17 pagesIndian Standard: General Technical Delivery Requirements FOR Steel and Steel ProductsPermeshwara Nand Bhatt100% (1)

- Film Viewing RomeroDocument3 pagesFilm Viewing RomeroJenesis MuescoNo ratings yet

- Absolute Community of Property vs. Conjugal Partnership of GainsDocument7 pagesAbsolute Community of Property vs. Conjugal Partnership of GainsJill LeaNo ratings yet

- Sacred Books of The East Series, Volume 47: Pahlavi Texts, Part FiveDocument334 pagesSacred Books of The East Series, Volume 47: Pahlavi Texts, Part FiveJimmy T.100% (1)

- A Seminar Report On Soft Skills: Submitted To Visvesvaraya Technological University, BelgaumDocument18 pagesA Seminar Report On Soft Skills: Submitted To Visvesvaraya Technological University, Belgaumvishal vallapure100% (1)

- Amlogic USB Burning Tool V2 Guide V0.5Document11 pagesAmlogic USB Burning Tool V2 Guide V0.5Andri R. LarekenNo ratings yet

- Agatthiyar's Saumya Sagaram - A Quick Summary of The Ashta KarmaDocument5 pagesAgatthiyar's Saumya Sagaram - A Quick Summary of The Ashta KarmaBujji JohnNo ratings yet

- I/O Reviewer Chapter 1Document3 pagesI/O Reviewer Chapter 1luzille anne alertaNo ratings yet

- BÀI TẬP ÔN HSG TỈNHDocument12 pagesBÀI TẬP ÔN HSG TỈNHnguyễn Đình TuấnNo ratings yet

- Process Audit Manual 030404Document48 pagesProcess Audit Manual 030404azadsingh1No ratings yet

- Daad-Courses-2019-09-08 6Document91 pagesDaad-Courses-2019-09-08 6Kaushik RajNo ratings yet

- Voloxal TabletsDocument9 pagesVoloxal Tabletselcapitano vegetaNo ratings yet

- Fugacity and Fugacity CoeffDocument9 pagesFugacity and Fugacity CoeffMujtabba AlkhtatNo ratings yet

- Machine Learning and Iot For Prediction and Detection of StressDocument5 pagesMachine Learning and Iot For Prediction and Detection of StressAjj PatelNo ratings yet

- Test 04 AnswerDocument16 pagesTest 04 AnswerCửu KhoaNo ratings yet

- EBM SCM ReportDocument22 pagesEBM SCM ReportRabia SiddiquiNo ratings yet

- Silk Road ActivityDocument18 pagesSilk Road Activityapi-332313139No ratings yet

- DPC Rough Draft by Priti Guide (1953)Document6 pagesDPC Rough Draft by Priti Guide (1953)Preeti GuideNo ratings yet