Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Untitled

Uploaded by

snaip1370Original Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Untitled

Uploaded by

snaip1370Copyright:

Available Formats

Cayman Islands National Biodiversity Action Plan 2009 3.M.3.

1 Marine Species - Reptiles Marine Turtles

Rev: 19 March 2012

DIGITALDIVER.NET

Marine Turtles Chelonia mydas, Caretta caretta, Eretmochelys imbricata, Dermochelys coriacea Taxonomy and Range Kingdom: Animalia, Phylum: Chordata, Class: Reptilia, Order: Testudines, Family: Cheloniidae There are seven living species of marine turtle, four of which have been documented in the Cayman Islands. These are the Green Chelonia mydas, the Loggerhead Caretta caretta, the Leatherback Dermochelys coriacea, and the Hawksbill Eretmochelys imbricata. Status Distribution: Circum-global. Conservation: Green and Loggerhead Turtles are classified as endangered, while Hawksbill and Leatherback Turtles are critically endangered (IUCN Red List 2008). Cayman Island nesting: Green, Loggerhead and Hawksbill Turtle nesting is critically reduced. Leatherback nesting populations have been extirpated. Cayman Islands foraging: Hawksbill and Green Turtle foraging aggregations are apparently stable. Cayman Island nesting: Green Turtles: 17-26 nesting females. Loggerhead Turtles: 17-26 nesting females. Hawksbill and Leatherback Turtles: nesting populations believed to be extirpated. Cayman Islands foraging: Hawksbill and Green Turtles: aggregations apparently stable.

For Reference and Acknowledgement: Cottam, M., Olynik, J., Blumenthal, J., Godbeer, K.D., Gibb, J., Bothwell, J., Burton, F.J., Bradley, P.E., Band, A., Austin, T., Bush, P., Johnson, B.J., Hurlston, L., Bishop, L., McCoy, C., Parsons, G., Kirkconnell, J., Halford, S. and Ebanks-Petrie, G. (2009). Cayman Islands National Biodiversity Action Plan 2009. Cayman Islands Government. Department of Environment. Final Formatting and production by John Binns, International Reptile Conservation Foundation.

Section: 3.M.3.1 Marine Species - Reptiles - Marine Turtles

Page: 1

Legal: Marine Turtles are protected under the Marine Conservation Law (Turtle Protection Regulations). The Department of Environment is the lead body for protection. Natural History Though the vast majority of their life cycle is spent at sea, female Marine Turtles nest terrestrially, spending approximately 13 hours on shore. Marine turtle hatchlings swim offshore, entering a period of oceanic drifting known as the lost years. Though Leatherback Turtles remain primarily oceanic throughout their life cycle, most hard-shell Marine Turtles recruit to nearshore feeding grounds such as coral reefs and seagrass beds. These developmental habitats are occupied by individuals originating from many jurisdictions. Upon nearing maturity, (ca. 20 years of age), turtles leave developmental habitats and move to distant adult feeding grounds. Every few years, Marine Turtles travel hundreds or thousands of kilometers from adult feeding grounds to nesting beaches, returning to the areas where they were born to breed and nest. The Cayman Islands once supported one of the worlds largest green turtle rookeries, as well as abundant nesting by Loggerhead and Hawksbill turtles. Every summer, millions of Marine Turtles are believed to have migrated to Cayman Islands to nest, leading to reports that vessels, which have lost their latitude in hazy weather, have steered entirely by the noise which these creatures make in swimming to attain the Caymana isles. However, by the early 1800s, massive exploitation had caused the Cayman Islands nesting populations to crash. By the 20th century, the Cayman Islands rookeries were considered extinct. Systematic monitoring of marine turtle nesting beaches by Department of Environment began in 1998 and revealed that nesting by Green, Loggerhead and Hawksbill turtles persisted at critically low levels: an annual mean of 26 Green turtle nests, 26 Loggerhead nests, and <1 Hawksbill nests. In recent years, a considerable increase in Green and Loggerhead nesting has been observed, with more than 100 Green turtle nests recorded for the first time in 2008. While numbers remain low, fertilization success averages 81% for Green turtle nests and 78% for Loggerhead nests, showing no reduction in fertility relative to larger populations. Satellite tracking indicates that Cayman Islands Green Turtles travel to foraging grounds in Central America, Mexico, and the Florida keys, with their range encompassing over 2,000 km of the Caribbean coastline and the Florida Keys. This dispersion highlights the importance of broad and collaborative marine turtle management and habitat protection. In contrast, Cayman Islands Loggerhead Turtles were tracked to foraging habitats in Nicaragua, underscoring the necessity of identifying key habitats and targeting action. In addition to supporting nesting populations, the Cayman Islands host foraging aggregations of juvenile Hawksbill and Green turtles, inhabiting coral reefs, hardbottom areas, and seagrass beds. Genetic research has shown that juvenile Hawksbill turtles originate from nesting beaches spanning the Caribbean basin. For Green turtles, tag returns from the Cayman Turtle Farm show recruitment of captiveraised individuals into the wild, but a genetic study has not yet been conducted to evaluate the extent of this contribution Associated Habitats and Species for Marine Turtles ASSOCIATED HABITAT PLANS 2.M.1 Open sea 2.M.2 Coral reefs 2.M.3 Lagoons 2.M.4 Seagrass beds 2.M.5 Dredged seabed 2.S.2 Sandy beach and cobble 2.S.3 Mangrove 2.S.4 Invasive coastal plants (INVASIVE) 2.T.7 Urban and man-modified areas Current Factors Affecting Marine Turtles Legal take: under the Turtle Protection Law (1996), some twenty people remain eligible for licenses to catch turtles. The level of sea turtle nesting in the Cayman Islands is critically low, and continued legal capture of mature turtles may cause the nesting population to become extinct in the near future. Update: In 2008, legislation was amended to prohibit take of mature turtles in Cayman waters. Illegal take: reports from enforcement officers and members of the public confirm that illegal take of marine turtles is still occurring around all three islands. While prosecutions are made whenever possible, the level of sea turtle nesting in the Cayman Islands is critically low, and capture of even a small number of mature turtles could cause extinction of nesting populations or prevent them from recovering. Section: 3.M.3.1 Marine Species - Reptiles - Marine Turtles Page: 2 ASSOCIATED SPECIES PLANS

Queen Conch Strombus gigas Spiny Lobsters Panulirus argus Southern Stingrays Dasyatis americana Nassau Grouper Epinephelus striatus

Incidental and accidental capture and mortality: incidental mortality arises particularly from ingestion of fish hooks and vessel collision. Marine debris: entanglement in fishing line and ingestion of plastics contributes to a largely unqualified mortality amongst Marine Turtles. Habitat loss and degradation: nesting beach habitat has been a primary focus for development since 1960s. Beach erosion and artificial lighting have also adversely affected nesting populations. Foraging populations may be impacted by hurricanes and anthropogenic degradation of coral reefs and seagrass beds. Disease: fibropapillomatosis is a condition characterized by debilitating tumors. This disease has reached epidemic proportions in some areas. Locally, fibropapillomatosis is known to affect Green Turtles in North Sound. Opportunities and Current Local Action for Marine Turtles Marine Turtle Beach Monitoring Programme (MTBMP): since 1998 the DoE has been conducting a systematic survey along the beaches of the Cayman Islands to identifying signs. During the turtle nesting season of May-October, the beaches of the Cayman Islands are patrolled by DoE staff and trained volunteers. Data collected is used to assess the quantity, frequency and distribution of nesting, and to aid conservation efforts. The MTBMP has recently expanded to incorporate attaching satellite transmitters to postnesting female turtles and monitoring their movements once they leave the nesting beaches in the Cayman Islands. Movements of Cayman sea turtles can be viewed at http://www.seaturtle.org/tracking. In-Water Programme: DoE has carried out an intensive in-water monitoring programme since 2000. Throughout the year, sea turtles are captured, tagged, and released off the shores of Grand Cayman and Little Cayman, to assess population trends, and determine migration patterns, habitat utilisation, demographics, and management needs. SPECIES ACTION PLAN for Marine Turtles OBJECTIVES 1. Continue to monitor the status of nesting populations and ensure that they are protected from extirpation. 2. Determine the status of, and threats to, foraging populations. 3. Ensure the long-term stability of foraging populations. 4. Ensure sustained support for the conservation of Marine Turtles through targeted education and awareness programmes. TARGET ongoing ongoing ongoing ongoing

Marine Turtles PROPOSED ACTION Policy & Legislation PL1. Pass and implement the National Conservation Law. PL2. Enact Endangered Species (Trade & Transport) Law in order to fully transpose CITES into domestic law. PL3. Amend legislation to eliminate capture of mature Marine Turtles, through moratorium, extended closed season, or implementation of a maximum size limit. PL4. Mobilize volunteer support for nesting beach monitoring and expand volunteer programme. PL5. Develop and implement a monitoring system to ensure that legal Cayman Turtle Farm products can be differentiated from illegal products. PL6. Promote a mandatory policy of turtle friendly lighting and design for all new beachfront developments.

LEAD

PARTNERS

TARGET

MEETS OBJECTIVE 1,2,3,4 2,3 1,3

CIG DoE DoE

DoE CIG CIG

2006 2006 2006

PL3: REPORT: Legislation amended in 2008 to enact a maximum size limit and extended closed season. DoE DoE DoE VOL CTF MP CIG DoP CPA DCB ongoing ongoing 2012 1 2,4 1

Section: 3.M.3.1 Marine Species - Reptiles - Marine Turtles

Page: 3

Marine Turtles PROPOSED ACTION PL7. Promote a mandatory policy of native vegetation maintenance and/or landscaping for all new beachfront developments.

LEAD DoE

PARTNERS CIG DoP CPA DCB

TARGET 2012

MEETS OBJECTIVE 1

Safeguards & Management SM1. Using GIS data, ensure that key nesting habitats are protected from coastal development. SM2. Using GIS location data, ensure that key foraging habitats are protected. SM3. Mitigate the effects of inappropriate beach lighting by installing turtle-friendly lights in key locations. SM4. Implement associated HAPs. Advisory A1. Train Customs personnel in identification of marine turtle products. A2. Address marine debris and litter control issues. A3. Targeted awareness of the need for the National Conservation Law and the Endangered Species (Trade & Transport) Law. A3. REPORT: Extensive public outreach Mar-Sept 2010. Research & Monitoring RM1. Continue systematic monitoring efforts on nesting beaches on all three islands, in order to determine population trends towards informing conservation management. RM2. Conduct sustainable, regular, and frequent inwater monitoring on all three islands to determine trends in abundance of foraging populations, and identify key habitats towards informing conservation management. RM3. Analyse genetic structure of juvenile Green Turtle Chelonia mydas populations to determine contribution of Cayman Islands Turtle Farm to wild foraging aggregations. RM4. Construct Sister Islands research accommodation (Little Cayman) DoE MTRG MCB MTRG MTRG CTF IntC ongoing 1 DoE DoE DoE HMC CIG CIG CIG NT 2006 2008 2006 1,3 1,3 1,2,3,4 DoE DoE DoE DoE DOP DOP DoP MP 2008 2006 ongoing 2015 1 2,3 1 1,2,3,4

DoE

ongoing

2,3

DoE DoE

2010 2008

2 1,2,3

RM4. REPORT: Accommodation for up to four individuals on Little Cayman established by DoE, 2008. Communication & Publicity CP1. Targeted awareness campaign to key sectors of Government and local community. CP2. Maintain local and international media campaign. CP3. Launch educational DVD / schools packs. CP4. Promote island-wide awareness of the differences between adult and juvenile sea turtles through production of educational posters, fliers, and media releases. CP5. Expand sea turtle education in the National Curriculum. CP6. Raise public awareness of the ecological value of sandy beach and cobble using Marine Turtles as a flagship for preservation. CP7. Raise awareness of sustainable alternatives to threatened fisheries amongst members of the public through involvement with educational programmes e.g. Cayman Sea Sense CP8. Utilise native flora and fauna, and associated preservation efforts, in the international promotion of the Cayman Islands DoE DoE DoE DoE DoE DoE NT CIG CIG MP MP DE DE MP DE MP MP DoE DoT CA MP DoE MP NT DoT 2006 ongoing 2006 ongoing 2008 ongoing ongoing 2010 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4

Section: 3.M.3.1 Marine Species - Reptiles - Marine Turtles

Page: 4

References and Further Reading for Marine Turtles

Bell, C.D., Blumenthal, J.M., Broderick, A.C., Godley, B.J. (2009). Investigating potential for depensation in marine turtles: How low can you go? Conservation Biology, 24(1):226-235. Bell, C.D., Blumenthal, J.M., Austin, T.J., Ebanks-Petrie, G., Broderick, A.C., Godley, B.J. (2008). Harnessing recreational divers for the collection of sea turtle data around the Cayman Islands. Tourism in Marine Environments, 5(4): 245-257 Bell, C., Solomon, J.L., Blumenthal, J.M., Austin, T.J., Ebanks-Petrie, G., Broderick, A.C., Godley, BJ (2007). Monitoring and conservation of critically reduced marine turtle nesting populations: lessons from the Cayman Islands. Animal Conservation, 10:39-47 Bell, C.D., Blumenthal, J.M., Austin, T.J., Solomon, J.L., Ebanks-Petrie, G., Broderick A.C., Godley, B.J. (2006). Traditional Caymanian fishery may impede local marine turtle population recovery. Endangered Species Research 2, 63-69 Blumenthal, J.M., Solomon, J.L., Bell, C.D., Austin, T.J., Ebanks-Petrie, G., Coyne, M.S., Broderick, A.C., Godley, B.J. (2006). Satellite tracking highlights the need for international cooperation in marine turtle management. Endangered Species Research, 2: 51-61 Blumenthal, J.M., Austin, T.J., Bothwell, J.B., Broderick, A.C., Ebanks-Petrie, G., Olynik, J.R., Orr, M.F., Solomon, J.L., Witt, M.J., Godley, B.J. (2009). Diving behaviour and movements of juvenile hawksbill turtles Eretmochelys imbricata on a Caribbean coral reef. Coral Reefs, 28(55-65). Blumenthal, J.M. , Austin, T.J., Bell, C.D., Bothwell, J.B., Broderick, A.C., Ebanks-Petrie, G., Gibb, J.A., Luke, K.E., Olynik, J.R., Orr, M.F., Solomon, J.L., Godley, B.J. (2009). Ecology of hawksbill turtles Eretmochelys imbricata in a western Caribbean foraging area. Chelonian Conservation and Biology, 8:1-10 Blumenthal, J.M., Abreu-Grobois, A., Austin, T.J., Broderick, A.C., Bruford, M.W., Coyne, M.S., Ebanks-Petrie, G., Formia, A., Meylan, P.A., Meylan, A.B., Godley, B.J. (2010). Turtle groups or turtle soup: patterns of dispersal of hawksbill turtles in the Caribbean. Molecular Ecology, 18, 441-4853. Blumenthal, J.M., Austin, T.J, Bothwell, J.B., Broderick, A.C., Ebanks-Petrie, G., Olynik J.R., Orr, M.F., Solomon, J.L., Witt, M.J., Godley, B.J. (2010) Life in (and out of ) the lagoon: insights into movements of green turtles using time depth recorders. Aquatic Biology, 9: 113-121. Considine, J.L. (1973). Mariculture and the turtling industry of Grand Cayman: mans response to a vanishing resource. M.A. Thesis. Department of Geography, University of South Carolina. Duncan, D.D. (1943). Capturing giant turtle in the Caribbean. National Geographic Magazine, 84:177-190. Echternacht, A.C., Burton, F.J. and Blumenthal, J.M. (2011). The amphibians and reptiles of the Cayman Isands: Conservation issues in the face of invasions. pp. 129-147 in: Hailey, A.,B.S. Wilson and J.A. Horrocks, eds. Conservation of Caribbean Island Herpetofaunas, Vol. 1, Conservation Biology and the Wider Caribbean. Brill, Leiden. Wood, F.E. and Wood, J.R. (1994). Sea Turtles of the Cayman Islands. In: The Cayman Islands, natural history and biogeography. (eds M.A. Brunt and J.E. Davies), pp. 229-236. The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Section: 3.M.3.1 Marine Species - Reptiles - Marine Turtles

Page: 5

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Cayman Islands National Biodiversity Action Plan 2009 3.T.4.4 Terrestrial Species - Birds West Indian Whistling-DuckDocument5 pagesCayman Islands National Biodiversity Action Plan 2009 3.T.4.4 Terrestrial Species - Birds West Indian Whistling-Ducksnaip1370No ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Cayman Islands National Biodiversity Action Plan 2009 3.S.2.1 Coastal Species - Invertebrates White Land CrabDocument5 pagesCayman Islands National Biodiversity Action Plan 2009 3.S.2.1 Coastal Species - Invertebrates White Land Crabsnaip1370No ratings yet

- Cayman Islands National Biodiversity Action Plan 2009 3.T.4.6 Terrestrial Species - Birds Vitelline WarblerDocument5 pagesCayman Islands National Biodiversity Action Plan 2009 3.T.4.6 Terrestrial Species - Birds Vitelline Warblersnaip1370No ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- UntitledDocument9 pagesUntitledsnaip1370No ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Cayman Islands National Biodiversity Action Plan 2009 3.T.4.5 Terrestrial Species - Birds Cayman ParrotDocument7 pagesCayman Islands National Biodiversity Action Plan 2009 3.T.4.5 Terrestrial Species - Birds Cayman Parrotsnaip1370No ratings yet

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- UntitledDocument4 pagesUntitledsnaip1370No ratings yet

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Cayman Islands National Biodiversity Action Plan 2009 3.T.2.2 Terrestrial Species - Invertebrates Cayman Pygmy Blue ButterflyDocument4 pagesCayman Islands National Biodiversity Action Plan 2009 3.T.2.2 Terrestrial Species - Invertebrates Cayman Pygmy Blue Butterflysnaip1370No ratings yet

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Cayman Islands National Biodiversity Action Plan 2009 3.T.4.1 Terrestrial Species - Birds White-Tailed TropicbirdDocument4 pagesCayman Islands National Biodiversity Action Plan 2009 3.T.4.1 Terrestrial Species - Birds White-Tailed Tropicbirdsnaip1370No ratings yet

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Cayman Islands National Biodiversity Action Plan 2009 3.T.4.3 Terrestrial Species - Birds Brown BoobyDocument6 pagesCayman Islands National Biodiversity Action Plan 2009 3.T.4.3 Terrestrial Species - Birds Brown Boobysnaip1370No ratings yet

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- UntitledDocument7 pagesUntitledsnaip1370No ratings yet

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- UntitledDocument6 pagesUntitledsnaip1370No ratings yet

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- UntitledDocument4 pagesUntitledsnaip1370No ratings yet

- Cayman Islands National Biodiversity Action Plan 2009 3.T.4.2 Terrestrial Species - Birds Red-Footed BoobyDocument6 pagesCayman Islands National Biodiversity Action Plan 2009 3.T.4.2 Terrestrial Species - Birds Red-Footed Boobysnaip1370No ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- UntitledDocument4 pagesUntitledsnaip1370No ratings yet

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- UntitledDocument4 pagesUntitledsnaip1370No ratings yet

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Verbesina Caymanensis: Cayman Islands National Biodiversity Action Plan 2009 3.T.1.16 Terrestrial Species - PlantsDocument4 pagesVerbesina Caymanensis: Cayman Islands National Biodiversity Action Plan 2009 3.T.1.16 Terrestrial Species - Plantssnaip1370No ratings yet

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Cayman Islands National Biodiversity Action Plan 2009 3.T.2.1 Terrestrial Species - Invertebrates Little Cayman SnailDocument4 pagesCayman Islands National Biodiversity Action Plan 2009 3.T.2.1 Terrestrial Species - Invertebrates Little Cayman Snailsnaip1370No ratings yet

- UntitledDocument3 pagesUntitledsnaip1370No ratings yet

- Aegiphila Caymanensis: Cayman Islands National Biodiversity Action Plan 2009 3.T.1.13 Terrestrial Species - PlantsDocument4 pagesAegiphila Caymanensis: Cayman Islands National Biodiversity Action Plan 2009 3.T.1.13 Terrestrial Species - Plantssnaip1370No ratings yet

- Cayman Islands National Biodiversity Action Plan 2009 3.T.1.14 Terrestrial Species - Plants Cayman SageDocument4 pagesCayman Islands National Biodiversity Action Plan 2009 3.T.1.14 Terrestrial Species - Plants Cayman Sagesnaip1370No ratings yet

- Banara Caymanensis: Cayman Islands National Biodiversity Action Plan 2009 3.T.1.9 Terrestrial Species - PlantsDocument4 pagesBanara Caymanensis: Cayman Islands National Biodiversity Action Plan 2009 3.T.1.9 Terrestrial Species - Plantssnaip1370No ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Consolea Millspaughii CaymanensisDocument4 pagesConsolea Millspaughii Caymanensissnaip1370No ratings yet

- Cayman Islands National Biodiversity Action Plan 2009 3.T.1.11 Terrestrial Species - Plants CedarDocument5 pagesCayman Islands National Biodiversity Action Plan 2009 3.T.1.11 Terrestrial Species - Plants Cedarsnaip1370No ratings yet

- UntitledDocument4 pagesUntitledsnaip1370No ratings yet

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- UntitledDocument4 pagesUntitledsnaip1370No ratings yet

- Cayman Islands National Biodiversity Action Plan 2009 3.T.1.5 Terrestrial Species - Plants Ghost OrchidDocument5 pagesCayman Islands National Biodiversity Action Plan 2009 3.T.1.5 Terrestrial Species - Plants Ghost Orchidsnaip1370No ratings yet

- UntitledDocument4 pagesUntitledsnaip1370No ratings yet

- UntitledDocument4 pagesUntitledsnaip1370No ratings yet

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (120)

- UntitledDocument4 pagesUntitledsnaip1370No ratings yet

- Broadacre CityDocument8 pagesBroadacre CitySuresh Twanabasu A PositiveNo ratings yet

- Curriculum Vitae PDFDocument3 pagesCurriculum Vitae PDFKetutTomySuhariNo ratings yet

- CRAWFORD How To Create A Municipium Rome and Italy After The Social WarDocument17 pagesCRAWFORD How To Create A Municipium Rome and Italy After The Social WarPablo Varona Rubio100% (1)

- Dgca CPL SyllabusDocument26 pagesDgca CPL SyllabusasthNo ratings yet

- Physical Features of PakistanDocument29 pagesPhysical Features of PakistanAtif Malik100% (3)

- CdoDocument164 pagesCdodanrothenbergNo ratings yet

- Constructing A FAMOUS Ocean Model: Chris JonesDocument19 pagesConstructing A FAMOUS Ocean Model: Chris JonesPier Paolo Dal MonteNo ratings yet

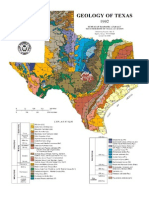

- Geologic Map of Texas, 1992Document2 pagesGeologic Map of Texas, 1992Steve DiverNo ratings yet

- Clarin Historical Background EtcDocument43 pagesClarin Historical Background EtcRjdewy DemandannteNo ratings yet

- Reading Comprehension TestDocument8 pagesReading Comprehension TestAzucena HayaNo ratings yet

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Measuring Urban Growth of Pune City Using Shanon Entropy ApproachDocument13 pagesMeasuring Urban Growth of Pune City Using Shanon Entropy ApproachÎsmaîl Îbrahîm SilêmanNo ratings yet

- 08 Eating India PDFDocument6 pages08 Eating India PDFJosé RemediNo ratings yet

- 11 - Chapter 4 PDFDocument37 pages11 - Chapter 4 PDFrNo ratings yet

- Geochemistry: Vegetation SurveysDocument26 pagesGeochemistry: Vegetation SurveysIfan AzizNo ratings yet

- RPH Lesson 2 3 and 4Document3 pagesRPH Lesson 2 3 and 4Angela AquinoNo ratings yet

- Terrestrial Plant Ecology: Third EditionDocument31 pagesTerrestrial Plant Ecology: Third EditiongandaNo ratings yet

- Elana Berlin Research ResumeDocument2 pagesElana Berlin Research Resumeapi-338583994No ratings yet

- Abban EK Et Al 2004Document63 pagesAbban EK Et Al 2004james_bilceNo ratings yet

- Manek ChowkDocument42 pagesManek ChowkRaj Agrawal100% (1)

- Princes Channel Wreck - Phase IIIDocument77 pagesPrinces Channel Wreck - Phase IIIWessex ArchaeologyNo ratings yet

- CP - KPK 2012Document120 pagesCP - KPK 2012Paki12345No ratings yet

- Geological MapsDocument209 pagesGeological Mapssaul saul100% (3)

- Land and Water Forms, Use and ManagementDocument11 pagesLand and Water Forms, Use and ManagementRolly Keth NabanalanNo ratings yet

- Point Comparison ReportDocument5 pagesPoint Comparison Reportpopovicib_2No ratings yet

- Topographic Map of Star MountainDocument1 pageTopographic Map of Star MountainHistoricalMaps100% (1)

- ARN Report 1006Document9 pagesARN Report 1006Larry ZeliskoNo ratings yet

- CD112-Philippine Waters PDFDocument2 pagesCD112-Philippine Waters PDFKaren Clyde PamaNo ratings yet

- Buena Mano Q3-2013 Greater Metro Manila Area CatalogDocument48 pagesBuena Mano Q3-2013 Greater Metro Manila Area CatalogJay CastilloNo ratings yet

- Bridges To Be Closed 2018-04-05Document2 pagesBridges To Be Closed 2018-04-05Sam HallNo ratings yet

- Tehri Garhwal PDFDocument25 pagesTehri Garhwal PDFsonal sonalNo ratings yet