Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Oil Price Shocks and Emerging Stock Markets: A Generalized Var Approach

Uploaded by

purnendumaityOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Oil Price Shocks and Emerging Stock Markets: A Generalized Var Approach

Uploaded by

purnendumaityCopyright:

Available Formats

International Journal of Applied Econometrics and Quantitative Studies . Vol.

1 -2(2004)

OIL PRICE SHOCKS AND EMERGING STOCK MARKETS: A GENERALIZED VAR APPROACH MAGHYEREH, Aktham* Abstract This study examines the dynamic linkages between crude oil price shocks and stock market returns in 22 emerging economies. The vector autoregression (VAR) analysis is carried on daily data for the period spanned from January 1, 1998 to April 31, 2004. This study utilized the generalized approach to forecast error variance decomposition and impulse response analysis in favor of the more traditional orthogonalized approach. Inconsistent with prior research on developed economies, the findings imply that oil shocks have no significant impact on stock index returns in emerging economies. The results also suggest that stock market returns in these economies do not rationally signal shocks in the crude oil market. JEL Classification: G10, G12. Keywords: Oil Prices, Emerging stock markets, VAR model.

1. Introduction

The oil price shock of 1973 and the subsequent recession give rise to a plethora of studies analyzing the interrelation between economic variables and oil price changes. The early studies include Pierce and Enzler (1974), Rasche and Tatom (1977), and Draby (1982), all of which documented and explained the inverse relationship between oil price increases and aggregate economic activity. Later empirical studies-such as, Hickman et al. (1987), Jones and Leiby (1996), Hooker (1999), Hammes and Wills (2003) and Leigh et al. (2003)-

Aktham Maghyereh is Assistant Dean at the Faculty of Economics and Business Administration, the Hashemite University, Jordan. E-mail: maghyreh@hu.edu.jo

27

Maghyereh, A.

Oil Price Shocks and Emerging Stock Markets

confirm the inverse relationship between oil prices and aggregate economic activity. Although the bulk of the empirical studies focus on the relation between economic activity and oil price changes, it is surprising that few studies have been conducted on the relationship between financial markets and oil price shocks- and those mainly for a few industrialized countries such as the United States, United Kingdom, Japan, and Canada. For example, Jones and Kaul (1992) examine the effect of oil prices on stock prices in the U.S. They find an effect of oil prices on aggregate real stock returns, including a lagged effect, in the period 1947 to 1991. In more recent study, Jones and Kaul (1996) test whether the reaction of international stock markets to oil shocks can be justified by current and future changes in real cash flows and/or changes in expected returns. They find that in the postwar period, the reaction of United States and Canadian stock prices to oil shocks can be completely accounted for by the impact of these shocks on real cash flows. In contrast, the results for both the United Kingdom and Japan are not as strong. In an important study, Haung et al. (1996) examine the link between daily oil future returns and daily U.S. stock returns. The evidence suggests that oil futures returns do lead some individual oil company stock returns but oil future returns do not have much impact on general market indices. Gjerde and Saettem (1999) demonstrate that stock returns have a positive and delayed response to changes in industrial production and that the stock market responds rationally to oil price changes in the Norwegian market. Sadorsky (1999) finds that oil prices play an important role in affecting real stock returns. Although all of these studies recognize the importance of causal relationships between oil prices and stock market returns in some industrial countries, the results from such studies cannot be generalized to other countries. Consequently, this paper extends the understanding on the dynamic relationship between oil prices and stock market return by using data from 22 emerging stock markets, which helps to fill in the gap. Specifically, this paper investigates the 28

International Journal of Applied Econometrics and Quantitative Studies . Vol.1 -2(2004)

dynamic interactions between crude oil prices and stock prices in a large sample of emerging economies. If oil plays a prominent role in an economy, one would expect changes in oil prices to be correlated with changes in stock prices. Specifically, it can be argued that if oil affects real economic activity, it will affect earnings of companies through which oil is a direct or indirect cost of operation. Thus, an increase in oil prices will cause expected earnings to decline, and this would bring about an immediate decrease in stock prices if the stock market effectively capitalizes the cash flow implications of the oil price increases. If the stock market is inefficient, stock returns might be slowly. Given the evidence of stronger linkages between crude oil prices and stock markets in developed economies, this study considers this issue in the emerging economies. The study examines the dynamic linkages between crude oil prices and stock market returns in many emerging economies and essentially asks two questions. To what extent are price changes or returns in crude oil market lead stock returns in emerging markets? How efficiently are innovations/shocks in crude oil market transmitted to the stock markets in the emerging economies? In answering these questions it is hoped that some light may shed on the importance of the crude oil on economic output in the emerging economies. The vector autoregression (VAR) technique that is employed in this study is well suited to answering these questions. The study utilized the generalized approach to forecast error variance decomposition and impulse response analysis in favor of the more traditional orthogonalized approach. The problem with the orthogonalized approach to variance decomposition and impulse response analysis is that the order of the variables in the VAR determines the outcome of the results. The generalized approach is invariant to the ordering of the variables in the VAR and produces one unique result.

29

Maghyereh, A.

Oil Price Shocks and Emerging Stock Markets

The paper proceeds as follows. Section 2 describes the data used in the paper. Section 3 provides an overview of the methodological issues. Section 4 presents the empiric al evidence. Section 5 provides some concluding remarks. 2. Data The stock market data in this paper are obtained from Morgan Stanley Capital International (MSCI). The sample is daily encompasses the period from 1 January 1998 to 31 April 2004 and contains U.S. dollar dominated value-weighted stock market indices for the following 22 emerging countries: Argentina, Brazil, Chile, China, Czech Republic, Egypt, Greece, India, Indonesia, Jordan, Korea, Malaysia, Mexico, Morocco, Hungary, Pakistan, Philippines, Poland, South Africa, Taiwan, Thailand, and Turkey. We choose to use the MSCI indices rather than other local stock price indices for several reasons. First, these indices are constructed on a consistent basis by the MSCI, making cross-country comparison more meaningful. Second, these indices are value-weighted reflects a substantial percentage of total market capitalization which could minimize the problem of autocorrelation in returns result from nonsynchronous trading. Third, MSCI indices are widely employed in the literature on the basis of the degree of comparability and avoidance of dual listing. The crude oil market is the largest commodity market in the world. Total world consumption equals around 80 million barrels a day in 2003. Prices of three types of oil- Brent, West Texas Intermediate and Dubai-serve as a benchmark for other types of crude oil. Processing costs and therefore prices of oil depend on two important characteristics: sulphur content and density. Oil that has a low sulphur content ("sweet") and a low density ("light") is cheaper than process than oil that has a high sulphur content ("sour") and high density ("heavy"). For instance the price of West Texas Intermediate is generally higher than Brent oil as it is sweeter and lighter than Brent oil. Of total world oil consumption of about 80 million barrels 30

International Journal of Applied Econometrics and Quantitative Studies . Vol.1 -2(2004)

a day in 2003, Brent oil serves as a benchmark for about 50 million barrels a day, West Texas Intermediate for about 15 million barrels a day and Dubai for about 15 million barrels a day. Even though price differences do exist, crude oil prices tend to move very closely together. Since Brent oil serves as a benchmark in the crude oil market, daily closing prices of crude oil Brent are used as our primary proxy for the world price of crude oil1 . The daily closing prices for crude oil Brent for the period from 1 January 1995 to 31 April 2004 are obtained from the U.S. Energy Information Administration. Finally, consistent with convention, all data used in this study has been transformed by taking the natural logarithm of the raw data. 3.- Methodology The unrestricted vector autoregression (VAR) approach used in this study was developed by Sims (1980). The VAR was developed to account for problems with intervention and transfer function analysis. This model provides a multivariate framework where changes in a particular variable are related to changes in its own lags and to changes in other variables. The VAR treats all variables as jointly endogeneous and imposes no a priori restrictions on the structural relationships, if any, between variables being analyzed. Because the VAR expresses the dependent variables in terms of only predetermined lagged variables, the VAR model is a reduced form model. An argument that naturally arises in the context of a VAR is whether one should use levels or first differences in the VAR. Clearly if the variable are I(0) processes this is not an issue. The difficultly arises, however, when the variables need to be differenced to get a stationary process, as they almost invariably do when dealing stock index data. Because of the information that is lost in

1

We also estimated the results using daily for Arab light, Arab Medium, Dubai and West Texas as alternatives for the world price of oil and found these measures did not substantively affect our results.

31

Maghyereh, A.

Oil Price Shocks and Emerging Stock Markets

differencing, Sims (1980) and Doan (1992) have argued against it. The majority view, highlighted by Granger and Newbold (1974) and Phillips (1986) is that stationary data should be used since nonstationary data can lead to spurious regression results. Further, Toda and Yamamoto (1995) noted that conventional asymptotic theory is, in general, not applicable to hypothesis testing in levels VARs if the variables are integrated, say I(1). Thus, as the first step, the order of integration of the variables is tested. Tests for the presence of a unit root based on the work of Dickey and Fuller (1979, 1981), Perron (1988), Phillips (1987), Phillips and Perron (1988) 2 , and Kwiatkowski et al. (1992) 3 are used to investigate the degree of integration of the variables used in the empirical analysis. If a I(1) process does exist, the second step involves estimation of the VAR model with first differences4 , otherwise VAR is estimated in levels. To determine the appropriate number of lag length of the VAR model, the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and Schwarz Bayesian Criterion (SBC) are employed.

This version of the test is an extension of the Dickey-Fuller test, which makes a semi-parametric correlation for autocorrelation and is more robust in the case of weakly autocorrelated and heteroskedastic regression residuals. 3 The KPSS procedure assumes the univariate series can be decomposed into the sum of a deterministic trend, random walk, and stationary I(0) disturbance and is based on a Lagrange Multiplier score testing principle. This test reverses the null and alternative hypothesis. A finding favorable to a unit root in this case requires strong evidence against the hypothesis of stationarity. 4 Earlier studies of stock returns have shown that stock returns exhibit a number of important seasonalities (e.g. January and week-end effects). These sesonalities are accounted for in our analysis by introducing dummy variables in the VAR model. Furthermore, important events in oil and equity markets during the period under investigation are the September 11th attacks and its subsequent and the U.S. invitation of Iraq on March 19. Oil and equity markets fluctuated dramatically as a consequence of these events, therefore these events are also accounted for in the analysis by introducing dummy variables.

32

International Journal of Applied Econometrics and Quantitative Studies . Vol.1 -2(2004)

Next, the generalized variance decomposition and generalized impulse response functions are employed to analysis the short-run dynamics of the variables. The purpose of the investigation is to find how each of emerging markets responds to shocks by the crude oil market. The forecast-error of generalized variance decomposition analysis reveals information about the proportion of the movements in market returns due to its own shocks versus shocks to the oil crude market. The dynamic responses of stock market to innovations in the crude oil market can also be traced out using the generalized impulse response analysis. Plotting the generalized impulse response functions is a particular way to explore the response of a stock market to a shock immediately or with various lags. Unlike t e h orthogonalized variance decomposition and impulse response functions obtained using the Choleskey factorization, the generalized variance decomposition and impulse response functions are unique solution and invariant to the ordering of the variables in the VAR (Koop et al. 1996; and Pesaran and Shin, 1998). Another argument that arises in the context of an unrestricted VAR is whether this model should be used where the variables in the VAR are cointegrated. There is a body of literature that supports the use of a vector error correction model (VECM), or cointegrating VAR if variables are integrated, I(1). Because the cointegrating vectors bind the long run behavior of the variables, the VECM is expected to produce results in the impulse response analysis and variance decomposition that more accurately reflect the relationship between the variables than the standard unrestricted VAR. It has been argued, however, that in the short run unrestricted VARs perform better than a cointegrating VAR (see for example, Naka and Tufte, 1997). Furthermore, Engle and Yoo (1987), Clements and Hendry (1995), and Hoffman and Rasche (1996) have shown that an unrestricted VAR is superior (in terms of forecast variance) to a restricted VECM at short horizons when the restriction is true. Naka and Tufte (1997) also studied the performance of VECMs and unrestricted VARs for impulse response analysis over the short-run and found that the performance of the two methods is 33

Maghyereh, A.

Oil Price Shocks and Emerging Stock Markets

nearly identical. This suggests that abandoning vector autoregressions for short horizon work is premature, especially when one considers their low computational burden. Although Johansen multivariate cointegration analysis is carried out in this study and cointegrating relationships founds, unrestricted VARs are used because of the short-term nature of the variance decomposition and impulse response analysis. 4. Empirical Results Table 1 presents the ADF, PP, and KPSS tests for the 21 stock markets indexes as well as crude oil price in levels and first differences. The results are consistent with what has been found in most of the previous literature using such types of data. Specifically, the three tests show that the logarithm of all series has a unit root, but the first differences are stationary. Given the importance of using stationary variables, these results necessitated the use of first differenced data to carry out the VAR analysis. As we mentioned above, the interpretation of the VAR model can brought to light through the generalized variance decomposition analysis and the estimation of the generalized impulse response functions. The results of variance decomposition are presented in Table 2. The reported numbers indicate the percentage of the forecast error in each stock market that can be attributed to innovations in the crude oil market at four different time horizons: one day, 5, 10 and 15-day ahead. The results of generalized variance decomposition analysis and generalized impulse response function provide the same conclusions regardless of order of decomposition since their estimation is independent of the ordering. The generalized decomposition tends to suggests that the crude oil price shocks have no significant impact on any of emerging stock market under investigation. Specifically, in all cases the crude oil shocks explain less than 2% of the forecast errors variances and in 16 of the 22 emerging markets this ratio falls to less than 1%.

34

International Journal of Applied Econometrics and Quantitative Studies . Vol.1 -2(2004)

Table 1. Unit Root Tests Variable Argentina Brazil China Czech Rep. Egypt Greece India Indonesia Jordan Korea Malaysia Mexico Morocco Hungary Pakistan Philippines Poland South Africa Taiwan Thailand Turkey Oil Price Critical Value 1% Critical Value 5% ADF -1.0 -1.3 -1.1 -1.5 -1.4 0.1 -1.0 -1.1 -1.4 2.1 -1.6 -2.2 -2.5 -1.7 -1.0 -0.4 -0.4 -1.1 -2.5 -1.7 -1.4 -0.9 -3.4 -2.9 Level PP -1.1 -1.3 -1.1 -1.4 -1.2 -0.1 -0.9 -1.0 -1.3 1.9 -1.6 -2.3 -2.5 -1.6 -0.9 -0.5 -0.5 -1.2 -2.4 -1.7 -1.4 -1.7 -3.4 -2.9 KPSS 2.9* 1.4* 1.4* 3.1* 3.5* 2.4* 3.1* 1.3* 1.8* 2.5* 0.8* 0.1 0.2 2.9* 2.7* 0.9* 1.7* 3.2* 1.6* 2.5* 0.9* 0.3** 0.7 0.5 First Difference ADF PP KPS S -16.1* -36.4* 0.3 -16.1* -30.5* 0.2 -13.5* -28.1* 0.3 -15.5* -32.5* 0.3 -15.1* -30.5* 0.4 -16.8* -33.5* 0.2 -14.6* -34.4* 0.6 -15.1* -31.5* 0.3 -15.8* -31.2* 0.3 -16.2* -34.8* 1.2 -16.4* -34.6* 0.1 -14.7* -30.8* 0.4 -16.8* -31.5* 0.1 -14.6* -30.7* 0.6 -15.2* -32.8* 0.8 -14.7* -34.3* 0.5 -14.7* -34.3* 0.3 -14.4* -30.1* 0.2 -16.1* -15.3* -15.1* -25.1* -3.4 -2.5 -30.8* -32.8* -34.1* -83.2* -3.4 -2.9 0.1 0.2 0.3 0.4 0.7 0.5

Notes: *and ** indicate statistical significant at the 1% and 5% level, respectively. The Augmented Dickey-Fuller (ADF) and the Phillips-Perron (PP) tested the null hypothesis of that the relevant series contains a unit root I(1) against the alternative that it does not, while the Kwiatowski-Pillips-Schmidt-Shin (KPSS) tested the null hypothesis that the series are I(0). The critical values for the ADF and PP are obtained from Dickey-Fuller (1981) while the KPSS critical values are obtained from Kwiatkowski et al. (1992).

35

Maghyereh, A.

Oil Price Shocks and Emerging Stock Markets

Table 2. Generalized decomposition of forecast error in emerging stock markets in response to shocks in the crude oil market (%) 5 days 10 days 15 days Argentina 0.622064 0.634352 0.641797 Brazil 0.181891 0.237485 0.255282 China 0.076167 0.053178 0.045921 Czech Republic 0.169356 0.245609 0.270753 Egypt 0.065641 0.086715 0.093538 Greece 1.146167 1.393299 1.546380 India 0.212965 0.731871 1.074984 Indonesia 0.014805 0.036561 0.049455 Jordan 0.172647 0.586863 0.855067 Korea 1.703050 2.020706 2.028246 Malaysia 1.375227 2.005126 2.384872 Mexico 0.042720 0.178622 0.261737 Morocco 0.022182 0.015533 0.012700 Hungary 0.117332 0.076421 0.059594 Pakistan 0.110283 0.272700 0.370517 Philippines 0.041558 0.036562 0.034073 Poland 0.041558 0.036562 0.034073 South Africa 1.130735 1.734103 2.051688 Taiwan 1.115818 1.353554 1.501680 Thailand 0.157792 0.530656 0.817114 Turkey 2.101294 2.381148 2.568307 Furthermore, the results show some interesting differences across countries in response to the oil market shocks, depending on the energy intensity of consumption and production. Specifically, the impact of oil shocks on stock m arket is highest in the largest Asian and Emerging Europe economies, as they have higher energy intensity consumption than most other emerging economies. For example, at the 15-day horizons, the percentage of error variance of a stock market explained by innovations in the crude oil market is 2.57 for Turkey followed by 2.38 for Malaysia. The Poland market appears to be the least influence by the oil market. 36

International Journal of Applied Econometrics and Quantitative Studies . Vol.1 -2(2004)

Turning to the question of how effectively innovations may transmit from the oil market to the emerging stock markets, Figure 1 plots the responses of each of the twenty two emerging stock markets to a one standard error shock in the oil market. The plots in Figure 1 show that innovations in the oil market are slowly transmitted in all of the emerging stock markets with markets responding to the oil shock two day after the shock. The speed with which the responses taper off to zero after the initial shock is felt for the most markets on day 4. Only six markets namely: Argentina, Brazil, China, Czech Republic Egypt and Greece, responses continuous until day 7. These results may indicate that the emerging markets are inefficient in transmitting innovations/shocks in the oil market. The inefficiency in responses to a shock in the oil market is also reflected in the inaccuracy of the initial response, to the shock. However, the small size of the responses (between 0.00051 to 0.00126, on day 2) reflecting that the oil market is very weak in influencing stock markets in emerging economies. 5.- Conclusion This study examines the dynamic linkages between oil price shocks and stock market returns in 22 emerging economies. Vector autoregression (VAR) analysis is carried on daily data for the period, January 1, 1998 to April 31, 2004. This study utilized the generalized approach to forecast error variance decomposition and impulse response analysis in favor of the more traditional orthogonalized approach. Inconsistent with the pervious empirical studies in developed economies, the results from the variance decomposition analysis provided very weak evidence that there is a relationship between the crude oil price shocks and stock market returns in the emerging economies. Furthermore, the results from impulse analysis reveal that innovations in the oil market are slowly transmitted in the emerging stock markets. These results suggest that stock markets in the emerging economies are inefficient in transmission of new information of the oil market. These results may also indicate that the importance of oil price for the aggregate economy, especially in 37

Maghyereh, A.

Oil Price Shocks and Emerging Stock Markets

emerging economies, is greatly over-estimated. These results may also suggest that the stock market returns in the emerging economies do not rationally signal changes in the crude oil prices. REFERENCES Clements, M.P. and D.F. Hendry, 1995, "Forecasting in Cointegrated System," Journal of Applied Econometrics, 10, 127-146. Darby, M. R., 1982, "The Price of Oil and World Inflation and Recession," American Economic Review, 72, 738-751. Dickey, D., W.A. Fulle r, 1979, "Distribution of the Estimates for Autoregressive Time Series with a Unit Root," Journal of the American Statistical Association, 74, 427-0431. Dickey, D., W.A. Fuller, 1981, "Likelihood Ratio Statistics for Autoregressive Time Series with a Unit Root," Econometrica, 49, 1057-1072. Doan, T. 1992, RATS User's Manual, Evanston III: Estima. Engle, R.F. and B.S. Yoo, 1987, "Forecasting and Testing in Cointegrated Systems," Journal of Econometrics, 35, 143-159. Granger, C.W.J and P. Newbold, 1994, "Spurious Regressions in Econometrics," Journal of Econometrics, 2, 111-120. Hammes, D. and D. Wills, 2003, Black Gold: The End of Bretton Woods and the Oil Price Shocks of the 1970s, Working Paper, University of Hawaii Hilo. Hickman, B., H. Huntington, and J. Sweeney, 1987, Macroeconomic Impacts of Energy Shocks, Amsterdam: north-Holland. Hoffman, D.L. and R.H. Rasche, 1996, "Assessing Forecast Performance in a Cointegrated System," Journal of Applied Econometrics, 11, 495-517. 38

International Journal of Applied Econometrics and Quantitative Studies . Vol.1 -2(2004)

Hooker, M. 1999, "Are O Shocks Inflationary? Asymmetric and il Nonlinear Specifications versus Changes in Regime," Working Paper, Federal Reserve Board of Governors. Huang, R. D., R. W. Masulis, and H. R. Stoll, 1996, "Energy Shocks and Financial Markets," 27. The Journal of Future Markets, 16, 1-25. Jones, C. M. and G. Kaul, 1992, "Oil and Stock Markets," Journal of Finance, 51, 463-491. Jones, C. M. and G. Kaul, 1992, "Oil and Stock Markets," Working Paper, University of Michigan. Jones, D. W. and P. Leiby, 1996, "The Macroeconomic Impacts of Oil Price Shocks: A review of the Literature and Issues," Working Paper, Oak Ridge National Laboratory. Kwiatkowski, D., P.C.B. Phillips, P. Schmidt, and Y. Shim, 1992, "Testing the Null Hypothesis of Stationarity Against the Alternative of a Unit Root," Journal of Econometrics, 54, 159-178. Leigh, A., J. Wolfers, and E. Zitzewitz, 2003, "What do financial Markets Think about the War of Iraq?" Working Paper, Stanford Graduate School of Business. Naka, A. and D. Tufte, 1997, "Examining Impulse Response Functions in Cointegrated Systems," Applied Economics, 29, 15931603. Perron, P., 1988, "Trends and Random Walks in Macroeconomic Time: Series Further Evidence from a New Approach," Journal of Economic Dynamic and Control, 12, 297-332. Phillips, P.C.B. and P. Perron, 1988, "Testing for a Unit Root in Time Series regression," Biometrika, 75, 335-346.

39

Maghyereh, A.

Oil Price Shocks and Emerging Stock Markets

Phillips, P.C.B., 1986, "Understanding Spurious Regressions in Econometrics," Journal of Econometrics, 33, 311-340. Phillips, P.C.B., 1987, "Time Series Regression with a Unit Root," Econometrica, 55, 277-347. Pierce J. L., and J. E. Jared, 1974, "the Effects of External Inflationary Shocks," Brooking Papers on Economic Activity, 1, 13-61. Rasche, R. H., and J. A. Tatom, 1977, "The effect of the New energy Regime on Economic Capacity, Production and Prices," Economic Review, 59, 2-12. Sadorsky, P., 1999, "Oil Price Shocks and Stock Market Activity," Energy Economics, 21, 449-469. Sims, C. A., 1980, "Macroeconomics and reality," Econometrica, 48, 1-48. Toda, B.H. and T. Yamanoto, 1995, "Statistical Inference in Vector Autoregressions with Possibly Int.

____________________

Journal IJAEQS published by AEEADE: http://www.usc.es/economet/eaa.htm

40

You might also like

- Quality Standards For ECCE INDIA PDFDocument41 pagesQuality Standards For ECCE INDIA PDFMaryam Ben100% (4)

- Bring Your Gear 2010: Safely, Easily and in StyleDocument76 pagesBring Your Gear 2010: Safely, Easily and in StyleAkoumpakoula TampaoulatoumpaNo ratings yet

- Management Accounting by Cabrera Solution Manual 2011 PDFDocument3 pagesManagement Accounting by Cabrera Solution Manual 2011 PDFClaudette Clemente100% (1)

- Oil Prices ShokDocument23 pagesOil Prices ShokMoh SennNo ratings yet

- Does Oil Price Matter For Indian Stock Markets?: Munich Personal Repec ArchiveDocument14 pagesDoes Oil Price Matter For Indian Stock Markets?: Munich Personal Repec Archiveshabarisha nNo ratings yet

- Effects of Crude Oil Price Changes On Sector Indices of Istanbul Stock ExchangeDocument16 pagesEffects of Crude Oil Price Changes On Sector Indices of Istanbul Stock Exchangenakarani39No ratings yet

- Research Proposal: Changes in Oil Prices and Their Impact On Emerging Markets ReturnsDocument11 pagesResearch Proposal: Changes in Oil Prices and Their Impact On Emerging Markets ReturnsMehran Arshad100% (1)

- Thouraya Amor - FinalDocument24 pagesThouraya Amor - FinalLoulou DePanamNo ratings yet

- Adeniyi PaperDocument29 pagesAdeniyi PaperIjezie EbukaNo ratings yet

- Paper VolatilityTransmissionDocument23 pagesPaper VolatilityTransmissionandaleebrNo ratings yet

- 9483-Article Text-35986-1-10-20151222 PDFDocument12 pages9483-Article Text-35986-1-10-20151222 PDFrajatiaNo ratings yet

- Co-Movement of Oil Price, Exchange Rate and Stock Index of Major Oil Importing Countries: A Wavelet Coherence ApproachDocument19 pagesCo-Movement of Oil Price, Exchange Rate and Stock Index of Major Oil Importing Countries: A Wavelet Coherence ApproachR. Shyaam PrasadhNo ratings yet

- Nonlinear Linkages Between Oil and Stock Markets in Developed and Emerging CountriesDocument14 pagesNonlinear Linkages Between Oil and Stock Markets in Developed and Emerging CountriesKamran AfzalNo ratings yet

- The Interaction Between Oil Price and Economic GrowthDocument16 pagesThe Interaction Between Oil Price and Economic GrowthKamranNo ratings yet

- Oil Prices and Stock Markets: What Drives What in The Gulf Corporation Council Countries?Document20 pagesOil Prices and Stock Markets: What Drives What in The Gulf Corporation Council Countries?fasizakNo ratings yet

- Determinants of Oil Price As On 6-2-2016Document17 pagesDeterminants of Oil Price As On 6-2-2016R. Shyaam PrasadhNo ratings yet

- Comovements and Volatility Spillovers Between Oil Prices and Stock Markets: Further Evidence For Oil-Exporting and Oil-Importing CountriesDocument12 pagesComovements and Volatility Spillovers Between Oil Prices and Stock Markets: Further Evidence For Oil-Exporting and Oil-Importing CountriesNATIQNo ratings yet

- Cause & Effect Research PaperDocument4 pagesCause & Effect Research PaperKashif Ahmed SaeedNo ratings yet

- Futures Markets, Commodity Prices and The Intertemporal Approach To The Current AccountDocument47 pagesFutures Markets, Commodity Prices and The Intertemporal Approach To The Current Accountscorpion2001glaNo ratings yet

- Return and Volatility Transmission Between World Oil Prices and Stock Markets of The GCC CountriesDocument24 pagesReturn and Volatility Transmission Between World Oil Prices and Stock Markets of The GCC CountriesPalwasha MalikNo ratings yet

- The Changing Effects of Oil Price Changes On Inflation: Adviser: Professor Bwo-Nung HuangDocument68 pagesThe Changing Effects of Oil Price Changes On Inflation: Adviser: Professor Bwo-Nung HuangAin NsfNo ratings yet

- 02 Rafay and Farid FINALDocument14 pages02 Rafay and Farid FINALShahid MushtaqNo ratings yet

- Oil Prices DynamicsDocument28 pagesOil Prices DynamicsVishesh DwivediNo ratings yet

- Computational Modeling of Crude Oil Price PDFDocument13 pagesComputational Modeling of Crude Oil Price PDFMisLibrosNo ratings yet

- Volatility Transmission in The Oil and Natural Gas Markets: Bradley T. Ewing, Farooq Malik, Ozkan OzfidanDocument14 pagesVolatility Transmission in The Oil and Natural Gas Markets: Bradley T. Ewing, Farooq Malik, Ozkan OzfidanAnum Nadeem GillNo ratings yet

- Investigating The Asymmetric Impact of Oil Prices On GCC Stock MarketsDocument41 pagesInvestigating The Asymmetric Impact of Oil Prices On GCC Stock MarketsNacNo ratings yet

- Oil Price Shocks and Stock Markets in Brics: The European Journal of Comparative Economics Vol. 8, N. 1, Pp. 29-45Document17 pagesOil Price Shocks and Stock Markets in Brics: The European Journal of Comparative Economics Vol. 8, N. 1, Pp. 29-45Kamran AfzalNo ratings yet

- Oil Prices and Stock Market Price in NigeriaDocument17 pagesOil Prices and Stock Market Price in NigeriaThomas ThomasNo ratings yet

- Oil Prices and Stock Market Price in NigeriaDocument17 pagesOil Prices and Stock Market Price in NigeriaThomas ThomasNo ratings yet

- The Stock Market Reaction To Oil Price ChangesDocument35 pagesThe Stock Market Reaction To Oil Price ChangesVincent FongNo ratings yet

- Yip Chee YinDocument9 pagesYip Chee YinSuhaila IbrahimNo ratings yet

- Crude Oil - End Product Linkages in The European Petroleum MarketsDocument18 pagesCrude Oil - End Product Linkages in The European Petroleum MarketslenoelmNo ratings yet

- The Effects of Oil Price On Asia - Pacific Exchange Rates: Evidence From Quantile Regression AnalysisDocument11 pagesThe Effects of Oil Price On Asia - Pacific Exchange Rates: Evidence From Quantile Regression AnalysisNonton BersamaNo ratings yet

- How Does Stock Market Volatility React To Oil Price ShocksDocument28 pagesHow Does Stock Market Volatility React To Oil Price ShocksMariem Ben AmorNo ratings yet

- 2016 Liu Et Al Disentangling Determint Real Oil PricesDocument11 pages2016 Liu Et Al Disentangling Determint Real Oil PricesBlasNo ratings yet

- Physical Market Determinants of The Price of Crude Oil and The Market PremiumDocument23 pagesPhysical Market Determinants of The Price of Crude Oil and The Market PremiumGabrielaMSNo ratings yet

- Oil Price Determinants and Co-Movement Dynamics: Synopsis ofDocument16 pagesOil Price Determinants and Co-Movement Dynamics: Synopsis ofR. Shyaam PrasadhNo ratings yet

- 27-Crude Oil Price ChangesDocument12 pages27-Crude Oil Price ChangesMuhammad TohamyNo ratings yet

- Rangkuman 5 JurnalDocument2 pagesRangkuman 5 JurnalDeksa FebriaNo ratings yet

- Jadmin, FulltextDocument18 pagesJadmin, Fulltextnour nciriNo ratings yet

- OPEC and Demand Response To Crude Oil PricesDocument30 pagesOPEC and Demand Response To Crude Oil PricesMartín E. Rodríguez AmiamaNo ratings yet

- Allegret, J.P., Mignon, V. and Sallenave, A., 2015. Oil Price Shocks and Global Imbalances Lessons From A Model With Trade and Financial Interdependencies. Economic Modelling, 49, pp.232-247 PDFDocument33 pagesAllegret, J.P., Mignon, V. and Sallenave, A., 2015. Oil Price Shocks and Global Imbalances Lessons From A Model With Trade and Financial Interdependencies. Economic Modelling, 49, pp.232-247 PDFChan Hui Yan YanNo ratings yet

- Impacts of Oil Price Shocks On The U.S. Economy: A Meta-Analysis of Oil Price Elasticity of GDP For Net Oil-Importing EconomiesDocument2 pagesImpacts of Oil Price Shocks On The U.S. Economy: A Meta-Analysis of Oil Price Elasticity of GDP For Net Oil-Importing EconomiesCliffhangerNo ratings yet

- 187paper 1Document8 pages187paper 1ZUNERAKHALIDNo ratings yet

- Amano Et Al-1998-Review of International EconomicsDocument12 pagesAmano Et Al-1998-Review of International EconomicsHaseen Ahmed JRF, Centre for Management StudiesNo ratings yet

- Mean RevDocument44 pagesMean RevLameuneNo ratings yet

- Energy Economics: Lin Zhao, Xun Zhang, Shouyang Wang, Shanying XuDocument10 pagesEnergy Economics: Lin Zhao, Xun Zhang, Shouyang Wang, Shanying XuTarun RahejaNo ratings yet

- WPS1 3DF5CBC6Document27 pagesWPS1 3DF5CBC6IFS IESNo ratings yet

- Mini Proj Synopsis 1Document5 pagesMini Proj Synopsis 1Adarsh ArunNo ratings yet

- 2019 - The Role of CAPM and Oil Prices To Analyze The Firms Stock ReturnDocument12 pages2019 - The Role of CAPM and Oil Prices To Analyze The Firms Stock ReturnMuqaddas KhalidNo ratings yet

- The Links Between The Price of Oil and The Value of US DollarDocument11 pagesThe Links Between The Price of Oil and The Value of US Dollarkinhtequocte41No ratings yet

- Oil Price Elasticities and Oil Price Fluctuations: International Finance Discussion PapersDocument60 pagesOil Price Elasticities and Oil Price Fluctuations: International Finance Discussion PapersprdyumnNo ratings yet

- Research ReportDocument13 pagesResearch ReportShahroz AslamNo ratings yet

- Bataa Osborn SampleDocument23 pagesBataa Osborn SampleMyagmarsuren BoldbaatarNo ratings yet

- Energy Economics: Dayong ZhangDocument11 pagesEnergy Economics: Dayong ZhangAnum Nadeem GillNo ratings yet

- The Effects of Oil Price Shocks On Asian Exchange Rates Evidence From Quantile Regression AnalysisDocument20 pagesThe Effects of Oil Price Shocks On Asian Exchange Rates Evidence From Quantile Regression AnalysisHospital BasisNo ratings yet

- A World Equilibrium Model of The Oil MarketDocument57 pagesA World Equilibrium Model of The Oil MarketBhoomikaNo ratings yet

- REVISITING The Oil Price and Stock Market Nexus - A NARDL PDFDocument14 pagesREVISITING The Oil Price and Stock Market Nexus - A NARDL PDFsayari hediNo ratings yet

- What Is An Oil ShockDocument72 pagesWhat Is An Oil ShockAlzaraniNo ratings yet

- SING17-The Effect of Speculation in Futures Market On Oil Price-Extended Abstract-RevisedDocument2 pagesSING17-The Effect of Speculation in Futures Market On Oil Price-Extended Abstract-Revisedlagopatis4No ratings yet

- Intro N SummaryDocument21 pagesIntro N SummaryKannan RiseeNo ratings yet

- The Future of India IT and ITeS IndustryDocument54 pagesThe Future of India IT and ITeS IndustrypurnendumaityNo ratings yet

- Oil Price Shocks and Stock ReturnsDocument77 pagesOil Price Shocks and Stock ReturnspurnendumaityNo ratings yet

- Who Are My Best CustomersDocument12 pagesWho Are My Best CustomerspurnendumaityNo ratings yet

- The Ifrs Taxonomy 2011 Guide: March 2011Document72 pagesThe Ifrs Taxonomy 2011 Guide: March 2011purnendumaityNo ratings yet

- CDS Default ProbabilityDocument32 pagesCDS Default ProbabilitypurnendumaityNo ratings yet

- McKinsey 2006 January TentrendsDocument4 pagesMcKinsey 2006 January TentrendspurnendumaityNo ratings yet

- "Europe As A Challenge - Challenges To Europe": Series of Lectures On "Europe in Transition" - Fall 2007Document38 pages"Europe As A Challenge - Challenges To Europe": Series of Lectures On "Europe in Transition" - Fall 2007purnendumaityNo ratings yet

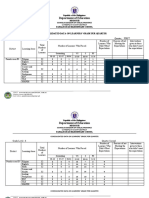

- Department of Education: Consolidated Data On Learners' Grade Per QuarterDocument4 pagesDepartment of Education: Consolidated Data On Learners' Grade Per QuarterUsagi HamadaNo ratings yet

- Etag 002 PT 2 PDFDocument13 pagesEtag 002 PT 2 PDFRui RibeiroNo ratings yet

- Code of Ethics For Civil Engineers PiceDocument3 pagesCode of Ethics For Civil Engineers PiceEdwin Ramos Policarpio100% (3)

- Documentation Report On School's Direction SettingDocument24 pagesDocumentation Report On School's Direction SettingSheila May FielNo ratings yet

- Hitachi Vehicle CardDocument44 pagesHitachi Vehicle CardKieran RyanNo ratings yet

- Importance of Porosity - Permeability Relationship in Sandstone Petrophysical PropertiesDocument61 pagesImportance of Porosity - Permeability Relationship in Sandstone Petrophysical PropertiesjrtnNo ratings yet

- SSC Gr8 Biotech Q4 Module 1 WK 1 - v.01-CC-released-09May2021Document22 pagesSSC Gr8 Biotech Q4 Module 1 WK 1 - v.01-CC-released-09May2021Ivy JeanneNo ratings yet

- Template Budget ProposalDocument4 pagesTemplate Budget ProposalimamNo ratings yet

- Daftar ObatDocument18 pagesDaftar Obatyuyun hanakoNo ratings yet

- Arudha PDFDocument17 pagesArudha PDFRakesh Singh100% (1)

- BECED S4 Motivational Techniques PDFDocument11 pagesBECED S4 Motivational Techniques PDFAmeil OrindayNo ratings yet

- Service Quality Dimensions of A Philippine State UDocument10 pagesService Quality Dimensions of A Philippine State UVilma SottoNo ratings yet

- Javascript Notes For ProfessionalsDocument490 pagesJavascript Notes For ProfessionalsDragos Stefan NeaguNo ratings yet

- MATM1534 Main Exam 2022 PDFDocument7 pagesMATM1534 Main Exam 2022 PDFGiftNo ratings yet

- Stress Management HandoutsDocument3 pagesStress Management HandoutsUsha SharmaNo ratings yet

- Cash Flow July 2021Document25 pagesCash Flow July 2021pratima jadhavNo ratings yet

- Does Adding Salt To Water Makes It Boil FasterDocument1 pageDoes Adding Salt To Water Makes It Boil Fasterfelixcouture2007No ratings yet

- Work Energy Power SlidesDocument36 pagesWork Energy Power Slidessweehian844100% (1)

- Banking Ombudsman 58Document4 pagesBanking Ombudsman 58Sahil GauravNo ratings yet

- CHAPTER 2 Part2 csc159Document26 pagesCHAPTER 2 Part2 csc159Wan Syazwan ImanNo ratings yet

- Applications of Wireless Sensor Networks: An Up-to-Date SurveyDocument24 pagesApplications of Wireless Sensor Networks: An Up-to-Date SurveyFranco Di NataleNo ratings yet

- Ficha Técnica Panel Solar 590W LuxenDocument2 pagesFicha Técnica Panel Solar 590W LuxenyolmarcfNo ratings yet

- Hyundai SL760Document203 pagesHyundai SL760Anonymous yjK3peI7100% (3)

- Sony x300 ManualDocument8 pagesSony x300 ManualMarcosCanforaNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Job DescriptionDocument13 pagesJurnal Job DescriptionAji Mulia PrasNo ratings yet

- CM2192 - High Performance Liquid Chromatography For Rapid Separation and Analysis of A Vitamin C TabletDocument2 pagesCM2192 - High Performance Liquid Chromatography For Rapid Separation and Analysis of A Vitamin C TabletJames HookNo ratings yet