Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Finley 1969

Uploaded by

Sultan AkgünOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Finley 1969

Uploaded by

Sultan AkgünCopyright:

Available Formats

1969: BLACK ART AND THE

AESTHETICS OF MEMORY

Cheryl FINLEY Cornell University Nineteen-sixty-nine marked a seminal year of the Black Arts Movement (1965-1976). Beginning on January ninth, the Black Emergency Cultural Coalition (B.E.C.C.), led by artists Benny Andrews and Henri Ghent, was formed to protest the absence of black artistic, curatorial and scholarly participation in the exhibition, Harlem on My Mind: Cultural Capitol of Black America, 1900-1968. That divisive show, on view at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York from January 18th to April 6th of that year, was organized by Allon Schoener and boycotted by black artists for its failure to include works by contemporary black artists or to involve black curators or arts professionals. Recognized as the first ever blockbuster exhibition in the United States, the failings of Harlem on My Mind ignited local and national controversy and its aftermath served to bring to a boil an already simmering pot of black artistic activism against the exclusionary practices of mainstream cultural institutions around the country. The year ended with the founding of a new black arts institution, Cinque Gallery, in December 1969 by artists Romare Bearden, Ernest Crichlow and Norman Lewis in New Yorks East Village. Named for the heroic leader of the famed 1839 Amistad revolt, Cinque Gallery operated as a not-for-profit representing the work of young, emerging black artists. With a name chosen from black history, the aims and purposes of Cinque

CHERYL FINLEY

Gallery and the artists it showed had a mission and consciousness rooted in the black struggle that the patronizing and popular Harlem on My Mind did not have. These two events serve as bookends to a prolific and indeed pivotal year of black creativity, bringing into sharper view an arsenal of images, establishment of practices and awareness of attitudes that would be used by black artists to define black art and identity in America for years to come. To be sure, the Black Arts Movement was the most significant black creative arts explosion since the Harlem Renaissance (1919-1929). Known for the formation of artists collectives, culturally-focused institutions and community-based programming, the Black Arts Movement represented a period of intense artistic, social and political activism that grew out of the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s and valued its focus on education. The Black Arts Movement furthermore mirrored the Black Power struggle of the 1960s and early 1970s and tapped into black international freedom struggles in Africa, the Caribbean and Europe (England and France) of the same period. Encompassing the visual, literary and performing arts, the Black Arts Movement produced a racially focused art that explored the roots and meanings of black identity during an era of black self-determination. As Mary Schmidt Campbell observed, In the face of the extraordinary political and social changes brought about by the Civil Rights Movement, many Black American artists found it necessary to clear away the old symbols of the ancien regime and put in their place new metaphors for a new African American identity, an identity that would permanently supplant the Negro in American culture (Schmidt Campbell, 1985, 64). For some artists, this meant re-working racist stereotypes from the past in order to render them impotent and strip them of their demeaning powers. For example, the sexless, brooding servant embodied by the Aunt Jemima stereotype was parodied with grenade in hand in Joe Overstreets larger-than-life pancake box called New Jemima (1964), and revolutionized by Betye Saar, with a rifle and the clinched Black Power fist in The Liberation of Aunt Jemima (1972). But for other artists, this meant remembering empowering icons and noted figures in black history to shape new works of art that define identity in social, political, economic and gendered perspectives. As Schmidt Campbell explains, the remembering clarified the distinctiveness of African American history (Schmidt Campbell, 1985, 65). In a purposeful, aesthetic process that I have called symbolic possession of the past, these artists have found it

1969

necessary to reach back in time to reclaim important emblems and icons of history as a way of understanding their relationship to the present (Finley 2001). Practicing a form of mnemonic aesthetics, they reinterpret the symbols of the past in order to bring into focus the uniqueness of black history, identity and culture, indeed to define their ongoing struggle to be in America. The Black Arts Movement heralded a time of revolutionary art production and dissemination, where black artists employed innovative and radical means to create, publish and exhibit their work. Its greatest proponents utilized new materials, such as acrylic paint, synthetic polymers, and unstructured canvases as well as clever means of presenting ideas, such as Revolutionary Theatre, performance art and photography. They frequently relied upon the symbols of the past as fodder for their works of activist potential. 1. Soul Searching One of the key images that black artists resurrected during this period of soul searching was an eighteenth century abolitionist icon: a black and white schematic print showing, in the words of its original maker, the Plymouth Committee of the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade (SEAST) in England, a Plan of an African Ships lower deck with Negroes in the Proportion of only one to a Ton (fig. 1). That shocking image was first published in 1789 as an oblong engraving accompanying a four-page pamphlet calling for the end of the slave trade. It was later incorporated into broadsides, tracts and material objects of varying designs and effectiveness and distributed by the thousands by the London Committee of the SEAST and other abolitionist committees in England, France and the United States over the next 20 years (Fig. 3). Even after the slave trade was legally abolished by the United Kingdom and the United States in 1807 and 1808 respectively, the poignancy of the plan of the slave ship continued to resonate among crusaders against the burgeoning illegal slave trade and the daily brutalities of slavery on New World sugar, cotton and tobacco plantations.i The plan of the slave ship remained an icon, a revolutionary print in the abolitionists arsenal, until chattel slavery as a system of human bondage was brought to an end. I have named that image the slave ship icon for its continued presence in the minds and creative work of twentieth century black artists and their allies (Finley 1999).

CHERYL FINLEY

For black artists, playwrights and poets of the 1960s, the slave ship icon was pregnant with multiple, useful interpretations, adaptable for Black Nationalist and integrationist agendas alike. One of the most influential publications responsible for developing mid-twentieth century black consciousness of the slave ship icon, and forging a purposeful remembering of that influential image, was A Pictorial History of the Negro in America: 1,000 Illustrations from Prints, Engravings, Photographs, Paintings written by Langston Hughes and Milton Meltzer in 1956. Published just two years after the historic Brown vs. Board of Education Supreme Court decision that declared segregation illegal, that book was a rallying cry for black people to wake up and reclaim the images that had shaped their past. A Pictorial History of the Negro in America provided visual fodder for the Black Arts Movement in the form of historical images meticulously selected from the collections of Hughes and Meltzer as well as archives from around the country. As the books promotional material claimed, This book is far more than a collection of pictures fascinating as they are. Beginning with the origins of the Negro in Africa, the authors trace in text and picture the story of the Negro as a slave and as a freeman, who he is, where he came from, what he has contributed, how he has affected and, in turn, has been affected by American life and, finally, where his is headed. Included in this absorbing account are reproductions of news editorials, letters, posters, handbills and pamphlets, ranging from the early days of the slave trade to the recent desegregation decision of the Supreme Court (Hughes & Meltzer, 1956, book jacket flap). Accompanying the profusely illustrated pages was a moving text written by Hughes, which led the reader/viewer to the significance of each image in black history. The Hughes-Meltzer collaboration was reminiscent of earlier fruitful partnerships that produced notable photographically illustrated books with integrated and inspiring narratives. Distinguished among these are Richard Wright and Edwin Rosskams Twelve Million Black Voices (1941) and Hughess own joint venture with photographer Roy De Carava, The Sweet Flypaper of Life (1955). A Pictorial History of the Negro in America also owed a debt of gratitude to other historical precursors, including the journals Opportunity, Crisis, Negro Digest and the Journal of Negro History. Together, the momentum started by these pioneering black history and culture journals, the Hughes-Meltzer collaboration, and the appearance of popular black-oriented magazines like Jet and Ebony set the

1969

stage for all manner of educational advances in African American Studies in the 1960s and 1970s, including the reissuing of important black authored texts from the 1920s and 1930s; the establishment of black studies departments in mainstream American colleges and universities; and the integration of black history as part of secondary and elementary school curricula.ii The first book of its kind to be published after the Brown vs. Board of Education decision, A Pictorial History of the Negro in America made a direct link between the value of knowing ones history and the success of freedom struggles: Here, for the first time, is an authoritative, panoramic picture story of the Negro in America, from the arrival of the first African slave ship to present times, covering every aspect of Negro life social, political, artistic and economic. This unique book, lavishly illustrated with more than 1,000 reproductions of pictures, paintings, broadsides, drawings, woodcuts and cartoons, contains concise pictorial accounts of all the important events in the Negros dramatic struggle for freedom (Hughes & Meltzer, 1956, book jacket flap). A Pictorial History of the Negro in America moreover inspired an entire cadre of black artists and writers in the 1960s and 1970s, including Alex Haley (Roots, 1976); black artists collectives, such as the Organization of Black American Culture (OBAC), that spearheaded the public mural movement of the late 1960s with the Wall of Respect (1967) in Chicago; the poet and playwright Amiri Baraka (formerly Le Roi Jones); and the artist Malcolm Bailey. By remembering and presenting visual images and documents from the past, this volume clarified the distinctiveness of African American history (Schmidt Campbell, 1985, 65). A Pictorial History of the Negro in America was thus one of the key progenitors of the black visual practice of remembering known as symbolic possession of the past. And the slave ship icon was one of its essential images. In the pages that follow, I discuss two seminal works that were produced in 1969 in which artists reintroduced and reinterpreted the slave ship icon: Amiri Barakas masterpiece of Revolutionary Theatre, Slave Ship: A Historical Pageant and Malcolm Baileys Separate but Equal series. These celebrated works of theatre and installation art are representative of a novel artistic practice that hinges on the relationship between history, memory and identity.

CHERYL FINLEY

2. Amiri Baraka and the Development of Revolutionary Theatre Amiri Baraka was the chief artist-intellectual of the Black Arts Movement. Through his critically acclaimed poems, plays, jazz operas and music criticism, he encouraged black artists to abandon the integrationist themes of a raceless, classless society, which had become popular in the previous decade, to instead embrace an art and practice that was grounded in black experience, history and memory. In Barakas own words, the Black Arts Movement declared a need for:

1. An art that is recognizably Afro American 2. An art that is mass oriented that will come out of the libraries and stomp 3. An art that is revolutionary, that will be with Malcolm X and Rob Williams, that will conk klansmen and erase racists (Baraka in Harris, 1991, xxi). Espousing an ideology of black cultural nationalism, Baraka asserted that black art was a means for black artists and their audiences to gain deeper understanding of themselves.1 This was especially so during the decade spanning from 1965 to 1974 when Barakas poetry, theatre and Black Arts Movement manifestos were concerned with developing an aesthetic strategy for deflecting, overcoming and eliminating centuries of racism embedded in American society.

Nineteen sixty four was indeed Barakas single most important year in theatre, wherein he wrote, published and had produced five one act plays including The Baptism, The Toilet, Dutchman, The Slave, and The Eighth Ditch. As Hughes and Meltzer remarked in Black Magic: A Pictorial History of the Negro in American Entertainment, During the 1964 season Jones became the most talked about dramatist in New York when he had five plays performed one after the other in four different houses. Each of his dramas depicted the moral and spiritual decay of the United States. All these five one1

In 1974, Baraka rejected Black Nationalism and converted to a form of international socialism, which he calls Third World Marxism.(Harris, 1991, xii xxxii).

1969

acters attracted such attention pro and con that two of them were closed by orders of the police (Hughes & Meltzer, 1967, 251)2 Among the three plays that were not shuttered down, Dutchman, presented at the Cherry Lane Theatre in Greenwich Village, was the biggest hit, winning Baraka an Obie Award and securing for him serious critical consideration from the American theatre establishment. By 1965, Baraka moved uptown to Harlem, where he founded the Black Arts Repertory Theatre, refusing admittance to whites for productions that were performed by black actors for exclusively black audiences. Notable among these were Experimental Death Unit #1 (1965), a parody of Samuel Beckets Waiting for Godot, and J-E-L-L-O (1966), a satire of the popular television program, the Jack Benny Show. As Werner Sollors explains, Barakas satires of white culture, high and popular, were attempts to reach and de-brainwash Black audiences from a Black nationalist point of view (Sollors, 1978, 205). As Baraka explained about the Black Arts Repertory Theatre, We knew beyond our theories that we were correct, that we meant National Liberation, the liberation of a nation in bondage. We went up town to Harlem and opened a theatre, and blew a billion words into the firmament like black prayers to force change (Baraka, 1969c, 112). The Black Arts Repertory Theatre was shut down in spring 1966 when New York police claimed to have found a cache of weapons, but by then Baraka had abandoned the project and retreated to his native Newark, New Jersey, where he still lives today. There he established Spirit House, which continued to produce plays, such as Madheart (1966) and Great Goodness of Life (1966), for primarily black audiences, while honing the principles and practice of Revolutionary Theatre.

The two plays that were closed include The Eighth Ditch, about a homosexual rape in an army tent, presented by the Poets Theatre in early March 1964 and performed at the New Bowery Theatre, and The Baptism presented at the Writers Stage Theatre about black priest and an interracial congregation with sexual overtones including a chorus of pregnant virgins.

CHERYL FINLEY

Seeking an activist mode of expression for black art, Baraka pioneered a new form of black aesthetics, which he called Revolutionary Theatre.3 According to him, The Revolutionary Theatre should force change; it should be change (Baraka, 1966, 210). For Baraka, Revolutionary Theatre was inextricably linked to the political aims of the Black Power Movement and, as one of the most social of the performing arts, it could be an integral part of the Movements socializing process. In his words, Black Theatre has gotta gotta gotta raise the dead, and move the living (Baraka,1969c, 115). The activist dimension of Revolutionary Theatre demanded the involvement and action of audience members and thus was designed to conjure up responsibility and awareness through process and participation.

The political implications of Barakas Revolutionary Theatre, like environmental theatre of avant-garde New York in the 1960s and 1970s and the burgeoning performance art scene of the same period, involved a profound restructuring of the social and psychological relationships that exist between performer and audience, according to theatre critic Dan Isaac (Isaac, 1971, 242). As he explains, The fluidity of environmental theater encourages new social configurations. As a commercial entertainment, environmental theater simulates political action rather than necessarily initiating it (Isaac,1971, 245). Barakas notion of Revolutionary Theatre, however, also produced a ritual component encouraged by its participatory nature, which reinforced the social processes of remembering for actors and audience members alike. Intended to stimulate collective remembering, collective consciousness and collective action, Revolutionary Theatre, according to Baraka, called for new kinds of heroes ready to die for whats on their minds, and the portrayal of hidden histories as a way to gain control of the dissemination and interpretation of black images (Baraka, 1966, 214). Bringing political and contemporary urgency to pressing historical and social issues, such as police brutality and public school bussing, Revolutionary Theatre aimed to be a radical, artistic intervention directed towards dislocating the white mainstream manipulation of black images and experiences. As Sollors describes, Historical and

3

Baraka described Revolutionary Theatre as the forceof twenty million spooks storming America with furious cries and unstoppable weaponspeopled with new kinds of heroes ready to die for whats on their minds Baraka, 1966, 214-215).

1969

heroic plays established a past dimension to present struggles and confrontations (Sollors, 1978, 205). In addition to the familial narrative of black history and struggle going back several generations told to him by his father and grandfather around the kitchen table when he was growing up, the evolution of Barakas dramaturgy and political consciousness was also influenced by the repercussions of the assassination of Malcolm X and the Watts Riots in 1965, Barakas own repeated mistreatment at the hands of the New York City and Newark police as well as his own traumatic experience of the 1967 Newark Riots. That Revolutionary Theatre comes perhaps as a byproduct of these collective memories and experiences is not surprising to say the least. Indeed, for Baraka, Revolutionary Theatre was a theatre that challenged accepted practices and demanded change. 3. Slave Ship: A Historical Pageant Peace, Slave Ship do your thing was the closing line of Clive Barness otherwise scathing review of LeRoi Joness Slave Ship: A Historical Pageant, performed at the Brooklyn Academy of Musics Harvey Theatre from November 21, 1969 to January 13, 1970 (Barnes, 1969, 46).4 Produced by the Chelsea Theatre Centre in association with

4

The first production of Slave Ship was directed by LeRoi Jones at Spirit House in Newark, New Jersey and ran from March 1967 to an undetermined closing date receiving little, if any, critical attention. A community-based theatre arts center established by Jones in 1966 in an old warehouse in Joness home town, Spirit House and its production company, the Sprit House Movers, were modeled after Joness communitybased Black Arts Repertory Theatre, which produced plays, concerts and poetry readings with black subject matter for the education and cultural awakening of the Black People in America and for exclusively black audiences in the streets of Harlem, New York from spring 1965 to spring 1966, when it was forced to close. The Black Arts Repertory Theatre was financed with federal funds through the HARYOU Act and the Office of Economic Opportunity. The poets Yusef Iman and Ed Spriggs, the musicians Pharaoh Saunders and Sun Ra, and playwrights Ben Caldwell and Ed Bullins were associated with Spirit House early on. Jihad was the publishing house founded by Baraka associated with Spirit House.

10

CHERYL FINLEY

Woodie King, Jr., Slave Ship was directed by Gilbert Moses of the Free Southern Theater, who also composed the music along with tenor saxophonist Archie Shepp. Eugene Lee designed the unforgettable set, a wooden slave ship on rockers with an exposed human cargo hold, after drawings he had seen of the slave ship icon (Fig. 2). Subtitled a historical pageant, Jones meant for Slave Ship to be a shocking spectacle of historical tableaux, recreating in ceremonial fashion the progression of black history from Africa to America in a montage of visceral iconic scenes that all took place within or atop the ingenious slave ship set design. Beginning in Africa with ritual dance and rites of passage, the play progressed through the terror of the Middle Passage, the separation of families on the auction block, a plantation uprising foiled by a duplicitous Uncle Tom figure, and climaxed in a riot symbolizing the victory of black power over white America. Slave Ship immersed the audience in a total atmosfeeling, as Barakas script demanded, flashing the images, sounds and smells of black history in rapid-fire succession, producing a momentum forceful enough to mobilize a revolutionary call to action for supporters of the Black Arts Movement, or in Barakas words, to raise the dead, and move the living. And Slave Ship, no doubt, did its thing. As Isaac recalled, The best examples of [environmental theater] in recent New York seasons were Slave Ship and Stomp. Much more than mere entertainment, both works were constantly threatening to overflow the traditional boundaries of theatrical form by mobilizing an audience and urging them toward some action. (Isaac, 1971, 245). The artistic implications of setting of the entire play within the hold of a slave ship are our immediate concern. That radical choice recognized the centrality of the slave ship as a space of mnemonic proportions in the black psyche. When asked by television talk show host David Frost on January 5, 1969, What did you write the play [Slave Ship] to get across, in fact? Baraka responded, Well, to try to explain naturally to sensitive people, black people, exactly what the realities of the slave ship were and how they have carried over, how America in a lot of sense is just a reply or a continuation of that same slave ship, that its not changed (Hudson, 1981, 172). The play relied upon a novel set design, clever staging techniques and innovative props to produce and sustain the feeling of being trapped in the slave ship. As set designer Eugene Lee recalls,

1969

11

Jones Ship is a metaphor, a symbol, connecting the memory of African roots with the vicious containment of the present. The ship is the fulcrum from which the play moves both backward and forward in time. Gill Moses staged the piece in a very free form theatrical style, action occurred throughout the room (Schevill, 1973, 266).

Claiming the slave ship as the central metaphor or symbol necessarily dictated that the other spaces of black experience depicted in the play the plantation, insurrection, church, and culminating celebration of black power even were to be read through the defining experience of the Middle Passage and imagined from within the decks of the slave ship. Moreover, through the explicit strategies of Revolutionary Theatre, Barakas play not only attempted to embody the chaotic situation described by the slave ship icon, but it also succeeded in bringing it to life in a very tangible way that tapped into the sensorial dimension of memory of actors and audience members alike. Such a deliberate symbolic possession of the past recovered the political possibilities of the abolitionist-era slave ship icon, adding a new and meaningful layer of understanding for a late 1960s race-conscious black revolutionary audience. Let me take a moment to explain.

As a theatrical performance that took place in the symbolic space of the slave ship, the play, its set and improvisational staging referenced the visual appearance of the slave ship icon and the text used to describe it. On a visual level, the set shared certain architectural similarities with the space (or lack thereof) illustrated in the seven numbered plan and cross-section views of slave ship icon. Designed to reproduce the feeling of claustrophobia between decks, the creaky wooden set included hatches, platforms, masts and other architectural details represented in the plan of the slave ship. The set also produced a sense of confinement, which was amplified by the extreme contrast between complete and total darkness below decks and blinding sunlight above, suggesting the tension between black and white. Slave Ship, moreover, created the stifling, claustrophobic environment that the diagrammatic abolitionist drawing portrayed by producing the actual bodies that it depicted. The actors and audience members crammed together gave real, live physical form to tiny black figures meticulously drawn in the plan of the slave ship. But instead of

12

CHERYL FINLEY

remaining still or silent, Barakas slave bodies were allowed to speak and move about. Through them, he inserted the voices, desires, movements and music of resistance that were absent from the static, two-dimensional drawing of the slave ship icon. In a bold gesture then, Baraka re-inscribed the slave ship icon with an updated purpose fitting of the revolutionary times.

Barakas Slave Ship was closer to a reenactment of the experiences of the Middle Passage, plantation slavery and revolution, rather than a dramatic production of those events. As Revolutionary Theatre, audience members were an intimate and integral part of the play. They were seated on planks around the set that placed them in the deepest bowels of the slave ship, which moreover co-opted them as members of the cast, or re-enactors, if you will. In fact, in the script, they are listed among the cast as the voices and bodies in the slave ship (Baraka, 1969a, 1). The other members of the cast included the voices of African slaves, dancers, musicians, children, an Old Tom, played by a slave, and a New Tom, played by a preacher, in addition to the voices of white men, a captain, sailor and plantation owner.

Audience members were called upon to join the actors in making the sounds that created the aural setting for the play the cries and screams. By soliciting the participation of audience members to fill space and create sound, the sense of claustrophobia and terror in the hold of the slave ship was vividly and memorably reproduced by the action of the play.. Art historian Robert Farris Thompson, who attended (and participated in) three consecutive nights of performances of Slave Ship in 1969, recalled how the architectural rendering of the set, stage and seating produced a sense of being inside of the space that the slave ship icon depicts (Finley, 2001).This enabled members of the audience to share in the creation of the performance and consequently, moved them towards a sense of collective responsibility. As Francis Ngaboh-Smart points out, Baraka assumes that the ritual of the stage consists in situating the events in the hearts of the black audience who, after reliving the memory of the sources of their cultural dislocation, can then work towards remedying their condition.The collective enactment is supposed to help the community move toward regeneration (NgabohSmart, 1999,181-182). As a participatory event then, Slave Ship operated for many as a cathartic experience: one of confinement, passage, struggle and release.

1969

13

The play was set in a virtual theatre of the senses, a performance space invaded by the sights, sounds and smells used by abolitionists to describe the poo poo tubs, whips, chains, and cries. These dramatic effects were realized through the use of innovative props that stimulated the aural and olfactory perception, including:

Smell effectsincense dirt/filth Smells/bodies

Heavy Chains

Drums (African bata drums, and bass and snare) Rattles and tambourines Banjo music for plantation atmos. [sic]

Ship noises Ship bells Rocking and Splashing of Sea

Guns and cartridges

Whips/whip sounds (Baraka, 1969a, 1)

The effects of the sounds and smells emanating from the set of the slave ship were intensified by carefully controlling the sense of sight. In particular, darkness deep, total, consuming darkness was utilized in a sustained manner to emphasize the atmosphere of containment experienced during the Middle Passage and throughout slavery in order to enforce the feeling of domination. The initial stage directions called for:

14

CHERYL FINLEY

Whole theater in darkness. Dark. For a long time. Just Dark. Occasional sound, like ship groaning, squeaking, rocking. Sea smells. In the dark. Keep the people in the dark, and gradually the odors of the sea, the sounds of the sea, and sounds of the ship, creep up. Burn incense, but make a significant, almost stifling, smell come up. Urine. Excrement. Death. These smells and cries, the slash and tear of the lash, in a total atmos-feeling [sic] gotten some way (Baraka, 1969a, 1).

A large part of the play was, in fact, performed in darkness, producing and reproducing the drone of terror (Baraka, 1969a,1). Barakas use of lighting was specific and intentional. In some cases dim lights pointed to voices or spoken dialogue, There is just dim light at top of the set, to indicate where voices are (Baraka, 1969a ,2). In other instances, bright lights starkly illuminated the characters of the slave traders and sailors or and reproduced the effect of blinding sunlight coming from open hatches above deck. The stage directions specify, for example, Lights flash on white men in sailor suits grinning their vicesvoices down hummmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmm mmmmmmm. Lights to light white people are sudden, very bright and blinding (Baraka, 1969a, 5). As I have tried to suggest, Barakas play recovered and re-inscribed the slave ship icon, effectively reshaping the descriptive text of the eighteenth century broadside to include the voices of the enslaved and their stories of pain and suffering as well as their tactics of resistance and survival. For example, their accounts of suicide and infanticide are enacted here:

Man 1 God, shes killed herself and the chi (sic) child. Oh, God. Oh, God. Woman 1 She strangled herself with the chain. Choked the child. Oh, shango! Help us, Lord. Oh, please (Baraka, 1969a, 5).

1969

15

The well-documented history of rape and sexual abuse pictured and discussed in the schematic drawing and explanatory text of slave ship icon is also enacted in play:

Woman 2 Oh, please, please dont touch me Please Man 1 What you doing? Get away from that woman. Thats not your woman. You turn into a beast, too (Baraka, 1969a, 6). And insanity: Man 3 Devils, Devils. Cold walking shit. (All mad sounds together.) (Baraka, 1969a, 6)

With a dialogue that imagined the conversations between captives in the hold, Baraka created characters and stage directions that reflected a deep, spiritual belief in African, particularly Yoruba, religion. Some of the initial stage directions called for, African Drums like the worship of some Orisha. Obatala, Mbwanga rattles of the priests. BamBamBamBamBoom BoomBoom BamBam (Baraka, 1969a, 1). During the Middle Passage sequence, Shango, the Yoruba thunder god, and Obtl, the Yoruba creator god, father of the orishas or deities, are called upon as sources of strength through the ritual beating of drums.

Man 1 -

Shango, Obatala, make your lightning, beat the inside bright with paths for your people. Beat. Beat. Beat (Drums come up, but they are walls and floors being beaten. Chains rattled. Chains rattled. Drag the chains) (Baraka, 1969a, 3).

Towards the end of the play, the plantation revolt is brought on by summoning Ogun, the warrior god of iron.

Ogun. Give me weapons. Give me iron. My spear. My bone and muscle make them tight with tension of combat. Ogun, give me fire and death to give to these beasts (Baraka, 1969a, 3).

16

CHERYL FINLEY

According to Genevieve Fabre, [Slave Ship] retrouve aussi le fondement mythique qui sanctionne son lien avec la religion et lui permet de matriser la fois une inquitante et fbrile agitation et le vagabondage drgl de limagination artistque et du rve apollinien (Fabre, 1983, 120).

To be sure, Slave Ship wasnt alone in its attempt to practice a form of spiritual renaissance. Beginning in the 1950s with the surge of African liberation movements on the continent, there was a renewed sense of pride in Africa on the part of black Americans, who shared an interest in African languages, religions, customs and beliefs. Several artists, writers, historians and musicians journeyed to Africa to experience the revolutionary fervor of these seminal independence movements. Richard Wright traveled to the Gold Coast in 1953, now present day Ghana, to observe Kwame Nkrumahs rise to power as the first Prime Minister of that country, elected in 1957. Subsequently, a number of artists and writers associated with the Black Arts Movement, including the illustrator Tom Feelings, the writer Maya Angelou, and the political activists Malcolm X and Martin Luther King, Jr. traveled to Ghana, some staying on for years as expatriates and teachers. Amiri Baraka, along with the dancer Katherine Dunham, Langston Hughes and others, participated in the First World Festival of Negro Arts, organized by President Leopold Senghor in Dakar, Senegal in 1966.

Indeed, a committed interest in African spirituality and naming was a major tenet and legacy of the Black Arts Movement. A greater emphasis on black history and culture in education saw the inclusion of black studies curricula in grade schools and colleges and universities for the first time beginning in the late 1960s. Several black poets and writers changed their American names to African names, including, of course, Amiri Baraka (formerly LeRoi Jones); Haki Madhubuti (formerly Don Lee); and Muhammad Ali (formerly Cassius Clay), to name just a few. Moreover, some organizations of

1969

17

black artists named their groups after Swahili names, such as Weusi.

Slave Ship also relied upon improvisational music as a catalyst for action in the play. Baraka enlisted the talents of Sun Ra, known for his experimental electronic music, and tenor saxophonist Archie Shepp, among others. Repeated sounds and musical rifts acted as strips of behavior, ritual beats that called upon actors and audience participants to remember. Thus, African music and religion performed a life sustaining function, delivering the enslaved Africans from the slave ship to the plantation and, ultimately to the brink of a black nationalist revolution: The following last lines of the script are first chanted and then put to music:

Rise, Rise, Rise Cut these ties, Black man rise We gon be the thing we are (Now all sing, When we gonna Rise) When we gonna rise/up When we gonna rise/up When we gonna rise/up When we gonna rise/up, brother When we gonna rise/up above the sun When we gonna take our own place, brother Like the world had just begun?

Drum new sax voice arrangement (Baraka, 1969a, 13-14).

Throughout the play, drumming, dancing and music stand as symbols of resistance, and deep African memory. As the play opens, the sound of African drums dominate, whereas the plantation scene begins with the lazy sound of the banjo, but later crescendos with a drum call to revolt. In his seminal text on black music, Blues People, Baraka claimed that

18

CHERYL FINLEY

music presented itself as one of the most important legacies of the African past, even to the contemporary black American (Baraka, 1963, 123). Hughes and Meltzer also trace this musical legacy back to the continent of Africa through the Middle Passage and on to the plantation: The White sailors on the Middle Passage found these Africans and their rhythms highly entertaining, as did the planter ashore who purchased black imports to work on their American plantations. The syncopated beat which the captive Africans brought with them and which perhaps lightened a little of the burden of their servitude quickly took root in the New World. Now that beat has been for generations a basic part of American musical entertainment (Hughes & Meltzer, 1967, 3). Throughout the play, the musical symbols of an African past are never silenced, but only transformed, reshaped into popular forms of black American music. The culminating celebration of Black Power is punctuated by a fusion of jazz, soul music and popular black dances of the late 1960s:

Lights come up abruptly, and people on stage begin to dance, same hip Boogaloruba, fingerpop, skate, monkey, dog Enter audience; get members of audience to dance. To same music Rise Up. Turns into an actual party (Baraka, 1969a,16).

In Slave Ship, Baraka crafted a unique blend of double voicing that was richly nuanced, where the different layers of the senses and the spatial levels of the set collided and conversed with the actual voices of the cast and the audience, their co-opted re-enactors. This process of shaping and reshaping the experience of black Americans prompted Lloyd W. Brown to call Slave Ship one of Barakas more successful experiments in ritual drama, where history itself becomes a succession of rituals (Brown, 1980, 161).

4. Malcolm Bailey: Separate but Equal In the same year that Baraka produced Slave Ship, the young artist, Malcolm Bailey, gained widespread critical acclaim for his Separate But Equal series, an installation of monumental paintings and drawings inspired by the slave ship icon and the ensuing Civil Rights struggle. The series was featured in the inaugural exhibition of Cinque Gallery in

1969

19

New Yorks East Village in December 1969, where the 24 year-old artist created an arresting installation environment with life-size, black and white crouching figures painted in uniform rows across the gallery walls. A seven by four foot mixed media painting, Hold: Separate But Equal, showed more black and white figures contorted and prone within the confines of the cross section and plan of a slave ship in the manner of the famous British abolitionist engraving that began circulating the black Atlantic some 180 years before in 1789 (Figs. 3 & 5). By all measures, the exhibition was a huge success. Hold: Separate But Equal was selected for the 1970 Whitney Annual devoted to painting and subsequently purchased by the Museum of Modern Art. The exhibition struck a corporeal chord of mnemonic proportions, with some visitors pausing in the gallery to contort their own bodies into the fetal or rigor mortis-like poses of Baileys painted figures.

The founding of Cinque Gallery was just one indication of how visual artists shaped the Black Arts Movement. They formed artist collectives, opened art museums and galleries and lobbied mainstream arts institutions for greater representation of black artists, curators and programming. This period produced a black art geared to reach the masses through community-based mural projects and the establishment of neighborhood art centers in urban areas. Using art for political and educational purposes, black artists endeavored to portray black history and black life, often through the depiction of key events and individuals. To be sure, the Black Arts Movement promoted an art and ideology of Black Unity, Black Dignity and Black Respect.

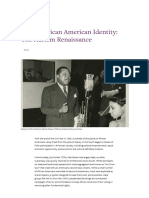

Malcolm Bailey was an early recipient of the advances won by the Civil Rights Movement. Born in Harlem in 1947, he won a fellowship to attend an integrated private secondary school before going on to study art at the High School of Art and Design in New York and Pratt Institute in Brooklyn. Bailey also received residencies at the predominantly white artist communities of Yaddo in Silver Springs, New York and the McDowell Colony in Peterborough, New Hampshire (Honig Fine, 1973, 62). He came to the attention of the mainstream art world largely through the Cinque Gallery premiere of his Separate But Equal series in 1969. In a photograph of the artist taken in front of one of his mural size paintings at Cinque gallery, he appeared poised for success (Fig. 4). Dressed in all black and sporting a neatly trimmed Afro, moustache and tinted glasses, Bailey was the vision of a cool and

20

CHERYL FINLEY

thriving downtown artist, and with good reason. Reviews of his work in the New York Times and elsewhere brought him immediate media attention and with that, sales of his work to prominent collectors and museums. Yet a reexamination of the photograph of Bailey at Cinque gallery, with his body mimicking the doubled-over slave figures, offers perhaps a reminder of the tenuous position that he, in fact, occupied in the art world, despite his successes. For, as Elton C. Fax remarked in his seminal collection Seventeen Black Artists, the gifted twenty-fouryear-old Malcolm Bailey, with all his merit, would not easily have found a place to show (Fax, 1971, 144).

Hold: Separate but Equal is an aqua blue panel with three schematic diagrams after the slave ship icon. Remarkably, the black and white male figures painted in the diagrams are divided by "race," not gender: on one side, white figures mirror an equal number of black figures on the other. The diagram on the left shows one side of a plan view. It is empty except for the capital letters that label the vacant spaces: G, A and E in black and N, B, F in white. The diagram on the right pictures the plan view of the half deck with two rows of uniform black figures systematically arranged on one side and the same number of white figures on the other. This section is labeled with the letter H in black at the top, and the letter E in white at the bottom. The diagram in the center shows a cross section view of the hold, with an equal number of black and white figures separated by a bold vertical line at center that represents the mast. The figures on the upper deck bend into contorted, seated positions in order to fit into the shallow space. Each of the figures is labeled with a letter (A, B and so on) that corresponds to a location specified on the plan views above. The artist drew black and white contour lines to define the musculature of these figures doubledover in distress. Such a clever use of shading rendered the figures as anatomical drawings. The black and white figures in the lower deck are allotted even less space and are reduced to a reclining position with legs bent. Instead of being labeled with single letters, this diagram is marked HOLD in bold, black letters in the white section of the boat.

Baileys choice of materials influenced the look and design of this painting. He applied synthetic polymer paint to composition board in order to achieve a slick aqua background. Press type was used to demarcate the hard lines of the diagrams and the fine, white directional lines that divide spaces within the sections. Press type also labeled the

1969

21

sections with bold, uniform letters. Art historian Kellie Jones has pointed out how some of the exciting new materials of the space age, such as acrylic paint, synthetic polymers and mixed media, were utilized black abstract artists to achieve revolutionary effects (Jones, 2006, 17). Together, these materials lent a crisp, mechanical look to the painting that reduced it to its barest essentials and enhanced its minimalist, blueprint appearance. The use of a minimalist aesthetic accentuated the starkness of the plan view on the left and gave the sense that the other sections werent quite filled to capacity. This visual strategy revealed a clear contrast between many of the late-eighteenth century drawings of slave ship plans made by abolitionists, which were filled to capacity with tiny figures to emphasize overcrowding and inhumane conditions onboard. With its apparent sense of openness and attention to spatial dynamics, Baileys blue print-like painting conjures up larger questions of freedom and equality for the races.

Hold: Separate But Equal clearly engaged the popular national debate over integration that came to a head at the end of the 1960s with the emergence of the Black Power Movement, which fought vigorously for black nationalism. By now, it should be obvious that the title, Separate But Equal, refers to the landmark school desegregation case, Brown vs. Board of Education, argued by Thurgood Marshall before the Supreme Court in 1954, which overturned Plessy vs. Ferguson, the 1896 ruling that amounted to government-sanctioned segregation and created the doctrine of separate but equal for blacks and whites.5 The triumph of Brown vs. Board of Education marked a turning point for the Civil Rights Movement and ushered in greater government control over the integration of public facilities, public schools and government workplaces.

At the pinnacle of the Black Arts and Black Power Movements, Bailey created a series that visually engaged the national debate over integration and racial equality. He did so by placing white figures

5

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 introduced the separate but equal doctrine in public transportation not education. Nevertheless, separate but equal was applied to all areas of black civil rights in the United States, especially in the area of education in the South.

22

CHERYL FINLEY

alongside black figures in a minimalist reiteration of the slave ship icon to draw connections between a long history of suffering and racial strife and the political urgency that characterized the contemporary moment: race riots, assassinations, and anti-war demonstrations alongside black student protests, and the establishment of black cultural institutions. As Bailey put it in an interview with Elsa Honig Fine in 1972, real revolution wont occur until poor whites as well as poor blacks realize they are oppressed (Honig Fine, 1973, 272). His iconic black and white figures were a visual affirmation of that ideology: they mirror and double each other, duplicating the same painful postures of the continuing race/class divide. 5. Coda: A Theology of Remembrance On December 17, 2000 a circular stained glass window with an image of the slave ship icon was dedicated at the New Mount Pilgrim Missionary Baptist Church, a black congregation in the West Garfield Park neighborhood of Chicago (Fig. 6). The brilliant rose window stands 25 in diameter on the east side of the building. The morning sunlight illuminates the somber shades of blue and gray that color the central figure: an African man with outstretched arms whose torso is filled with the central crowded section of the slave ship icon. With chains descending from his outstretched arms and angular pieces of stained glass that depict currents of water, he seems to be pushing up, propelling his body through the water, rising from the depths of an unspeakable struggle. It would be hard not to mistake the body of this African man as a Christ figure, albeit one that has been updated for an African American audience poised to take control of the images that align their historic struggle with those of biblical narratives. According to the Rev. Marshall E. Hatch, pastor of the New Mount Pilgrim Missionary Baptist Church, Thats a Christ figure for us, an African Man. Hes ascending with the bodies and suffering of the slave ship (Walters, 2000, 24). The idea for the window was inspired by a drawing in the illustrated book, Middle Passage: White Ships, Black Cargo by Tom Feelings, which caught the attention of The Rev. Hatch while he was a scholar-in-residence at the Harvard Divinity School in 1998 (Feelings, 1995). Since its publication in 1995, Feelings book has remained hugely popular with black audiences in the United States, an accessible visual narrative that depicts a formative part of collective black experience in easy to read, yet excruciatingly visceral images. In all, the book has 54 pen and ink tempera drawings with an introduction by John Henrick Clarke. Feelings purposely chose not to include a written narrative, with the idea

1969

23

that the images would tell the story, while allowing the reader/viewers to imagine an accompanying text. Feelings, a native of Brooklyn, New York, studied painting at the School of Visual Arts in Manhattan in the mid-1950s. After a stint in the Air Force, he moved to Ghana in 1964, where he taught art for several years. Upon his return to New York in the early 1970s, he aligned himself with the Black Arts Movement and began to illustrate Afro-centric childrens books. It was during this period that he first had the idea for Middle Passage: White Ships, Black Cargos, perhaps ironically, after he saw Malcolm Baileys Hold: Separate but Equal at the Whitney Annual in 1970. Feelings opinions about the young Baileys paintings differed from those of the critics who lauded him, and he furthermore disagreed with Baileys choice of spare and vacant minimalism to portray such a seminal African American icon. At the core, Feelings believed that Baileys work did not possess the depth of compassion needed to treat the subject of the Middle Passage, and he also disapproved of Baileys use of the slave ship icon to interpret issues of race relations and integration. Feelings began making the illustrations for his book in 1974, with the idea that they might serve as a memorial to the Middle Passage, something that, in his opinion, Baileys project failed to do. It is probably worth reiterating how much Feelings illustrations for Middle Passage: White Ships, Black Cargos occupy a place in the black American imagination. These illustrations were used on the cover of Charles Johnsons popular 1990 novel, Middle Passage, and as storyboard illustrations for Stephen Spielbergs 1997 film, Amistad. From 1998 until his death in 2005, Feelings traveled around the country giving slide-illustrated lectures about the genealogy of his book project and its memorial implications. The stained glass window, dedicated as the Maafa 2000 East Communion Window at the New Mount Pilgrim Missionary Baptist Church, is part of a larger discussion about paying tribute to the legacy of the Middle Passage. As the Rev. Hatch has commented, Its more than just church art, its part of contemporary discourse political and moral on how to repair African People (Walters, 2000: 24). Maafa is a Swahili word meaning great struggle and the New Mount Pilgrim community hopes to imbue this word with the similar type of significance as the Jews use of the word Holocaust. But the Maafa Remembrance 2000 East Communion Window is also part of a larger contemporary wave of iconoclasm, where

24

CHERYL FINLEY

predominantly black congregations around the country are replacing white figures with black figures in biblical art and stained glass. As Rev. Gregory Thomas, an adjunct faculty at the Harvard Divinity School has said, Its very important for people of color, but also others, to see that there are other icons and that they see themselves within those images. These are just pictures, but they have powerful meaningsThats why the Middle Passage picture is so important and we need to tell our children what this means (Fountain, 2001: C1). Another stained glass window at New Mount Pilgrim, Lift Holy Hands, replaces white figures with all black figures, including a Christ figure that wears an Afro. Surrounding the central image of the arisen black Christ figure, smaller circular stained glass windows spell out the word remembrance. At the very bottom, three circular windows depict an image of Africa, the communion ritual with wine and bread, and the dedication panel with the words Maafa 2000. The stained glass window then is clearly meant as a memorial. As the Rev. Hatch announced in his dedication speech, Maafa Remembrance 2000 not only acknowledges their humanity, but the memorial acknowledges their loss to humanity, and declares that we can neither be whole, or healed, or reconciled without their remembrance as part of our consciousness (Hatch, 2000). As a memorial, the Maafa Remembrance 2000 window has been responsible for attracting new parishioners and a large number of tourists. In fact, according to the Rev. Hatch, the widespread appeal of the stained glass window is not only welcome, but also part of the overall pedagogical goal in creating the window. After all, the Maafa Remembrance 2000 window is part of a larger project that involves educating people about the history of slavery and the Middle Passage and in the words of the Rev. Hatch, a contribution to the twenty-first century work of reconciliation (Hatch, 2000). Works cited BARAKA, Amiri. [LeRoi JONES] 1961. Preface to a Twenty Volume Suicide Note. New York: Totem Press. ______. 1963. Blues People: Negro Music in White America. New York: William Morrow and Co. ______. 1964. Dutchman and the Slave. New York: William Morrow and Company. ______. 1965. The System of Dantes Hell. New York: Grove Press.

1969

25

______. 1966. Home: Social Essays (New York: William Morrow and Company). 1998. Rpt. Home: Social Essays. Hopewell, NJ: Ecco Press. ______. 1968. Black Music. New York: William Morrow and Company. ______. 1969a. Slave Ship: A One Act Play. Newark: Jihad Productions. ______. 1969b. Four Black Revolutionary Plays. Indianapolis: The Bobbs-Merrill Company. ______. 1969c. Raise, Race, Rays, Raze: Essays Since 1965. New York: Random House. ______. Black Magic: Collected Poetry, 1961-1967. Indianapolis: The Bobbs-Merrill Company. ______. 1970. In Our Terribleness. Indianapolis: The Bobbs-Merrill Company. ______. 1979. Its Nation Time. Chicago: Third World Press. BARNES, Clive. 1969. The Theater: New LeRoi Jones Play. The New York Times, Saturday, November 22, 46. BROWN, Lloyd W. 1980. Amiri Baraka. Boston: Twayne Publishers. DU BOIS, W. E. B. 1973 [1896]. The Suppression of the African Slave Trade to the United States of America, 1638-1870. Milwood, New York: Kraus-Thomson Organization Limited. FAX, Elton C. 1973. Seventeen Black Artists. New York: Dodd, Mead and Company. FEELINGS, Tom. 1995. The Middle Passage: White Ships, Black Cargo. New York: Dial Books for Young Readers. Fabre, Genevieve. 1983. Drumbeats, Masks and Metaphors: Contemporary Afro-American Theatre. Cambridge, Harvard University Press. FINE, Elsa Honig. 1973. The Afro-American Artist: A Search For Identity. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, Inc. FINLEY, Cheryl. 1999. Committed to Memory: The Slave Ship Icon in the Black Atlantic Imagination. Chicago Art Journal 9, Spring, 221. ______. 2001. The Door of No Return. Common Place Vol. 1 . No. 4: http:/www.common-place.org/vol-01/no-4/finley. FOUNTAIN, John. 2001. Churchs Window on the Past, and the Future. The New York Times, February 9. GLUECK, Grace. 1969. Minority Artists find a welcome New Showcase. The New York Times, December 23, 21. HARRIS, William J. Ed. 1991. Amiri Baraka, The LeRoi Jones/Amiri Baraka Reader. New York: Thunders Mouth Press. HATCH, Rev. Marshall E. 2000. Maafa Remembrance 2000 Dedication Speech, www.newmountpilgrim.org.

26

CHERYL FINLEY

HUGHES , Langston & Milton MELTZER. 1956. A Pictorial History of the Negro in America. New York: Crown Publishers, Inc. ______. 1967. Black Magic: A Pictorial History of the Negro in American Entertainment, New York: Crown Publishers, Inc. ISAAC, Dan. 1971. The Death of the Proscenium Stage. The Antioch Review, Summer. JONES, KELLIE. 2006. ENERGY EXPERIMENTATION, BLACK ARTISTS AND ABSTRACTION, 1964-1980. NEW YORK: STUDIO MUSEUM IN HARLEM. NGABOH-SMART, Francis. 1999. The Politics of Black Identity: Slave Ship and Woza Albert! Journal of African Cultural Studies, Vol. 12, No. 2., December, 181-182. SCHEVILL, JAMES. 1973. BREAKOUT! IN SEARCH OF NEW THEATRICAL ENVIRONMENTS. CHICAGO: SWALLOW PRESS, INC. SCHMIDT CAMPBELL, Mary. 1973 [1896]. Tradition and Conflict: Images of a Turbulent Decade, 1963-1973. New York: Studio Museum in New York. Sollors, Werner. 1978. Amiri Baraka/LeRoi Jones: The Quest for a Populist Modernism. New York: Columbia University Press. WALTERS, Sabrina. 2000. Glass Recalls Slaverys Horror. Chicago Sun Times, December, 17: 24.

1969

27

Fig. 1. Plan of an African Ships lower deck with Negroes in the Proportion of only one to a Ton, 1789

28

CHERYL FINLEY

Fig. 2 Production still from Barakas Slave Ship, directed by G. Moses, 1969

1969

29

Fig 3. Description of a Slave Ship, 1789

30

CHERYL FINLEY

Fig 4. Malcolm Bailey with a mural size painting of his Separate but Equal series, 1969

1969

31

Fig 5. Malcolm Bailey, Hold: Separate but Equal, 1969

32

CHERYL FINLEY

Fig 6. Maafa 2000 Communion East Window, New Mount Pilgrim Missionary Baptist Church, Chicago

i

On March 25, 1807, the Abolition of the Slave Trade Act went into effect in Great Britain and her colonies. On March 2, 1807, the United States Congress approved a bill to abolish the slave trade, which was enacted on January 1, 1808. While these two legislative acts curtailed the slave trade significantly, the illegal slave trade continued nearly until the end of the nineteenth century, despite the efforts of British and American naval blockades. Chattel slavery as an institution in the British colonies was not abolished until 1833, with the Slavery Abolition Act, which freed all slaves in the British Empire in 1834, and in the United States, until 1865, with the passing of the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution. See Du Bois (1973 [1896]). ii On April 21, 1968, 100 black students took over Willard Straight Hall at Cornell University, demanding Africana Studies curricula and other resources for black students. This led to the first Africana Studies Department, the Africana Studies and Research Center, at an Ivy League research institution. The same year, at University of California, Berkeley, students rallied to demand courses and funding for Ethnic Studies. In 1969, Arno Press began reprinting classic literary and historical texts by black authors. Similarly, academic journals dedicated to black studies were

1969

33

begun and popular periodicals, such as Ebony and Jet, saw their subscriptions rise astronomically.

You might also like

- Gayle, Addison-The Black Aesthetic.-Doubleday (1971)Document461 pagesGayle, Addison-The Black Aesthetic.-Doubleday (1971)lucicruz100% (7)

- Black Fire An Anthology of Afro-American WritingDocument692 pagesBlack Fire An Anthology of Afro-American WritingStacy Hardy100% (2)

- EnigmasofhistoryDocument175 pagesEnigmasofhistorypstrlNo ratings yet

- Dutchman 1964 by Leroi Jones Amiri Baraka CompressDocument20 pagesDutchman 1964 by Leroi Jones Amiri Baraka CompressEmiliaNo ratings yet

- (Angelyn Mitchell (Ed.), Within The Circle PDFDocument38 pages(Angelyn Mitchell (Ed.), Within The Circle PDFszendyp100% (1)

- Flyworldshares New PlanDocument17 pagesFlyworldshares New PlanKrishna RainaNo ratings yet

- NN-sCA Graham Berry V OSA #BS116339 40 2008-09-19 1stamendmentDocument195 pagesNN-sCA Graham Berry V OSA #BS116339 40 2008-09-19 1stamendmentsnippyxNo ratings yet

- 6 Hats TwoDocument29 pages6 Hats TwoDeepthi .BhogojuNo ratings yet

- The State of Washington Constitutional FraudDocument2 pagesThe State of Washington Constitutional FraudDaniel Rothstein100% (1)

- Technocracy: It's All About Control Over All People, All Resources, and All Wealth (2017)Document2 pagesTechnocracy: It's All About Control Over All People, All Resources, and All Wealth (2017)Regular BookshelfNo ratings yet

- TRIMBERGER, Ellen. A Theory of Elite Revolutions PDFDocument17 pagesTRIMBERGER, Ellen. A Theory of Elite Revolutions PDFJonas BritoNo ratings yet

- What On Earth Happened Part 12Document41 pagesWhat On Earth Happened Part 12Nguyễn Hải YếnNo ratings yet

- The Age of MetternichDocument9 pagesThe Age of Metternichkry_nellyNo ratings yet

- Tymoshenko VavilovDocument58 pagesTymoshenko VavilovPolly SighNo ratings yet

- Spanish Holocaust Review RevisedDocument6 pagesSpanish Holocaust Review RevisedSathyaRajan Rajendren0% (1)

- Exposer AngalisDocument8 pagesExposer AngalisYassineNo ratings yet

- BlackAesthetics ReformattedDocument6 pagesBlackAesthetics ReformattedBETIE SONNITA TIQUAFONNo ratings yet

- Graphic Art From The Merrill C. Berman Collection: Art For Activism Lecture: 05 & 06Document43 pagesGraphic Art From The Merrill C. Berman Collection: Art For Activism Lecture: 05 & 06Talha ImtiazNo ratings yet

- Unit 9 (Contemporary Fiction)Document22 pagesUnit 9 (Contemporary Fiction)Laura CarniceroNo ratings yet

- Black Museum ModernDocument17 pagesBlack Museum ModernRaúl Moarquech Ferrera-BalanquetNo ratings yet

- Representation of Race and Black ArtDocument20 pagesRepresentation of Race and Black Artapi-641648266No ratings yet

- BlackartsmovementDocument2 pagesBlackartsmovementapi-265213353No ratings yet

- Art and Ativism Since The 1930sDocument8 pagesArt and Ativism Since The 1930sGuy BlissettNo ratings yet

- Art in The 1960sDocument19 pagesArt in The 1960scara_fiore2No ratings yet

- TheHarlemRenaissance 1Document5 pagesTheHarlemRenaissance 1Leire ScabiassNo ratings yet

- Abstract ExpressionismDocument4 pagesAbstract ExpressionismYaroslava LevitskaNo ratings yet

- Breaking Ground: Art Modernisms 1920-1950, Collected Writings Vol. 1From EverandBreaking Ground: Art Modernisms 1920-1950, Collected Writings Vol. 1No ratings yet

- Making the Movement: How Activists Fought for Civil Rights with Buttons, Flyers, Pins, and PostersFrom EverandMaking the Movement: How Activists Fought for Civil Rights with Buttons, Flyers, Pins, and PostersNo ratings yet

- A New African American Identity - The Harlem Renaissance - National Museum of African American History and CultureDocument4 pagesA New African American Identity - The Harlem Renaissance - National Museum of African American History and CultureRenata GomesNo ratings yet

- The Black Cultural Front: Black Writers and Artists of the Depression GenerationFrom EverandThe Black Cultural Front: Black Writers and Artists of the Depression GenerationNo ratings yet

- Excerpt From Revolution As An Eternal Dream...Document17 pagesExcerpt From Revolution As An Eternal Dream...redmarypNo ratings yet

- Introduction: Dada, Surrealism, and ColonialismDocument8 pagesIntroduction: Dada, Surrealism, and ColonialismDorota MichalskaNo ratings yet

- Disciplinary Movements, The Civil Rights Movement, and Charles Keil's Urban BluesDocument26 pagesDisciplinary Movements, The Civil Rights Movement, and Charles Keil's Urban BlueskennyspunkaNo ratings yet

- EnglishDocument34 pagesEnglishJediann BungagNo ratings yet

- De-Marxization of The Intelligentsia (From 'How New York Stole The Idea-Of-Modern-Art' by Serge Guilbaut) by Clement GreenbergDocument17 pagesDe-Marxization of The Intelligentsia (From 'How New York Stole The Idea-Of-Modern-Art' by Serge Guilbaut) by Clement Greenbergnemo nulaNo ratings yet

- A Brief Guide To The Harlem RenaissanceDocument4 pagesA Brief Guide To The Harlem RenaissanceanjumdkNo ratings yet

- American Literature LecturesDocument5 pagesAmerican Literature LecturesHager KhaledNo ratings yet

- Revolutionary Art Is Tool LiberationDocument7 pagesRevolutionary Art Is Tool LiberationDäv OhNo ratings yet

- Art in The 1960sDocument20 pagesArt in The 1960scara_fiore2100% (2)

- Frida Kahlo: A Contemporary Feminist ReadingDocument26 pagesFrida Kahlo: A Contemporary Feminist ReadingZsófia AlbrechtNo ratings yet

- 14 - Aesthetics: Modernismo and Vanguardismo, Which in Spite of Their Strong European InfluencesDocument8 pages14 - Aesthetics: Modernismo and Vanguardismo, Which in Spite of Their Strong European InfluencesPatrick DoveNo ratings yet

- What Was The Harlem RenaissanceDocument2 pagesWhat Was The Harlem RenaissanceSachely Walters DawkinsNo ratings yet

- The Harlem Renaissance - What A Complex and Conflicted Aura The Term Evokes!Document10 pagesThe Harlem Renaissance - What A Complex and Conflicted Aura The Term Evokes!bijader5No ratings yet

- Newark MuseumThe Great MigrationDocument15 pagesNewark MuseumThe Great MigrationLuc HotalingNo ratings yet

- Greeley Forum On Latin American WeissDocument12 pagesGreeley Forum On Latin American WeissJody TurnerNo ratings yet

- Harlem Renaissance PDFDocument7 pagesHarlem Renaissance PDFDon Baraka Daniel100% (1)

- Authors and MovementsDocument3 pagesAuthors and MovementsEva Mª AguilarNo ratings yet

- Literary PeriodDocument1 pageLiterary Periodh21kittyNo ratings yet

- A Brief Guide To The Black Arts MovementDocument1 pageA Brief Guide To The Black Arts MovementanjumdkNo ratings yet

- Black Africa and the US Art World in the Early 20th Century: Aesthetics, White SupremacyFrom EverandBlack Africa and the US Art World in the Early 20th Century: Aesthetics, White SupremacyNo ratings yet

- The Black Jacobins By: Graciela ChallouxDocument5 pagesThe Black Jacobins By: Graciela ChallouxNeteruTehutiSekhmetNo ratings yet

- Harlem RenaDocument3 pagesHarlem Renabanda.aashrithNo ratings yet

- Harlem Renaissance OverviewDocument3 pagesHarlem Renaissance Overview000766401No ratings yet

- Art and The Expression of FreedomDocument4 pagesArt and The Expression of FreedomJackie CrowellNo ratings yet

- айнураDocument28 pagesайнураblindladyNo ratings yet

- The Missing Future: Moma and Modern WomenDocument14 pagesThe Missing Future: Moma and Modern WomenAndrea GeyerNo ratings yet

- Africana Diaspora:: Destiny For AllDocument8 pagesAfricana Diaspora:: Destiny For AllAmina KalifaNo ratings yet

- Prerana Sarkar - Sem3 - CC5Document6 pagesPrerana Sarkar - Sem3 - CC5preranaNo ratings yet

- Unit 5:: The Harlem Renaissance and Modernism 1910-1940Document18 pagesUnit 5:: The Harlem Renaissance and Modernism 1910-1940ghitlerpatelNo ratings yet

- Posmodern American 60sDocument8 pagesPosmodern American 60sLuis Canovas MartinezNo ratings yet

- Harlem Renaissance BrochureDocument2 pagesHarlem Renaissance BrochureBenBCAPNo ratings yet

- CountercultureDocument9 pagesCountercultureMaider Serrano100% (1)

- The State of Rap - Time and Place in Hip Hop NationalismDocument33 pagesThe State of Rap - Time and Place in Hip Hop NationalismhakimNo ratings yet

- Adrienne Rich S Ghazals and The Persian PDFDocument261 pagesAdrienne Rich S Ghazals and The Persian PDFSwati SaniNo ratings yet

- Literary Criticism ReviewerDocument2 pagesLiterary Criticism ReviewerAldrin BallaNo ratings yet

- Kobena Mercer - Welcome To The Jungle - New Positions in Black Cultural Studies-Routledge (1994)Document356 pagesKobena Mercer - Welcome To The Jungle - New Positions in Black Cultural Studies-Routledge (1994)s1dbpinheiroNo ratings yet

- Privileged Spectatorship: Theatrical Interventions in White Supremacy by Dani Snyder-Young (Review)Document3 pagesPrivileged Spectatorship: Theatrical Interventions in White Supremacy by Dani Snyder-Young (Review)gabyNo ratings yet

- Neither Inside Nor Outside Mari Evans, The Black Aesthetic, and The Canon - Part2Document1 pageNeither Inside Nor Outside Mari Evans, The Black Aesthetic, and The Canon - Part2MansourJafariNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2 Literary Periods and MovementsDocument11 pagesChapter 2 Literary Periods and MovementsClaNo ratings yet

- Literary Movements: A. MetaphysicalDocument20 pagesLiterary Movements: A. MetaphysicalIan Dante ArcangelesNo ratings yet

- An Introduction To The Black Arts Movement - Poetry FoundationDocument11 pagesAn Introduction To The Black Arts Movement - Poetry FoundationLibier Velez SanchezNo ratings yet

- New York School MovementDocument4 pagesNew York School MovementRussell anne BautistaNo ratings yet

- Companion To African American NovelDocument339 pagesCompanion To African American NovelAdemário Hotep100% (2)

- Greg Tate. "The Black Male Show" "Amri Baraka"Document5 pagesGreg Tate. "The Black Male Show" "Amri Baraka"Jess and MariaNo ratings yet

- Identity, Race and Gender in Toni Morrison's The: Universidade Federal Do Rio Grande Do Sul Instituto de LetrasDocument64 pagesIdentity, Race and Gender in Toni Morrison's The: Universidade Federal Do Rio Grande Do Sul Instituto de LetrasCrazy KhanNo ratings yet

- Quashie Black AlivenessDocument31 pagesQuashie Black AlivenessKeeley Harper100% (1)

- The Jazz Peoples Movement Rahsaan Rola ND Kirks Struggle To Open The American Media To Black Classical Music.Document138 pagesThe Jazz Peoples Movement Rahsaan Rola ND Kirks Struggle To Open The American Media To Black Classical Music.dekknNo ratings yet

- THE REVOLUTION WILL NOT BE TRANSCRIBED: Black Politcal Praxis As Jazz Innovation in The 1960s by Benjamin BarsonDocument217 pagesTHE REVOLUTION WILL NOT BE TRANSCRIBED: Black Politcal Praxis As Jazz Innovation in The 1960s by Benjamin BarsonMarcel McVay100% (2)

- Is Performance Poetry Dead, GrabnerDocument5 pagesIs Performance Poetry Dead, GrabnershafieyanNo ratings yet

- Vdoc - Pub The Routledge Introduction To African American LiteratureDocument195 pagesVdoc - Pub The Routledge Introduction To African American LiteratureAlexandre RabeloNo ratings yet

- New York School Literary Movement and Black Arts Literary MovementDocument6 pagesNew York School Literary Movement and Black Arts Literary MovementKaren Masepequena100% (1)

- Soul of A Nation (Exhibtion Guid)Document16 pagesSoul of A Nation (Exhibtion Guid)Antonio SernaNo ratings yet

- Black AstheticsDocument15 pagesBlack AstheticsEdward KenehanNo ratings yet

- Henderson BluesAsBlackPoetryDocument10 pagesHenderson BluesAsBlackPoetryAnonymous FHCJucNo ratings yet

- JazzDocument27 pagesJazzRodrigo Del Rio Joglar100% (1)

- Invisibility and The Commodification of Blackness in Ralph Ellison's Invisible Man and Percival Everett's ErasureDocument17 pagesInvisibility and The Commodification of Blackness in Ralph Ellison's Invisible Man and Percival Everett's ErasureaanndmaiaNo ratings yet

- Kelley - Meditations On History and The Black Avant-GardeDocument16 pagesKelley - Meditations On History and The Black Avant-GardeMutabilityNo ratings yet

- African American Literary Tradition: A Study: Sudarsan SahooDocument58 pagesAfrican American Literary Tradition: A Study: Sudarsan SahooSpirit OrbsNo ratings yet