Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Task-Based Language Teaching in

Uploaded by

Akasha2002Original Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Task-Based Language Teaching in

Uploaded by

Akasha2002Copyright:

Available Formats

Task-Based Language Teaching in

Online Ab Initio Foreign Language

Classrooms

CHUN LAI

325 Hui Oi Chow

Science Building

Faculty of Education

University of Hong Kong

Pokfulam Road, Hong Kong

Email: laichun@hku.hk

YONG ZHAO

Education 170

1215 University of Oregon

Eugene, Oregon, 97403-1215

Email: yongzhao@uoregon.edu

JIAWEN WANG

Reno Hall 207

University of Detroit Mercy

4001 W. McNichols Road

Detroit, MI 48221-3038

Email: wangji7@udmercy.edu

Task-based language teaching (TBLT) has been attracting the attention of researchers for more

than 2 decades. Research on various aspects of TBLT has been accumulating, including the

evaluation studies on the implementation of TBLT in classrooms. The evaluation studies on

students and teachers reactions to TBLTin the online courses are starting to gain momentum,

and this study adds to this line of research by enhancing our understanding of the implemen-

tation of TBLT in an online ab initio course. This study investigated the implementation of

a TBLT syllabus in an ab initio online Chinese as foreign language course over a semester.

Surveys and interviews with the students and the instructors revealed that students reacted

positively to the online TBLT experience, and analyses of students performance at the end of

the semester suggested that this pedagogy produced good learning outcomes. This study also

identied some challenges and advantages of the online context for TBLT.

TASKBASED LANGUAGE TEACHING (TBLT)

has been attracting the attention of researchers

and language educators since Prabhu (1987) rst

proposed and experimented with task-based ap-

proaches in secondary school classrooms. The

essence of TBLT is that communicative tasks serve

as the basic units of the curriculum and are the

sole elements in the pedagogical cycle in which

primacy is given to meaning. TBLT presents a

way to realize communicative language teach-

ing at the syllabus design and methodology level

(Littlewood, 2004; Nunan, 2004; Richards, 2005).

Acknowledging the different approaches to task

denition, Samuda and Bygate (2008) dene a

pedagogical task as a holistic activity which en-

gages language use in order to achieve some

nonlinguistic outcomes while meeting a linguis-

The Modern Language Journal, 95, Supplementary Issue,

(2011)

DOI: 10.1111/j.1540-4781.2011.01271.x

0026-7902/11/81103 $1.50/0

C 2012 The Modern Language Journal

tic challenge, with the overall aim of promoting

language learning, through process or product

or both (p. 69). There has been a large volume

of research on the nature of different tasks and on

ways to sequence tasks (Bygate, Skehan & Swain,

2001; Robinson, 2005; Samuda, 2001; Skehan,

2001; Willis & Willis, 2007). Research has also

been carried out to understand the cognitive pro-

cessing involved in, and learners perceptions of,

task implementation (Ellis, 2005; Gulden, Julide,

&Yumru, 2007; Kumaravadivelu, 2007). The rapid

accumulation of literature has greatly enhanced

our understanding of pedagogical tasks and TBLT

syllabus design.

At the same time, researchers have stressed the

need for TBLT to be road-tested (Klapper, 2003)

and are urging for more classroom-based TBLT

research in different social contexts and differ-

ent classroom settings to shed light on tasks in ac-

tion and the various issues surrounding the imple-

mentation of TBLT in different contexts (Carless,

2007; Ortega, 2007; Seedhouse, 1999; Van den

Branden, 2006). Although classroom implemen-

tation of TBLT is gaining momentum and has

82 The Modern Language Journal 95 (2011)

been conducted in quite a variety of social and

instructional contexts (Leaver & Willis, 2004;

Littlewood, 2007; Van den Branden, Van Gorp &

Verhelst, 2006), TBLT in the online ab initio for-

eign language classroom context is still rarely

trodden territory (Duran & Ramaut, 2006). Un-

derstanding this particular instructional context

is of great interest as more and more K12 on-

line foreign language programs are being set up

to meet the increasing demands for foreign lan-

guage learning in this sector. This study intends

to ll the gap in the current TBLT literature by

presenting a semester-long experimentation with

TBLT in ab initio online Chinese as foreign lan-

guage (CFL) classrooms, examining students and

teachers reactions to it and discussing the issues

involved in its implementation in this particular

context.

RESEARCH BACKGROUND

TBLT in Classrooms

Over the past decade, TBLT has become the

topdown curriculum mandate at national or re-

gional level in quite a few places, such as Hong

Kong, Malaysia, Mainland China, and Flanders

in Belgium (Carless, 2008; Mustafa, 2008; Van

den Branden, 2006; Zhang, 2007). At the same

time, however, scholars and researchers are chal-

lenging the applicability of TBLT in K12 foreign

language contexts (Bruton, 2005; Klapper, 2003).

Thus, how well TBLT works in various K12 con-

texts, and what challenges practitioners might en-

counter when implementing TBLT in their class-

rooms have become pressing research issues.

Studies exploring the potential of TBLT in var-

ious classrooms have presented positive student

perceptions and learning outcomes. Ruso (2007)

conducted an action research study on the im-

plementation of TBLT in two rst-year university-

level English classes at an Eastern Mediterranean

University and reported positive perceptions and

increased participation from the students as well

as enhanced rapport between the students and

teachers. Lee (2005) experimented with TBLT

in a vocational high school in Taiwan over one

semester and came to a similar conclusion of

positive perceptions and enjoyment. Further, she

found that TBLT improved students self-esteem,

creativity, social skills, and personal relations.

McDonough and Chaikitmongkol (2007) piloted

a TBLT course with learning strategy training

modules in a Thai University and found that the

learners not only enjoyedthe course, but alsowere

becoming more independent learners. Demir

(2008) found that the implementation of 10 read-

ing tasks in two preparatory reading classes at a

university in Turkey resulted in learners develop-

ing the skills of learning on their own and becom-

ing autonomous in the reading process. Leaver

and Kaplan (2004) came to the same conclusion

when analyzing the TBLT courses at the Defense

Language Institute and the Foreign Service Insti-

tute in the United States: They found that TBLT

promoted learning how to learn and encouraged

risk taking among the students. They further ob-

served that the TBLT courses had a lower attri-

tion rate and higher performance scores than

any ever achieved in their language programs. A

quasi-experimental classroom study in Iran pro-

vided further evidence of the capacity of TBLT

to promote positive language learning outcomes

(Rahimpour, 2008). This comparative study of

two groups of intermediate-level English as a for-

eign language (EFL) learners over one semester

found that the group that followed a TBLT syl-

labus demonstrated greater uency and complex-

ity in their oral performance in story telling tasks

than the group that followed a structural syllabus.

However, in the meantime studies investigat-

ing the implementation of TBLT by classroom

teachers have raised a note of caution con-

cerning the classroom implementation of TBLT

in a few sociocultural contexts (Bruton, 2005;

Burrows, 2008; Littlewood, 2007). Burrows (2008)

pointed out that the sociocultural realities of the

Japanese context and the passive learning style of

the Japanese students as well as their over-reliance

on the teacher collectively weakened the imple-

mentation of TBLT in this particular context.

Carless (2002, 2003) found that teachers teach-

ing beliefs, the prociency levels of the students,

and the sociocultural realities of Hong Kong pri-

mary schools collectively contributed to teachers

transforming TBLT into task-supported teaching.

Similar factors were identied in the Korea and

Malaysia contexts (Li, 1998; Mustafa, 2008).

In particular, the following classroom factors

have been identied to challenge classroom-

based TBLT in K12 contexts: (a) crowded and

cramped classrooms creating discipline issues

everyone in the class starting to talk at the same

time inevitably brought uncontrollable and un-

welcome noises (Bruton, 2005; Carless, 2004,

2007; Li, 1998), and mixed prociencies in the

classroom made quicker students bored with hav-

ing nothing to do while slower students struggled

to complete the tasks (Mustafa, 2008); (b) stu-

dents of different prociency levels demonstrat-

ing unbalanced involvement and contributions

students with higher language prociency

Chun Lai, Yong Zhao, and Jiawen Wang 83

beneted more from doing tasks (Carless, 2002,

2003; Tseng, 2006), whereas students with lower

language prociency and with shy personalities

became frustrated at this taxing approach to

learning (Burrows, 2008; Karavas-Doukas, 1995;

Li, 1998); (c) in many cases, students avoiding

the use of the target language in fullling the

communicative tasks (Carless, 2008; Littlewood,

2007); and (d) students suffering from anxiety

over the freedom they were given in the TBLT

approach (Burrows, 2008; Lopes, 2004). Stu-

dents perceived slow learning progress (Leaver &

Kaplan, 2004; Lopes, 2004;) and held negative

perception towards too little grammar (Lopes,

2004; McDonough & Chaikitmongkol, 2008).

The above classroom studies have revealed the

potential benets of TBLTin classrooms and have

also shed light on the challenges language teach-

ers might encounter whenimplementing TBLTin

their face-to-face classrooms. Given the different

natures of face-to-face and online teaching, would

the potential of TBLT hold true in the online

teaching context, and what issues, similar or dif-

ferent, would emerge when implementing TBLT

in this instructional context?

TBLT in Online Classrooms

There has been a large volume of research on

learner performance of communicative tasks in

synchronous computer-mediated communication

environments that attest to the interaction-related

benets of performing tasks in a text-based on-

line chatting environment (see Ortega, 2009, for

a detailed review). There have also been longi-

tudinal studies on TBLT as extracurricular activi-

ties or projects for learners of different ages, and

these studies presented evidence that learners in-

corporated input fromtheir interlocutors (Smith,

2009), and that such incorporation had a lasting

impact on subsequent L2 use (Gonzalez-Lloret,

2008). Although these studies were conducted ei-

ther as lab sessions or extracurricular activities re-

lated to face-to-face classrooms, the positive nd-

ings did suggest the potential of implementing

TBLT in the online learning context. Researchers

have just started to investigate the implementa-

tion of TBLT in purely online courses, determin-

ing students reactions and unraveling how the

online context constrains or mediates its imple-

mentation (Hampel, 2006; Sole & Mardomingo,

2004).

Hampel and Hauck (2004) reported an ex-

ploratory study in an advanced-level online

German course. This course was run in an asyn-

chronous fashion with self-study materials and

discussion forums. For the sake of the study,

they added two whole-group (15 students) syn-

chronous TBLT tutorials in an audiographic con-

ferencing system, andtheir researchndings were

based on these two 75-minute tutorials. Although

the learners expressed overall satisfaction with

the tasks, the tutors reported that learners were

reluctant to speak and participate in the tasks

and that in some cases the tasks suffered from

dwindling participation. To achieve better learn-

ing outcomes, they suggested that tasks needed

to be designed in such a fashion that they can

be nished in a single tutorial and require less

preparation, and that more support in the learn-

ing process needs to be given to weaker students.

Hampel (2006) reported another study on an

intermediate-level online German course. In this

course, in addition to engaging in self-study of the

course materials and interacting with the instruc-

tor and peers asynchronously, the students were

given options to attend a series of voluntary task

tutorials throughout the semester. The tutors re-

ported the tasks to be quite successful, but they

also observed uctuating participation and reluc-

tant participation on the part of weaker students.

Furthermore, they commented on the difculty

of classroom management due to the lack of par-

alinguistic cues and the danger of tasks becoming

more tutor centered with small groups.

The above two studies examined learners with

an intermediate level of language prociency and

above, whichmakes one wonder whether the same

paradigm could be used on beginner learners,

ab initio learners in particular. Although Duran

and Ramaut (2006) and Rosell-Aguilar (2005) ex-

plored the issues related to the design of tasks for

online beginner learners, little data is available

on the actual implementation of TBLT in such

classrooms.

This study intends to ll the gap in the current

literature by examining online ab initio learners

reactions to TBLT and the issues that emerged

from the implementation of TBLT in this instruc-

tional context.

RESEARCH QUESTIONS

This study examined the implementation of

TBLT in the context of online ab initio foreign

language classrooms. Specically, two questions

were addressed:

1. What are online ab initio learners and

teachers reactions to TBLT?

2. What issues emerge from the implementa-

tion of TBLT in an online ab initio context?

84 The Modern Language Journal 95 (2011)

CONTEXT OF THE STUDY

Instructional Context

The current study was carried out in the on-

line ab initio Chinese courses offered at a pub-

lic virtual high school in the United States.

The online courses had both asynchronous

and synchronous components. The asynchronous

components included student self-study of the

e-textbook, additional online learning resources

(such as Chinese podcasts, Chinese character

learning software, and online Chinese dictionary)

and weekly language and culture assignments.

There were also asynchronous means of com-

munication, such as discussion forums and mes-

sage centers, which students could use to connect

with their classmates and their instructor. All the

learning materials and asynchronous communi-

cation tools were hosted in the course manage-

ment system, Blackboard (see Appendix A for a

snapshot of the course). The e-textbook used in

this course was Chengo Chinese (a sample unit:

http://www.elanguage.cn/episode02cut/), an in-

teractive courseware collaboratively developed by

the U.S. Department of Education and China

Ministry of Education. This was the only online

Chinese e-textbook for beginners available at the

time of the study. The e-textbook was organized

around the story of an American students sum-

mer camp experience in China and followed a se-

quence of modelpracticeapplicationgame for

each unit. The weekly language and culture as-

signments included one or two individual lan-

guage assignments (e.g., recording oral responses

to complete a dialogue; writing a short essay to

introduce their family), discussions on given cul-

tural topics, and self-reections on each weeks

learning progress and process. The instructor

gave written feedback on students language as-

signments in the grade center and monitored

their cultural discussions. Students could leave

messages for each other and for their instructor in

the message center and were encouraged to com-

ment on one anothers postings in the discussion

forums.

In addition to the learning and interaction

in the asynchronous course management system,

the students were required to attend one 1-hour

small group (35 students) synchronous session

with their instructor each week. The purpose of

the synchronous sessions was to give the online

students a chance to meet with their instruc-

tor and classmates weekly for online instruction.

At the beginning of the semester, students were

instructed to make a selection from the given

list of potential timeslots for synchronous ses-

sions, and the teacher assigned them into small

groups (35 members each) based on their se-

lection. Once the student had been assigned to

a group, he or she was to stay with the team

throughout the semester. The synchronous ses-

sions were conducted through a conferencing sys-

tem, Adobe Connect. This conferencing system

allowed text- and audio-chat,

1

and had a docu-

ment sharing function that enabled the instruc-

tors and students to share documents and make

annotations on the documents on the go (see

Appendix A for a snapshot of the conferencing

system).

Prior to the study, the online ab initio Chi-

nese course had been running in this virtual high

school for two years. The synchronous sessions

were usually run in the fashion of didactic teach-

ing and structured practice of linguistic items via

the typical InitiationResponseEvaluation (IRE)

classroom discourse pattern. In 2007, in the light

of the encouraging research evidence that TBLT

brings about better learning outcomes in foreign

language classrooms than traditional approaches

(Lever & Kaplan, 2004; Rahimpour, 2008), the

researchers introduced a TBLT syllabus to imple-

ment in this course during the synchronous ses-

sions. This TBLTsyllabus was implemented in half

of the online ab initio Chinese classes, while the

other half of the ab initio classes followed the syl-

labus used in the past.

The Task Syllabus

Since we did not have the capacity to designand

develop a TBLT e-textbook, we kept Chengo Chi-

nese as the e-textbook for the course, but designed

a TBLT syllabus to use during the synchronous

sessions. The tasks in the TBLT syllabus were con-

structed to expand the topic of each unit in the

e-textbook. For example, the rst unit of the e-

textbook was a conversation between a teacher

and her students on the rst day of a class, in

which they greeted each other and introduced

their names. Two tasks with associated pre- and

post- activities were designed to expand it through

engaging students in introducing academic infor-

mation as well as previous educational experience

(see Appendix B for the task design and the align-

ment of TBLT syllabus with the e-textbook). In

this course, students were usually given two weeks

to nish one unit in the e-textbook. Thus, two

TBLT sessions were designed to go with each unit,

and altogether, 12 1-hour TBLT sessions were de-

signed and implemented.

2

Chun Lai, Yong Zhao, and Jiawen Wang 85

The synchronous sessions followed a pre-task,

during-task and post-task cycle (Ellis, 2003; Willis,

1996). Following Williss suggestion for conduct-

ing TBLT for beginners, the cycle adopted a rel-

atively longer pre-task phase and a shorter task

phase with the planning and reporting stages

omitted. Considering the fact that the target pop-

ulation comprised absolute beginners of Chinese,

the pre-task phase focused on linguistic prepa-

ration and consisted of an array of activities

suggested by Ellis (2003, 2006)in some cases

students were guided and supported in perform-

ing a task similar to the one they would per-

form in the task phase (Prabhu, 1987); in some

cases, they were provided with a model of the

task with meaning-oriented activities around it

(Ellis, 2006); in other cases, there were a se-

ries of vocabulary-targeted activities that were de-

signed to prepare the learners to perform the

task (Willis, 1996). These pre-tasks were mainly

input-based tasks or activities aimed at familiar-

izing the students with the language needed for

the main task. The task phase consisted of one

or two output-based tasks that were designed to

engage learners in working together and using

resources available to achieve some sort of out-

come. During this phase, the instructors either

took a facilitative role or a participatory role

depending on the size of the group. The tasks

were sequenced in the light of Elliss (2003) task

complexity grading criteria (e.g., from written to

oral, from few elements/relationships to many

elements/relationships, from dialogic to mono-

logic). As for the post-task phase,

3

repeat perfor-

mance was usually designed to increase complex-

ity and uency (Ellis, 2003).

During the implementation, the instructors re-

viewed the tasks for the coming week together

with the researchers and worked collaboratively

to modify the tasks, when needed, in ways that

were more appropriate for their students (e.g.,

changing the destination of an imaginary trip to

make sure that every student knew the place).

METHOD

Participants

Thirty eight students from the ab initio classes

that adopted the TBLT syllabus during their syn-

chronous sessions volunteered to participate in

this study. The participants were all monolin-

gual Anglo-American high school students. They

ranged from 13 to 18 years old (the average age

was 16). There were 18 males and 20 females.

76% of the students had prior foreign language

learning experience, and 35% had studied two or

more foreign languages before. Exactly 88% of

the students had never taken any kind of online

courses, and 97% had never taken an online for-

eign language (FL) course. Students who missed

more than one third of the virtual meetings and

those who had any prior exposure to Chinese in

an instructional context were excluded.

The four instructors who were teaching the

TBLT classes ranged from 22 to 25 years old.

Three were female and one was male. Two of the

instructors had previous classroom foreign lan-

guage teaching experience. None of them had

taught online classes before, and none of them

had experimented with TBLT before. Aware that

working with novice teachers was quite risky and

might distort the way the TBLT syllabus was ac-

tually implemented in the classroom, measures

were taken to minimize this potential threat: the

teachers were given intensive workshops on TBLT

before the start of the semester and weekly debrief

sessions with the researchers to discuss the design

of the task cycle for the coming week and trou-

bleshoot the problems they encountered during

teaching.

We initiated the TBLT syllabus during the syn-

chronous sessions in the online ab initio Chinese

course believing that it could help enhance stu-

dents communicative abilities. To check whether

this expectation held, we included the perfor-

mance data of the control group of students from

the other half of the ab initio Chinese course

that did not implement the TBLT syllabus. This

control group consisted of 36 students of similar

proles

4

and the only difference between these

two groups was the syllabus adopted during the

synchronous sessions.

Data Collection

The study drew mainly on both learners and

teachers self-report data supplemented by learn-

ers performance data to shed light on students

and teachers reactions to TBLT as well as the

issues that emerged from the implementation of

TBLTinthis particular context. Six sources of data

were analyzed and triangulated to answer the two

research questions.

Background Survey. At the beginning of the

semester, a student background survey was ad-

ministered to the students in all the online ab

initio Chinese classes. This backgroundsurvey col-

lected basic demographic information as well as

students previous foreign language learning and

online learning experience.

Weekly Reection Blog Entries. During the

semester, the students were required to write

86 The Modern Language Journal 95 (2011)

self-reection blogs each week as part of their

weekly assignments to reect on their learning ex-

perience during the week. For each weeks reec-

tion blog, they were encouraged to talk about how

well they had done and what they had learned, the

challenges they had encountered, the strategies

they wanted to share with their classmates, and so

on.

Class Observations and Recorded Synchronous

Sessions. The researchers carried out weekly ob-

servations of one randomly selected session of

each TBLT teacher and took eld notes. All the

teachers in the online ab initio Chinese course

were asked to record their teaching sessions each

week using the recording function within the

video conferencing system. The recording cap-

tured every movement on the screen as well as

all the aural and written interaction between the

teacher and the students and among the stu-

dents. Thus, the recording provided minute-by-

minute replay of what was going on during the

synchronous sessions.

Course Evaluation. The course evaluation con-

sisted of three Likert scale questions (on a scale of

1 to 7) on their enjoyment of the course and per-

ceived learning and four open-ended questions

eliciting the aspects of the synchronous sessions

that they liked and disliked, their perceptions of

the synchronous sessions, and their intentions

concerning whether or not they would continue

to take the course in the coming semester. The

course evaluation items were posted as one of

their assignments for the last week of the semester

and the learners completed the course evaluation

in English.

Recording of Students Oral Production When

Performing a Descriptive Task during the Final

Exam. The nal exam was done in a one-on-one

fashion, where each student was given an exam

slot, and he/she logged into the conferencing

system alone to meet with the instructor. A mono-

logic picture description task

5

was used to elicit

students oral performance, andthe students were

asked to describe the picture orally. The same

examwas given to the students in all the online ab

initio Chinese classes, and the performance of all

the students during the nal exam was recorded

using the recording function in the conferencing

system.

Weekly Debrief and End-of-Semester Interview With

the Teachers. The TBLT teachers met with the re-

searchers every week to talk about their general

feelings about the weeks teaching and the chal-

lenges and/or the problems they had encoun-

tered, and to previewand comment onthe tasks to

be used in the coming week. The TBLT teachers

were also interviewed at the end of the semester

to obtain their reections on their overall TBLT

teaching experience during the semester.

The majority of the data described above came

from the students and teachers in the TBLT class-

rooms. The only two sources where the students

in the control classrooms were included were the

background survey and students performance in

the oral task in the nal exam. The control stu-

dents oral performance was included because it

enabled us to view the TBLT students learning

outcomes in the light of the students who had

not experienced TBLT in their synchronous ses-

sions. This comparative view helped us to evaluate

whether TBLT in the online ab initio FL class-

rooms had done a good job in enhancing stu-

dents communicative capacity, the intention that

drove the implementation of these pilot classes in

the rst place. We did not collect other data from

the control classrooms because the focus of this

study was not to test the relative effectiveness of

these two teaching methods, but rather to evalu-

ate and inform the implementation of TBLT in

an online ab initio FL instructional context.

Data Analysis

The data for the study was largely qualitative

in nature and consisted of students weekly self-

reection blogs, students course evaluation, re-

searchers classroom observation notes, the min-

utes of the weekly debrief meetings with the

teachers, and the teachers end-of-semester in-

terview data. An inductive approach was adopted

to discover the issues that emerged from the en-

tire corpus. Ad hoc transcribing and analyses of

the recorded synchronous sessions were also con-

ducted when they were called for to shed further

light into the issues identied. The recordings of

students performance in the oral descriptive task

were transcribed and coded on their uency, com-

plexity and accuracy. Statistical analysis was con-

ducted between the TBLT and control classes.

To answer the research question concerning

students and teachers reactions to TBLT, qualita-

tive analysis of students andteachers perceptions

and class performance throughout the semester

was conducted, supplemented with a quantitative

analysis of the uency, complexity, and accuracy

of students oral performance in the descriptive

task. Students course evaluations and teachers

interviews served as the primary data to obtain a

glimpse into their overall perceptions of the TBLT

experience. Students weekly reection entries

Chun Lai, Yong Zhao, and Jiawen Wang 87

throughout the semester were traced for changes

in their perceptions of, or the lack thereof, of

TBLT over time.

Students learning outcomes were analyzed to

shed light on the learning outcomes of the ex-

perience. The recordings of the oral descrip-

tive task performance of students in both TBLT

classrooms and control classrooms were tran-

scribed and double-checked by the researchers.

Then the transcribed oral data were coded on

three measures: uency, accuracy, and complex-

ity. Fluency was measured in terms of meaningful

words

6

/minute (Mochizuki & Ortega, 2008; Yuan

& Ellis, 2003). The transcripts were pruned by

deleting the instructors prompts along with the

rst language (L1) conversation with the instruc-

tor, and thus the time was the total time length of

the pruned performance. Accuracy was measured

in terms of error-free clauses (the percentage of

clauses that did not contain any error [Yuan &

Ellis, 2003, p. 13]). Syntactic complexity was mea-

sured by the mean length of T-units.

7

T-tests were

conducted on the three measures of oral produc-

tionbetweenstudents inthe TBLTclassrooms and

those in the control classrooms.

To answer the second research question con-

cerning the issues emerging from implementing

TBLT in an online ab initio context, TBLT stu-

dents reection blogs and the minutes of the

weekly debrief meetings with the instructors as

well as the end-of-semester interviews with the

teachers were analyzed to induce the general

themes of the challenges that students and teach-

ers had encountered as well as the potential that

the online context might have to facilitate TBLT.

Students and teachers data were triangulated

with the researchers observation notes to provide

a more comprehensive picture.

RESULTS

What Were Students and Teachers Reactions

to TBLT?

Both students and teachers overall percep-

tions of their TBLT experience and the students

oral language performance at the end of the

semester suggested that the majority of the stu-

dents and teachers in the online ab initio Chinese

classes reacted positively to TBLT. Analysis of the

data revealed the following issues: 1) students and

teachers expressed overall satisfaction with TBLT;

2) TBLT brought about progressive changes in

approaches to learning; 3) TBLT had differen-

tial effects on learners; 4) students lacked the ap-

propriate attitudes and strategies for TBLT; and

5) the features of the technological platformwere

crucial to the effects of TBLT.

Overall Satisfaction with TBLT

At the end of the semester, students rated their

enjoyment of the course positively (5.64 on a scale

of 7) and expressed satisfaction with the amount

of learning of the class (5.33 on a scale of 7).

As much as 83% of the students retained their

interest in learning Chinese and expressed wish

to continue learning Chinese, either in the next

semester or in the near future when schedules

allow. When checking student enrollment in the

following semester, we found that 56% of the stu-

dents actually came back to the next level online

Chinese class.

Some students enjoyed the novelty of the TBLT

learning experience: I like the atmosphere of the

experience, and I like the tasks a lot because it is

a little bit different from how I am used to learn-

ing. Others liked its student-centered nature: I

like the tasks in class because they are challeng-

ing and allow us to mess up and learn from our

mistakes, which is very helpful.

The majority of the students expressed great

satisfaction with the amount of learning they

achieved throughthe TBLTsynchronous sessions:

Its actually pretty impressive the amount of the

language that we did learn and that I have picked

up on; I have learned more from this one

semester than I think I have learned from all

my years of Spanish; This course as a whole

was probably the best course Ive taken and Ive

learned the most; and My views on the virtual

meetings were that they were fast paced but good.

Intense, but you came out feeling like you learned

a lot. They also felt that they could apply what

they had learned in the TBLT classrooms to real-

life scenarios: I felt like I learned things suf-

ciently enough to be able to use it in the real

world. More importantly, students appreciated

the fact that they were learning via doing and

speaking: I like the fact that we get to practice

speaking and learn by speaking with others in the

class; I learned a lot of grammar and language

from the hands on speaking and learning; and

In this class, I enjoyed all of the group activi-

ties, that required everyone to work and converse

together to complete the given assignment. Of

course, during the process, we would be learning

and applying new diction and syntax.

This perceived learning corresponded with

their oral performance in the nal exam (see

Appendix C for samples of their language pro-

duction). At the end of the semester (12 1-hour

88 The Modern Language Journal 95 (2011)

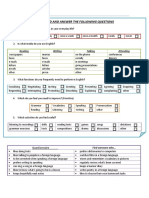

TABLE 1

Oral Language Production of Task-Based Language Teaching (TBLT) Classrooms vs. Control Classrooms

Condition Mean SD T Sig. Cohens D

Fluency TBLT 15.93 6.93 2.46 0.006

0.70

Control 11.93 4.33

Syntactic Complexity TBLT 5.86 1.62 1.98 0.748 0.07

Control 5.76 1.11

Accuracy TBLT 0.41 0.33 2.09 0.67 0.09

Control 0.38 0.28

TBLT sessions in total), the students in the

TBLT classrooms produced an average of 15.93

meaningful words per minute and 5.86 words per

T-units, with 41% of the clauses they produced

error-free. To make sense of these data, we

compared their performance with the perfor-

mance of students in the control classrooms.

We found that students in the TBLT classrooms

demonstrated signicantly higher uency in

language production than their counterparts in

the control classrooms

8

(T = 2.46, p = 0.006

, d

= 0.70), as was found in other studies of TBLT

(Liu, 2008; Rahimpour, 2008), and there was no

signicant difference in the syntactic complexity

and accuracy of the language production between

the two groups. Table 1

The data from interviews with the teachers re-

vealed that the teachers not only perceived TBLT

positively, but also believed that TBLT helped fos-

ter good learning habits and autonomy among

the students. One instructor commented:

Once they become familiar with this teaching pat-

tern, they know that they need to pay attention to

the language input and try to pick out the language

they dont know, but they need to know to complete

the task. Then they have a desire for the new lan-

guage. They become active learners to explore lan-

guage meaning and forms.

Their observations about the TBLTs potential to

foster autonomy was in line with Demirs (2008)

study, which found that TBLT experience helped

EFL learners become autonomous in the reading

process.

Progressions of Perception

The analysis of students weekly self-reection

blog entries across the 12 weeks revealed that

some students went through a shift in mindset. In

the following example, the student, as reected in

his self-reection entries over time, demonstrated

a shift from being totally reliant on the instruc-

tor for explicit instructions, to taking more and

more initiatives andresponsibilities inlearning on

his own:

In week 9, the student expressed an explicit

request for grammar instruction when he realized

that he had trouble constructing sentences: I am

not having any trouble pronouncing words; how-

ever, Im not very good at constructing sentences.

Id like it if we got some specic information on

how to make sentences and the specics of

sentence structure, i.e., some grammar.

In week 11, he started to demonstrate a shift in

his thinking, urging himself to take more respon-

sibility in actively guring out the grammatical

rules through self-discovery:

This week I learned numbers and addition in Chi-

nese. I also learned how to describe someone in a

picture to pick them out of a group. We also went

into more depth traveling and expenses. I can also

number things off like 5 computers (wu ge dian-

nao). I am having trouble with when to add and what

unit words like ge. I will try looking at more examples

and ndings patterns to use the right unit word.

His self-reection entry in week 15 showed that

he had come to internalizing the concept of inde-

pendent learning: This week, I added some new

words to my vocabulary such as squirrel and mush-

room. I also learned how to say something has a

certain amount of something. Lastly, I learned

how to say there isnt something in a room.

I still have trouble deducing sentence structure,

but I think Im improving. Chinese is really cool.

Encouraging as this potential was, such a pro-

gressive change of perceptions did not stand out

as a general theme in students self-reection en-

tries over time. It could be that some of them

went through similar changes, but just did not

make a note of it during their reection blogs. It

could also be that TBLT had differentiated effects

on students, and could only induce such changes

among only a few students.

Differential Effects of TBLT

An in-depth look at TBLT students perfor-

mance in the nal exam oral task revealed that

there was a great variation in their uency in

language production (see Figure 1).

Chun Lai, Yong Zhao, and Jiawen Wang 89

FIGURE 1

Variation in Students Oral Performance

M

e

a

n

i

n

g

f

u

l

W

o

r

d

p

e

r

M

i

n

u

t

e

Condition

Control Classes TBLT Classes

From the boxplots we can see that the students

in the TBLT classes seemed to be more divergent

in the uency of oral production than the stu-

dents in the control classes. There were several

extreme cases, even two outlier cases, in the TBLT

group: Several demonstrated extremely high u-

ency, while two demonstrated extremely low u-

ency. In the eld notes of classroom observations,

the researchers also noted the increasing differ-

ence in students performance when working to-

gether on tasks.

To get a better idea of the differentiated im-

pact that TBLT had on ab initio students, we

traced the self-reection blogs of two extreme

cases (case 56, who demonstrated extremely high

uency and case 60, who demonstrated extremely

low uency). Both case 56 and 60 were taught by

the same teacher and had similar prior foreign

language learning experience (Case 56 had stud-

ied French intensively and touched upon Spanish

and Hebrew; Case 60 had studied French for 3

years). Both categorized themselves as successful

learners (Case 60: I was fairly successful. I got an

A all three years), but one important difference

stood out in their background dataautonomous

learning skills. Case 56 sounded like a very au-

tonomous learner: Upon returning home af-

ter the exchange program ended, I taught my-

self the curriculum of French 3 and tried my

best to expand and enrich my vocabulary. When

asked about the successful foreignlanguage learn-

ing strategies he had used in the past, he listed

Music, news, radioexpose yourself to for-

eign culture . . . Furthermore, just seeking out lan-

guage mini-lessons online has worked for me

toothat is how I taught myself various verb

tenses during my freshman year. I want to point,

though, that when trying to internalize vocab-

ulary, write it down clearly and repeat it out

loud for multiple days; it can be so easy to for-

get vocabulary if not careful! In contrast, case

60 sounded less like an autonomous learner

and did not seem to have a good grasp of the

learning strategies Case 56 was talking about.

Although he categorized himself as a success-

ful learner based on the fact that he had ob-

tained A for three years, he acknowledged but

I am not particularly comfortable speaking it.

When asked about successful learning strate-

gies, he simply jotted down taking notes, learn-

ing about the culture, and listening to people

speak it.

This difference gave these two students quite

different learning experiences during the TBLT.

Case 56 demonstrated great initiative and useful

strategies to help himself stay abreast of learn-

ing. In week 5, he commented: Yes, it is going

to take me a little while to retain the words by

heart, but I think I have the initiative to do so. I

have fun searching for new words in the online

dictionary and attempting to use them correctly

in sentences. In week 10, he encouraged himself

to organize notes for learning: I wish I had more

time, because I would denitely arrange all of my

90 The Modern Language Journal 95 (2011)

notes in a more organized manner, so I can retain

the vocabulary more efciently. Perhaps I will do

that! In week 16, he summarized his learning ex-

perience and once again highlighted a successful

strategy he used:

I think that I have a good grasp of the material thus

farbut I could always improve with the vocabulary!

I do have sheets with vocabulary terms and examples

of sentence structures for each week of class, so that

makes it a bit easier to review everything that Ive

learned.

His reection entries over time suggested an opti-

mistic personwho continuously motivatedhimself

and took the initiative to search for learning re-

sources and opportunities and made active use of

strategies to help himself learn. However, when

looking at case 60, we saw a different trajectory.

In his week 6 reection, he expressed excitement

over the synchronous session, but sounded more

like a passive student: It is cool, but kind of hard. I

feel more comfortable with the words now. When

you are forced to say them, you kind of have to

learn them, but it was weird at rst. By week 9,

he seemed to have lost ground a little bit: I think

my pronunciation is okay, but the sentence struc-

tures confused me, especially when I couldnt nd

what the words meant. In the following weeks, he

continued to complain about the difculty of the

vocabulary, but did not think of any particular

strategies to use: I just need to keep studying.

By week 14, he had started to question his learn-

ing progress: I dont know that I am completely

comfortable with communication though, and in

week 16 he admitted: My biggest frustration was

just that I retained about ten percent of what I

should have.

Thus, it seems that TBLT might have a Matthew

Effect on online ab initio learners. For those who

had great initiative and knew how to motivate

themselves and how to learn strategically to start

with, TBLT seemed to give them opportunities to

achieve much. However, those who did not have

such resources at their disposal gradually lagged

behind and lost ground.

Students Lack Appropriate Strategies and Skills

for TBLT

Analysis of the minutes of the weekly debrief

sessions with the teachers identied several oft-

cited problems that teachers encountered. These

problems included students becoming easily frus-

trated over the extensive use of the target lan-

guage; students expecting the language needed

for the pedagogical tasks to be pre-taught; some

students not being active participants during the

group work, and being afraid of making mistakes;

some students not actively engaging in guessing

and deducing and always wait(ing) teachers to

tell them everything they need to learn; and stu-

dents expecting the instructor-led IRE type of talk

rather than they themselves playing the central

role: I ask a question, they answer. I stop, they

stop. Dont feel the students are independent.

Feel teachers are dominating the ow, and they

dont talk to each other if you leave them doing

the work. These comments showed that students

lacked some crucial strategies and attitudes with

respect to TBLT.

Analysis of students weekly reections also re-

vealed similar phenomena. They expressed a pref-

erence for explicit instruction: I dont like it

when the instructor talks only in Chinese and

you dont understand her and she wont trans-

late it for you; and If I had absolute freedom

in the virtual meeting, I would probably want to

spend more time breaking down sentences and

sentence structures. Some students lacked the

skills and attitudes needed for effective collabo-

rative group interaction (Hampel, 2006; Hampel

& Hauck, 2004): I think that, when we do the

tasks, people are shy. So, when we are supposed to

have a conversation, it isnt as talkative as it should

be. The only reason for this is that people dont

know each other and they arent entirely con-

dent in their answers. But once we get passed the

initial barrier, it is very fun; and I think that one

way for the meetings to improve would be if ev-

eryone would participate and not be afraid to get

an answer wrong. During the debrief sessions,

the teachers also lamented that on the occasions

when tasks were dominated by one or two indi-

viduals in the group: there might be a leading

student in the virtual classroom when doing task.

The others may rely on that student.

In addition to being hesitant about participat-

ing, students did not possess the necessary com-

municative skills. During class observations, we

noted that for some information gap tasks, some

students simply chose to read out whatever infor-

mation they were given and failed to take the op-

portunity to engage in negotiated interaction.

Important Features of the Technological Platform

for TBLT

The conferencing system used for the syn-

chronous sessions, Adobe Connect, had a whole

suite of annotation tools that enabled the teachers

tomake annotations onthe go. These tools turned

out to be critical to TBLT in the online ab ini-

tio context, as reected in a students comment:

I really liked that there were learning tools such

Chun Lai, Yong Zhao, and Jiawen Wang 91

as the text boxes, pointers and free hand pencil

to use to aid in lessons so that we could gure

out what was being talked about. The highlight-

ing tools provided visual cues for comprehension

and the annotation tools assisted formmeaning

mapping: Sometimes I was not able to under-

stand what was being asked until it was typed out

on the screen.

The conferencing system also allowed the in-

structors toswitchthe students fromthe default at-

tendee role tothe presenter role sothat they could

use the presentationtools, uploading pictures and

PPTs and using the highlighting tools. This func-

tion facilitated the learner-centered TBLT learn-

ing experience: I liked the virtual meetings, and

how we could interact with them using pointers

and other tools. It made it easier to learn since

it wasnt just a lecture, but something we could

be more a part of as students. This function

made it easy to incorporate student-generated in-

structional materials, and, by enabling alternative

means of participation, enabled the instructors

to conduct emergent instruction that catered to

not only the active students but also the relatively

passive students. For instance, during an input-

based task, although students were encouraged

to ask for help whenever they encountered un-

known phrases while processing the language to

achieve the goal, the instructor found that most of

the students did not want to speak up and initiate

questions. She changed the strategy by giving the

students the presenter role and asking them to

highlight the unknown phrases using the annota-

tion tools. As a result of this strategic move, all the

students participated. This function also helped

with learning: being able to write/draw for some

of the activities helped with memorization.

What were the issues that emerged from the

implementation of TBLT?

Analyzing the qualitative data, we identied a

series of issues related to the implementation of

TBLT in this online ab initio context. Some of

these issues were challenges, and others reected

the potential the online context might have for

facilitating TBLT for ab initio learners.

Challenges in Implementing TBLT

The challenges we identied in implementing

TBLT in the online ab initio course included the

following: 1) the challenge in designing an online

TBLTsyllabus and implementing the task cycle; 2)

the challenge in carrying out collaborative tasks;

3) the challenge posed by the Internet time lag;

and 4) the challenge in exclusive use of the target

language.

Challenges in TBLT Syllabus Design and Task

Cycle Implementation. We foundthat balancing the

role of the textbook and the TBLT syllabus was

a delicate issue in the online context. Long and

Crookes (1985) proposed that a TBLT syllabus

should start with needs analysis. In such a TBLT

syllabus, the textbook serves as all but one source

for the TBLT syllabus. This is relatively easy to

realize in most face-to-face FL classrooms, where

the interaction in the classroomis the centerpiece

of student learning. However, when designing

the experimental TBLT syllabus, we realized that

the e-textbook had to dictate the design of the

TBLTsyllabus since a large portionof the time our

students spent on this course was independent

studying of the e-textbook.

9

A great challenge in

aligning the TBLTsyllabus withthe e-textbook was

helping students to see the connection between

the two. Although we tried to relate the tasks to

the e-textbook, students might not have perceived

this connection: Most of what we covered didnt

pertain to what we were learning in the online CD

at the time.

The low frequency and short duration of the

synchronous sessions in the online courses posed

challenges to the preduringpost TBLT peda-

gogical cycle. It was difcult to complete all the

phases of the cycle in one session, and doing

so brought about complaints like the following:

what I did not like was that we tried to cover too

muchfor the allotted time frame. The instructors

felt really pushed to get everything done within

the 1-hour timeframe and noted that some of

the classes seems [sic] to be in a rushing pace. As

a result, in several sessions the post-task phase of

the cycle was left untouched. However, we could

not space out the cycle across two synchronous

sessions either since the next time the students

were to meet again was one week later, and the

effects of the TBLT cycle would thus be subject

to students memory and perceived connection

between sessions (Hampel & Hauck, 2004).

Challenges in Implementing Collaborative Tasks.

We found the inexibility of classroom arrange-

ment made it hard to promote positive group

dynamics. The spatial arrangement of the class-

room and the relative positioning of students and

between students and the instructor affects the

perceived power structure and is critical to over-

all group dynamics (D ornyei & Malderez, 1997).

In a face-to-face classroom, this could be achieved

through moving the chairs around or moving the

students around. However, in the virtual class-

rooms, all the participants names were listed

on the attendee list with the instructor marked

92 The Modern Language Journal 95 (2011)

prominently at the top with a differently colored

identity icon. This display of the meeting partici-

pants and the prominent position of the instruc-

tor made it hard for the instructor to fade out as

he or she could relatively easily do during group

activities in a face-to-face classroom.

Another logistic issue was related to student

grouping. Since the virtual sessions were con-

ducted with small groups of 35 and students

came to the virtual sessions at their scheduled

time, if one or two members did not show up,

the planned collaborative work would have to be

changed into individual work or become difcult

to proceed (Hampel, 2006).

Other than these logistic issues, the biggest ob-

stacle was the difculty in building a harmonious

relationship between the instructor and the stu-

dents and fostering rapport among the students,

which is much needed for active participation and

good group dynamics during task performance.

The instructors found that in the cases where the

synchronous sessions consisted of students from

the same school, the task performances were usu-

ally much more lively and engaging, with students

joking with each other and helping each other

along the way. Unfortunately, unlike in a face-

to-face classroom teaching context, the majority

of the synchronous sessions in the online learn-

ing context consisted of students from different

geographic locations, and students had no prior

knowledge of each other to start with. The lack

of physical contact and the limited interaction

among students made them virtually strangers to

each other even weeks into the class. As one stu-

dent pointedout, The give andtake betweenpeo-

ple in the class is slightly awkward, but I think that

is an inherent aw to an online class of strangers.

This constraint challenges the fostering of active

peer collaborative work in online TBLT.

Challenges Posed by the Delay of Sound Transmis-

sion on the Internet. TBLTrequires teachers to play

a facilitative role and to trust students to engage

in interaction while working on communicative

tasks. Thus, the teacher needs to be tolerant of

silence and give students time to sort out things

among themselves. However, the delay of sound

transmission on the Internet gave the teachers

a hard time in intervening at the right moment

(Hampel, 2006). Teachers tended to be less tol-

erant of silence because of the lack of physical

cues: I asked a question, and they kept silent. I

didnt know whether they couldnt comprehend

or were thinking of responses. I lost patience and

went ahead giving the English alternatives. The

instructors were also bothered a lot by the de-

lay of the sound transmission: Because the Inter-

net has delay, after I nished talking, 5 seconds

had already passed when it reached his side. In a

classroom, if he said nothing, I would know hes

thinking, but (in an online context) I dont know.

You would feel the silence is awkward and unbear-

able. The time wasted due to the lack of physical

cues and the delay of sound transmission made

the instructors concerned about the efciency of

virtual sessions, and they had to restrain them-

selves constantly from the urge to jump in and

instruct since its always much easier to tell the

students how to say something by concluding with

a formula or structure.

Challenges to Exclusive Use of Target Language.

The instructors found it particularly hard to main-

tain extensive use of the target language in this

instructional context. The instructors were under

pressure to use as much target language as possi-

ble, but extensive use of the target language usu-

ally made the students feel frustrated and was not

conducive to building up rapport with the stu-

dents: Sometimes I get confused and zone out

when you speak in Chinese; and I dont like it

when the instructors talk only in Chinese. The

difculty in providing visual cues in the online

context to facilitate comprehension further exac-

erbated the problemof using the target language.

At the same time the difculty in building up rap-

port in the online context also made it hard for

students to be patient, cooperative and tolerate of

ambiguity, which in turn discouraged the instruc-

tors from using the target language as well.

Potential Advantages of the Online Context

for TBLT

Despite all the challenges imposed on TBLT by

the online Ab Initio context, we found that this

learning context had some advantages that that

facilitated TBLT.

Some Technological Features Facilitate Emergent

Individualized Instruction. We found that the on-

line context provided more convenient venues for

student-centered teaching and emergent individ-

ualized instruction. As exemplied in a previous

section, one instructor found that the strategic

use of the attendees presentation privileges

while students were engaging with input-based

tasks, she grantedthe students presenter roles and

asked them to highlight the points that they were

struggling withenabled her to tap into students

learning processes and understand the problems

the students were encountering at any moment.

Chun Lai, Yong Zhao, and Jiawen Wang 93

Depending on the nature of the problem, she ei-

ther responded with a brief explanation for the

whole group or by means of a private text mes-

sage to the individual. The other teachers tried

this strategy in their classrooms and found it to

be a very effective strategy. This emergent individ-

ualized instruction may not be so easily and ef-

ciently realized in face-to-face classrooms, where

the solicitationof suchmoment-by-moment learn-

ing data often means chaos.

Online Anonymity Facilitates Group Work. The

anonymity of the online context was found to

facilitate the implementation of group work in

the TBLT classes. On the one hand, the natural

information gap induced by the anonymity lent

itself to the easy construction and implementa-

tion of some information gap tasks. For example,

because the online students did not know one

another and could not see one another, an infor-

mation gap task was naturally createdstudents

described their own personal appearances and

the group members drew portraits of them based

on the descriptionwhich would not be an infor-

mation gap task at all in face-to-face classrooms.

On the other hand, the anonymity also helped

to stimulate greater student participation during

task performance. One student commented on

how the anonymity online helped reduce anxiety

during oral production:

In any foreign language, there are always those dia-

logues you have to do with your partner in front of

the class. Sure we do dialogues with each other taking

turns etc. but we dont have the pressure like we would

in a classroom with 30 other pairs of eyes staring back

at you.

Such a liberating effect of anonymous online

interaction has been widely reported in the in

the computer-mediated communication (CMC)

literature (Beauvois & Eledge, 1996; Kitade, 2000;

Ortega, 2009).

Co-Availability of Text- and Audio- Chatting

Mediates Learning. The conference system used

in this study allowed both text chatting and au-

dio chatting. This feature made it easier for the

instructors to address individual learning needs

without breaking the ow of the communication,

as in the example we illustrated previously. There

were also a lot of cases where students sent private

text chat messages to their teachers to elicit indi-

vidualized help when they did not want to bother

their group-mates and did not want to look fool-

ish in front of their group-mates. It also provided

a more inviting venue for the shy students to

interact with their teacher and peer learners

(Kern, 1995).

Students reported that text-chatting helped to

lower the cognitive load of the tasks (Ortega,

2009) and facilitate both comprehension and pro-

duction (Ellis, 2003). In the self-reection blog,

one student noted: the aspect I had the hardest

time with in class today was understanding what

was being said orally. I can understand the ques-

tions when they are typed out, but when people

answered or asked verbally, I cant quite follow

them. The teachers also observed the same phe-

nomenon: its a good idea to ask them to work

together by text chatting. They can communicate

better by texting in the online classroom. How-

ever, at the same time, students who were slow

at typing found it annoying, as one student said,

what I say is usually behind in the conversation

by the time I nish typing it.

SUMMARY OF FINDINGS

In this study we found the online ab initio

Chinese students and teachers reacted positively

to the TBLT syllabus that was tried out in their

classrooms, as reected not just in their overall

perception of the experience, but also in the stu-

dents end-of-semester oral production. Some stu-

dents also demonstrated a change in mindset in

their approach to learning over the semester. At

the same time, we found that TBLT demonstrated

differentiated effects on the students, and the ma-

jority of the students lackedthe appropriate strate-

gies and skills needed for effective TBLT. In addi-

tion, the implementation of TBLT in the online

ab initio context encountered challenges in the

construction of the TBLT syllabus and problems

in implementing the full task cycle. The imple-

mentation of collaborative tasks also encountered

obstacles due to the inexibility of the virtual

classroom arrangement of the particular confer-

encing system and the difculty in building rap-

port among online students. The delay of sound

transmission and the deprivation of paralinguistic

aids in the online context also posed great dif-

culties in various aspects of TBLT. At the same

time, however, the online context was also found

to have great potential for the implementation

of TBLT, such as facilitating emergent individual-

ized instruction, lowering the cognitive load for

ab initio learners, and encouraging student par-

ticipation.

DISCUSSION

This study revealed a series of issues emerg-

ing from implementing TBLT in online ab

initio Chinese classrooms. Some issues identied

94 The Modern Language Journal 95 (2011)

were very much the same as those of TBLT in

face-to-face classrooms: (a) the need for strategy

training to familiarize students with the philoso-

phy and principles of TBLT and to help students

develop the appropriate strategies and skills that

facilitate TBLT (McDonough & Chaikitmongkol,

2007); (b) the difculty with the use of the tar-

get language (Carless, 2003; 2007); (c) the po-

tential of TBLT to change students approaches

to learning and facilitating autonomous language

learning (Demir, 2008; Leaver & Kaplan, 2004);

and (d) the unbalanced involvement of, and

contribution from, the students due to the lack

of appropriate attitudes and strategies for TBLT

(Carless, 2002, 2003; Tseng, 2006). Some other

ndings differ from the face-to-face TBLT class-

roomliterature due to the particular nature of the

online context. For example, Ruso (2007) found

that TBLT increased students rapport whereas

in this study, we found the lack of, and dif-

culty in building up, rapport in the online con-

text created a big obstacle to TBLT. Other nd-

ings in this study offer suggestions for face-to-face

classroom TBLT. For example, the face-to-face

classroom TBLT literature reports that shy stu-

dents and students with low language prociency

nd TBLT a taxing and stressful learning context

(Burrows, 2008; Karavas-Doukas, 1995; Li, 1998).

However, in this study, we found that the availabil-

ity of text-chatting in the online context helped

to mitigate stress and anxiety levels and lower the

cognitive load of the tasks for these types of stu-

dents. Furthermore, the nding that the confer-

encing system enabled teachers to tap into stu-

dents moment-by-moment learning process and

to engage in emergent individualized instruction

suggests that current face-to-face TBLTmight ben-

et fromcapitalizing onthis potential by blending

some online components into current syllabuses,

such as incorporating some text-chat tasks.

Although this study was based on a particular

instructional design in a special conferencing sys-

tem, and some of its ndings may not be gener-

alizable to other online FL teaching contexts, it

does provide some suggestions that could apply

to all online ab initio FL classrooms.

LEARNER AND TEACHER STRATEGY

TRAINING FOR ONLINE TBLT CLASSROOMS

In this study, we found an intricate relation-

ship between TBLT and learning autonomy. On

the one hand, TBLT helped a few students

to become more independent in learning. On

the other hand, the varying degree of learning

autonomy students demonstrated prior to the

TBLT class brought them differentiated learning

experiences. The seemingly contradictory nd-

ings collectively pointed towards the importance

of learner strategy training during TBLT: TBLT

needs learner strategy training to enhance its ef-

fect, and at the same time TBLT may reinforce

the effectiveness of strategy training by fostering

autonomous learning among the learners.

McDonough and Chaikitmongkol (2007) pro-

vided some great ideas on teacher and learner

strategy training. They recommended familiariz-

ing learners with the philosophical, pedagogical,

as well as assessment principles of TBLT prior to

the course. We would like to add that in the on-

line context, an extra step needs to be added to

this macro-level training: Helping students see the

connection between the TBLT syllabus and the

e-textbook or tutorials and understand how to or-

chestrate both for their online learning.

Furthermore, this study found that many stu-

dents lacked some basic strategies and skills that

are benecial to TBLT, such as building rapport

among each other and maintaining group dynam-

ics. Thus, a successful training program should

also include micro-level features whereby stu-

dents are guided in developing specic metacog-

nitive strategies (e.g., what linguistic features to

attend to during the text-based chatting), cogni-

tive strategies (e.g., howto negotiate meaning and

form in online chatting), social strategies (e.g.,

how to build rapport with each other and main-

tain group dynamics in the online context), and

affective strategies (e.g., how to keep themselves

motivated and actively engaged in the absence of

proximity with the instructor and peers).

In addition to training learners with relevant

strategies and skills, online FL teachers should

constantly think about how to create online com-

munities to foster rapport among students, and

what sort of warm-up activities or chit-chats can be

included at the beginning of each synchronous

session to initiate students into active participa-

tion and live interaction. It is equally crucial

to build up and foster connections among the

students with collaborative assignments, such as

peer interviews or group projects, that force stu-

dents to interact more with each other

10

and en-

hance students understanding of one another.

Online FL teachers should also familiarize them-

selves with the pedagogical affordances of vari-

ous features of the technological platform and or-

chestrate various technological means to support

TBLT. Moreover, online FL teachers should be

aware of the potential effect of the delay of sound

transmission on their intolerance of silence, and

think of strategies to overcome this tendency and

Chun Lai, Yong Zhao, and Jiawen Wang 95

at the same time think of ways to turn this delay

into active learning moments for the students.

IMPLREMENTATION OF THE TASK CYCLE

IN SYNCHRONOUS SESSIONS

In this study we encountered a dilemma in im-

plementing the full preduringpost task cycle for

ab initio learners due to the limited duration and

frequency of the synchronous sessions. One solu-

tion might be to arrange some, if not all, input-

based tasks for the pre-task phase as assignments

to be done independently or collaboratively prior

to the synchronous sessions and start with the syn-

chronous sessions with either an integrative pre-

task or a review task to lead into the during- and

post-task phase of the cycle. We have implemented

this change in our current online ab initio courses

and found this arrangement works very nicely in

addressing the issue.

ENHANCING THE COMPREHENSIBILITY OF

THE TARGET LANGUAGE IN ONLINE AB

INITIO CLASSROOMS

Online ab initio FL classrooms are challenged

by the contradiction between the lack of paralin-

guistic cues in the audio-based online classrooms

and the massive visual scaffolds ab initio students

need. To deal with this challenge, teachers need

to prepare abundant visual stimulus ahead of time

to facilitate the smooth ow of TBLT. Teachers

may prepare word galleries with rich visual infor-

mation and make them available for students to

manipulate during tasks. Such measures offer the

possibility of maximizing the use of the target lan-

guage without leading toincomprehensiononthe

part of students. It is equally important to build up

routines and use consistent language supported

with pictorial cues when giving task instructions

in order to promote greater understanding on

the students side.

SELECTION OF TECHNOLOGICAL

PLATFORM FOR ONLINE AB INITIO

FOREIGN LANGUAGE COURSES

The conferencing system we used for the syn-

chronous sessions has a whole suite of functions

that carry a variety of pedagogical potentials for

TBLT. These features include text-chat with both

public and private message functions, various an-

notation tools that allow drawing, highlighting

(among others), the function to turn students

into presenters, and a multiple document shar-

ing function that enables the concurrent display

of the task page and the word gallery. These fea-

tures were found to facilitate TBLT in the online

ab initio FL courses in this study. When selecting

the technological platform for the online ab ini-

tio TBLT FL courses, teachers need to consider

carefully the technological features that provide

various levels of visual and cognitive scaffolding

that enable emergent individualized instruction,

that encourage active involvement without height-

ening anxiety levels, and that make the tasks fun

and appropriately challenging for their ab initio

learners.

CONCLUSION

In this study we explored the implementa-

tion of TBLT for ab initio foreign language

learners in an online context and found that

it was well perceived among the students and

teachers and produced good learning outcome

as well. At the same time, we encountered

a number of issues when conducting TBLT

in the online ab initio CFL classes. Some

issues, like the lack of appropriate learning

attitudes and strategies and the challenge of

engaging students in active participation, are