Professional Documents

Culture Documents

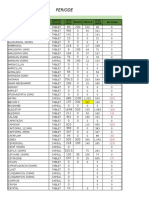

Top 20 Pharmas

Uploaded by

HimOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Top 20 Pharmas

Uploaded by

HimCopyright:

Available Formats

Top 20 Pharmas

based on 2010 revenues, in millions 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Pfizer Novartis Merck &Co. Sanofi GlaxoSmithKline AstraZeneca Johnson &Johnson Eli Lilly &Co. Abbott Laboratories Bristol-Myers Squibb Teva Takeda Pharma Bayer Schering Boehringer-Ingelheim Astellas Daiichi-Sankyo EISAI Otsuka Pharmaceutical Gilead Sciences Mylan $58,523 $44,420 $39,811 $37,403 $36,156 $32,515 $22,396 $21,685 $19,894 $19,484 $16,121 $14,829 $14,485 $12,883 $11,161 $10,794 $8,542 $8,440 $7,390 $5,404

Regulated to unregulated refers to the spectrum of control a govt institutes in the pharmaceutical industry, from requiring papers of R&D depts, reviewing results ofclinical drug trials, and controlling the environment in which a drug is manufactured through tough licensing laws. Some countries make you jump through hoops, others could care less, or they have laws in writing which are not diligently enforced. The changing dynamics of the global pharmaceutical industry especially that of the regulated markets like USA and Europe have presented a number of opportunities forIndian Pharmaceutical Industry to capitalize on. Japan, the world's third largest and one of the most regulated pharmaceutical marketsglobally, is emerging as the new attractive destination for Indian drug majors. The Latin American (Latam) pharmaceutical market is a semi-regulated market. Brazil is the largest pharmaceutical market in South America and ranks eleventh globally. It is an attractive semi-regulated market, offering immense opportunities for speciality pharmaceutical companies, Glenmark said. The Government of Lebanon continuously tries to control and limit medication costs. The market for medications, which accounts for 35-40 percent of health care expenditures, is largely unregulated Market Failure and the Pharmaceutical Industry: A Proposal for Reform By Sean Gabb www.seangabb.co.uk September 30, 2005

The award last month of 141m ($250m) against Merck for the alleged deficiencies of its painkilling drug Vioxx has brought the whole pharmaceutical industry into public discussion. We can, of course, deplore the vagaries of the American legal system. It is unlikely that the plaintiff in this particular case will ever see much of her compensation. The award will be contested in appeal after appeal. These will drag on for years to the ultimate enrichment only of the lawyers concerned. The case does, nevertheless, raise general issues of how the pharmaceutical industry conducts itself. There can be no doubt that the pharmaceutical industry as a whole has achieved and is achieving what would once have been regarded as miracles. It has created new products that cure or alleviate sickness and that have extended both the length and quality of life. This much has been achieved so far. There is every reason to believe that the future will bring still greater progress. Even so, the pharmaceutical companies have never been popular in the way that companies like Compaq and Apple Mackintosh have managed to become. They are distrusted where not actively disliked. The present case against Merck is just one instance of a growing prejudice. Since the 9th September 2004, the Health Select Committee of the House of Commons has been examining the influence in Britain of the pharmaceutical industry. The Committee is looking at how the industry affects government, regulators, healthcare professionals and consumers, and at the effects of this influence on public health. It has examined witnesses and considered written submissions by interested persons and organisations. The hearings began as a result of the obvious disquiet over the behaviour of the pharmaceutical companies. To be fair, there is some reason for disquiet. The pharmaceutical companies are limited companies, and their first duty is to maximise the return on their investments for dividing among their shareholders. As said, they have done and are doing often

marvellous things. But they have also been caught many times engaged in questionable or even immoral conduct. Let us consider some of this conduct, most though not all of it revealed to the Committee.

The Case against the Pharmaceutical Companies

Underhand Promotion

Marketing Ineffective or Dangerous Products

In 1998, GlaxoSmithKline published an internal memorandum, Towards the Second Billion a reference to sales of $1 billion already in which it discussed marketing strategies by which sales of Seroxat could be increased. This is a powerful antidepressant, and it was suggested that sales might be increased by persuading people to take it who were not seriously depressed.[1] Pharmaceutical companies run disease awareness campaigns, in which, according to Dr Iona Heath, speaking before the Commons Health Select Committee, they deliberately frighten patients about conditions that are not serious enough to require special medication, and thereby increase pressure on general practitioners to prescribe those medications. She calls this a policy of deliberate disease creep.[2] Pharmaceutical companies have been accused of setting up front groups to urge sale of their products. In April 2000, for example, Schering Healthcare and Biogen Ltd were investigated by the Commons Select Health Committee for funding apparently independent campaigning groups, which set up websites and bought advertising space in newspapers to recommend their products to the public.[3] Pharmaceutical companies seek to influence general practitioners to prescribe their new products by inviting them to conferences in expensive locations, where they are given lavish hospitality and are loaded with presents. According to Professor David Healy of the University of Wales, the pharmaceutical companies regularly arrange for endorsements of their products to be published in the medial press. He told the Commons Health Select Committee in October 2004 that as many as half the articles published in journals such as The British Medical Journal and The Lancetwere ghost written for the pharmaceutical companies, and that respected clinicians were then paid to have their names put at the top of the articles, even though they had not seen the raw data on which they were based. He gave the example of an article he had refused to father that later appeared bearing the name of Siegfried Kasper, from the Department of General Psychiatry at the University of Vienna.[4] Doctors are paid large fees for giving apparently spontaneous endorsements of pharmaceutical products to other doctors. Apparently, some senior medical consultants receive consultancy fees of more than 20,000 for a few hours work. Experts can also earn more than 4,000 an hour for extolling the virtues of new drugs to other doctors.[5] According to the Royal College of General Practitioners, giving evidence in August 2004 to the Commons Health Select Committee, normal variations in peoples health are now arbitrarily being classified as diseases and that companies are more interested in selling preventative drugs to the healthy than in healing the sick. It calls this practice disease mongering.[6] Large amounts of money are spent on marketing products which do not work. The medications presently used to treat Alzheimers disease have been said by the companies producing them to have impressive results. But it now emerges that they have little impact on halting the progression of the disease or allowing people a better quality of life.[7] Worse than this, two drugs, often prescribed for dementia, may not only be ineffective but one may even accelerate mental decline. Quetiapine (sold as Seroquel) and rivastigmine (Exelon) are prescribed to nearly half the patients with dementia in residential homes in Britain, often for long periods. Patients are given the drugs to control behavioural changes such as agitation, which are disturbing to them and make them more difficult to look after. But a trial in Newcastle has suggested that the drugs are ineffective and, in the case of quetiapine, accelerate the progress of the disease. The trial, funded by the Alzheimers Research Trust, involved 93 people with Alzheimers living in care homes in Newcastle. It was led by Clive Ballard, of the Institute of Psychiatry at Kings College London. The patients were treated with quetiapine, rivastigmine or a placebo pill. Neither of the groups given the active drugs showed any benefit in their agitation symptoms over six months. Those given quetiapine showed a much more rapid decline in mental capacities. A report published in The British Medical Journal says that it should not be used to treat such patients.[8] In February 2005, patients taking any Cox-2 inhibitors which include Celebrex, Bextra and Arcoxia, these being used to treat pain and inflammation in osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis, and in the management of acute pain were officially advised to stop their treatment immediately if they suffered from heart disease or stroke The European Medicines Agency said that patients on Cox-2 inhibitors, anti-inflammatory drugs used by more than a million Britons, should observe urgent safety restrictions after a comprehensive review. This action came after growing concerns about evidence suggesting a raised risk of heart attacks or strokes linked to the class of drugs. Doctors were instructed to exercise caution in prescribing to any patients who might be at increased risk of heart disease such as smokers, diabetics and sufferers of hypertension and high cholesterol.[9] Vioxx, another bestselling painkiller, was withdrawn by the pharmaceutical company Merck in September 2004 after a study of cancer patients showed a similar increased risk. Vioxx had been prescribed to 400,000 Britons at the time, many of whom were then given Celebrex and Arcoxia instead.[10] The present award of 141m may be followed by claims of ten or twenty times this amount by British litigants alone. Pharmaceutical companies pay general practitioners to test their new products on patients. Some of these tests are secret. In some cases, patients are given medications they do not need. At the same time, other patients are denied medications they need, so they can be used to measure the effectiveness of the tests. In 2002, for example, Dr Robert Adams tested Paroxetine, a new anti-depressant produced by GlaxoSmithKline, on a patient without her knowledge and consent. She suffered severe side effects. An investigation by the General Medical Council found that Dr Adams had received more than

Unethical Behaviour

Suppression of Unwelcome Information

100,000 during the previous five years from various companies, and that many of the tests had also been run without the consent of his patients. According to an investigation by The Observer newspaper, there are around 45,000 such trials every year, bringing general practitioners around 1,000 per patient even if only about one per cent of these trials are run without consent, and if the companies sponsoring them are not implicated in these trials.[11] Some pharmaceutical companies are seeking to end the practice of parallel imports, whereby products are imported into this country from other countries where the products are sold at lower prices. GlaxoSmithKline, for example, is accused of setting maximum order sizes on wholesalers in cheaper countries, the effect of which is to force up demand for the products in this country from the manufacturers.[12] Pharmaceutical companies only publish trial reports favourable to their products. GlaxoSmithKline, for example, is alleged to have withheld information that Seroxat increased the risk of suicide in children. Since the information was published, Seroxat has been banned from prescription to persons under the age of 18.[13] A pharmaceutical company was accused before the Commons Health Select Committee in November 2004 of having offered Peter Wilmshurst, consultant cardiologist at the Royal Shrewsbury Hospital two years salary to suppress results of a trial that showed its products were both deadly and ineffective. He refused the bribe and the drug was subsequently banned after his results were published.[14] He explained to the Committee: I know the pharmaceutical industry influences the research that is published. I suspect this is as common now as ever. I think it is very common. People are influenced by opinion leaders who are paid consultants to the company.

The War against Vitamins

For many years now, the pharmaceutical companies have been accused of working to limit access to vitamins and other dietary supplements. The main vehicle for this limitation is the Codex Alimentarius. This is an organisation set up in 1962 and affiliated to the United Nations. Its purpose is to harmonise regulations across the world on a range of issues related to food. For the past decade or so, it has been working in conjunction with the main pharmaceutical companies to destroy the growing market in dietary supplements. On the 4th July this year, it recommended laws in every country to require labelling that contains information on maximum consumption levels of vitamins and mineral food supplements, assisting countries to increase consumer information, which will help consumers use them in a safe and effective way.... The guidelines say that people should be encouraged to select a balanced diet to get the sufficient amount of vitamins and minerals. Only in cases where food does not provide sufficient vitamins and minerals should supplements be used. So long as the Codex was purely a creature of the United Nations, its recommendations were of little importance. They could be adopted or ignored as member states pleased, and most governments generally ignored them. Since the early 1990s, however, the Codex has been recognised by the World Trade Organisation. All member states are now obliged by treaty to incorporate the provisions of the Codex into their domestic law. Failure to do this may lead to international sanctions and even expulsion from the World Trade Organisation. The European Union has already imposed its own regulations. On the 1st August this year, the Food Supplements Directive, based on 1998 German regulations that emphasize maximum upper limits, came into force.[15] If ever carried fully into effect, this will take as many as 5,000 products off the European market. The Directive does not explicitly require bans on any products. It instead lays down rules on testing that will for reasons of cost prevent most supplements from remaining on the market. It also requires limitations on dosages that can be sold without a medical prescription. The meaning of this Directive is explained in a British Government news release: The Food Supplements Directive 2002/46/EC came into force in July 2002 and was implemented in England by the Food Supplements (England) Regulations 2003. Separate, equivalent legislation has been made in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. The directive and these regulations apply from 1 August 2005. One of the provisions of this directive is for lists of nutrients and their sources that can be included in food supplements. The first list covers the vitamins and minerals that may be used in food supplements (such as vitamin C, calcium, iron). It excludes six minerals (tin, silicon, nickel, boron, cobalt, and vanadium) that are currently used in food supplements on sale in the UK. The second list covers the chemical forms (sources) of those vitamins and minerals that may be used. These lists can be added to following a favourable opinion on individual nutrients or nutrient sources from the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) after consideration of a dossier containing safety data.[16] Now, there are two positions on dietary supplements. One is to regard them as useful simply to prevent illnesses caused by deficiencies, like scurvy, beriberi and pellagra. The semi-official recommended daily allowances, which can be seen on every label, are based crudely on the estimated dosage needed to prevent deficiency. On this reasoning, dietary supplements have their use at times and in places where people cannot eat a full and balanced diet. But they are at best useless in wealthy countries like Britain and America, where just about everyone can have all the food he wants to eat. In some cases, they can be dangerous. The other position is to regard dietary supplements as active contributors to health and longevity. The recommended daily allowances are regarded as minimum doses. The full potential of these supplements can only be realised at far higher doses. Linus Pauling, for example who developed the polio vaccine believed that taking very large doses of vitamin C could prevent and in some cases even cure cancer. There is a huge literature or varying quality which suggests that the high, regular intake of certain dietary supplements can prevent or alleviate or cure many other illnesses, and can often achieve better results than the patented medications of the pharmaceutical industry. These are both arguable positions. Given the right environment of diversity, the dispute might long since have been settled by experience. The problem is that, while no compelling evidence has been presented against them, it is widely believed that the pharmaceutical companies have decided that their interests are best served by having the first position imposed by law.

Controls on dietary supplements mean a bigger market for patented medicines than would otherwise exist. They also provide regulatory hurdles that restrict the market to those big pharmaceutical companies able and willing to pay for the necessary certification.

In Partial Defence of the Pharmaceutical Companies

These are serious charges. Not all, however, are justly laid. Much criticism of the pharmaceutical industry seems to proceed from a general hostility to private business. And it seems to be taken for granted that profit is at least an indecent companion to the search for cures and palliatives for human illness. But what other model is there for the development of pharmaceutical products that work? The Soviet and Chinese state pharmaceutical industries never amounted to much in terms of research and development of products that were useful to ordinary people or even useful for their stated purpose. The private companies in the free world at least do create new and useful products. And all this research and development costs money. Taking into account research and development and regulatory compliance, it costs about $800 million to bring a new pharmaceutical product to market.[17] Many of these costs are incurred whether or not the product is actually put onto the market. For every one new product put on the market, 5,000 chemical formulations do not make it: either they do not work as expected or they are outperformed or simply beaten to market by a rival product. Once on the market, they have only a few years of profitability before the patent protection expires, or before an improved product is released by another company. A recent study of 100 pharmaceutical products showed that the profits earned on most of them did not cover investment costs.[18] Therefore, it is entirely reasonable that the pharmaceutical companies should try to make a profit on those products that do come to market.

Parallel Imports

Turning to the issue of parallel imports, this is far most complex than the usual story of greedy pharmaceutical companies and heroic small firms undercutting them. The pharmaceutical companies adopt a strategy of contributive skim pricing. In the richer countries of the developed world, the price of a new product is set far above immediate costs of production, and even above its own development cost. Some part of the resulting surplus may represent profit in the economic sense. In many cases, though, it will be taken as a contribution to the general development costs of the company. In other words, those products that do succeed are priced to cover the costs of developing all products, whether or not successful. This allows pharmaceutical companies to charge lower prices in other countries, where people are too poor to pay the full cost price of pharmaceutical products, but not too poor to buy at any price. In these countries, the pharmaceutical companies set prices to cover marginal cost of production plus whatever contribution to overheads can be charged. Companies distinguish between overheads and marginal costs. Price must always cover the latter, but may include a variable contribution to the former. Prices in poor countries are set to make a small contribution to research and development overheads, and a larger contribution is taken in rich countries. It makes economic sense, though the result is prices are largely determined by ability to pay, and patients in poor countries receive a large indirect subsidy from patients in rich countries. The parallel trade threatens to destroy this subsidy to the poor. If people can buy pharmaceutical products at lower cost abroad, and re-import them, there is a short term fall in price. But the longer term consequences will be a shortage of investment funds for research and development of new products. Therefore, if steps are taken to limit the re-importation of products, these may be open to criticism in their specifics, but are not in themselves immoral business conduct.

How Can the Pharmaceutical Market be Improved?

But while there are defences to some of the charges, there is enough truth in the attack for the pharmaceutical industry to have fallen at least partially into disrepute in recent years. The pharmaceutical industry is seen as greedy, secretive and indifferent to the wishes or even needs of patients. It is also often seen as unable to create products that work effectively and safely. And the evident truth of these charges is being used as an argument for tighter regulation of how the pharmaceutical companies operate. The Consumers Association, for example, believes that the answer to the problems raised above is more and better regulation. In its own submission of August 2004 to the Commons Health Select Committee, it argued The Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) needs to ensure that all its work is undertaken in the interests of public health protection.[19] It further argues: Responsibility for monitoring all forms of pharmaceutical industry advertising and other promotion should be transferred to a new, independent advertising and information regulator. This regulator should adopt and proactively implement robust and transparent procedures to prevent misleading promotional campaigns - including all forms of covert promotion - as far as possible at the outset, and to take swift and effective action when these do occur. These procedures should be drawn up in consultation with all relevant parties, in particular, those representing the interests of patients, consumers and public health. Most importantly, they should maintain a clear focus on protecting public health and delivering public benefit.[20] What reason, however, is there to suppose that regulation really is the solution to any of these problems? Undoubtedly, we live in an age where regulation is seen as the solution to every problem. As in the rest of the English-speaking world, Britain is subject to a heavy and growing weight of regulation. This is not the place to discuss whether any specific regulation is justified. It is enough to say that there is a general assumption among those who matter that everything that is done by the people must be known to the authorities and controlled by them. During the ten years to the 21st February 2005, the phrase completely unregulated occurs 153 times in the British newspaper press. In all cases, unless used satirically, the phrase is part of a condemnation of some activity. We are told that the advertising of food to children,[21] residential lettings agents,[22] funeral directors,[23] rock climbing,[24] alleged communication with the dead,[25] salons and tanning shops,[26] contracts for extended warranties on home appliances,[27] and anything to do with the Internet - that these are all almost completely unregulated or just completely unregulated, and that the authorities had better do something about the fact.

Regulation: Solution or Problem?

Yet is regulation the solution in this case? The assumption behind much of what was presented to or discussed in the Select Committee hearings appears to have been that whatever wrong or merely questionable was done by the pharmaceutical companies could have been avoided by a better scheme of regulation, and that, the problems uncovered, the best use of intellectual effort must now be in devising a better scheme for the future. But what went wrong with the regulations already in place? The answer is that the present regulatory body for the pharmaceutical industry the Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) seems to have been too close to the industry for effective regulation to have taken place. In October 2004, The Guardian newspaper obtained documents that showed the nature of the relationship. Since 1989, when the then prime minister, Margaret Thatcher, took drug regulation out of the hands of the Department of Health, the MHRA has been wholly funded by the pharmaceutical companies. Since then: The regulator and the industry have been engaged in a joint lobbying campaign in Europe; The industry privately drew up its own detailed blueprint of how the MHRA should be run; The industry has been pushing for higher level representation at the MHRA against ministers wishes.[28] John Abraham, professor of sociology at Sussex University, who is mainly known for his books on drug regulation, says that the MHRA has come to believe the interests of public health are coherent with the promotion of the industry. He says: The criticism of the old Department of Health medicines department in the 70s was that it didnt have any teeth. Not only does it now not have any teeth, but it is not motivated to bite.[29] He further claims that there is too much of the revolving door syndrome at the MHRA. Not only does it take fees from the pharmaceutical industry, but many agency officials used to work for pharmaceutical companies, such as the former head of worldwide drug safety at GlaxoSmithKline, who is now the MHRAs head of licensing. It was with these facts in mind that the Consumers Association has called for a new regulatory body. However, what appears to have happened with pharmaceutical regulation is not some aberration that can be improved with a new legal framework. It is no more than the illustration of a general tendency.

The Case for Regulatory Bodies: Asymmetric Information as Market Failure

The justification for a regulatory body where pharmaceutical products are concerned is what economists call market failure. The mainstream defence of the free market rests on the claim that it allocates resources more efficiently than any other system. To speak formally, it tends to bring about both productive and allocative efficiency. This first means that goods and services are produced at the lowest currently known cost. The second means that production satisfies the known wants of consumers in the fullest way currently possible. We can best see this argument in the analysis of firms under perfect competition. Let it be granted: that there are many buyers and sellers in a market; that all the goods produced in this market are of the same quality; that there are no barriers to entry or exit for any player in the market; that there is perfect knowledge among all players in the market regarding prices and production methods. Given these assumptions, an equilibrium between demand and supply will come about that maximises social welfare. Any intervention by the authorities in such a state of affairs will produce a loss of welfare. Now, such an equilibrium never comes about in the real world. It certainly never comes about in the pharmaceutical product market. There are not large numbers of buyers and sellers, nor are goods of the same quality instead, there is a group of very large companies with virtual monopolies in certain products, facing a virtually monopsonistic buyer in each national market: in Britain, this is the National Health Service. There are obvious barriers to entry and exit. Above all, there is not perfect knowledge. There is instead what is called the problem of asymmetric information. The pharmaceutical companies know all that can be humanly known about their products: the consuming public knows almost nothing, and is not thought able to learn what needs to be known. This being so, the overwhelming consensus of opinion is that some regulatory body is needed to stand between the pharmaceutical companies and the consuming public. The functions of this body are to ask the appropriate questions, and only to allow products to be sold if the answers are satisfactory. Given sufficient zeal by or trust in the regulatory body, there is no need for the public to ask its own questions. Indeed, there is a case for the public not to be allowed to find out information for itself. The public may be too ill-informed about the nature of what is being discussed to understand the nature and quality of the information provided especially as much information will come from sources that are themselves ill-informed. Therefore, in this country, the Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency. Therefore also bans on the advertising of pharmaceutical products, and a very tight control over what information can be released to the public. The problems with this restrictive approach is that it does not work. As we have seen, the pharmaceutical companies will seek ways around any controls. They will set up front organisations to campaign for certain products to be made available. They will also place what appear to be academic papers in the medical press that are in effect disguised advertisements, and will heavily promote products directly to general practitioners. They may thereby ensure pressure on regulatory bodies to take a more liberal approach to licensing of products.

The Economics of Regulatory Capture

The main problem with this approach, however, is not incidental by systemic. It is what pubic choice economists call regulatory capture. The phrase comes from Gabriel Kolko, a Marxist historian, who reworked his doctoral thesis into the The Triumph of Conservatism: A Reinterpretation of American History, 1900-1916, published in 1963[30] and followed it up with a more detailed study of a single industry in Railroads and Regulation in 1965.[31] He applied the phrase to a specific phenomenon: when regulators serve the interests of those they are allegedly regulating in the general public interest. It was known before Kolkos work, but regarded as an aberration. Kolko examined the growth of American federal regulation in the early 20th century, and argued that regulatory capture was not just common, but in fact the norm. He found no important exception to its emerging, and usually emerging very early, in the history of a regulatory agency. As the phrase "triumph of conservativism" suggests, Kolko argued that whatever liberal reformers might have intended, and whatever the public may have believed, business interests took control of the actual regulatory process early on and made it work for them.

The basic mechanics of regulatory capture are straightforward. People give more attention to a particular law or agency if they feel that they have something at stake. They will make sure to know about laws and policies that affect their own interests. If those people are running a wealthy business, they will have a lot at stake, and will correspondingly make sure to be fully informed. Now, regulators may at first feel hostile to their subjects. Over time, however, regulators and the regulated get to know each other and to work together, with or without any real sense of cooperation. The regulated, who provide information and make a show of cooperation, earn the appreciation of regulators, who find that endless crusade takes its toll in energy, enthusiasm, and efficiency. Regulators find that if they cooperate with their subjects in some areas, they will get cooperation back on others. In addition, those of the regulated who gain the sympathy of regulators as "team players", "responsible, cooperative enterprises", and the like get favours. The problem is that incremental small shifts can add up to big consequences. Over years and decades, the net effect of such shifts in the course of regulation is to draw the regulatory agency in directions that the public is likely neither to understand nor to feel represents the original intent of the legislation that created the agency. There is no need for regulators and regulated to like each other. Often they do not. They still work together. Regulators hardly ever want to destroy what they regulate. Most often, they see their job as simply a matter of imposing the public interest on otherwise irresponsible organisations. And the regulated usually regard the regulators as facts of life to deal with, and better cooperated with than resisted outright. Regulated firms end up supplying not just data to regulators, but personnel. After all, who understands the field better than folks who are retiring or resigning from the field's major participants? Few people want regulations made in outright ignorance. The result is a regulatory agency staffed by former or perhaps future colleagues of those in the regulated firms. Every so often, incidental details of this process will come to light. See, for example, The Guardian report cited above. Sometimes, the details will verge on the scandalous see, for example, the revelations of the late 1990s about the body set up to regulate the British National Lottery. But the overwhelming evidence is that it is impossible to ensure that the regulators and regulated in any scheme of regulation will not eventually come to regard each other in at least many important respects as allies, and to ensure that regulation works in what objective third parties might regard as the public interest.

Safety in Diversity?

Regulation, then, may not be the solution. Indeed, there may be no overall solution. Anyone who expects new pharmaceutical products to be completely effective and completely safe and the pharmaceutical companies to love their customers more than their balance sheets, is asking for a perfection that cannot be on offer. We are talking about human beings. These have their own interests to consult, and they never know the full consequences of their actions. New pharmaceutical products are usually based on radical new departures in scientific understanding; and it can never be known in advance what will the full effects will be. Testing on animals and on a small number of human volunteers can never give the same knowledge of effects that comes from having a product on the market for several years. Whatever model of supervision we adopt for the pharmaceutical industry, there will inevitably be failures medications that do not work, medications with unacceptable side effects, medications that are a deadly menace to those who take them. It is unrealistic to expect otherwise. Nevertheless, we can hope to improve on the existing situation. The central questions are of information and trust. How can it be generally known which pharmaceutical products work for patients? And how can we trust claims about what does work? Part of the answer at least lies in diversity of information. As said, we live in a world of centralised information about pharmaceutical products. Ordinary people are not expected or fully allowed to learn for themselves about the value of any particular medication. Therefore, information about any specific product is of two kinds. First, there are the impenetrable and often secretive conversations that take place between the pharmaceutical companies and the regulators of the medical profession or both. Second, there are the completely unregulated and frequently unlikely claims that circulate on the Internet some websites, for example, recommend Prozac as an appetite suppressant.[32] Between these extremes, there is at best limited room made for informed debate about pharmaceutical products.

Controlled Release of Information

Much has happened since the high age of confidence in government. But what Douglas Jay a Minister in the Labour Government of the day still largely holds: [I]n the case of nutrition and health, just as in the case of education, the gentleman in Whitehall really does know better what is good for the people than the people know themselves.[33] We have an increasingly complex and dynamic pharmaceutical market in which it has been reasonable to see untrained members of the public as incompetent to make informed choices about products, and we have a medical profession and set of regulatory agencies expected and empowered by law to make their choices for the public. That is why there are presently advertising controls in many European countries. These are now codified in the commercial law common throughout the European Union. Directive 2001/83/EC on the Community code relates to medicinal products for human use. This Directive prohibits the advertising of prescription only medicines to the general public. Indeed, it goes further in suggesting that rules are needed for all pharmaceutical products, whether or not prescribed: Advertising to the general public, even of non-prescription medicinal products, could affect public health, were it to be excessive and ill-considered. Advertising of medicinal products to the general public, where it is permitted, ought therefore to satisfy certain essential criteria which ought to be defined.[34] Even before this blanket prohibition came into force within the European Union, many national jurisdictions had adopted into their product liability laws some variant of the American learned intermediary rule, whereby pharmaceutical suppliers were under a duty to warn only the physician intermediary, not the patient. Such rules essentially immunised the pharmaceutical manufacturer in most failure-to-warn cases. Injured, uninformed patients were expected to proceed against the doctor for negligence, typically for lack of informed consent.[35]

Institutionalised Asymmetric Information

The effect of these regulations is not to protect the public from charlatans. As said, the Internet is already full of charlatans. Their effect is to prevent informed discussion of pharmaceutical issues of a kind that ordinary people can understand. Because the pharmaceutical companies are prohibited by law from communicating directly with the public, the public must trust either what information is transmitted via the medical profession, or the wild claims of Internet salesmen based in the British Virgin Islands. At the same time, the pharmaceutical companies cannot reach out directly; they cannot truly know what their customers want. A system of regulation devised to solve the problem of asymmetric information has set this asymmetricity in legal concrete. Look again at the Internet claims about Prozac as an appetite suppressant. Anyone who thinks it can help with dieting may be misinformed. Whatever the case, Eli Lilly, the manufacturer of the product, is not allowed to publish a word about the correct uses of Prozac. Again, there are websites that denounce the products of the pharmaceutical companies and instead recommend products that may be useless or actually harmful. These products include psychic surgery, faith healing, laetrile, and much else. In 2004, the Journal of Medical Internet Research published a survey of websites providing information on complementary and alternative medicine. The researchers found that: We found that most CAM Web sites were potentially harmful either by displaying statements which could cause harm, or by omitting vital information. However, our data suggest that available technical quality criteria fail to identify potentially harmful information online. We found that one quarter of CAM Web sites present information that may cause physical harm if acted upon. These sites encouraged consumers to avoid conventional therapy, presented information on products that may be directly toxic, or presented information on products that may cause interactions with conventional medications. This is potentially dangerous because consumers have easy access to CAM products online and act upon what they see on the Internet., often do so without the knowledge or advice of clinicians. Almost all (97%) CAM Web sites omitted vital warnings, drug interactions, contraindications, or adverse reactions. This is concerning because many consumers perceive "natural" products as safe. Further, many herbs that may be safe when used alone interact with conventional medications.[36] The pharmaceutical companies are often prevented by law from replying in detail to these claims, and from offering their own opinion about the effectiveness and best use of their own products. Anyone can set up a website to claim that Viagra can cure lung cancer. Pfizer, which developed the product, is not allowed within the European Union to say on its own website how it should best be used. Nor is there legal room for any other organisation independent of Pfizer or the regulators to speak authoritatively to the public.

Let the Public Speak and Decide

We need a regulatory framework within which the pharmaceutical companies can speak directly with ordinary people, and in which ordinary people can tell the companies and each other about the medicines they want, and about what they hope from the medicines that are available. This means no regulatory framework other than that provided by the common law of tort and contract. The modes of regulation presently in place have failed. They cannot be reformed. It is better to scrap them and return to the practice of the past. There should be no control on the advertising and sale of any pharmaceutical product. Adults should be able to wander into a pharmacist and buy whatever they please. Doubtless, most people would continue to consult their doctors - but the advice given would be purely advice, and prescriptions would be purely reminders of that advice. In such a market, the pharmaceutical companies would have to direct their advertising not at small groups of professionals, as at present, but at the final users of their products. The purpose of liberalisation here is to enable the growth of a conversation between producers and consumers. After all, it is frequently hard to tell the difference between commercial and ordinary speech see, for example, those front organisation web sites set up Schering Healthcare and Biogen Ltd. It may be said that people really are not able to know what they want, or to understand the nature of what is offered to them. Whether this is a patronising assumption of superiority is beside the point. What does matter is that it is probably a false belief. Ordinary people may not be able to understand all the scientific details of a new pharmaceutical product, but they are surely able to decide whether it is right for them, and whether it is being offered in the way that they want. It is wrong to assume that an informed decision must rest on full information. Every consumer market in the world is filled with informed consumers who have nothing approaching full information. Hardly anyone in the world knows how a refrigerator works. They still somehow work out what capacity, size and shape and colour of refrigerator they want in their kitchens. Even fewer people know how a mobile telephone works. And yet the average child of ten can explain what he wants from a mobile telephone, and which brand and network come closest to giving that. And these are in markets where no controls exist on what information may be given or exchanged. Informed decisions do not require full information. They require information relevant to the decision. What is relevant depends on what is wanted from a product and on the capacity of individual consumers. These are facts that cannot be known to any outside agency, and cannot be known in advance. We can be sure, however, that, where matters of health or even life itself are concerned, consumers will on the whole make very informed decisions. Anyone who looks at the range of magazines available on consumer electronic products, on the detailed answers within them to questions put by the readers, and on the serious attention these magazines receive from people of apparently limited education, can imagine what would happen were the pharmaceutical market opened to the same public scrutiny and dialogue as any other market. The normal objection to liberalising the market in pharmaceutical products - that large numbers of people would buy recreational drugs and thereby wreck their lives - is not worth discussing. It is not worth discussing because everyone knows that recreational drugs are already freely available to anyone inclined to break a few barrely-enforced laws.

http://books.google.co.in/books?id=hlQ56RuhSuAC&pg=PA254&dq=pharma+management+biren+shah +export&hl=en&sa=X&ei=5YKeT6DQBorJrAeCvqBh&ved=0CEEQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q&f=false

http://books.google.co.in/books?id=hlQ56RuhSuAC&pg=PA254&dq=pharma+management+biren+shah +export&hl=en&sa=X&ei=5YKeT6DQBorJrAeCvqBh&ved=0CEEQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q&f=false

You might also like

- Formulation and Invitro Evaluation of Salbutamol Sulphate in Situ Gelling Nasal Inserts. Aaps Pharm. Scitech. 2013,14, (2), 712-718Document1 pageFormulation and Invitro Evaluation of Salbutamol Sulphate in Situ Gelling Nasal Inserts. Aaps Pharm. Scitech. 2013,14, (2), 712-718HimNo ratings yet

- Chiral ChromatographyDocument4 pagesChiral ChromatographyHimNo ratings yet

- Validation of Compressed Air Introduction: Compressed Air Has Wide Applications in Various Industries. in Pharmaceutical IndustryDocument1 pageValidation of Compressed Air Introduction: Compressed Air Has Wide Applications in Various Industries. in Pharmaceutical IndustryHimNo ratings yet

- PurposeDocument1 pagePurposeHimNo ratings yet

- Tem Intro PDFDocument12 pagesTem Intro PDFHimNo ratings yet

- 15707Document8 pages15707HimNo ratings yet

- DrugDocument8 pagesDrugHimNo ratings yet

- List of National and International Journal With Impact FactorDocument2 pagesList of National and International Journal With Impact FactorHimNo ratings yet

- DrugDocument8 pagesDrugHimNo ratings yet

- Articles For Liposome and Microsphere Formulation of MigraineDocument1 pageArticles For Liposome and Microsphere Formulation of MigraineHimNo ratings yet

- NERVOUS MnemonicsDocument4 pagesNERVOUS MnemonicsHimNo ratings yet

- Flavorants 1Document8 pagesFlavorants 1HimNo ratings yet

- Nano Gel 1Document1 pageNano Gel 1ashishhusmsNo ratings yet

- Easy Way To Determine R, S ConfigurationDocument11 pagesEasy Way To Determine R, S ConfigurationHimNo ratings yet

- 4.87 M. Pharm PDFDocument72 pages4.87 M. Pharm PDFHimNo ratings yet

- Chromatography techniques for pharmaceutical compound separationDocument44 pagesChromatography techniques for pharmaceutical compound separationHimNo ratings yet

- Pharmaceutical AidsDocument1 pagePharmaceutical AidsHimNo ratings yet

- Vitamin ChartDocument5 pagesVitamin ChartHimNo ratings yet

- Chapter 10, CBSDocument46 pagesChapter 10, CBSHimNo ratings yet

- Bpharm Final Year Syllabus Mumbai UnivDocument21 pagesBpharm Final Year Syllabus Mumbai UnivHArsh ModiNo ratings yet

- All Anti Buotics Word FormetDocument9 pagesAll Anti Buotics Word FormetHimNo ratings yet

- Best GuidelinesDocument0 pagesBest GuidelinesHimNo ratings yet

- B. PharmaDocument2 pagesB. PharmaHimNo ratings yet

- 3236 91143 Test Organism For Assay of DrugsDocument1 page3236 91143 Test Organism For Assay of DrugsHimNo ratings yet

- Dissolution ApparatusDocument29 pagesDissolution ApparatusGANESH KUMAR JELLA75% (4)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5784)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Nama: Stevany Ayuningsi Aduga Nim: 150600 Kelas: Keperawatan B Questioning To Fill in Pain Assessment Form ObjectivesDocument8 pagesNama: Stevany Ayuningsi Aduga Nim: 150600 Kelas: Keperawatan B Questioning To Fill in Pain Assessment Form ObjectivesAnathasya SalamatNo ratings yet

- 2008 Polyflux R Spec Sheet - 306150076 - HDocument2 pages2008 Polyflux R Spec Sheet - 306150076 - HMehtab AhmedNo ratings yet

- Format OpnameDocument21 pagesFormat OpnamerestutiyanaNo ratings yet

- Toxoplasma Gondii.Document21 pagesToxoplasma Gondii.Sean MaguireNo ratings yet

- List of AntibioticsDocument9 pagesList of Antibioticsdesi_mNo ratings yet

- OSCE Station 1 Diabetic LL ExamDocument5 pagesOSCE Station 1 Diabetic LL ExamJeremy YangNo ratings yet

- SilosDocument3 pagesSilosapi-548205221100% (1)

- 142 DefinitionsssDocument7 pages142 DefinitionsssAnonymous vXPYrefjGLNo ratings yet

- Question 1Document25 pagesQuestion 1Anonymous 1T0qSzPt1PNo ratings yet

- Therapeutic and Toxic Blood Levels of Over 800 DrugsDocument28 pagesTherapeutic and Toxic Blood Levels of Over 800 DrugsAndreia AndreiutzaNo ratings yet

- Clean Versus Sterile Management of Chronic WoundsDocument3 pagesClean Versus Sterile Management of Chronic WoundsDon RicaforteNo ratings yet

- Fraktur DentoalveolarDocument25 pagesFraktur DentoalveolarfirmansyahddsNo ratings yet

- Common Oral Lesions: Aphthous Ulceration, Geographic Tongue, Herpetic GingivostomatitisDocument13 pagesCommon Oral Lesions: Aphthous Ulceration, Geographic Tongue, Herpetic GingivostomatitisFaridaFoulyNo ratings yet

- Certification of Health Care Provider For Family MBRDocument4 pagesCertification of Health Care Provider For Family MBRapi-241312847No ratings yet

- Patient Discharge SummaryDocument1 pagePatient Discharge SummaryampalNo ratings yet

- Friesen C4ST Amended Input HC Safety Code 6 - 140 Omitted Studies 224pDocument224 pagesFriesen C4ST Amended Input HC Safety Code 6 - 140 Omitted Studies 224pSeth BarrettNo ratings yet

- BPH Zinc GreenTea Papaya LeafDocument13 pagesBPH Zinc GreenTea Papaya Leafteddy_shashaNo ratings yet

- Blood Culture Manual MT - SinaiDocument41 pagesBlood Culture Manual MT - SinaiAvi Verma100% (1)

- CIPD FactsDocument2 pagesCIPD FactsStephen BowlesNo ratings yet

- The Medical Research Handbook - Clinical Research Centre PDFDocument96 pagesThe Medical Research Handbook - Clinical Research Centre PDFDaveMartoneNo ratings yet

- Unit Assessments, Rubrics, and ActivitiesDocument15 pagesUnit Assessments, Rubrics, and Activitiesjaclyn711No ratings yet

- Hepatopulmonary Syndrome (HPS)Document2 pagesHepatopulmonary Syndrome (HPS)Cristian urrutia castilloNo ratings yet

- Tricorder X PrizeDocument4 pagesTricorder X PrizemariaNo ratings yet

- Ob-Ch 10Document53 pagesOb-Ch 10Nyjil Patrick Basilio ColumbresNo ratings yet

- Katz Activities of Daily LivingDocument2 pagesKatz Activities of Daily LivingGLORY MI SHANLEY CARUMBANo ratings yet

- O&G Off-Tag Assesment Logbook: Traces-Pdf-248732173Document9 pagesO&G Off-Tag Assesment Logbook: Traces-Pdf-248732173niwasNo ratings yet

- Monograph GarlicDocument2 pagesMonograph GarlicJoann PortugalNo ratings yet

- Clean Room SpecificationsDocument2 pagesClean Room SpecificationsAli KureishiNo ratings yet

- Autism Spectrum DisorderDocument14 pagesAutism Spectrum DisorderAngie McaNo ratings yet

- StreptokinaseDocument2 pagesStreptokinasePramod RawoolNo ratings yet