Professional Documents

Culture Documents

CVA

Uploaded by

ssha_szaimiOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

CVA

Uploaded by

ssha_szaimiCopyright:

Available Formats

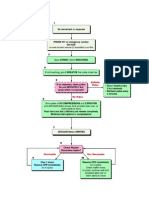

CARDIOVASCULAR ACCIDENT (STROKE) Large Artery Small art (lacunar) infarct <15mm in diameter Sinovenous thrombosis Vascular dissect

w thrombus propagatn Hemodynamic Mechanical obstruct Cardiogenic Aortic arch atheromata Artery-to-artery

Thrombotic ischaemic Causes Embolic Arteritis Spontans Intracerebral Hemorrhage Aneurysmal rupture Bleeding AVM Major risk factors

Hemorrhagic

Minor risk factors

Risk factors

Age Sex Race Genetic predisposition Hypertension: Reduction of diastolic pressure by 5-6 mmHg reduces the risk of stroke by 40%. For isolated hypertension (systolic BP greater than 160 mmHg and diastolic less than 90 mmHg), reducing the systolic BP by 10 mmHg reduces the risk of stroke by 36%. Diabetes mellitus AMI with thrombus Peripheral vascular disease Cigarette smoking Valvular heart disease Hyperhomocysteinemia AF Dilated cardiomyopathy Aortic arch atheromata Hypercoagulable state TIA & prior stroke Ischaemic Thrombotic Premonitory TIA Stepwise progression Evidence o atherosclerotic d/s (angina, IC) Large artery or small artery territory infarctn pattern

Hypercholesterolaemia OCP Migraine Obesity Physical inactivity Mitral valve prolapsed Patent foramen ovale Bacterial endocarditis Marantic endocarditis Sick sinus syndrome Polycythaemia Thrombocythaemia Bleeding diathesis Sympathomimetic agents

Hemorrhagic Embolic Sudden onset o maximl deficit Cardiogenic source o embolus Multiple vascular territory involvmnt Potential assoctn w syncope at onset Potential assoctn w seizure at onset Greater likelihood o hemorrhagic infarct

Types

Branch occlusion infarct pattern Embolic involvmnt o other organs Severe deficit at onset followed by rapid resolutn

History

The nature of the complaint e.g. monocular blindness will guide the clinician toward the anatomical location of the stroke. The onset of the complaint- a sudden or abrupt onset is characteristic of ischaemic stroke. Hemorrhhagic stroke has a more gradual onset over hours or few days Associated symptoms such as chest pain, palpitations, sudden blood loss (e.g. massive haematemesis), may suggest an "extracranial" cause of stroke Past medical history of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, IHD, hyperlipidaemia and TIA Drug history is crucial Social habits including cigarette smoking, alcohol consumption, diet and physical activity Full neurological examination General examinationVital signs particular attentn to CVS- all pulses must be palpated and assessed for rhythm, vessel wall character and volume, the carotids auscultated for bruits, and the heart examined for evidence of cardiomegaly, double apical impulse (left ventricular aneurysm), murmurs and added heart sounds (valvular heart disease and myxomas), stigmata of hyperlipidaemia Pupils- Argyll Robertson pupil Palpate s/f temporal arteries (giant cell arteritis) Clinical features that are caused by anterior circulation (carotid artery) stroke, and b) those caused by posterior circulation (vertebrobasilar system) stroke: Due to anterior circulation stroke Homonymous hemi- or quandrantonopia Dysphasia Hemiparesis/plegia Hemisensory loss/ disturbance Parietal lobe dysfunction e.g. astereognosis, agraphaesthesia, impaired two-point discrimination, sensory and visual inattention, left-right dissociation and acalculia Due to posterior circulation stroke Homonymous hemianopia Cortical blindness Ataxia Dysarthria Diplopia Dysphagia Horner's syndrome Hemiparesis or hemisensory loss contralateral to the cranial nerves palsy

PE

Ac stroke syndromes w vascular territories correlation Artery involved Syndrome Motor and/or sensory deficit (foot>>face, arm) Frontal signs (primitive reflexes, apathy, mutism, disinhibition) Gait apraxia Aphasia, acalculia (dominant hemisphere) Motor & sensory deficit (face, arm > leg) Complete hemiplegia if internal capsule involved Homonymous hemianopia Eye deviation to normal limb Hemineglect (non dominant hemisphere) Homonymous hemianopia Alexia without agraphia

ACA

MCA

PCA

VBA

Penetrating vessels (lacunar syndrome <1.5mm)

Sensory aphasia Visual perception deficit (agnosia), visual hallucination (visual cortex) Hemisensory loss, choreoathetosis, spontaneous pain (thalamus) rd 3 nerve palsy, hemiparesis, vertical gaze palsy (midbrain Cranial nerve palsies Crossed sensory deficit Diplopia, vertigo, nausea, vomiting, dysarthria, dysphagia, hiccup Ataxia, coma Eye deviation to affected limb Pure motor hemiparesis Pure sensory deficit Pure sensori-motor deficit Ataxic hemiparesis Dysarthria clumsy hand syndrome

Aims: 1. Confirming the diagnosis and excluding treatable differential diagnoses. 2. Confirming the nature and size of the stroke 3. Determining the size/extent of the stroke; and 4. Identifying new, and assessing pre-existing, Non contrast CT (primary role to exclude hemorrhage. Infarct can b seen after 6hrs, but no need to wait) MRI- if lesion CT shows no finding & lesion is suspected in brain stem ECG, CXR FBC, PT, APTT, INR RP RBS, lipid profile ABG if pt hypoxic Cardiac enzymes (CK, AST, LDH)- if MI suspected Contrast-enhanced CT brain scan, MRI brain, carotid/vertebral duplex scan, transcranial Doppler US, echocardiogram, blood culture, LP ESR, VDRL, syphilis serology, HIV testing, ANA, stress ECG, bleeding time, platelet f(x) studies, special clotting factor studies, fasting lipid profile, fasting homocysteine level, Thrombophilia screen (protein C & S levels, antithrombin III level) antiphospholipid antibodies, , cerebral arteriography, spiral CT angiography, sickle cell prep

IX First tier

Second tier Third tier

Dx

The diagnosis should provide answers to the following questions: 1. What is the neurological deficit? 2. Where is the lesion? In what arterial territory is the lesion? 3. What is the lesion? 4. What stage is the lesion? How big the lesion is (influences Px)? 5. Why has the lesion occurred? Could it be anything else? 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Resuscitate. This is the first step of stroke management. And this is especially crucial in the drowsy and comatose patients. 4 hourly vital signs Pressure sores: 2 hourly turning and early usage of high quality ripple mattress could prevent. Conscious patients should be nursed in a prop-up position. Head end of the bed elevated to 20-30 degrees. This is a simple measure to reduce venous pressure and thereby reduce intracranial pressure Patient may require urinary catheter or condom drainage to monitor intake and output accurately.

Mx

6.

Avoidance of aggressive BP control in acute ischemic stroke. No urgency to treat moderate BP elevation as it will normalise or return to baseline over a week although a third of them remain hypertensive. A slightly higher systemic BP is required to maintain the cerebral perfusion in the situations of increased ICP, partial thrombosis and disturbed cerebral autoregulation. Treatment of hypertension should be delayed for several days or up to two weeks after a stroke unless there is hypertensive encephalopathy, heart failure, cardiac ischaemia, aortic dissection, continued intracerebral bleeding or severe hypertension (mean BP > 130mmHg or systolic BP > 220 mmHg). 7. Transient stress-related hyperglycaemia occurs after stroke. Mildly elevated blood glucose is usually not deleterious. There is general agreement to recommend control of hypoglycaemia and hyperglycaemia after stroke. In a known diabetic patient, the best policy is to continue the current medications and avoid extreme hypoglycaemia. A short course of insulin therapy may be necessary in the very ill and difficult cases Avoidance o glucose or dextrose-containing IV fluid in acute ischemic stroke 8. Assessment o swallowing capacity initially be given intravenous fluids and commenced on nasogastric tube feeding when neurologically stable. Fluid replacement of 2 litres daily is usually sufficient. Short-term use of nasogastric tube feeding for 4-6 weeks is suggested if the patient still has dysphagia. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tube may be considered if the patient has poor prognosis for regaining an adequate and safe swallowing mechanism 9. Raised ICP: The goal of treatment is to reduce ICP, maintain adequate cerebral perfusion and avoid brain herniation. Factors exacerbating raised ICP which include fluid overload hypoxia, hypercarbia and hyperthermia should be avoided. Hypoosmolar fluid e.g. 5% dextrose may worsen the cerebral oedema. Avoid acute elevation of serum osmolarity of more than 20 mosm above the patient's usual level to prevent precipitating encephalopathy. Hyperventilation reduces the blood carbon dioxide concentration by 5-10mmHg and results in lowering the ICP by 25-30%. This effect can be almost immediate. Hyperosmolar agents e.g. glycerol or mannitol have been used to reduce the ICP. The regime usually followed is 20% mannitol 0.25-0.5g/kg intravenously over 20 minutes and then, if necessary, repeated every 6 hours with the maximum daily dose of 2g/kg. The complications include rebound cerebral oedema, renal failure, fluid and electrolyte imbalance, cardiogenic pulmonary oedema and hypersensitivity. 10. Seizure- Quick termination of seizure is indicated using intravenous diazepam. Subsequently the patient requires a period of therapy with anticonvulsant agents. Seizures occurring more than once should be treated as stroke related epilepsy and managed with the appropriate anticonvulsant agents such as carbamazepine, phenytoin, sodium valproate or other agents Antihypertensives Statin agents Agents to lower homocysteine level Antipatelet agents Aspirin Ticlopidine Clopidogrel Anticoagulants Heparin warfarin Ramipril, perindopril w diuretic Pravastatin, simvastatin Folic acid, vit B6, vit B12 Aspirin, clopidogrel Should be started as soon as possible after the onset of ischaemic stroke, preferably within 48 hours A reasonable approach would be to commence the patient on 300mg on day one, followed by 150mg daily subsequently

IV rtPA

LMW heparin (Nadoprin) given in the dosage of 4100 IU twice daily subcutaneously within 48 hours from the onset of the acute ischaemic stroke for 10 days was effective in improving outcomes (deaths and dependency) at six months. Oral anticoagulant (warfarin) can be started one week from the stroke, since the chances of a recurrent stroke within a week from these conditions are relatively low. The level of anticoagulation should be aimed between INR2-2.5 for those with atrial fibrillation and slightly higher for those with prosthetic cardiac valves. 0.9mg/kg with a maximum of 90mg is the recommended treatment for patient presenting within 3 hours of onset of ischaemic stroke. 10% of the dose is given as a bolus, followed by an infusion lasting 60 minutes.

Recommendations for initiating thrombolytic treatment 1) If a CT brain demonstrates early changes of a recent major infarction, oedema, or possible haemorrhage, thrombolytic therapy should be avoided. 2) The risk and potential benefits of rtPA should be discussed whenever possible with the patient and family before treatment is initiated. 3) The patient needs close observation, frequent neurological assessments and cardiovascular monitoring. 4) Central venous access and arterial punctures are restricted during the first 24 hours. 5) Placement of an indwelling bladder catheter should be avoided during the period of infusion and for at least 30 minutes following the end of the infusion. 6) Insertion of a nasogastric tube should be avoided if possible during the first 24 hours after treatment. 7) Person given intravenous rtPA should not receive aspirin, heparin, warfarin, ticlopidine, or other antithrombotic or antiplatelet aggregating drugs within 24 hours of treatment Indication Contraindication Acute ischemic stroke presentation & Rx possible Hemorrhage on CT brain w/in 3hrs Uncontrolled HPT w SBP >185mmHg and/or DBP > Persistent significant neurologic deficit on repeat 110mmHg examintn Hx o intracranial hemorrhage Absence of signfcnt imprvmnt on serial examintn Thrombocytopenia w platelet count < 100 000 uL Absence o marked anemia, severely abN blood Active anticoagulant therapy glucose level or other severe metblc disturbance or Actie internal bleeding bleeding diathesis by lab Ix Recent serious head trauma, recent prior ischaemic No assoctd seizure activity at onset stroke or recent intracranial surgery No recent arterial or LP Clinical suspicion for SAH Management of bleeding complications 1) STAT head CT, if ICH is suspected 2) Consult neurosurgery for ICH 3) Check FBC, PT, PTT, platelets, fibrinogen & D-dimer. Repeat q 2hr until bleeding is controlled 4) Give FFP 2 units every 6hr for 24hr after dose 5) Give cryoprecipitate 20units. If fibrinogen level <200mg/dl at 1hr, repeat cryoprecipitate dose 6) Give platelets 4 units 7) Give protamine sulphate 1mg per 100U heparin received in last 3hr (give initial 10mg test dose slow IV over 10 mins & observe for anaphylaxis. If stable gice ntire calculated dose slow IV, max 50mg) 8) Institute frequent neurological checks & therapy of an acutely raised ICP 9) May give aminocaproic acid 5g in 250ml NS over 1hr as a last resort Protocol for BP control after IV rtPA for acute stroke Pt should be admitted to ICU for 24hrs,monitor with noninvasive BP cuff unless sodium nitroprusside is used Every 15 min for 2hr Every 30min for 6hr Every 60min for 24hr BP 2 reading 5-10 mins Mx apart 180-230/105-120 mmHg IV labetolol 10mg over 1-2mins. Dose may b repeated or doubled every 10-20min up to 150mg >230/121-140 mmHg IV labetolol 10mg over 1-2mins. Dose may b repeated or doubled every 10-20min up to 150mg

DBP >140 mmHg

If no satisfactory response, infuse sodium nitroprusside (0.5-10g/kg per minute) If no satisfactory response, infuse sodium nitroprusside (0.5-10g/kg per minute)

Cx

Assesment for evidence of post stroke depression Long-term management of risk factors for stroke Raised intranial pressure (ICP): The peak incidence is 3-5 days post infarct. This is a common cause of death in the first week of stroke. It is a complication of occlusion of major intracranial arteries and large multilobar infarcts and may be fatal in the first 24-48 hours. Only 10%-20% of cerebral oedema warrants medical interventions. These patients show signs of raised ICP such as deteriorating GCS (Glasgow Coma Scale), clinical features of herniation e.g. pupil enlarging ipsilateral to the infarcted hemisphere or pathological corticospinal signs contralateral or ipsilateral to the hemispheric lesion. Seizure: Seizure in the first 2 weeks of stroke occurs in 4-8% of patients, being more common in frontal lobe infarctions. The seizures are localization related and may remain partial (nonconvulsive) or may progress to become generalise.

Primary prevention

Modifying risk factors Recurrent strokes occur in 15-40% of survivors Can be prevented by modifying risk factors Aspirin reduces the relative risk of stroke or death by about 20% per year after transient ischaemic attack (TIA) or minor ischaemic stroke. Ticlopidine, clopidogrel and dipyridamole in combination with aspirin have all been shown to be more superior to aspirin for secondary prevention of stroke. Warfarin is used to prevent stroke due to atrial fibrillation, valvular heart disease and if there is evidence of a thrombus in the left ventricle. In patients with TIA or minor stroke not due to valvular heart disease, warfarin reduces the relative risk of recurrent stroke by 70%. The recommended INR level is 2-3. The rehabilitation process invovles six major areas: 1. Preventing, recognizing and managing co-morbid illness and medical complications 2. Training for maximum independence 3. Facilitating maximum psychological coping and adaptation by patient and family 4. Preventing secondary disability by promoting community integration, including resumption of home, family, recreational and vocational activities 5. Enhancing quality of life in view of residual disability. 6. Preventing recurrent stroke and other vascular conditions such as myocardial infarction that occur with increased frequency in patients with stroke Rehabilitation can be looked at in two aspects: I. The process of rehabilitation II. The aim or end-point of rehabilitation I. The process of rehabilitation Assessment Identification and measurement of problems. Analyse the cause Planning Goal-setting Identify aims, objectives and targets Aims = set at level of handicap Objectives = describe in terms of changes in level of disability Target = described in terms of specific abilities to be achieved Intervention Therapy to influence change (recovery)

Secondary prevention

Stroke rehab

Care to maintain status quo Evaluation Reassessment II. The aim or end-point of rehabilitation To maximise the patient's role fulfillment and independence in his environment, all within limitations imposed by the underlying pathology and impairments and by availability of resources. To help the person make the best adaptation possible. FIRST STEP Assessment Identify areas of difficulty Underlying causes (impairments, pathologies) Prognostic factors relating to natural history and successful interventions SECOND STEP Match the patient with the appropriate rehabilitation services and setting THIRD STEP Identify aims and set goals Agree on time frame Realistic short-, intermediate- and long-term goals FOURTH STEP Continuous assessment and evaluation Have goals been achieved Have new problems appeared?? Identify and act Why have the goals not been met?? Reset the aims and expectations of the patient and family

Subarachnoid hemorrhage Causes Causes of SAH 1. Rupture of intracranial (usually Berry) aneurysm (75%) 2. AVM (5%) 3. Unknown (20%) 4. Bleeding diathesis 5. Cx o anticoagulant therapy 6. Illicit drug use e.g cocaine 7. Mycotic aneurysm 8. Hemorrhagic metastasis 9. Bleeding into primary brain tumor 10. Bleeding into brain abscess 11. Arteritis 12. Amyloid angiopathy 13. Hemorrhagic leukoencephalopathy Sudden onset of severe headache, LOC, meningism, vomiting, retinal hemorrhage (subhyaloid hemorrhages), seizure, ECG abN (T inversion, ST changes, U wave, QT prolongation) Neurlogical deficit related to site of aneurysm & size of hemorrhage Cx of SAH include rebleeding (20% at 2 weeks), vasospasm w ischemia (day 4-14), hydrocephalus, seizures, SIADH World Federation of Neurologic Surgeon Grade GCS Focal Neurological Deficit Grade I 15 Absent Grade II 14-13 Absent Grade III 14-13 Present Grade IV 12-7 Present or absent Grade V 6-3 Present or absent General ix as cerebral infarct CT/ MRI LP should b performed when clinical impression of SAH is not confirmed Angiography is needed if surgery is contemplated General care Resuscitation Sedation with phenobarbitone or diazepam to prevent excitement or elevation of BP without compromising GCS Phenytoin loading dose 15mg/kg to prevent seizure Treat nausea & vomiting Oxygen, prevention of gastric erosion Stool softeners BP control if DBP 120mmHg Prevention of vasospasm: Nimodipine 30-60mg PO 4hrly for 3 weeks initiated within 4 days of presentation. If IV Nimodipine available, give infusion for 5-14 days followed by oral for 7 days. Start 1mg/hr for 2 hr, then increase after 2 hr to 2mg/hr if it is tolerated. Pt whose body weight <70kg or labile BP should be started with dose 0.5mg/hr. Should be administered as continuous IV infusion via 3 way catheter with 40ml/hr D5% or NS through central catheter using infusion pump. Definitive Rx 1. Early Surgery-clipping neck of aneurysm. Prevents rebleeding Allow for triple H therapy (hypervolaemic, hypertensive, hemodilution) to be instituted 2. ENdovascular occlusive procedure- embolization with platinum coils In patient contraindicated for surgery or with surgically unclippable aneurysm Further bleeding is more frequent 1. Vasospasm 2-3 days after hemorrhage and peak at Day 7. Confirmed by transcranial Doppler or cerebral angiogram. Most consistently effective Rx are i. hypervolemia Administer 5% albumin or artificial colloids. Monitor CVP, maintain between 8-12cmH20 or PCWP 1216cmH2O ii. and/or induced arterial hypertension Raise BP with inotropic agents eg IV Dopamine, dobutamine, keep MAP at 110mmHg 2. Rebleeding 3. Hydrocephalus Ventriculostomy by EVD (Extraventricular Drainage) or shunt Repeated LP can also be done to Rx communicating hydrocephalus 4. Seizure 5. Cerebral oedema

C/F

Grading

Ix

Mx

Cx

You might also like

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Booklet Bcu Revisi 5Document8 pagesBooklet Bcu Revisi 5irza nasutionNo ratings yet

- HypertensionDocument36 pagesHypertensionRECEPTION AND DIAGNOSTIC CENTER RDC MEDICAL SECTIONNo ratings yet

- Development of A Wireless Blood Pressure Monitoring System by Using SmartphoneDocument4 pagesDevelopment of A Wireless Blood Pressure Monitoring System by Using SmartphoneSagor SahaNo ratings yet

- Lesson 10 Long Term Effects of ExerciseDocument11 pagesLesson 10 Long Term Effects of ExerciseMaliha RiazNo ratings yet

- Understanding Blood PressureDocument9 pagesUnderstanding Blood PressurePrasanna DissanayakeNo ratings yet

- Balancing Prana Vayu and Apana Vayu - SivaSaktiDocument6 pagesBalancing Prana Vayu and Apana Vayu - SivaSaktisugumarjeNo ratings yet

- DR - Jetty - Executive Summary of Perioperative ManagementDocument28 pagesDR - Jetty - Executive Summary of Perioperative ManagementDilaNo ratings yet

- Broda Barnes Solved Riddle Heart AttacksDocument47 pagesBroda Barnes Solved Riddle Heart AttacksArsalan Khan100% (1)

- NCLEX Mark K NotesDocument131 pagesNCLEX Mark K NotesRhika Mae ObraNo ratings yet

- American Heart Association Acls Post Test AnswersDocument4 pagesAmerican Heart Association Acls Post Test AnswersArun Jude Alphonse0% (9)

- 10 Scientifically Proven Health Benefits of Taking A BathDocument6 pages10 Scientifically Proven Health Benefits of Taking A BathKiara Isabel Dela VegaNo ratings yet

- Guyton and Hall Textbook of Medical Physiology 13e PDFDocument1,046 pagesGuyton and Hall Textbook of Medical Physiology 13e PDFhanifah karim100% (56)

- AVIATION Flight Physiology: - Kirk Michael WebsterDocument56 pagesAVIATION Flight Physiology: - Kirk Michael WebsterabriowaisNo ratings yet

- ABCDE Assessment - Lecturio PDFDocument11 pagesABCDE Assessment - Lecturio PDFjsw03No ratings yet

- Nursing Care Plan For HypertensionDocument4 pagesNursing Care Plan For HypertensionKathleen Dimacali100% (2)

- Normal Electrocardiogram: Lucia Kris Dinarti Cardiology Department Faculty of Medicine GMUDocument21 pagesNormal Electrocardiogram: Lucia Kris Dinarti Cardiology Department Faculty of Medicine GMUMuhammad Ricky RamadhianNo ratings yet

- Cir 0000000000001054Document16 pagesCir 0000000000001054Code ValmirNo ratings yet

- Human Fetal Circulation For NursingDocument21 pagesHuman Fetal Circulation For NursingHem KumariNo ratings yet

- Estimation of Sterols in Edible Fats and Oils (Sabir Et Al., 2003)Document4 pagesEstimation of Sterols in Edible Fats and Oils (Sabir Et Al., 2003)Pankaj ParmarNo ratings yet

- Sikkim University: Rules & Syllabus For The Bachelor of Pharmacy (B. Pharm) CourseDocument147 pagesSikkim University: Rules & Syllabus For The Bachelor of Pharmacy (B. Pharm) CourseVikash KushwahaNo ratings yet

- Touchcardio HRC Abstracts 2022 Final 3Document149 pagesTouchcardio HRC Abstracts 2022 Final 3Cristina AdamNo ratings yet

- Machine Learning and Iot For Prediction and Detection of StressDocument5 pagesMachine Learning and Iot For Prediction and Detection of StressAjj PatelNo ratings yet

- Frequency DR Hulda Clark ZapperDocument45 pagesFrequency DR Hulda Clark ZapperkwbutterfliesNo ratings yet

- Autopsy Report For Damon WeaverDocument9 pagesAutopsy Report For Damon WeaverGary DetmanNo ratings yet

- ECG NotesDocument85 pagesECG NotesMalcum TurnbullNo ratings yet

- Ant Internal Anatomy DiagramDocument4 pagesAnt Internal Anatomy DiagramHfNo ratings yet

- Tai Chi ChuanDocument89 pagesTai Chi Chuandani100% (1)

- Magnet Space Materijal ENGDocument40 pagesMagnet Space Materijal ENGIvana MilosavljevicNo ratings yet

- Basic Life SupportDocument6 pagesBasic Life SupportRyan Mathew ScottNo ratings yet

- Writing NocnDocument19 pagesWriting NocnMarianna PapNo ratings yet