Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Suicide Prevention Europe

Uploaded by

dariusturc792Original Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Suicide Prevention Europe

Uploaded by

dariusturc792Copyright:

Available Formats

Suicide prevention

I actually thought that Wendy was getting a little better and that all she had to do was stick it out. I now realise that it is at this very point that people are at their most vulnerable. They have a little energy and can see where they are and, of course, it is light years away from where they want to be. It all seems so hopeless to them and it did to Wendy as she said in her note.

(Widower, personal communication to Technical Officer, Mental Health, WHO Regional Office for Europe)

Facing the challenges

Suicide is not only a personal tragedy, it represents a serious public health problem, particularly in the WHO European Region. From 1950 to 1995 the global rate of suicide (for men and women combined) increased by 60% (1). Among young and middle-aged people, especially men, suicide is currently a leading cause of death. According to the latest available data, an estimated 873 000 people around the world, and 163 000 in the European Region, die from suicide each year (2). While suicide was reported to be the thirteenth leading cause of death globally, it was the seventh leading cause of death in the European Region. The highest rates in the European Region are also the highest in the world.

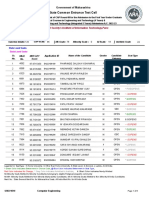

preventive measures are put in place. In countries in the European Region, the average suicide rate is 17.5 per 100 000 population. The mortality supplement to the WHO Health for All database for the latest available year (4) shows that the rates vary considerably in the Region, from 44.0 in Lithuania, 36.4 in the Russian Federation or 33.9 in Belarus, to 5.9 in Italy, 4.6 in Malta or 2.8 in Greece. The gap between the newly independent states of the former Soviet Union (NIS) and European Union (EU) countries is 15.8 per 100 000 population. There are also huge differences between the genders for all age groups. In Lithuania, for instance, 81.7 out of every 100 000 men commit suicide compared with 11.5 women; corresponding figures in Kazakhstan are 58.8 and 9.1, and in Latvia 48.8 and 10.4.

A problem on the rise

There is an increase in mental disorders and selfdestructive behaviour in both poor and rich countries (3). All predictions show that a dramatic increase in suicidal behaviour is to be expected in the coming decade unless effective In the European Region, in the age group 1535 years, suicide is the second most common cause of death after traffic accidents.

Social impact and economic costs

The psychological, social and Suicide and financial impact of suicide on attempted suicide the family and society is result in major immeasurable. On average, a economic losses. single suicide intimately affects at least six people. If a suicide occurs in a school or workplace, it has an impact on hundreds of people.

EUR/04/5047810/B7 29 October 2004

EUR/04/5047810/B7 page 2

Besides the direct loss of life, there is the longlasting psychological trauma of family and friends, and the loss of economic productivity for society. The burden of suicide can be estimated in DALYs (disability-adjusted life years). In 2002, selfinflicted injury was responsible for 1.4% of the total burden of disease worldwide (2) and for 2.3% of the burden in the European Region. Direct costs reflect treatment and hospitalization following suicide attempts, and indirect costs represent potential lifetime income lost due to suicide-related disability and premature death.

Protective factors are related to emotional wellbeing, social integration through participation in sport, church associations, clubs, etc., connectedness with family and friends, high selfesteem, physical and environmental aspects such as good sleep, a balanced diet, physical exercise and a drug-free environment, as well as various sources of rewarding pleasure.

Building solutions

In response to this serious public health problem, substantial efforts have been made in many countries to prevent suicide (5). WHO has produced an updated inventory of national strategies for suicide prevention in WHOs European Member States (6). At a WHO meeting on suicide prevention strategies in Europe, held in Brussels on 11 and 12 March 2004, health policy-makers and experts in mental health and suicide behaviour from 36 Member States in the European Region discussed current evidence and practices in suicide prevention and formulated recommendations for suicide prevention strategies. The conclusions of the meeting can be summarized as follows:

Risk factors

Suicidal behaviour has a large number of underlying causes. It is associated with a complex array of factors that interact with each other and place individuals at risk. These include:

psychiatric factors such as major depression, schizophrenia, alcohol and other drug use, and anxiety disorders; biological factors or genetic traits (family history of suicide); life events (loss of a loved one, loss of a job); psychological factors such as interpersonal conflict, violence or a history of physical and sexual abuse in childhood, and feelings of hopelessness; social and environmental factors, including availability of the means of suicide (firearms, toxic gases, medicines, herbicides and pesticides), social isolation and economic hardship. Some risk factors vary with age, gender, sexual orientation and ethnic group. Marginalized groups such as minorities, refugees, the unemployed, people in or Suicide rates can be reduced if leaving prisons, depression and anxiety are and those treated. Studies have already with confirmed the beneficial effects mental health of antidepressants and problems, are psychotherapy. particularly at risk.

Suicide and attempted suicide present serious public health problems. In some countries, more people commit suicide than are killed in traffic accidents. Age and gender are important aspects of suicide risk and trends and need to be considered in the development of suicide prevention programmes. Media reporting that glamorizes suicide adversely influences public attitudes and may contribute to an increase in suicidal behaviour. The main recommendations were:

Protective factors

However, the presence of sufficiently strong protective factors may reduce the risk of suicide.

The prevention of suicide and attempted suicide requires a public health approach. The burden of suicide is so large that this should be a responsibility for the entire government, under the leadership of the Ministry of Health. Suicide prevention programmes are needed. They should consider specific interventions for different groups at risk (e.g. age- and gender-

EUR/04/5047810/B7 page 3

related), including tasks allocated to different sectors (education, labour market, social affairs, etc.), and they should be evaluated.

Health care professionals, especially in emergency services, should be trained to identify suicide risk and proactively collaborate with mental health services. Education of both health professionals and the general public should start as early as possible and focus on both risk and protective factors. Policy-oriented research and evaluation of suicide prevention programmes are needed. The media should be involved and trained in suicide prevention and the WHO code of conduct on media behaviour in relation to suicidality should be promoted (7). The Action Plan for adoption at the WHO European Ministerial Conference on Mental Health (Helsinki, January 2005) proposes a number of specific measures, including:

promoting research on suicide prevention and encouraging collection of data on the causes of suicide, by avoiding duplication of statistical records.

Some examples of suicide prevention

The National Strategy for Suicide Prevention in Finland (1986-1996) (8) was implemented throughout the country, with arrangements for local, regional and national implementation. It was systematically evaluated, both internally and externally, and can be considered a success (9). The strategy included public education, improved access to mental health services, crisis intervention, reduction of access to means of suicide, training of health professionals, training in awareness of co-morbidity factors, monitoring of attempted suicide and recording of individuals at risk requiring preventive intervention. The programme incorporated action by professionals, the social services and statutory agencies, but not specifically by people bereaved by suicide. Some other examples of ongoing national programmes are given below. Choose Life the national strategy and action plan to prevent suicide in Scotland (2002) aims to reduce the rate of suicide by 20% by 2013. A national network has been formed with representatives of local councils, police, ambulance, accident and emergency services, prison services and key nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), and a national training and capacity-building programme was established. Implementation is concentrated on 32 local council areas, and the local plans focus on three key objectives:

measuring base rates of stress indicators and identifying groups at risk; targeting marginalized groups with education, information and support programmes; and establishing self-help groups, phone help lines and websites for people in crisis situations.

Strategies for suicide prevention

Suicide prevention strategies are concerned with:

identifying and reducing availability and access to the means of suicide (handguns, toxic substances, etc); improving health care services and promoting supportive and rehabilitation functions for persons affected by suicidal behaviour; improving diagnostic procedures and subsequent treatment; increasing awareness among health care staff of their own attitudes and taboos towards suicide prevention and mental illness; increasing knowledge through public education about mental illness and its recognition at an early stage; supporting media reporting on suicide and attempted suicide;

achieve coordinated action for suicide prevention across health care services, social care services, education, housing, police, welfare and employment services; develop multi-professional training programmes to build capacity for supporting the prevention of suicide; provide financial support for local community and neighbourhood interventions (10).

EUR/04/5047810/B7 page 4

The Action Plan for Preventing Suicidal Behaviour in Estonia is structured on a detailed matrix setting out different strategies for specific target groups and detailing goals, programmes, timing, categories of people responsible, expected results, risks, etc. The plan envisages setting up a national centre with an official mandate and funds for coordinating and developing suicide prevention work in the country. Monitoring of attempted suicide events and recording of individuals at risk who require preventive interventions are included as key elements in the plan. The German National Suicide Prevention Programme (Nationales Suizidprventionsprogramm fr Deutschand) (2003) (11) is remarkable in terms of the broad set of working groups, administrative agencies and federal institutions covered. The following interventions are indicated: public education, crisis intervention, suicide prevention in children and young people, suicide prevention in workplaces, reduction of access to the means of suicide, detection and treatment of depression and related conditions and dealing with specific psychiatric disorders, training of health professionals and awareness training on comorbidity factors. Specific working groups are dedicated to substance abuse disorders and populations at risk, as well as to survivors and bereaved family members. Working with the media is also a key issue covered by the programme. To prevent suicide among adolescents, Denmark has developed an educational programme that has initiated pilot projects in schools and other educational institutions. Teachers, youth workers, clergy, doctors, nurses, social workers, etc. are involved. Driving licence for a teenager is a programme aimed at giving parents basic information about dialogue and frustration and teaching them how to bond with their children (12).

powerful religious and legal sanctions. Ideas about suicide being noble or detestable, brave or cowardly, rational or irrational, a cry for help or a turning away from support contribute not only to confusion but also to ambivalence towards suicide prevention. In many countries, it was not until as late as the 20th century that religious sanctions were removed and suicidal acts ceased to be criminal. Suicide is often perceived as being predestined and even impossible to prevent. Such taboos and emotions are important factors hindering the implementation of suicide prevention programmes. When working in suicide prevention, one must be aware that not only is it necessary to increase knowledge in a rational way, one must also work with unconscious ideas and attitudes about suicide prevention. This kind of work is of great importance in paving the way for the development of suicide prevention programmes in which scientific, clinical and practical knowledge concerning suicide prevention can be conveyed.

Stakeholder involvement

Examples of stakeholder involvement can be found throughout the European Region. The International Association for Suicide Prevention (IASP) is an NGO in official relationship with WHO, bringing together professionals and volunteers from more than fifty different countries and dedicated to preventing suicidal behaviour, alleviating its effects, and providing a forum for academics, mental health professionals, crisis workers, volunteers and suicide survivors. Other organizations play a crucial role in proposing free services to help people who feel suicidal, by telephone, in face-to-face meetings, by letter and by email in a non-judgemental and confidential way. One of the oldest organizations in Europe, the Samaritans has developed a network of international support services, run by volunteers trained in the art of listening and empathy to offer confidential emotional support to any person who is suicidal or despairing. Various suicide prevention centres have been set up across Europe, providing early support and intervention: telephone crisis lines, training for front-line workers and general practitioners,

Challenging the stigma

Suicide has long been a taboo subject and is still surrounded by feelings of shame, fear, guilt and uneasiness. Many people have difficulties discussing suicidal behaviour, which is not surprising since it is associated with extremely

EUR/04/5047810/B7 page 5

support for survivors (friends and family who experience the death of someone by suicide), undertaking research and campaigning for raising public awareness to suicide. Verder (Further On) is a network that supports suicide survivors in Flanders (Belgium), made up of fifteen support groups throughout the Flemish region that initiate and coordinate activities for suicide survivors to help them resolve their grief and pain. The network published a booklet (13) containing basic information on suicide bereavement and how to support survivors. This is freely distributed among general practitioners, hospitals, mental health centres, help lines, selfhelp groups, victim care centres and social services, and is announced in the media for the general public. Other initiatives are a theatre play on survivorship that is presented across the country and a media award for journalists for responsible and respectful portrayal of suicide and suicide survivors. The network launched The Charter of the Rights of Suicide Survivors, which has been endorsed and translated by other organizations in Europe. The survivor has the right:

raise the profile of suicide prevention programmes at the policy-making level. It helps its member organizations, especially in central and eastern European countries, to take action and set up projects with national and local agencies, European academic and research groups, mental health service users and social organizations.

References1

1. Bertolote JM, Fleischmann, S. Suicide and psychiatric diagnosis: a worldwide perspective. World Psychiatry, 2002, 1 (3): 181186. The world health report 2004. Changing history. Geneva, World Health Organization, 2004. Murray CJL, Lopez AD, eds. The global burden of disease: a comprehensive assessment of mortality and disability from diseases, injuries and risk factors in 1990 and projected to 2020. Cambridge, MA, Harvard School of Public Health on behalf of the World Health Organization and the World Bank, 1996. European Health for All database mortality indicators (HFA-MDB) [online database]. Copenhagen, WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2004 (http://www.euro.who.int/InformationSources /Data/20011017_1). Guo B, Harstall C. For which strategies of suicide prevention is there evidence of effectiveness? Copenhagen, WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2004 (Health Evidence Network synthesis report) (http://www.euro.who.int/document/E83583.p df). Suicide prevention in Europe. The WHO European monitoring survey on national suicide prevention programmes and strategies. Copenhagen, WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2002.

2.

3.

to know the truth about the suicide;

4.

to live, wholly, with joy and sorrow, free of stigma or judgment; to find support from relatives, friends, professionals and to place his/her experience in the service of the others; to never be as before: there is a life before the suicide, and a life afterwards.

5.

In Ukraine, a country with one of the highest male suicide rates (61.8 per 100 000) (14), the NGO Human Ecological Health (Odessa) works particularly with prison services and the Ukrainian army, offering training on suicide prevention for officers and medical doctors working in penitentiaries. In Serbia and Montenegro, the association Srce (Heart) has been working for more than ten years in the region of Novi Sad, offering emotional support by telephone for people in crisis and organizing outreach programmes aimed at highschool adolescents. Mental Health Europe, a European NGO, lobbies to heighten awareness of the burden of suicide and

6.

EUR/04/5047810/B7 page 6

7.

From the margins to the mainstream: putting public health in the spotlight: a resource for health communicators. Copenhagen, WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2003 (http://www.euro.who.int/document/e82092_6 .pdf) Suicide can be prevented: Fundamentals of a target and action strategy. Helsinki, National Research and Development Centre for Welfare and Health (STAKES), 1993. Upanne M, Hakanen J, Rautava M. Can suicide be prevented? The Suicide Project in Finland 1992-1995: Goals, implementation and evaluation. Helsinki, National Research and Development Centre for Welfare and Health (STAKES), 1999 (http://www.stakes.fi/verkkojulk/pdf/mu161.p lk/pdf/mu161.p df)

13. WegWijzer voor Nabestaanden na Zelfdoding [Roadmap for suicide survivors]. Halle (Belgium), Werkgroep Verder, 2004 (http://users.pandora.be/nazelfdoding.gent/We gWijzer2004.pdf). 14. Krug EG et al. eds. World report on violence and health. Geneva, World Health Organization, 2002.

8.

9.

Further reading1

International Association for Suicide Prevention http://www.med.uio.no/iasp/index.html Samaritans http://www.samaritans.org.uk/ Verder http://www.werkgroepverder.be/ Srce http://www.centarsrce.org.yu/ Mental Health Europe http://www.mhe-sme.org/

1

10. Choose Life. A national action plan and strategy to prevent suicide in Scotland. Edinburgh, Scottish Executive, 2002 (http://www.scotland.gov.uk/library5/health/clss. pdf) 11. Nationales Suizidprventionsprogramm fr Deutschland. Deutsche Gesellschaft fr Suizidprvention, 2004 (http://suizidpraevention-deutschland.de/) 12. For further information, contact: Centre for Suicide Research Sndergade 17 5000 Odense C Denmark (Tel. +45 66 13 88 11)

All web sites accessed 28 October 2004

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the help received with the preparation of this briefing from Dr Leen Meulenbergs, Ministry of Health, Belgium, Dr Jos Manoel Bertolote, WHO headquarters and Ms Roxana Radulescu, Mental Health Europe. This briefing was produced for the WHO European Ministerial Conference on Mental Health, Helsinki, 1215 January 2005.

Helsinki Conference Secretariat WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION REGIONAL OFFICE FOR EUROPE

Scherfigsvej 8, DK-2100 Copenhagen , Denmark Phone: +45 39 17 14 44/14 73 Fax: +45 39 17 18 78 e-mail: mentalhealth2005@euro.who.int

You might also like

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Mukhyamantri Yuva Swavalamban Yojana ApplicationDocument1 pageMukhyamantri Yuva Swavalamban Yojana ApplicationAbhay tiwariNo ratings yet

- Eastwoods: College of Science and Technology, IncDocument2 pagesEastwoods: College of Science and Technology, IncMichael AustriaNo ratings yet

- MH 2018Document24 pagesMH 2018Shilps PNo ratings yet

- Grade 1 To 12 Daily Lesson Log: Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday FridayDocument5 pagesGrade 1 To 12 Daily Lesson Log: Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday FridayJohn Harries RillonNo ratings yet

- Early Life of Rizal (With Memorias)Document39 pagesEarly Life of Rizal (With Memorias)Mikaehla Suzara0% (1)

- Job Advertisment 31082022638290828893059775Document2 pagesJob Advertisment 31082022638290828893059775ZAIN SAJJAD AWANNo ratings yet

- Ebook PDF Child and Adolescent Development For Educators PDFDocument41 pagesEbook PDF Child and Adolescent Development For Educators PDFdiana.dobson700100% (35)

- 1987 Philippine ConstitutionDocument3 pages1987 Philippine ConstitutionJoya Sugue AlforqueNo ratings yet

- Techstart II Registration ListDocument6 pagesTechstart II Registration ListVibhor ChaurasiaNo ratings yet

- Division Memo For The Orientation of Test Constructors 2021Document9 pagesDivision Memo For The Orientation of Test Constructors 2021maynard baluyutNo ratings yet

- Communication For Academic Purposes - 1912988543Document29 pagesCommunication For Academic Purposes - 1912988543Cresia Mae Sobrepeña Hernandez80% (5)

- Home 168 Manila OJT Partnership ProposalDocument18 pagesHome 168 Manila OJT Partnership Proposal168 HomeNo ratings yet

- Capr-Iii 6282Document52 pagesCapr-Iii 6282yashrajdhamaleNo ratings yet

- CHMSC Educational Technology Course SyllabusDocument20 pagesCHMSC Educational Technology Course SyllabusMichael FigueroaNo ratings yet

- Mules School PLC ProfileDocument2 pagesMules School PLC Profileapi-288801653No ratings yet

- Advantages of ProbabilityDocument3 pagesAdvantages of Probabilityravindran85No ratings yet

- Action Plan On Reading Intervention ForDocument4 pagesAction Plan On Reading Intervention ForKATHLYN JOYCENo ratings yet

- Detailed Lesson Plan Teaches World History ObjectivesDocument4 pagesDetailed Lesson Plan Teaches World History ObjectivesDan Lhery Susano Gregorious84% (82)

- San Rafael, Zaragoza, Nueva Ecija Junior High SchoolDocument55 pagesSan Rafael, Zaragoza, Nueva Ecija Junior High SchoolNica Mae SiblagNo ratings yet

- ProspectusDocument48 pagesProspectusazhar aliNo ratings yet

- For DemoDocument23 pagesFor DemoShineey AllicereNo ratings yet

- Traditional AssessmentDocument11 pagesTraditional AssessmentGUTLAY, Sheryel M.No ratings yet

- Learning For Change: Presentation by Raksha RDocument15 pagesLearning For Change: Presentation by Raksha RRaksha RNo ratings yet

- Gyanranjan Nath SharmaDocument7 pagesGyanranjan Nath SharmaGyanranjan nath SharmaNo ratings yet

- Problems With SubjunctivesDocument21 pagesProblems With SubjunctivesMeridian Sari DianitaNo ratings yet

- Daily Newspaper - 2015 - 11 - 08 - 000000Document54 pagesDaily Newspaper - 2015 - 11 - 08 - 000000Anonymous QRT4uuQNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan KonstruktivismeDocument9 pagesLesson Plan KonstruktivismeAzlan AhmadNo ratings yet

- Ipcrf - Designation Letter VTPDocument4 pagesIpcrf - Designation Letter VTPCatherine MendozaNo ratings yet

- ICTv3 Implementation GuideDocument98 pagesICTv3 Implementation Guiderhendrax2398No ratings yet

- C.Ganapathy Sxcce Template - For - PHD - Holders - Profile PDFDocument14 pagesC.Ganapathy Sxcce Template - For - PHD - Holders - Profile PDFVisu ViswanathNo ratings yet