Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Outline - Self Monitoring Agents

Uploaded by

Aditya SarkarOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Outline - Self Monitoring Agents

Uploaded by

Aditya SarkarCopyright:

Available Formats

Draft

Self Monitoring Agents

This note looks at some of the broad issues that arise when we evaluate the role of self-monitoring agents in international development.

Who are Self Monitoring Agents (SMAs)? There does not appear to be a consensus in academic writing as to the exact definition of the phrase self monitoring agent. Broadly, SMAs seem to refer to (i) the organisations which assess their own effectiveness against the broad goals set by a funding body (such as the Clinton Global Initiative, for example) or a specialised organisation that looks to measure the effectiveness of various actors in the field of developmental (primarily NGOs).

2

2.1 2.2

Why are SMAs relevant? At a theoretical level, SMAs seem to occupy an important role in the assessment of developmental projects, and organisations. With increased emphasis on the importance of participation in development, there has been a growing recognition that the monitoring and evaluation of development and other community-based initiatives should be participatory. Along with this, there has been a greater interest (and concern) in monitoring and evaluation by donors, governments, NGOs and others. This is referred to in some academic literature as participatory monitoring and evaluation (PME). This participatory form of development is driven by several factors a move towards performance based accountability and management by results, an increasingly challenging financial environment (specially in the last few years), a demand for demonstrated achievement, greater decentralisation which in turn requires new methods of oversight, and the growing capacity of NGOs and community bases organisations as actors in the field of development. PME has been part of the policy making domain of larger donor organisations since the 1980s. In short, development organisations need to know how effective their efforts have been. But who should make these judgements, and on what basis? Varying approaches can be taken, which involve local people, development agencies, and policy makers deciding together how progress should be measured, and results acted upon. What is PME and why is it important? There appears to a great deal of divergence between the ways in which organisations, field practitioners, academic researchers, etc. understand the meaning and practice of PME. However, broadly speaking, it refers to the processes by which an organisation measures its results (or is measured, by an impartial specialist body) against an independent benchmark established by another organisation (for the same sector).

2.3

2.4

Uses of PME PME is usually understood as performing the following functions:

(i) (ii) (iii)

impact assessment, project management and planning, organisational strengthening or institutional learning,

Draft

(iv) (v)

understanding stakeholder perspectives, and public accountability. The Top-down or Conventional Approach The conventional approach to monitoring an organisations performance within the heads set out in paragraph 4 above has focussed on a quantitative measurement which strives for objectivity, and is orientated towards the needs of programme funders to make judgments about the efficacy of such an organisation. This can safely be called the Topdown Approach to PME. This approach is geared towards enhancing cost efficiency and accountability, and is usually conducted by outsiders with a view to providing an objective evaluation. This approach is frequently criticised as being costly and ineffective, because it fails to actively involve project beneficiaries, making project evaluation an increasingly specialised field and activity removed from the on-going planning and implementation of development initiatives. Focussing on quantitative information, also ignores a fuller assessment of project outcomes, processes and changes. I would argue that many of the organisations such as Givewell (http://www.givewell.org/) and Philanthropy Capital (http://www.philanthropycapital.org) adopt a top down approach to monitoring an organisations approach. Givewell as an example of top down evaluation

5.4.1

5

5.1

5.2

5.3

5.4

In its 2011 international aid process review , Givewell states: Our focus is on finding outstanding charities rather than completing an in-depth investigation for each organization we consider. For that reason, we rely on heuristics, or meaningful shortcuts, to distinguish between organizations and identify ones that we think will ultimately qualify for our recommendations. In general, we believe that charities should bear the burden of proof when soliciting donations from "casual" donors - donors that do not have the time or resources to conduct significant in-depth investigations of charities on their own. We therefore only recommend charities that can make a strong case that they are significantly improving lives in a cost-effective way and can use additional donations to expand their proven program(s) (see our criteria). Charities that we do not recommend may be effective, but we have not identified a strong case for a casual donor to be confident in such charities

5.4.2

Some of the meaningful shortcuts that it has evolved are: (i) High-quality monitoring and evaluation reports published on the charitys website. This measures the impact that a charity has had, for example, for an education based charity such as Camfed impact would be measured by, 2 inter alia, attendance rates and test scores ; A focus on priority programmes as identified by Givewell. These are 3 predominantly related to disease prevention and/or malnutrition.

(ii)

1 2 3

Available at http://www.givewell.org/international/process/2011. For a full list of criteria, please see http://givewell.org/international/technical/criteria/impact. A full list of priority programs is available at http://www.givewell.org/international/program-reviews#Priorityprograms.

Draft

(iii) (iv) (v)

Creation of an outsized impact; Extreme cost effectiveness; and Promising causes]

5.5

New Philanthropy Capital (NPC), follows a similar approach, publishing a little blue book which is intended to act as a guide to analysing charities, for both charities and funders. NPC is impact driven to the extent that it even publishes a document called Principles of Good Impact Reporting. The various documents produced by NPC are attached to the email accompanying this note. The Bottom-up Approach In response to the problems identified with conventional approaches to project monitoring and evaluation, the emphasis has shifted towards the recognition of locally relevant processes of gathering data, and more specifically towards self-monitoring by the organisations themselves. The main arguments for this approach are: enhanced participation of beneficiaries, increased authenticity of findings and improved sustainability of project activities, and more efficient allocation of resources. The World Bank has said, for example, in a project evaluation report on a poverty reduction project in Andhra Pradesh: Given the limited budgets allocated to supervision activities, supervising World Bank projects has long been a serious challenge particularly in sprawling rural areas with small poor communities spread out over vast distances. Innovative ways of sharing monitoring and supervision roles and responsibilities with local partners, therefore, carry important practical implications for project managers, whose own capacity to monitor developments and identify challenges is limited by distance and time constraints. How do SMAs fit into this? Donor identification: There is, of course a distinction between governmental or international donors and smaller donors. However, many of the independent organisations examining the impact of charities and developmental organisations appear to be targeting the latter. Charities/Developmental Organisations being assessed: The organisations being assessed attempt to comply with the guidelines established by the assessing organisation.

7.2.1

6

6.1

(i) (ii) (iii)

6.2

7

7.1

7.2

Camfed is an excellent example of this. On its website it publishes an impact overview broken down into geographical regions and setting out the number of scholarships given, number of students supported, number of small businesses that grew out of the CAMA network, etc. Camfeds interaction with the Clinton Global Initiative (CGI) is also interesting. CGI requires that each member makes a Commitment to Action. A Commitment to Action is a concrete plan to address a global challenge. Commitments can be small or large, global or local. A multinational corporation might pledge to reduce its packaging saving money while reducing waste. A nonprofit might seek to expand an effective program into new geographies. No matter their size or scope, commitments help CGI members translate practical goals into meaningful and

7.2.2

Draft

measurable results. CGI works with each member to develop an achievable plan, and members report back on the progress they make over time.

7.2.3

Each such Commitment needs to be new, specific and measurable, either qualitatively or quantitatively. Camfeds commitment states that over the next five years, CAMFED commits to providing at least 800,000 additional years of education to girls and vulnerable boys from extremely poor families in rural areas of seven sub-Saharan African countries; develop local capacity to increase accountability in educational delivery in 4,000 communities, expand government partnerships to deliver best practice in girls' education in 10 countries; support the creation of 5,500 new businesses by providing grants or micro-loans to young women entrepreneurs and training in business and leadership skills; and measure 4 the long-term effects of girls' education through 10 research partnerships. These are specific quantitative goals that Camfed can show that it has achieved, and to a large extent, an articulation by the charity of what it hopes to achieve in a specific timeframe.

7.2.4

8

8.1

The provocative counterpoint The primary conflict in the way that self monitoring agents and charity/developmental organisation monitoring agencies operate follows from the overarching theme of the seminar. Is there a way of ensuring that there is greater stakeholder feedback in the process of charity evaluation? To what extent can stakeholders, or the community which is the recipient of aid able to articulate their/its interests in the targets that a developmental organisation needs to achieve to satisfy its donors? As things stand monitoring organisations formulate their own standards (albeit with feedback) but the charities themselves have to fit into established objective boxes to demonstrate that they are effective.

Available at http://www.clintonglobalinitiative.org/commitments/commitments_search.asp?id=265639.

You might also like

- LG LFX31945 Refrigerator Service Manual MFL62188076 - Signature2 Brand DID PDFDocument95 pagesLG LFX31945 Refrigerator Service Manual MFL62188076 - Signature2 Brand DID PDFplasmapete71% (7)

- Stakeholder EngagementDocument9 pagesStakeholder Engagementfaisal042006100% (1)

- BPS C1: Compact All-Rounder in Banknote ProcessingDocument2 pagesBPS C1: Compact All-Rounder in Banknote ProcessingMalik of ChakwalNo ratings yet

- Bring Your Gear 2010: Safely, Easily and in StyleDocument76 pagesBring Your Gear 2010: Safely, Easily and in StyleAkoumpakoula TampaoulatoumpaNo ratings yet

- Impact MeasurementDocument14 pagesImpact MeasurementRos FlannelaNo ratings yet

- The Means by Which Poor People Convert Small Sums of Money Into Large Lump Sums (Rutherford 1999)Document7 pagesThe Means by Which Poor People Convert Small Sums of Money Into Large Lump Sums (Rutherford 1999)Ramachandra ReddyNo ratings yet

- Stakeholder Feedback GuideDocument48 pagesStakeholder Feedback GuideYudit PuspitariniNo ratings yet

- Measure What You Treasure EPEWG February 08Document3 pagesMeasure What You Treasure EPEWG February 08InterActionNo ratings yet

- CGD Policy Paper 52 Perakis Savedoff Does Results Based Aid Change AnythingDocument61 pagesCGD Policy Paper 52 Perakis Savedoff Does Results Based Aid Change AnythingWauters BenedictNo ratings yet

- Executive SummaryDocument12 pagesExecutive SummaryZubin PurohitNo ratings yet

- Coffee With Ngos A Forum For Brewing IdeasDocument7 pagesCoffee With Ngos A Forum For Brewing IdeascazdylupeNo ratings yet

- Impact AnalysisDocument39 pagesImpact AnalysisAndrea Amor AustriaNo ratings yet

- Community Development StrategyDocument12 pagesCommunity Development StrategyJoyceCulturaNo ratings yet

- IOD PARC Final Evaluation DFID CSCF Lessons - Communications PieceDocument7 pagesIOD PARC Final Evaluation DFID CSCF Lessons - Communications PieceLauraNo ratings yet

- CSBDF - Moving-the-Needle-Report - 2-2-23 MilesJames - EditsDocument23 pagesCSBDF - Moving-the-Needle-Report - 2-2-23 MilesJames - EditsAdam SaferNo ratings yet

- SLP Activity TUDLAS GRICHENDocument7 pagesSLP Activity TUDLAS GRICHENGrichen TudlasNo ratings yet

- SIB SFFedReserveDocument6 pagesSIB SFFedReservear15t0tleNo ratings yet

- 56 Eval and Impact AssessmentDocument37 pages56 Eval and Impact AssessmentSamoon Khan AhmadzaiNo ratings yet

- Interaction Consultation BenchmarksDocument5 pagesInteraction Consultation BenchmarksInterActionNo ratings yet

- World Vision International 2017 Report - Panel FeedbackDocument7 pagesWorld Vision International 2017 Report - Panel Feedbackwadih fadllNo ratings yet

- Ricardo Millett, Former Director of Evaluation, W.K. Kellogg FoundationDocument12 pagesRicardo Millett, Former Director of Evaluation, W.K. Kellogg FoundationKomal GoklaniNo ratings yet

- Jc579-Strategies Ngo en PDFDocument25 pagesJc579-Strategies Ngo en PDFGautamNo ratings yet

- DP Delivering Sustainable Development Public Private 100415 enDocument8 pagesDP Delivering Sustainable Development Public Private 100415 enHossein DavaniNo ratings yet

- Delivering Sustainable Development: A Principled Approach To Public-Private FinanceDocument8 pagesDelivering Sustainable Development: A Principled Approach To Public-Private FinanceOxfamNo ratings yet

- Draft 13 April 2012: Table 1. Outcomes Map For The UNIID-SEA ProjectDocument10 pagesDraft 13 April 2012: Table 1. Outcomes Map For The UNIID-SEA ProjectSegundo E RomeroNo ratings yet

- PME ToolDocument12 pagesPME ToolAmare ShiferawNo ratings yet

- 1109 Integrated Reporting ViewDocument12 pages1109 Integrated Reporting ViewbarbieNo ratings yet

- Theoretical FrameworkDocument6 pagesTheoretical FrameworkHatake KakashiNo ratings yet

- CGAP Technical Guide Appraisal Guide For Microfinance Institutions Mar 2008Document86 pagesCGAP Technical Guide Appraisal Guide For Microfinance Institutions Mar 2008leekosalNo ratings yet

- SawhnyKEPRRA AwardDocument43 pagesSawhnyKEPRRA AwardalisaamNo ratings yet

- Rethinking Capacity DevelopmentDocument2 pagesRethinking Capacity Developmentjoaquin navasNo ratings yet

- Improving PerformancDocument6 pagesImproving PerformancImprovingSupportNo ratings yet

- Inclusive Business Ex-Ante Impact Assessment: A Tool For Reporting On ADB's Contribution To Poverty Reduction and Social InclusivenessDocument34 pagesInclusive Business Ex-Ante Impact Assessment: A Tool For Reporting On ADB's Contribution To Poverty Reduction and Social InclusivenessADB Poverty ReductionNo ratings yet

- Stakeholder Management: Critical to Project Success: A Guide for Effective Project ManagersFrom EverandStakeholder Management: Critical to Project Success: A Guide for Effective Project ManagersNo ratings yet

- 1 - Results-Based Management - Friend or Foe PDFDocument8 pages1 - Results-Based Management - Friend or Foe PDFZain NabiNo ratings yet

- Global Alliance For Banking On Values: Financial Capital Expansion and Impact Measurement of Values Based BankingDocument4 pagesGlobal Alliance For Banking On Values: Financial Capital Expansion and Impact Measurement of Values Based BankingKumaramtNo ratings yet

- CDFIs Stepping Into The Breach - An Impact Evaluation - Summary RepoDocument58 pagesCDFIs Stepping Into The Breach - An Impact Evaluation - Summary RepoAdam SaferNo ratings yet

- Corporate Social Responsibility and Crowdfunding: The Experience of The Colectual Platform in Empowering Economic and Sustainable ProjectsDocument20 pagesCorporate Social Responsibility and Crowdfunding: The Experience of The Colectual Platform in Empowering Economic and Sustainable Projectssita deliyana FirmialyNo ratings yet

- Ass-2 Proposal MBAS-906Document9 pagesAss-2 Proposal MBAS-906tsendsurenNo ratings yet

- InterAction - Effective Capacity Building in USAID Forward - Oct 2012Document8 pagesInterAction - Effective Capacity Building in USAID Forward - Oct 2012InterActionNo ratings yet

- Resource Mobilization and Financial ManagementDocument31 pagesResource Mobilization and Financial ManagementqasimNo ratings yet

- Feasibility StudyDocument7 pagesFeasibility StudyDhaval ParekhNo ratings yet

- Frequently Asked Questions: Pay For Success/Social Impact BondsDocument10 pagesFrequently Asked Questions: Pay For Success/Social Impact Bondsar15t0tleNo ratings yet

- MDG 201 BMDocument105 pagesMDG 201 BMPriya BhatterNo ratings yet

- Monitoring With CART PrinciplesDocument24 pagesMonitoring With CART PrinciplesoscarNo ratings yet

- Managing Global Benefits:: Challenges and OpportunitiesDocument16 pagesManaging Global Benefits:: Challenges and OpportunitiesWinny Shiru MachiraNo ratings yet

- Social Investment GuideDocument68 pagesSocial Investment GuidelorektaNo ratings yet

- The Business Value of Impact Measurement: Giin Issue BriefDocument52 pagesThe Business Value of Impact Measurement: Giin Issue BriefLaxNo ratings yet

- Feedback Mechanisms in International Assistance OrganizationsDocument34 pagesFeedback Mechanisms in International Assistance OrganizationsZineil BlackwoodNo ratings yet

- Ced Li ProposalDocument10 pagesCed Li ProposalSri NandhniNo ratings yet

- Social Ventures: Funding: Navigating The Challenges of Capital RaisingDocument4 pagesSocial Ventures: Funding: Navigating The Challenges of Capital RaisingSudikcha KoiralaNo ratings yet

- Chapter OneDocument7 pagesChapter Onejtemu_1No ratings yet

- The Omidyar NetworkDocument17 pagesThe Omidyar NetworkDaRtHVaDeR2470No ratings yet

- UntitleddocumentDocument2 pagesUntitleddocumentapi-336333840No ratings yet

- Sec13 - 2011 - FABB - Policy Brief - MonitoringEvaluationDocument2 pagesSec13 - 2011 - FABB - Policy Brief - MonitoringEvaluationInterActionNo ratings yet

- Handbook On Stakeholder ConsultaionDocument56 pagesHandbook On Stakeholder ConsultaionAzhar KhanNo ratings yet

- I.1. The Role of Accountability in Promoting Good GovernanceDocument13 pagesI.1. The Role of Accountability in Promoting Good GovernancejpNo ratings yet

- The Corporate Social Responsibility Strategies and Activities Employed by The Equity Bank in Kenya To Improve Its PerformanceDocument5 pagesThe Corporate Social Responsibility Strategies and Activities Employed by The Equity Bank in Kenya To Improve Its PerformanceInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)No ratings yet

- Making A Difference - Confidence and Uncertainty in Demonstrating Impact - June 2008Document1 pageMaking A Difference - Confidence and Uncertainty in Demonstrating Impact - June 2008InterActionNo ratings yet

- Assessment of The DSWD SEA-K StrategyDocument51 pagesAssessment of The DSWD SEA-K StrategyAnonymous dtceNuyIFI100% (1)

- Bba - 6 Sem - Project Appraisal - Lecture 39&40Document5 pagesBba - 6 Sem - Project Appraisal - Lecture 39&40Jordan ThapaNo ratings yet

- Working Paper 9Document34 pagesWorking Paper 9Guillaume GuyNo ratings yet

- Organizational Development PlanningDocument11 pagesOrganizational Development PlanningPaul GelvosaNo ratings yet

- Writing A Good PaperDocument2 pagesWriting A Good PaperAditya SarkarNo ratings yet

- v1 ADS Peace Security HoADocument10 pagesv1 ADS Peace Security HoAAditya SarkarNo ratings yet

- Policy Memorandum On Child Marriages Among Syrian RefugeesDocument7 pagesPolicy Memorandum On Child Marriages Among Syrian RefugeesAditya SarkarNo ratings yet

- r1012 SceatsbreslinDocument89 pagesr1012 SceatsbreslinAditya SarkarNo ratings yet

- Nehru SpeechDocument6 pagesNehru SpeechAditya SarkarNo ratings yet

- Misc 8DNL 8MPL 8MPN B PDFDocument41 pagesMisc 8DNL 8MPL 8MPN B PDFVesica PiscesNo ratings yet

- Principled Instructions Are All You Need For Questioning LLaMA-1/2, GPT-3.5/4Document24 pagesPrincipled Instructions Are All You Need For Questioning LLaMA-1/2, GPT-3.5/4Jeremias GordonNo ratings yet

- Week 3 Lab Arado, Patrick James M.Document2 pagesWeek 3 Lab Arado, Patrick James M.Jeffry AradoNo ratings yet

- Spanish Greeting Card Lesson PlanDocument5 pagesSpanish Greeting Card Lesson Planrobert_gentil4528No ratings yet

- Ultra Electronics Gunfire LocatorDocument10 pagesUltra Electronics Gunfire LocatorPredatorBDU.comNo ratings yet

- Source:: APJMR-Socio-Economic-Impact-of-Business-Establishments - PDF (Lpubatangas - Edu.ph)Document2 pagesSource:: APJMR-Socio-Economic-Impact-of-Business-Establishments - PDF (Lpubatangas - Edu.ph)Ian EncarnacionNo ratings yet

- Community Profile and Baseline DataDocument7 pagesCommunity Profile and Baseline DataEJ RaveloNo ratings yet

- Raiders of SuluDocument1 pageRaiders of SuluBlexx LagrimasNo ratings yet

- 12 Step Worksheet With QuestionsDocument26 pages12 Step Worksheet With QuestionsKristinDaigleNo ratings yet

- Tribes Without RulersDocument25 pagesTribes Without Rulersgulistan.alpaslan8134100% (1)

- Regulasi KampenDocument81 pagesRegulasi KampenIrWaN Dompu100% (2)

- Design ProjectDocument60 pagesDesign Projectmahesh warNo ratings yet

- Atoma Amd Mol&Us CCTK) : 2Nd ErmDocument4 pagesAtoma Amd Mol&Us CCTK) : 2Nd ErmjanviNo ratings yet

- Church and Community Mobilization (CCM)Document15 pagesChurch and Community Mobilization (CCM)FreethinkerTianNo ratings yet

- 11-Rubber & PlasticsDocument48 pages11-Rubber & PlasticsJack NgNo ratings yet

- Stress Management HandoutsDocument3 pagesStress Management HandoutsUsha SharmaNo ratings yet

- Use of The Internet in EducationDocument23 pagesUse of The Internet in EducationAlbert BelirNo ratings yet

- Transportation of CementDocument13 pagesTransportation of CementKaustubh Joshi100% (1)

- School Based Management Contextualized Self Assessment and Validation Tool Region 3Document29 pagesSchool Based Management Contextualized Self Assessment and Validation Tool Region 3Felisa AndamonNo ratings yet

- Anker Soundcore Mini, Super-Portable Bluetooth SpeakerDocument4 pagesAnker Soundcore Mini, Super-Portable Bluetooth SpeakerM.SaadNo ratings yet

- Designed For Severe ServiceDocument28 pagesDesigned For Severe ServiceAnthonyNo ratings yet

- Tomb of Archimedes (Sources)Document3 pagesTomb of Archimedes (Sources)Petro VourisNo ratings yet

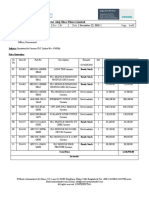

- LC For Akij Biax Films Limited: CO2012102 0 December 22, 2020Document2 pagesLC For Akij Biax Films Limited: CO2012102 0 December 22, 2020Mahadi Hassan ShemulNo ratings yet

- Importance of Porosity - Permeability Relationship in Sandstone Petrophysical PropertiesDocument61 pagesImportance of Porosity - Permeability Relationship in Sandstone Petrophysical PropertiesjrtnNo ratings yet

- Sheet-Metal Forming Processes: Group 9 PresentationDocument90 pagesSheet-Metal Forming Processes: Group 9 PresentationjssrikantamurthyNo ratings yet

- 123Document3 pages123Phoebe AradoNo ratings yet

- IPA Smith Osborne21632Document28 pagesIPA Smith Osborne21632johnrobertbilo.bertilloNo ratings yet