Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Assessment of Concussion from Sideline to Clinic

Uploaded by

CiiFitriOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Assessment of Concussion from Sideline to Clinic

Uploaded by

CiiFitriCopyright:

Available Formats

Assessment of Concussion from the Sideline to

Your Clinic

Eugene Hwang, M.D., M.S.

June 10, 2010

Family Medicine, Emory University

School of Medicine, PGY-3

Sports Medicine, University of Nevada

Las Vegas, PGY-4 Fellow

Ahhhh memories or lack there of

Definition

Mild traumatic brain injury

(mTBI)

Abrupt

acceleration/deceleration of the

brain transient loss of brain

function physical, cognitive,

or emotional signs/symptoms

< 10 % concussions involve

LOC

300,000 concussions/year

3% to 9% of high school and

college football injuries involve

concussions

Pathophysiology

Linear/rotational forces of

acceleration and deceleration on or

within the brain

Microscopic level:

neuron depolarization

ion regulation

membrane channels

axon integrity

glucose metabolism

cell membrane stability

production of oxidative free radicals

Rare to see skull fractures, cerebral

edema, intracranial bleeds, and

epidural/subdural hematomas

Cantu Classification Guidelines, 1986

Grade 1: No loss of consciousness, Post-traumatic

amnesia for fewer than 30 minutes

Grade 2: Loss of consciousness for fewer than 5

minutes OR Post-traumatic amnesia for more

than 30 minutes

Grade 3: Loss of consciousness for more than 5

minutes OR Post-traumatic amnesia for more

than 24 hours

Colorado Medical Society Guidelines,

1991

Grade 1: No loss of consciousness, No post-traumatic

amnesia, Confusion

Grade 2: No loss of consciousness, Post-traumatic

amnesia, Confusion

Grade 3: Loss of consciousness of any duration

American Academy of Neurology

Guidelines, 1997

Grade 1: No loss of consciousness, Concussion

symptoms for fewer than 15 minutes

Grade 2: No loss of consciousness, Concussion

symptoms for more than 15 minutes

Grade 3: Loss of consciousness of any duration

Classification of Concussion

According to the Zurich Conference in 2008:

Concussion grading scales should no longer be used

Terms simple and complex no longer used

Concussion now considered as a single entity that can be

affected by various modifying factors

Definition (Consensus Statement on Concussion in Sport: 3

rd

International Conference on Concussion in Sport, Zurich,

November 2008)

Caused by direct blow to head, face, neck, or elsewhere on the body with an

impulsive force to the head

Results in rapid onset of short-lived neurological impairment that resolves

spontaneously

May result in neuropathological changes, but acute clinical symptoms reflect

functional disturbance rather than structural injury

Results in graded set of symptoms that may or may not involve loss of

consciousness. Resolution of symptoms typically follows sequential course

No abnormality is seen on standard neuroimaging

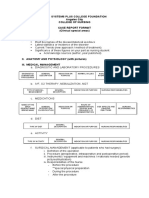

Concussion Assessment

Assessment of acute concussion is multifactorial

Assess signs, symptoms, behavior, and abnormal brain function

Test memory

What team are we playing?

Who scored last?

Test cognitive functioning

Word recall (cat, pen)

Digit recall (say 4-2-5 backwards)

Months in order (recall months in backward order)

Neurological exam is paramount

Speech, eye motion, pupils, pronator drift, balance testing

Presence of one or more of these factors indicate high probability of concussion

and should necessitate removal from field

Sport Concussion Assessment Tool (SCAT)

Quick standardized tool for concussion assessment

Sideline evaluation

(1.) ABCs

(2.) Exclude cervical spine injury

(3.) Evaluate concussion, use

standardized tools (i.e. SCAT) if

available

(4.) Do not leave the player alone

Serial monitoring for initial few hours

following injury to observe for

deterioration

(5.) Player not allowed to return to

field on day of injury

Exception: certain elite adult athletes

ED/Clinic Setting

Do a complete H+P

Do a comprehensive neurological exam

Monitor for worsening signs/symptoms

Obtain additional info from other sources (parents, coaches, trainers,

etc.)

Emergent neuroimaging only if there is concern for severe brain injury

or abnormality

Neuroimaging

CT

Study of choice

Greater accessibility

Good for intracranial hemorrhage, contusion, or herniation

MRI

More sensitive and specific than CT in identifying small cerebral contusions, edema,

and small non-hemorrhagic lesions

Prohibited by: cost, availability, claustrophobia, metal hardware in body

Other imaging studies

Functional MRI (f MRI)

Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI)

Positron Emission Tomography (PET)

Single Photon Emission Computerized Tomography (SPECT)

Near Infrared Spectroscopy (NIRS)

Concussion Management

Patience is key!

Physical AND cognitive rest until symptoms resolve.

When symptomatic, restrict/prohibit physical activity and activities involving

attention and concentration.

Emphasize delay in recovery if athlete resumes these activities too soon.

Do not overlook depression, anxiety, or mood disturbances.

Recovery should be based on the individual, NOT tables or guidelines.

Several factors will modify concussion management (Table 2).

Concussion Modifiers

TABLE 2. Concussion Modifiers

Factors: Modifier:

Symptoms Number

Duration (>10 days)

Severity

Signs Prolonged LOC (>1 min), amnesia

Sequelae Concussive convulsions

Temporal Frequency - repeated concussions over time

Timing - injuries close together in time

Recency - recent concussion or TBI

Threshold Repeated concussions occurring with

progressively less impact force or slower

recovery after each successive concussion

Concussion Modifiers (Table 2,

Continued)

Factors: Modifier:

Threshold Repeated concussions occurring with

progressively less impact force or slower

recovery after each successive concussion

Age Child and adolescent (< 18 years old)

Co- and Pre-morbidities Migraine, depression or other mental health

disorders, attention deficit hyperactivity

disorder (ADHD), learning disabilities (LD),

sleep disorders

Medication Psychoactive drugs, anticoagulants

Behaviour Dangerous style of play

Sport High-risk activity, contact and collision sport,

high sporting level

Cantu Concussion Guidelines, Return

to Play

Management based on first concussion:

Grade 1: Athlete may return to play if asymptomatic for one week

(if athlete is totally asymptomatic, return to play on

same day may be considered).

Grade 2: Athlete may return to play if asymptomatic for one

week.

Grade 3: Athlete may not return to play for at least one month;

athlete may then return to play if asymptomatic for one

week.

Colorado Medical Society Guidelines,

Return to Play

Management based on first concussion:

Grade 1: Athlete may return to play if asymptomatic for 20

minutes.

Grade 2: Athlete may return to play if asymptomatic for one

week.

Grade 3: Athlete should be transported to a hospital

emergency department; athlete may return to play

one month after injury if asymptomatic for two

weeks.

American Academy of Neurology

Guidelines, Return to Play

Management based on first concussion:

Grade 1: Athlete may return to play if asymptomatic for 15

minutes.

Grade 2: Athlete may return to play if asymptomatic for one

week.

Grade 3: Athlete should be transported to a hospital emergency

department; if athlete had brief loss of consciousness

(i.e., seconds), may return to play when asymptomatic for

one week; if athlete had prolonged loss of consciousness

(i.e., minutes), may return to play when asymptomatic for

two weeks.

Graduated Return to Play Protocol

Step-wise process

Each step = 24 hours

Progress to next step if

asymptomatic for at least 24

hours at that current level

If symptomatic, rest for 24

hours, then drop athlete down

to previous asymptomatic step

and try to progress again

Graduated Return to Play Protocol

TABLE 1. Graduated Return to Play Protocol

Rehabilitation Stage Functional Exercise at Each Stage of Rehabilitation Objective of Each Stage

1. No activity Complete physical and cognitive rest Recovery

2. Light aerobic exercise Walking, swimming or stationary cycling keeping Increase HR

intensity, <70% MPHR; no resistance training

3. Sport-specific exercise Skating drills in ice hockey, running drills in soccer; Add movement

no head impact activities

4. Non-contact training drills Progression to more complex training drills, eg, Exercise, coordination, and

cognitive passing drills in football and ice hockey; may load

start progressive resistance training

5. Full contact practice Following medical clearance, participate in normal Restore confidence and assess

training activities functional skills by coaching staff

6. Return to play Normal game play

Pharmacology

Helps to manage symptoms including anxiety, depression, insomnia, and

headache

Acute anxiety BZDs

Depression SSRIs

Insomnia BZDs, TCAs

Cognitive slowing/Fatigue psychostimulants (i.e. Provigil), dopaminergic agents

(i.e. Levodopa)

Mania/Psychosis typical/atypical antipsychotics (i.e. Risperdal)

Prior to returning to play, athlete needs to be symptom-free and off these

medications (except for antidepressants)

Initiation of these medications need close monitoring

Neuropsychological Testing

Provides a way to assess information relating to neurological deficits suffered

post-concussion when compared to baseline neurological function

Adjunct to clinical decision making process

Expense ($750-$4,000) and time factor (30 min to 3 hours) limits widespread

use

Trained neuropsychologists are needed to assess findings

Examples:

Immediate Post Concussion Assessment and Cognitive Testing

(ImPACT)

Balance Error Scoring System (BESS)

Automated Neuropsychological Assessment Metrics (ANAM)

Genetics

Current investigations ongoing to evaluate the association of

genotypes, alleles, and genetic biomarkers to concussions

S100B

predicts long-term disability from a head injury

Apo E4

risk factor for Alzheimers

G-219T polymorphism of ApoE promoter

increased risk for Alzheimers and unfavorable post-concussive

outcomes

Tau mutation on Chromosome 17

frontotemporal dementia

Pediatric Athlete

Not a little adult!

Growth and development make

concussion assessment and

management very difficult

Less neck and shoulder

musculature less capable of

transferring kinetic energy at the

head throughout the body

Neurological development at risk

Ability to focus

Sustain attention

Memory recall

Rapid information processing

Pediatric Athlete

No set timetable for recovery

Need to be conservative on return to play protocol

Consider extending out time of one or more steps

Emphasize cognitive rest and longer recovery period

Studies still limited in terms of the pediatric population

Repeated Concussive Injury

http://espn.go.com/video/clip?categoryid=3060647&id=5163151

Repeated Concussive Injury

Concern for Second Impact Syndrome (SIS)

Athlete sustains head injury while still symptomatic from a previous head

injury

Second head injury leads to metabolic disruption and loss of autoregulation

of cerebral blood supply

Results in cerebral vascular engorgement, cerebral edema/swelling,

increased intracranial pressure, cerebral/brainstem herniation, and

ultimately, coma and death

Rare, but is of great concern in pediatric population due to immaturity

of the brain

Contact sports (i.e. football, hockey) increase risk of SIS

Ongoing research

Pediatric population

Genetic/biomarker testing

Second Impact Syndrome

Male vs. female athlete

Protective equipment (i.e.

helmets, mouthgards)

Take Home Points

In terms of concussions, treat each athlete or patient as an individual

Be thorough in the initial evaluation and subsequent follow-up

Neuroimaging valid when suspicious for serious brain injury, otherwise

no imaging needed

Be conservative on return to play

Be even more conservative with pediatric athletes

The End

References

1. McCrory, P. and Meeuwisse, W. Consensus Statement on Concussion in Sport: the 3rd International Conference on

Concussion in Sport held in Zurich, November 2008. Br. J. Sports Med. 2009 (Suppl I): 43; i76-i84.

2. McCrory, P. and Johnston, K. Summary and Agreement Statement of the 2nd International Conference on Concussion in

Sport, Prague 2004. Clin. J. Sports Med: Vol 15, Number 2, March 2005, pp 48-55.

3. Aubry, M. and Cantu, R. Summary and Agreement Statement of the First International Conference in Sport, Vienna 2001.

The Physician and Sports Medicine: Vol 30, Number 3, February 2002.

4. Herring, S. and Bergfield, J. Concussion (Mild Traumatic Brain Injury) and the Team Physician: A Consensus Statement.

Official Journal of the American College of Sports Medicine, Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise: November 2005,

pp 2012-2016.

5. Anderson, T. and Heitger, M. Concussion and Mild Head Injury. Practical Neurology 2006: Vol 6, pp 342-357.

6. Akhavan, A. and Flores, C. How should we follow athletes after a concussion?. The Journal of Family Practice: October

2005, Vol 54, Number 10.

7. Goldberg, L. and Dimeff, R. Sideline Management of Sports-related Concussions. Sports Medicine and Arthroscopy

Review: Vol 14 (4), December 2006, pp 199-205.

8. Kushner, D. Concussion in Sports: Minimizing the Risk for Complications. American Family Physician: Vol 64, Number 6,

pp 1007-1014.

9. Tator, C. Concussions are Brain Injuries and Should be Taken Seriously. Can. J. Neurol. Sci. 2009: Vol 36, pp 269-270.

10. Mayers, L. Return-to-Play Criteria After Athletic Concussion. Arch. Neurology 2008: Vol 65, Number 9, pp 1158-1161.

11. Covassin, T. and Elbin, R. Current Sport-Related Concussion Teaching and Clinical Practices of Sports Medicine

Professionals. Journal of Athletic Training: Vol 44, Number 4, August 2009, pp 400-404.

12. Davis, G.A. and Iverson, G.L. Contributions of Neuroimaging, Balance Testing, Electrophysiology, and Blood Markers to

the Assessment of Sport-related Concussion. Br. J. Sports Med 2009: Vol 43 (Suppl I), i36-i45.

References

13. Johnston, K. and Ptito, A. New Frontiers in Diagnostic Imaging in Concussive Head Injury. Clin. J. Sport Med: Vol 11,

Number 3, 2001, pp 166-175.

14. Schrader, H. and Mickeviciene, D. Magnetic resonance imaging after most common form of concussion. BMC

Medical Imaging 2009: Vol 9, Number 11, pp 1-6.

15. Iverson, G. Outcome from mild traumatic brain injury. Current Opinion in Psychiatry 2005: Vol 18, pp 301-317.

16. Paoli de Almeida Lima, D. and Simao Filho, C. Quality of life and neuropsychological changes in mild head trauma.

Late analysis and correlation with S100B protein and cranial CT scan performed at hospital admission. Injury, Int. J.

Care Injured 2008: Vol 39, pp 604-611.

17. Kristman, V. and Tator, C. Does the Apolipoprotein E4 Allele Predispose Varsity Athletes to Concussion? A

Prospective Cohort Study. Clin. J. Sport Med: Vol 18, Number 4, July 2008, pp 322-328.

18. Roland Terrell, T. and Bostick, R. APOE, APOE Promoter, and Tau Genotypes and Risk for Concussion in College

Athletes. Clin. J. Sport Med: Vol 18, Number 1, January 2008, pp 10-17.

19. Hutchinson, M. and Mainwaring, L. Differential Emotional Responses of Varsity Athletes to Concussion and

Musculoskeletal Injuries. Clin. J. Sport Med: Vol 19, Number 1, January 2009, pp 13-19.

20. Bruce, J. and Echemendia, R. History of Multiple Self-reported Concussions is Not Associated with Reduced

Cognitive Abilities. Neurosurgery: Vol 64, Number 1, January 2009, pp 100-105.

21. The ImPACT Test. Sideline ImPACT. http://www.impacttest.com/sidelineimpact.php.

22. Schatz, P. and Pardini, J. Sensitivity and specificity of the ImPACT Test Battery for concussion in athletes. Archives of

Clin. Neuropsychology: Vol 21, Issue 1, January 2006, pp 91-99.

23. Cernich, A. and Reeves, D. Automated Neuropsychological Assessment Metrics Sports Medicine Battery. Archives of

Clin. Neuropsychology: 22S (2007) S101-114.

24. Broglio, S and Macciochi, S. Sensitivity of the Concussion Assessment Battery. Neurosurgery: Vol 60, Number 6,

June 2007, pp 1050-1058.

References

25. McCrea, M. and Barr, W. Standard regression-based methods for measuring recovery after sport-related concussion.

Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society (2005): Vol 11, pp 58-69

26. Shuttleworth-Edwards, A. Central or peripheral? A positional stance in reaction to the Prague statement on the role of

neuropsychological assessment in sports concussion management. Archives of Clin. Neuropsychology 2008: Vol 23, pp

479-485.

27. Guskiewicz, K. Postural Stability Assessment Following Concussion: One Piece of the Puzzle. Clin. J. Sport Med

2001: Vol 11, pp 182-189.

28. Solomon, G. and Haase, R. Biopsychosocial characterisitics and neurocognitive test performance in National Football

League players: An initial assessment. Arch. of Clin. Neuropsych 2008: Vol 23, pp 563-577.

29. Boutin, D. and Lassonde, M. Neuropsychological assessment prior to and following sports-related concussion during

childhood: A case study. Neurocase 2008: Vol 14, Number 3, pp 239-248.

30. Scolaro Moser, R. and Iverson, G. Neuropsychological evaluation in the diagnosis and management of sports-related

concussion. Arch of Clin. Neuropsych: Vol 22, Issue 8, November 2007, pp 909-916.

31. Maroon, J. and Lovell, M. Cerebral Concussion in Athletes: Evaluation and Neuropsychological Testing. Neurosurgery: Vol 47,

Number 3, September 2000, pp 659-672.

32. Grindel, S. and Lovell, M. The Assessment of Sport-Related Concussion: The Evidence Behind Neuropsychological

Testing and Management. Clin. J. of Sport Med 2001: Vol 11, pp 134-143.

33. Broglio, S. and Macciochi, S. Neurocognitive Performance of Concussed Athletes When Symptoms Free. Journal of

Athletic Training 2007: Vol 42, Number 4, pp 504-508.

34. Echemendia, R. and Herring, S. Who should conduct and interpret the neuropsychological assessment in sports-

related concussion? Br. J. Sports Med 2009: 43 (Suppl I) pp i32-i35.

35. Putukian, M. and Aubry, M. Return to play after sports concussion in elite and non-elite athletes. Br. J. Sports Med

2009: 43 (Suppl I) pp i28-i31.

36. Cohen, J. and Giola, G. Sports-related concussion in pediatrics. Current Opinion in Pediatrics 2009: Vol 21, pp 288-293.

37. De Beaumont, L. and Theoret, H. Brain function decline in healthy retired athletes who sustained their last sports concussi on in

early adulthood. Brain 2009: Vol 132, pp 695-708.

References

38. Covassin, T. and Swanik, C. B. Sex differences in baseline neuropsychological function and concussion symptoms of

collegiate athletes. Br. J. Sports Med 2006: Vol 40, pp 923-927.

39. Covassin, T. and Schatz, P. Sex differences in neuropsychological function and post-concussion symptoms of

concussed collegiate athletes. Neurosurgery 2007: Vol 61, pp 345-351.

40. Standaert, C. and Herring, S. Expert Opinion and Controversies in Sports and Musculoskeletal Medicine: Concussion

in the Young Athlete. Arch Phys Med Rehabil: Vol 88, pp 1077-1079, August 2007.

41. Scolaro Moser, R. and Schatz, P. Enduring effects of concussion in youth athletes. Arch of Clin. Neuropsych 2001:

Vol 17, Issue 1, January 2002, pp 91-100.

42. Field, M. and Collins, M. Does age play a role in recovery from sports-related concussion? A comparison of high

school and collegiate athletes. Journal of Pediatrics: Vol 42, Issue 5, May 2003.

43. Kirkwood, M. and Owen Yeates, K. Pediatric Sport-Related Concussion: A Review of the Clinical Management of an

Oft-Neglected Population. Pediatrics: Vol 117, Number 4, April 2006, pp 1359-1371.

44. Ashare, A. Returning to play after concussion. Acta Paediatrica 2009: Vol 98, pp 774-776.

45. Purcell, L. What are the most appropriate return-to-play guidelines for concussed child athletes? Br. J. Sports Med

2009: Vol 43 (Suppl I) pp i51-i55.

46. Gessel, L. and Fields, S. Concussions Among United States High School and Collegiate Athletes. Journal of Athletic

Training: Vol 42, Number 4, December 2007, pp 495-503.

47. Giola, G. A. and Schneider, J. C. Which symptom assessments and approaches are uniquely appropriate for

paediatric concussion? Br. J. Sports Med 2009: Vol 43 (Suppl I), pp i13-i22.

48. Dick, R. W. Is there a gender difference in concussion incidence and outcomes? Br. J. Sports Med 2009: Vol 43

(Suppl I), pp i46-i50.

49. McCrory, P. Does Second Impact Syndrome Exist? Clin. J. Sport Med 2001: Vol 11, Number 3, pp 144-149.

50. Guskiewicz, K. and McCrea, M. Cumulative Effects Associated With Recurrent Concussion in Collegiate Football

Players. JAMA: Vol 290, Number 19, November 19, 2003, pp 2549-2555.

References

51. McCrea, M. and Guskiewicz, K. Acute Effects and Recovery Time Following Concussion in Collegiate Football

Players. JAMA: Vol 290, Number 19, November 19, 2003, pp 2556-2563.

52. Covassin, T. and Stearne, D. Concussion History and Postconcussion Neurocognitive Performance and Symptoms in

Collegiate Athletes. Journal of Athletic Training 2008: Vol 43, Number 2, pp 119-124.

53. Miller, G. A Late Hit for Pro Football Players. Science: Vol 325, August 7, 2009, pp 670-672.

54. Singh, G. D. and Maher, G. Customized mandibular orthotics in the prevention of concussion/mild traumatic brain

injury in football players: a preliminary study. Dental Traumatology: Vol 25, Issue 5, July 9, 2009, pp 515-521.

55. Levy, M. and Ozgur, B. Birth and Evolution of the Football Helmet. Neurosurgery: Vol 55, Number 3, September 2004,

pp 656-662.

56. Levy, M. and Ozgur, B. Analysis and Evolution of Head Injury in Football. Neurosurgery: Vol 55, Number 3,

September 2004, pp 649-655.

57. Benson, B. W. and Hamilton, G. M. Is protective equipment useful in preventing concussion? A systematic review of

the literature. Brit. J. Sport Med 2009: Vol 43 (Suppl I), pp i56-i67.

You might also like

- Hirschsprung’s Disease, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsFrom EverandHirschsprung’s Disease, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsNo ratings yet

- Gastric Outlet Obstruction, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsFrom EverandGastric Outlet Obstruction, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsNo ratings yet

- Nurs 641 Case Study PresentationDocument12 pagesNurs 641 Case Study Presentationapi-251235373No ratings yet

- Research DesignDocument4 pagesResearch DesignAbdul BasitNo ratings yet

- NCPDocument16 pagesNCPmmlktiNo ratings yet

- Copar RubricsDocument3 pagesCopar RubricsirisaivirtudezNo ratings yet

- NPI Reflects Spring 2013Document12 pagesNPI Reflects Spring 2013npinashvilleNo ratings yet

- Pleural EffusionDocument2 pagesPleural EffusionGellie Santos100% (1)

- Overcoming Social Phobia Through CBT and HypnosisDocument3 pagesOvercoming Social Phobia Through CBT and HypnosisFaRaz MemOnNo ratings yet

- Assess Patients HolisticallyDocument18 pagesAssess Patients HolisticallySavita Hanamsagar100% (1)

- Chapter 3 Client PresentationDocument4 pagesChapter 3 Client PresentationEllePeiNo ratings yet

- Spinal Cord Injury: Andi IhwanDocument31 pagesSpinal Cord Injury: Andi IhwanAndi Muliana SultaniNo ratings yet

- PHC (Nursing Negligence Case)Document2 pagesPHC (Nursing Negligence Case)Gena RealNo ratings yet

- Process Recording 360Document9 pagesProcess Recording 360MarvinNo ratings yet

- Brief Description of The Disease/statistical IncidenceDocument2 pagesBrief Description of The Disease/statistical IncidenceLeanne Princess Gamboa100% (1)

- Quality Control in Endoscopy Unit: Safety Considerations For The PatientDocument13 pagesQuality Control in Endoscopy Unit: Safety Considerations For The PatientPamela PampamNo ratings yet

- Pat 2 Medsurg1Document20 pagesPat 2 Medsurg1api-300849832No ratings yet

- DDH Treatment - PFDocument30 pagesDDH Treatment - PFHendra SantosoNo ratings yet

- Cultural Competence in NursingDocument6 pagesCultural Competence in NursingAmiLia CandrasariNo ratings yet

- Patient ChartDocument2 pagesPatient ChartHydieNo ratings yet

- Nursing Care Plan For Subarachnoid HemorrhagicDocument2 pagesNursing Care Plan For Subarachnoid HemorrhagicAshram Smart100% (1)

- Reflective ExemplarDocument2 pagesReflective Exemplarapi-531834240No ratings yet

- Nursing Reflection - 1st Year PostingDocument5 pagesNursing Reflection - 1st Year PostingNurul NatrahNo ratings yet

- Nursing Care of Stroke - NewDocument4 pagesNursing Care of Stroke - Newninda saputriNo ratings yet

- Nursing Care Plan: Ineffective CopingDocument2 pagesNursing Care Plan: Ineffective CopingRosalinda SalvadorNo ratings yet

- CasestudyutiDocument21 pagesCasestudyutidael_05No ratings yet

- Acute Appendicitis PowerpointDocument34 pagesAcute Appendicitis PowerpointJaysonPangilinanAban100% (1)

- 2 Critical Care UnitDocument59 pages2 Critical Care UnitPALMA , JULIA A.No ratings yet

- Jake Yvan Dizon Case Study, Chapter 49, Assessment and Management of Patients With Hepatic DisordersDocument8 pagesJake Yvan Dizon Case Study, Chapter 49, Assessment and Management of Patients With Hepatic DisordersJake Yvan DizonNo ratings yet

- Cardiac NSG DiagnosisDocument5 pagesCardiac NSG DiagnosisShreyas WalvekarNo ratings yet

- Key Steps of Evidence-Based Practice: What Type of Question Are You Asking and What Will The Evidence Support?Document29 pagesKey Steps of Evidence-Based Practice: What Type of Question Are You Asking and What Will The Evidence Support?Ron OpulenciaNo ratings yet

- Typhoid FeverDocument38 pagesTyphoid FeverRonelenePurisimaNo ratings yet

- Hiatal HerniaDocument3 pagesHiatal HerniaJobelle AcenaNo ratings yet

- Cervical Conization and The Risk of Preterm DeliveryDocument11 pagesCervical Conization and The Risk of Preterm DeliveryGelo ConcepcionNo ratings yet

- MSEDocument20 pagesMSEJenny YenNo ratings yet

- PCAP-C Endorsement NotesDocument2 pagesPCAP-C Endorsement NotesLorraine GambitoNo ratings yet

- Final Thesis With CV (For Bookbind)Document138 pagesFinal Thesis With CV (For Bookbind)Bea Marie Eclevia100% (1)

- Head NursingDocument8 pagesHead NursingShannie PadillaNo ratings yet

- Mental Health Nursing Case Study - CompleteDocument12 pagesMental Health Nursing Case Study - Completeapi-546486919No ratings yet

- N375 Critical Thinking Activity ExampleDocument6 pagesN375 Critical Thinking Activity ExamplefaizaNo ratings yet

- Mental Health Continuum ExplainedDocument2 pagesMental Health Continuum ExplainedAileen A. MonaresNo ratings yet

- Cva Case PDFDocument39 pagesCva Case PDFEmsy Ni ThelayNo ratings yet

- Running Head: A Patient Who Has Glaucoma 1Document10 pagesRunning Head: A Patient Who Has Glaucoma 1Alonso LugoNo ratings yet

- Rebira 1Document36 pagesRebira 1Rebira WorkinehNo ratings yet

- Carotid Endarterectomy: Medical and Surgical NursingDocument17 pagesCarotid Endarterectomy: Medical and Surgical NursingMonette Abalos MendovaNo ratings yet

- Dengue ArticleDocument16 pagesDengue ArticleJobelAringoNuvalNo ratings yet

- Spinal Cord Injury Case Study (Physical Assessment)Document3 pagesSpinal Cord Injury Case Study (Physical Assessment)TobiDaNo ratings yet

- Asthma CWUDocument8 pagesAsthma CWUNabilah ZulkiflyNo ratings yet

- Case Study 2 AlsDocument24 pagesCase Study 2 Alsapi-347153077No ratings yet

- Demo Teaching Physical Health AssessmentDocument5 pagesDemo Teaching Physical Health AssessmentJulie May SuganobNo ratings yet

- Electrolyte ImbalanceDocument4 pagesElectrolyte ImbalanceDoneva Lyn MedinaNo ratings yet

- Cerebrovascular AccidentDocument62 pagesCerebrovascular AccidentJaydee DalayNo ratings yet

- Psych - Chapter 23 Into To Milieu ManagementDocument4 pagesPsych - Chapter 23 Into To Milieu ManagementKaren かれんNo ratings yet

- MseDocument5 pagesMseYnaffit Alteza UntalNo ratings yet

- Case Report GBSDocument31 pagesCase Report GBSAde MayashitaNo ratings yet

- Brain TumorDocument50 pagesBrain TumorbudiNo ratings yet

- Nursing Interview Guide To Collect Subjective Data From The Client Questions RationaleDocument19 pagesNursing Interview Guide To Collect Subjective Data From The Client Questions RationaleKent Rebong100% (1)

- Dengue FeverDocument5 pagesDengue FeverMae AzoresNo ratings yet

- Meniere's Disease.Document30 pagesMeniere's Disease.June Yasa HacheroNo ratings yet

- Mehreen Khan: BS (UET, Lahore) MS (NUST, Islamabad) Mehreen - Khan@cust - Edu.pkDocument34 pagesMehreen Khan: BS (UET, Lahore) MS (NUST, Islamabad) Mehreen - Khan@cust - Edu.pkPřîñçè Abdullah SohailNo ratings yet

- Classification of ComaDocument14 pagesClassification of ComaCiiFitriNo ratings yet

- Concussion: University of Pittsburgh's Brain Trauma Research CenterDocument14 pagesConcussion: University of Pittsburgh's Brain Trauma Research CenterCiiFitriNo ratings yet

- Assessment of Concussion from Sideline to ClinicDocument36 pagesAssessment of Concussion from Sideline to ClinicCiiFitriNo ratings yet

- Classification of ComaDocument14 pagesClassification of ComaCiiFitriNo ratings yet

- CONCUSSION CARE: SIMPLE STEPSDocument17 pagesCONCUSSION CARE: SIMPLE STEPSCiiFitriNo ratings yet

- Concussion: University of Pittsburgh's Brain Trauma Research CenterDocument14 pagesConcussion: University of Pittsburgh's Brain Trauma Research CenterCiiFitriNo ratings yet

- Coma: Detecting Signs of Consciousness in Severely Brain Injured Patients Recovering From ComaDocument29 pagesComa: Detecting Signs of Consciousness in Severely Brain Injured Patients Recovering From ComaCiiFitriNo ratings yet

- Grief Work BlatnerDocument7 pagesGrief Work Blatnerbunnie02100% (1)

- Annexure 'CD - 01' FORMAT FOR COURSE CURRICULUMDocument4 pagesAnnexure 'CD - 01' FORMAT FOR COURSE CURRICULUMYash TiwariNo ratings yet

- AutohalerDocument51 pagesAutohalerLinto JohnNo ratings yet

- 37 Percent Formaldehyde Aqueous Solution Mixture of Hcho Ch3oh and H2o Sds p6224Document12 pages37 Percent Formaldehyde Aqueous Solution Mixture of Hcho Ch3oh and H2o Sds p6224Juan Esteban LopezNo ratings yet

- Crabtales 061Document20 pagesCrabtales 061Crab TalesNo ratings yet

- The Privileges and Duties of Registered Medical Practitioners - PDF 27777748Document6 pagesThe Privileges and Duties of Registered Medical Practitioners - PDF 27777748innyNo ratings yet

- House-Tree-Person Projective Technique A Validation of Its Use in Occupational TherapyDocument11 pagesHouse-Tree-Person Projective Technique A Validation of Its Use in Occupational Therapyrspecu100% (1)

- NCP Infection NewDocument3 pagesNCP Infection NewXerxes DejitoNo ratings yet

- 110 TOP SURGERY Multiple Choice Questions and Answers PDF - Medical Multiple Choice Questions PDFDocument11 pages110 TOP SURGERY Multiple Choice Questions and Answers PDF - Medical Multiple Choice Questions PDFaziz0% (1)

- Closing The Gap 2012Document127 pagesClosing The Gap 2012ABC News OnlineNo ratings yet

- Fphar 12 768268Document25 pagesFphar 12 768268Araceli Anaya AlvaradoNo ratings yet

- Beggs Stage 1 - Ortho / Orthodontic Courses by Indian Dental AcademyDocument33 pagesBeggs Stage 1 - Ortho / Orthodontic Courses by Indian Dental Academyindian dental academyNo ratings yet

- Surgical Treatment For BREAST CANCERDocument5 pagesSurgical Treatment For BREAST CANCERJericho James TopacioNo ratings yet

- Sinclair ch05 089-110Document22 pagesSinclair ch05 089-110Shyamol BoseNo ratings yet

- Toxicology Procedures ManualDocument227 pagesToxicology Procedures ManualBenjel AndayaNo ratings yet

- Sickle Cell Diet and NutritionDocument30 pagesSickle Cell Diet and NutritiondaliejNo ratings yet

- Overcoming Low Self-Esteem Extract PDFDocument40 pagesOvercoming Low Self-Esteem Extract PDFMarketing Research0% (1)

- R3 Vital Pulp Therapy With New MaterialsDocument7 pagesR3 Vital Pulp Therapy With New MaterialsWening TyasNo ratings yet

- Antipsychotic Agents: Conventional vs AtypicalDocument18 pagesAntipsychotic Agents: Conventional vs AtypicalmengakuNo ratings yet

- Drug StudyDocument17 pagesDrug StudyJoan RabeNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1Document15 pagesChapter 1ErikaNo ratings yet

- MidazolamDocument18 pagesMidazolamHarnugrahanto AankNo ratings yet

- Vivid I and Vivid Q Cardiovascular Ultrasound: SectorDocument4 pagesVivid I and Vivid Q Cardiovascular Ultrasound: SectorShaikh Emran HossainNo ratings yet

- High Level Technical Meeting On Health Risks at The Human-Animal-Ecosystems Interfaces Mexico City, Mexico 15-17 November 2011Document7 pagesHigh Level Technical Meeting On Health Risks at The Human-Animal-Ecosystems Interfaces Mexico City, Mexico 15-17 November 2011d3bd33pNo ratings yet

- Vidas Troponin High Sensitive Ref#415386Document1 pageVidas Troponin High Sensitive Ref#415386Mike GesmundoNo ratings yet

- 5105 - Achilles TendonDocument30 pages5105 - Achilles Tendonalbertina tebayNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0022391302002998 MainDocument5 pages1 s2.0 S0022391302002998 MainManjeev GuragainNo ratings yet

- Anderson2008 Levofloxasin A ReviewDocument31 pagesAnderson2008 Levofloxasin A ReviewFazdrah AssyuaraNo ratings yet

- CPV/CCV Ag (3 Lines) : VcheckDocument2 pagesCPV/CCV Ag (3 Lines) : VcheckFoamfab WattikaNo ratings yet

- Denumire Comerciala DCI Forma Farmaceutica ConcentratieDocument4 pagesDenumire Comerciala DCI Forma Farmaceutica ConcentratieAlina CiugureanuNo ratings yet